Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

B-1816, the aircraft involved in the accident, seen here in 1993 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 26 April 1994 |

| Summary | Stalled and crashed while landing |

| Site | Nagoya Airport, Nagoya, Japan 35°14′43″N 136°55′56″E / 35.2453°N 136.9323°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A300B4-622R |

| Operator | China Airlines |

| IATA flight No. | CI140 |

| ICAO flight No. | CAL140 |

| Call sign | DYNASTY 140 |

| Registration | B-1816 |

| Flight origin | Chiang Kai-Shek International Airport, Taiwan |

| Destination | Nagoya Airport |

| Occupants | 271 |

| Passengers | 256 |

| Crew | 15 |

| Fatalities | 264 |

| Injuries | 7 |

| Survivors | 7 |

China Airlines Flight 140 was a regularly scheduled passenger flight from Chiang Kai-shek International Airport (serving Taipei, Taiwan) to Nagoya Airport in Nagoya, Japan.[note 1]

On 26 April 1994, the Airbus A300 serving the route was completing a routine flight and approach, when, just seconds before landing at Nagoya Airport, the takeoff/go-around setting (TO/GA) was inadvertently triggered. The pilots attempted to pitch the aircraft down while the autopilot, which was not disabled, was pitching the aircraft up. The aircraft ultimately stalled and crashed into the ground, killing 264 of the 271 persons on board. The event remains the deadliest accident in the history of China Airlines, the second deadliest air crash in Japanese history after Japan Air Lines Flight 123, and the third deadliest air crash involving the Airbus A300.[1][2][3]

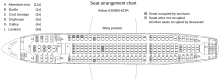

The aircraft involved was an Airbus A300B4-622R, registered as B-1816, manufacturer serial number 580. It was manufactured by Airbus Industrie on 29 January 1991 and was delivered to China Airlines on 2 February. It had logged 8572 hours and 12 minutes of airframe hours with 3910 takeoff and landing cycles. It was also equipped with two Pratt & Whitney PW4158 engines.[4][5]

The flight took off from Chiang Kai-shek International Airport at 16:53 Taiwan Standard Time bound for Nagoya Airport. At the controls were Captain Wang Lo-chi (Chinese: 王樂琦; pinyin: Wáng Lèqí), age 42, and First Officer Chuang Meng-jung (莊孟容; Zhuāng Mèngróng), age 26.[note 2][6]: 13–14 [7][8] The en-route flight was uneventful; the descent started at 19:47 and the aircraft passed the outer marker at 20:12. Just 3 nautical miles (3.5 mi; 5.6 km) from the runway threshold at 1,000 feet (300 m) above ground level (AGL), the first officer (co-pilot) inadvertently selected the takeoff/go-around setting (also known as a TO/GA), which tells the autopilot to increase the throttles to take off/go-around power.[9][6]

The crew attempted to correct the situation, manually reducing the throttles and pushing the yoke forward. However, they did not disconnect the autopilot, which was still acting on the inadvertent go-around command it had been given, so it increased its own efforts to overcome the action of the pilot. The autopilot followed its procedures and moved the horizontal stabilizer to its full nose-up position. The pilots, realizing the landing must be aborted and not realizing that the TO/GA was still engaged, then knowingly executed a manual go-around, pulling back on the yoke and adding to the nose-up attitude that the autopilot was already trying to execute. The aircraft levelled off for about 15 seconds and continued descending until about 500 feet (150 m) where there were two bursts of thrust applied in quick succession and the aircraft was nose up in a steep climb. The resulting extreme nose-up attitude, combined with decreasing relative airspeed due to insufficient thrust, resulted in an aerodynamic stall. Airspeed dropped quickly, the aircraft stalled and struck the ground at 20:15:45.[9] 31-year-old Noriyasu Shirai, a survivor, said that a flight attendant announced that the aircraft would crash after it stalled.[10] Sylvanie Detonio, the only survivor who could be interviewed on 27 April, said that passengers received no warning prior to the crash.[11]

Of the 271 people on board (15 crew and 256 passengers), seven passengers survived. All of the survivors were seated in rows 7 through 15. On 27 April 1994, officials said there were 10 survivors (including a three-year-old) and that a Filipino, two Taiwanese, and seven Japanese survived.[11] By 6 May, only seven remained alive, including three children.[10]

The passengers included 153 Japanese citizens[11] and 18 Filipino citizens.[12] Taiwanese citizens made up a large portion of the remainder.[11]

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | 63[citation needed] | 14 | 77 |

| Japan | 153 | 1 | 154 |

| Philippines | 18 | 0 | 18 |

| China | 39[citation needed] | 0 | 39[citation needed] |

| Total | 256 | 15 | 271 |

The crash, which destroyed the aircraft (delivered less than three years earlier in 1991), was primarily attributed to crew error for their failure to correct the controls as well as the airspeed.[9] An update which would disengage the GO-AROUND autopilot if certain controls were moved[13], which would have included the yoke-forward movement the pilots made on the fatal flight, wasn't deemed urgent enough by Air China for a non-routine trip to the hangar for maintenance to install the update.[13] These factors were deemed contributing incidents to the crash, after the primary failure of the pilots to take control of the situation once it began.[9]

The investigation also revealed that the pilot had been trained for the A300 on a flight simulator in Bangkok which was not programmed with the problematic GO-AROUND behavior. Therefore, his belief that pushing on the yoke would override the automatic controls was appropriate for the configuration he had trained on, as well as for the Boeing 747 aircraft that he had spent most of his career flying.[14]

Japanese prosecutors declined to pursue charges of professional negligence on the airline's senior management as it was "difficult to call into question the criminal responsibility of the four individuals because aptitude levels achieved through training at the carrier were similar to those at other airlines". The pilots could not be prosecuted since they had died in the accident.[15]

A class action suit was filed against China Airlines and Airbus Industries for compensation. In December 2003, the Nagoya District Court ordered China Airlines to pay a combined 5 billion yen to 232 people, but cleared Airbus of liability. Some of the bereaved and survivors felt that the compensation was inadequate and a further class action suit was filed and ultimately settled in April 2007 when the airline apologized for the accident and provided additional compensation.[16]

There had been earlier "out-of-trim incidents" with the Airbus A300-600R.[13] Airbus had the company that made the flight control computer produce a modification to the air flight system that would disengage the autopilot "when certain manual controls input is applied on the control wheel in GO-AROUND mode [13] This modification was first available in September 1993 and the aircraft that had crashed had been scheduled to receive the upgrade.[13] The aircraft had not received the update at the time of the crash because "China Airlines judged that the modifications were not urgent".[13]

On 3 May 1994, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) of the Republic of China (Taiwan) ordered China Airlines to modify the flight control computers following Airbus's notice of the modification.[13] On 7 May 1994, the CAA ordered China Airlines to provide supplementary training and a re-evaluation of proficiency to all A300-600R pilots.[13]

Following the crash, China Airlines decided to retire flight number CI140 and instead designate the Taipei-Nagoya service to CI150.[17] As of May 2024, China Airlines still operate this service, operating in and out of Chubu Centrair International Airport after it opened in 2005, moving from Komaki Airport. Today, Komaki serves limited domestic flights as well as military and other non-commercial aviation.

On 26 April 2014, 300 mourners gathered in Kasugai, Aichi Prefecture, for a memorial ceremony on the 20th anniversary of the crash.[18] Another memorial service was held there on 26 April 2024, the 30th anniversary.[19]

The crash was featured in the ninth episode of season 18 of Mayday (Air Crash Investigation). The episode is titled "Deadly Go-Round".[14]