Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Burlington railroad strike of 1888 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Strikers attacking strikebreaking switchmen and brakemen near the stockyards in Chicago. | |||

| Date | February 27 – December, 1888 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | Wage increase | ||

| Methods | Striking, sabotage | ||

| Resulted in | Strikers laid off | ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

Peter M. Arthur, Henry B. Stone, | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

The Burlington railroad strike of 1888 was a failed union strike which pitted the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (B of LE), the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (B of LF), and the Switchmen's Mutual Aid Association (SMAA) against the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) its extensive trackage in the Midwestern United States. It was led by the skilled engineers and firemen, who demanded higher wages, seniority rights, and grievance procedures. It was fought bitterly by management, which rejected the very notion of collective bargaining. There was much less violence than the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, but after 10 months the very expensive company operation to permanently replace all the strikers was successful and the strike was a total defeat for them.[1]

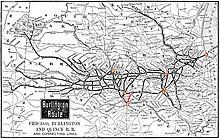

The Burlington system of railroads was one of the great transportation networks of the 19th Century, operating about 6,000 miles of line in 1888, the year of the great strike.[2] The system consisted of seven individual railroads, of which the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) was the core unit, headed by company President Charles Elliott Perkins from 1881 and young General Manager Henry B. Stone.[3] The line was conservatively managed and profitable, paying its largely Boston-based[4] investors healthy annual dividends of 8 percent throughout the decade of the 1880s.[2]

The profitability of the Burlington line rested on the twin pillars of maintenance of high shipping rates through pricing agreements with competitive lines[5] and the suppression of wage rates, with President Perkins taking the view that wages were set by the simple market principle of supply and demand, leaving no room for misguided external intervention practices such as arbitration.[6]

Perkins was hostile to the notion of unionization and to the strike movement, approving a local decision to terminate striking Chicago freight handlers in 1886 and seeking to "go for" the Knights of Labor (KOL) in the wake of that union's strikes upon other rail lines in that year.[7] The company formally served notice on its workers that membership in the KOL and continued employment by the Burlington line was incompatible, forcing many members to quit the union to keep their jobs.[7]

During the era of steam locomotion, operation of an engine was a two-person job, with an engineer controlling the throttle and responsible for the vehicle's safe operation, alongside a lesser-paid fireman, who broke coal into combustible-sized pieces and stoked the boiler which provided the train's motive energy.[8] These two cab-dwelling operators were together known as "enginemen," with the typically young fireman subordinate to the engineer and generally an aspirant to later promotion to the rank of engineer.[9] Despite their proximity in the workplace and their commonality of interests, these two groups maintained their own distinct craft organizations, which frequently stood a cross-purposes with one another, divided by jurisdictional jealousy.

Membership in these craft brotherhoods, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (B of LE) and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (B of LF), which were historically fraternal benefit-societies and which had taken a bleak view of the efficacy of striking, was still tolerated.[10] These seem to have represented little risk to the company, with the B of LE having engaged in no strikes anywhere since its various local defeats in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877,[11] and the firemen a seemingly easily replaceable group of lesser skilled workers with a similar tradition of antipathy to strikes and collaboration with employers.[12]

On January 23, 1888, a meeting of the grievance committee of the B of LE was convened at Burlington, Iowa, joined by the adjusting committee of the B of LF.[13] the two bodies met individually for two days to identify their own specific concerns before holding a joint session on January 25, at which a negotiating committee of 14 engineers and 14 firemen was elected.[13] The cause of an engineer terminated the previous week by the CB&Q, ostensibly for failing to maintain a schedule, which the B of LE believed was mitigated by a defective watch, was placed near the top of the joint committee's agenda.[14] Adding fuel to the fire was the terminated engineer's important place in the B of LE as a member of the brotherhood's previous grievance committee.[15]

A meeting of the joint grievance committee with General Manager Stone over the fate of the fired engineer was sought without success, and he left to Burlington to take a new position with the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad in short order.[16] Bad will remained in the aftermath.

The fate of the fired engineer was not the primary cause of the strike. A further and far more intractable division between the employees and the railroad related to a new schedule of pay for enginemen put forward on February 15 by the grievance committee, which sought to eliminate a much maligned system of differential pay based upon the time employees had spent with the company and specific conditions of various routes, and instead basing pay upon raw mileage traveled — a method of wage calculation which would have had the effect of significantly increasing wages across the board.[17]

The profitable Burlington system and its method of pay according to a myriad of classifications was seen by employees as significantly less remunerative than the pay scales in use by other railroads in the Chicago area, which tended to be based upon mileage traveled. The summary rejection of the change to a mileage-based system by the unyielding General Manager Stone via a circular letter dated February 22, reaffirmed in a series of face-to-face negotiations over subsequent days, set the stage for a work stoppage.[18]

The nature of the pay increase was frankly admitted. In a contemporary history of the strike, B of LE official John A. Hall acknowledged that

"It is true that the Brotherhoods have demanded ... 'a considerable average increase of pay,' but the public must understand that they did not demand this increase from the Burlington over what is paid by its competitors in business. Had the Burlington conceded this increase of pay, it would only have been called upon to pay precisely what its neighbors and rivals have been paying for years. A large average increase of pay must be made before the employees of this road are placed upon an equal footing with those of other roads. For many years the Burlington road had the advantage of a first-class equipment of enginemen at rates of pay far below what its competitors have been compelled to pay for the same service."[19]

In an effort to break the impasse head of the B of LE Peter M. Arthur and head of the B of LF Frank P. Sargent were brought into Chicago on the morning of February 23.[20] In discussions with General Manager Stone, Arthur noted that 90 percent of neighboring roads paid their enginemen by the mile; an offer was made to accept a lower rate of mileage pay — 3.5 cents per mile for engineers running passenger lines rather than the 4 cents per mile previously demanded.[20] Stone refused to move from the current pay schedule and rates on behalf of the railroad, effectively ending the initiative.[20]

The brotherhood chiefs sent a telegram to President Perkins declaring their men to be "determined to strike" but "we want to prevent it" and offering to accept the "same terms as made with the Chicago and Alton Railroad and Santa Fe system — that is, 3.5 cents per mile for passenger trains and 4 cents per mile for the slower freight trains for engineers, with firemen receiving 60 percent of these rates.[21] Perkins responded that while "the CB&Q is ready and expects to pay as good wages as are paid by its neighbors," at the same time "the railroad situation is not such as to justify any general increase at present" and indicating plans to arrive in Chicago in about a week's time.[22]

This vague offer proved unsatisfactory, however, and the joint committee of engineers and firemen, in consultation with the brotherhood heads, voted to strike for the new methods and rates of pay.[23] The strike was slated to begin early in the morning of Monday, February 27, and the various delegates of the grievance committee departed for their respective homes along the Burlington line to announce the decision in person and make preparations for a strike.[23] No announcement was to be made to the company until noon on February 26, in the hopes that a last-minute settlement might be arranged or alternatively company preparations for the stoppage be left wanting.[24]

At the appointed time of 4 am on February 27, engineers and firemen across the CB&Q Railroad abandoned their engines at their terminal points, halting their routes and returning to the nearest terminal point if they were already on the road.[25] The company, having been formally notified of the strike date only the day before and believing that more time remained for negotiations, was taken by surprise.[26] Company officials in Chicago immediately determined that their top priority was to keep suburban commuter trains running if possible, with the line standing as the second largest suburban commuter line in the region.[27] No freight traffic would be run until passenger service was restored, company officials determined.[27]

The loss of CB&Q freight service was particularly damaging to the massive Chicago meatpacking industry, with the road the number one importer of live cattle into the city for slaughter.[27] The line also was positioned to have a dominant transportation role for the city's lumber industry, which would be quickly submerged by filled railroad cars unable to reach other lines save over gridlocked Burlington tracks.[28]

Emergency crews consisting of an engineer and fireman had been chosen to run passenger trains on the morning of February 27 if regular crews failed to show up for work at the appointed hour.[29] Company officials expected that about 40 percent of regular crew members would remain on the job despite the strike; brotherhood officials predicted a total walkout.[30] Ultimately union officials were more correct, with only 22 engineers out of 1,052 and 23 firemen out of 1,085 remaining on the job after the strike deadline, barely 2% of the company's enginemen.[30]

Strikers anticipated that the railroad could not function without them and anticipated a speedy settlement on favorable monetary terms, with some of them leaving personal belongings in the roundhouses after the strike deadline.[31] In this they greatly miscalculated.

During the first three days of the strike company employees were called in from around the region to don overalls and operate passenger engines.[32] These included the Superintendent of the CB&Q's Iowa lines, the superintendents of the telegraph and water service, 14 of the line's conductors, and several brakemen.[32] Sundry employees were used as temporary firemen, running the gamut from mechanics to an assistant superintendent.[32] Only four new engineers hired as strikebreakers were sent out on the road during this period.[32]

Hiring of replacement workers — contemptuously known as "scabs" by striking workers — began apace, with the emergency conscripts from the ranks of management returned to their jobs as rapidly as the quantity of new hires allowed.[32]

Perkins brought in strikebreakers and Pinkerton agents.[33] On March 5, the union asked unionized workers on other railroads to boycott the CB&Q by refusing to load freight onto its trains; Perkins went to federal court on March 8,[34] to seek an injunction that would require the other railroads to load freight onto the CB&Q. The federal court issued the injunction on March 13, and almost every aspect of labor relations on every railroad engaged in interstate commerce came under court control.

The strike was effectively broken within a month, but it lingered in some western states for another 10 months.

Several workers were killed in violent episodes.[35] One was striking engineer George Watts, fatally shot in the temple by a deputized Burlington foreman on March 3, in Brookfield, Missouri.[36] Reports from Chicago at the end of March described riots, assaults, and arson of rolling stock and shop buildings.[37] On April 28, in Galesburg, Illinois, a strikebreaker named Albert Hedberg shot two Burlington strikers and claimed self-defense. One of those two, longtime Burlington engineer Herbert W. Newell, died from his wounds.[38]

On July 13 a criminal trial began for six saboteurs, held responsible for a series of dynamite attacks on the railroad. Another two were arrested on the 17th. Nobody was hurt in the explosions and failed attacks, which happened in and around Aurora and Galesburg, Illinois. One of the defendants, "J.Q. Wilson", was identified in court as an infiltrator named Mulligan working for the Pinkertons. Mulligan calmly changed sides in the courtroom and his charges were dropped.[39][40] Plotter and union official John A. Bauereisen received the longest sentence: two years.[41]

The two unions officially ended their strike unilaterally in January 1889. They both remained in operation and they both strongly oppose the Pullman Strike led by Debs in 1894, which also was a failure.