Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

Abu Nasr Ali ibn Ahmad Asadi Tusi (Persian: ابونصر علی بن احمد اسدی طوسی; c. 1000 – 1073) was a Persian poet, linguist and author. He was born at the beginning of the 11th century in Tus, Iran, in the province of Khorasan, and died in the late 1080s in Tabriz. Asadi Tusi is considered an important Persian poet of the Iranian national epics. His best-known work is Garshaspnameh, written in the style of the Shahnameh.[1]

Little is known about Asadi's life. Most of the Khorasan province was under violent attack by Turkish groups; many intellectuals fled, and those who remained generally lived in seclusion. Asadi spent his first twenty years in Ṭūs. From about 1018 to 1038 AD, he was a poet at the court of the Daylamite Abū Naṣr Jastān. Here, in 1055–56, Asadi copied Abū Manṣūr Mowaffaq Heravī's Ketāb al-abnīa al-adwīa. He later went to Nakhjavan and completed his seminal work, the Garshāsp-nama (dedicated to Abu Dolaf, ruler of Nakhjavan), in 1065–1066. Asadi then served at the court of the Shaddadid king Manuchehr, who ruled Ani. The poet's tomb is in the city of Tabriz.

Asadi's most significant work is Garshāsp-nama (The Book [or Epic] of Garshāsp). His other important contribution is a lexicon of the modern Persian language (Persian: فرهنگ لغت فرس). Five of Asadi's Monāẓarāt (Persian: مناظرات) (Debates in the form of poetry between two people or objects or concepts) also still exist.

The Garshaspnama (Persian: گرشاسپنامه) epic, with 9,000 couplets, is Asadi Tusi's major work. The hero of the poem is Garshasp (father of Kariman and great-grandfather of Šam), identified in the Shahnameh with the ancient Iranian hero Kərəsāspa- (Avestan language). In Avestan he was the son of Θrita- of the Yama clan. The poet adapted the story from a book, The Adventures of Garshāsp, saying that it complements the stories of the Shahnameh; although the poem was part of folklore, it was based on written sources.

The poem begins with Yama (or Jamshid), the father of Garshāsp, who was overthrown by Zahhak and flees to Ghurang, king of Zabulistan (near modern Quetta). In Zabulistan, Jamshid falls in love with the king's daughter and she gives birth to Garshāsp. Jamshid is forced to flee. When Garshāsp's mother poisons herself, he spends much of his life with his grandfather and grows up to be a warrior like Jamshid. After Ghurang's death Zahhak was to become king, although the secret remains until the birth of Kariman.

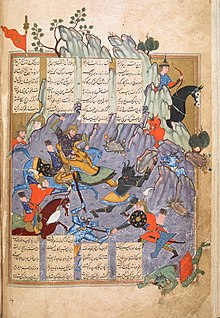

Zahhak, as king, visits Zābulistān and challenges the young Garshāsp to slay a dragon. Equipped with an antidote to dragon poison and armed with special weapons, Garshāsp kills the monster. Impressed with the child's prowess, Zahhāk sends Garshāsp to India, where the king (a vassal of Zahhāk's) has been replaced by the rebel prince Bahu (who does not acknowledge Zahhāk's rule). Garshāsp defeats the rebel and remains in India to observe its marvels and engage in philosophical discourse. He then goes to Sarandib (Ceylon), where he sees the footprint of the Buddha (in Muslim sources, identified with the footprint of Adam). Asadi then recounts many legends about Adam, the father of mankind. Garshasp then meets a Brahman, whom he questions in detail about philosophy and religion. The words Asadi Tusi attributes to the Brahman relate to his Islamic neo-Platonism. Garshasp later visits Indian islands and sees supernatural wonders, which are described at great length.

The hero returns home and pays homage to Zahak. He woos a princess of Rum, restores her father (Eṯreṭ) to his throne in Zābol after his defeat by the King of Kābol and builds the city of Sistān. He has anachronistic adventures in the Mediterranean, fighting in Kairouan and Córdoba. In the West, he meets a "Greek Brahman" and engages in philosophical discourse with the wise man.

When he returns to Iran his father dies, and Garshāsp becomes king of Zābolestān. Although he has no son of his own, he adopts Narēmān (Rostam's great-grandfather) as his heir. At this time Ferēdūn defeats Zahak and becomes king of Iran, and Garshāsp swears allegiance to him. Garshāsp and his nephew then go to Turan and defeat the Faghfūr of Chin (an Iranian title for the ruler of Central Asia and China, probably of Sogdian origin), bringing him as a captive to Ferēdūn. Garshāsp fights a final battle with the king of Tanger, slaying another dragon before he returns to Sistān in Zābolestān and dies.

The dictionary was written to familiarize the people of Arran and Iranian Azerbaijan with unfamiliar phrases in Eastern Persian (Darī) poetry. It is the oldest existing Persian dictionary based on examples from poetry, and contains fragments of lost literary works such as Kalila and Dimna by Rudaki and Vamiq and 'Adhra by Unsuri.[1] A variety of manuscripts exist in Iran and elsewhere; the oldest (1322) may be at the Malek Library in Tehran, although the one written in Safina-yi Tabriz is also from the same period.

Five debates survive in the Persian poetic form of qasida. Although this form of qasida is otherwise unprecedented in Arabic or New Persian, it is part of the Middle Persian (Pahlavi) tradition. The Pahlavic poetic debate Draxt i Asurik indicates the history of this form of debate. The surviving debates are Arab o 'Ajam (The Arab vs. the Persian), Mogh o Mosalman (The Zoroastrian vs. the Muslim), Shab o Ruz (Night vs. Day), Neyza o Kaman (Spear vs. Bow) and Asman o Zamin (Sky vs. Earth). The Persian wins the Persian-versus-Arab debate, while the Muslim defeats the Zoroastrian.