Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

Agarwood, aloeswood, eaglewood, gharuwood or the Wood of Gods, most commonly referred to as oud or oudh (from Arabic: عود, romanized: ʿūd, pronounced [ʕuːd]), is a fragrant, dark and resinous wood used in incense, perfume, and small hand carvings. It forms in the heartwood of Aquilaria trees after they become infected with a type of Phaeoacremonium mold, P. parasitica. The tree defensively secretes a resin to combat the fungal infestation. Prior to becoming infected, the heartwood mostly lacks scent, and is relatively light and pale in colouration. However, as the infection advances and the tree produces its fragrant resin as a final option of defense, the heartwood becomes very dense, dark, and saturated with resin. This product is harvested, and most famously referred to in cosmetics under the scent names of oud, oodh or aguru; however, it is also called aloes (not to be confused with the succulent plant genus Aloe), agar (this name, as well, is not to be confused with the edible, algae-derived thickening agent agar agar), as well as gaharu or jinko. With thousands of years of known use, and valued across Muslim, Christian, and Hindu communities (among other religious groups), oud is prized in Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures for its distinctive fragrance, utilized in colognes, incense and perfumes.

One of the main reasons for the relative rarity and high cost of agarwood is the depletion of the wild resource.[1] Since 1995, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora has listed Aquilaria malaccensis (the primary source) in its Appendix II (potentially threatened species).[2] In 2004, all Aquilaria species were listed in Appendix II; however, a number of countries have outstanding reservations regarding that listing.[2]

The varying aromatic qualities of agarwood are influenced by the species, geographic location, its branch, trunk and root origin, length of time since infection, and methods of harvesting and processing.[3]

Agarwood is one of the most expensive woods in the world, along with African blackwood, sandalwood, pink ivory and ebony.[4][5] First-grade agarwood is one of the most expensive natural raw materials in the world,[6] with 2010 prices for superior pure material as high as US$100,000/kg, although in practice adulteration of the wood and oil is common, allowing for prices as low as US$100/kg.[7] A wide range of qualities and products come to market, varying in quality with geographical location, botanical species, the age of the specific tree, cultural deposition and the section of the tree where the piece of agarwood stems from.[8] As of 2013 the global market for agarwood had an estimated value of US$6 to 8 billion and was growing rapidly.[9]

The word ultimately comes from one of the Dravidian languages,[10][11] probably from Tamil அகில் (akil).[12]

Agarwood is known under many names in different cultures:

The odour of agarwood is complex and pleasing,[26] with few or no similar natural analogues. In the perfume state, the scent is mainly distinguished by a combination of "oriental-woody" and "very soft fruity-floral" notes. The incense smoke is also characterised by a "sweet-balsamic" note and "shades of vanilla and musk" and amber (not to be confused with ambergris).[8] As a result, agarwood and its essential oil gained great cultural and religious significance in ancient civilizations around the world, being described as a fragrant product as early as 1400 BCE in the Vedas of India.[27]

In the Hebrew Bible, "trees of lign aloes" are mentioned in The Book of Numbers 24:6[28] and a perfume compounded of aloeswood, myrrh, and cassia is described in Psalms 45.[29]

Dioscorides in his book Materia Medica (65 CE) described several medical qualities of agarwood (Áγαλλοχου) and mentioned its use as an incense. Even though Dioscorides describes agarwood as having an astringent and bitter taste, it was used to freshen the breath when chewed or as a decoction held in the mouth. He also writes that a root extract was used to treat stomach complaints and dysentery as well as pains of the lungs and liver.[3] Agarwood's use as a medicinal product was also recorded in the Sahih Muslim, which dates back to approximately the ninth century, and in the Ayurvedic medicinal text the Susruta Samhita.[30]

As early as the third century CE in ancient Viet Nam, the Chinese chronicle Nan zhou yi wu zhi (Strange things from the South) written by Wa Zhen of the Eastern Wu Dynasty mentioned agarwood produced in the Rinan commandery, now Central Vietnam, and how people collected it in the mountains.

During the sixth century CE in Japan, in the recordings of the Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan) the second oldest book of classical Japanese history, mention is made of a large piece of fragrant wood identified as agarwood. The source for this piece of wood is claimed to be from Pursat, Cambodia (based on the smell of the wood). The famous piece of wood still remains in Japan today and is showcased less than 10 times per century at the Nara National Museum.

Agarwood is highly revered in Hinduism, Buddhism, Chinese Folk Religion and Islam.[3][31]

Starting in 1580 after Nguyễn Hoàng took control over the central provinces of modern Vietnam, he encouraged trade with other countries, specifically China and Japan. Agarwood was exported in three varieties: Calambac (kỳ nam in Vietnamese), trầm hương (very similar but slightly harder and slightly more abundant), and agarwood proper. A pound of Calambac bought in Hội An for 15 taels could be sold in Nagasaki for 600 taels. The Nguyễn Lords soon established a Royal Monopoly over the sale of Calambac. This monopoly helped fund the Nguyễn state finances during the early years of the Nguyen rule.[32] Accounts of international trade in agarwood date back as early as the thirteenth century, note India being one of the earliest sources of agarwood for foreign markets.[33]

Xuanzang's travelogues and the Harshacharita, written in seventh century AD in Northern India, mentions use of agarwood products such as 'Xasipat' (writing-material) and 'aloe-oil' in ancient Assam (Kamarupa). The tradition of making writing materials from its bark still exists in Assam.

It is to this day still used in traditional Chinese herbal medicine where it goes by the name of Chén Xiāng - 沉香 - Literally meaning 'sinking fragrance'. Its earliest recorded mention is from the Miscellaneous Records of Famous Physicians, 名医别录 , Ming Yi Bie Lu, ascribed to the author Táo Hǒng-Jǐng c.420-589.[34]

There are seventeen species in the genus Aquilaria, large evergreens native to southeast Asia and south asia, of which nine are known to produce agar wood.[35] Agarwood can in theory be produced from all members, but until recently it was primarily produced from A. malaccensis (A. agallocha and A. secundaria are synonyms for A. malaccensis).[1] A. crassna and A. sinensis are the other two members of the genus that are commonly harvested. The gyrinops tree can also produce agarwood.[36]

Agar wood forms in the trunk and roots of trees that have been penetrated by an Ambrosia beetle insect feeding on wood and oily resin, Dinoplatypus chevrolati. The tree may then be infected by a mould, and in response will produces a salutary self-defence material to conceal damages or infections. While the unaffected wood of the tree is relatively light in colour, the resin dramatically increases the mass and density of the affected wood, changing its colour from a pale beige to yellow, orange, red, dark brown or black. In natural forests, only about 7 out of 100 Aquilaria trees of the same species are infected and produce aloes/agar wood. A common method in planted forestry is to inoculate trees with the fungus. It produces a "damage sap" and is referred to as "fake" aloes/agar wood.[35]

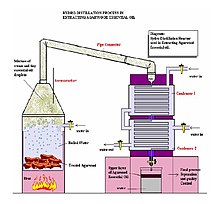

Oud oil can be distilled from agar wood using steam; the total yield of oil for 70 kg of wood will not exceed 20 ml.[37][full citation needed]

The composition of agarwood oil is exceedingly complex with more than 150 chemical compounds identified.[7] At least 70 of these are terpenoids which come in the form of sesquiterpenes and chromones; no monoterpenes have been detected at all. Other common classes of compounds include agarofurans, cadinanes, eudesmanes, valencanes and eremophilanes, guaianes, prezizanes, vetispiranes, simple volatile aromatic compounds as well as a range of miscellaneous compounds.[7] The exact balance of these materials will vary depending on the age and species of tree as well as the exact details of the oil extraction process.

Oud has become a popular component in perfumery. Most brands have a creation based on or dedicated to "oud" or an accord of oud created through the use of certain chemical scent components. Few perfume houses use real oud in their creations. This is because oud is very expensive and potent. Oud is generally used as a base note and is traditionally paired with rose. Oud essential oil is available on the internet but care should be taken in choosing the vendor. Due to the fact that oud is such an expensive material there is a big market for diluting oud oil with patchouli or other chemical components.

Oud scent is popular in the Middle East, the Arab world, and in Arab culture, where it is used as a traditional aromatic and perfume in many forms. Oud is also one of the reasons why the Arab region developed trade routes in ancient times. Popular amongst Muslims, it has been traditionally used in Mosques where the incense chips are burned.[38]

The following species of Aquilaria produce agarwood:[35]

* Sri Lankan agarwood is known as Walla Patta and is of the Gyrinops walla species.

Overharvesting and habitat loss threatens some populations of agarwood-producing species. Concern over the impact of the global demand for agarwood has thus led to the inclusion of the main taxa on CITES Appendix II, which requires that international trade in agarwood be monitored. Monitoring is conducted by Cambridge-based TRAFFIC (a joint WWF and IUCN programme).[41] CITES also provides that international trade in agarwood be subject to controls designed to ensure that harvest and exports are not to the detriment of the survival of the species in the wild.[42]

In addition, agarwood plantations have been established in a number of countries, and reintroduced into countries such as Malaysia and Sri Lanka as commercial plantation crops.[41] The success of these plantations depends on the stimulation of agarwood production in the trees. Numerous inoculation techniques have been developed, with varying degrees of success.[35]

Ta. akil (in cpds. akiṛ-) eagle-wood, Aquilaria agallocha; the drug agar obtained from the tree; akku eagle-wood. Ma. akil aloe wood, A. agallocha. Ka. agil the balsam tree which yields bdellium, Amyris agallocha; the dark species of Agallochum; fragrance. Tu. agilů a kind of tree; kari agilů Agallochum. / Cf. Skt. aguru-, agaru-; Pali akalu, akaḷu, agaru, agalu, agaḷu; Turner, CDIAL, no. 49. DED 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

agaru m.n. ʻ fragrant Aloe -- tree and wood, Aquilaria agallocha ʼ lex., aguru -- R. [← Drav. Mayrhofer EWA i 17 with lit.] Pa. agalu -- , aggalu -- m., akalu -- m. ʻ a partic. ointment ʼ; Pk. agaru -- , agaluya -- , agaru(a) -- m.n. ʻ Aloe -- tree and wood ʼ; K. agara -- kāth ʻ sandal -- wood ʼ; S. agaru m. ʻ aloe ʼ, P. N. agar m., A. B. agaru, Or. agarū, H. agar, agur m.; G. agar, agru n. ʻ aloe or sandal -- wood ʼ; M. agar m.n. ʻ aloe ʼ, Si. ayal (agil ← Tam. akil).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

We have ahalim [in Hebrew], probably derived directly from Tamil akil rather than from Sanskrit aguru, itself a loan from the Tamil (Numbers 24.8; Proverbs 7.17; Song of Songs 4.14; Psalms 45.9--the latter two instances with the feminine plural form ahalot. Akil is, we think, native to South India, and it is thus not surprising that the word was borrowed by cultures that imported this plant.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

Snelder, Denyse J.; Lasco, Rodel D. (29 September 2008). Smallholder Tree Growing for Rural Development and Environmental Services: Lessons from Asia. シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社. p. 248 ff. ISBN 978-1-4020-8260-3. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

Jung, Dr. Dinah (1 January 2013). The cultural biography of agarwood (PDF). University of Heidelberg: HeiDOK: Journal article: JRAS. pp. 103–125. Retrieved 30 October 2016.