Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

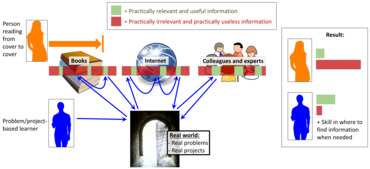

Project-based learning is a teaching method that involves a dynamic classroom approach in which it is believed that students acquire a deeper knowledge through active exploration of real-world challenges and problems.[1] Students learn about a subject by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to a complex question, challenge, or problem.[2] It is a style of active learning and inquiry-based learning. Project-based learning contrasts with paper-based, rote memorization, or teacher-led instruction that presents established facts or portrays a smooth path to knowledge by instead posing questions, problems, or scenarios.[3]

History

John Dewey is recognized as one of the early proponents of project-based education or at least its principles through his idea of "learning by doing".[4] In My Pedagogical Creed (1897) Dewey enumerated his beliefs including the view that "the teacher is not in the school to impose certain ideas or to form certain habits in the child, but is there as a member of the community to select the influences which shall affect the child and to assist him in properly responding to these".[5] For this reason, he promoted the so-called expressive or constructive activities as the centre of correlation.[5] Educational research has advanced this idea of teaching and learning into a methodology known as "project-based learning". William Heard Kilpatrick built on the theory of Dewey, who was his teacher, and introduced the project method as a component of Dewey's problem method of teaching.[6]

Some scholars (e.g. James G. Greeno) also associated project-based learning with Jean Piaget's "situated learning" perspective[7] and constructivist theories. Piaget advocated an idea of learning that does not focus on memorization. Within his theory, project-based learning is considered a method that engages students to invent and to view learning as a process with a future instead of acquiring knowledge bases as a matter of fact.[8]

Further developments to project-based education as a pedagogy later drew from the experience- and perception-based theories on education proposed by theorists such as Jan Comenius, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and Maria Montessori, among others.[6]

Concept

In 2011, Thomas Markham described project-based learning as follows:

"integrates knowing and doing. Students learn knowledge and elements of the core curriculum but also apply what they know to solve authentic problems and produce results that matter. Project-based learning students take advantage of digital tools to produce high-quality, collaborative products. Project-based learning refocuses education on the student, not the curriculum—a shift mandated by the global world, which rewards intangible assets such as drive, passion, creativity, empathy, and resilience. These cannot be taught out of a textbook, but must be activated through experience."[9]

Problem-based learning is a similar pedagogic approach; however, problem-based approaches structure students' activities more by asking them to solve specific (open-ended) problems rather than relying on students to come up with their own problems in the course of completing a project. Another seemingly similar approach is quest-based learning; unlike project-based learning, in questing, the project is determined specifically on what students find compelling (with guidance as needed), instead of the teacher being primarily responsible for forming the essential question and task.[10]

Blumenfeld et al. elaborate on the processes of Project-based learning: "Project-based learning is a comprehensive perspective focused on teaching by engaging students in investigation. Within this framework, students pursue solutions to nontrivial problems by asking and refining questions, debating ideas, making predictions, designing plans and/or experiments, collecting and analyzing data, drawing conclusions, communicating their ideas and findings to others, asking new questions, and creating artifacts."[11] The basis of Project-based learning lies in the authenticity or real-life application of the research. Students working as a team are given a "driving question" to respond to or answer, then directed to create an artifact (or artifacts) to present their gained knowledge. Artifacts may include a variety of media such as writings, art, drawings, three-dimensional representations, videos, photography, or technology-based presentations.

Another definition of project-based learning includes a type of instruction where students work together to solve real-world problems in their schools and communities. This type of problem-solving often requires students to draw on lessons from several disciplines and apply them in a very practical way and the promise of seeing a very real impact becomes the motivation for learning.[12] In addition to learning the content of their core subjects, students have the potential to learn to work in a community, thereby taking on social responsibilities.

According to Terry Heick on his blog, TeachThought, there are three types of project-based learning.[13] The first is challenge-based learning/problem-based learning, the second is place-based education, and the third is activity-based learning. Challenge-based learning is "an engaging multidisciplinary approach to teaching and learning that encourages students to leverage the technology they use in their daily lives to solve real-world problems through efforts in their homes, schools and communities." Place-based education "immerses students in local heritage, cultures, landscapes, opportunities and experiences; uses these as a foundation for the study of language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects across the curriculum, and emphasizes learning through participation in service projects for the local school and/or community." Activity-based learning takes a kind of constructivist approach, the idea being students constructing their own meaning through hands-on activities, often with manipulatives and opportunities to experiment.

Structure

Project-based learning emphasizes learning activities that are long-term, interdisciplinary, and student-centered. Unlike traditional, teacher-led classroom activities, students often must organize their own work and manage their own time in a project-based class. Project-based instruction differs from traditional inquiry by its emphasis on students' collaborative or individual artifact construction to represent what is being learned. Design principles thus emphasize "student agency, authenticity, and collaboration."[14]

Project-based learning also gives students the opportunity to explore problems and challenges that have real-world applications, increasing the possibility of long-term retention of skills and concepts.[15]

Elements

The core idea of project-based learning is that real-world problems capture students' interest and provoke serious thinking as the students acquire and apply new knowledge in a problem-solving context. The teacher plays the role of facilitator, working with students to frame worthwhile questions, structuring meaningful tasks, coaching both knowledge development and social skills, and carefully assessing what students have learned from the experience. Typical projects present a problem to solve (What is the best way to reduce the pollution in the schoolyard pond?) or a phenomenon to investigate (What causes rain?). Project-based learning replaces other traditional models of instruction such as lectures, textbook-workbook-driven activities and inquiry as the preferred delivery method for key topics in the curriculum. It is an instructional framework that allows teachers to facilitate and assess deeper understanding rather than stand and deliver factual information. Project-based learning intentionally develops students' problem-solving and the creative making of products to communicate a deeper understanding of key concepts and mastery of 21st-century essential learning skills such as critical thinking. Students become active digital researchers and assessors of their own learning when teachers guide student learning so that students learn from the project-making processes. In this context, Project-based learning is units of self-directed learning from students' doing or making throughout the unit. Project-based learning is not just "an activity" (project) that is stuck at the end of a lesson or unit.[16]

Comprehensive project-based learning:

- is organized around an open-ended driving question or challenge.

- creates a need to know essential content and skills.

- requires inquiry to learn and/or create something new.

- requires critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and various forms of communication, often known as 21st century skills.

- allows some degree of student voice and choice.

- incorporates feedback and revision.

- results in a publicly presented product or performance.[17]

Examples

Although projects are the primary vehicle for instruction in project-based learning, there are no commonly shared criteria for what constitutes an acceptable project. Projects vary greatly in the depth of the questions explored, the clarity of the learning goals, the content and structure of the activity, and guidance from the teacher. The role of projects in the overall curriculum is also open to interpretation. Projects can guide the entire curriculum (more common in charter or other alternative schools) or simply consist of a few hands-on activities. They might be multidisciplinary (more likely in elementary schools) or single-subject (commonly science and math). Some projects involve the whole class, while others are done in small groups or individually. For example, Perrault and Albert[18] report the results of a Project-based learning assignment in a college setting surrounding creating a communication campaign for the campus' sustainability office, finding that after project completion in small groups that the students had significantly more positive attitudes toward sustainability than prior to working on the projects.

Another example is Manor New Technology High School, a public high school that since opening in 2007 is a 100 percent project-based instruction school. Students average 60 projects a year across subjects. It is reported that 98 percent of seniors graduate, 100 percent of the graduates are accepted to college, and fifty-six percent of them have been the first in their family to attend college.[19]

Outside of the United States, the European Union has also providing funding for project-based learning projects within the Lifelong Learning Programme 2007–2013. In China, Project-based learning implementation has primarily been driven by international school offerings,[20] although public schools use Project-based learning as a reference for Chinese Premier Ki Keqiang's mandate for schools to adopt maker education,[21] in conjunction with micro-schools like Moonshot Academy and ETU, and maker education spaces such as SteamHead.[22]

In Uganda since the introduction of the new lower curriculum,[23] students and teachers have been urged to embraced project based learning especially with training from the Ugandan Government[24] and UNELTA[25]

Roles

Project-based learning often relies on learning groups, but not always. Student groups may determine their projects, and in so doing, they engage student voice by encouraging students to take full responsibility for their learning.

When students use technology as a tool to communicate with others, they take on an active role vs. a passive role of transmitting the information by a teacher, a book, or broadcast. The student is constantly making choices on how to obtain, display, or manipulate information. Technology makes it possible for students to think actively about the choices they make and execute. Every student has the opportunity to get involved, either individually or as a group.

The instructor's role in project-based learning is that of a facilitator. They do not relinquish control of the classroom or student learning, but rather develop an atmosphere of shared responsibility. The instructor must structure the proposed question/issue so as to direct the student's learning toward content-based materials. Upfront planning is crucial, in that the instructor should plan out the structural elements and logistics of the project far in advance in order to reduce student confusion once they assume ownership of their projects.[26] The instructor must regulate student success with intermittent, transitional goals to ensure student projects remain focused and students have a deep understanding of the concepts being investigated. The students are held accountable to these goals through ongoing feedback and assessments. The ongoing assessment and feedback are essential to ensure the student stays within the scope of the driving question and the core standards the project is trying to unpack. According to Andrew Miller of the Buck Institute of Education, "In order to be transparent to parents and students, you need to be able to track and monitor ongoing formative assessments that show work toward that standard."[27] The instructor uses these assessments to guide the inquiry process and ensure the students have learned the required content. Once the project is finished, the instructor evaluates the finished product and the learning that it demonstrates.

The student's role is to ask questions, build knowledge, and determine a real-world solution to the issue/question presented. Students must collaborate, expanding their active listening skills and requiring them to engage in intelligent, focused communication, therefore allowing them to think rationally about how to solve problems. Project-based learning forces students to take ownership of their success.

In the digital and remote learning era, traditional roles have adapted to incorporate virtual collaboration. Instructors now serve as digital facilitators, using online platforms to monitor progress and provide asynchronous feedback, while students must develop both project and digital management skills. This transformation has introduced new team dynamics, with students taking on specific digital responsibilities such as managing online repositories and coordinating virtual communication.

Outcomes

Proponents of project-based learning cite numerous benefits to the implementation of its strategies in the classroom – including a greater depth of understanding of concepts, a broader knowledge base, improved communication, and interpersonal/social skills, enhanced leadership skills, increased creativity, and improved writing skills.

Some of the most significant contributions of Project-based learning have been in schools of comparative disadvantage where it has been linked to increased self-esteem, better work habits, and more positive attitudes toward learning.The pedagogical practice is also linked to conversations revolving around equitable instruction, as it presents opportunities to provide learning experiences that are "equitable, relevant, and meaningful to each and every student while supporting the development of not only students' academic learning, but also their social, emotional, and identity development."[14]

Teachers who implement Project-Based Learning assert that this approach emphasizes teachers helping their students track and develop their own processes of thinking, making them more aware of problem-solving strategies they can use in the future.[26]

Blumenfeld & Krajcik (2006) cited studies that show students in project-based learning classrooms obtain higher test scores than students in traditional classroom.[29]

Student-choice and autonomy may contribute to students growing more heavily interested in the subject, as discovered by researchers in a 2019 study in which they evaluated student engagement in a Project-Based after-school program. After learning more about environmental concerns and implementing a small scale community project, students in this program reported more positive attitudes towards science and literacy.[30]

Criticism

Opponents of project-based learning caution against negative outcomes primarily in projects that become unfocused, as underdeveloped assignments or lessons may result in the waste of class time and inability to achieve the learning objectives. Since Project-based learning revolves around student autonomy, student's self-motivation and ability to balance work time both inside and outside of school are imperative to a successful project and teachers may be challenged to present students with sufficient time, flexibility, and resources to be successful.[31] Furthermore, "Keeping these complex projects on track while attending to students' individual learning needs...requires artful teaching, as well as industrial-strength project management."[32]

See also

References

- ^ Project-Based Learning, Edutopia, March 14, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-15

- ^ What is PBL? Buck Institute for Education. Retrieved 2016-03-15

- ^ Yasseri, Dar; Finley, Patrick M.; Mayfield, Blayne E.; Davis, David W.; Thompson, Penny; Vogler, Jane S. (2018-06-01). "The hard work of soft skills: augmenting the project-based learning experience with interdisciplinary teamwork". Instructional Science. 46 (3): 457–488. doi:10.1007/s11251-017-9438-9. ISSN 1573-1952. S2CID 57862265.

- ^ Bender, William N. (2012). Project-Based Learning: Differentiating Instruction for the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4522-7927-5.

- ^ a b John Dewey, Education and Experience, 1938/1997. New York. Touchstone.

- ^ a b Beckett, Gulbahar; Slater, Tammy (2019). Global Perspectives on Project-Based Language Learning, Teaching, and Assessment: Key Approaches, Technology Tools, and Frameworks. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-78695-2.

- ^ Greeno, J. G. (2006). Learning in activity. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 79-96). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Sarrazin, Natalie R. (2018). Problem-Based Learning in the College Music Classroom. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-26522-5.

- ^ Markham, T. (2011). Project-Based Learning. Teacher Librarian, 39(2), 38-42.

- ^ Alcock, Marie; Michael Fisher; Allison Zmuda (2018). The Quest for Learning: How to Maximize Student Engagement. Bloomington: Solution Tree.

- ^ Blumenfeld et al 1991, EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST, 26(3&4) 369-398 "Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learning." Phyllis C. Blumenfeld, Elliot Soloway, Ronald W. Marx, Joseph S. Krajcik, Mark Guzdial, and Annemarie Palincsar.

- ^ "Education World".

- ^ Heick, Terry (August 2, 2018). "3 Types Of Project-Based Learning Symbolize Its Evolution"

- ^ a b Tierney, Gavin; Urban, Rochelle; Olabuenaga, Gina (2023). "Designing for Equity: Moving Project-Based Learning From Equity Adjacent to Equity Infused".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Crane, Beverley (2009). Using Web 2.0 Tools in the K-12 Classroom. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-55570-653-1.

- ^ "How to use Project-Based Learning approach to build learning environments". teachfloor.com. 2022-04-02.

- ^ "Seven Essentials for Project-Based Learning".

- ^ Perrault, Evan K.; Albert, Cindy A. (2017-10-04). "Utilizing project-based learning to increase sustainability attitudes among students". Applied Environmental Education & Communication. 17 (2): 96–105. doi:10.1080/1533015x.2017.1366882. ISSN 1533-015X. S2CID 148880970.

- ^ Makes Project-Based Learning a Success?. Retrieved 2013-10-29

- ^ [1]. Larmer, John (2018)

- ^ "Making China: Cultivating Entrepreneurial Living | Center on Contemporary China".

- ^ [2] Xin Hua News, referenced 2017.

- ^ says, Droku Benbella (2024-02-29). "'Despite challenges, schools have embraced the new curriculum' – Economic Policy Research Centre". Retrieved 2024-07-08.

- ^ "Teachers must be trained for new lower curriculum to succeed". New Vision. Retrieved 2024-07-08.

- ^ "UNELTA". UNELTA. Retrieved 2024-07-08.

- ^ a b Tawfik, Andrew A.; Gishbaugher, Jaclyn J.; Gatewood, Jessica; Arrington, T. Logan (2021-08-17). "How K-12 Teachers Adapt Problem-Based Learning Over Time". Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. 15 (1). doi:10.14434/ijpbl.v15i1.29662. ISSN 1541-5015.

- ^ Miller, Andrew. "Edutopia". © 2013 The George Lucas Educational Foundation. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD, using source images by various authors. Source for useful context in problem-based learning: Mark A Albanese, Laura C Dast (2013-10-22). "Understanding Medical Education - Problem-based learning". Wiley Online Library. doi:10.1002/9781118472361.ch5.

- ^ Sawyer, R. K. (2006) The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Farmer, Rachel; Greene, NaKayla; Perry, Kristen H; Jong, Cindy (2019-11-11). "Environmental Explorations: Integrating Project-Based Learning and Civic Engagement Through an Afterschool Program". Journal of Educational Research and Practice. 9 (1). doi:10.5590/JERAP.2019.09.1.30. ISSN 2167-8693.

- ^ Ramos-Ramos, Pablo; Botella Nicolás, Ana María (2022-08-31). "Teaching Dilemmas and Student Motivation in Project-based Learning in Secondary Education". Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. 16 (1). doi:10.14434/ijpbl.v16i1.33056. ISSN 1541-5015.

- ^ "Projects and Partnerships Build a Stronger Future - Edutopia". edutopia.org.

Notes

- John Dewey, Education and Experience, 1938/1997. New York. Touchstone.

- Hye-Jung Lee1, h., & Cheolil Lim1, c. (2012). Peer Evaluation in Blended Team Project-Based Learning: What Do Students Find Important?. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 214-224.

- Markham, T. (2011). Project Based Learning. Teacher Librarian, 39(2), 38-42.

- Blumenfeld et al. 1991, EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST, 26(3&4) 369-398 "Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learning." Phyllis C. Blumenfeld, Elliot Soloway, Ronald W. Marx, Joseph S. Krajcik, Mark Guzdial, and Annemarie Palincsar.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2006), The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Buck Institute for Education (2009). PBL Starter Kit: To-the-Point Advice, Tools and Tips for Your First Project. Introduction chapter free to download at: https://web.archive.org/web/20101104022305/http://www.bie.org/tools/toolkit/starter

- Buck Institute for Education (2003). Project Based Learning Handbook: A Guide to Standards-Focused Project Based Learning for Middle and High School Teachers. Introduction chapter free to download at: https://web.archive.org/web/20110122135305/http://www.bie.org/tools/handbook

- Barron, B. (1998). Doing with understanding: Lessons from research on problem- and project-based learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 7 (3&4), 271-311.

- Blumenfeld, P.C. et al. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26, 369-398.

- Boss, S., & Krauss, J. (2007). Reinventing project-based learning: Your field guide to real-world projects in the digital age. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

- Falk, B. (2008). Teaching the way children learn. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Katz, L. and Chard, S.C.. (2000) Engaging Children's Minds: The Project Approach (2d Edition), Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

- Keller, B. (2007, September 19). No Easy Project. Education Week, 27(4), 21-23. Retrieved March 25, 2008, from Academic Search Premier database.

- Knoll, M. (1997). The project method: its origin and international development. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education 34 (3), 59-80.

- Knoll, M. (2012). "I had made a mistake": William H. Kilpatrick and the Project Method. Teachers College Record 114 (February), 2, 45 pp.

- Knoll, M. (2014). Project Method. Encyclopedia of Educational Theory and Philosophy, ed. C.D. Phillips. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Vol. 2., pp. 665–669.

- Shapiro, B. L. (1994). What Children Bring to Light: A Constructivist Perspective on Children's Learning in Science; New York. Teachers College Press.

- Helm, J. H., Katz, L. (2001). Young investigators: The project approach in the early years. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Mitchell, S., Foulger, T. S., & Wetzel, K., Rathkey, C. (February, 2009). The negotiated project approach: Project-based learning without leaving the standards behind. Early Childhood Education Journal, 36(4), 339-346.

- Polman, J. L. (2000). Designing project-based science: Connecting learners through guided inquiry. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Reeves, Diane Lindsey STICKY LEARNING. Raleigh, North Carolina: Bright Futures Press, 2009. [3].

- Foulger, T.S. & Jimenez-Silva, M. (2007). "Enhancing the writing development of English learners: Teacher perceptions of common technology in project-based learning". Journal of Research on Childhood Education, 22(2), 109-124.

- Shaw, Anne. 21st Century Schools.

- Wetzel, K., Mitchell-Kay, S., & Foulger, T. S., Rathkey, C. (June, 2009). Using technology to support learning in a first grade animal and habitat project. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning.

- Heick, Terry. (2013). 3 Types of Project-Based Learning Symbolize Its Evolution. Available at http://www.teachthought.com/learning/5-types-of-project-based-learning-symbolize-its-evolution/

External links

- PBLWorks – from the Buck Institute for Education

- North Lawndale College Prep High School's Interdisciplinary Projects – vertically aligned, high-bar problem- and project-based learning, 9–12, on Chicago's west side.

- Top Ten Tips for Assessing Project-Based Learning – from Edutopia by the George Lucas Educational Foundation.

- Testing the Water: project-based learning and high standards at Shutesbury Elementary School – from Edutopia by the George Lucas Educational Foundation.

- Intel Teach Elements: Project-Based Approaches is a free, online professional development course that explores project-based learning.

- Project Work in (English) Language Teaching provides a practical guide to running a successful 30-hour (15-lesson) short film project in English with (pre-)intermediate students: planning, lessons, evaluation, deliverables, samples and experiences, plus ideas for other projects.

- The 4Cs of Learning provides a guide for integration aspects of project-based learning.