Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

Philology, the study of comparative and historical linguistics, especially of the medieval period, had a major influence on J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth. He was a professional philologist, and made use of his knowledge of medieval literature and language to create families of Elvish languages and many details of the invented world.

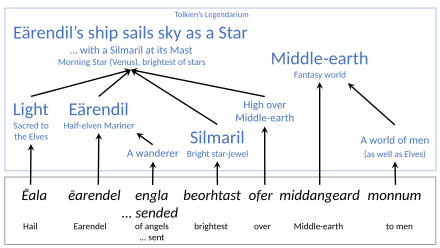

Among the medieval sources for Middle-earth are Crist 1, which led to the tale of Eärendil, the beginning of Tolkien's mythology; Beowulf, which he used in many places; his philological study of the Old English word Sigelwara, which may have inspired the Silmarils, Balrogs, and the Haradrim; and his research on an inscription at the temple of Nodens, which seems to have led to Celebrimbor Silver-hand, maker of the Rings of Power, to Dwarves, and to the One Ring itself.

His use of his philological understanding of language in the construction of his Middle-earth legendarium was pervasive, beginning with his families of Elvish languages. From there, he created elements of story, including the history and geography of Middle-earth, the names of people and places, and eventually a complete mythology.

Context

From his schooldays, J. R. R. Tolkien was in his biographer John Garth's words "effusive about philology"; his schoolfriend Rob Gilson called him "quite a great authority on etymology".[2] Tolkien was a professional philologist, a scholar of comparative and historical linguistics. He was especially familiar with Old English and related languages. He remarked to the poet and The New York Times book reviewer Harvey Breit that "I am a philologist and all my work is philological"; he explained to his American publisher Houghton Mifflin that this was meant to imply that his work was "all of a piece, and fundamentally linguistic in inspiration. ... The invention of languages is the foundation. The 'stories' were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse. To me a name comes first and the story follows."[T 1]

The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger writes that Tolkien's "profession as philologist and his vocation as writer of fantasy/theology overlapped and mutually supported one another",[3] in other words that he "did not keep his knowledge in compartments; his scholarly expertise informs his creative work."[4] This expertise was founded, in her view, on the belief that one knows a text only by "properly understanding [its] words, their literal meaning and their historical development."[3] She states that he skilfully exploited the language styles of different characters to situate them geographically as well as in their specific culture and their psychological makeup, commenting that, "One can imagine a seventy-page essay centuries hence on 'Tolkien as a Philologist: The Lord of the Rings'".[4]

Medieval sources

Crist 1

-

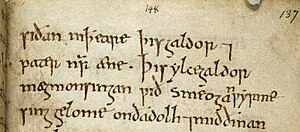

Ēala ēarendel engla beorhtast / ofer middangeard monnum sended,

"Hail Earendel, brightest of angels, over Middle-earth to men sent"

(second half of top line, first half of second line) - part of the poem Crist 1 in the Exeter Book, folio 9v, top[5]

It has been called "the catalyst for Tolkien's mythology".[6][7]

Tolkien began his mythology with the 1914 poem The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star, inspired by the Old English poem Crist 1.[6][8] Around 1915, he had the idea that his constructed language Quenya was to be spoken by Elves whom the character Eärendil meets during his journeys.[9] From there, he wrote the Lay of Earendel, telling of Earendel and his voyages and how his ship turned into the morning star.[10][11][5][12] These lines from Crist 1 also gave Tolkien the term Middle-earth (translating Old English Middangeard). Accordingly, the medievalists Stuart D. Lee and Elizabeth Solopova state that Crist 1 was "the catalyst for Tolkien's mythology".[6][7][8]

Beowulf

Tolkien was an expert on Old English literature, especially the epic poem Beowulf, and made many uses of it in The Lord of the Rings. For example, Beowulf's list of creatures, eotenas ond ylfe ond orcnéas, "Ettens [giants] and Elves and demon-corpses", contributed to his creation of some of the races of beings in Middle-earth.[13]

He derived the Ents from a phrase in another Old English poem, Maxims II, orþanc enta geweorc, "skilful work of giants".[15] The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey suggests that Tolkien took the name of the tower of Orthanc (orþanc) from the same phrase, reinterpreted as "Orthanc, the Ents' fortress".[14]

The word orþanc occurs again in Beowulf in the phrase searonet seowed, smiþes orþancum, "[a mail-shirt, a] cunning-net sewn, by a smith's skill": Tolkien used searo in its Mercian form *saru for the name of Orthanc's ruler, the wizard Saruman, "cunning man", incorporating the ideas of skill and technology into Saruman's character.[16] He made use of Beowulf, too, along with other Old English sources, for many aspects of the Riders of Rohan. They called their land the Mark, a version of the Mercia where he lived, in Mercian dialect *Marc.[17]

In the case of Tolkien's description of the floor of Meduseld, the hall of King Théoden of Rohan in The Lord of the Rings, the folklorist and Tolkien scholar Dimitra Fimi suggests that it is possible to trace Tolkien's thought back to an actual medieval floor. In a 1926 review of an article about placenames and archaeology, Tolkien wrote that the phrase on fāgne flōr, "on the bright-patterned floor", occurs in Beowulf, line 725. He commented that it "might be guessed to mean paved or even tessellated floor."[T 2] Tolkien, describing himself rhetorically as "the philologist", notes that the Oxfordshire village of Fawler was in 1205 named Fauflor;[a] that he would wonder if that meant there was a Roman villa nearby; and that "the archaeologist" would reply that there was indeed one "with a tessellated pavement" near there, the large and luxurious North Leigh Roman Villa.[T 2][19][20] Fimi writes that the Beowulf lines are definitely echoed in Tolkien's description of the hall of King Théoden of Rohan in The Lord of the Rings, and "perhaps even this image of the real floor" too.[20]

| Beowulf, lines 723–725 | Tolkien's prose translation[T 3] | "The King of the Golden Hall"[T 4] | A "bright-patterned floor" at a village named after it[T 2][19] |

|---|---|---|---|

onbraéd þá bealo-hýdig, þá hé gebolgen wæs, |

He [Grendel] wrenched then wide, baleful with raging heart, the gaping entrance of the house; then swift on the bright-patterned floor the demon paced. | The hall was long and wide and filled with shadows and half lights; mighty pillars upheld its lofty roof… As their eyes changed, the travellers perceived that the floor was paved with stones of many hues; branching runes and strange devices intertwined beneath their feet. |

|

Sigelwara

Several Middle-earth concepts may have come from the Old English word Sigelwara, used in the Codex Junius to mean "Aethiopian".[22][23][24] Tolkien wondered why there was a word with this meaning, given that the Anglo-Saxons had had little or no contact with peoples of Africa. Accordingly, he conjectured that it had once had a different meaning, which he explored in detail in his philological essay "Sigelwara Land", published in two parts in 1932 and 1934.[T 5] He stated that Sigel meant "both sun and jewel", the former as it was the name of the sun rune *sowilō (ᛋ), the latter from Latin sigillum, a seal.[21]

He decided that the second element was *hearwa, possibly related to Old English heorð, "hearth", and ultimately to Latin carbo, "soot". He suggested, in what he admitted was a philological conjecture, that this implied "rather the sons of Muspell [a fiery realm in Germanic myth] than of Ham [Biblical Africans]".[T 5] In other words, he supposed, the Sigelwara named a class of demons "with red-hot eyes that emitted sparks and faces black as soot".[T 5] Shippey states that this "helped to naturalise the Balrog" (a demon of fire) and contributed to the sun-jewel Silmarils.[23] Further, the Anglo-Saxon mention of Aethiopians suggested to Tolkien the Haradrim, a dark southern race of men.[b][T 6]

Nodens

In 1928, a 4th-century pagan cult temple was excavated at Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.[25] Tolkien was asked to conduct a philological investigation of a Latin inscription there, translating it as: "For the god Nodens. Silvianus has lost a ring and has donated one-half [its worth] to Nodens. Among those who are called Senicianus do not allow health until he brings it to the temple of Nodens."[26] An old name for the place was "Dwarf's Hill", and in 1932, Tolkien traced Nodens to the Irish hero Nuada Airgetlám, "Nuada of the Silver-Hand".[T 7]

Shippey thought this "a pivotal influence" on Tolkien's Middle-earth, combining as it did a god-hero, a ring, dwarves, and a silver hand.[1] The J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia notes also the "Hobbit-like appearance of [Dwarf's Hill]'s mine-shaft holes", and that Tolkien was extremely interested in the hill's folklore on his stay there, citing Helen Armstrong's comment that the place may have inspired Tolkien's "Celebrimbor and the fallen realms of Moria and Eregion".[1][27] The Lydney curator Sylvia Jones said that Tolkien was "surely influenced" by the site.[28] The scholar of English literature John M. Bowers notes that the name of the Elven-smith Celebrimbor is the Sindarin for "Silver Hand", and that, "Because the place was known locally as Dwarf's Hill and honeycombed with abandoned mines, it naturally suggested itself as background for the Lonely Mountain and the Mines of Moria."[29]

A pervasive influence

Tolkien was constantly inspired in his writing of fiction by his professional work in philology. The Tolkien scholar John D. Rateliff gives a few examples among many: his use of the Poetic Edda for the names of Dwarves in The Hobbit; of the Beowulf scene where a cup is stolen from the dragon's hoard, for Bilbo's venture into Smaug's lair; and his construction of the mythic tale of Earendil from the Old English name Earendel. His creation took many forms.[30]

Inventing languages and people to speak them

Tolkien took a special pleasure, described in his 1931 essay "A Secret Vice",[T 9] in inventing languages.[31] He invested a large amount of time and energy creating philologically-structured language families, especially the Elvish languages of Quenya and Sindarin, both of which appear in The Lord of the Rings.[32] Thus, the word for "Elves" in one language variant, Common Eldarin, was kwendi, its consonants realistically and systematically modified into quendi in Quenya, penni in Silvan, pendi in Telerin, and penidh in Sindarin.[32][T 8]

The existence of all these languages motivated his creation of a mythology; the languages needed people to speak them, and they in turn needed history and geography, wars and migrations.[32] In The Silmarillion, these include the sundering of the Elves, their repeated splintering into separate groups neatly mirroring the fragmentation of Quenya into languages and dialects.[33] Tolkien stated as much in his foreword to the Second Edition of The Lord of the Rings: "I wished first to complete and set in order the mythology and legends of the Elder Days ... for my own satisfaction ... it was primarily linguistic in inspiration and was begun in order to provide the necessary background of 'history' for Elvish tongues".[T 10]

Inventing a mythology

The scholar of folklore Tommy Kuusela writes that Tolkien's intention to create a mythology for England,[T 11] noted by other scholars,[35][36][37] was based on his nation's evident lack of anything like the tradition in Finnish, Greek, or Norse mythology and folklore.[38] Tolkien admitted as much in his 1936 lecture, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics", suggesting that England's lost mythology must have been something like the surviving Norse myths.[38] He could not do what Elias Lönnrot did in Finland, for example: travel the countryside to gather folk tales surviving in oral tradition, and assemble them into a genuine national mythology like the Kalevala. Instead, he was driven to invent, making use of whatever materials he could find: philological hints and clues in medieval literature, as well as story elements from non-English mythologies.[38] His method was always to look for the hidden or missing using his knowledge of philology: "The asterix [conjectured wordform], the root and the recreated word become, in Tolkien's mind, the seeds for a narrative."[38] At the most, he could suppose that some of the material in his legendarium "already existed; it was something originating in a collective English imagination, and he was in that sense not inventing things from scratch."[38]

With so little information about what English mythology might have been, Tolkien was forced to combine scraps from whatever sources he could find. An instance of this is his reconstruction of Elves, based on clues from such Old English sources as had survived, combined with clues from further afield, such as Norse mythology.[13]

| Medieval source | Philological clue | Idea |

|---|---|---|

| Beowulf | eotenas ond ylfe ond orcnéas: "ettens, elves, and devil-corpses" | Elves are strong and dangerous. |

| Sir Gawain and the Green Knight | The Green Knight is an aluisch mon: "elvish man, uncanny creature" | Elves have strange powers. |

| Magical spell | ofscoten: "elf-shot" (causing sickness, to be treated with the spell) | Elves are archers. |

| Icelandic and Old English usage |

frið sem álfkona: "fair as an elf-woman" ælfscýne: "elf-beautiful" |

Elves are beautiful. |

| Old English usage | wuduælfen, wæterælfen, sǣælfen: "dryads, water-elves, naiads" | Elves are strongly connected to nature. |

| Scandinavian ballad Elvehøj | Mortal visitors to Elfland are in danger, as time seems different there. | Time is distorted in Elfland. |

| Norse mythology | Dökkálfar, Ljósálfar: "light and dark elves" | The Elvish peoples are sundered into multiple groups.[39] |

From words to story

Tolkien devoted enormous effort to placenames, for example making those in The Shire such as Nobottle, Bucklebury, and Tuckborough obviously English in sound and by etymology,[41] whereas the placenames in Bree contain Brittonic (Celtic) language elements.[40] Shippey comments that even though many of these names do not enter the book's plot, they contribute a feeling of reality and depth, giving "Middle-earth that air of solidity and extent both in space and time which its successors [in fantasy literature] so conspicuously lack."[41] Tolkien wrote in one of his letters that his work was "largely an essay in linguistic aesthetic".[T 12]

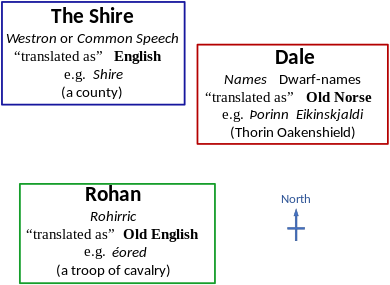

He made use of several European languages, ancient and modern, including Old English for the language of Rohan, Old Norse for the names of Dwarves, and modern English for the Common Speech shared by the peoples of Middle-earth, creating as the story developed a tricky linguistic puzzle. Among other things, Middle-earth was not modern Europe but that region long ages ago, and the Common Speech was not modern English but the imagined ancient language of Westron. Therefore, the dialogue and names written in modern English were, in the fiction, translations from the Westron, and the language and placenames of Rohan were similarly supposedly translated from Rohirric into Old English; therefore, too, the dwarf-names written in Old Norse must have been translated from Khuzdul into Old Norse. Thus the linguistic geography of Middle-earth grew from Tolkien's purely philological or linguistic explorations.[40]

Tolkien's philological liking for lost words expressed itself, too, in his use of what Shippey calls some "strikingly odd words" in The Lord of the Rings. One of these is "dwimmerlaik", from Old English dwimor,[c] which Shippey describes as a hazy concept blending magic and deceit, with "suggest[ions of] veiling, illusion, shape-shifting," and lac, meaning sport or play.[43] Éowyn uses the word to defy the Witch-king of Angmar as they fight to the death in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields: "Begone, foul dwimmerlaik, Lord of carrion!"[43] Shippey reconstructs Tolkien's philological thinking behind his use of the word. He notes that Éowyn's brother Éomer had earlier described Saruman as "a wizard both cunning and dwimmer-crafty, having many guises," giving a gloss on the strange word.[43] Shippey comments that this usefully makes Éomer sound "archaic but not entirely unfamiliar".[43] Another man from Rohan, the traitor Gríma Wormtongue, uses the related word "Dwimordene" for the magical realm of the Elves, glossing it as he speaks with the phrase "webs of deceit were ever woven in Dwimordene."[43] Thus "dwimor/dwimmer" is seen to suggest both magic and deception. Finally, Tolkien uses the name "Dwimorberg", directly translating it into modern English as "the Haunted Mountain".[43] So, Shippey writes, by the time Éowyn shouts "dwimmerlaik", the attentive reader should have been able to pick up the various clues as to its meaning.[43]

| Possible meaning, describing the Witch-king of Angmar |

Origins Old or Middle English |

Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Creature of sorcery | Layamon's Brut speaks of being killed "oðer wid dweomerlace oðer mid steles bite" |

'either with sorcery or with the bite of steel' |

| Sport of nightmare | The 14th century alliterative poem Cleanness mentions "deuinores of demorlaykes þat dremes cowþe rede" |

'diviners of nightmares who tell what dreams mean' |

| Doubtfully real, seemingly non-existent, "as if he too is a creature of deceit and altered vision" |

Old English gedwimer |

'illusion' |

Inventing a tradition of philology

Tolkien described a tradition of philological study of Elvish languages within his legendarium. Elven philologists are indicated by the Quenya term Lambengolmor, "loremasters". In Quenya, lambe means "spoken language" or "verbal communication".[T 13] Tolkien wrote:

The older stages of Quenya were, and doubtless still are, known to the loremasters of the Eldar. It appears from these notices that besides certain ancient songs and compilations of lore that were orally preserved, there existed also some books and many ancient inscriptions.[T 14]

Philologists among the Lambengolmor were Rúmil, who invented the Sarati, the first Elvish script, Fëanor, who developed this script into the Tengwar which became widespread in Middle-earth, and Pengolodh of Gondolin, who wrote the Lhammas or "The Account of Tongues".[T 13]

In The Lord of the Rings, a human philologist appears in the shape of the herb-master of the Houses of Healing in Minas Tirith. The man, asked for the rare herb athelas, displays his learning by reciting its names in different languages, and repeats a rhyme the people used to say about it, but neither has it in store nor sees the need to have it there. Shippey comments that this unsuccessful figure illustrates "in a rather prophetic way" how real knowledge can dwindle until it is no longer felt to be at all useful, as happened to Tolkien's discipline of philology.[44]

The wizard Gandalf, too, has philological leanings. Sherrylyn Branchaw writes in Mythlore that Gandalf twice takes time to study old manuscripts in the hope of gaining knowledge: first in the library at Minas Tirith, where he reads Isildur's crucial account of the One Ring; and again in the darkness of Moria, when he endangers the quest by delaying to read the Book of Mazarbul. She adds that the wizard's struggle with the password written above the Western door to Moria shows both the trap of going too far into philology, and the importance of doing the philology correctly. The inscription could be read as the cryptic "Friend, speak [the unstated password], and enter"; it is only after much delay that Gandalf realises it actually means "Say 'Friend' [Quenya: mellon] and enter", i.e. that the password is stated directly in the plain text, and the learned wizard has overthought the question.[45]

Philological humour

Tolkien stated, in a joking letter that he was surprised to see published in The Observer in 1938, that "the dragon [Smaug] bears as name—a pseudonym—the past tense of the primitive Germanic verb smúgan,[48] to squeeze through a hole: a low philological jest."[T 15] Tolkien scholars have explored what that jest might have been;[46] an 11th-century medical text Lacnunga ("Remedies") contains the Old English phrase wid smeogan wyrme, "against a penetrating [parasitic] worm" in a spell.[d][47] The phrase could also be translated "against a crafty dragon", since the word wyrm meant variously "worm, snake, reptile, dragon",[46][49] while the Old English verb smúgan meant "to examine, to think out, to scrutinise",[50] implying "subtle, crafty". Shippey, like Tolkien a philologist by training, comments that it is "appropriate" that Smaug has "the most sophisticated intelligence" in the book.[46] All the same, Shippey notes, Tolkien has chosen the Old Norse verb smjúga, past tense smaug, rather than the Old English sméogan, past tense smeah—possibly, he suggests, because his enemies were Norse dwarves.[51]

True language, true names

Hey! now! Come hoy now! Whither do you wander?

Up, down, near or far, here, there or yonder?

Sharp-ears, Wise-nose, Swish-tail and Bumpkin,

White-socks my little lad, and old Fatty Lumpkin![Tom Bombadil] reappeared, hat first, over the brow of the hill, and behind him came in an obedient line six ponies: their own five and one more. The last was plainly old Fatty Lumpkin: he was larger, stronger, fatter (and older) than their own ponies. Merry, to whom the others belonged, had not, in fact, given them any such names, but they answered to the new names that Tom had given them for the rest of their lives.[T 16]

Shippey writes that The Lord of the Rings embodies Tolkien's belief that "the word authenticates the thing",[52] or to look at it another way, that "fantasy is not entirely made up."[53] Tolkien, as a professional philologist, had a deep understanding of language and etymology, the origins of words. He found a resonance with the ancient myth of the "true language", "isomorphic with reality": in that language, each word names a thing and each thing has a true name, and using that name gives the speaker power over that thing.[54][55] This is seen directly in the character Tom Bombadil, who can name anything, and that name then becomes that thing's name ever after; Shippey notes that this happens with the names he gives to the hobbits' ponies.[54]

This belief, Shippey states, animated Tolkien's insistence on what he considered to be the ancient, traditional, and genuine forms of words. A modern English word like loaf, deriving directly from Old English hlāf,[56] has its plural form in 'v', "loaves", whereas a newcomer like "proof", not from Old English, rightly has its plural the new way, "proofs".[52] So, Tolkien reasoned, the proper plurals of "dwarf" and "elf" must be "dwarves" and "elves", not as the dictionary and the printers typesetting The Lord of the Rings would have them, "dwarfs" and elfs". The same went for forms like "dwarvish" and "elvish", which he saw as strong and old, and avoiding any hint of dainty little "elfin" flower-fairies, which he saw as weak and recent.[52] Tolkien insisted on the expensive reversion of all such typographical "corrections" at the galley proof stage.[52]

Legacy

Mark Shea, in Jane Chance's 2004 collection of scholarly essays Tolkien on Film, produced soon after Peter Jackson's film trilogy had come to the cinema, wrote a parody of philological scholarship in the form of "a source-critical analysis" of The Lord of the Rings tradition in print and on film.[57] The analysis states that "Experts in source-criticism now know that The Lord of the Rings is a redaction of sources ranging from The Red Book of Westmarch (W) to Elvish Chronicles (E) to Gondorian records (G) to orally transmitted tales of the Rohirrim (R)," each with "their own agendas", like "the 'Tolkien' (T) and 'Peter Jackson' (PJ) redactors". It states confidently that "we may be quite certain that 'Tolkien' (if he ever existed) did not write this work in the conventional sense, but that it was assembled over a long period of time..." and that "T is heavily dependent on G records and clearly elevates the claims of the Aragorn monarchy over the House of Denethor." It comments that "Of course, the 'Ring' motif appears in countless folk tales and is to be discounted altogether", while "the 'Gandalf' narratives" seem to be shamanistic legends, recorded in W "out of deference to local Shire cultic practice."

Notes

- ^ In turn, Fauflor was from Old English fāg flōr.[18][19]

- ^ In drafts of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien toyed with names such as Harwan and Sunharrowland for Harad; Christopher Tolkien notes that these are connected to his father's Sigelwara Land.[T 6]

- ^ Clark Hall defines this as "phantom, ghost, illusion, error".[42]

- ^ Storms translates the spell: "If a man or a beast has drunk a worm ... Sing this charm nine times into the ear, and once an Our Father. The same charm may be sung against a penetrating worm. Sing it frequently on the wound and smear on your spittle, and take green centaury, pound it, apply it to the wound and bathe with hot cow's urine." The Old English source is MS. Harley 585, ff. 136b, 137a (11th century) (Lacnunga).[47]

References

Primary

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #165 to Houghton Mifflin, 30 June 1955

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1926, p. 64

- ^ Tolkien 2014, p. 33

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 6 "The King of the Golden Hall"

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1932; Tolkien 1934

- ^ a b Tolkien 1989, ch. 25 p. 435, and p. 439 note 4 (comments by Christopher Tolkien)

- ^ Tolkien 1932b

- ^ a b Tolkien 1994, "Quendi and Eldar"

- ^ Tolkien 1983, pp. 198–223

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, Foreword to the Second Edition

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman (at Collins), late 1951

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #165 to Houghton Mifflin, June 1955

- ^ a b Tolkien 1987, "The Lhammas"

- ^ Tolkien 2010, p. 68

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #25 to the editor of The Observer, 16 January 1938

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 8, "Fog on the Barrow-downs"

Secondary

- ^ a b c d Anger 2013, pp. 563–564

- ^ Garth 2003, p. 16.

- ^ a b Flieger 1983, p. 5.

- ^ a b Flieger 1983, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #297, draft, to Mr Rang, August 1967

- ^ a b c Lee & Solopova 2005, p. 256.

- ^ a b Garth 2003, p. 44.

- ^ a b Carpenter 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Solopova 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Carpenter 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Tolkien 1984b, pp. 266–269

- ^ Tolkien 1984b, p. 266

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 66–74.

- ^ a b Shippey 2001, p. 88.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Shippey 2001, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Shippey 2001, pp. 90–97.

- ^ Mills 1993, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Shippey 2005, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b c Fimi 2016

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, pp. 49, 54, 63.

- ^ Flieger 1983, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Vanderbilt 2020.

- ^ Armstrong 1997, pp. 13–14.

- ^ BBC 2014.

- ^ Bowers 2019, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Rateliff 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Smith 2013, pp. 600–601.

- ^ a b c Hostetter 2006.

- ^ Flieger 1983, pp. 88–131.

- ^ Kalevala Society 2016.

- ^ Chance 1980, Title page and passim.

- ^ Jackson 2015, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e Kuusela 2014, pp. 25–36.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 282–284.

- ^ a b c Shippey 2005, pp. 129–133.

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Clark Hall 2002, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shippey 2006, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Shippey 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Branchaw 2015.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 102–104.

- ^ a b c Storms 1948, p. 303.

- ^ Bosworth & Toller 2018, smúgan.

- ^ Clark Hall 2002, p. 427.

- ^ Clark Hall 2002, p. 311.

- ^ Shippey 2002.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 63–66.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, pp. 115, 121.

- ^ Zimmer 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Clark Hall 2002, p. 185.

- ^ Shea 2004, pp. 309–311.

Sources

- Anger, Don N. (2013) [2007]. "Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 563–564. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Armstrong, Helen (May 1997). "And Have an Eye to That Dwarf". Amon Hen: The Bulletin of the Tolkien Society (145): 13–14.

- BBC (24 September 2014). "Tolkien's tales from Lydney Park". BBC. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- Bosworth, Joseph; Toller, T. Northcote (2018). "smúgan". An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Prague: Charles University.

- Branchaw, Sherrylyn (2015). "Tolkien's Philological Philosophy in His Fiction". Mythlore. 34 (1). Article 5, pp. 37–50.

- Bowers, John M. (2019). Tolkien's Lost Chaucer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884267-5.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0618057023.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Chance, Jane (1980) [1979]. Tolkien's Art: 'A Mythology for England'. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-29034-7.

- Clark Hall, J. R. (2002) [1894]. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Exodus author. "Junius 11 "Exodus" ll. 68-88". The Medieval & Classical Literature Library. Retrieved 1 February 2020.</ref>

- Fimi, Dimitra (September 2016). Tolkien and the Art of Book Reviewing: A Circuitous Road to Middle-earth. Oxonmoot.

- Flieger, Verlyn (1983). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World. Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-1955-0.

- Garth, John (2003). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00711-953-0.

- Hostetter, Carl F. (2006). "Elvish as She is Spoke". In Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (eds.). The Lord of the Rings 1954-2004: Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder. Marquette University Press. ISBN 978-0-87462-018-4.

- Jackson, Aaron Isaac (2015). Narrating England: Tolkien, the Twentieth Century, and English Cultural Self-Representation (PDF). Manchester Metropolitan University (PhD thesis).

- Kalevala Society (2016). "Elias Lönnrot". The Kalevala Society. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Kuusela, Tommy (May 2014). "In Search of a National Epic: The use of Old Norse myths in Tolkien's vision of Middle-earth". Approaching Religion. 4 (1): 25–36. doi:10.30664/ar.67534.

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1403946713.

- Mills, A. D. (1993) [1991]. A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283131-6.

- Rateliff, John D. (2006). "'And All the Days of Her Life Are Forgotten': 'The Lord of the Rings' as Mythic Prehistory". In Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (eds.). The Lord of the Rings, 1954-2004: Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder. Marquette University Press. pp. 67–100. ISBN 0-87462-018-X. OCLC 298788493.

- Shea, Mark (2004). "The Lord of the Rings: A Source-Critical Analysis". In Croft, Janet Brennan (ed.). Tolkien on Film: Essays on Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings. Mythopoeic Press. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-1-887726-09-2.

- Shippey, Tom (2001) [2000]. J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Shippey, Tom (13 September 2002). "Tolkien and Iceland: The Philology of Envy". Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

- Shippey, Tom (2006). "History in Words: Tolkien's Ruling Passion". In Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (eds.). The Lord of the Rings, 1954-2004: Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder. Marquette University Press. pp. 25–40. ISBN 0-87462-018-X. OCLC 298788493.

- Smith, Arden R. (2013) [2007]. "Secret Vice, A". J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 600–601. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Solopova, Elizabeth (2009). Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J. R. R. Tolkien's Fiction. New York City: North Landing Books. ISBN 978-0-9816607-1-4.

- Storms, Godfrid (1948). No. 73. [Wið Wyrme] Anglo-Saxon Magic (PDF). 's-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff; D.Litt thesis for University of Nijmegen. p. 303.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1926). "[Review]: Introduction to the Survey of Place-Names". The Year's Work in English Studies (5): 64.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (December 1932). "Sigelwara Land part 1". Medium Aevum. 1 (3). JSTOR 43625831.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (June 1934). "Sigelwara Land part 2". Medium Aevum. 3 (2). JSTOR 43625895.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1932b). "'The Name Nodens', Appendix to Report on the excavation of the prehistoric, Roman and post-Roman site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire". Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London.; also in Tolkien Studies: An Annual Scholarly Review, Vol. 4, 2007.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983). "A Secret Vice". The Monsters and the Critics. George Allen & Unwin. pp. 198–223. ISBN 978-0-2611-0263-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984b). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36614-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1989). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Treason of Isengard. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-51562-4.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (2010). "Outline of Phonology". Parma Eldalamberon (19): 68.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2014). Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-759006-3.

- Vanderbilt, Scott (2020). "RIB 306. Curse upon Senicianus". Roman Inscriptions of Britain website. Retrieved 17 February 2020. funded by the European Research Council via the LatinNow project

- Zimmer, Mary (2004). "Creating and Re-creating Worlds with Words". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the invention of myth: a Reader. University Press of Kentucky. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8131-2301-1.

![Ēala ēarendel engla beorhtast / ofer middangeard monnum sended, "Hail Earendel, brightest of angels, over Middle-earth to men sent" (second half of top line, first half of second line) - part of the poem Crist 1 in the Exeter Book, folio 9v, top[5]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Eala_Earendel_engla_beorhtast_-_Exeter_Book_folio_9v_top_two_lines.jpg/450px-Eala_Earendel_engla_beorhtast_-_Exeter_Book_folio_9v_top_two_lines.jpg)