Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

-

(Top)

-

1 Definition of services

-

2 Comparison of manufacturing and services

-

3 Service industries

-

4 Service design

-

5 Operations decisions

-

6 References

-

7 Further reading

| Business administration |

|---|

| Management of a business |

Operations management for services has the functional responsibility for producing the services of an organization and providing them directly to its customers.[1]: 6–7 It specifically deals with decisions required by operations managers for simultaneous production and consumption of an intangible product. These decisions concern the process, people, information and the system that produces and delivers the service. It differs from operations management in general, since the processes of service organizations differ from those of manufacturing organizations.[2]: 2–7

In a post-industrial economy, service firms provide most of the GDP and employment. As a result, management of service operations within these service firms is essential for the economy.[3]

The services sector treats services as intangible products, service as a customer experience and service as a package of facilitating goods and services. Significant aspects of service as a product are a basis for guiding decisions made by service operations managers.[4] The extent and variety of services industries in which operations managers make decisions provides the context for decision making.

The six types of decisions made by operations managers in service organizations are: process, quality management, capacity & scheduling, inventory, service supply chain and information technology.[5]

Definition of services

There have been many different definitions of service. Russell and Taylor (2011) state that one of the most pervasive, and earliest definitions is “services are intangible products”.[6] According to this definition, service is something that cannot be manufactured. It can be added after manufacturing (e.g. product repair) or it can stand alone as a service (e.g. dentistry) delivered directly to the customer. This definition has been expanded to include such ideas as “service is a customer experience.”[7]: 7–8, 162–192 [8] In this case the customer is brought into the definition as the experience the customer receives while “consuming” the service.

A third definition of service concerns the perceived service as consisting of physical facilitating goods, explicit service and implicit service.[6] In this case the facilitating goods are the buildings and inventory used to provide the service. For example, in a restaurant the facilitating goods are the building and the food. The explicit service is what is perceived as the observable part of the service (the sights, sounds and look of the service). In a restaurant the explicit service is the time spent waiting for service, the appearance of the facility and the employees, and the ambience of sounds and light and the decor. The implicit service is the feeling of safety, psychological well-being and happiness associated with the service.

Comparison of manufacturing and services

According to Fitzsimmons, Fitzsimmons and Bordoloi (2014) differences between manufactured goods and services are as follows:[4]: 14–18

- Simultaneous production and consumption. High contact services (e.g. haircuts) must be produced in the presence of the customer, since they are consumed as produced. As a result, services cannot be produced in one location and transported to another, like goods. Service operations are therefore highly dispersed geographically close to the customers. Furthermore, simultaneous production and consumption allows the possibility of self-service involving the customer at the point of consumption (e.g. gas stations). Only low-contact services produced in the "backroom" (e.g., check clearing) can be provided away from the customer.

- Perishable. Since services are perishable, they cannot be stored for later use. In manufacturing companies, inventory can be used to buffer supply and demand. Since buffering is not possible in services, highly variable demand must be met by operations or demand modified to meet supply.

- Ownership. In manufacturing, ownership is transferred to the customer. Ownership is not transferred for service. As a result, services cannot be owned or resold.

- Tangibility. A service is intangible making it difficult for a customer to evaluate the service in advance. In the case of a good, customers can see it and evaluate it. Assurance of quality service is often done by licensing, government regulation, and branding to assure customers they will receive a quality service.

These four comparisons indicate how management of service operations are quite different from manufacturing regarding such issues as capacity requirements (highly variable), quality assurance (hard to quantify), location of facilities (dispersed), and interaction with the customer during delivery of the service (product and process design).

Service industries

Industries have been defined by economists as consisting of four parts: Agriculture, Mining and Construction, Manufacturing, and Service.[9] Services have existed for centuries. Early service was associated with servants. Servants were hired to do tasks that the wealthy did not want to do for themselves (e.g. cleaning the house, cooking, and washing clothes). Later, services became more organized and were provided to the general public.

In 1900 the U.S. service industry (e.g., consisting of banks, professional services, schools and general stores) was fragmented, except for the railroads and communications. Services were largely local in nature and owned by entrepreneurs and families. The U.S. in 1900 had 31% employment in services, 31% in manufacturing and 38% in agriculture.[10]

Services have now evolved to become the dominant form of employment in industrialized economies. Much of the world has progressed, or is progressing, from agricultural to industrial and now post-industrial economies.[3] The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a table of the employment of the 151 million people by industry in the U.S. for 2014.

| Industry | % employment |

|---|---|

| Agriculture and Mining | 2 |

| Construction | 5 |

| Manufacturing | 10 |

| Federal Government | 2 |

| State Governments | 13 |

| Leisure & Hospitality | 9 |

| Health Care and Social | 10 |

| Education Private | 2 |

| Professional and Business | 11 |

| Financial Services | 6 |

| Information Services | 2 |

| Transportation & Utilities | 3 |

| Retail and Wholesale | 14 |

| Other services | 4 |

| Self Employed | 7 |

| Totals | 100 |

Source:[9]

The table shows that service industries now constitute 83% of employment in the U.S., while agriculture, mining, construction and manufacturing are only 17% of the total employment. Service industries are very diversified ranging from those that are highly capital intensive (e.g. banks, utilities, airlines, and hospitals) to those that are highly people intensive (e.g. retail, wholesale, and professional services). In capital intensive services the focus is more on technology and automation, while in people intensive services the focus is more on managing service employees that deliver the service.[6]

Service and manufacturing industries are highly interrelated. Manufacturing provides tangible facilitating goods needed to provide services; and services such as banking, accounting and information systems provide important service inputs to manufacturing. Manufacturing companies have an opportunity to provide more services along with their products. This can be an important point of product differentiation, leading to increased sales and profitability for manufacturers.[2]: 2–7

While the focus is often on service industries, there is an opportunity to apply service principles to internal services in an organization, particularly by focusing on internal customers. Internal services such as payroll, accounting, legal, information systems or human resources often have not identified their internal customers, nor do they understand their customer needs. Service ideas ranging from process design, to lean systems, quality management, capacity and scheduling have been widely applied to internal services.[11][7]: 30–32

Service design

Service design begins with a business strategy and service strategy. The business strategy defines what business the firm is in, for example, the Walt Disney Company defines its business strategy "as making people happy." A business strategy also defines the target market, competitors, financial goals, new products, how the company competes, and perhaps some aspects of operations.

Following from the business strategy is the service concept.[7]: 47–50 It must provide the rationale for why the customer should buy the service offered. It defines what the customer is receiving and what the service organization is providing. The service concept includes:

- Organizing Idea. The vision and essence of the service.

- Service Provided. The process and results designed by the provider.

- Service Received. The customer experience and outcomes expected.

Managers can use the service concept to create organizational alignment and develop new services. It provides a means for describing the service business from an operations point of view.

After defining the service concept, operations can proceed to define the service-product bundle (or service package) for the organization. It consists of five parts: service facility, facilitating goods, information, explicit service and implicit services.[4] It is important to carefully define each of these elements so that operations can subsequently design and manage a service operation. The service-product bundle must come first before operations decisions.

An example of service-product bundle characteristics follows:[4]: 18–19

- Service Facility: Accessible by public transportation, sufficient parking, interior decorating, architecture, facility layout and traffic flow

- Facilitating goods: sufficient inventory, quality and selection

- Information: Is it accurate, up-to-date, timely, and useful to the customer and service providers

- Explicit service: waiting time, training and appearance of personnel, and consistency

- Implicit service: Sense of well-being, privacy and security, atmosphere, attitude of service providers.

Once the service package is specified, operations is ready to make decisions concerning the process, quality, capacity, inventory, supply chain and information systems. These are the six decision responsibilities of service operations. Other decision responsibilities such as market choice, product positioning, pricing, advertising and channels belong to the marketing function. Finance takes care of financial reporting, investments, capitalization, and profitability.

Operations decisions

Process decisions

Process decisions include the physical processes and the people that deliver the services to the customer. A service process consists of all the routines, tasks and steps that are used to deliver service to customers along with the jobs and training for service employees. There are many ways to organize a process to provide customer service in an effective and efficient manner to deliver the service-product bundle. Several ideas have been advanced on how to design a service process.[12]: 173–243, 401–431

Customer contact

Design of a service system must consider the degree of customer contact. The importance of customer contact was first noted by Chase and Tansik (1983).[13] They argued that high customer contact processes should be designed and managed differently from low-contact processes. High-contact processes have the customer in the system while providing the service. This can lead to difficulties in standardizing the service or inefficiencies when the customer makes demands or expects unique services. On the other hand, high-contact also provides the possibility of self-service where customers provide part of the service themselves (e.g. filing your own gas tank, or packing your own groceries). Low-contact services are performed away from the customer in what is often called "the back room." In this case, the service process can be more standardized and efficient (e.g. check clearing in a bank, filling orders in a warehouse) since the customer is not in the system to request preferences, customization or changes. Low-contact services can be managed more like manufacturing, high-contact services cannot.

Production-line approach

In 1972 Levitt introduced the "production-line approach to service".[14] He argued that service processes could be made more efficient by standardizing them and automating them like manufacturing. He gave the example of McDonald's that has standardized both the services at the front counter and the backroom for producing the food. They have limited the menu, simplified the jobs, trained the managers (at "Hamburger U"), automated production and instituted standards for courtesy, cleanliness, speed and quality. As a result, McDonald's has become a model for other service processes which have been designed for high efficiency, not only in fast food, but in many other services. At the same time, it leaves open the option for more customized and flexible services for customers who are willing to pay more for "better" or more personalized service. While these services are less efficient, they cater more to unique customer's needs.

Service process matrices

Many different service process matrices have been proposed for explaining the relationship between service products that are selected and corresponding processes.[7]: 193–225 One of these is shown below.

The Service Delivery System Matrix[15] by Collier and Meyer (1998) illustrates the various types of routings used for service process depending on the amount of customization and customer involvement in the process. With high levels of customization and customer involvement, there are many pathways and jumbled flows for service. As a result, the service delivery of Customer-Routed services is less efficient than Co-routed or Provider-Routed processes that have less customization and less customer involvement. Process that should be used for each combination of customization and customer involvement are shown on the diagonal of this matrix.

Self-service

Self-service is in wide use. For example, in the 1960s gas station attendants came out and pumped your gas, cleaned your windshield and even checked your oil. Fast food is famous for self-service, since customers have been trained to order their own food, pay immediately, find a table, and clean up the trash. ATM's have replaced many traditional tellers and online banking provides even more self-service.

When self-service is accepted by the customer, it can reduce costs and even provide better service in the customer's eyes—faster service with less hassle.[12]: 173–243, 401–431 Self-service falls in the provider-routed or co-routed part of the Service delivery matrix. Services that were previously customer-routed have been moved down the diagonal to be more efficient and accepted by customers.

Service Blueprint The service blueprint is a way to describe the flow of a customer through a service operation from the start to the finish, along with the actions provided by the service providers both in interaction with the customer and in the "back room" out of sight of the customer. For example, if a customer wishes to purchase a suit, the service blueprint starts with entry to the store, next the customer is greeted by a sales representative, the customer then provides information on his/her needs, the sales representative searches for appropriate suits, one or more suits are selected and tried-on for a fitting, a suit is selected and then alterations are done (which take place away from the customer), the customer pays for the suit and returns later to pick it up. A blueprint flowchart shows every step in the process and can be used to illustrate the process and improve it.[16]

Lean thinking

If lean thinking is applied, the time taken for each step in a service blueprint flowchart can be recorded, or a separate value-stream map can be constructed. Then the process can be analyzed for time reductions to reduce waiting and non-value added steps.[11] Changes are made to reduce time and waste in the process. Waste is anything that does not add value to the process including waiting time in line, possibility of more self-service, customer hassle, and defects in service. But, lean thinking also requires attention to the customer and the people providing the service. It is important to apply important principles such as completely solve the customer's problem, don't waste time and provide exactly what the customer requires.

Leite and Vieira (2015) state that service managers must realize that the customer will be happy if the service provided meets or exceeds expectations. Also the interaction between the customer and the people providing the service is essential to achieve satisfied customers. Employee involvement is often emphasized as part of lean thinking to achieve high levels of commitment by service employees.[17]

Queuing

Queuing is an analytic method for determining waiting time when customers must wait in line to get service. The length of the queue and waiting time can be calculated based on the arrival rate, service rate, number of servers and type of lines. There are many formulas for various types of queuing theory problems.[18] The formulas generally predict that the average service time must be significantly less than the average time between arrivals when there is randomness in arrivals and/or service time. The reason for this is that a long line will build up when randomness of arrivals occurs faster than the average and service times are longer than the average. If the distributions of arrival times and service times are known, formulas are available for calculating the exact waiting times and line lengths for many different queuing configurations of servers, types of lines, server distributions and arrival distributions.

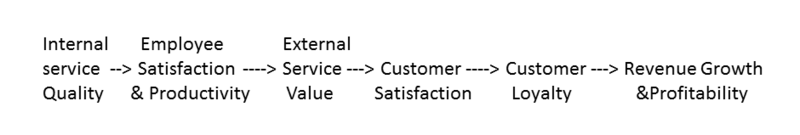

Service-profit chain

Heskett, Sasser and Schlensinger (1997) proposed the service-profit chain as a way to design service processes. The service-profit chain links various aspects and tasks required to deliver superior service and profits. It starts with a high level of internal quality leading to employee satisfaction and productivity to deliver superior external customer service leading to customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and finally high revenues and profits.[19]

Every link in this chain is important and the linkage between the service providers and the customer is essential in service operations. The service manager should not break any of the links in order to receive the results of high probability and growth.

Quality management

SERVQUAL measurement

Using the customer experience approach, a questionnaire called SERVQUAL has been developed to measure the customer's perception of the service.[20] The dimensions of SERVQUAL are designed to measure the customer experience in both explicit and implicit measures. The dimensions are:

- Tangible: Cleanliness, appearance of facilities and employees

- Reliability: Accurate, dependable and consistent services without errors

- Responsiveness: Promptly assist customers in a timely manner

- Assurance: Conveying knowledge, trust and confidence

- Empathy: Caring, approach-ability and relating to customers

A debate about SERVQUAL has ensued about whether customer service should be measured in absolute terms or relative to expectations.[21] Some argue that if high levels on all SERVQUAL dimensions are provided then the service is high quality. Others argue that ultimately the service result is judged by the customer relative to the customer's expectations and not by the service provider. If customer expectations are low, even low levels on SERVQUAL dimensions provides high quality.

Quality management approaches

Quality management practices for services have much in common with manufacturing, despite the fact that the product is intangible. The following approaches are widely used for quality improvement in both manufacturing and services:

- The Baldrige Awards: A comprehensive framework for quality improvement in organizations[22]

- The W. Edwards Deming Management Method: Fourteen Points for Management[23]

- Joseph Juran's Approach: Planning, Improvement and Control[24][25]

- Six Sigma: DMAIC (Design, Measurement, Analysis, Improvement and Control)[26][27]

These approaches have several things in common. They begin with defining and measuring the customer's needs (e.g. using SERVQUAL). Any service that does not meet a customer's need is considered a defect. Then these approaches seek to reduce defects through statistical methods, cause-and-effect analysis, problem solving teams, and involvement of employees. They focus on improving the processes that underlie production of the service.[28]

In addition to intangibility, there are two approaches about quality that are unique to service operations management.

Service recovery

For manufactured products, quality problems are handled through warranties, returns and repair after the product is delivered. In high contact services there is no time to fix quality problems later; they must be handled by service recovery as the service is delivered. For example, if soup is spilled on the customer in a restaurant, the waiter might apologize, offer to pay to have the suit cleaned and provide a free meal. If a hotel room is not ready when promised, the staff could apologize, offer to store the customer's luggage or provide an upgraded room. Service recovery is intended to fix the problem on the spot and go even further to offer the customer some form of consolation and compensation. The objective is to make the customer satisfied with the situation, even though there was a service failure.[29][30]

Service guarantee

A service guarantee is similar to a manufacturing guarantee, except the service product cannot be returned. A service guarantee provides a specific monetary reward for failure of service delivery. Some examples are:

- Your package will be delivered by the time promised or you will not pay.

- We will fix your automobile or give you $100 if you must bring it back for repair.

- Customers that are not satisfied with their haircut, get the next haircut free.

Service guarantees serve to assure the customer of quality and they provide a way for the employees to know the cost of service failure.[31][32]

Capacity and scheduling

Forecasting

Forecasting demand is a prerequisite for managing capacity and scheduling. Forecasting demand often uses big data to predict customer behavior. The data comes from scanners at retail locations or other service locations. In some cases traditional time series methods are also used to predict trends and seasonality. Future demand is forecasted based on past demand patterns. Many of the same time-series and statistical methods for forecasting are used for manufacturing or service operations.[33][34]

Capacity planning

Capacity planning is quite different between manufacturing and services given that service cannot be stored or shipped to another location.[1]: 208–241 As a result, location of services is very dispersed to be near the customer. Customers are only willing to travel short distances to receive most services. Exceptions are health care when the illness requires a specialist, airline transportation when the service is to move the customer, and other services where local expertise is not available. Aside from these exceptions, location analysis depends on the "drawing power" based on the distance a customer is willing to travel to a service site relative to competitive offerings and locations. The drawing power of a site for a particular customer is high if the site is close by and provides the required service. High drawing power is related to high sales and profits. This is very different from manufacturing locations which depend on the cost of building a factory plus the cost of transporting the goods to the customers. Manufacturing plants are located on the basis of low costs rather than high revenues and profits for services.

A second difference from manufacturing is planning for capacity utilization once a facility is built. Since the product cannot be stored in inventory and sold later, service capacity is perishable and must meet peak demand at any point in time.[12]: 96–129 There are two ways to deal with this problem. First, management can attempt to reduce peak demand and level it over time by the following actions.

- Higher prices during peak-demand times

- A reservation system to limit peak demand

- Advertising and promotion to shift peak demand

Management can also use various methods to manage the supply of services including:

- Part-time labor

- Hiring and Layoff of Employees

- Using Overtime

- Subcontracting

While some of these same mechanisms are used in manufacturing, they are much more crucial in service operations.

Revenue management

Revenue management is unique to services, since capacity is perishable. This applies to the airline industry. When the plane leaves the runway, empty seats generate no revenue, but the cost of the flight is almost the same. As a result, mathematical models have been formulated to allocate capacity at various prices and times as the flight is booked in advance. Initially, a certain number of seats are reserved for first class, coach, premium coach and various other categories. Based on the elasticity of demand, seats prices are lowered at the last minute in order to fill empty seats and maximize the revenue of the flight.[35] Similar models have also been developed for revenue management in hotels, where the capacity is also perishable.[36]

Scheduling

Scheduling has some differences between manufacturing and service. In manufacturing, jobs are scheduled through a factory to sequence them in the best order to meet due dates and reduce costs. In services, it is customers who are being scheduled. As a result, waiting time becomes much more critical. While manufacturing orders don't mind waiting in line or waiting in inventory, real customer's do mind. Some of the scheduling applications for services are: scheduling of patients to operating rooms in hospitals and scheduling students to classes. Many scheduling problems have been solved by using operations research methods to optimize the schedule.[37]

Inventory

Inventory management and control is needed in service operations with facilitating goods. Almost every service uses some amount of facilitating goods. The presence of facilitating goods is critical in retail and wholesale operations but these operations don't manufacture anything, rather they distribute goods and provide service while doing it. One difference from manufacturing inventories is that services use only finished goods, while manufacturing has finished goods, work-in-process and raw-materials inventories. As a result, manufacturing uses a Materials Requirements Planning System, while services do not. Services use Replenishment inventory control systems such as order-point and periodic-review systems.[38]

Service supply chains

Supply chains for service operations are critical to supply facilitating goods. A typical hospital supply chain is an example. A hospital will use many goods from suppliers to construct and furnish the building. During day-to-day operation of the hospital, inventories of supplies will be held for the operating rooms and throughout the building. The pharmacy will hold drugs and the kitchen will need supplies of food. The supply chain of facilitating goods in hospitals is extensive.

Purchasing controls a large part of costs in retail and wholesale operations, approximately 75% of all costs are for purchased goods. Outside of retail and wholesale operations, facilitating goods are a much smaller part of total costs reaching a low of 10% for most professional services.[1]: 291–334 Both manufacturing and service organizations purchase goods and must deal with outsourcing and offshoring, as well as, domestic products.

Service inputs are critical for manufacturing including capital from banks, energy, information systems and human resources. Services are part of the manufacturing supply chain, just like the physical inputs of products from other manufacturing companies.

Both manufacturing and service operations can purchase services from outside the organization. Internal business services such as accounting, legal, human resources, call centers, and information systems may be outsourced in part or entirely. Some of these services can also be purchased from offshore. Logistics services may be outsourced to Third Party Logistics (3PL) providers. These services include transportation, warehousing, order fulfillment, returns and tariffs.[7]: 31–32

Information technology

The Internet and information technology has dramatically changed the delivery of services. Some of the major changes are as follows:[4]

- Providing information and knowledge directly to consumers. Before the Internet, consumers used a variety of sources for acquiring knowledge including libraries, phone calls, universities and personal contacts. Now information can be provided immediately as a service by searching the Internet.

- Providing service at a distance. Services such as call centers, banking, entertainment and legal services can be provided over long distances, even internationally.

- Reservations can be made on the Internet to reserve capacity more easily than by calling ahead for the reservation.

- Facilitating goods can be ordered directly by the Internet and delivered without traveling to a retail store. The services provided includes browsing for merchandise, order entry, order checking, payment, order confirmation, notification of delivery and return services.

- Internal information systems now provide an array of management information to help managers make better decisions.

Management science and operations research (MSOR)

Analysis using MSOR methods has been extensive in services. Areas where they have been heavily applied are in inventory, capacity, scheduling, queuing and forecasting. With the advent of the Internet, information systems, big data and analytics, there are many opportunities to make improvements in decision making for services. The analytic techniques include statistics, management science[39] and operations research.[40]

References

- ^ a b c Bozarth, Cecil and Handfield, Robert (2006). Introduction to Operations and Supply Chain Management. Upper Saddle River, N.J., Pearson. ISBN 0-13-185804-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Malhotra, Manoj K.; Krajewski, Lee J.; Ritzman, Larry P. (2013). Operations management : processes and supply chains (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-280739-5.

- ^ a b Bell, Daniel (1973). The coming of post-industrial society; a venture in social forecasting. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465012817.

- ^ a b c d e Fitzsimmons, James; Fitzsimmons, Mona; Bordoloi, Sanjeev (2014). Service Management: Operations, Strategy, Information Technology, 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-0-07-802407-8.

- ^ Heizer, Jay; Render, Barry (2011). Operations Management, 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-13-611941-8.

- ^ a b c Russell, Roberta; Taylor, Bernard (2011). Operations Management: Creating Value Along the Supply Chain, 7th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-470-52590-6.

- ^ a b c d e Johnston, Robert; Clark, Graham; Shulver, Michael (2012). Service Operations Management: Improving Service Delivery (Fourth ed.). London, England: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-273-74048-3.

- ^ Meyer, Christopher; Schwager, Andre (February 2007). "Understanding Customer Experience". Harvard Business Review. 85 (2): 116–26, 157. PMID 17345685.

- ^ a b Richard Henderson (2015). "Industry employment and output projections to 2024 : Monthly Labor Review". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- ^ Fisk, Donald M. (2003-01-30). "American Labor in the Twentieth Century" (PDF). www.bls.gov. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- ^ a b Womack, J.P. and Jones, D.T. (2003). Lean Thinking. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-4927-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Jacobs F. Robert and Chase, Richard B. (2013). Operations and supply chain management: The Core, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-0-07-352523-5.

- ^ Chase, Richard; Tansik, David (1983). "The Customer Contact Model for Organizational Design". Management Science. 29 (9): 1037–1050. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.9.1037.

- ^ Levitt, Theodore (1972). "The Production-Line Approach to Service". Harvard Business Review. 50 (4): 41–52. OCLC 45573321.

- ^ Collier, David; Meyer, Susan (1998). "A Service Positioning Matrix". International Journal of Operations & Production Management. 18 (2): 1223–1244. doi:10.1108/01443579810236647.

- ^ Shostack, Lynn (1984). "Designing Services that Deliver". Harvard Business Review. 62 (1): 133–139.

- ^ Leite, Higor dos Reis; Vieira, Guilherme Ernani (September 2015). "Lean philosophy and its applications in the service industry: a review of the current knowledge". Production. 25 (3): 529–541. doi:10.1590/0103-6513.079012.

- ^ Gross, Donald (1974). Fundamentals of queueing theory. New York: Wiley. ISBN 047132812X.

- ^ Schlesinger, James L. Heskett; W. Earl Sasser; Leonard A. (1997). The service profit chain : how leading companies link profit and growth to loyalty, satisfaction, and value. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 978-0684832562.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berry, Valarie A. Zeithaml, A. Parasuraman, Leonard L. (1990). Delivering quality service : balancing customer perceptions and expectations. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780029357019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nyeck, Simon; Morales, Miguel; Ladhari, Riadh; Pons, Frank (December 2002). "10 years of service quality measurement: reviewing the use of the SERVQUAL instrument". Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science. 7 (13).

- ^ "Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA)". ASQ. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- ^ Deming, W. Edwards (1986). Out of the Crisis. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262541152.

- ^ Juran, Joseph M. and DeFeo, Joseph A. (2010). Juran's Quality Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071629737.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Juran, Joseph M. (2004). Architect of Quality: The Autobiography of Dr. Joseph M. Juran. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071589789.

- ^ Tennant, Geoff (2001). Six Sigma: SPC and TQM in Manufacturing and Services. Grover Publishing, Ltc. ISBN 9780566083747.

- ^ Breyfogle, Forrest W. III (1999). Implementing Six Sigma: Smarter Solutions Using Statistical Methods. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471265726.

- ^ Harvey, J (1998). "Service quality: a tutorial". Journal of Operations Management. 16 (5): 583–597. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(97)00026-0. ISSN 0272-6963.

- ^ Hart, Christopher; Heskett, James; Sasser, W. Earl Jr. (1990). "The Profitable Art of Service Recovery". Harvard Business Review. 68 (4): 148–56. PMID 10106796.

- ^ Maxham, James G. III (October 2001). "Service Recovery's Influence on Consumer Satisfaction, Word-of-Mouth and Purchase Intentions". Journal of Business Research. 54: 11–24. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00114-4.

- ^ Hart, Christopher W.L. (July 1988). "The Power of Unconditional Service Guarantees". Harvard Business Review: 54–62.

- ^ Baker, Tim; Collier, David (2005). "The Economic Payout Model for Service Guarantees". Decision Sciences. 36 (2): 197–220. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5414.2005.00071.x.

- ^ Armstrong, Scott, ed. (2001). Principles of Forecasting: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-0792374015.

- ^ Gilchrist, Warren (1976). Statistical Forecasting. London: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471994022.

- ^ Talluri, K; van Ryzin, G (1999). "Revenue Management: Research Overview and Prospects" (PDF). Transportation Science. 33 (2): 233–256. doi:10.1287/trsc.33.2.233.

- ^ Cross, R. (1997). Revenue Management: Hard-Core Tactics for Market Domination. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0767900331.

- ^ Pinedo, Michael (2009). Planning and Scheduling in Manufacturing and Services (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-0909-1.

- ^ Muller, Max (2011). Essential of Inventory Management (2nd ed.). AMACOM. ISBN 978-0814416556.

- ^ Thompson, Gerald E. (1982). Management Science: An Introduction to Modern Quantitative Analysis and Decision Making. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070643604.

- ^ Hiller, Frederick; Lieberman, Gerald (2014). Introduction to Operations Research (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0077298340.

Further reading

- Chase, Richard B.; Apte, Uday M. (March 2007). "A history of research in service operations: What's the big idea?". Journal of Operations Management. 25 (2): 375–386. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2006.11.002.

- Sprague, Linda G. (March 2007). "Evolution of the field of operations management". Journal of Operations Management. 25 (2): 219–238. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2007.01.001.

- Chase, Richard B. (November 1978). "Where Does the Customer Fit in a Service Operation?". Harvard Business Review. 56 (6).