Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysics, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed.[1]

The term observatoire has been used in French since at least 1976 to denote any institution that compiles and presents data on a particular subject (such as public health observatory) or for a particular geographic area (European Audiovisual Observatory).

Astronomical observatories

Astronomical observatories are mainly divided into four categories: space-based, airborne, ground-based, and underground-based. Historically, ground-based observatories were as simple as containing an astronomical sextant (for measuring the distance between stars) or Stonehenge (which has some alignments on astronomical phenomena).

Ground-based observatories

Ground-based observatories, located on the surface of Earth, are used to make observations in the radio and visible light portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Most optical telescopes are housed within a dome or similar structure, to protect the delicate instruments from the elements. Telescope domes have a slit or other opening in the roof that can be opened during observing, and closed when the telescope is not in use. In most cases, the entire upper portion of the telescope dome can be rotated to allow the instrument to observe different sections of the night sky. Radio telescopes usually do not have domes.[citation needed]

For optical telescopes, most ground-based observatories are located far from major centers of population, to avoid the effects of light pollution. The ideal locations for modern observatories are sites that have dark skies, a large percentage of clear nights per year, dry air, and are at high elevations. At high elevations, the Earth's atmosphere is thinner, thereby minimizing the effects of atmospheric turbulence and resulting in better astronomical "seeing".[3] Sites that meet the above criteria for modern observatories include the southwestern United States, Hawaii, Canary Islands, the Andes, and high mountains in Mexico such as Sierra Negra.[4] Major optical observatories include Mauna Kea Observatory and Kitt Peak National Observatory in the US, Roque de los Muchachos Observatory in Spain, and Paranal Observatory and Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.[5][6]

Specific research study performed in 2009 shows that the best possible location for ground-based observatory on Earth is Ridge A — a place in the central part of Eastern Antarctica.[7] This location provides the least atmospheric disturbances and best visibility.[citation needed]

Solar observatories

Radio observatories

Beginning in 1933, radio telescopes have been built for use in the field of radio astronomy to observe the Universe in the radio portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. Such an instrument, or collection of instruments, with supporting facilities such as control centres, visitor housing, data reduction centers, and/or maintenance facilities are called radio observatories. Radio observatories are similarly located far from major population centers to avoid electromagnetic interference (EMI) from radio, TV, radar, and other EMI emitting devices, but unlike optical observatories, radio observatories can be placed in valleys for further EMI shielding. Some of the world's major radio observatories include the Very Large Array in New Mexico, United States, Jodrell Bank in the UK, Arecibo in Puerto Rico, Parkes in New South Wales, Australia, and Chajnantor in Chile. A related discipline is Very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI).[citation needed]

Highest astronomical observatories

Since the mid-20th century, a number of astronomical observatories have been constructed at very high altitudes, above 4,000–5,000 m (13,000–16,000 ft). The largest and most notable of these is the Mauna Kea Observatory, located near the summit of a 4,205 m (13,796 ft) volcano in Hawaiʻi. The Chacaltaya Astrophysical Observatory in Bolivia, at 5,230 m (17,160 ft), was the world's highest permanent astronomical observatory[8] from the time of its construction during the 1940s until 2009. It has now been surpassed by the new University of Tokyo Atacama Observatory,[9] an optical-infrared telescope on a remote 5,640 m (18,500 ft) mountaintop in the Atacama Desert of Chile.

Oldest astronomical observatories

The oldest proto-observatories, in the sense of an observation post for astronomy,[17]

- Wurdi Youang, Australia

- Zorats Karer, Karahunj, Armenia

- Loughcrew, Ireland

- Newgrange, Ireland

- Stonehenge, Great Britain

- Chankillo, Peru

- El Caracol, Mexico

- Abu Simbel, Egypt

- Kokino, Kumanovo, North Macedonia

- Observatory at Rhodes, Greece[18]

- Goseck circle, Germany

- Ujjain, India

- Arkaim, Russia

- Cheomseongdae, South Korea

- Angkor Wat, Cambodia

The oldest true observatories, in the sense of a specialized research institute,[17][19][20] include:

- 825: Al-Shammisiyyah Observatory, Baghdad, Iraq

- 869: Mahodayapuram Observatory, Kerala, India

- 1259: Maragheh Observatory, Azerbaijan, Iran

- 1276: Gaocheng Astronomical Observatory, China

- 1420: Ulugh Beg Observatory, Samarqand, Uzbekistan

- 1442: Beijing Ancient Observatory, China

- 1577: Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din, Turkey

- 1580: Uraniborg, Denmark

- 1581: Stjerneborg, Denmark

- 1633: Leiden Observatory, Netherlands

- 1642: Panzano Observatory, Italy

- 1642: Round Tower, Denmark

- 1667: Paris Observatory, France

- 1675: Royal Greenwich Observatory, England

- 1695: Sukharev Tower, Russia

- 1711: Berlin Observatory, Germany

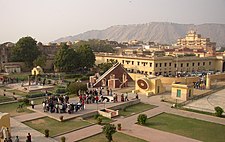

- 1724: Jantar Mantar, India

- 1753: Stockholm Observatory, Sweden

- 1753: Vilnius University Observatory, Lithuania

- 1753: Real Instituto y Observatorio de la Armada, Spain[21]

- 1759: Trieste Observatory, Italy.

- 1757: Macfarlane Observatory, Scotland.

- 1759: Turin Observatory, Italy.

- 1764: Brera Astronomical Observatory, Italy.

- 1765: Mohr Observatory, Indonesia.

- 1771: Lviv Observatory, Ukraine.

- 1774: Observatory of the Vatican, Italy.

- 1785: Dunsink Observatory, Ireland.

- 1786: Madras Observatory, India.

- 1789: Armagh Observatory, Northern Ireland.

- 1790: Royal Observatory of Madrid, Spain,[22]

- 1803: National Astronomical Observatory, Bogotá, Colombia.[23]

- 1811: Tartu Old Observatory, Estonia[24]

- 1812: Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte, Naples, Italy

- 1830/1842: Depot of Charts & Instruments/US Naval Observatory,[25][26] US

- 1830: Yale University Observatory Atheneum, US

- 1834: Helsinki University Observatory, Finland[27]

- 1838: Hopkins Observatory, Williams College, US

- 1838: Loomis Observatory, Western Reserve Academy, US

- 1839: Pulkovo Observatory, Russia

- 1842: Cincinnati Observatory, US

- 1844: Georgetown University Astronomical Observatory, US

- 1847: Harvard College Observatory, US

- 1854: Detroit Observatory, US

- 1873: Quito Astronomical Observatory, Ecuador

- 1878: Lisbon Astronomical Observatory, Portugal

- 1884: McCormick Observatory, US

- 1888: Lick Observatory, US

- 1890: Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, US

- 1894: Lowell Observatory, US

- 1895: Theodor Jacobsen Observatory, US

- 1897: Yerkes Observatory, US

- 1899: Kodaikanal Solar Observatory, India

Space-based observatories

Space-based observatories are telescopes or other instruments that are located in outer space, many in orbit around the Earth. Space telescopes can be used to observe astronomical objects at wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum that cannot penetrate the Earth's atmosphere and are thus impossible to observe using ground-based telescopes. The Earth's atmosphere is opaque to ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, and gamma rays and is partially opaque to infrared radiation so observations in these portions of the electromagnetic spectrum are best carried out from a location above the atmosphere of our planet.[28] Another advantage of space-based telescopes is that, because of their location above the Earth's atmosphere, their images are free from the effects of atmospheric turbulence that plague ground-based observations.[29] As a result, the angular resolution of space telescopes such as the Hubble Space Telescope is often much smaller than a ground-based telescope with a similar aperture. However, all these advantages do come with a price. Space telescopes are much more expensive to build than ground-based telescopes. Due to their location, space telescopes are also extremely difficult to maintain. The Hubble Space Telescope was able to be serviced by the Space Shuttles while many other space telescopes cannot be serviced at all.

Airborne observatories

Airborne observatories have the advantage of height over ground installations, putting them above most of the Earth's atmosphere. They also have an advantage over space telescopes: The instruments can be deployed, repaired and updated much more quickly and inexpensively. The Kuiper Airborne Observatory and the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy use airplanes to observe in the infrared, which is absorbed by water vapor in the atmosphere. High-altitude balloons for X-ray astronomy have been used in a variety of countries.[citation needed]

Neutrino observatories

Example underground, underwater or under ice neutrino observatories include:

- 1998–2003 Gallium Neutrino Observatory

- 1999–2006 Sudbury Neutrino Observatory

- 2003 Baikal Deep Underwater Neutrino Telescope

- 2010 IceCube Neutrino Observatory

- 2012 Helium and Lead Observatory (HALO)

Meteorological observatories

Example meteorological observatories include:

- 1762 Kremsmünster Observatory, Austria

- 1781 Hohenpeißenberg Meteorological Observatory, Germany

- 1841 Colaba Observatory, India

- 1868 Kandilli Observatory, Türkiye

- 1869 New York Meteorological Observatory in Central Park, New York

- 1883 Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong

- 1885 Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory, Massachusetts

- 1932 Mount Washington Observatory, New Hampshire

- 1956 Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii

See also

Marine observatories

A marine observatory is a scientific institution whose main task is to make observations in the fields of meteorology, geomagnetism and tides that are important for the navy and civil shipping. An astronomical observatory is usually also attached. Some of these observatories also deal with nautical weather forecasts and storm warnings, astronomical time services, nautical calendars and seismology.

Example marine observatories include:

- 1676 Royal Greenwich Observatory at London

- 1753 Real Instituto y Observatorio de la Armada in San Fernando, Spain

- 1830 United States Naval Observatory

- 1868 German Maritime Observatory in Hamburg

- 1871–1918 Austro-Hungarian Pola Naval Observatory, in what is now Pula, Croatia

- 1882 Observatoire Oceanologique de Villefranche, France

- 1908 St. Andrews Biological Station, Canada

- 2006 European Multidisciplinary Seafloor and water column Observatory (EMSO)

See also

Magnetic observatories

A magnetic observatory is a facility which precisely measures the total intensity of Earth's magnetic field for field strength and direction at standard intervals. Geomagnetic observatories are most useful when located away from human activities to avoid disturbances of anthropogenic origin, and the observation data is collected at a fixed location continuously for decades. Magnetic observations are aggregated, processed, quality checked and made public through data centers such as INTERMAGNET.[30][31]

The types of measuring equipment at an observatory may include magnetometers (torsion, declination-inclination fluxgate, proton precession, Overhauser-effect), variometer (3-component vector, total-field scalar), dip circle, inclinometer, earth inductor, theodolite, self-recording magnetograph, magnetic declinometer, azimuth compass. Once a week at the absolute reference point calibration measurements are performed.[32]

Example magnetic observatories include:

- 1833 Göttingen Observatory, Germany

- 1840 Toronto Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory, Canada

- 1842 Kew Observatory, UK

- 1904 Eskdalemuir Observatory, UK

- 1961 Boulder Geomagnetic Observatory, Colorado

Seismic observatories

Example seismic observation projects and observatories include:

- International Seismological Summary

- Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory

- EarthScope

- GEOSCOPE Observatory

- World-Wide Standardized Seismograph Network

Geodetic observatories

Cosmic-ray observatories

Gravitational wave observatories

Example gravitational wave observatories include:

Wildlife observatories

Volcano observatories

A volcano observatory is an institution that conducts the monitoring of a volcano as well as research in order to understand the potential impacts of active volcanism. Among the best known are the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory and the Vesuvius Observatory. Mobile volcano observatories exist with the USGS VDAP (Volcano Disaster Assistance Program), to be deployed on demand. Each volcano observatory has a geographic area of responsibility it is assigned to whereby the observatory is tasked with spreading activity forecasts, analyzing potential volcanic activity threats and cooperating with communities in preparation for volcanic eruption.[33]

See also

References

- ^ Udías, Agustín (2003) Searching the Heavens and the Earth Kluwer Academic Publishers p3

- ^ "ALMA's Solitude". Picture of the Week. ESO. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ Chaisson, Eric; McMillan, Steve (2002). Astronomy Today, Fourth Edition. Prentice Hall. pp. 116–119.

- ^ Chaisson, Eric; McMillan, Steve (2002). Astronomy Today, Fourth Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 119.

- ^ Leverington, David (2017) Observatories and Telescopes of Modern Times Cambridge Univ Press ISBN 9780521899932

- ^ Meszaros, Stephen Paul (1986) World Atlas of Large Optical Telescopes NASA TM 87775 p2

- ^ Saunders, Will; Lawrence, Jon S.; Storey, John W. V.; Ashley, Michael C. B.; Kato, Seiji; Minnis, Patrick; Winker, David M.; Liu, Guiping & Kulesa, Craig (2009). "Where Is the Best Site on Earth? Domes A, B, C, and F, and Ridges A and B". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 121 (883): 976–992. arXiv:0905.4156. Bibcode:2009PASP..121..976S. doi:10.1086/605780. S2CID 11166739.

- ^ Zanini, A.; Storini, M.; Saavedra, O. (2009). "Cosmic rays at High Mountain Observatories". Advances in Space Research. 44 (10): 1160–1165. Bibcode:2009AdSpR..44.1160Z. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2008.10.039.

- ^ Yoshii, Yuzuru; et al. (August 11, 2009). "The 1m telescope at the Atacama Observatory has Started Scientific Operation, detecting the Hydrogen Emission Line from the Galactic Center in the Infrared Light". Press Release. School of Science, the University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Taavi Tuvikene, Tartu Old Observatory, 18 February 2009

- ^ Tartu Observatory – Official website (English version)

- ^ Official Web Site of the Sydney Observatory

- ^ "One of the Oldest Observatories in South America is the Quito Astronomical Observatory". Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ Official website of the Quito Astronomical Observatory

- ^ "Slovakia's High Tatras mountains are seen from the solar observatory station on the Lomnicky Stit peak". BBC. 5 September 2014.

- ^ A long time exposed picture taken by night shows Slovakia's High Tatras mountains seen from the Solar observatory station on the Lomnicky Stit peak Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine 4 September 2014.

- ^ a b Micheau, Francoise (1996). "The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East". Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. By Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis. Routledge. pp. 992–3. ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2.

- ^ "Facts about Hipparchus: astronomical observatory, as discussed in astronomical observatory:". Encyclopædia Britannica.[dead link]

- ^ Peter Barrett (2004), Science and Theology Since Copernicus: The Search for Understanding, p. 18, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-567-08969-X

- ^ Kennedy, Edward S. (1962). "Review: The Observatory in Islam and Its Place in the General History of the Observatory by Aydin Sayili". Isis. 53 (2): 237–239. doi:10.1086/349558.

- ^ "Royal Institute and Observatory of the San Fernando Armada". Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ^ "Real Observatorio de Madrid - Breve semblanza histórica". Archived from the original on 2013-07-26.

- ^ "Observatorio Astronómico Nacional (Universidad Nacional de Colombia)". Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ^ "On its 200th Anniversary Tartu Old Observatory Opens Doors as a Museum". Visit Estonia. 26 April 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Astronomy and Astrophysics (United States Naval Observatory)". Heritage Preservation Services, National Park Service. 2001-11-05. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ^ Portolano, M. (2000). "John Quincy Adams's Rhetorical Crusade for Astronomy". Isis. 91 (3): 480–503. doi:10.1086/384852. JSTOR 237905. PMID 11143785. S2CID 25585014 – via Zenodo.

- ^ History of astronomy at University of Helsinki 1834–1984 (in Finnish)

- ^ Chaisson, Eric; McMillan, Steve (2002). Astronomy Today, Fourth Edition. Prentice Hall.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Hubble Space Telescope: Why a Space Telescope?". NASA. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

- ^ Gupta, Harsh (ed) (2021) Encyclopedia of Solid Earth Geophysics Springer ISBN 9783030586300 p774

- ^ Principal Facts of the Earth's Magnetism U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1919 pp57-59

- ^ Jankowski, J. and Sucksdorff, C. (1996) IAGA Guide for Magnetic Measurements and Observatory Practice ISBN 0965068625

- ^ "USGS operates five U.S. Volcano Observatories". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

Further reading

- Aubin, David; Charlotte Bigg, and H. Otto Sibum, eds. The Heavens on Earth: Observatories and Astronomy in Nineteenth-Century Science and Culture (Duke University Press; 2010) 384 pages; Topics include astronomy as military science in Sweden, the Pulkovo Observatory in the Russia of Czar Nicholas I, and physics and the astronomical community in late 19th-century America.

- Brunier, Serge, et al. Great Observatories of the World (2005)

- Dick, Steven. Sky and Ocean Joined: The U.S. Naval Observatory 1830–2000 (2003)

- Gressot Julien and Jeanneret Romain, « Determining the right time, or the establishment of a culture of astronomical precision at Neuchâtel Observatory in the mid-19th century », Journal for the History of Astronomy, 53(1), 2022, 27–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/00218286211068572

- Leverington, David. Observatories and Telescopes of Modern Times - Ground-Based Optical and Radio Astronomy Facilities since 1945. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2017, ISBN 9780521899932.

- McCray, W. Patrick. Giant Telescopes: Astronomical Ambition and the Promise of Technology (2004); focuses on the Gemini Observatory.

- Sage, Leslie, and Gail Aschenbrenner. A Visitor's Guide to the Kitt Peak Observatories (2004)

External links

- Western Visayas Local Urban Observatory (archived 19 September 2008)

- Dearborn Observatory Records, Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, Illinois (archived 4 September 2015)

- Coordinates and satellite images of astronomical observatories on Earth

- Milkyweb Astronomical Observatory Guide world's largest database of astronomical observatories since 2000 – about 2000 entries

- List of amateur and professional observatories in North America with custom weather forecasts

- Map showing many of the Astronomical Observatories around the world (with drilldown links)

- Mt. Wilson Observatory