Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

| Naval operations in the Dardanelles campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gallipoli campaign | |||||||

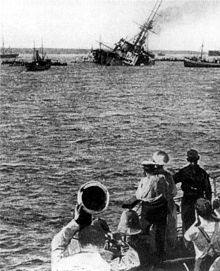

The final moments of the French battleship Bouvet, 18 March 1915 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The naval operations in the Dardanelles campaign (17 February 1915 – 9 January 1916) took place against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. Ships of the Royal Navy, French Marine nationale, Imperial Russian Navy (Российский императорский флот) and the Royal Australian Navy, attempted to force a passage through the Dardanelles Straits, a narrow, 41-mile-long (66 km) waterway connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea further north.

The naval operations were defeated by the Ottoman defenders, mainly through use of naval mines. The Allies conducted the Gallipoli campaign, a land invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula to eliminate the Ottoman artillery along the straits before resuming naval operations. The Allies also passed submarines through the Dardanelles to attack Ottoman shipping in the Sea of Marmara.

Background

Dardanelles Strait

The mouth of the strait is 2.3 mi (3.7 km) wide with a rapid current emptying from the Black Sea into the Aegean. The distance from Cape Helles to the Sea of Marmara is about 41 mi (66 km), overlooked by the heights on the Gallipoli peninsula and lower hills on the Asiatic shore. The passage widens for 5 mi (8.0 km) to Eren Keui Bay, the widest point of the strait at 4.5 mi (7.2 km), then narrows for 11 mi (18 km) to Kephez Point, where the waterway is 1.75 mi (2.82 km) wide and then broadens as far as Sari Sighlar Bay. The narrowest part of the strait is 14 mi (23 km) upstream, from Chanak to Kilid Bahr at 1,600 yd (1,500 m), where the channel turns north and widens for 4 mi (6.4 km) to Nagara Point. From the point, the passage turns north-east for the final 23 mi (37 km) to the Sea of Marmara. The Ottomans used the term "fortress" to describe the sea defences of the Dardanelles on both sides of the waterway from the Aegean approaches to Chanak. In 1914 only the defences from the entrance of the straits and 4 mi (6.4 km) from the north end of Kephez Bay to Chanak had been fortified. Until late October 1914, the nature of the seaward defences of the Dardanelles was known to the British and French but after hostilities commenced, information on improvements to the Ottoman fortifications became harder to obtain.[1]

Ottoman entry into the war

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire had a reputation as the sick man of Europe.[2] After the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, the French, British and Germans had offered financial aid.[3] In December 1913, the Germans sent a military mission to Constantinople, headed by General Otto Liman von Sanders. The geographical position of the Ottoman Empire meant that Russia, France and Britain had a significant interest in Ottoman neutrality.[4] During the Sarajevo Crisis in 1914, German diplomats offered Turkey an anti-Russian alliance and territorial gains, when the pro-British faction in the Cabinet was isolated, due to the British ambassador's absence.[5] On 30 July 1914, two days after the outbreak of the war in Europe, the Ottoman leaders, unaware that the British might enter a European war, agreed to a secret Ottoman-German Alliance against Russia, although it did not require them to undertake military action.[6][7][4]

On 2 August, the British requisitioned the modern battleships Sultân Osmân-ı Evvel and Reşadiye which British shipyards had been building for the Ottoman Navy, alienating pro-British elements. The German government offered SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau as replacements. In the Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau, the ships escaped when the Ottoman government opened the Dardanelles to them, despite international law requiring a neutral party to block military shipping.[8] In September, the British naval mission to the Ottomans was recalled and Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon of the Imperial German Navy took command of the Ottoman navy.[9] The German naval presence, and the success of the German armies, gave the pro-German faction in the Ottoman government enough influence to declare war on Russia.[10]

Closure of the Dardanelles

In October 1914, following an incident on 27 September, when the British Dardanelles squadron had seized an Ottoman torpedo boat, the German commander of the Dardanelles fortifications ordered the passage closed, adding to the impression that the Ottomans were pro-German.[11][12] Hostilities began on 28 October, when the Ottoman fleet, including Goeben and Breslau (flying the Ottoman flag and renamed Yavûz Sultân Selîm and Midilli but still commanded by German officers and manned by German crews) conducted the Black Sea Raid. Odessa and Sevastopol were bombarded, and a Russian minelayer and gunboat were sunk. [13] The Ottomans refused an Allied demand that they expel the German missions and on 31 October 1914, formally joined the Central Powers.[14][15] Russia declared war on Turkey on 2 November and the British ambassador left Constantinople the next day.[citation needed]

A British naval squadron bombarded the Dardanelles outer defensive forts at Kum Kale and Seddulbahir; a shell hit a magazine and the explosion knocked the guns off their mounts and killed 86 soldiers. Britain and France declared war on Turkey on 5 November and the Ottomans declared a jihad (holy war) later that month.[16] The Caucasus campaign, an Ottoman attack on Russia through the Caucasus Mountains began in December, leading the Russians to call for aid from Britain in January 1915.[13] The Mesopotamian campaign began with a British landing to occupy the oil facilities in the Persian Gulf.[17] The Ottomans prepared to attack Egypt in early 1915, to occupy the Suez Canal and cut the Mediterranean route to British India and the Far East.[18]

Prelude

Allied strategy

Field Marshal Lord Kitchener planned an amphibious landing near Alexandretta in Syria in 1914, to sever the capital from Syria, Palestine and Egypt.[19] Vice Admiral Sir Richard Peirse, Commander-in-Chief, East Indies, ordered HMS Doris to Alexandretta on 13 December 1914 as the Russian cruiser Askold and the French cruiser Requin were performing similar operations. The Alexandretta landing was abandoned because it required more resources than France could allocate, and politically France did not want the British operating in their sphere of influence, a position to which Britain had agreed in 1912.[20] By late 1914, static warfare had begun on the Western Front, with no prospect of a quick decisive victory and the Central Powers had closed the overland trade routes between Britain, France and Russia. The White Sea in the Arctic and the Sea of Okhotsk in the Far East were icebound in winter and the Baltic Sea was blockaded by the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy). Ottoman belligerence closed the Dardanelles, the remaining supply route to Russia.[21][4][22]

In November 1914, the French Minister Aristide Briand proposed an attack on the Ottoman Empire but the idea was rejected and an attempt by the British to buy off the Ottomans also failed.[23] On 2 January 1915, Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia appealed to Britain for assistance against the Ottoman Erzurum Offensive in the Caucasus and planning began for a naval demonstration in the Dardanelles, as a diversion.[24] Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, proposed an invasion of Schleswig-Holstein by sea, drawing Denmark into the war and re-opening the Baltic Sea route to Russia and an attack on the Dardanelles, to control the Mediterranean-Black Sea supply route and to encourage Bulgaria and Romania to join the Allies. The urgency of the Russian appeal and disdain for the military power of the Ottoman Empire made a campaign in the Dardanelles appear feasible.[25]

On 11 January 1915, the commander of the British Mediterranean Squadron, Vice Admiral S. H. Carden proposed a plan for forcing the Dardanelles using battleships, submarines and minesweepers. On 13 February, the British War Council approved the plan and Carden was given more pre-dreadnought battleships, the modern battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth and the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible. France contributed a squadron including four pre-dreadnoughts and the Russian navy provided the light cruiser Askold. In early February 1915, the naval forces were supplemented by contingents of Royal Marines and the 29th Division, the last uncommitted regular division, which joined Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) divisions training in Egypt. The infantry were intended for the occupation of Constantinople after the straits had been taken by the Entente navies.[26]

Dardanelles defences

In August 1914, the Outer Defences were two fortresses at the end of the Gallipoli peninsula and two on the Asiatic shore. The forts had 19 guns, four with a range of 9 mi (14 km) and the remainder with ranges of 3.4–4.5 mi (5.5–7.2 km). Four field howitzers were dug in at Tekke Burnu (Cape Tekke) on the European side, then for the next 10 mi (16 km), there was a gap until the Intermediate Defences at Kephez Point, with four defensive works on the south shore and one on the north shore. The fortresses had been built to cover a minefield, which in August 1914 was a line of mines across the strait from Kephez Point to the European shore. Fort Dardanos was the main work which had two new 6-inch naval guns and the rest contained ten small quick-firing guns with shields. At the Narrows, the Inner Defences had the heaviest guns and some mobile light howitzers and field guns. Five forts had been built on the European side and six on the Asian side with 72 heavy and medium guns. Most of the artillery was obsolescent but there were five long-range 14 in (360 mm) guns with a range of 9.7 mi (15.6 km) and three 9.4 in (240 mm) guns with a 8.5 mi (13.7 km) range. The remainder of the guns in the Inner Defences were mostly obsolete and unable to shoot beyond 5.7 mi (9.2 km).[27]

Of the 100 guns in the pre-war defences, only 14 were modern long-range pieces, the rest being old-fashioned breech loaders on fixed carriages. The gunners were poorly trained, there was little ammunition and scant prospect of replacement. Night illumination consisted of a searchlight at entrance to the Straits and one at the Narrows. The forts were easily visible, there were few gun shields and other protective features for the gun-crews and range-finding, artillery observation and fire-control depended on an telephones linked by wire on telephone poles, vulnerable to artillery-fire.[28] The Ottoman official historian wrote,

On mobilisation, the fortification and armament of the Dardanelles was very inadequate. Not only were the majority of the guns of old pattern, with a slow rate of fire and short range, but their ammunition supply was also limited.

— Ottoman Official History[28]

Ottoman strategy

The Germans secured the appointment of Lieutenant-General Erich Weber as an advisor to the Ottoman GHQ and at the end of August 1914, Vice-Admiral Guido von Usedom, several specialists and 500 men were sent to reinforce the forts on the Dardanelles and Bosphorus. In September, Usedom was made Inspector-General of Coast Defences and Mines and Vice-Admiral Johannes Merten relieved Weber at Chanak with a marine detachment to operate the modern guns. By mid-September, the German advisers reported that the guns in the Narrows had been refurbished and were serviceable. By October, most of the guns in the main batteries had German crews, operating as training units but able to man the guns in an emergency. Plans were made to build more defensive works in the Intermediate Zone and to bring in mobile howitzers and quick-firers dismounted from older Ottoman ships. Several heavy howitzers arrived in October but the poor standard of training of the Ottoman gunners, obsolete armaments and the chronic ammunition shortage, which Usedom reported was sufficient only to defend against one serious attack, led him to base the defence of the straits on minefields.[29]

Three more lines of mines had been laid before Usedom arrived and another 145 mines were searched out, serviced and laid in early November. Cover of the minefields was increased with small quick-firers and four more searchlights. By March 1915, there were ten lines of mines and 12 searchlights. When the Ottoman Empire went to war on 29 October 1914, the defences of the Straits had been much improved but the Intermediate Defences were still inadequately organised and lacking in guns, searchlights and mines. On 3 November, the outer forts were bombarded by Allied ships, which galvanised the Ottoman defenders into reducing their obstructionism against the German advisers. The fortress commander, Jevad Pasha, wrote later that he had to improve the defences at all costs. The short bombardment had been extraordinarily successful, destroying the forts at Sedd el Bahr with two shots, that exploded the magazine and dismounted the guns. The Ottoman and German defenders concluded that the Outer Defences could be demolished by ships firing from beyond the range of the Ottoman reply. The forts were repaired but not reinforced and the main effort was directed to protecting the minefield and Inner Defences.[30]

Naval operations

Forcing the straits

On 3 November 1914, Churchill ordered an attack on the Dardanelles following the opening of hostilities between Ottoman and Russian empires. The battlecruisers of the Mediterranean Squadron, HMS Indomitable and Indefatigable and the obsolete French battleships Suffren and Vérité, attacked before a formal declaration of war had been made by Britain against the Ottoman Empire. The attack was to test the Ottoman defences and in a twenty-minute bombardment, a shell struck the magazine of the fort at Sedd el Bahr, dismounting ten guns and killing 86 Ottoman soldiers. Total casualties during the attack were 150, of which forty were German. The effect of the bombardment alerted the Ottomans to the importance of strengthening their defences and they began laying more mines.[31]

The outer defences lay at the entrance to the straits, vulnerable to bombardment and raiding but the inner defences covered the Narrows near Çanakkale. Beyond the inner defences, the straits were virtually undefended but the defence of the straits depended on ten minefields, with 370 mines laid near the Narrows. On 19 February 1915, two destroyers were sent in to probe the straits and the first shot was fired from Kumkale by the 240 mm (9.4 in) Krupp guns of the Orhaniye Tepe battery at 07:58. The battleships HMS Cornwallis and Vengeance moved in to engage the forts and Cornwallis opened fire at 09:51.[32] The effect of the long-range bombardment was considered disappointing and that it would take direct hits on guns to knock them out. With limited ammunition, indirect fire was insufficient and direct fire would need the ships to be anchored to make stable gun platforms. Ottoman casualties were reported as several men killed on the European shore and three men at Orkanie.[33][34]

On 25 February the Allies attacked again, the Ottomans evacuated the outer defences and the fleet entered the straits to engage the intermediate defences. Demolition parties of Royal Marines raided the Sedd el Bahr and Kum Kale forts, meeting little opposition. On 1 March, four battleships bombarded the intermediate defences but little progress was made clearing the minefields. The minesweepers, commanded by the chief of staff, Roger Keyes, were un-armoured trawlers manned by their civilian crews, who were unwilling to work while under fire. The strong current in the straits further hampered minesweeping and strengthened Ottoman resolve which had wavered at the start of the offensive; on 4 March, twenty-three marines were killed raiding the outer defences.[35]

Queen Elizabeth was called on to engage the inner defences, at first from the Aegean coast near Gaba Tepe, firing across the peninsula and later in the straits. On the night of 13 March, the cruiser HMS Amethyst led six minesweepers in an attempt to clear the mines. Four of the trawlers were hit and Amethyst was badly damaged with nineteen stokers killed from one hit. On 15 March, the Admiralty accepted a plan by Carden for another attack by daylight, with the minesweepers protected by the fleet. Carden was taken ill the same day and was replaced by Rear Admiral John de Robeck. A gunnery officer noted in his diary that de Robeck had already expressed misgivings about silencing the Ottoman guns by naval bombardment and that this view was widely held on board the ship.[36][37]

Battle of 18 March

The event that decided the battle took place on the night of 18 March when the Ottoman minelayer Nusret laid a line of mines in front of the Kephez minefield, across the head of Eren Köy Bay, a wide bay along the Asian shore just inside the entrance to the straits. The Ottomans had noticed the British ships turned to starboard into the bay when withdrawing.[38] The new row of 20 mines ran parallel to the shore, were moored at fifteen m (49.2 ft) and spaced about 100 yd (91 m) apart. The clear water meant that the mines could have been seen through the water by reconnaissance aircraft.[39] The British plan for 18 March was to silence the defences guarding the first five minefields, which would be cleared overnight by the minesweepers. The next day the remaining defences around the Narrows would be defeated and the last five minefields would be cleared. The operation went ahead with the British and French ignorant of the recent additions to the Ottoman minefields. The battleships were arranged in three lines, two British and one French, with supporting ships on the flanks and two ships in reserve.[40]

| Line A | HMS Queen Elizabeth | Agamemnon | Lord Nelson | Inflexible |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| French Line B | Gaulois | Charlemagne | Bouvet | Suffren |

| British Line B | HMS Vengeance | Irresistible | Albion | Ocean |

| Supporting ships | HMS Majestic | Prince George | Swiftsure | Triumph |

| Reserve | HMS Canopus | Cornwallis |

The first British line opened fire from Eren Köy Bay around 11:00. Shortly after noon, de Robeck ordered the French line to pass through and close on the Narrows forts. The Ottoman fire began to take its toll with Gaulois, Suffren, Agamemnon and Inflexible suffering hits. While the naval fire had not destroyed the Ottoman batteries, it had succeeded in temporarily reducing their fire. By 13:25, the Ottoman defences were mostly silent so de Robeck decided to withdraw the French line and bring forward the second British line as well as Swiftsure and Majestic.[42]

The Allied forces had failed to properly sweep the entire area for mines. Aerial reconnaissance by aircraft from the seaplane carrier HMS Ark Royal had discovered a number of mines on 16 and 17 March but failed to spot the line of mines laid by Nusret in Eren Köy Bay.[43] On the day of the attack civilian trawlers sweeping for mines in front of line "A" discovered and destroyed three mines in an area thought to be clear, before the trawlers withdrew under fire. This information was not passed on to de Robeck.[44] At 13:54, Bouvet—having made a turn to starboard into Eren Köy Bay—struck a mine, capsized and sank within a couple of minutes, killing 639 crewmen, only 48 survivors being rescued. At first it appeared that the ship had been hit in a magazine and de Robeck thought that the ship had struck a floating mine or been torpedoed.[45][46]

The British pressed on with the attack. Around 16:00, Inflexible began to withdraw and struck a mine near where Bouvet had sunk, thirty crew being killed and the ship taking on with 1,600 long tons (1,600 t) of water.[47] The battlecruiser remained afloat, was eventually beached on the island of Bozcaada (Tenedos) and temporarily repaired with a coffer dam.[48] Irresistible was the next to be mined and as it began to drift, the crew were taken off. De Robeck told Ocean to take Irresistible under tow but the water was deemed too shallow to make an approach. At 18:05, Ocean struck a mine which jammed the steering gear leaving the ship adrift. The abandoned battleships were still floating when the British withdrew but when a destroyer commanded by Commodore Roger Keyes returned to tow or sink the vessels, they could not be found despite a 4-hour search.[49]

In 1934, Keyes wrote that

The fear of their fire was actually the deciding factor of the fortunes of the day. For five hours the [destroyer] Wear and picket boats had experienced, quite unperturbed and without any loss, a far more intense fire from them than the sweepers encountered... the latter could not be induced to face it, and sweep ahead of the ships in 'B' line.... I had the almost indelible impression that we were in the presence of a beaten foe. I thought he was beaten at 2 pm. I knew he was beaten at 4 pm – and at midnight I knew with still greater clarity that he was absolutely beaten; and it only remained for us to organise a proper sweeping force and devise some means of dealing with drifting mines to reap the fruits of our efforts.

— Keyes[50]

For 118 casualties, the Ottomans sank three battleships, severely damaged three others and inflicted seven hundred casualties on the British-French fleet. There were calls amongst the British, particularly from Churchill, to press on with the naval attack and De Robeck advised on 20 March that he was reorganising his minesweepers. Churchill responded that he was sending four replacement ships; with the exception of Inflexible, the ships were expendable. It is not correct that the ammunition of the guns was low: they could have repulsed two more attacks.[51] The crews of the sunken battleships replaced the civilians on the trawler minesweepers and were much more willing to keep sweeping under fire.[52] The US Ambassador to Constantinople, Henry Morgenthau, reported that Constantinople expected to be attacked and that the Ottomans felt they could only hold out for a few hours if the attack had resumed on 19 March.[53] Further, he thought that Turkey itself might well disintegrate as a state once the capital fell.[54]

The main minefields at the narrows, over ten layers deep, were still intact and protected by the smaller shore guns that had not seen any action on 18 March. These and other defences further in the strait had not exhausted their ammunition and resources yet. It was not a given that one more push by the fleet would have resulted in passage to Marmara Sea. Churchill had anticipated losses and considered them a necessary tactical price. In June 1915, he discussed the campaign with the war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, who had returned to London to deliver uncensored reports. Ashmead-Bartlett was incensed at the loss of ships and lives but Churchill responded that the ships were expendable.[55][56] To place the losses into perspective, the Navy had ordered six hundred new ships during the period Admiral Fisher was First Sea Lord, approximately corresponding with the length of the Dardanelles campaign.[57]

De Robeck wrote on 18 March,

After losing so many ships I shall obviously find myself superseded tomorrow morning.[53]

The fleet lost more ships than the Royal Navy had suffered since the Battle of Trafalgar; on 23 March, de Robeck telegraphed to the Admiralty that land forces were needed. He later told the Dardanelles Commission investigating the campaign, that his main reason for changing his mind, was concern for what might happen in the event of success, that the fleet might find itself at Constantinople or on the Marmara sea fighting an enemy which did not simply surrender as the plan assumed, without any troops to secure captured territory.[58] With the failure of the naval assault, the idea that land forces could advance around the backs of the Dardanelles forts and capture Constantinople gained support as an alternative and on 25 April, the Gallipoli campaign commenced.[59]

Further naval plans

Following the failure of the land campaign up to May, De Robeck suggested that it might be desirable to again attempt a naval attack. Churchill supported this idea, at least as far as restarting attempts to clear mines but this was opposed by Fisher and other members of the Admiralty Board. Aside from difficulties in the Dardanelles, they were concerned at the prospect that more ships might have to be diverted away from the Grand Fleet in the North Sea. This disagreement contributed to the final resignation of Fisher, followed by the need for Asquith to seek coalition partners to shore up his government and the consequential dismissal of Churchill also. Further naval attacks were shelved.[60]

Keyes remained a firm supporter of naval action and on 23 September submitted a further proposal to pass through the Dardanelles to de Robeck. De Robeck disliked the plan but passed it to the Admiralty. Risk to ships had increased since March, due to the presence of German submarines in the Mediterranean and the Sea of Marmara, where the British ships would be inviting targets if the plan succeeded. The Allied minesweeping force was better equipped and some of the ships had nets or mine bumpers, which it was hoped would improve their chances against mines. The Ottoman Empire had regained land communications with Germany since the fall of Serbia and demands on the Anglo-French navies for more ships to support the attempt had to be added to the commitment of ships for the land campaign and operations at Salonica attempting to support Serbia. Kitchener made a proposal to take the Isthmus of Bulair using forty thousand men to allow British ships operating in the Marmara Sea to be supplied across land from the Gulf of Xeros. Admiralty opinion was that another naval attack could not be mounted without support of land forces attacking the Dardanelles forts, which was deemed impractical for lack of troops. Kitchener visited the area to inspect the positions and talk to the commanders concerned, before reporting back advising a withdrawal. The War Committee, faced with a choice either of an uncertain new campaign to break the stalemate or complete withdrawal, recommended on 23 November that all troops should be withdrawn.[61]

The British cabinet as a whole was less keen to abandon the campaign, because of political repercussions of a failure and damaging consequences for Russia. De Robeck had been temporarily replaced by Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss in November 1915 for reasons of ill health. In contrast to De Robeck, Wemyss was a supporter of further action and considerably more optimistic of chances of success. Whereas de Robeck estimated losses at 12 battleships, Wemyss considered it likely to lose no more than three. It was suggested that liquidating the Salonica commitment, where the troops involved never managed to aid Serbia and did little fighting, could provide the reinforcements but this was vetoed by the French. Wemyss continued a campaign promoting the chances of success. He had been present when de Robeck assumed command from Carden and was more senior but had been commanding the base at Mudros whereas de Robeck was with the fleet. Churchill had preferentially chosen de Robeck.[62] On 7 December, it was decided by Cabinet to abandon the campaign.[63]

Submarine operations

British submarine attacks had commenced in 1914, before the campaign proper had started. On 13 December, the submarine HMS B11 (Lieutenant-Commander Norman Holbrook) had entered the straits, avoiding five lines of mines and torpedoed the Ottoman battleship Mesûdiye, built in 1874, which was anchored as a floating fort in Sari Sighlar Bay, south of Çanakkale. Mesûdiye capsized in ten minutes, trapping many of the 673-man crew. Lying in shoal water, the hull remained above the surface so most men were rescued by cutting holes in the hull but 37 men were killed. The sinking was a triumph for the Royal Navy. Holbrook was awarded the Victoria Cross—the first Royal Navy VC of the war—and all twelve other crew members received awards. Coupled with the naval bombardment of the outer defences on 3 November, this success encouraged the British to pursue the campaign.[64]

The first French submarine operation also preceded the start of the campaign; on 15 January 1915, the French submarine Saphir negotiated the Narrows, passing the ten lines of mines before running aground at Nagara Point. Various accounts claim she was either mined, sunk by shellfire or scuttled, leaving fourteen crew dead and thirteen prisoners of war. On 17 April, the British submarine HMS E15 attempted to pass the straits but having dived too deep, was caught in a current and ran aground near Kepez Point, the southern tip of Sarı Sıĝlar Bay, under the guns of the Dardanos battery. Seven of the crew were killed and the remainder were captured. The beached E15 was a valuable prize for the Ottomans and the British went to great lengths to deny it to them and managed to sink it after numerous attempts.[65]

The first submarine to pass the straits was the Australian HMAS AE2 (Lieutenant-Commander Henry Stoker) which got through on the night of 24/25 April. The army landings at Cape Helles and Anzac Cove began at dawn on 25 April. Although AE2 sank one Ottoman destroyer, thought to be a cruiser, the submarine was thwarted by defective torpedoes in several other attacks. On 29 April, in Artaki Bay near Panderma, AE2 was sighted and hit by the Ottoman torpedo boat Sultanhisar. Abandoning ship, the crew was taken prisoner.[66][b]

The second submarine through the straits had more luck than AE2. On 27 April, HMS E14 (Lieutenant-Commander Edward Boyle), entered the Sea of Marmara and went on a three-week sortie that was one of the most successful actions of the Allies in the campaign. The quantity and value of the shipping sunk was relatively minor but the effect on Ottoman communications and morale was significant. On his return, Boyle was immediately awarded the Victoria Cross. Boyle and E14 made a number of tours of the Sea of Marmara. His third tour began on 21 July, when he passed the straits, despite the Ottomans having installed an anti-submarine net near the Narrows. HMS E11 (Lieutenant-Commander Martin Nasmith) also cruised the Sea of Marmara and Nasmith was awarded the VC and promoted to Commander for his achievements. E11 sank or disabled eleven ships, including three on 24 May at the port of Rodosto on the Thracian shore. On 8 August, during a later tour of the Marmara, E11 torpedoed the Barbaros Hayreddin.[68]

A number of demolition missions were performed by men or parties landed from submarines. On 8 September, First Lieutenant H. V. Lyon from HMS E2 swam ashore near Küçükçekmece (Thrace) to blow up a railway bridge. The bridge was destroyed but Lyon failed to return.[69] Attempts were also made to disrupt the railways running close to the water along the Gulf of İzmit, on the Asian shore of the sea. On the night of 20 August, Lieutenant Guy D'Oyly-Hughes from E11 swam ashore and blew up a section of the railway line.[70] On 17 July, HMS E7 bombarded the railway line and then damaged two trains that were forced to halt.[71]

French attempts to enter the Sea of Marmara continued. Following the success of AE2 and E14, the French submarine Joule attempted the passage on 1 May but she struck a mine and was lost with all hands.[72] The next attempt was made by Mariotte on 27 July. Mariotte was caught in the anti-submarine net that E14 had eluded and was forced to the surface. After being shelled from the shore batteries, Mariotte was scuttled.[73] On 4 September, the same net caught E7 as it began another tour.[74]

The first French submarine to enter the Sea of Marmara was Turquoise but it was forced to turn back and on 30 October, when returning through the straits, ran aground beneath a fort and was captured intact. The crew of twenty-five were taken prisoner and documents detailing Allied operations were discovered, which included a rendezvous with HMS E20 scheduled for 6 November. The rendezvous was kept by the German U-boat UB-14 which torpedoed and sank E20 killing all but nine of the crew. Turquoise was salvaged and incorporated (but not commissioned) into the Ottoman Navy as the Onbasi Müstecip, named after the gunner who had forced the French commander to surrender.[75]

The Allied submarine campaign in the Sea of Marmara was the one significant success of the Gallipoli campaign, forcing the Ottomans to abandon it as a transport route. Between April and December 1915, nine British and four French submarines sank one battleship, one destroyer, five gunboats, eleven troop transports, forty-four supply ships and 148 sailing vessels at a cost of eight Allied submarines sunk in the strait or in the Sea of Marmara.[76][c]

Military operations

Gallipoli landings

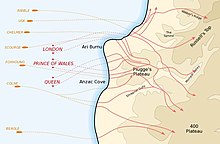

The Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (General Sir Ian Hamilton) was established on 12 March with about 70,000 men.[78] At a conference on 22 March, four days after the failed attempt by the navy, it was decided to use the infantry to seize the Gallipoli peninsula and capture the forts, clearing the way for the navy to pass through into the Sea of Marmara. Preparations for the landing took a month, giving the Ottoman defenders ample time to reinforce. The British planners underestimated the Ottomans and expected that the invasion would be over swiftly.[79] The initial landings were made at Gaba Tepe by the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac). The landing miscarried and the troops went ashore too far north at a place now known as Anzac Cove. In both landings, the covering force went ashore from warships with the exception of V Beach at Helles where the SS River Clyde was used as an improvised landing craft for 2,000 men. In the landing at Anzac Cove, the first wave went ashore from the boats of three Formidable-class battleships, HMS London, Prince of Wales and Queen. The second wave went ashore from seven destroyers. In support were HMS Triumph, Majestic and the cruiser HMS Bacchante as well as the seaplane carrier Ark Royal and the kite-balloon ship, HMS Manica, from which a tethered balloon was trailed to provide artillery spotting.[80]

The landing at Cape Helles by the 29th Division was spread over five beaches with the main ones being V and W Beaches at the tip of the peninsula. While the landing at Anzac was planned as a surprise without a preliminary bombardment, the Helles landing was made after the beaches and forts were bombarded by the warships. The landing at S Beach inside the straits was made from the battleship Cornwallis and was virtually unopposed. The W Beach force came from the cruiser HMS Euryalus and the battleship HMS Implacable which also carried the troops bound for X Beach. The cruiser HMS Dublin and battleship Goliath supported the X Beach landing as well as a small landing to the north on the Aegean coast at Y Beach, later abandoned.[citation needed]

The navy was to support the landing, using naval guns as substitutes for field artillery, of which there was a severe shortage. With a few spectacular exceptions, the performance of naval guns on land targets was inadequate, particularly against entrenched positions. The guns lacked elevation and so fired on a flat trajectory which, coupled with the inherently unstable gun platform, resulted in reduced accuracy. The battleships' guns did prove effective against exposed lines of troops. On 27 April, during the first Ottoman counter-attack at Anzac, the Ottoman 57th Infantry Regiment attacked down the seaward slope of Battleship Hill within view of Queen Elizabeth which fired a salvo of six fifteen in (380 mm) shells, halting the attack.[81] On 28 April, near the old Y Beach landing, Queen Elizabeth sighted a party of about one hundred Turks. One 15-inch shrapnel shell containing 13,000 shrapnel bullets was fired at short range and killed the entire party.[82]

On 27 April, an observer on a kite-balloon ship had spotted an Ottoman transport ship moving near the Narrows. Queen Elizabeth, stationed off Gaba Tepe, had fired across the peninsula at a range of over ten mi (8.7 nmi; 16 km), and sank the transport with the third shot.[83] For much of the campaign, the Ottomans transported troops via rail, though other supplies continued to be moved by ship on the Sea of Marmara and Dardanelles. At Helles, which was initially the main battlefield, a series of costly battles only managed to edge the front line closer to Krithia. The navy continued to provide support via bombardments but in May, the battleship Goliath was sunk by the Ottoman torpedo boat Muâvenet-i Millîye in Morto Bay on 12 May and U-21 torpedoed and sank Triumph off Anzac on 25 May and Majestic off W Beach on 27 May.[84][85]

Permanent battleship support was withdrawn with the valuable Queen Elizabeth recalled by the Admiralty as soon as the news of the loss of Goliath arrived. In place of the battleships, naval artillery support was provided by cruisers, destroyers and purpose-built monitors which were designed for coastal bombardment. Once the navy became wary of the submarine threat, losses ceased.[86] With the exception of the continued activity of Allied submarines in the Dardanelles and Sea of Marmara, the only significant naval loss after May was the Laforey-class destroyer HMS Louis which ran aground off Suvla during a gale on 31 October and was wrecked. The destruction of the stranded ship was accelerated by Ottoman gunfire.[87]

Troop transports

Another important aspect of the allied naval operations was transporting thousands of soldiers to and from the Dardanelles over the Mediterranean Sea. The major threats were attacks by German and Austrian-Hungarian submarines and mines. The worst loss during the Dardanelles Campaign was the sinking of HMT Royal Edward on 13 August 1915. The ship sailed from Alexandria, Egypt to Gallipoli with 1,367 officers and men on board and was torpedoed by SM UB-14 near the Dodecanese, with 935 lives lost.[88]

See also

- Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau

- List of Allied warships that served at Gallipoli

- All the King's Men (1999 film)

- Coastal artillery of the Dardanelles Strait

Notes

- ^ Hamilton's left hand, partially disabled by a wound in the First Boer War, is clearly visible.

- ^ The wreck was found in 1997 and the Turkish and Australian governments later agreed to leave the wreck alone.[67]

- ^ In 1993, a coal mining operation revealed the wreck of the German submarine UB-46 near the Kemerburgaz coast. After carrying out missions in Black Sea, UB-46 hit a mine near Karaburun and sank with all hands. It is now on display at Besiktas Naval Museum in Istanbul.[77]

References

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, pp. 37–41.

- ^ a b c Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, pp. 9, 18.

- ^ Howard 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 45.

- ^ a b Carlyon 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Holmes 2001, p. 577.

- ^ Keegan 1998, p. 238.

- ^ Erickson 2013, p. 159.

- ^ Tauber 1993, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Corbett 2009, pp. 158, 166.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Strachan 2003, p. 115.

- ^ Travers 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 140–157.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Aspinall-Oglander 1929, p. 33.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Marder 1965, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 157–183.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 206–210.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 290–316.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 213–224.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 216–217, 223, 225.

- ^ Layman 1987, p. 151.

- ^ IWM p. 12.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1929, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 221–223.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Keyes 1934, pp. 237–238, 245.

- ^ Ōzakman 2008, p. 686.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b Carlyon 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Morgenthau 1918, xviii.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 320.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 223–22.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 260.

- ^ Marder 1965, p. 252.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 225–230, 316–349.

- ^ Marder 1965, p. 275.

- ^ Marder 1965, pp. 314–320.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 265.

- ^ Marder 1965, pp. 320–324.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, p. 140.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 310, 347, 357, 374–375.

- ^ HCNSW 2017.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, p. 119.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 115–117.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, p. 374.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, p. 78.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 177, 179, 205–206.

- ^ O'Connell 2010, pp. 76–78.

- ^ "Sergi Alanları". 19 September 2008. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 208–211.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, p. 355.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, p. 362.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, p. 359.

- ^ Corbett 2009a, pp. 407–408.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 24, 37, 43.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, p. 212.

- ^ Corbett 2009b, pp. 112–113.

Bibliography

Books

- Aspinall-Oglander, Cecil Faber (1929). Military Operations Gallipoli: Inception of the Campaign to May 1915. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I. London: Heinemann. OCLC 464479053.

- Broadbent, Harvey (2005). Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore. Camberwell, VIC: Viking/Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-04085-8.

- Carlyon, Les (2001). Gallipoli. Sydney: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7329-1089-1.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1920]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (repr. Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 978-1-84342-489-5. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009a) [1929]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (2nd, Imperial War Museum and Naval & military Press repr. ed.). London: Longmans, Green & Co. ISBN 978-1-84342-490-1. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009b) [1923]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. III (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 978-1-84342-491-8. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2013). Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-36220-9.

- Fewster, Kevin; Basarin, Vecihi; Basarin, Hatice Hurmuz (2003) [1985]. Gallipoli: The Turkish Story. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-045-3.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2004) [1991]. Gallipoli 1915: Frontal Assault on Turkey. Campaign Series. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-275-98288-1.

- Holmes, Richard, ed. (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866209-9.

- Howard, Michael (2002). The First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285362-2.

- Jenkins, R. (2001). Churchill. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-78290-3.

- Keegan, John (1998). The First World War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6645-9.

- Keyes, R. (1934). The Naval Memoirs of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes: The Narrow Seas to the Dardanelles, 1910–1915 (online scan ed.). London: T. Butterworth. OCLC 2366061. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1965). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919: The War Years to the eve of Jutland, 1914–1916. Vol. II. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 865180297.

- Morgenthau, Henry (1918). "XVIII: The Allied Armada Sails Away, Though on the Brink of Victory". Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page. OCLC 1173400. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- O'Connell, John (2010). Submarine Operational Effectiveness in the 20th Century (1900–1939) Part One. New York: Universe. ISBN 978-1-4502-3689-8.

- Ōzakman, Turgut (2008). Diriliş, Çanakkale 1915 [Resurrection, Canakkale 1915]. Ankara: Bilgi Yayınevi. ISBN 978-975-22-0247-4.

- Strachan, Hew (2003) [2001]. The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Tauber, Eliezer (1993). The Arab Movements in World War I. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-4083-9.

- Travers, Tim (2001). Gallipoli 1915. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2551-1.

Journals

- Layman, Richard D. (1987). "HMS Ark Royal 1914–1922". Cross and Cockade. 18 (4). ISSN 1360-9009.

Websites

- "Australia's Naval Gallipoli Hero [no date]" (PDF). Heritage Council of NSW. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

Further reading

- Jose, Arthur (1941) [1928]. "Chapter 9, Service Overseas, East Africa, Dardanelles, North Atlantic" (PDF). The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. IX (9th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 271462423. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Massie, R. K. (2005) [2004]. Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (pbk. Pimlico Random House ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-1-84413-411-3.

- Muhterem, Saral; Orhon, Alpaslan (1993). Çanakkale Cephesi Harekâte, 1 Nci Kitap, Haziran 1914 – 25 Nisan 1915 [Operations on the Dardanelles/Gallipoli Front, June 1914 – 25 April 1915 Book 1]. Birinci Dünya Harbi'nde Türk Harbi/Turkish Battles in the First World War. Vol. V. Ankara: TC Genelkurmay Başkanliği/General Staff Printing House. OCLC 863356254.

- Nykiel, Piotr (2001). Was it possible to renew the naval attack on the Dardanelles successfully the day after the 18th March? (Report). Çanakkale: The Gallipoli Campaign International Perspectives 85 Years On Conference Papers (24–25 April 2000).

External links

- Bibliography: Turkey in the First World War[permanent dead link]

- War in the Dardanelles: 1915

- Ottoman Naval Official History

- Account of the battle Archived 21 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine from the Imperial War Museum website (accessed Nov 2006)

- Winston Churchill & Gallipoli – UK Parliament Living Heritage