Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

| |

| Tournament information | |

|---|---|

| Location | Augusta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Established | 1934 |

| Course(s) | Augusta National Golf Club |

| Par | 72 |

| Length | 7,555 yards (6,908 m)[1] |

| Organized by | Augusta National Golf Club |

| Tour(s) | PGA Tour European Tour Japan Golf Tour |

| Format | Stroke play |

| Prize fund | US$20,000,000 |

| Month played | April[a] |

| Tournament record score | |

| Aggregate | 268 Dustin Johnson (2020) |

| To par | −20 as above |

| Current champion | |

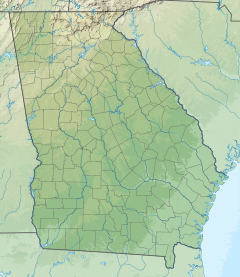

| Location map | |

Location in Georgia | |

The Masters Tournament (usually referred to as simply the Masters, or as the U.S. Masters outside North America)[2][3] is one of the four men's major golf championships in professional golf. Scheduled for the first full week in April, the Masters is the first major golf tournament of the year. Unlike the other major tournaments, the Masters is always held at the same location: Augusta National Golf Club, a private course in the city of Augusta, Georgia.

Amateur golf champion Bobby Jones and investment banker Clifford Roberts founded the Masters Tournament.[4] After his grand slam in 1930, Jones acquired the former plant nursery and co-designed Augusta National with course architect Alister MacKenzie.[1] First played in 1934, the Masters is an official money event[clarification needed] on the PGA Tour, the European Tour, and the Japan Golf Tour. The field of players is smaller than those of the other major championships because it is an invitational event, held by the Augusta National Golf Club.

The tournament has a number of traditions. Since the 1949 Masters, a green jacket has been awarded to the champion, who must return it to the clubhouse one year after his victory, although it remains his personal property and is stored with other champions' jackets in a specially designated cloakroom. In most instances, only a first-time and currently reigning champion may remove his jacket from the club grounds. A golfer who wins the event multiple times uses the same green jacket awarded upon his initial win unless he needs to be re-fitted with a new jacket.[5] The Champions Dinner, inaugurated by Ben Hogan at the 1952 Masters Tournament, is held on the Tuesday before each Masters and is open only to past champions and certain board members of the Augusta National Golf Club. Beginning in 1963, distinguished golfers, usually past champions, have hit an honorary tee shot on the morning of the first round to commence play. These have included Fred McLeod, Jock Hutchinson, Gene Sarazen, Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player, Lee Elder, and Tom Watson. Since 1960, a semi-social contest on the par-3 course has been played on Wednesday, the day before the first round.

Nicklaus has the most Masters wins, with six between 1963 and 1986. Tiger Woods won five between 1997 and 2019. Palmer won four between 1958 and 1964. Five have won three titles at Augusta: Jimmy Demaret, Sam Snead, Gary Player, Nick Faldo, and Phil Mickelson. Gary Player, from South Africa, was the first non-American player to win the tournament, in 1961; the second was Seve Ballesteros of Spain, the champion in 1980 and 1983.

The Augusta National course first opened in 1933 and has been modified many times by different architects. Among the changes: greens have been reshaped and, on occasion, entirely re-designed, bunkers have been added, water hazards have been extended, new tee boxes have been built, hundreds of trees have been planted, and several mounds have been installed.[6]

History

Augusta National Golf Club

The idea for Augusta National originated with Bobby Jones, who wanted to build a golf course after his retirement from the game. He sought advice from Clifford Roberts, who later became the chairman of the club. They came across a piece of land in Augusta, Georgia, of which Jones said: "Perfect! And to think this ground has been lying here all these years waiting for someone to come along and lay a golf course upon it."[7] The land had been an indigo plantation in the early nineteenth century and a plant nursery since 1857.[8] Jones hired Alister MacKenzie to help design the course, and work began in 1931. The course formally opened in 1933, but MacKenzie died before the first Masters Tournament was played.[9]

Early tournament years

The first "Augusta National Invitation Tournament", as the Masters was originally known, began on March 22, 1934, and was won by Horton Smith, who took the first prize of $1,500. The present name was adopted in 1939. The first tournament was played with current holes 10 through 18 played as the first nine, and 1 through 9 as the second nine[10] then reversed permanently to its present layout for the 1935 tournament.[4]

Initially the Augusta National Invitation field was composed of Bobby Jones' close associates. Jones had petitioned the USGA to hold the U.S. Open at Augusta but the USGA denied the petition, noting that the hot Georgia summers would create difficult playing conditions.[11]

Gene Sarazen hit the "shot heard 'round the world" in 1935, holing a shot from the fairway on the par 5 15th for a double eagle (albatross).[12] This tied Sarazen with Craig Wood, and in the ensuing 36-hole playoff, Sarazen was the victor by five strokes.[13]

Byron Nelson won the first of two Masters titles in 1937. Jimmy Demaret won three times as did Sam Snead in the 1940s and 1950s. Ben Hogan won the 1951 and 1953 Masters and was runner-up on four occasions.

In 1940, Clifford Roberts, chairman of the Masters, stated that the Masters was one of the top tournaments in the United States, if not the biggest. He stated, "I am told that the Masters has outdistanced in attendance both the U.S. Amateur and the PGA."[14] The tournament was not played from 1943 to 1945, due to World War II. To assist the war effort, cattle and turkeys were raised on the Augusta National grounds.[4]

1960s–1970s

The Big Three of Arnold Palmer, Gary Player, and Jack Nicklaus dominated the Masters from 1960 through 1978, winning the event 11 times between them during that span. After winning by one stroke in 1958,[13] Palmer won by one stroke again in 1960 in memorable circumstances. Trailing Ken Venturi by one shot in the 1960 event, Palmer made birdies on the last two holes to prevail. Palmer would go on to win another two Masters in 1962 and 1964.[13]

Nicklaus emerged in the early 1960s and served as a rival to the popular Palmer. Nicklaus won his first green jacket in 1963, defeating Tony Lema by one stroke.[15] Two years later, he shot a then-course record of 271 (17 under par) for his second Masters win, leading Bobby Jones to say that Nicklaus played "a game with which I am not familiar."[16] The next year, Nicklaus won his third green jacket in a grueling 18-hole playoff against Tommy Jacobs and Gay Brewer.[17] This made Nicklaus the first player to win consecutive Masters. He won again in 1972 by three strokes.[13] In 1975, Nicklaus won by one stroke in a close contest with Tom Weiskopf and Johnny Miller in one of the most exciting Masters to date.[18]

Player became the first non-American to win the Masters in 1961, beating Palmer, the defending champion, by one stroke when Palmer double-bogeyed the final hole.[13] In 1974, he won again by two strokes.[13] After not winning a tournament on the U.S. PGA tour for nearly four years, and at the age of 42, Player won his third and final Masters in 1978 by one stroke over three players.[13] Player is currently second in consecutive cuts made with 23 straight (tied with Fred Couples), and has played in a record 52 Masters.[19][20]

A controversial ending to the Masters occurred in 1968. Argentine champion Roberto De Vicenzo signed his scorecard (attested by playing partner Tommy Aaron) incorrectly recording him as making a par 4 instead of a birdie 3 on the 17th hole of the final round. According to the rules of golf, if a player signs a scorecard (thereby attesting to its veracity) that records a score on a hole higher than what he actually made on the hole, the player receives the higher score for that hole. This extra stroke cost De Vicenzo a chance to be in an 18-hole Monday playoff with Bob Goalby, who won the green jacket. De Vicenzo's mistake led to the famous quote, "What a stupid I am."[13][21]

In 1975, Lee Elder became the first African American to play in the Masters,[22] doing so 15 years before Augusta National admitted its first black member, Ron Townsend, as a result of the Shoal Creek Controversy.[23]

1980s–2000s

Non-Americans collected 11 victories in 20 years in the 1980s and 1990s, by far the strongest run they have had in any of the three majors played in the United States since the early days of the U.S. Open. The first European to win the Masters was Seve Ballesteros in 1980. Nicklaus became the oldest player to win the Masters in 1986 when he won for the sixth time at age 46.[13][24]

During this period, no golfer suffered more disappointment at the Masters than Greg Norman. In his first appearance at Augusta in 1981, he led during the second nine but ended up finishing fourth. In 1986, after birdieing holes 14 through 17 to tie Nicklaus for the lead, he badly pushed his 4-iron approach on 18 into the patrons surrounding the green and missed his par putt for a closing bogey. In 1987, Norman lost a sudden-death playoff when Larry Mize holed out a remarkable 45-yard pitch shot to birdie the second playoff hole. Mize thus became the first Augusta native to win the Masters.[25] In 1996, Norman tied the course record with an opening-round 63 and had a six-stroke lead over Nick Faldo entering the final round. However, he stumbled to a closing 78 while Faldo, his playing partner that day, carded a 67 to win by five shots for his third Masters championship.[26] Norman also led the 1999 Masters on the second nine of the final round, only to falter again and finish third behind winner José María Olazábal, who won his second green jacket. Norman finished in the top five at the Masters eight times, but never won.

Two-time champion Ben Crenshaw captured an emotional Masters win in 1995, just days after the death of his lifelong teacher and mentor Harvey Penick. After making his final putt to win, he broke down sobbing at the hole and was consoled and embraced by his caddie. In the post-tournament interview, Crenshaw said: "I had a 15th club in my bag," a reference to Penick. (The "15th club" reference is based on the golf rule that limits a player to carrying 14 clubs during a round.) Crenshaw first won at Augusta in 1984.

In 1997, 21-year-old Tiger Woods became the youngest champion in Masters history, winning by 12 shots with an 18-under par 270 which broke the 72-hole record that had stood for 32 years.[4] In 2001, Woods completed his "Tiger Slam" by winning his fourth straight major championship at the Masters by two shots over David Duval.[13] He won again the following year, making him only the third player in history (after Nicklaus and Faldo) to win the tournament in consecutive years,[13] as well as in 2005 when he defeated Chris DiMarco in a playoff for his first major championship win in almost three years.[13]

In 2003, the Augusta National Golf Club was targeted by Martha Burk, who organized a failed protest at that year's Masters to pressure the club into accepting female members. Burk planned to protest at the front gates of Augusta National during the third day of the tournament, but her application for a permit to do so was denied.[27] A court appeal was dismissed.[28] In 2004, Burk stated that she had no further plans to protest against the club.[29] The club admitted its first two women members, Condoleezza Rice and Darla Moore, in 2012.

Augusta National chairman Billy Payne himself made headlines in April 2010 when he commented at the annual pre-Masters press conference on Tiger Woods' off-the-course behavior. "It's not simply the degree of his conduct that is so egregious here," Payne said, in his opening speech. "It is the fact he disappointed all of us and more importantly our kids and grandkids."[30][31][32]

In 2003, Mike Weir became the first Canadian to win a men's major championship and the first left-hander to win the Masters when he defeated Len Mattiace in a playoff.[13] The following year another left-hander, Phil Mickelson, won his first major championship by making a birdie on the final hole to beat Ernie Els by a stroke.[13] Mickelson also won the tournament in 2006 and 2010. In 2011, unheralded South African Charl Schwartzel birdied the final four holes to win by two strokes. In 2012, Bubba Watson won the tournament on the second playoff hole over Louis Oosthuizen. In 2013 Adam Scott won the Masters in a playoff over 2009 champion Ángel Cabrera, making him the first Australian to win the tournament.[33] Watson won the 2014 Masters by three strokes over Jordan Spieth and Jonas Blixt, his second Masters title in three years and the sixth for a left-hander in 12 years. In 2015, Spieth would become the second-youngest winner (behind Woods) in just his second Masters, equaling Woods' 72-hole scoring record.[34] In 2017, Sergio García beat Justin Rose in a playoff for his long-awaited first major title. In 2019, Tiger Woods captured his fifth Masters, his first win at Augusta National in 14 years and his first major title since 2008.

The 2020 Masters Tournament, originally scheduled to be played April 9–12, was postponed until November due to the ongoing coronavirus outbreak.[35] Dustin Johnson won the tournament by five strokes.

Traditions

Awards

The total prize money for the 2024 Masters Tournament was $20,000,000, with $3,600,000 going to the winner. In the inaugural year of 1934, the winner Horton Smith received $1,500 out of a $5,000 purse.[36] After Nicklaus's first win in 1963, he received $20,000, while after his final victory in 1986 he won $144,000.[37][38] In recent years the purse has grown quickly. Between 2001 and 2014, the winner's share grew by $612,000, and the purse grew by $3,400,000.[39][36][40]

Green jacket

In addition to a cash prize, the winner of the tournament is presented with a distinctive green jacket, formally awarded since 1949 and informally awarded to the champions from the years prior. The green sport coat is the official attire worn by members of Augusta National while on the club grounds; each Masters winner becomes an honorary member of the club. The recipient of the green jacket has it presented to him inside the Butler Cabin soon after the end of the tournament in a televised ceremony, and the presentation is then repeated outside near the 18th green in front of the patrons. Winners keep their jacket for the year after their victory, then return it to the club to wear whenever they are present on the club grounds. Sam Snead was the first Masters champion to be awarded the green jacket after he took his first Masters title in 1949.

The green jacket is only allowed to be removed from the Augusta National grounds by the reigning champion, after which it must remain at the club. Exceptions to this rule include Gary Player, who in his joy of winning mistakenly took his jacket home to South Africa after his 1961 victory (although he has always followed the spirit of the rule and has never worn the jacket);[41] Seve Ballesteros who, in an interview with Peter Alliss from his home in Pedreña, showed one of his two green jackets in his trophy room; and Henry Picard, whose jacket was removed from the club before the tradition was well established, remained in his closet for a number of years, and is now on display at Canterbury Golf Club in Beachwood, Ohio, where he was the club professional for many years.[42][43]

By tradition, the winner of the previous year's Masters Tournament puts the jacket on the current winner at the end of the tournament. In 1966, Jack Nicklaus became the first player to win in consecutive years and he donned the jacket himself.[17] When Nick Faldo (in 1990) and Tiger Woods (in 2002) repeated as champions, the chairman of Augusta National put the jacket on them.

In addition to the green jacket, winners of the tournament receive a gold medal. In 2017, a green jacket that was found at a thrift store in 1994 was sold at auction for $139,000.[44]

There are several awards presented to players who perform exceptional feats during the tournament. The player who has the daily lowest score receives a crystal vase, while players who score a hole-in-one or a double eagle win a large crystal bowl.[45] For each eagle a player makes, they receive a pair of crystal goblets.

Trophies

Winners also have their names engraved on the actual silver Masters trophy. The runner-up receives a silver medal, introduced in 1951. Beginning in 1978, a silver salver was added as an award for the runner-up.[4]

In 1952, the Masters began presenting an award, known as the Silver Cup, to the lowest scoring amateur to make the cut. In 1954, they began presenting an amateur silver medal to the low amateur runner-up.[4]

The original trophy weighs over 130 pounds and sits on a four-foot-wide base. It resides permanently at Augusta National and depicts the clubhouse of the classic course. Winners instead receive a replica, which is significantly smaller, stands just 6.5 inches tall and weighs 20 pounds, which they get to keep. The champion and the runner-up both have their names engraved on the permanent trophy, solidifying themselves in golf history.[46]

The Double Eagle trophy was introduced in 1967 when Bruce Devlin holed out for double eagle on number 8. He was only the second to do so, and the first in 32 years, following Gene Sarazen on hole 15 in 1932. The trophy is a large crystal bowl with "Masters Tournament" engraved around the top.[47]

Pre-tournament events

In 2013, Augusta National partnered with the USGA and the PGA of America to establish Drive, Chip and Putt, a youth golf skills competition which was first held in 2014. The event was established as part of an effort to help promote the sport of golf among youth; the winners of local qualifiers in different age groups advance to the national finals, which have been held at Augusta National on the Sunday immediately preceding the Masters. The driving and chipping portions of the event are held on the course's practice range, and the putting portion has been played on the 18th hole.[48][49][50]

On April 4, 2018, prior to the 2018 tournament, new Augusta National chairman Fred Ridley announced that the club would host the Augusta National Women's Amateur beginning in 2019. The first two rounds will be held at the Champion's Retreat club in Evans, Georgia, with the final two rounds hosted by Augusta National (the final round will take place on the Saturday directly preceding the tournament). Ridley stated that holding such an event at Augusta National would have the "greatest impact" on women's golf. Although concerns were raised that the event would conflict with the LPGA Tour's ANA Inspiration (which has invited top amateur players to compete), Ridley stated that he had discussed the event with commissioner Mike Whan, and stated that he agreed on the notion that any move to bolster the prominence of women's golf would be a "win" for the LPGA over time. The winner of the Augusta National Women's Amateur is exempt from two women's golf majors.[51][52]

Par-3 contest

The Par-3 contest was first introduced in 1960, and was won that year by Snead. Since then it has traditionally been played on the Wednesday before the tournament starts. The par 3 course was built in 1958. It is a nine-hole course, with a par of 27, and measures 1,060 yards (970 m) in length.[53]

There have been 94 holes-in-one in the history of the contest, with a record nine occurring in 2016, during which Rickie Fowler and Justin Thomas scored back-to-back holes in one on the 4th hole, while playing in a group with reigning champion Jordan Spieth.[54][55] Camilo Villegas became the first player to card two holes-in-one in the same round during the 2015 Par 3 Contest. This achievement was duplicated by Séamus Power, who scored back-to-back holes in one on holes 8 and 9 during the 2023 par 3 contest.[56] No par 3 contest winner has also won the Masters in the same year.[57][58] There have been several repeat winners, including Pádraig Harrington, Sandy Lyle, Sam Snead, and Tom Watson. The former two won in successive years.

In this event, golfers may use their children as caddies, which helps to create a family-friendly atmosphere. In 2008, the event was televised for the first time by ESPN.

The winner of the par 3 competition, which is played the day before the tournament begins, wins a crystal bowl.[59]

Player invitations

As with the other majors, winning the Masters gives a golfer several privileges which make his career more secure. Masters champions are automatically invited to play in the other three majors (the U.S. Open, The Open Championship, and the PGA Championship) for the next five years (except for amateur winners, unless they turn pro within the five-year period), and earn a lifetime invitation to the Masters. They also receive membership on the PGA Tour for the following five seasons and invitations to The Players Championship for five years.[60]

Because the tournament was established by an amateur champion, Bobby Jones, the Masters has a tradition of honoring amateur golf. It invites winners of the most prestigious amateur tournaments in the world. Also, the current U.S. Amateur champion always plays in the same group as the defending Masters champion for the first two days of the tournament.

Amateurs in the field are welcome to stay in the "Crow's Nest" atop the Augusta National clubhouse during the tournament. The Crow's Nest is 1,200 square feet (110 m2) with lodging space for five during the competition.

Opening tee shot

Since 1963, the custom in most years has been to start the tournament with an honorary opening tee shot at the first hole,[61] typically by one or more legendary players. For a number of years before 1963, Jock Hutchison and Fred McLeod had been the first pair to tee off, both being able to play as past major championship winners. However, in 1963 the eligibility rules were changed and they were no longer able to compete. The idea of honorary starters was introduced with Hutchison and McLeod being the first two. This twosome led off every tournament from 1963 until 1973 when poor health prevented Hutchison from swinging a club. McLeod continued on until his death in 1976. Byron Nelson and Gene Sarazen started in 1981 and were then joined by Sam Snead in 1984. This trio continued until 1999 when Sarazen died, while Nelson stopped in 2001. Snead hit his final opening tee shot in 2002, a little over a month before he died.

In 2007, Arnold Palmer took over as the honorary starter. Palmer also had the honor in 2008 and 2009.[62] At the 2010 and 2011 Masters Tournaments, Jack Nicklaus joined Palmer as an honorary co-starter for the event.[63] In 2012, Gary Player joined them. Palmer announced in March 2016 that a lingering shoulder issue would prevent him from partaking in the 2016 tee shot.[64] Palmer was still in attendance for the ceremony.[65]

Following Palmer's death in 2016, the 2017 ceremony featured tributes; his green jacket was draped over an empty white chair, while everyone in attendance wore "Arnie's Army" badges.[66][67]

In 2021 Lee Elder joined Nicklaus and Player as an honorary starter. He was invited to join them as he was the first African-American to take part in the Masters in 1975. Despite bad health preventing Elder from hitting a shot, he was still present and received a standing ovation from the crowd.

Two-time Masters champion Tom Watson joined Nicklaus and Player, starting in 2022.[68]

Food

Champions' Dinner

The Champions' Dinner is held each year on the Tuesday evening preceding Thursday's first round. The dinner was first held in 1952, hosted by defending champion Ben Hogan, to honor the past champions of the tournament.[69] At that time 15 tournaments had been played, and the number of past champions was 11. Officially known as the "Masters Club", it includes only past winners of the Masters, although selected members of the Augusta National Golf Club have been included as honorary members, usually the chairman.

The defending champion, as host, selects the menu for the dinner. Frequently, Masters champions have served cuisine from their home regions prepared by the Masters chef. Notable examples have included haggis, served by Scotsman Sandy Lyle in 1989,[70] and bobotie, a South African dish, served at the behest of 2008 champion Trevor Immelman. Other examples include German Bernhard Langer's 1986 Wiener schnitzel, Britain's Nick Faldo's fish and chips, Canadian Mike Weir's elk and wild boar, and Vijay Singh's seafood tom kah and chicken panang curry. The 2011 dinner of Phil Mickelson was a Spanish-themed menu in hopes that Seve Ballesteros would attend, but he was too sick to attend and died weeks later.[71]

In 1998, Tiger Woods served cheeseburgers, chicken sandwiches, french fries and milkshakes. Woods was the youngest winner, and when asked about his food choices, he responded with "They said you could pick anything you want... Hey, it's part of being young, that's what I eat."[72] Fuzzy Zoeller, the 1979 champion, created a media storm when he suggested that Woods refrain from serving collard greens and fried chicken, dishes commonly associated with African-American culture.[73]

Pimento cheese sandwiches

Pimento cheese sandwiches have a long history at the Masters.[74][75] They have been served as a concession since the 1940s.[76][77] Minor controversy ensued in 2013 when the club switched food suppliers for the Masters and the new supplier was unable to duplicate the recipe used by the previous supplier, resulting in a sandwich with a markedly different taste.[78] Southern Living and Golf Digest called the sandwich "iconic" of the tournament.[79][80] Sports Illustrated called the sandwich "legendary" and "more than a food option – it’s a representation of the sport's history and its traditions".[77]

Caddies

Until 1983, all players in the Masters were required to use the services of an Augusta National Club caddie,[81][82][83] who by club tradition was always an African-American man.[23] Club co-founder Clifford Roberts is reputed to have said, "As long as I'm alive, golfers will be white, and caddies will be black."[84] Since 1983—six years after Roberts's death in 1977—players have been allowed the option of bringing their own caddie to the tournament.

The Masters requires caddies to wear a uniform consisting of a white jumpsuit, a green Masters cap, and white tennis shoes. The surname, and sometimes first initial, of each player is found on the back of his caddie's uniform. The defending champion always receives caddie number "1": other golfers get their caddie numbers from the order in which they register for the tournament. The other majors and some PGA Tour events formerly had a similar policy concerning caddies well into the 1970s;[85][86][87] the U.S. Open first allowed players to use their own caddies in 1976.[88][89]

No phone policy

Fans who do obtain Master tickets (badges) have to follow a strict no cell phone policy while on the property of Augusta National.

Format

The Masters is the first major championship of the year. Since 1948, its final round has been scheduled for the second Sunday of April, with several exceptions. It ended on the first Sunday four times (1952, 1957, 1958, 1959) and the 1979 and 1984 tournaments ended on April 15, the month's third Sunday.[4] The first edition in 1934 was held in late March and the next ten were in early April, with only the 1942 event scheduled to end on the second Sunday. The 2020 event, postponed by the COVID-19 pandemic, was held from November 12 to 15, thus being the last major of the year.

Similar to the other majors, the tournament consists of four rounds at 18 holes each, Thursday through Sunday (when there are no delays). The Masters has a relatively small field of contenders when compared with other golf tournaments, so the competitors play in groups of three for the first two rounds (36 holes) and the field is not split to start on the 1st and 10th tees unless weather shortens the available playing time. The tournament is unique in that it is the only major tournament conducted by a private club rather than a national golf organization like the PGA.[6]

Originally, the Masters was the only tournament to use two-man pairings during the first two rounds. It was also the only event to re-pair based on the leaderboard before Friday's round, as most tournaments only do this on the weekend. This practice ended in the early 2000s when the Masters switched to the more standard three-man groups and the groups are now kept intact on Friday, with players sharing the same playing partners in both of the first two rounds.[citation needed]

After 36 holes of play, a cut-off score is calculated to reduce the size of the field for the weekend rounds. In 2020, to "make the cut", players must be in the top 50 places (ties counting).[90] Before 1957, there was no 36-hole cut and all of the invitees played four rounds, if desired. From 1957 to 1961, the top 40 scores (including ties) made the cut. From 1962 to 2012, it was the top 44 (and ties) or within 10 strokes of the lead.[20] From 2013 to 2019, it was the top 50 (and ties) or within 10 strokes of the lead.[91]

Following the cut, an additional 36 holes are played over the final two days. Should the fourth round fail to produce a winner, all players tied for the lead enter a sudden-death playoff. Play begins on the 18th hole, followed by the adjacent 10th, repeating until one player remains. Adopted in 1976, the sudden-death playoff was originally formatted to start on the first hole,[92] but was not needed for the first three years. It was changed for 1979 to the inward (final) nine holes, starting at the tenth tee, where the television coverage began.[93] First employed that same year, the Masters' first sudden-death playoff, won by Fuzzy Zoeller, ended on the 11th green. The current arrangement, beginning at the 18th tee, was amended for 2004 and first used the following year. Through 2017, the eleven sudden-death playoffs have yet to advance past the second extra hole. Earlier playoffs were 18 holes on the following day, except for the first in 1935, which was 36 holes (Gene Sarazen defeated Craig Wood); the last 18-hole playoff was in 1970 when Billy Casper defeated Gene Littler, and none of the full-round playoffs went to additional holes.

Course

The golf course was formerly a plant nursery and each hole is named after the tree or shrub with which it has become associated.[8]

The course layout in 2024:

| Hole | Name | Yards | Par | Hole | Name | Yards | Par | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tea Olive | 445 | 4 | 10 | Camellia | 495 | 4 | |

| 2 | Pink Dogwood | 585 | 5 | 11 | White Dogwood | 520 | 4 | |

| 3 | Flowering Peach | 350 | 4 | 12 | Golden Bell | 155 | 3 | |

| 4 | Flowering Crab Apple | 240 | 3 | 13 | Azalea | 545 | 5 | |

| 5 | Magnolia | 495 | 4 | 14 | Chinese Fir | 440 | 4 | |

| 6 | Juniper | 180 | 3 | 15 | Firethorn | 550 | 5 | |

| 7 | Pampas | 450 | 4 | 16 | Redbud | 170 | 3 | |

| 8 | Yellow Jasmine | 570 | 5 | 17 | Nandina | 440 | 4 | |

| 9 | Carolina Cherry | 460 | 4 | 18 | Holly | 465 | 4 | |

| Out | 3,775 | 36 | In | 3,780 | 36 | |||

| Source:[1][94] | Total | 7,555 | 72 | |||||

Lengths of the course for the Masters at the start of each decade:

Course adjustments

As with many other courses, Augusta National's championship setup was lengthened in recent years. In 2001, the course measured 6,925 yards (6,332 m) and was extended to 7,270 yards (6,648 m) for 2002, and again in 2006 to 7,445 yards (6,808 m); 520 yards (475 m) longer than the 2001 course.[95][96] The changes attracted many critics, including the most successful players in Masters history, Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Tiger Woods. Woods claimed that the "shorter hitters are going to struggle". Augusta National chairman Hootie Johnson was unperturbed, stating, "We are comfortable with what we are doing with the golf course." After a practice round, Gary Player defended the changes, saying, "There have been a lot of criticisms, but I think unjustly so, now I've played it.... The guys are basically having to hit the same second shots that Jack Nicklaus had to hit (in his prime)".[97]

The first hole was shortened by 10 yards (9 m) for the 2009 Masters Tournament. For the 2019 Masters Tournament, the fifth hole was lengthened by 40 yards (37 m) from 455 yards to 495 yards, with two new gaping bunkers on the left side of the fairway.[98] The current length of the course is 7,475 yards (6,835 m).

Originally, the grass on the putting greens was wide-bladed Bermuda. The greens lost speed, especially during the late 1970s, after the introduction of a healthier strain of narrow-bladed Bermuda, which thrived and grew thicker. In 1978, the greens on the par 3 course were reconstructed with bentgrass, a narrow-bladed species that could be mowed shorter, eliminating grain.[99] After this test run, the greens on the main course were replaced with bentgrass in time for the 1981 Masters. The bentgrass resulted in significantly faster putting surfaces, which has required a reduction in some of the contours of the greens over time.[99]

Just before the 1975 tournament, the common beige sand in the bunkers was replaced with the now-signature white feldspar. It is a quartz derivative of the mining of feldspar and is shipped in from North Carolina.[100]

Field

The Masters has the smallest field of the major championships, with 85–100 players. Unlike other majors, there are no alternates or qualifying tournaments. It is an invitational event, with invitations largely issued on an automatic basis to players who meet published criteria. The top 50 players in the Official World Golf Ranking are all invited.[101]

Past champions are always eligible, but since 2002 the Augusta National Golf Club has discouraged them from continuing to participate at an advanced age. Some will later become honorary starters.[102]

Invitation categories (from 2024)

- See footnote.[103]

- Note: Categories 7–12 are honored only if the participants maintain their amateur status prior to the tournament.

- Masters Tournament Champions (lifetime)

- U.S. Open champions (five years)

- The Open champions (five years)

- PGA champions (five years)

- Winners of the Players Championship (three years)

- Current Olympic Gold Medalist (one year)

- Current U.S. Amateur champion and runner-up

- Current British Amateur champion

- Current Asia-Pacific Amateur champion

- Current Latin America Amateur champion

- Current U.S. Mid-Amateur champion

- Current NCAA Division I Men's Golf Championship individual champion

- The first 12 players, including ties, in the previous year's Masters Tournament

- The first 4 players, including ties, in the previous year's U.S. Open

- The first 4 players, including ties, in the previous year's Open Championship

- The first 4 players, including ties, in the previous year's PGA Championship

- Winners of PGA Tour events that award at least a full-point allocation for the FedEx Cup, from one Masters Tournament to the next

- Those qualifying and eligible for the previous year's season-ending Tour Championship (top 30 in FedEx Cup prior to tournament)

- The 50 leaders on the final Official World Golf Ranking for the previous calendar year

- The 50 leaders on the Official World Golf Ranking published during the week prior to the current Masters Tournament

Most of the top current players will meet the criteria of multiple categories for invitation. The Masters Committee, at its discretion, can also invite any golfer not otherwise qualified, although in practice these invitations are mostly reserved for international players.[104]

Changes since 2014

Changes for the 2014 tournament include invitations now being awarded to the autumn events in the PGA Tour, which now begin the wraparound season, tightening of qualifications (top 12 plus ties from the Masters, top 4 from the U.S. Open, Open Championship, and PGA Championship), and the top 30 on the PGA Tour now referencing the season-ending points before the Tour Championship, not the former annual money list.[91] The 2015 Masters added the winner of the newly established Latin America Amateur Championship, which effectively replaced the exemption for the U.S. Amateur Public Links, which ended after the 2014 tournament. (The final Public Links champion played in the 2015 Masters.)[105]

Prior to the start of the 2023 Masters Tournament, several changes to the criteria were announced to come into effect from 2024. An additional criterion was added for amateur golfers, for the reigning individual champion of the NCAA Division I Men's Golf Championship,[106] and PGA Tour criteria were modified to account for scheduling changes (previously only regular season and playoff events were included) and to clarify that players must remain eligible for the Tour Championship.[107][108]

Most wins

The first winner of the Masters Tournament was Horton Smith in 1934, and he repeated in 1936. The player with the most Masters victories is Jack Nicklaus, who won six times between 1963 and 1986. Tiger Woods has five wins, followed by Arnold Palmer with four, and Jimmy Demaret, Gary Player, Sam Snead, Nick Faldo, and Phil Mickelson have three titles to their name. Player was the tournament's first overseas winner with his first victory in 1961. Two-time champions include Byron Nelson, Ben Hogan, Tom Watson, Seve Ballesteros, Bernhard Langer, Ben Crenshaw, José María Olazábal, Bubba Watson, and Scottie Scheffler.[109]

Winners

- In the "Runner(s)-up" column, the names are sorted alphabetically, based on the last name of that year's runner(s)-up.

- The sudden-death format was adopted in 1976, first used in 1979, and revised in 2004.[110]

- None of the 11 sudden-death playoffs has advanced past the second hole; four were decided at the first hole, seven at the second.

- Playoffs prior to 1976 were full 18-hole rounds, except for 1935, which was 36 holes.

- None of the 6 full-round playoffs were tied at the end of the round; the closest margin was one stroke in 1942 and 1954.

- The 1962 playoff included three players: Arnold Palmer (68), Gary Player (71), and Dow Finsterwald (77).

- The 1966 playoff included three players: Jack Nicklaus (70), Tommy Jacobs (72), and Gay Brewer (78).

Low amateurs

In 1952, the Masters began presenting an award, known as the Silver Cup, to the lowest-scoring amateur to make the cut. In 1954 they began presenting an amateur silver medal to the low amateur runner-up. There have been seven players to win low amateur and then go on to win the Masters as a professional. These players are Cary Middlecoff, Jack Nicklaus, Ben Crenshaw, Phil Mickelson, Tiger Woods, Sergio García, and Hideki Matsuyama.

Records

Jack Nicklaus has won the most Masters (six) and was 46 years, 82 days old when he won in 1986, making him the oldest winner of the Masters.[24] Nicklaus is the record holder for the most top tens, with 22, and the most cuts made, with 37.[20][111] The youngest winner of the Masters is Tiger Woods, who was 21 years, 104 days old when he won in 1997. In that year, Woods also broke the records for the widest winning margin (12 strokes), and the lowest winning score, with 270 (−18). Jordan Spieth tied his score record in 2015. Dustin Johnson broke the record in 2020 with a 268 (-20).[112]

In 2013, Guan Tianlang became the youngest player ever to compete in the Masters, at age 14 years, 168 days on the opening day of the tournament;[113] the following day, he became the youngest ever to make the cut at the Masters or any men's major championship.[114]

In 2020, Australian Cameron Smith became the first golfer in Masters history to shoot all four rounds in the 60s (67, 68, 69, 69). Finishing at 15 under par, en route to a tie for second-place finish with Sungjae Im.

Gary Player holds the record for most appearances, with 52. Tiger Woods holds the record for consecutive cuts made with 24 between 1997 and 2024; he did not compete in 2014, 2016, 2017, and 2021.[115] In 2023, Fred Couples became the oldest player to make the cut, doing so at age 63 years, 186 days.[116]

Nick Price and Greg Norman share the course record of 63, with their rounds coming in 1986 and 1996 respectively.

The highest winning score of 289 (+1) has occurred three times: Sam Snead in 1954, Jack Burke Jr. in 1956, and Zach Johnson in 2007. Anthony Kim holds the record for most birdies in a round with 11 in 2009 during his second round.[112]

There have been only four double eagles carded in the history of the Masters; the latest was by a contender in the fourth round in 2012. In the penultimate pairing with eventual champion Bubba Watson, Louis Oosthuizen's 260-yard (238 m) downhill 4 iron from the fairway made the left side of the green at the par-5 second hole, called Pink Dogwood, rolled downhill, and in.[117] The other two rare occurrences of this feat after Sarazen's double eagle on the fabled course's Fire Thorn hole in 1935: Bruce Devlin made double eagle from 248 yards (227 m) out with a 4-wood at the eighth hole (Yellow Jasmine) in the first round in 1967, while Jeff Maggert hit a 3-iron 222 yards (203 m) at the 13th hole (Azalea) in the fourth round in 1994.[118]

Three players share the record for most runner-up finishes with four – Ben Hogan (1942, 1946, 1954, 1955), Tom Weiskopf (1969, 1972, 1974, 1975), and Jack Nicklaus (1964, 1971, 1977, 1981). Nicklaus and Tiger Woods are the only golfers to have won the Masters in three separate decades.

The highest official score in a round was 95 by Charles Kunkle in 1956 and the highest unofficial score was 106 by Billy Casper in 1989 (he refused to hand in his scorecard to avoid holding the record).[119]

Broadcasting

United States television

| Network | Years of broadcast |

|---|---|

| CBS | 1956–present |

| USA Network | 1982–2007 |

| ESPN | 2008–present |

CBS has televised the Masters in the United States every year since 1956,[120] when it used six cameras and covered only the final four holes. Tournament coverage of the first eight holes did not begin until 1993 because of resistance from the tournament organizers, but by 2006, more than 50 cameras were used. Chairman Jack Stephens felt that the back nine was always more "compelling", increased coverage would increase the need for sponsorship spending, and that broadcasting the front nine of the course on television would cut down on attendance and television viewership for the tournament.[120][121][122] USA Network added first- and second-round coverage in 1982.[123] In 2008, ESPN replaced USA as broadcaster of early-round coverage. These broadcasts use the CBS Sports production staff and commentators, but with ESPN personality Scott Van Pelt (succeeding Mike Tirico, who replaced Bill Macatee's similar role under USA Network) as studio host, as well as Curtis Strange as studio analyst.[124][123][125] CBS carries two 15-minute highlight programs in late night covering the first and second rounds, which airs after their affiliates' late night local newscasts.

In 2005, CBS broadcast the tournament with high-definition fixed and handheld wired cameras, as well as standard-definition wireless handheld cameras. In 2006, a webstream called "Amen Corner Live" began providing coverage of all players passing through holes 11, 12, and 13 through all four rounds.[126] This was the first full tournament multi-hole webcast from a major championship. In 2007, CBS added "Masters Extra," an extra hour of full-field bonus coverage daily on the internet, preceding the television broadcasts. In 2008, CBS added full coverage of holes 15 and 16 live on the web. In 2011, "Masters Extra" was dropped after officials gave ESPN an extra hour each day on Thursday and Friday. In 2016, the Amen Corner feed was broadcast in 4K ultra high definition exclusively on DirecTV—as one of the first live U.S. sports telecasts in the format.[127][128] A second channel of 4K coverage covering holes 15 and 16 was added in 2017,[129] and this coverage was produced with high-dynamic-range (HDR) color in 2018.[130]

While Augusta National Golf Club has consistently chosen CBS as its U.S. broadcast partner, it has done so in successive one-year contracts.[131] Former CBS Sports president Neal Pilson stated that their relationship had gotten to the point where the contracts could be negotiated in just hours.[120] Due to the lack of long-term contractual security, as well as the club's limited dependence on broadcast rights fees (owing to its affluent membership), it is widely held that CBS allows Augusta National greater control over the content of the broadcast, or at least performs some form of self-censorship, in order to maintain future rights. The club, however, has insisted it does not make any demands with respect to the content of the broadcast.[132][133] Despite this, announcers who have been deemed not to have acted with the decorum expected by the club have been removed, notably Jack Whitaker and Gary McCord,[132] and there also tends to be a lack of discussion of any controversy involving Augusta National, such as the 2003 Martha Burk protests.[133]

The coverage itself carries a more formal style than other golf telecasts; announcers refer to the gallery as patrons rather than as spectators or fans. Gallery itself is also used.[134] The club also disallows promotions for other network programs, or other forms of sponsored features.[134] Significant restrictions have been placed on the tournament's broadcast hours compared to other major championships. Only in the 21st century did the tournament allow CBS to air 18-hole coverage of the leaders, a standard at the other three majors.[132] Since 1981, CBS has used "Augusta" by Dave Loggins as the event telecast's distinctive theme music. Loggins originally came up with the song during his first trip to the Augusta course in 1981.[135]

The club mandates minimal commercial interruption, currently limited to four minutes per hour (as opposed to the usual 12 or more); this is subsidized by selling exclusive sponsorship packages to two or three companies – currently these "global sponsors" are AT&T, IBM, and Mercedes-Benz.[134] AT&T (then SBC) and IBM have sponsored the tournament since 2005, joined at first by ExxonMobil, which in 2014 was replaced as a global sponsor by Mercedes-Benz.[136] In 2002, in the wake of calls to boycott tournament sponsors over the Martha Burk controversy, club chairman Hootie Johnson suspended all television sponsorship of the 2003 tournament. He argued that it was "unfair" to have the Masters' sponsors become involved with the controversy by means of association with the tournament, as their sponsorship is of the Masters and not Augusta National itself. CBS agreed to split production costs for the tournament with the club to make up for the lack of sponsorship. After the arrangement continued into 2004, the tournament reinstated sponsorships for 2005, with the new partners of ExxonMobil, IBM, and SBC.[137][138]

The club also sells separate sponsorship packages, which do not provide rights to air commercials on the U.S. telecasts, to two "international partners"; in 2014, those companies were Rolex and UPS (the latter of which replaced Mercedes-Benz upon that company's elevation to "global sponsor" status).[136]

Radio coverage

Westwood One (previously Dial Global and CBS Radio) has provided live radio play-by-play coverage in the United States since 1956. This coverage can also be heard on the official Masters website. The network provides short two- or three-minute updates throughout the tournament, as well as longer three- and four-hour segments towards the end of the day.[139]

International television

The first UK live coverage of the event was in 1984 when Channel 4 aired coverage of the closing moments of the 3rd and 4th rounds. Channel 4 repeated this level of coverage in 1985. The rights then transferred to the BBC which also initially only provided coverage of the 3rd and 4th rounds. With the 2007 launch of BBC HD, UK viewers were able to watch the championship in that format. BBC Sport held the exclusive TV and radio rights through to 2010.[140] The BBC's coverage airs without commercials because it is financed by a licence fee. From the 2011 Masters, Sky Sports began broadcasting all four days, as well as the par 3 contest in HD and, for the first time ever, in 3D. The BBC continued to air live coverage of the weekend rounds in parallel with Sky until 2019, when it was announced that Sky will hold exclusive rights to live coverage of all four rounds beginning 2020. The BBC will only hold rights to delayed highlights. With its loss of live rights to the Open Championship to Sky in 2016, it marks the first time since 1955 that the BBC no longer holds any rights to live professional golf.[141][142][143] although the Corporation continues to provide live radio commentary on BBC Radio 5 Live.

In Ireland, Setanta Ireland previously showed all four rounds, and now since 2017 Eir Sport broadcast all four rounds live having previously broadcast the opening two rounds with RTÉ broadcasting the weekend coverage.[144] After Eir Sport's closure in 2021, Sky Sports will broadcast the event exclusively in Ireland for the first time, like in the UK.[145]

In Canada, broadcast rights to the Masters are held by Bell Media, with coverage divided between TSN (cable), which carries live simulcasts and primetime encores of CBS and ESPN coverage for all four rounds, CTV (broadcast), which simulcasts CBS's coverage of the weekend rounds, and RDS, which carries French-language coverage. Prior to 2013, Canadian broadcast rights were held by a marketing company, Graham Sanborn Media,[146] which in turn bought time on the Global Television Network, TSN, and RDS (except for 2012 when French-language coverage aired on TVA and TVA Sports) to air the broadcasts, also selling all of the advertising for the Canadian broadcasts. This was an unusual arrangement in Canadian sports broadcasting, as in most cases broadcasters acquire their rights directly from the event organizers or through partnerships with international rightsholders, such as ESPN International (ESPN owns a minority stake in TSN). In 2013, Global and TSN began selling advertising directly, and co-produced supplemental programs covering the tournament (while still carrying U.S. coverage for the tournament itself).[147][148]

On December 15, 2015, TSN parent company Bell Media announced that it had acquired exclusive Canadian rights to the tournament beginning 2016 under a multi-year deal. Broadcast television coverage moved to co-owned broadcast network CTV, while TSN uses its expanded five-channel service to carry supplemental feeds (including the Amen Corner feed and early coverage of each round) that were previously exclusive to digital platforms.[149][150]

In France, the Masters is broadcast live on Canal+ and Canal+ Sport.

In 53 countries, including much of Latin America, broadcast rights for the entire tournament are held by the ESPN International networks.[151]

Ticketing

Although tickets (more commonly referred to as "badges") for the Masters are not expensive at face value, they are very difficult to come by. Masters tickets are considered the second-hardest to obtain in sports, trailing only the Super Bowl.[152] Even the practice rounds can be difficult to gain entrance into. Practice rounds and daily tournament tickets are sold in advance, through a selection process, only after receipt of an online application. All tickets are sold in advance and there are no tickets sold at the gates.[153] Additionally, Georgia state law prohibits tickets from being bought, sold or handed off within a 2,700 foot boundary around the Augusta National Golf Club.[154][155]

Open applications for practice rounds and individual daily tournament tickets have to be made nearly a year in advance and the successful applicants are chosen by random selection. Series badges for the actual tournament, that is a badge valid for all four tournament rounds, are made available and sold only to individuals of a patrons list, which is closed. A waiting list for the patrons list was opened in 1972 and closed in 1978. It was reopened in 2000 and subsequently closed once again.[156][157] Individuals who are fortunate enough to be on the patron list are given the recurring opportunity to purchase series badges each year for life. According to Augusta National, after the death of a badge holder, the series badge account is transferable only to a surviving spouse and cannot be transferred to other family members.[156][158][159]

In 2008, as part of their Junior Pass Program, the Masters also began allowing children (between the ages of 8 and 16) to enter on tournament days for free if they are accompanied by the patron who is the original applicant of his or her series badge. The Junior Pass Program does not apply to individual daily tournament tickets, only to series badge patrons.[160][155]

The difficulty in acquiring Masters badges has made the tournament one of the largest events on the secondary resale ticket market.[161] Since a majority of the badges for the Masters are made available to the same group of patrons each year, these perennial ticket holders sometimes decide to sell their badges through large ticket marketplaces and/or third party ticket brokers. Although they do so at their own detriment as this action is strictly prohibited in the ticket purchase agreement and ticket policy.[162]

Notes

- ^ Notable exception includes the 2020 Masters Tournament, which was played in November due to the suspension of the 2019–20 PGA Tour from March to mid-June due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Further reading

- Bantock, Jack (April 5, 2023). "For nearly 50 years, only Black men caddied The Masters. One day, they all but vanished". CNN.

References

- ^ a b c d "2014 Masters Preview". Sports Network. April 9, 2014. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ Bacon, Shane (July 16, 2012). "British Open or Open Championship? The debate stops now". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Ryan, Shane (July 14, 2015). "Americans: It's okay to call this major "The British Open," and don't let anyone tell you otherwise". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Masters Milestones". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Kelley, Brent. "Do Masters Champions Get to Keep the Green Jacket?". About.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ a b Owen, David (1999). The Making of the Masters: Clifford Roberts, Augusta National, and Golf's Most Prestigious Tournament. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85729-9.

- ^ Sampson, Curt (1999). The Masters: Golf, Money, and Power in Augusta, Georgia. New York City: Villard Books. p. 22. ISBN 0375753370.

- ^ a b Boyette, John (April 3, 2006). "Augusta National's natural beauty was born in nursery". Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "History of the Club". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ Although front and back are the terms more commonly used, for the Masters they are called the "first" and "second" nines

- ^ "The Augusta National Golf Club". February 8, 2012. Archived from the original on March 27, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Boyette, John (April 10, 2002). "With 1 shot, Sarazen gave Masters fame". The Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Past Winners & Results". Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "The Macon Telegraph 17 Mar 1940, page 9". Newspapers.com. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ "1963: Jack Nicklaus wins second pro Masters". The Augusta Chronicle. March 22, 2012. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ "1965: Nicklaus wins by nine to shatter Masters record". The Augusta Chronicle. March 22, 2012. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "1966: Jack Nicklaus first to win consecutive Masters". The Augusta Chronicle. March 22, 2012. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "1975: Nicklaus wins fifth Masters as Elder breaks color barrier". The Augusta Chronicle. March 23, 2012. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Records & Stats – Tournaments Entered". Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Historical Records & Stats – Cut Information". Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ "World Golf Hall of Fame Profile: Roberto De Vicenzo". World Golf Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ McDaniel, Pete (2000). "The trailblazer – Twenty-five years ago, Lee Elder became the first black golfer in the Masters". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ a b Diaz, Jaime (September 11, 1990). "Augusta National Admits First Black Member". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- ^ a b "Historical Records & Stats – Champions / Winning Statistics". Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Ballard, Sarah. "My, Oh Mize". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ^ "Tournament Results: 1996". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ Brown, Clifton (March 13, 2003). "City of Augusta Is Sued Over Protest at the Masters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ "Court Rejects Burk Appeal". The New York Times. October 4, 2003. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ "To Burk, No Point Picketing Masters". The New York Times. February 29, 2004. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ Bondy, Filip (April 7, 2010). "Masters chairman Billy Payne rips Tiger Woods for 'disappointing all of us'". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on April 10, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ Svrluga, Barry (April 8, 2010). "Billy Payne disappointed in Tiger Woods's 'egregious' behavior". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Billy Payne's remarks regarding Tiger Woods playing at Augusta". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Matthews, Chris (April 15, 2013). "As it happened: Scott wins US Masters". TVNZ. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Jordan Spieth, 21, leads Masters wire to wire for 1st major win". ESPN. Associated Press. April 13, 2015. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Harig, Bob (March 13, 2020). "Augusta announces Masters will be postponed". ESPN. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Westin, David (April 7, 2001). "Purse exceeds $1 Million". The Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ Reilly, Rick (April 21, 1986). "Day Of Glory For A Golden Oldie". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Nicklaus, Jack; Bowden, Ken (1974). Golf My Way. Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-51350-4.

- ^ "$9,000,000 Masters Results". The Sports Network. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "2014 Masters Prize Money Announced". Augusta Chronicle. April 12, 2014. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ Lukas, Paul. "The real story behind the green jacket". ESPN. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ Lispey, Rick (April 10, 1995). "Master Teacher: Nearly forgotten now, teaching pro Henry Picard was a big star when he won the 1938 Masters". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "Michael Kernicki hosts Major Championship at Canterbury Golf Club". GolfGuide.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ "Masters-style green jacket bought for $5 at Toronto thrift store sells for $139K". Toronto Star. Associated Press. April 10, 2017. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ "Utah's Tony Finau moves into the Masters top 10 and earns some crystal with a 66". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ "The Masters Trophy facts: Size, weight, history and more". GolfNewsNet.com. September 19, 2016. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Awards & Trophies". Masters.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Hennessey, Stephen (April 4, 2014). "Inaugural Drive, Chip and Putt Championship has juniors living Augusta National dreams". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Masters unveils drive, chip and putt contest". USA Today. Associated Press. April 8, 2013. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Harig, Bob (April 1, 2018). "Drive, Chip & Putt winners crowned at Augusta". ESPN. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Herrington, Ryan (April 4, 2018). "Masters 2018: Augusta National Women's Amateur Championship to debut in 2019". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Romine, Brentley (January 28, 2019). "Six players, including Arizona's Yu-Sang Hou, complete Augusta National Women's Amateur field". Golf Channel. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Uhles, Steven (April 9, 2008). "Par-3 Contest will be family show". The Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ "Watch Justin Thomas and Rickie Fowler Make Back-to-Back Aces on the Same Hole". Golf Digest.

- ^ "About The Par 3 Contest". Masters Tournament. Archived from the original on May 19, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ "Seamus Power Completes Back to Back Hole in Ones Masters Par 3 Contest". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ "Par 3 Contest". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ Kelley, Brent. "The Par-3 Contest at The Masters". About.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ "History: The Trophy Case". Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ "Players – Qualifications for Invitation". Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- ^ "The Masters Tournament: The Golf Event of 2024 and the Years to come". ELMENS. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "Arnold Palmer to hit opening Masters tee shot". Golf Today. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ Gola, Hank (April 8, 2011). "Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus kick off 2011 Masters as honorary starters with tee shots at Augusta". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on April 14, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ^ Ferguson, Doug (March 16, 2016). "Palmer to skip opening tee shot at Masters". Albany Times Union. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Masters 2016: Arnold Palmer makes poignant appearance on 1st tee". The Guardian. April 7, 2016. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ "Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus join Masters tribute to Arnold Palmer". The Guardian. April 6, 2017. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ "Fit for a King: Arnold Palmer honored in moving tribute at Augusta National". Golf.com. April 4, 2017. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ "Tom Watson accepts invite to join Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player as honorary starters at the Masters". ESPN. January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions at the Masters". Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- ^ "Masters Club". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on January 9, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- ^ "Masters Champions Dinner: Everything you need to know". March 15, 2017. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Bonk, Thomas (April 7, 1998). "It's Food That's Fit for This Golf King". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Both, Andrew (April 4, 2016). "Feature: Zoeller's ex-caddie recalls how Woods broke the ice". Reuters.

- ^ "Perfecting pimento: gourmet gives us our own recipe". Golf Digest. 2003.

- ^ "Augusta Georgia: Features:Pimiento cheese is soul food of the South 04/14/02". Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ "The Rich, Creamy, Piquant History of the Masters' Pimento Cheese Sandwich". InsideHook. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Benson, Pat (March 18, 2024). "Under Armour Drops Pimento Cheese-Inspired Masters Collection". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Wright (April 11, 2013). "A sandwich stumper at the Masters". ESPN.com. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Overdeep, Meghan (March 5, 2024). "Augusta National's "Taste of the Masters" Hosting Kits Are Back". Southern Living. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Hennessey, Stephen (April 10, 2022). "Masters 2022: I ate and graded every item on the Augusta National concession menu (again)". Golf Digest. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "Tour caddies at Augusta?". Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. November 12, 1982. p. 14. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Wade, Harless (April 6, 1983). "Tradition bagged at Masters". Spokane Chronicle. Washington. p. C1. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (April 10, 1983). "New Masters caddies collide". Sunday Star-News. Wilmington, North Carolina. p. 6D. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Reilly, Rick (April 21, 1997). "Strokes of Genius". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Loomis, Tom (April 6, 1973). "Chi Chi prefers own caddy". Toledo Blade. Ohio. Associated Press. p. 30. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Westchester winner may bypass events". Victoria Advocate. Texas. Associated Press. August 26, 1974. p. 1B. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Touring golf pros prefer their own caddies". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. May 5, 1974. p. 76. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Open golfers to pick own caddies in 1976". Toledo Blade. Ohio. Associated Press. November 15, 1975. p. 17. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Break for some". Rome News-Tribune. Georgia. Associated Press. January 18, 1976. p. 3B. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Hoggard, Rex (November 9, 2020). "Masters changes 36-hole cut rules, 10-shot rule removed". Golf Channel. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Harig, Bob (April 10, 2013). "Masters tweaks qualifications". ESPN. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Masters goes to sudden death". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Florida. Associated Press. February 6, 1976. p. 2E. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ^ "In sudden death, Masters playoff shifts to no. 10". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. April 11, 1979. p. D2. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ^ "Course Tour: 2012 Masters". PGA of America: Major Championships. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ "Changes afoot at Augusta". BBC Sport. August 7, 2001. Archived from the original on December 27, 2002. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ Spousta, Tom (June 29, 2005). "Augusta National plans to add length". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ "Row over Augusta changes goes on". BBC Sport. April 5, 2006. Archived from the original on April 12, 2006. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ Harig, Bob (January 31, 2019). "Augusta National lengthens fifth hole ahead of 2019 Masters". ESPN. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Westin, David (March 28, 2001). "Desire for faster greens led to use of Bentgrass". CNNSI.com & The Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ "Golf Course Guide". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ "2008 Tournament Invitees". masters.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Martin (April 9, 2002). "The Masters: Augusta bows to change with a pompous flourish". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ "2010 Masters Tournament Invitees". Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ^ "2009 Tournament Invitees". Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ Harig, Bob (January 22, 2014). "Masters, Latin America team up". ESPN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Woodard, Adam (April 5, 2023). "Augusta National chairman Fred Ridley announces Masters, ANWA invitations for future NCAA champions". Golfweek. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ Lavner, Ryan (April 5, 2023). "Augusta National announces changes to qualifying criteria for 2024 Masters". Golf Channel. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Myers, Alex (April 5, 2023). "Augusta National announces NCAA D-I champ now gets a Masters invite". Golf Digest. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ "Masters: Host Courses and Winners". Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- ^ "Masters playoff format is changed". CNN. April 7, 2004. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ "Top Finishers". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "Scoring Statistics". www.masters.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Harig, Bob (November 4, 2012). "Guan Tianlang, 14, headed to Masters". ESPN. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ "Tianlang Guan youngest to make cut". ESPN. April 12, 2013. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ "Tiger Woods sets all-time record for consecutive made cuts at Masters 2024".

- ^ Rogers, Paul (April 8, 2023). "Couples Makes Historic Cut as Some Major Names Miss". Augusta National Golf Club. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ Roberson, Doug (April 8, 2012). "Oosthuizen gives away souvenir after rare double-eagle". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Masters Tournament". PGA Tour. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c Sandomir, Richard (April 7, 1998). "CBS and the Masters Keep Business Simple". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Freeman, Denne H. (April 10, 1997). "Augusta's front nine cloaked in secrecy". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Chase, Chris (April 10, 2014). "Why isn't the Masters on TV all day?". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Sandomir, Richard (October 11, 2007). "ESPN Replaces USA as Early-Round Home of the Masters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ "ESPN will show first two rounds of 2008 Masters tournament". ESPN. October 10, 2007. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- ^ "2018 Masters broadcast will use shot tracer technology". Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 7, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ "Get ready for Amen Corner live". March 30, 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ "DirecTV's first live 4K show is the Masters golf tournament". Engadget. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ "The Masters in 4K: DirecTV, CBS Sports Tee Up First Live 4K UHD Broadcast in U.S." Sports Video Group. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ "DirecTV doubles its live 4K broadcasts for this year's Masters". Engadget. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Dachman, Jason Dachman. "AT&T/DirecTV Will Deliver The Masters in 4K HDR for the First Time". Sports Video Group. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (June 14, 2019). "Inside the Cultish Dreamworld of Augusta National". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 15, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Hinds, Richard (April 5, 2007). "Why coverage of US Masters is so polite". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Martzke, Rudy (April 13, 2003). "CBS managed to get Masters right despite silence on protests". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Tim. "Is the Masters really the most prestigious sporting event in America?". WorldGolf. Golf Channel. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ "How The Masters Theme Song Came To Be". Deadspin. April 7, 2012. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "Mercedes, UPS Form New Partnerships with Masters Tournament" (Press release). Augusta National Golf Club. April 29, 2013. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Stewart, Larry (August 28, 2004). "Masters Is Back to Commercials". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Yen, Yi-Wyn (April 8, 2003). "The Battle of Augusta Hootie vs. Martha: A Chronology of Developments in Golf's Most Famous Feud, Between Martha Burk, the Chairwoman of the National Council Of Women's Organizations (NCWO), and Hootie Johnson, the Chairman of Augusta National Golf Club". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "The Masters". Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "BBC Sport keeps Masters contract". BBC Sport. October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Dams, Tim. "Sky Sports shuts BBC out of live golf with Masters deal". Broadcast. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Streeter, Joe (November 20, 2019). "Sky Sports lands exclusive live UK Masters rights from 2020". Insider Sport. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ Corrigan, James (September 22, 2010). "Sky seizes share of the Masters from BBC". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "We are fully committed to providing a public service – without public funding". Irish Independent. August 12, 2007. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ "The Masters: Sky Sports announces multi-year extension of broadcast agreement with Augusta National". Sky Sports. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ Houston, William (April 10, 2008). "As usual, Woods is the star of Masters coverage". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ Maloney, Val (April 10, 2013). "TSN and Global partner to sell The Masters". Media in Canada. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ The Sports Network and Global Television Network (April 5, 2013). "TSN and Global Partner to Give Canadians Complete Coverage of The Masters". Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ "Television wars continue as CTV takes Masters deal away from Global". Yahoo! Sports Canada. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.