Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

| King Charles Spaniel | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

'King Charles' Colour | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | English Toy Spaniel Toy Spaniel Charlies Prince Charles Spaniel Ruby Spaniel Blenheim Spaniel | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | Great Britain | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||

The King Charles Spaniel (also known as the English Toy Spaniel) is a small dog breed of the spaniel type. In 1903, The Kennel Club combined four separate toy spaniel breeds under this single title. The other varieties merged into this breed were the Blenheim, Ruby and Prince Charles Spaniels, each of which contributed one of the four coat colours now seen in the breed.

Thought to have originated in East Asia, and possibly acquired by European traders via the Spice Road, early toy spaniels were first seen in Europe during the 16th century. They became linked with English royalty during the rule of Queen Mary I (from 1553-1558), eventually earning their name after being made famous by their association with King Charles II. Ruling from 1660-1685, Charles II owned many small dogs which accompanied him and his entourage about their daily business. Members of the breed were also owned by Queen Victoria (Dash) and her great-granddaughter Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia.

The modern King Charles Spaniel, and the other types of toy spaniels, are likely the result of crossbreeding historic spaniels with other East Asian breeds (such as the Japanese Chin, Pekingese, and the Pug) in the early 19th century. This was done mainly to reduce the size of the nose and snout, as was the style of the day. The 20th century saw attempts to restore lines of King Charles Spaniels to the breed of Charles II's time. These included the unsuccessful Toy Trawler Spaniel and the now popular Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. The Cavalier is slightly larger, with a flat head and a longer nose, while the King Charles is smaller, with a domed head and a flat face.

Historically the breeds that were merged into the King Charles Spaniel were used for hunting; due to their stature they were not well suited. They have kept their hunting instincts, but do not exhibit high energy and are better suited to being lapdogs. The modern breed is prone to several health problems, including cardiac conditions and a range of eye problems.

History

The fact that dogs are always part of a royal Japanese present suggested to the Commodore the thought that possibly one species of spaniel now in England may be traced to a Japanese origin. In 1613, when Captain Saris returned from Japan to England, he carried to the King a letter from the Emperor, and presents in return for those sent to him by his Majesty of England. Dogs probably formed part of the gifts and thus may have been introduced into the Kingdom the Japanese breed. At any rate, there is a species of Spaniel in England which it is hard to distinguish from the Japanese dog. The species sent by the Emperor is by no means common even in Japan. It is never seen running about the streets, or following its master in his walks, and the Commodore understood that they were costly.

The King Charles Spaniel may share a common ancestry with the Pekingese and Japanese Chin.[2]

The red and white variety of toy spaniel was first seen in paintings by Titian,[3] including the Venus of Urbino (1538), where a small dog is used as a symbol of female seductiveness.[4] Further paintings featuring these toy spaniels were created by Palma Vecchio and Paolo Veronese during the 16th century. These dogs already had high domed heads with short noses, although the muzzles were more pointed than they are today. These Italian toy spaniels may have been crossed with local small dogs such as the Maltese and also with imported Chinese dogs.[3] The Papillon is the continental descendant of similar toy-sized spaniels.[5]

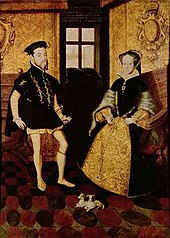

The earliest recorded appearance of a toy spaniel in England was in a painting of Queen Mary I and King Philip.[6] Mary, Queen of Scots, was also fond of small toy dogs, including spaniels,[7] showing the fondness of the British royalty for these types of dogs before Charles II.[6]

King Henry III of France owned a number of small spaniels, which were called Damarets. Although one of the translations of John Caius' 1570 Latin work De Canibus Britannicis talks of "a new type of Spaniel brought out of France, rare, strange, and hard to get",[8] this was an addition in a later translation, and was not in the original text.[8] Caius did discuss the "Spainel-gentle, or Comforter" though, which he classified as a delicate thoroughbred. This spaniel was thought to originate from Malta and was sought out only as a lapdog for "daintie dames".[9]

Captain John Saris may have brought back examples of toy spaniels from his voyage to Japan in 1613,[2] a theory proposed by Commodore Matthew C. Perry during his expeditions to Japan on behalf of the United States in the mid-19th century. He noted that dogs were a common gift and thought that the earlier voyage of Captain Saris introduced a Japanese type of spaniel into England.[1]

17th century and Charles II

In the 17th century, toy spaniels began to feature in paintings by Dutch artists such as Caspar Netscher and Peter Paul Rubens. Spanish artists, including Juan de Valdés Leal and Diego Velázquez, also depicted them; in the Spanish works, the dogs were tricolour, black and white or entirely white. French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon would later describe these types of dogs as crosses between spaniels and Pugs.[5]

King Charles II of England was very fond of the toy spaniel, which is why the dogs now carry his name,[10] although there is no evidence that the modern breeds are descended from his particular dogs. He is credited with causing an increase in popularity of the breed during this period. Samuel Pepys' diary describes how the spaniels were allowed to roam anywhere in Whitehall Palace, including during state occasions.[10] In an entry dated 4 September 1667, describing a council meeting, Pepys wrote, "All I observed there was the silliness of the King, playing with his dog all the while and not minding the business."[11][12] Charles' sister Princess Henrietta was painted by Pierre Mignard holding a small red and white toy-sized spaniel.[13] Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth, writing in her 1911 work Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors, theorised that after Henrietta's death at the age of 26 in 1670, Charles took her dogs for himself.[13]

After Charles II

Toy spaniels continued to be popular in the British court during the reign of King James II, through that of Queen Anne. Popular types included those of the white and red variety.[14] Following the Glorious Revolution in 1688 and the reign of King William III and Queen Mary II, the Pug was introduced into Britain which would eventually lead to drastic physical changes to the King Charles Spaniel.[15] Comparisons between needlework pictures of English toy spaniels and the continental variety show that changes had already begun to take place in the English types by 1736, with a shorter nose being featured and the breed overall moving away from the one seen in earlier works by Anthony van Dyck during the 17th century.[16]

English toy spaniels remained popular enough during the 18th century to be featured frequently in literature and in art. On Rover, a Lady's Spaniel, Jonathan Swift's satire of Ambrose Philips's poem to the daughter of the Lord Lieutenant, describes the features of an English toy, specifying a "forehead large and high" among other physical characteristics of the breeds.[17] Toy spaniels and Pugs were featured in both group portraits and satirical works by William Hogarth.[18] Toy spaniels were still popular with the upper classes as ladies' dogs, despite the introduction of the Pug;[19] both Thomas Gainsborough's portrait of Queen Charlotte from 1781 and George Romney's 1782 Lady Hamilton as Nature feature toy spaniels with their mistresses. The toy spaniels of this century weighed as little as 5 pounds (2.3 kg),[20] although they were thought to be the dog breed most prone to becoming overweight, or "fattened".[21]

19th century and the Blenheim Spaniel

The varieties of toy spaniel were occasionally used in hunting, as the Sportsman's Repository reported in 1830 of the Blenheim Spaniel: "Twenty years ago, His Grace the Duke of Marlborough was reputed to possess the smallest and best breed of cockers in Britain; they were invariably red–and–white, with very long ears, short noses, and black eyes."[22] During this period, the term "cocker" was not used to describe a Cocker Spaniel, but rather a type of small spaniel used to hunt woodcock. The Duke's residence, Blenheim Palace, gave its name to the Blenheim Spaniel. The Sportsman's Repository explains that toy spaniels are able to hunt, albeit not for a full day or in difficult terrain: "The very delicate and small, or 'carpet spaniels,' have exquisite nose, and will hunt truly and pleasantly, but are neither fit for a long day or thorny covert."[23] This idea was supported by Vero Shaw in his 1881 work The Illustrated Book of the Dog,[23] and by Thomas Brown in 1829 who wrote, "He is seldom used for field–sports, from his diminutive size, being easily tired, and is too short in the legs to get through swampy ground."[24] During the 19th century, the Maltese was still considered to be a type of spaniel, and thought to be the parent breed of toy spaniels, including both the King Charles and Blenheim varieties.[22]

The breeds of toy spaniel often rivalled the Pug in popularity as lapdogs for ladies. The disadvantage of the breeds of toy spaniel was that their long coats required constant grooming.[22] By 1830, the toy spaniel had changed somewhat from the dogs of Charles II's day. William Youatt in his 1845 study, The Dog, was not enamoured of the changes: "The King Charles's breed of the present day is materially altered for the worse. The muzzle is almost as short, and the forehead as ugly and prominent as the veriest bull-dog. The eye is increased to double its former size, and has an expression of stupidity with which the character of the dog too accurately corresponds." Youatt did concede that the breed's long ears, coat and colouring were attractive.[25] Due to the fashion of the period, the toy spaniels were crossed with Pugs to reduce the size of their noses and then selectively bred to reduce it further. By doing this, the dog's sense of smell was impaired, and according to 19th century writers, this caused the varieties of toy spaniel to be removed from participation in field sports.[23] Blunt-Lytton proposed that the red and white Blenheim Spaniels always had the shorter nose now seen in the modern King Charles.[3]

From the 16th century, it was the fashion for ladies to carry small toy-sized spaniels as they travelled around town.[9] These dogs were called "Comforters" and given the species biological classification of Canis consolator by 19th-century dog writers. By the 1830s, this practice was no longer in vogue, and these types of spaniels were becoming rarer.[26] "Comforter" was given as a generic term to lapdogs, including the Maltese, the English Toy and Continental Toy Spaniels, the latter of which was similar to the modern Phalène.[27] It was once believed that the dogs possessed some power of healing: in 1607 Edward Topsell repeated Caius' observation that "these little dogs are good to asswage the sickness of stomach, being oftentimes thereunto applied as a plaister preservative, or bourne in the bosum of the diseased and weak person, which effect is performed by their moderate heat."[28] By the 1840s, "Comforter" had dropped out of use, and the breed had returned to being called Toy Spaniels.[29] The first written occurrence of a ruby coloured toy spaniel was a dog named Dandy, owned by a Mr Garwood in 1875.[30]

The dogs continued to be popular with royalty. In 1896, Otto von Bismarck purchased a King Charles Spaniel from an American kennel for $1,000.[31] The dog weighed less than 2 pounds (0.9 kg), and had been disqualified from the Westminster Kennel Club the previous year on account of its weight.[31] The average price was lower than that paid by Bismarck. In 1899, the price ranged between $50 and $200 for a King Charles or Blenheim,[32] with the Ruby and Prince Charles Spaniel ranging between $50 and $150.[33][34]

Anne Brontë's "Flossy", given to her by the Robinson children when she left her governorship of them, was a King Charles Spaniel.

Conformation showing and the 20th century

In 1903, the Kennel Club attempted to amalgamate the King James (black and tan), Prince Charles (tricolour), Blenheim and Ruby spaniels into a single breed called the Toy Spaniel. The Toy Spaniel Club, which oversaw those separate breeds, strongly objected, and the argument was only resolved following the intervention of King Edward VII, who made it clear that he preferred the name "King Charles Spaniel".[35] In 1904, the American Kennel Club followed suit, combining the four breeds into a single breed known as the English Toy Spaniel.[36] The Japanese Spaniel was also considered a type of toy spaniel,[37] but was not merged into the new breed and was recognised as a breed in its own right.[35]

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia owned a King Charles Spaniel at the time of the shooting of the Romanov family on 17 July 1918. Eight days later, Nicholas Sokolov of the White Forces found a clearing where he believed the bodies of the Romanov family had been burnt, and discovered the corpse of a King Charles Spaniel at the site.[38] In 1920s, the Duchess of Marlborough bred so many King Charles Spaniels at Blenheim Palace that her husband moved out and later evicted the Duchess herself.[39]

Blunt-Lytton documented her attempts in the early 20th century to re-breed the 18th-century type of King Charles Spaniel as seen in the portraits of King Charles II.[40] She used the Toy Trawler Spaniel, a curly haired, mostly black, small to medium-sized spaniel, and cross-bred these dogs with a variety of other breeds, including Blenheim Spaniels and Cocker Spaniels, in unsuccessful attempts to reproduce the earlier style.[30]

The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel originated from a competition held by American Roswell Eldridge in 1926. He offered a prize fund for the best male and female dogs of "Blenheim Spaniels of the old type, as shown in pictures of Charles II of England's time, long face, no stop, flat skull, not inclined to be domed, with spot in centre of skull."[41] Breeders entered what they considered to be sub-par King Charles Spaniels. Although Eldridge did not live to see the new breed created, several breeders banded together and created the first breed club for the new Cavalier King Charles Spaniel in 1928, with the Kennel Club initially listing the new breed as "King Charles Spaniels, Cavalier type". In 1945, the Kennel Club recognised the new breed in its own right.[41] The American Kennel Club did not recognise the Cavalier until 1997.[42]

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, continued the connection between royalty and the King Charles Spaniel, attending Princess Anne's tenth birthday party with her dog Rolly in 1960.[43][44] Elizabeth II has also owned King Charles Spaniels in addition to the dogs most frequently associated with her, the Pembroke Welsh Corgi.[45]

In 2008, the BBC documentary Pedigree Dogs Exposed was critical of the breeding of a variety of pedigree breeds including the King Charles Spaniel. The show highlighted issues involving syringomyelia in both the King Charles and Cavalier breeds. Mark Evans, the chief veterinary advisor for the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), said, "Dog shows using current breed standards as the main judging criteria actively encourage both the intentional breeding of deformed and disabled dogs and the inbreeding of closely related animals";[46] this opinion was seconded by the Scottish SPCA.[46] Following the programme, the RSPCA ended its sponsorship of the annual Crufts dog show,[47] and the BBC declined to broadcast the event.[48]

The King Charles Spaniel is less popular than the Cavalier in both the UK and the US. In 2010, the Cavalier was the 23rd most popular breed, according to registration figures collected by the American Kennel Club, while the English Toy Spaniel was the 126th.[49] In the UK, according to the Kennel Club, the Cavalier is the most popular breed in the Toy Group, with 8,154 puppies registered in 2010, compared to 199 registrations for King Charles Spaniels.[50] Due to the low number of registrations, the King Charles was identified as a Vulnerable Native Breed by the Kennel Club in 2003 in an effort to help promote the breed.[51]

Description

The King Charles has large dark eyes, a short nose, a high domed head and a line of black skin around the mouth.[7] On average, it stands 9 to 11 inches (23 to 28 cm) at the withers, with a small but compact body.[52] The breed has a traditionally docked tail, except in the UK and some other European Countries where docking and cropping has been illegal since 2006.[53][non-primary source needed] Cropping of ears has been illegal in the UK for over 100 years.[54] It has the long pendulous ears typical of a spaniel and its coat comes in four varieties, trait it shares with its offshoot, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.[52][55]

The four sets of markings reflect the four former breeds from which the modern breed was derived. Black and tan markings are known as "King Charles", while "Prince Charles" is tricoloured, "Blenheim" is red and white, and "Ruby" is a single-coloured solid rich red.[52] The "King Charles" black and tan markings typically consist of a black coat with mahogany/tan markings on the face, legs and chest and under the tail. The tricoloured "Prince Charles" is mostly white with black patches and mahogany/tan markings in similar locations to the "King Charles". The "Blenheim" has a white coat with red patches, and should have a distinctive red spot in the center of the skull.[56][57]

King Charles Spaniels are often mistaken for Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. There are several significant differences between the two breeds, the principal being the size.[41] While the Cavalier weighs on average between 13 and 18 pounds (5.9 and 8.2 kg),[55] the King Charles is smaller at 8 to 14 pounds (3.6 to 6.4 kg).[52] In addition, their facial features, while similar, are distinguishable: the Cavalier's ears are set higher and its skull is flat, while the King Charles' is domed. Finally, the muzzle length of the King Charles tends to be shorter than the typical muzzle on a Cavalier.[41]

The American Kennel Club has two classes, English Toy Spaniel (B/PC) (Blenheim and Prince Charles) and English Toy Spaniel (R/KC),[36] while in the UK, the Kennel Club places the breed in a single class.[58] Under the Fédération Cynologique Internationale groups, the King Charles is placed in the English Toy Spaniel section within the Companion and Toy Dog Group, along with the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.[59]

Temperament

The King Charles is a friendly breed, to the extent that it is not typically as suitable as a watchdog as some breeds,[52] though it may still bark to warn its owners of an approaching visitor.[7] It is not a high energy breed, and enjoys the company of family members,[52] being primarily a lapdog.[7] Although able to bond well with children and tolerant of them, it will not accept rough handling. It prefers not to be left alone for long periods. Known as one of the quietest toy breeds, it is suitable for apartment living.[52]

The breed can tolerate other pets well,[52] although the King Charles still has the hunting instincts of its ancestors and may not always be friendly towards smaller animals.[36] It is intelligent enough to be used for obedience work and, due to its stable temperament, it can be a successful therapy dog for hospitals and nursing homes.[7]

Health

A natural bobtail can be found in some members of the breed, which is not a mutation of the T-box gene, and so is allowed under conformation show rules.[60] Health-related research on the breed has been limited, with no major studies conducted in Britain. However, it has been included in studies outside the UK, including by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) in the United States.[61] The King Charles Spaniel has a number of eye and respiratory system disorders common to brachycephalic dogs, and endocrine and metabolic diseases common to small breeds,[62] as well as specific breed-associated health conditions.[61] The average lifespan is 10 to 12 years,[63][64] and the breed should be able to reproduce naturally.[61]

Eye and heart conditions

The eye problems associated with the King Charles Spaniel include cataracts, corneal dystrophy, distichia, entropion, microphthalmia, optic disc drusen, and keratitis. Compared to other breeds, the King Charles Spaniel has an increased risk of distichia (where extra eyelashes or hairs cause irritation to the eye). Inheritance is suspected in the other conditions, with ages of onset ranging from six months for cataracts to two to five years for corneal dystrophy.[65]

Heart conditions related to the King Charles Spaniel include mitral valve disease, in which the mitral valve degrades, causing blood to flow backwards through the chambers of the heart and eventually leading to congestive heart failure.[66][67] Patent ductus arteriosus, where blood is channelled back from the heart into the lungs, is also seen and can lead to heart failure.[68] Both of these conditions present with similar symptoms and are inheritable.[67][68] The OFA conducted a survey on cardiac disease, where of 105 breeds, the King Charles Spaniel was found to be 7th worst, with 2.1% of 189 dogs affected.[69]

Other common issues

Being a brachycephalic breed, King Charles Spaniels can be sensitive to anesthesia.[70] This is because in brachycephalic dogs, there is additional tissue in the throat directly behind the mouth and nasal cavity, known as the pharynx, and anesthesia acts as a muscle relaxant causing this tissue to obstruct the dogs' narrow airways.[71] These narrow airways can decrease the dogs' ability to exercise properly and increase their susceptibility to heat stroke.[71] Other congenital and hereditary disorders found in the King Charles Spaniel are hanging tongue, where a neurological defect prevents the tongue from retracting into the mouth; diabetes mellitus, which may be associated with cataracts; cleft palate and umbilical hernia.[72] The English Toy Spaniel Club of America recommends that umbilical hernias be corrected only if other surgery is required, due to the risk of surgery in brachycephalic breeds.[73] In another study conducted by the OFA, the King Charles Spaniel was the 38th worst of 99 breeds for patella luxation; of 75 animals tested, 4% were found to have the ailment.[74] However, surveys conducted by the Finnish breed club between 1988 and 2007 found that the occurrences were higher in some years, ranging from 5.3% to 50%.[61]

There are several breed traits which may cause concern as health issues.[75] They include skull issues such as an open fontanelle, where in young dogs there is a soft spot in the skull; it is common in dogs under a year old. A complication from that condition is hydrocephalus, also known as water on the brain. This condition may cause neurological symptoms that require the dog to be euthanised. Fused toes, where two or more of the dog's toes are fused together, may seem to be a health issue but this breed trait is not a cause for concern.[73]

Urban myth

An urban legend claims that Charles II issued a special decree granting King Charles Spaniels permission to enter any establishment in the UK,[76][77] overriding "no dog except guide dogs" rules. A variant of this myth relates specifically to the Houses of Parliament.[78][79] This myth is sometimes instead applied to the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.[80]

The UK Parliament website states: "Contrary to popular rumour, there is no Act of Parliament referring to King Charles spaniels being allowed anywhere in the Palace of Westminster. We are often asked this question and have thoroughly researched it."[78] [failed verification] Similarly, there is no proof of any such law covering the wider UK. A spokesman for the Kennel Club said: "This law has been quoted from time to time. It is alleged in books that King Charles made this decree but our research hasn't tracked it down."[76]

See also

References

- Specific

- ^ a b Hawks, Francis L.; Perry, Commodore Matthew C. (1856). Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan. Washington, D.C.: Beverley Tucker. p. 369.

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 94

- ^ a b c Lytton (1911): p. 14

- ^ Cohen, Simona (2008). Animals as Disguised Symbols in Renaissance Art. Boston, MA: Brill. p. 137. ISBN 978-90-04-17101-5.

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 15

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 38

- ^ a b c d e Rice, Dan (2002). Small Dog Breeds. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-7641-2095-4.

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 16

- ^ a b Caius, John; Fleming, Abraham (1576) [1570]. De Canibus Britannicis (in Latin). London, UK: Richard Johnes. p. 6.

- ^ a b Shaw (1881): p. 162

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 52

- ^ Pepys, Samuel (1893). "4 September 1667". In Wheatley, Henry B. (ed.). . George Bell & Sons – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 17

- ^ Walsh (1876): p. 667

- ^ Moffat (2006): p. 19

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 19

- ^ Browning, William Ernst, ed. (1910). The Poems of Jonathan Swift. Vol. 1. London, UK: G. Bell and Sons. p. 288.

- ^ Hogarth, William (1833). Anecdotes. London UK: J.R. Nichols and Son. p. 374.

- ^ Bowon, Edgar Peter (2006). Best in Show : the Dog in Art from the Renaissance to Today. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-89090-143-4.

- ^ Wood, John George (1862). Natural History Picture Book: Mammalia. London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge, Warne, and Routledge. p. 102.

- ^ Anderson, James (1800). Recreations in Agriculture, Natural–History, Arts, and Miscellaneous literature. Vol. 2. London, UK: T. Bensley. p. 241.

- ^ a b c Shaw (1881): p. 163

- ^ a b c Shaw (1881): p. 164

- ^ Brown (1829): p. 295

- ^ Youatt (1852): p. 78

- ^ Brown (1829): p. 301

- ^ Hungerland, Jacklyn E. (2003). Papillions. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7641-2419-8.

- ^ Brown (1829): p. 302

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 36

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 40

- ^ a b "Gillie Sells for $1,000" (PDF). The New York Times. 17 April 1896. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Diehl (1899): p. 39

- ^ Diehl (1899): p. 41

- ^ Diehl (1899): p. 42

- ^ a b Jackson, Frank (1990). Crufts: The Official History. London, UK: Pelham Books. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7207-1889-8.

- ^ a b c "English Toy Spaniel Did You Know?". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Diehl (1899): p. 38

- ^ Dalley, Jan (7 January 1996). "Grave Affairs". The Independent. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "Gladys, Duchess of Marlborough: the aristocrat with attitude". The Telegraph. 7 February 2011.

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 80

- ^ a b c d Coile (2008): p. 9

- ^ Moffat (2006): p. 23

- ^ "Princess Anne's 10th Birthday". The Herald. Newsquest. 16 August 1960. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Gilmore, Eddy (29 August 1959). "Anne Happy, Phillip Miffed as Ike Leaves Family". Gadsden Times. Roger Quinn. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "Queen, Looking Well, Goes To Palace". The Evening Times. Newsquest. 18 January 1960. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ a b Donnelly, Brian (16 September 2008). "Crufts Hit by 'Deformed' Breeds Row". The Herald. Newsquest. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Sugden, Joanne (15 September 2008). "RSPCA Pulls Out of Crufts Over Breeding Row". The Times. News Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Kiss, Jemima (12 December 2008). "BBC Suspends Coverage of Crufts Dog Show After Four Decades". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "AKC Dog Registration Statistics". American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Comparative Tables of Registrations For the Years 2001 – 2010 Inclusive" (PDF). The Kennel Club. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Hankins, Justine (19 February 2006). "The Dying Breeds". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Palika (2007): pp. 232–233

- ^ "Animal Welfare Act: Section 6", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2006 c. 45 (s. 6)

- ^ "Traditionally Docked Breeds". The Kennel Club. 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b Palika (2007): p. 190

- ^ "English Toy Spaniel" (PDF). Canadian Kennel Club. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "King Charles Spaniel Breed Standard". The Kennel Club. December 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Breed and Class Results: King Charles Spaniel". DFS Crufts. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Breeds Nomenclature". Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Routuesittely" (in Finnish). King Charlesin Spaniel r.y. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Kingcharlesinspanieli Jalostuksen tavoiteohjelma" (PDF). King Charlesin Spaniel r.y. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Fleming, J.M.; Creevy K.E., Promislow, D.E.L. (2011). "Mortality in North American Dogs from 1984 to 2004: An Investigation into Age-, Size-, and Breed-Related Causes of Death". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 25 (2): 187–198. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0695.x. ISSN 1939-1676. PMID 21352376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Michell, A. R. (1999). "Longevity of British breeds of dog and its relationships with-sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease". Veterinary Record. 145 (22): 625–9. doi:10.1136/vr.145.22.625. PMID 10619607. S2CID 34557345. "n=22, median=10.1"

- ^ O’Neill, D. G.; Church, D. B.; McGreevy, P. D.; Thomson, P. C.; Brodbelt, D. C. (2013). "Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England" (PDF). The Veterinary Journal. 198 (3): 638–43. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020. PMID 24206631. "n=26, median=12.0, IQR=10.0-14.2"

- ^ Gough, Alex (2010). Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs and Cats. Chichester, UK: Wiley–Blackwell. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4051-8078-8.

- ^ "Breed Health Concerns/Research Interests". American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Mitral Valve Disease". American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Patent Ductus Arteriosus". American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Cardiac Statistics". Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Arden, Darleen (2006). Small Dogs, Big Hearts. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-471-77963-6.

- ^ a b McKay, Scott Alan. "Brachycephalic Syndrome in Dogs and Cats". Peteducation.com. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Disorders by Breed: King Charles Spaniel". Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Breed Profile". English Toy Spaniel Club of America. Archived from the original on 30 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Patella Luxation Statistics". Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Dog Breed Information". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Shops centre ban for 'royal' dog". Manchester Evening News (Jan 2007). 17 February 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "King Charles and a point of law". Dogcast Radio.

- ^ a b "I want the act saying that King Charles spaniels have special rights in the Houses of Parliament". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "Feeding your small breed puppy". Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "Buchlyvie 513 OES". Buchlyvie chapter No 513 Order of The Eastern Star. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- General

- Brown, Thomas (1829). Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs. Edinburgh, UK: Oliver and Boyd.

- Coile, D. Caroline (2008). Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (2nd ed.). Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0-7641-3771-6.

- Diehl, John E. (1899). Toy Dogs. Philadelphia: The Associated Fanciers.

- Lytton, Mrs. Neville (1911). Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors. New York, NY: D Appleton and Company.

- Moffat, Norma (2006). Cavalier King Charles Spaniel: Your Happy Healthy Pet (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-74823-6.

- Palika, Liz (2007). The Howell Book of Dogs: The Definitive Reference to 300 Breeds and Varieties. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-00921-5.

- Shaw, Vero Kemball (1881). The Illustrated Book of the Dog. London, UK; New York, NY: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.

- Walsh, John Henry (1876). British Rural Sports. London: Saville, Edwards and Co.

- Youatt, William (1852) [1845]. The Dog. Philadelphia, PA: Blanchard and Lea.

External links