Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

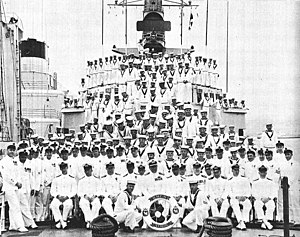

Crew portrait in July 1964

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Yukon |

| Namesake | Yukon River |

| Ordered | 1957 |

| Builder | Burrard Dry Dock, North Vancouver |

| Laid down | 25 October 1959 |

| Launched | 27 July 1961 |

| Commissioned | 25 May 1963 |

| Decommissioned | 3 December 1993 |

| Refit | 1984–85 (DELEX) |

| Identification | DDE 263 |

| Motto | "Only the fit survive"[1] |

| Fate | Sold to the San Diego Oceans Foundation. Sank at Sunken Harbor off San Diego in July 2000. |

| Notes | Gules, a bend wavy or charged with a like bendlet azure, and over all a Malamute sled dog, proper[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Mackenzie-class destroyer |

| Displacement | 2,880 t (2,830 long tons) full load |

| Length | 366 ft (111.6 m) |

| Beam | 42 ft (12.8 m) |

| Draught | 13 ft 6 in (4.1 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 28 kn (51.9 km/h; 32.2 mph) |

| Complement | 228 regular, 170–210 training |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Electronic warfare & decoys |

|

| Armament |

|

HMCS Yukon was a Mackenzie-class destroyer that served in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and later the Canadian Forces. She was the first Canadian naval unit to carry the name. She was named for the Yukon River that runs from British Columbia through Yukon and into Alaska in the United States.

Entering service in 1963, she was primarily used as a training ship on the west coast. She was decommissioned in 1993 and sold for use as an artificial reef and sunk as such at Sunken Harbor off San Diego, California in 2000.

Design

The Mackenzie class was an offshoot of the St. Laurent-class design. Initially planned to be an improved version of the design, budget difficulties led to the Canadian government ordering a repeat of the previous Restigouche class,[2] with improved habitability and better pre-wetting, bridge and weatherdeck fittings to better deal with extreme cold.[3] The original intention was to give the Mackenzie class variable depth sonar during construction, but would have led to delays of up to a year in construction time, which the navy could not accept.[4]

General characteristics

The Mackenzie-class vessels measured 366 feet (112 m) in length, with a beam of 42 feet (13 m) and a draught of 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m).[5][6] The Mackenzies displaced 2,880 tonnes (2,830 long tons) fully loaded and had a complement of 290.[5][note 1]

The class was powered by two Babcock & Wilcox boilers connected to the two-shaft English-Electric geared steam turbines creating 30,000 shaft horsepower (22,000 kW).[5] This gave the ships a maximum speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph).[6]

Armament

The most noticeable change for the Mackenzies was the replacement of the forward 3-inch (76 mm)/50 calibre Mk 22 guns of the St. Laurent design[note 2] with a dual Vickers 3-inch/70 calibre Mk 6 gun mount and the presence of a fire-control director atop the bridge superstructure. The bridge was raised one full deck higher than on previous classes in order to see over the new gun mount. The class did retain the rear dual 3-inch/50 calibre gun mount and for anti-submarine warfare, the class was provided with two Mk 10 Limbo mortars.[3] The ships were initially fitted with Mark 43 torpedoes to supplement their anti-submarine capability, but were quickly upgraded to the Mark 44 launched from a modified depth charge thrower. This was to give the destroyers the ability to combat submarines from a distance.[7]

Sensors

The Mackenzie class were equipped with one SPS-12 air search radar, one SPS-10B surface search radar and one Sperry Mk.2 navigation radar.[3] For detection below the surface, the ships had one SQS-501 high frequency bottom profiler sonar, one SQS-503 hull mounted active search sonar,[3] one SQS-502 high frequency mortar control sonar and one SQS-11 hull mounted active search sonar.

DELEX refit

The DEstroyer Life EXtension (DELEX) refit was born out of the need to extend the life of the steam-powered destroyer escorts of the Canadian Navy in the 1980s until the next generation of surface ship was built. Encompassing all the classes based on the initial St. Laurent (the remaining St. Laurent, Restigouche, Mackenzie, and Annapolis-class vessels), the DELEX upgrades were meant to improve their ability to combat modern Soviet submarines,[8] and to allow them to continue to operate as part of NATO task forces.[9]

The DELEX refit for the Mackenzie class was the same for the Improved Restigouche-class vessels. This meant that the ships would receive the new tactical data system ADLIPS, new radars, new fire control and satellite navigation.[10] They exchanged the SQS-503 sonar for the newer SQS-505 model.[3]

They also received a triple mount for 12.75-inch (324 mm) torpedo tubes that would use the new Mk 46 homing torpedo.[3][10] The Mark 46 torpedo had a range of 12,000 yards (11,000 m) at over 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph)[10][11] with a high-explosive warhead weighing 96.8 pounds (43.9 kg).[12]

Construction and career

Yukon was ordered in 1957[2] and laid down on 25 October 1959 at Burrard Dry Dock Ltd., North Vancouver. She was launched on 27 July 1961 and commissioned into the RCN on 25 May 1963 with the classification number DDE 263.[13]

Though built on the west coast, Yukon immediately transferred to the east coast, sailing for Halifax, Nova Scotia on 27 July. She remained on the east coast for a year, where as part of the First Canadian Escort Squadron, Yukon escorted Queen Elizabeth II aboard HMY Britannia on visits to several Canadian port cities.[14] She returned to the Pacific in 1965.[13] She was largely used as a training ship following her transfer by the RCN and later in the CF under Maritime Forces Pacific.

In 1970, Yukon sailed with sister ship Mackenzie and the auxiliary vessel Provider on a training deployment throughout the Pacific, working with several navies and visiting Japan.[13] In February 1975 underwent a mid-life refit. Upon completion, the ship joined Training Group Pacific.[15] On 17 January 1983, Yukon collided with the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk, with Yukon reporting slight damage to her mast.[16] She underwent the DELEX refit at the Burrard Yarrow shipyard at Esquimalt, British Columbia from 28 May 1984 to 16 January 1985.[13] In 1986, Yukon was one of three Canadian vessels that took part in the Royal Australian Navy's 75th anniversary celebrations.[15] She was decommissioned from Maritime Command on 3 December 1993.[13]

As an artificial reef

The ship was initially purchased by the Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia anchored on the New Westminster docks for almost a year before it was bought for $250,000.[17] Yukon's hulk was purchased by the San Diego Oceans Foundation which towed her from CFB Esquimalt to San Diego, California in 2000. She was gutted and cleaned before being scuttled in 100 feet (30 m) of water in the Pacific Ocean at Sunken Harbor off Mission Bay in San Diego as an artificial reef on 15 July 2000.[18] However the day before she was to be scuttled, she flooded in rough weather and sank at the site on 14 July.[13] The explosive charges intended to sink her were still intact on board, and United States Navy SEALs were sent in to remove the charges. The wreck was off limits for weeks while this was being done.[17]

The ship ended up lying on her port side, with her masthead lying 60 feet (18 m) below the water instead of the planned 30 feet (9.1 m). This made recreational diving on the wreck much more difficult.[19] By December 2012, five people had died while diving on Yukon's wreck.[17]

The ship's bell of Yukon is currently located in the Yukon Legislative Building.[20]

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b Arbuckle, p. 131

- ^ a b Milner, pp. 223–224

- ^ a b c d e f Gardiner & Chumbley, p. 45

- ^ MacIntosh, Dave (16 November 1962). "Canadian Navy Geared to Fight Fastest Subs". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Gardiner & Chumbley, pp. 44–45

- ^ a b Macpherson and Barrie (2002), p. 256

- ^ Milner, p. 225

- ^ Milner, pp. 277–278

- ^ Gimblett, p. 179

- ^ a b c Milner, p. 278

- ^ "Mk 46 Torpedo". weaponsystems.net. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ "Fact File: Mk 46 torpedo". United States Navy. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Macpherson and Barrie (2002), p. 259

- ^ "Her Majesty accepts R.C. Navy destroyer escort for visit". Granby Leader-Mail. 9 September 1964. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b Barrie and Macpherson (1996), p. 57

- ^ "Destroyer escort nudges Kitty Hawk". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 17 January 1983. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Goetz, Russell (19 December 2012). "Why the Yukon will continue to kill divers". San Diego Reader. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Orrick, p. 11

- ^ Orrick, p. 15

- ^ "The Christening Bells Project". CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum. Archived from the original on December 30, 2009.

Sources

- Arbuckle, J. Graeme (1987). Badges of the Canadian Navy. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 0-920852-49-1.

- Barrie, Ron; Macpherson, Ken (1996). Cadillac of Destroyers: HMCS St. Laurent and Her Successors. St. Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-55125-036-5.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chumbley, Stephen; Budzbon, Przemysław, eds. (1995). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1947–1995. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-132-7.

- Gimblett, Richard H., ed. (2009). The Naval Service of Canada 1910–2010: The Centennial Story. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-4597-1322-2.

- Macpherson, Ken; Barrie, Ron (2002). The Ships of Canada's Naval Forces 1910–2002 (Third ed.). St. Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-55125-072-1.

- Milner, Marc (2010). Canada's Navy: The First Century (Second ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9604-3.

- Orrick, Bob (2010). RCN Reefs. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4535-1880-9.[self-published source?]