Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

| Golconda | |

|---|---|

| Hyderabad, India | |

| |

| Coordinates | 17°22′59″N 78°24′04″E / 17.38306°N 78.40111°E |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Controlled by | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 11th century |

| Built by | Kakatiya dynasty ruler King Prataparudra in the 11th century Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk (1518 fortification) |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Bahmani Sultanate, Golconda Sultanate, Mughal Empire |

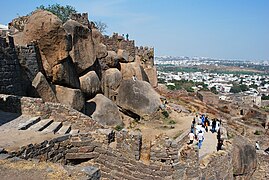

Golconda is a fortified citadel and ruined city located on the western outskirts of Hyderabad, Telangana, India.[1][2] The fort was originally built by Kakatiya ruler Pratāparudra in the 11th century out of mud walls.[3] It was ceded to the Bahmani Kings from Musunuri Nayakas during the reign of the Bahmani Sultan Mohammed Shah I, during the first Bahmani-Vijayanagar War. Following the death of Sultan Mahmood Shah, the Sultanate disintegrated and Sultan Quli, who had been appointed as the Governor of Hyderabad by the Bahmani Kings, fortified the city and made it the capital of the Golconda Sultanate. Because of the vicinity of diamond mines, especially Kollur Mine, Golconda flourished as a trade centre of large diamonds known as Golconda Diamonds. Golconda fort is currently abandoned and in ruins. The complex was put by UNESCO on its "tentative list" to become a World Heritage Site in 2014, with other forts in the region, under the name Monuments and Forts of the Deccan Sultanate (despite there being a number of different sultanates).[1]

History

The origins of the Golconda fort can be traced back to the 11th century. It was originally a small mud fort built by Pratāparudra of the Kakatiya Empire.[3] The name Golconda is thought to originate from the Telugu గొల్ల కొండ Golla koṇḍa for "Shepherd's hill".[4][5] It is also thought that Kakatiya ruler Ganapatideva 1199–1262 built a stone hilltop outpost — later known as Golconda fort — to defend their western region.[6] The fort was later developed into a fortified citadel in 1518 by Sultan Quli of the Qutb Shahi Empire and the city was declared the capital of the Golconda Sultanate.[5]

The Bahmani kings took possession of the fort after it was made over to them by means of a sanad by the Rajah of Warangal.[3] Under the Bahmani Sultanate, Golconda slowly rose to prominence. Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk (r. 1487–1543), sent by the Bahmanids as a governor at Golconda, established the city as the seat of his governance around 1501. Bahmani rule gradually weakened during this period, and Sultan Quli (Quli Qutub Shah period) formally became independent in 1518, establishing the Qutb Shahi dynasty based in Golconda.[7][8][9] Over a period of 62 years, the mud fort was expanded by the first three Qutb Shahi sultans into the present structure: a massive fortification of granite extending around 5 km (3.1 mi) in circumference. It remained the capital of the Qutb Shahi dynasty until 1590 when the capital was shifted to Hyderabad. The Qutb Shahis expanded the fort, whose 7 km (4.3 mi) outer wall enclosed the city.

During the early seventeenth century a strong cotton-weaving industry existed in Golconda. Large quantities of cotton were produced for domestic and exports consumption. High quality plain or patterned cloth made of muslin and calico was produced. Plain cloth was available as white or brown colour, in bleached or dyed variety. Exports of this cloth was to Persia and European countries. Patterned cloth was made of prints which were made indigenously with indigo for blue, chay-root for red coloured prints and vegetable yellow. Patterned cloth exports were mainly to Java, Sumatra and other eastern countries.[10] The fort finally fell into ruin in 1687 after an eight-month-long siege led to its fall at the hands of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, who ended the Qutb Shahi reign and took the last Golconda king, Abul Hassan Tana Shah, captive.[11][5]

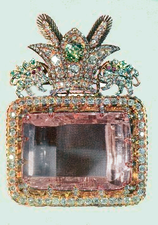

Diamonds

The Golconda fort used to have a vault where the famous Koh-i-Noor and Hope diamonds were once stored along with other diamonds.[12]

Golconda is renowned for the diamonds found on the south-east at Kollur Mine near Kollur, Guntur district, Paritala and Atkur in Krishna district and cut in the city during the Kakatiya reign. At that time, India had the only known diamond mines in the world. Golconda was the market city of the diamond trade, and gems sold there came from a number of mines. The fortress-city within the walls was famous for diamond trade.[citation needed]

Its name has taken a generic meaning and has come to be associated with great wealth. Some gemologists use this classification to denote the extremely rare Type IIa diamond, a crystal that essentially lacks nitrogen impurities and is therefore colorless; Many Type IIa diamonds, as identified by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), have come from the mines in and around the Golconda region.

Many famed diamonds are believed to have been excavated from the mines of Golconda, such as:

- Daria-i-Noor

- Noor-ul-Ain

- Koh-i-Noor

- Hope Diamond

- Princie Diamond

- Regent Diamond

- Wittelsbach-Graff Diamond

By the 1880s, "Golconda" was being used generically by English speakers to refer to any particularly rich mine, and later to any source of great wealth.

During the Renaissance and the early modern eras, the name "Golconda" acquired a legendary aura and became synonymous for vast wealth. The mines brought riches to the Qutb Shahis of Hyderabad State, who ruled Golconda up to 1687, then to the Nizam of Hyderabad, who ruled after the independence from the Mughal Empire in 1724 until 1948, when the Indian integration of Hyderabad occurred. The siege of Golconda occurred in January 1687, when Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb led his forces to besiege the Qutb Shahi dynasty at Golconda fort (also known as the Diamond Capitol of its time) and was home to the Kollur Mine. The ruler of Golconda was the well entrenched Abul Hasan Qutb Shah.[13]

The Golconda's Architecture

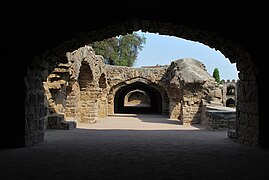

Golconda fort is listed as an archaeological treasure on the official "List of Monuments" prepared by the Archaeological Survey of India under The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act.[14] Golconda consists of four distinct forts with a 10 km (6.2 mi) long outer wall with 87 semicircular bastions (some still mounted with cannons), eight gateways, and four drawbridges, with a number of royal apartments and halls, temples, mosques, magazines, stables, etc. inside. The lowest of these is the outermost enclosure entered by the "Fateh Darwaza" (Victory gate, so called after Aurangzeb’s triumphant army marched in through this gate) studded with giant iron spikes (to prevent elephants from battering them down) near the south-eastern corner. An acoustic effect can be experienced at Fateh Darwazaan, a hand clap at a certain point below the dome at the entrance reverberates and can be heard clearly at the 'Bala Hisar' pavilion, the highest point almost a kilometer away. This worked as a warning in case of an attack.

Bala Hissar Gate is the main entrance to the fort located on the eastern side. It has a pointed arch bordered by rows of scroll work. The spandrels have yalis and decorated roundels. The area above the door has peacocks with ornate tails flanking an ornamental arched niche. The granite block lintel below has sculpted yalis flanking a disc. The design of peacocks and lions is typical of Hindu architecture and underlies this fort's Hindu origins.

Jagadamba temple, located next to Ibrahim mosque and the king's palace, is visited by lakhs of devotees during Bonalu festival every year.[15][16] Jagadamba temple is about 900 to 1,000 years old, dating back to early Kakatiya period.[17] A Mahankali temple is located in the vicinity, within Golconda fort.[18]

The fort also contains the tombs of the Qutub Shahi kings. These tombs have Islamic architecture and are located about 1 km (0.62 mi) north of the outer wall of Golconda. They are encircled by gardens and numerous carved stones.

The two individual pavilions on the outer side of Golconda are built on a point which is quite rocky. The "Kala Mandir" is also located in the fort. It can be seen from the king's durbar (king's court) which was on top of the Golconda fort.

The other buildings found inside the fort are: Habshi Kamans (Abyssian arches), Ashlah Khana, Taramati mosque, Ramadas Bandikhana, Camel stable, private chambers (kilwat), Mortuary bath, Nagina bagh, Ramasasa's kotha, Durbar hall, Ambar khana etc.

-

Rani Mahal

-

Fort overlooking the city of Hyderabad

-

Mosque of Ibrahim

-

Baradari located at the top of the citadel

-

Jagadamba temple at the top of the Golconda fortifications

-

Bala Hissar Darwaza

-

Mahankaali temple at Golconda, Hyderabad

-

View from the Baradari

-

Design inside the Golconda fort

-

Aerial view of Golconda fort

-

Cannon of the Golconda fort

-

Pathway in Golconda fort

-

Baradari fort

Golconda ruling dynasties

- Kakatiya dynasty

- Musunuri Nayakas

- Bahmani Sultans

- Qutb Shahi dynasty

- Mughal Empire

- Asaf Jahi dynasty

Naya Qila (New Fort)

Naya Qila is an extension of Golconda fort which was turned into the Hyderabad Golf Club despite resistance from farmers who owned the land and various NGOs within the city. The ramparts of the new fort start after the residential area with many towers and the Hatiyan ka Jhad ("Elephant-sized tree")—an ancient baobab tree with an enormous girth. It also includes a war mosque. These sites are under restrictive access to the public because of the Golf Course.

Qutub Shahi tombs

The tombs of the Qutub Shahi sultans lie about one kilometre north of Golconda's outer wall. These structures are made of beautifully carved stonework, and surrounded by landscaped gardens. They are open to the public and receive many visitors. It is one of the famous sight-seeing places in Hyderabad.

Golconda Artillery Centre, Indian Army

Golconda Artillery Centre, Hyderabad, was raised on 15 August 1962 as the Second Recruit Training Centre for the Regiment of Artillery.[19][20] Golconda Artillery Centre is located in and around the Golconda fort. The Golconda centre has three training regiments and presently trains 2900 recruits at a time.[21]

UNESCO World Heritage

The Golconda fort and other Qutb Shahi dynasty Monuments of Hyderabad (the Charminar, and the Qutb Shahi Tombs) were submitted by the Permanent Delegation of India to UNESCO in 2010 for consideration as World Heritage Sites. They are currently included on India's "tentative list".[22][23]

Influences

In popular culture

- Aline, reine de Golconde (1760), story by Stanislas de Boufflers

- Aline, reine de Golconde (1766), opera by Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny

- Aline, reine de Golconde (1803), opera by Henri-Montan Berton

- Aline, reine de Golconde (1804), opera by François-Adrien Boieldieu

- Alina, regina di Golconda (1828), opera by Gaetano Donizetti

- Drottningen av Golconda (The Queen of Golconda, 1863), Swedish-language opera by Franz Berwald

- Russell Conwell's book Acres of Diamonds tells a story of the discovery of the Golconda mines.

- René Magritte's painting Golconda was named after the city.

- John Keats' early poem "On receiving a curious Shell" opens with the lines: "Hast thou from the caves of Golconda, a gem / pure as the ice-drop that froze on the mountain?"[24]

- Golconda is referenced in the classical Russian ballet, La Bayadère (1877).

- Anthony Doerr's Pulitzer Prize–winning novel All the Light We Cannot See references the Golconda mines as the discovery place of the "Sea of Flames" diamond

- In Patrick O'Brian's novel The Surgeon's Mate, a character describes a particularly valuable diamond as being worth "half Golconda".

- The term 'Golconda' is used in White Wolf's Vampire: the Masquerade table-top role-playing game to refer to a mystical state of enlightenment. Pursuit of Golconda is usually the ultimate aim of a campaign, although what this might entail is largely left to the storyteller's discretion.

Places named after Golconda

- A city in Illinois, United States is named after Golconda.

- A city in Nevada, United States is named after Golconda.

- A village located in the southern part of Trinidad had given the name in the 19th century to a rich tract of land which was once a sugar-cane estate. Currently, mostly descendants of East Indian indentured servants occupy the village of Golconda.

Gallery

-

Golconda Fort—Large View

-

Golconda Fort seen from a road

-

Stone Arch Ruins

-

Golkonda during light show at night

-

Fort overlooking the city

-

Staircase leading to the top of the Fort

-

Ambar Khana

-

Rani Mahal

-

Taramati Mosque

-

Golconda fort inside view

-

Architecture inside Golconda fort

-

Golconda fort from inside

-

View of the Golconda fort

-

Golconda fort from outside

See also

- Afanasiy Nikitin – the first European to visit Golconda

- History of Hyderabad

- Naya Qila

- Taramati Baradari

Citations

- ^ a b UNESCO "tentative list"

- ^ "How an impregnable fort city was finally breached by treachery". 29 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Bilgrami, S.A. Asgar (1927). The Landmarks of the Deccan. Hyderabad-Deccan. pp. 108–110. ISBN 9789353245733.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Harin Chandra (14 May 2012). "Enjoy a slice of history". The Hindu.

- ^ a b c Lasania, Yunus (19 February 2022). "Hyderabad: How rumours of a secret tunnel are ruining the Charminar". The Siasat Daily. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Yimene, Ababu Minda (2004). An African Indian community in Hyderabad. Cuvillier Verlag. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-86537-206-2. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Sherwani, H.K. (1974). The History of the Qutb Shahi Dynasty. India: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788121503396.

- ^ Sardar, Marika (2007). Golconda Through Time: A Mirror of the Evolving Deccan (PhD thesis). New York University. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-549-10119-2.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ Moreland, W.H (1931). Relation of Golconda in the Early Seventeenth Century. Halyukt Society.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 178.

- ^ Bradnock, Roma (2007). Footprint India. Footprint. p. 1035. ISBN 978-1-906098-05-6.

- ^ "Delving into the rich and often bloody history of Golconda Fort". The Hindu. 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Alphabetical List of Monuments – Andhra Pradesh". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ "Historic Jagadamba temple sees many devotees, but few facilities". The Times of India. 30 October 2017.

- ^ "Golconda Bonalu begins with religous [sic] fervour". The Hindu. 30 June 2022.

- ^ "With pandemic on ebb, state gears up for grand Bonalu". 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Golconda Mahankali temple set for grand Bonalu fete". 15 June 2022.

- ^ "830 new recruits pass out from Artillery Centre". The Times of India. 28 March 2021.

- ^ "First batch of Agniveers start training at Golconda Artillery in Hyderabad". The Times of India. 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Arty Centre, Hyderabad". Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Qutb Shahi Monuments of Hyderabad Golconda Fort, Qutb Shahi Tombs, Charminar – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ Archana Khare Ghose. "Prestige or Preservation?". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ "6. On receiving a curious Shell. Keats, John. 1884. The Poetical Works of John Keats". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

Further reading

- Prasad, G. Durga (1988). History of the Andhras up to 1565 A. D. (PDF). Guntur: P. G. Publishers.

- Nanisetti, Serish (2019). Golconda Bagnagar Hyderabad, Rise and Fall of a Global Metropolis in Medieval India (1st ed.). Generic. ISBN 9789353518813.

External links

- Qutb Shahi Architecture at Golconda (archived 18 May 2015)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.