Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2H-Chromen-2-one

| |

| Preferred IUPAC name

2H-1-Benzopyran-2-one | |

| Other names

1-Benzopyran-2-one

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 383644 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.897 |

| EC Number |

|

| 165222 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H6O2 | |

| Molar mass | 146.145 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless to white crystals |

| Odor | pleasant, like vanilla beans |

| Density | 0.935 g/cm3 (20 °C (68 °F)) |

| Melting point | 71 °C (160 °F; 344 K) |

| Boiling point | 301.71 °C (575.08 °F; 574.86 K) |

| 0.17 g / 100 mL | |

| Solubility | very soluble in ether, diethyl ether, chloroform, oil, pyridine soluble in ethanol |

| log P | 1.39 |

| Vapor pressure | 1.3 hPa (106 °C (223 °F)) |

| −82.5×10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| orthorhombic | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302, H317, H373 | |

| P260, P261, P264, P270, P272, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P314, P321, P330, P333+P313, P363, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 150 °C (302 °F; 423 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

293 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Chromone; 2-Cumaranone |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

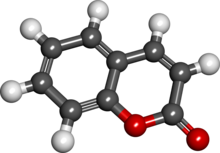

Coumarin (/ˈkuːmərɪn/) or 2H-chromen-2-one is an aromatic organic chemical compound with formula C9H6O2. Its molecule can be described as a benzene molecule with two adjacent hydrogen atoms replaced by an unsaturated lactone ring −(CH)=(CH)−(C=O)−O−, forming a second six-membered heterocycle that shares two carbons with the benzene ring. It belongs to the benzopyrone chemical class and considered as a lactone.[1]

Coumarin is a colorless crystalline solid with a sweet odor resembling the scent of vanilla and a bitter taste.[1] It is found in many plants, where it may serve as a chemical defense against predators. Coumarin inhibits synthesis of vitamin K, a key component in blood clotting. A related compound, the prescription drug anticoagulant warfarin, is used to inhibit formation of blood clots, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.[1][2]

Etymology

Coumarin is derived from coumarou, the French word for the tonka bean, from the Old Tupi word for its tree, kumarú.[3]

History

Coumarin was first isolated from tonka beans in 1820 by A. Vogel of Munich, who initially mistook it for benzoic acid.[4][5]

Also in 1820, Nicholas Jean Baptiste Gaston Guibourt (1790–1867) of France independently isolated coumarin, but he realized that it was not benzoic acid.[6] In a subsequent essay he presented to the pharmacy section of the Académie Royale de Médecine, Guibourt named the new substance coumarine.[7][8]

In 1835, the French pharmacist A. Guillemette proved that Vogel and Guibourt had isolated the same substance.[9] Coumarin was first synthesized in 1868 by the English chemist William Henry Perkin.[10]

Coumarin has been an integral part of the fougère genre of perfume since it was first used in Houbigant's Fougère Royale in 1882.[11]

Synthesis

Coumarin can be prepared by a number of name reactions, with the Perkin reaction between salicylaldehyde and acetic anhydride being a popular example. The Pechmann condensation provides another route to coumarin and its derivatives starting from phenol, as does the Kostanecki acylation,[12] which can also be used to produce chromones.

Biosynthesis

From lactonization of ortho-hydroxylated cis-hydroxycinnamic acid.[13]

Natural occurrence

Coumarin is found naturally in many plants. Freshly ground plant parts contain higher amount of desired and undesired phytochemicals than powder. In addition, whole plant parts are harder to counterfeit; for example, one study showed that authentic Ceylon cinnamon bark contained 0.012 to 0.143 mg/g coumarin, but samples purchased at markets contained up to 3.462 mg/g, possibly because those were mixed with other cinnamon varieties.[14]

- Vanilla grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum)

- Sweet woodruff (Galium odoratum)

- Sweet grass (Hierochloe odorata)

- Sweet-clover (genus Melilotus)

- Meranti trees (genus Shorea)

- Tonka bean (Dipteryx odorata)

- Cinnamon; a 2013 study showed different varieties containing different levels of coumarin:[15]

- Ceylon cinnamon or true cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum): 0.005 to 0.090 mg/g

- Chinese cinnamon or Chinese cassia (C. cassia): 0.085 to 0.310 mg/g

- Indonesian cinnamon or Padang cassia (C. burmannii): 2.14 to 9.30 mg/g

- Saigon cinnamon or Vietnamese cassia (C. loureiroi): 1.06 to 6.97 mg/g

- Deertongue (Carphephorus odoratissimus),[16]

- Tilo (Justicia pectoralis),[17][18]

- Mullein (genus Verbascum)

- Many cherry blossom tree varieties (of the genus Prunus).[19]

- Related compounds are found in some but not all specimens of genus Glycyrrhiza, from which the root and flavour licorice derives.[20]

Coumarin is found naturally also in many edible plants such as strawberries, black currants, apricots, and cherries.[1]

Coumarins were found to be uncommon but occasional components of propolis by Santos-Buelga and Gonzalez-Paramas 2017.[21]

Biological function

Coumarin has appetite-suppressing properties, which may discourage animals from eating plants that contain it. Though the compound has a pleasant sweet odor, it has a bitter taste, and animals tend to avoid it.[22]

Metabolism

The biosynthesis of coumarin in plants is via hydroxylation, glycolysis, and cyclization of cinnamic acid.[citation needed] In humans, the enzyme encoded by the gene UGT1A8 has glucuronidase activity with many substrates, including coumarins.[23]

Derivatives

Coumarin is used in the pharmaceutical industry as a precursor reagent in the synthesis of a number of synthetic anticoagulant pharmaceuticals similar to dicoumarol.[1] 4-hydroxycoumarins are a type of vitamin K antagonist.[1] They block the regeneration and recycling of vitamin K.[1][24] These chemicals are sometimes also incorrectly referred to as "coumadins" rather than 4-hydroxycoumarins. Some of the 4-hydroxycoumarin anticoagulant class of chemicals are designed to have high potency and long residence times in the body, and these are used specifically as rodenticides ("rat poison").[1] Death occurs after a period of several days to two weeks, usually from internal hemorrhaging.

Uses

Coumarin is often found in artificial vanilla substitutes, despite having been banned as a food additive in numerous countries since the mid-20th century. It is still used as a legal flavorant in soaps, rubber products, and the tobacco industry,[1] particularly for sweet pipe tobacco and certain alcoholic drinks.[which?][citation needed]

Toxicity

Coumarin is moderately toxic to the liver and kidneys of rodents, with a median lethal dose (LD50) of 293 mg/kg in the rat,[25] a low toxicity compared to related compounds. Coumarin is hepatotoxic in rats, but less so in mice. Rodents metabolize it mostly to 3,4-coumarin epoxide, a toxic, unstable compound that on further differential metabolism may cause liver cancer in rats and lung tumors in mice.[26][27] Humans metabolize it mainly to 7-hydroxycoumarin, a compound of lower toxicity, and no adverse affect has been directly measured in humans.[28] The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment has established a tolerable daily intake (TDI) of 0.1 mg coumarin per kg body weight, but also advises that higher intake for a short time is not dangerous.[29] The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) of the United States does not classify coumarin as a carcinogen for humans.[30]

European health agencies have warned against consuming high amounts of cassia bark, one of the four main species of cinnamon, because of its coumarin content.[31][32] According to the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BFR), 1 kg of (cassia) cinnamon powder contains about 2.1 to 4.4 g of coumarin.[33] Powdered cassia cinnamon weighs 0.56 g/cm3,[34] so a kilogram of cassia cinnamon powder equals 362.29 teaspoons. One teaspoon of cassia cinnamon powder therefore contains 5.8 to 12.1 mg of coumarin, which may be above the tolerable daily intake value for smaller individuals.[33] However, the BFR only cautions against high daily intake of foods containing coumarin. Its report specifically states that Ceylon cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) contains "hardly any" coumarin.[33]

The European Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 describes the following maximum limits for coumarin: 50 mg/kg in traditional and/or seasonal bakery ware containing a reference to cinnamon in the labeling, 20 mg/kg in breakfast cereals including muesli, 15 mg/kg in fine bakery ware, with the exception of traditional and/or seasonal bakery ware containing a reference to cinnamon in the labeling, and 5 mg/kg in desserts.

An investigation from the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration in 2013 shows that bakery goods characterized as fine bakery ware exceeds the European limit (15 mg/kg) in almost 50% of the cases.[35] The paper also mentions tea as an additional important contributor to the overall coumarin intake, especially for children with a sweet habit.

Coumarin was banned as a food additive in the United States in 1954, largely because of the hepatotoxicity results in rodents.[36] Coumarin is currently listed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States among "Substances Generally Prohibited From Direct Addition or Use as Human Food," according to 21 CFR 189.130,[37][38] but some natural additives containing coumarin, such as the flavorant sweet woodruff are allowed "in alcoholic beverages only" under 21 CFR 172.510.[39] In Europe, popular examples of such beverages are Maiwein, white wine with woodruff, and Żubrówka, vodka flavoured with bison grass.

Coumarin is subject to restrictions on its use in perfumery,[40] as some people may become sensitized to it, however the evidence that coumarin can cause an allergic reaction in humans is disputed.[41]

Minor neurological dysfunction was found in children exposed to the anticoagulants acenocoumarol or phenprocoumon during pregnancy. A group of 306 children were tested at ages 7–15 years to determine subtle neurological effects from anticoagulant exposure. Results showed a dose–response relationship between anticoagulant exposure and minor neurological dysfunction. Overall, a 1.9 (90%) increase in minor neurological dysfunction was observed for children exposed to these anticoagulants, which are collectively referred to as "coumarins." In conclusion, researchers stated, "The results suggest that coumarins have an influence on the development of the brain which can lead to mild neurologic dysfunctions in children of school age."[42]

Coumarin's addition to cigarette tobacco by Brown & Williamson caused executive[43] Dr. Jeffrey Wigand to contact CBS's news show 60 Minutes in 1995, charging that a "form of rat poison" was being used as an additive. He held that from a chemist’s point of view, coumarin is an "immediate precursor" to the rodenticide (and prescription drug) coumadin.[2] Dr. Wigand later stated that coumarin itself is dangerous, pointing out that the FDA had banned its addition to human food in 1954.[44] Under his later testimony, he would repeatedly classify coumarin as a "lung-specific carcinogen."[45] In Germany, coumarin is banned as an additive in tobacco.

Alcoholic beverages sold in the European Union are limited to a maximum of 10 mg/L coumarin by law.[46] Cinnamon flavor is generally cassia bark steam-distilled to concentrate the cinnamaldehyde, for example, to about 93%. Clear cinnamon-flavored alcoholic beverages generally test negative for coumarin, but if whole cassia bark is used to make mulled wine, then coumarin shows up at significant levels.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Coumarin". PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Coumarins and indandiones". Drugs.com. 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Warfarin, Molecule of the Month for February 2011, by John Maher". www.chm.bris.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ^ Vogel, A. (1820). "Darstellung von Benzoesäure aus der Tonka-Bohne und aus den Meliloten- oder Steinklee-Blumen" [Preparation of benzoic acid from tonka beans and from the flowers of melilot or sweet clover]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 64 (2): 161–166. Bibcode:1820AnP....64..161V. doi:10.1002/andp.18200640205.

- ^ Vogel, A. (1820). "De l'existence de l'acide benzoïque dans la fève de tonka et dans les fleurs de mélilot" [On the existence of benzoic acid in the tonka bean and in the flowers of melilot]. Journal de Pharmacie (in French). 6: 305–309.

- ^ Guibourt, N. J. B. G. (1820). Histoire Abrégée des Drogues Simples [Abridged History of Simple Drugs] (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: L. Colas. pp. 160–161.

- ^ "Societe du Pharmacie de Paris". Journal de Chimie Médicale, de Pharmacie et de Toxicologie. 1: 303. 1825.

... plus récemment, dans un essai de nomenclature chimique, lu à la section de Pharmacie de l'Académie royale de Médecine, il l'a désignée sous le nom de coumarine, tiré du nom du végétal coumarouna odorata ... [... more recently, in an essay on chemical nomenclature, [which was] read to the pharmacy section of the Royal Academy of Medicine, he [Guibourt] designated it by the name "coumarine," derived from the name of the vegetable Coumarouna odorata ...]

- ^ Guibourt, N. J. B. G. (1869). Histoire Naturelle des Drogues Simples (6th ed.). Paris: J. B. Baillière et fils. p. 377.

... la matière cristalline de la fève tonka (matière que j'ai nommée coumarine) ... [... the crystalline matter of the tonka bean (matter that I named coumarine ...]

- ^ Guillemette, A. (1835). "Recherches sur la matière cristalline du mélilot" [Research into the crystalline material of melilot]. Journal de Pharmacie. 21: 172–178.

- ^ Perkin, W. H. (1868). "On the artificial production of coumarin and formation of its homologues". Journal of the Chemical Society. 21: 53–63. doi:10.1039/js8682100053.

- ^ "Olfactory Groups - Aromatic Fougere". fragrantica.com. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Sethna, S. M.; Shah, N. M. (1945). "The Chemistry of Coumarins". Chemical Reviews. 36: 1–62. doi:10.1021/cr60113a001.

- ^ Jacobowitz, Joseph R.; Weng, Jing-Ke (2020-04-29). "Exploring Uncharted Territories of Plant Specialized Metabolism in the Postgenomic Era". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 71 (1). Annual Reviews: 631–658. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-081519-035634. ISSN 1543-5008. PMID 32176525. S2CID 212740956.

- ^ Ananthakrishnan, R.; Chandra, Preeti; Kumar, Brijesh; Rameshkumar, K. B. (1 January 2018). "Quantification of coumarin and related phenolics in cinnamon samples from south India using UHPLC-ESI-QqQLIT-MS/MS method". International Journal of Food Properties. 21: 50–57. doi:10.1080/10942912.2018.1437629. S2CID 104289832.

- ^ Cassia Cinnamon as a Source of Coumarin in Cinnamon-Flavored Food and Food Supplements in the United States J. Agric. Food Chem., 61 (18), 4470–4476

- ^ Khan, Ikhlas A.; Ehab, Abourashed A. (2010). Leung's Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients Used in Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics (PDF). Hoboken, NJ USA: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 240–242. ISBN 978-9881607416. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Leal, L. K. A. M.; Ferreira, A. A. G.; Bezerra, G. A.; Matos, F. J. A.; Viana, G. S. B. (May 2000). "Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator activities of Brazilian medicinal plants containing coumarin: a comparative study". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 70 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00165-8. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 10771205.

- ^ Lino, C. S.; Taveira, M. L.; Viana, G. S. B.; Matos, F. J. A. (1997). "Analgesic and antiinflammatory activities of Justicia pectoralis Jacq. and its main constituents: coumarin and umbelliferone". Phytotherapy Research. 11 (3): 211–215. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199705)11:3<211::AID-PTR72>3.0.CO;2-W. S2CID 84525194. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^ Ieri, Francesca; Pinelli, Patrizia; Romani, Annalisa (2012). "Simultaneous determination of anthocyanins, coumarins and phenolic acids in fruits, kernels and liqueur of Prunus mahaleb L". Food Chemistry. 135 (4): 2157–2162. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.083. hdl:2158/775163. PMID 22980784. S2CID 14467019.

- ^ Hatano, T.; et al. (1991). "Phenolic constituents of licorice. IV. Correlation of phenolic constituents and licorice specimens from various sources, and inhibitory effects of..." Yakugaku Zasshi. 111 (6): 311–21. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.111.6_311. PMID 1941536.

- ^ Berenbaum, May R.; Calla, Bernarda (2021-01-07). "Honey as a Functional Food for Apis mellifera". Annual Review of Entomology. 66 (1). Annual Reviews: 185–208. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-040320-074933. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 32806934. S2CID 221165130.

- ^ Link, K. P. (1 January 1959). "The discovery of dicumarol and its sequels". Circulation. 19 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.19.1.97. PMID 13619027.

- ^ Ritter, J. K.; et al. (Mar 1992). "A novel complex locus UGT1 encodes human bilirubin, phenol, and other UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isozymes with identical carboxyl termini". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (5): 3257–3261. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50724-4. PMID 1339448.

- ^ "Warfarin". Drugs.com. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ Coumarin Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) Archived 2004-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vassallo, J. D.; et al. (2004). "Metabolic detoxification determines species differences in coumarin-induced hepatotoxicity". Toxicological Sciences. 80 (2): 249–57. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfh162. PMID 15141102.

- ^ Born, S. L.; et al. (2003). "Comparative metabolism and kinetics of coumarin in mice and rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 41 (2): 247–58. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00227-2. PMID 12480300.

- ^ Lake, B.G (1999). "Coumarin Metabolism, Toxicity and Carcinogenicity: Relevance for Human Risk Assessment". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 37 (4): 423–453. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00010-1. PMID 10418958.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about coumarin in cinnamon and other foods" (PDF). The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. 30 October 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Chemical Sampling Information – Coumarin". Osha.gov. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Cassia cinnamon with high coumarin contents to be consumed in moderation - BfR". Bfr.bund.de. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "German Christmas Cookies Pose Health Danger". NPR.org. 25 December 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ a b c "High daily intakes of cinnamon: Health risk cannot be ruled out. BfR Health Assessment No. 044/2006, 18 August 2006" (PDF). bund.de. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Engineering Resources – Bulk Density Chart Archived 2002-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ballin, Nicolai Z.; Sørensen, Ann T. (April 2014). "Coumarin content in cinnamon containing food products on the Danish market". Food Control. 38 (2014): 198–203. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.10.014.

- ^ Marles, R. J.; et al. (1986). "Coumarin in vanilla extracts: Its detection and significance". Economic Botany. 41 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1007/BF02859345. S2CID 23232507.

- ^ "Food and Drugs". Access.gpo.gov. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "FDA/CFSAN/OPA: EAFUS List". www.cfsan.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 3 September 2000. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Food and Drugs". Access.gpo.gov. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Standards Restricted - IFRA International Fragrance Association". Archived from the original on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ "Cropwatch Claims Victory Regarding "26 Allergens" Legislation : Modified from article originally written for Aromaconnection, Feb 2008" (PDF). Leffingwell.com. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Wessling, J. (2001). "Neurological outcome in school-age children after in utero exposure to coumarins". Early Human Development. 63 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1016/S0378-3782(01)00140-2. PMID 11408097.

- ^ "Jeffrey Wigand : Jeffrey Wigand on 60 Minutes". Jeffreywigand.com. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Tobacco On Trial". Tobacco-on-trial.com. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Industry Documents Library". Legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Wang, YH; Avula, B.; Zhao, J.; Smillie, TJ; Nanayakkara, NPD; Khan, IA (2010). "Characterization and Distribution of Coumarin, Cinnamaldehyde and Related Compounds in Cinnamomum spp. by UPLC-UV/MS Combined with PCA". Planta Medica. 76 (5). doi:10.1055/s-0030-1251793.