Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

Archdiocese of Carthage Archidioecesis Carthaginensis | |

|---|---|

| Bishopric | |

Early Christian quarter in ancient Carthage | |

| Incumbent: Cyriacus of Carthage (last residing ca. 1070) Agostino Casaroli (last titular archbishop 1979) | |

| Location | |

| Country | Roman Empire Vandal Kingdom Byzantine Empire Umayyad Caliphate Abbasid Caliphate Fatimid Caliphate French protectorate of Tunisia Tunisia |

| Ecclesiastical province | Early African church |

| Metropolitan | Carthage |

| Headquarters | Carthage |

| Coordinates | 36°51′10″N 10°19′24″E / 36.8528°N 10.3233°E) |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | African Rite |

| Established | 2nd century |

| Dissolved | In partibus infidelium in 1519 |

| Leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Titular archbishop | Vacant since 1979 |

The Archdiocese of Carthage, also known as the Church of Carthage, was a Latin Catholic diocese established in Carthage, Roman Empire, in the 2nd century. Agrippin was the first named bishop, around 230 AD. The temporal importance of the city of Carthage in the Roman Empire had previously been restored by Julius Caesar and Augustus. When Christianity became firmly established around the Roman province of Africa Proconsulare, Carthage became its natural ecclesiastical seat.[1] Carthage subsequently exercised informal primacy as an archdiocese, being the most important center of Christianity in the whole of Roman Africa, corresponding to most of today's Mediterranean coast and inland of Northern Africa. As such, it enjoyed honorary title of patriarch as well as primate of Africa: Pope Leo I confirmed the primacy of the bishop of Carthage in 446: "Indeed, after the Roman Bishop, the leading Bishop and metropolitan for all Africa is the Bishop of Carthage."[2][3][4]

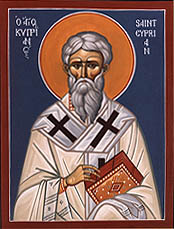

The Church of Carthage thus was to the Early African church what the Church of Rome was to the Catholic Church in Italy.[5] The archdiocese used the African Rite, a variant of the Western liturgical rites in Latin language, possibly a local use of the primitive Roman Rite. Famous figures include Saint Perpetua, Saint Felicitas, and their Companions (died c. 203), Tertullian (c. 155–240), Cyprian (c. 200–258), Caecilianus (floruit 311), Saint Aurelius (died 429), and Eugenius of Carthage (died 505). Tertullian and Cyprian are both considered Latin Church Fathers of the Latin Church. Tertullian, a theologian of part Berber descent, was instrumental in the development of trinitarian theology, and was the first to apply Latin language extensively in his theological writings. As such, Tertullian has been called "the father of Latin Christianity"[6][7] and "the founder of Western theology."[8] Carthage remained an important center of Christianity, hosting several councils of Carthage.

In the 6th century, turbulent controversies in teachings affected the diocese: Donatism, Arianism, Manichaeism, and Pelagianism. Some proponents established their own parallel hierarchies.

The city of Carthage fell to the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb with the Battle of Carthage (698). The episcopal see remained but Christianity declined under persecution. The last resident bishop, Cyriacus of Carthage, was documented in 1076.

In 1518, the Archdiocese of Carthage was revived as a Catholic titular see. It was briefly restored as a residential episcopal see 1884–1964, after which it was supplanted by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tunis. The last titular archbishop, Agostino Casaroli, remained in office until 1979. Subsequent to this, the titular see has remained vacant.

History

Antiquity

Earliest bishops

In Christian traditions, some accounts give as the first bishop of Carthage Crescens, ordained by Saint Peter, or Speratus, one of the Scillitan Martyrs.[9] Epenetus of Carthage is found in Pseudo-Dorotheus and Pseudo-Hippolytus lists of seventy disciples.[10] The account of the martyrdom of Saint Perpetua and her companions in 203 mentions an Optatus who is generally taken to have been bishop of Carthage, but who may instead have been bishop of Thuburbo Minus. The first certain historically documented bishop of Carthage is Agrippinus around the 230s.[11] Also historically certain is Donatus, the immediate predecessor of Cyprian (249–258).[9][12][13][14][15]

Primacy

In the 3rd century, at the time of Cyprian, the bishops of Carthage exercised a real though not formalized primacy in the Early African Church.[16] not only in the Roman province of Proconsular Africa in the broadest sense (even when it was divided into three provinces through the establishment of Byzacena and Tripolitania), but also, in some supra-metropolitan form, over the Church in Numidia and Mauretania. The provincial primacy was associated with the senior bishop in the province rather than with a particular see and was of little importance in comparison to the authority of the bishop of Carthage, who could be appealed to directly by the clergy of any province.[16]

Division

Cyprian faced opposition within his own diocese over the question of the proper treatment of the lapsi who had fallen away from the Christian faith under persecution.[17]

More than eighty bishops, some from distant frontier regions of Numidia, attended the Council of Carthage (256).

A division in the church that came to be known as the Donatist controversy began in 313 among Christians in North Africa. The Donatists stressed the holiness of the church and refused to accept the authority to administer the sacraments of those who had surrendered the scriptures when they were forbidden under the Emperor Diocletian. The Donatists also opposed the involvement of Emperor Constantine in church affairs in contrast to the majority of Christians who welcomed official imperial recognition.

The occasionally violent controversy has been characterized as a struggle between opponents and supporters of the Roman system. The most articulate North African critic of the Donatist position, which came to be called a heresy, was Augustine, bishop of Hippo Regius. Augustine maintained that the unworthiness of a minister did not affect the validity of the sacraments because their true minister was Christ. In his sermons and books Augustine, who is considered a leading exponent of Christian dogma, evolved a theory of the right of orthodox Christian rulers to use force against schismatics and heretics. Although the dispute was resolved by a decision of an imperial commission in the Council of Carthage (411),[9] Donatist communities continued to exist as late as the 6th century.

Successors of Cyprian until before the Vandal invasion

The immediate successors of Cyprian were Lucianus and Carpophorus, but there is disagreement about which of the two was earlier. A bishop Cyrus, mentioned in a lost work by Augustine, is placed by some before, by others after, the time of Cyprian. There is greater certainty about the 4th-century bishops: Mensurius, bishop by 303, succeeded in 311 by Caecilianus, who was at the First Council of Nicaea and who was opposed by the Donatist bishop Majorinus (311–315). Rufus participated in an anti-Arian council held in Rome in 337 or 340 under Pope Julius I. He was opposed by Donatus Magnus, the true founder of Donatism. Gratus (344– ) was at the Council of Sardica and presided over the Council of Carthage (349). He was opposed by Donatus Magnus and, after his exile and death, by Parmenianus, whom the Donatists chose as his successor. Restitutus accepted the Arian formula at the Council of Rimini in 359 but later repented. Genethlius presided over two councils at Carthage, the second of which was held in 390.

By the end of the 4th century, the settled areas had become Christianized, and some Berber tribes had converted en masse.

The next bishop was Saint Aurelius, who in 421 presided over another council at Carthage and was still alive in 426. His Donatist opponent was Primianus, who had succeeded Parmenianus in about 391.[9] A dispute between Primian and Maximian, a relative of Donatus, resulted in the largest Maximian schism within the Donatist movement.

Bishops under the Vandals

Capreolus was bishop of Carthage when the Vandals conquered the province. Unable for that reason to attend the Council of Ephesus in 431 as chief bishop of Africa, he sent his deacon Basula or Bessula to represent him. In about 437, he was succeeded by Quodvultdeus, whom Gaiseric exiled and who died in Naples. A 15-year vacancy followed, and it was only in 454 that Saint Deogratias was ordained bishop of Carthage. He died at the end of 457 or the beginning of 458, and Carthage remained without a bishop for another 24 years. Saint Eugenius was consecrated in around 481, exiled, along with other Catholic bishops, by Huneric in 484, recalled in 487, but in 491 forced to flee to Albi in Gaul, where he died. When the Vandal persecution ended in 523, Bonifacius became bishop of Carthage and held a Council in 525.[9]

Middle Ages

Praetorian prefecture of Africa

The Eastern Roman Empire established its praetorian prefecture of Africa after the reconquest of northwestern Africa during the Vandalic War 533–534. Bonifacius was succeeded by Reparatus, who held firm in the Three Chapters Controversy and in 551 was exiled to Pontus, where he died. He was replaced by Primosus, who accepted the emperor's wishes on the controversy. He was represented at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 by the bishop of Tunis. Publianus was bishop of Carthage from before 566 to after 581. Dominicus is mentioned in letters of Pope Gregory the Great between 592 and 601. Fortunius lived at the time of Pope Theodore I (c. 640) and went to Constantinople in the time of Patriarch Paul II of Constantinople (641 to 653). Victor became bishop of Carthage in 646.

Islamic conquest of Mahgreb

Last resident bishops

At the beginning of the 8th century and at the end of the 9th, Carthage still appears in lists of dioceses over which the Patriarch of Alexandria claimed jurisdiction.

Two letters of Pope Leo IX on 27 December 1053 show that the diocese of Carthage was still a residential see. The texts are given in the Patrologia Latina of Migne.[18] They were written in reply to consultations regarding a conflict between the bishops of Carthage and Gummi about who was to be considered the metropolitan, with the right to convoke a synod. In each of the two letters, the pope laments that, while in the past Carthage had had a church council of 205 bishops, the number of bishops in the whole territory of Africa was now reduced to five, and that, even among those five, there was jealousy and contention. However, he congratulated the bishops to whom he wrote for submitting the question to the Bishop of Rome, whose consent was required for a definitive decision. The first of the two letters (Letter 83 of the collection) is addressed to Thomas, Bishop of Africa, whom Mesnages deduces to have been the bishop of Carthage.[9]: p. 8 The other letter (Letter 84 of the collection) is addressed to Bishops Petrus and Ioannes, whose sees are not mentioned, and whom the pope congratulates for having supported the rights of the see of Carthage.

In each of the two letters, Pope Leo declares that, after the Bishop of Rome, the first archbishop and chief metropolitan of the whole of Africa is the bishop of Carthage,[19] while the bishop of Gummi, whatever his dignity or power, will act, except for what concerns his own diocese, like the other African bishops, by consultation with the archbishop of Carthage. In the letter addressed to Petrus and Ioannes, Pope Leo adds to his declaration of the position of the bishop of Carthage the eloquent[20] declaration: "... nor can he, for the benefit of any bishop in the whole of Africa lose the privilege received once for all from the holy Roman and apostolic see, but he will hold it until the end of the world as long as the name of our Lord Jesus Christ is invoked there, whether Carthage lie desolate or whether it some day rise glorious again".[21] When in the 19th century the residential see of Carthage was for a while restored, Cardinal Charles-Martial-Allemand Lavigerie had these words inscribed in letters of gold beneath the dome of his great cathedral.[22] The building now belongs the Tunisian state and is used for concerts.

Later, an archbishop of Carthage named Cyriacus was imprisoned by the Arab rulers because of an accusation by some Christians. Pope Gregory VII wrote him a letter of consolation, repeating the hopeful assurances of the primacy of the Church of Carthage, "whether the Church of Carthage should still lie desolate or rise again in glory". By 1076, Cyriacus was set free, but there was only one other bishop in the province. These are the last of whom there is mention in that period of the history of the see.[23][24]

Decline

After the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, the church gradually died out along with the local Latin dialect. The Islamization of Christian appears to have been quick and the Arab authors paid scant attention to them. Christian graves inscribed with Latin and dated to 10th–11th centuries are known. By the end of 10th century, the number of bishoprics in the Maghreb region was 47 including 10 in southern Tunisia. In 1053, Pope Leo IX commented that only five bishoprics were left in Africa.[25]

Some primary accounts including Arabic ones in 10th century mention persecutions of the Church and measures undertaken by Muslim rulers to suppress it. A schism among the African churches developed by the time of Pope Formosus. In 980, Christians of Carthage contacted Pope Benedict VII, asking to declare Jacob as an archbishop. Leo IX declared the bishop of Carthage as the "first archbishop and metropolitan of all Africa" when a bishop of Gummi in Byzacena declared the region a metropolis. By the time of Gregory VII, the Church was unable to appoint a bishop which traditionally would have only required presence of three other bishops. This was likely due to persecutions and possibly other churches breaking off their communion with Carthage. In 1152, the Muslim rulers ordered the Christians of Tunisia to convert or face death. The only African bishopric mentioned in a list in 1192 published by the Catholic Church in Rome was that of Carthage.[26] Native Christianity is attested in the 15th century, though it was not in communion in with the Catholic church.[27]

The bishop of Morocco Lope Fernandez de Ain was made the head of the Church of Africa, the only church officially allowed to preach in the continent, on 19 December 1246 by Pope Innocent IV.[28]

List of bishops

- Crescentius (c. 80)

- Epenetus (c. 115)

- Speratus (180)

- Optatus (203)

- Agrippinus (c. 240)

- Donatus I (?–248)

- Cyprian (248–258)

- Maximus (251), Novatianist anti-bishop

- Fortunatus (252), anti-bishop

- Lucianus (3rd century)

- Carpophorus (3rd century)

- Cyrus (3rd century)

- Caecilianus (311–325)

- Majorinus (312 – c. 313), Donatist bishop

- Donatus II (c. 313 – c. 350×355), Donatist bishop

- Rufus (337×340)

- Gratus (fl. 343/4–345×348)

- Parmenianus (c. 350×355 – c. 391), Donatist bishop

- Restitutus (359)

- Geneclius (? – 390×393)

- Aurelius (fl. 393–426)

- Primianus (c. 391), Donatist bishop

- Maximianus (c. 392), Donatist bishop

- Capreolus (fl. 431–435)

- Quodvultdeus (c. 437 – c. 454)

- Deogratias (454–457/8)

- sede vacante

- Eugenius (481–505)

- sede vacante

- Boniface (523 – c. 535)

- Reparatus (535–552)

- Primosus or Primasius (552 – c. 565)

- Publianus (fl. c. 565–581)

- Dominicus (fl. 592–601)

- Licinianus (d. 602)

- Fortunius

- Victor (646–?)[29]

- ...

- Stephen

- ...

- James (974×983)

- ...

- Thomas (1054)

- Cyriacus (1076)

Titular see

Today, the Archdiocese of Carthage remains as a titular see of the Catholic Church, albeit vacant. The equivalent contemporary entity for the historical geography in continuous operation would be the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tunis, established in 1884.

See also

- North Africa during Antiquity

- Early African church

- Primate of Africa

- Councils of Carthage

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tunis

References

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (2002). "Carthage". Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Facts on File library of world history (Rev. ed.). New York: Facts On File. pp. 97–98. ISBN 9781438110271.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. "Africa". Catholic Encyclopedia. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1913).

- ^ François Decret, Early Christianity in North Africa (James Clarke & Co, 25 Dec. 2014) p86.

- ^ Leo the Great, Letters89.

- ^ Plummer, Alfred (1887). The Church of the Early Fathers: External History. Longmans, Green and Company. pp. 109.

church of africa carthage.

- ^ a b Benham, William (1887). The Dictionary of Religion. Cassell. pp. 1013.

- ^ a b Ekonomou 2007, p. 22.

- ^ a b Gonzáles, Justo L. (2010). "The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation". The Story of Christianity. Vol. 1. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 91–93.

- ^ a b c d e f

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Mesnage, Joseph; Toulotte, Anatole (1912). L'Afrique chrétienne : évêchés et ruines antiques. Description de l'Afrique du Nord. Musées et collections archéologiques de l'Algérie et de la Tunisie (in French). Vol. 17. Paris: E. Leroux. pp. 1–19. OCLC 609155089.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Mesnage, Joseph; Toulotte, Anatole (1912). L'Afrique chrétienne : évêchés et ruines antiques. Description de l'Afrique du Nord. Musées et collections archéologiques de l'Algérie et de la Tunisie (in French). Vol. 17. Paris: E. Leroux. pp. 1–19. OCLC 609155089.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Cheyne, Thomas K.; Black, J. Sutherland, eds. (1903). "Epaenetus". Encyclopaedia Biblica. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan. col. 1300. OCLC 1084084.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Cheyne, Thomas K.; Black, J. Sutherland, eds. (1903). "Epaenetus". Encyclopaedia Biblica. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan. col. 1300. OCLC 1084084.

- ^ Handl, András; Dupont, Anthony. "Who was Agrippinus? Identifying the First Known Bishop of Carthage". Church History and Religious Culture. 98: 344–366. doi:10.1163/18712428-09803001. S2CID 195430375.

- ^ "Cartagine". Enciclopedia Italiana di scienze, lettere ed arti (in Italian). 1931 – via treccani.it.

- ^ Toulotte, Anatole (1892). "Carthage". Géographie de l'Afrique chrétienne (in French). Vol. 1. Rennes: impr. de Oberthur. pp. 73–100. OCLC 613240276.

- ^ Morcelli, Stefano Antonio (1816). "Africa Christiana: in tres partes tributa". Africa christiana. Vol. 1. Brescia: ex officina Bettoniana. pp. 48–58. OCLC 680468850.

- ^ Gams, Pius Bonifacius (1957) [1873]. "Carthago". Series episcoporum ecclesiae catholicae : quotquot innotuerunt a beato Petro Apostolo (in Latin). Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. p. 463. OCLC 895344169.

Gams "ignored a number of scattered dissertations which would have rectified, on a multitude of points, his uncertain chronology" and Leclercq suggests that "larger information must be sought in extensive documentary works." (Leclercq, Henri (1909). "Pius Bonifacius Gams". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6.) - ^ a b Hassett, Maurice M. (1908). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "First synods at Carthage and Rome on account of Novatianism and the Lapsi (251)". cristoraul.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-20. Retrieved 2014-08-29. Transcribed from

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hefele, Karl J. von, ed. (1894). A history of the Christian councils from the original documents, to the close of the council of Nicaea, A.D. 325. Vol. 1. Translated by William R. Clark (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 93–98. OCLC 680510498.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hefele, Karl J. von, ed. (1894). A history of the Christian councils from the original documents, to the close of the council of Nicaea, A.D. 325. Vol. 1. Translated by William R. Clark (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 93–98. OCLC 680510498.

- ^ (Contractus), Hermannus (2008-08-20). "Patrologia Latina, vol. 143, coll. 727–731". Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ Primus archiepiscopus et totius Africae maximus metropolitanus est Carthaginiensis episcopus

- ^ Mas-Latrie, Louis de (1883). "L'episcopus Gummitanus et la primauté de l'évêque de Carthage". Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. 44 (44): 77. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ nec pro aliquo episcopo in tota Africa potest perdere privilegium semel susceptum a sancta Romana et apostolica sede: sed obtinebit illud usque in finem saeculi, et donec in ea invocabitur nomen Domini nostri Iesu Christi, sive deserta iaceat Carthago, sive gloriosa resurgat aliquando

- ^ Sollier, Joseph F. (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Bouchier, E.S. (1913). Life and Letters in Roman Africa. Oxford: Blackwells. p. 117. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ François Decret, Early Christianity in North Africa (James Clarke & Co, 2011) p200.

- ^ Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten By Heinz Halm, page 99

- ^ Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition By David E. Wilhite, page 332-334

- ^ "citing Mohamed Talbi, "Le Christianisme maghrébin", in M. Gervers & R. Bikhazi, Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands; Toronto, 1990; pp. 344–345".

- ^ Olga Cecilia Méndez González (April 2013). Thirteenth Century England XIV: Proceedings of the Aberystwyth and Lampeter Conference, 2011. Orbis Books. ISBN 9781843838098., page 103-104

- ^ Curtin, D. P. (February 2020). Letter to Pope Theodore. Dalcassian Publishing Company. ISBN 9781960069719.

Bibliography

- François Decret, Le christianisme en Afrique du Nord ancienne, Seuil, Paris, 1996 (ISBN 2020227746)

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. (2007). Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern influences on Rome and the papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752. Lexington Books.

- Paul Monceaux, Histoire littéraire de l'Afrique chrétienne depuis les origines jusqu'à l'invasion arabe (7 volumes : Tertullien et les origines – saint Cyprien et son temps – le IV, d'Arnobe à Victorin – le Donatisme – saint Optat et les premiers écrivains donatistes – la littérature donatiste au temps de saint Augustin – saint Augustin et le donatisme), Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1920.

External links

- Leclercq, Henri (1907). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1.

- (in French) Les racines africaines du christianisme latin par Henri Teissier, Archevêque d'Alger