Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

| Shaba I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Shaba Invasions and the Cold War | |||||||

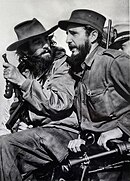

Zairian troops with a beret-wearing Moroccan military advisor | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Zaire: 3,000-4,000[11] Morocco: 1,300[1]–1,500 paratroopers Egypt: 50 Pilots and Technicians[12] France: 20-65 soldiers[1] Belgium: 80 soldiers[1] | 1,600–3,000 FNLC fighters | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Morocco: 8 killed[7] | ~100+ killed | ||||||

Shaba I was a conflict in Zaire's Shaba (Katanga) Province lasting from 8 March to 26 May 1977. The conflict began when the Front for the National Liberation of the Congo (FNLC), a group of about 2,000 Katangan Congolese soldiers who were veterans of the Congo Crisis, the Angolan War of Independence, and the Angolan Civil War, crossed the border into Shaba from Angola. The FNLC made quick progress through the region because of the sympathizing locals and the disorganization of the Zairian military (Forces Armées Zaïroises, or FAZ). Travelling east from Zaire's border with Angola, the rebels reached Mutshatsha, a small town near the key mining town of Kolwezi.

Zairian President Mobutu Sese Seko accused Angola, East Germany,[6] Cuba and the Soviet Union of sponsoring the rebels. Motivated by anticommunism and by economic interests, both the Western Bloc and China sent assistance to support the Mobutu regime. The most significant intervention, orchestrated by the Safari Club, featured a French airlift of Moroccan troops into the war zone. The intervention turned the tide of the conflict.[13] US President Jimmy Carter approved the shipment of supplies to Zaire but refused to send weapons or troops and maintained that there was no evidence of Cuban involvement.

The FAZ terrorized the population of the province during and after the war. Bombing and other acts of violence led 50,000 to 70,000 refugees to flee into Angola and Zambia. Journalists were prevented from entering the province, and several were arrested. However, Mobutu won a public relations victory and ensured continuing economic assistance from governments, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and a group of private lenders led by Citibank.

The FAZ and outside powers clashed again with insurgents in a 1978 conflict, Shaba II.

Background

Zaire

A former Belgian colony, the Congo gained independence during the Year of Africa. The State of Katanga, led by Moise Tshombe, soon announced secession, supported by Belgian business interests, the Belgian military and indirectly by France.[14]

The country was soon plunged into crisis after the assassination of its Pan-Africanist leader, Patrice Lumumba. After six years of war, power was seized by Joseph Mobutu, with help from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and support from the Western Bloc. Mobutu changed the name of Katanga Province to Shaba Province, after the Swahili word for copper.

Mobutu's Zaire maintained good relations with Western powers. Belgium had the largest investments in the country (worth $750 million to $1 billion), followed by the United States ($200 million) and France ($20 million). Franco-Zairian relations were improving, and the Zaire government had recently been snubbing Belgium for France by awarding the country a $500 million telecommunications contract in 1975. The contract, negotiated by French President Giscard d'Estaing, went to Thomson-CSFInternational with finances from the Banque Française du Commerce Extérieur, both institutions headed by members of Giscard d'Estaing's family. When Mobutu asked for international assistance, it was France that organised the military response.[14][15][16]

Zaire received more military aid from the United States than any other sub-Saharan nation,[17] the $30 million of annual assistance representing half of all military aid to the area.[18]

Zaire was the world's primary exporter of cobalt and sourced 60% of the global supply.[19] The country also exported 7% of world copper and 33% of industrial diamonds. Many of the mines for these resources were in Shaba,[18] and the copper mines in the area provided 65–75% of the country's overall wealth from imports.[20]

FNLC

The FNLC had mostly Lunda people, the ethnicity of many people in Katanga which was renamed Shaba in 1972. In 1976, it began to recruit youth in Katanga to join its fighting force.[21]

Formation

Included in the invading force was a small remnant of the Katangan gendarmes that had supported the secession of Katanga from 1960.[22] When Joseph Kasa-Vubu recalled the Katanganese leader Moise Tshombe from exile in 1964, elements of the force had been incorporated into the Armee Nationale Congolaise (ANC) to help fight the insurrections simmering throughout the country.[22] After Tshombe disappeared from the political scene, the Katangan contingent mutinied in 1966 and again in 1967.[22] When the uprisings failed, most of the contingent left for Angola under Nathaniel Mbumba's leadership.[22] During the late 1960s, the former gendarmes began to congregate in Angola along Zaire's southern border, and in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, they fought for the Portuguese against Angolan nationalist movements.[22]

After the Portuguese left in 1975, the Katangan gendarmes fought for the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in the Angolan Civil War. The MPLA won control of the country and provided the gendarmes with relative autonomy in their area on the border with Zaire. The group, about 4000 people total of whom 2000 were deemed able to fight, formed the Front for the National Liberation of the Congo (FNLC) and styled itself as left-wing.[23]

Cuban involvement

The FNLC had earlier asked Cuba directly for assistance but it declined since it was already seeking to withdraw from Angola and was not convinced of the FNLC's sincerity.[24] The extent of the MPLA's support for the invasion is unclear; it did not seem provide much direct assistance but also did not act to prevent the attack.[25] Cuba did not support the FNLC in the invasion.[26]

Invasion

The invaders launched a three-pronged attack on 8 March 1977, crossing the Angola–Zaire border on bicycles.[21][22] No casualties were reported in the first week after their arrival.[27]

Zaire's response

Mobutu condemned the invasion and said on 10 March that Kissenge, Dilolo and Kapanga had been "bombed" by "mercenaries".[28] He accused the Cuban government of involvement and requested assistance from Western powers.[29] The US embassy confirmed that the towns had been captured and announced that eight American missionaries in Kapanga were under house arrest.[30]

The actions of Zaire's armed forces, the FAZ, were largely ineffective.[21] The first unit to make contact, the 11th Brigade of the Kaymanyola Division, was newly trained, and it fell apart soon after it had met the FNLC force.[31] However, the popular uprising hoped for by the FNLC also did not materialize. Although most towns preferred the FNLC forces to the government army,[32] people were generally afraid of violence and stayed home.[33]

International response

United States

On 15 March, the United States sent 35 tons of communications equipment and medical supplies, and other materials, worth a total of $2 million, by using chartered DC-8s.[17][34] President Jimmy Carter, in his first year of office, was less enthusiastic about Mobutu than his predecessors had been and decided against sending weapons or troops.[35][36] He also stated that there was no evidence to substantiate Cuban involvement and maintained that position throughout the conflict.[36] Officials of NATO agreed.[37] The State Department accused the Angolan government of providing the rebels with "logistic support"[38] but maintained that there was "no hard evidence" of Cuban support.[39]

The U.S. House Committee on International Relations questioned the importance of aid and moved to halve Zaire's arms credits from $30 million to $15 million.[40] Americans were evacuated from the area.[27] Secretary of State Cyrus Vance sought to justify the aid based on the importance of copper and cobalt mining.[41][42]

Announcements seeking to hire American mercenaries to fight in Zaire appeared in California. A man, David Bufkin, was identified as doing the recruiting. The announcements were later traced to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)[43][44]

Other countries

Belgium sent weapons to the Zaire government[45] but declined Mobutu's request for military assistance.[46] China sent 30 tons of weapons.[45] France sent weapons and ammunition.[47][48] Sudanese President Gaafar Nimiery announced in April 1977 that Sudan would provide aid to Zaire.[49]

The US asked for Nigeria's help with diplomatic mediation between Zaire and Angola. Nigeria agreed but urged outside powers not to provide arms.[4][5]

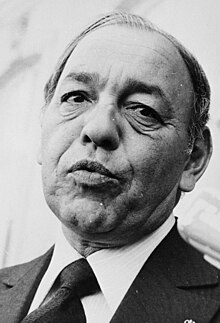

Cuban President Fidel Castro denied that Cuba was involved in the conflict and called Mobutu "desperate" and the accusation being "a pretext to get military assistance from imperialism so he can continue to oppress the people of Zaire".[50]

Banks

Zaire had already been overdue on its loan payments, and the conflict increased the uncertainty of international banks of its ability to repay.[51] A group of 98 banks, led by Citibank, had agreed in November 1976 to offer Zaire a $250 million loan if the country promised to implement economic austerity. The banks hoped that the additional loan would help Zaire develop its economy and pay back the $400 million that it already owned.[52] The banks feared that the war would now bankrupt Zaire's government.[53][54] Citibank announced on behalf of the group that the loan would be suspended until Zaire could resolve its internal problems, which would have jeopardised repayment.[55]

Invasion continues

The FNLC progressed into Katanga. In a battle in Kasaji on 18 March, the FAZ killed 15 of the FNLC soldiers and lost 4 of its own.[56] On 25 March, the FAZ abandoned Mutshatsha, and the FNLC entered it. The town had railway access and was 130 km from the Kolwezi, home to the Musonoi Mine, a major source of copper for Gécamines. The capture of Mutshatsha led observers to perceive a serious threat from the invading force.[57][58][59] (Despite its economic importance, Kolwezi was not particularly well-defended. A Belgian manager suggested: "No one would dare to touch us. We are essential to whoever governs this area, so we are not worried.")[60] Americans in Kolwezi, mostly workers for Morrison-Knudsen, were evacuated.[61]

The perception of the rebels' power increased as reports suggested they were beginning to provide social assistance to local people in the Shaba province.[62] The FNLC began to establish a regional administration and to distribute identity cards for a nation called "The Democratic Republic of the Congo".[9] According to later reports from missionaries in the area, the rebels, whose primary agenda was freedom from Mobutu, not ethnic or tribal warfare, were welcomed by locals in Katanga.[63]

The government held a poorly-attended rally in a Kinshasa stadium. Soldiers prevented the already-small crowd from leaving afterward, and the rally ended when the crowd refused to applaud.[64][65]

Zaire launched bombing raids in the area, which it said were targeting the invaders. The Zairian Air Force used Mirage jets from France to bomb Kisengi, which it called the headquarters for the rebel uprising.[66] Along with other residents, 28 missionaries from Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, France, Belgium, Italy and Spain fled from the bombing raids, eventually taking refuge in Angola.[63][67]

Angola reported that Zaire had bombed its towns of Shilumbo and Camafuafa.[68]

The Zairian military claimed to have killed Russian, Portuguese and Cuban soldiers participating in the invasion.[69][70] Zaire cut diplomatic ties with Cuba and then the Soviet Union.[71]

On a diplomatic visit to Washington, DC, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat emphasised that claim to Carter, who maintained throughout the conflict that there was no evidence of outside involvement.[69][72] King Hassan II of Morocco said he had "absolutely certain" proof that Cuban soldiers were fighting in Shaba.[73]

Andrew Young, the US ambassador to the United Nations, urged calm by saying "Americans shouldn't get paranoid about communism" in Africa.[74] Mobutu reproached the United States in a Newsweek interview and said that he was "bitterly disappointed by America's attitude"[75] and "If you have decided to surrender piecemeal to the Soviet-Cuban grand design in Africa, I think you owe it to us and to your friends to have the frankness to admit it."[27] Former National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger also blamed the Soviet Union: "Whatever the details of the current invasion of Zaire, it is clear that the attack took place across a sovereign border from a country in which the government was installed by Soviet arms and the military personnel of a Soviet client state. It could not have taken place—and it could not continue—without the material support or acquiescence of the Soviet Union—whether or not Cuban troops are present."[76] China concurred, provoking unpleasantness with Soviet ambassadors in Beijing[77] and later calling the FNLC invasion "a new offensive drive in the Soviet Union's political and military aggression in Africa".[78]

Meanwhile, Carter was also criticised for the support that he gave to Zaire, in contrast with his support for human rights. Senator Dick Clark, a member of the Foreign Relations Committee, publicly opposed the US involvement and wrote in an op-ed:

In my judgment, U.S. involvement in Zaire defies justification. It is true that the U.S. has not utilized the full measure of resources available for Zaire, nor responded to Mobutu's requests for arms and ammunition. This restraint by the Administration is commendable, but if Mobutu qualifies for neither arms nor ammunition, then he should not qualify for any form of military assistance, lest the United States be drawn into the hapless conflict in Zaire, inch by inch.[79]

John Stockwell, who grew up in Katanga, joined the CIA and eventually became the head of its Angola Task Force, publicly resigned his position, blaming the conflict on unsuccessful CIA interventions. In an open letter to CIA Director Stansfield Turner published in the Washington Post, Stockwell argued that American intervention in Zaire and Angola was triggering a backlash in the Third World:[16][80][81] "In death [Lumumba] became an eternal martyr and by installing Mobutu in the Zairian presidency we committed ourselves to the 'other side', the losing side in central and southern Africa. We cast ourselves as the dull-witted Goliath, in a world of eager young Davids."[82] Stockwell expanded on his claims of CIA abuses in a 1978 book titled In Search of Enemies.

Carter acknowledged problems with human rights in Zaire but said that "our friendship and aid historically for Zaire has not been predicated on their perfection in dealing with human rights."[72][83]

Confusion and censorship

Journalists reported confusion and difficulty with finding credible information.[84][85] American news sources reported that Kolwezi had been captured[86][87] but retracted that claim.[84][88] Reportedly, even the CIA, which operated a station in Kinshasa, did not collect intelligence directly in the Shaba region.[85]

Reliable information became even more difficult to obtain after the FAZ abandoned Mutshatsha, and Mobutu declared the right to censor all news reports.[89] The journalist Michael Goldsmith was expelled from Zaire on 4 April after reporting that the aforementioned rally in Kinshasa had been lackluster.[90] More journalists were arrested, and films taken in Kinshasa were seized by the Zaire government.[62]

The press of Zaire ignored the Shaba conflict entirely.[62]

Meanwhile, the FNLC did not seem to have press contacts.[85]

Zairian military

Mobutu relieved Colonel Salamaya, whom he had placed in charge of defending Shaba six days earlier, and soon relieved Salamaya's replacement.[91] Mobutu blamed the success of the rebel attack on high-ranking traitors in the Forces Armées Zaïroises, the Zairian military.[92]

FAZ casualties remained low, with many FAZ forces apparently unwilling to fight.[93] Many of the Zairian soldiers had not recently been paid,[84] and numerous reported desertions and defections occurred.[59] One missionary reported FAZ soldiers intentionally wounding themselves to avoid battle.[63]

A Belgian engineer in Kolwezi, discussing the apparent unpreparedness of its FAZ forces, told a reporter: "Ah, it's an African war. What can you expect? If the Katangans get really close, many of these soldiers will run anyway. All it takes is a loud bang, and off they go."[60]

Safari Club intervention

On 7 April, plans were announced to support the government of Zaire with Moroccan troops.[94] The operation was co-ordinated by a covert multinational organization, the Safari Club, an anticommunist alliance including France, Morocco, Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia.[95][96]

On 9 April, Moroccan troops were airlifted into Kolwezi on eleven French Transall C-160s from the network of French bases remaining on the African continent.[45][97][98] Egypt also provided 50 pilots and technicians, who operated Mirage fighter jets from the Zairian Air Force.[12] France also assisted the FAZ with additional Mirage planes, Panhard Véhicule Blindé Légers and Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma helicopters.[98]

After Western military support had arrived in Kolwezi, Zambia said that Zaire had bombed the village of Shingamjunji Mangango and the Kaleni Hill mission hospital.[99][100] Angola also reported a naval attack.[101]

Diplomacy and media

A French liaison was deployed to co-ordinate with the Zairian forces.[91] The French operation (codename "Verveine"),[97] was commanded by Colonel Yves Gras, the head of the French Military Mission in Zaire.[3] Morocco provided 1,300 to 1,500 combat troops, Egypt contributed pilots and technical support and Saudi Arabia backed the operation financially.[3]

Moroccan troops increased the perception that the operation was internal to Africa,[98] with Zaire originally announcing that Morocco and "another African country" were coming to its assistance.[102] The American government also described the intervention as intra-African, with Carter announcing, "We are not taking a position on such action by one African state at this point in response to requests for aid from another African state. Our position on outside intervention is well known. We are against such intervention. The affairs of Africa should be settled by Africans."[103]

Some African states, particularly former colonies of France, supported Zaire diplomatically. Idi Amin and a symbolic "suicide striking force" of the Ugandan military visited Kolwezi in late April and then flew back to Uganda.[69][104] Uganda was the third African country to discuss the possibility of sending soldiers to help Zaire.[105]

The French announcement that it would provide the airlift, made on 10 April "came as a surprise to all observers."[106] President Giscard d'Estaing emphasised France's independence in conducting the operation and specified that the US had not been consulted.[107]

The US announced an additional $13 million of aid, including a C-130 transport plane, communications equipment, fuel and spare parts.[108] Andrew Young, who advised restraint throughout the conflict, said that the US was trying to "align ourselves with the... concept of territorial integrity in Zaire, and of self-determination by the people of Zaire, but not get ourselves in the military conflict."[109] Carter continued to state that there was no evidence of Cuban involvement. He acknowledged that Zaire was not a "defender of human rights" and said that "our military aid for Zaire has been very modest".[72]

The South African Bureau of State Security was also in contact with Zaire and provided fuel and money.[110]

West Germany sent $2 million worth of medicine and food.[111]

Initial reactions

The FNLC began to make contact with the press and issued several announcements. A representative of the Katanganese rebels, speaking in Paris, criticised the intervention as economically self-serving: "the stake of French multinationals such as Alsthom and Thomson, and concessions for prospecting the mineral riches" had led France to support "a corrupt regime".[106] Jean Tshombé, son of former Katanganese secessionist leader Moise Tshombé, also criticised the intervention and reaffirmed that Angola, Cuba and the Soviet Union were not involved.[112] The FNLC then announced specific military successes and said that it had defeated Zairian military forces 15 miles from Kolwezi and seized vehicles and weapons.[111][113] It also claimed to have killed two French soldiers, a claim quickly denied as impossible by France, which said that no French soldiers were present.[114] The group wrote a letter to the International Press Service:[115]

In contrast with published statements of with published statements by President Giscard D'Estaing, French troops are directly involved in the fighting currently taking place in the Shaba province of Zaire. This Friday, 15 April, at 2 p.m., the fighting spread on the outskirts of Kolwezi. A French military man died amid these engagements.

The FLNC strongly protests this French military intervention in Congo's domestic affairs and declined any responsibility for the consequences it may bring upon the French Government.

The FLNC calls on the French people, to whom it expresses its trust and friendly feelings, to demand the immediate termination of the aggression deliberately carried out against the Congolese people.

Angola declared the invaders "responsible for the grave consequences that may result from their intervention in the conflict" and warned that "if the objective is to attack Angola, the Popular Republic of Angola warns Africa and the world that it will not tolerate any foreign intervention".[116] The Soviet Union condemned the Western Bloc and China for interfering in a "strictly internal conflict which need not concern anyone outside [Zaire]."[117]

The alleged Zairian bombings of Angola and Zambia also became an issue, with Mobutu accusing the Soviet Union of bombing the countries as false flag attacks.[113]

French intervention met with left-wing criticism, domestically and internationally.[118][119] President Giscard d'Estaing responded that the action was protecting the sovereignty of a friendly state. Foreign Minister Louis de Guiringaud said that it was necessary to check Soviet influence.[120] The French government denied claims that "military advisors" had participated in the fighting.[121]

Belgium denied a claim made by Mobutu and quoted in Newsweek that it was involved in the conflict and said that the only assistance that it had delivered had been preplanned.[122]

Execution

The war itself seemed to be in a stalemate, with foreign troops and the FAZ now massed in Kolwezi but little fighting taking place.[123] On 14 April, Moroccan General Ahmed Dlimi arrived in Kolwezi, and a combined Zairian and Moroccan force counterattacked.[9][10] 30 FAZ casualties were reported after a fortnight of quiet.[78] It was joined by a unit of Pygmy archers.[124]

The government and supporting forces reported capturing rebel supplies, including counterfeit money and Portuguese- and Soviet-manufactured weapons. Two captured Kantangan soldiers said that there were 1,600 soldiers in Shaba, their leader was Nathaniel Mbumba and they were not being assisted by Cuba.[125] One said, "First we were trained by the Portuguese and after that by the Cubans"—but "there are no Cubans now".[126]

The government displayed the two captives in another stadium rally in which Mobutu again condemned Soviet and Cuban involvement and ordered $60,000 worth of Coca-Cola to go along with rations for FAZ soldiers.[126][127][128] Mobutu flew with diplomats and journalists to Kolwezi, where he was met by dancing girls and announced a "total rout" of the insurgents.[129]

The pro-government alliance recaptured Mutshatsha on 25 April.[83][130] The village was nearly deserted when it was captured, but observers assigned symbolic importance to its recapture.[131][132] Mobutu held a press conference and parade in Mutshatsha, telling 47 international journalists that he would continue to battle Soviet influence in Africa. That day, the International Monetary Fund said that it would lend Zaire $85 million. There was speculation that this may have been done to deter a group of private banks from canceling the existing loan of $250 million.[83][133] At the request of France and the United States, the World Bank announced an upcoming convention to solicit additional loans for Zaire.[53]

David Bufkin's mercenaries were reported ready to fly to Zaire to join the anti-FNLC coalition.[134] The CIA denied a request from the Department of Justice to provide information about its involvement.[135] Bufkin and the CIA denied the claim.[119][136] The operation was aborted after the Safari Club intervention proved rapidly successful.[137]

Conclusion

More confusion

The situation was confusing, chaotic and difficult to assess. Observers were unsure of whether the war had ended with a victory for the Zaire government or had devolved into a guerrilla war.[138] Journalists continued to face restrictions and intimidation.[139] Seven European journalists (including Colin Smith) had been arrested in April and accused of illegally entering Shaba.[140][141] A spokesperson for the Zaire military stated: "In the normal way these people should have been treated as mercenaries and shot immediately. It is a miracle they are still alive."[142] The journalists were removed from Zaire after they had imprisoned for two weeks.[143]

According to a contemporary news report:

Newsmen in Kinshasa, 1,500 miles from the Kolwei battlegrounds, repeatedly refused permission to visit Shaba province, finally received permission to visit the region and after a 10-day visit reported that they had not heard a single shot fired. In Kolwezi's hospital only two slightly wounded Zairian soldiers had been seen.

If there was a war going on nobody seemed to know where the front was. Nevertheless, the general staff of the Zaire army was claiming to have begun a general offensive against the enemy and claimed to have surrounded the town of Mutshatsha.

Mobutu's patchwork army of reluctant unemployed urban youths, displaced farmers' sons, the restless Moroccans and the Pygmies face an estimated 100 battle groups, each consisting of 30 well trained and well armed men operating deep inside friendly trail areas.[128]

The sympathies of the local people were also in question, with observers unsure of how many residents of Shaba supported the rebels. The image of the FAZ–Moroccan forces deteriorated when three Moroccan troops stabbed a Kolwezi woman to death and beat her babies after she denied them sex.[10] (It was later determined that the soldiers raped the woman and killed her babies with bayonets and would be executed after military tribunal in Shaba.)[144][145] Local people were threatened, imprisoned and killed by the Zairian military in an effort to prevent them from joining the rebels.[146] The European, Australian and Canadian missionaries who surfaced after fleeing to Angola said that locals supported the rebels, none of whom being Cuban or Angolan, because they opposed Mobutu.[63][67]

Final military actions

The Moroccan and Zairian troops moved on, bolstered by additional noncombat forces from France, Egypt and Belgium.[147] The coalition retook the area with occasional fighting. It suffered some casualties from an FNLC ambush in Kasaji.[148]

American workers returned to Kolwezi soon after the capture of Mutshatsha.[149]

On 21 May, the government announced that Dilolo had been captured.[150] It said that 100 rebels were killed in simultaneous attacks at Kapanga and Sandoa.[151] The war was declared over.[152][153] Kapanga was declared captured on 26 May 1977.[154]

Aftermath

As the FAZ, with France, Morocco, Egypt and Belgium, drove the rebels out of Zaire, the Ethio-Somali Ogaden War created another international crisis involving the United States, the Safari Club, Cuba and the Soviet Union.[155][156]

In July 1977, Mobutu disclosed that Saudi Arabia had provided an undisclosed form of aid during the conflict.[157]

FNLC

The FNLC withdrew to Angola and possibly to Zambia and began to regroup for another attack.[22] The group gained many new recruits and left behind contacts within Shaba Province.[33]

Katanganese

Military terror against Lunda people in the region, who shared the ethnicity of the gendarmes, led 50,000–70,000 people to flee Zaire for Angola.[158][22] In February 1978, the FAZ entered the town of Idiofa, killed between 500 and 3,000 people, hanged fourteen "ringleaders" and burnt villages.[128][159]

Zaire

The military reported 219 casualties during the course of the war.[160]

The poor performance of Zaire's military during Shaba I gave evidence of chronic weaknesses.[22] One problem was that some of the Zairian soldiers in the area had not received pay for extended periods.[22] Senior officers often kept the money intended for the soldiers, typifying a generally disreputable and inept senior leadership in the FAZ.[22] As a result, many soldiers simply deserted, rather than fight.[22] Others stayed with their units but were ineffective.[22]

During the months after the Shaba invasion, Mobutu sought solutions to the military problems that had contributed to the army's dismal performance.[22] Foreign Minister Jean Nguza Karl-i-Bond, the country's second-ranking official, an expert on international law and a member of the Lunda ethnic group, was accused of treason[161][162] sentenced to death,[163][164] reprieved by Mobutu and sentenced to life in prison.[165] (He was later pardoned and reappointed Foreign Minister.) A former Zairian military officer and a former governor were condemned to death in August 1977, also charged with aiding the FNLC.[160] Subsequent trials in 1978 implicated 68 military officers, dispensing 19 death penalties and numerous imprisonments.[33]

Mobutu also reorganised the FAZ and began training for the Kamanyola division in Kolwezi. The training was assisted by French, Belgian and American military advisors.[166]

In the reorganisation, Mobutu dismissed a Belgian officer, Van Melle, from his own intelligence services. Van Melle was a key contact for European and American intelligence agencies, and his dismissal made reliable information even harder for them to find.[167]

Mobutu merged the military general staff with his own presidential staff and appointed himself chief of staff again, in addition to the positions of minister of defence and supreme commander that he already held.[22] He redeployed his forces throughout the country, instead of keeping them close to Kinshasa, as had previously been the case.[22] The Kamanyola division, then considered the army's best unit and referred to as the president's own, was assigned permanently to Shaba.[22] In addition, the army's strength was reduced by 25%, presumably to eliminate disloyal and ineffective elements.[22] Zaire's allies provided a large influx of military equipment, and Belgian, French and American advisers assisted in rebuilding and retraining the force.[22]

Shaba I was a major public relations victory for Mobutu by securing his regime and winning continued military and economic assistance from the Western Bloc.[139][168][169] The group of private lenders, led by Citibank, was close to delivering the $250 million loan in early 1978.[170]

The Shaba II conflict began in May 1978.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Berman, Eric G.; Sams, Katie E. (2000). Peacekeeping In Africa : Capabilities And Culpabilities. Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. ISBN 978-92-9045-133-4. Berman and Sams cite the lower number.

- ^ a b A Little Help from His Friends Time, 04/25/1977, Vol. 109 Issue 17, p.57

- ^ a b c Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 25.

- ^ a b "Nigeria to Move, At U.S. Request, In Zaire Dispute", Washington Post, 23 March 1977, p. A1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Nigeria Appeals on Arms", New York Times, 24 March 1977, p. A7; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Zaire Says East Germany Supplies Arms to Rebels - New York Times, May 1, 1977. Retrieved on April 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Le Sahara occidental, enjeu maghrébin,page 304

- ^ Driss Bennani. "Exclusif. Portrait-enquête. Laânigri. Un destin marocain (Son ascension, sa chute…)". Telquel. No. 239. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ a b c "Moroccan Troops Make Their First Move in Zaire", Los Angeles Times, 17 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Robin Wright, "Moroccan Army Chief Visits Area of Fighting in Zaire", Washington Post, 15 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Katangan Gendarmes Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Leigh Ingram-Seal

- ^ a b Ogunbadejo, "Conflict in Africa" (1979), p. 227.

- ^ Chris Cook and John Stevenson. The Routledge Companion to World History Since 1914, 2005. Pages 321-322.

- ^ a b "France Is Again Strengthening Ties With Zaire", New York Times, 17 April 1977, p. E1; accessed via ProQuest. "Although France did not officially support the secessionists, their leader, Moise Tshombe, employed French advisers and mercenaries and received support from the neighboring Government of Congo, a former French colony. Economic interests: After the Kantanganese rebellion ended in 1963, France expended considerable aid and effort to improve relations with Zaire. French companies now have important mining interests in the country, producer of copper, cobalt and industrial diamonds."

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 27–28.

- ^ a b B. K. Josh, "Zaire Again on the Rack: Sordid Franco-U. S. role", Times of India, 22 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "U.S. Flies Communication, Medical Supplies to Zaire: Responds to Appeal for Aid in Invasion", Los Angeles Times (AP), 15 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Getting Involved: The U.S. Aid for Zaire Was Small But Significant", New York Times, 20 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "A Cobalt Undercurrent in Zaire", New York Times, 20 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Gerald Bender, "Zaire: Is There Any Rationale for U.S. Intervention?", New York Times, 27 March 1977, p. G2; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Glickson, Roger C.; Sinai, Joshua (1994). "Shaba I". In Meditz, Sandra W.; Merrill, Tim (eds.). Zaire: a country study (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 292–294. ISBN 0-8444-0795-X. OCLC 30666705.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), pp. 71–72.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), pp. 73–74, 93–94.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), p. 99–100.

- ^ Ogunbadejo, "Conflict in Africa" (1979), p. 225. "All these points show that Angola was never deeply involved in the invasion. Not even the American Central Intelligence Agency was able to prove any serious involvement, and it is unlikely that, given President Neto's numerous internal problems (political and economic), his government or even his Cuban allies would have dissipated their forces in an attack on Shaba."

- ^ a b c "Zaire preparing major push to confront Shaba guerrillas", Baltimore Sun (AP), 14 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Reports Invasion of South by Mercenaries", Los Angeles Times, 10 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), p. 75.

- ^ "Angolan troops hit Zaire, take 3 towns", Chicago Tribune (Tribune Wire Services), 11 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Robin Wright, "Zaire Peasants, Friendly to Invaders, Spurn Government Troops", Washington Post, 24 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 28.

- ^ Norman Kempster and Oswald Johnson, "U.S. Flies 35 Tons of Supplies to Zaire Defenders", Los Angeles Times, 16 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), pp. 75.

- ^ John Palmer, "NATO doubts on Cubans' role", 15 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Oswald Johnston, "State Dept. says Angola helps Zaire attackers", Boston Globe, 19 March 1977, p. 1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Nelson Goodsell, "Pushing new African countries toward Communist world?", Christian Science Monitor, 21 March 1977.

- ^ Ogunbadejo, "Conflict in Africa" (1979), p. 226.

- ^ Bernard Gwertzman, "Vance Says Invaders in Zaire Threaten Vital Copper Mining: Calls Situation 'Dangerous': He Tells House Panel That Conflict Endangers the Commodity That Sustain's Nation's Economy", New York Times, 17 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Jane Rosen, "Concern in US on Zaire", The Guardian, 17 March 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Ernest Volkman, "CIA backs mercenary recruiting", Boston Globe, 17 April 1977, p. 49; accessed via ProQuest. "Officially, the sources say, both Bufkin and the British mercenaries are recruiting on behalf of Mobutu, who is providing the money for the operation. However, the CIA is actually bankrolling the operation, the sources say."

- ^ CIA Held Having Mercenaries Role", Hartford Courant, 17 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c "Giscard sends 11 planes to aid Zaire fight in Shaba", Baltimore Sun (AP), 11 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 24.

- ^ Robin Wright, "France to Aid Zaire; Fighting Continues", Washington Post, 19 March 1977, p. A12; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire bares troop, arms aid by Morocco, China", Chicago Tribune, 8 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/1977/04/12/archives/sudan-promises-to-send-help.html

- ^ "Castro Denies Any Cuban Role in Invasion of Zaire: Says President Is Weak, Seeks Pretext for Foreign Assistance", Los Angeles Times, 21 March 1977, p. B2; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Daniel Southerland, "Zaire fighting hands Carter a test in Africa: Hostile borders, Loan payments overdue", Christian Science Monitor, 17 March 1977, p. 7; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Ann Crittenden, "Bank Group Plans New Loan to Zaire: Banking Syndicate Is Planning New Loan to Zaire", New York Times, 18 November 1977, p., 86; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Don Oberdorfer and Lee Lescaze, "Zaire Nearly Broke: U.S. Aids Bankers in Bailout for Zaire", Washington Post, 24 April 1977, p. 1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Mark Frankland, "Why the banks are worrying about war", The Observer, 15 May 1977, p. 6; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Ogunbadejo, "Conflict in Africa" (1979), pp. 226, 233. "Citibank rightly felt that a prolonged, or indecisive, end to the conflict could be a continuing drain on Zaire's slender resources. Such a development would affect the country's financial and credit worthiness and, worse, its ability to stay current with repayments on existing commercial debts, much less the new loan."

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 18.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), pp. 76.

- ^ David Lamb, "Zairians Reportedly Give Up Front Base: Move Would Bring Invaders Closer to Heart of Rich Copper Mining District", Los Angeles Times, 28 March 1977, p. B12; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Michael T. Kaufman, "Zairian Troops Said to Abandon Key Headquarters Town in Shaba", New York Times, 28 March 1977, p. 15; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Robin Wright, "Zaire's defenders dozing in tropical sun", Boston Globe, 27 March 1977, p. 22; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Americans flee rebels in Zaire", Chicago Tribune (AP), 30 March 1977, p. B8; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Robin Wright, "Katanga Rebels Tighten Grip in Zaire", The Washington Post, 7 April 1977, p. A16; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d Jane Bergerol, "Civilians 'flee Zaire bombing'", The Guardian, 30 April 1977, p. 1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Zaire's 'most gigantic demonstration' is half-filled stadium and few cheers", Boston Globe (AP), 4 April 1977, p. 2; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Michael T. Kaufman, "ZAIRE SAYS ITS JETS BOMB REBEL POSITION: Mirage Planes Are Reported Used to Attack City Identified as the Headquarters of Invaders", New York Times, 24 March 1977, p. A7; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Zaire Refugees Saw No Cubans, Angolans", Hartford Courant, 1 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Warplanes Bomb Invaders: Angola Says 3 of Its Towns Were Attacked", Los Angeles Times, 23 March 1977, p. 1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), p. 77.

- ^ "Killed Portuguese, Russians and Cubans, Zaire Chief of Staff Says", Los Angeles Times, 3 April 1977, p. A22; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Mobutu Announces End Of Soviet Cooperation", Washington Post, 22 April 1977, p. A23; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c "'It will Definitely Not Have an Adverse Impact on Jobs...'", Washington Post, 23 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest[permanent dead link].

- ^ "Morocco King Says There Is Sure Proof Cubans Are in Zaire", Los Angeles Times (AP), 20 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Young Warns of Fears Over Reds", Los Angeles Times, 12 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), p. 78.

- ^ "Kissinger Urges U.S. and Soviet To End Rhetoric: Says Strong Statement on Zaire is Needed", New York Times, 6 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Timely tips on Zaire", Chicago Tribune, 8 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest. "In Peking, Chinese Vice Premier Li Hsien-nien, presiding at a dinner in honor of the visiting president of Mauritania, deliberately accused the Soviet Union of engineering 'the grave incident of a massive invasion of Zaire by mercenaries.' The Soviet ambassador to China promptly strode out of the Great Hall of the People, followed naturally by the representatives of East Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Mongolia, and Cuba."

- ^ a b "Renewed fighting flares in Zaire; rebels wound 30", Chicago Tribune, 16 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Dick Clark, "America Has Already Done Too Much for Zaire's Hapless Government", Los Angeles Times, 1 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman, Political Economy of Human Rights: After the Cataclysm: Postwar Indochina and the Reconstruction of Imperial Ideology, Black Rose Books, 1979; p. 308.

- ^ Jonathan Steele, "CIA is blamed for Zaire invasion", The Guardian, 11 April 1977, p. 4.

- ^ John Stockwell, "Why I Am Leaving The CIA", Washington Post, 10 April 1977.

- ^ a b c Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), p. 79.

- ^ a b c Michael T. Kaufman, "Information on Fighting in Zaire Sometimes Conflicting and Wrong", New York Times, 26 March 1977, p. 7; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c David Lamb, "Data Remains Scant On Katangan Attack In Remote Zaire Area", Washington Post, 30 March 1977, p. A19; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Key Copper-Mining Center in Zaire Reported Taken by Rebel Invaders", New York Times (AP), 18 March 1977, p. A1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Henry L. Trewhitt, "U.S. arms aid to Zaire considered: Congress consulted as rebel troops seize copper center", Baltimore Sun, 18 March 1977, p. A1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Michael T. Kaufman, "Zaire Flying Troops to Battle Area in Bid to Repulse Invaders: Drive to Defend Copper City: Size of Force Moving on Kolwezi, Made Up Mostly of Ex-Militiamen From Katanga, Put at 2,000; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Censorship Imposed In Zaire", Hartford Courant (AP), 1 April 1977, p. 1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Orders Expulsion Of AP Correspondent", Washington Post, 5 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 19.

- ^ "Zaire Leader Blames Traitors", Zaire Leader Blames Traitors, Hartford Courant, 10 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Jim Hoagland, "Zaire army 'avoiding fight'", The Guardian, 26 March 1977, p.3; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Boussaid, Farid (18 March 2020). "Brothers in Arms: Morocco's Military Intervention in Support of Mobutu of Zaire During the 1977 and 1978 Shaba Crises". The International History Review. 43: 185–202. doi:10.1080/07075332.2020.1739113. ISSN 0707-5332.

- ^ Mahmood Mamdani, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terrorism; New York: Pantheon, 2004; ISBN 0-375-42285-4; p. 85. "The club's first success was in the Congo. Faced with a rebellion in mineral-rich Katanga (now Shaba) province in April 1977 and a plea for help from French and Belgian mining interests conveyed through their close ally Mobutu, the club combined French air transport with logistical support from diverse sources to bring Moroccan and Egyptian troops to fight the rebellion."

- ^ Helmy Sharawi, "Israeli Policy in Africa"; in The Arabs and Africa, ed. Khair El-Din El-Din Haseeb, Milton Park: Routledge, 2012; ISBN 9780415623957; p. 305.

- ^ a b Van Nederveen, USAF Airlift into the Heart of Darkness (2004), p. 47.

- ^ a b c Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 26.

- ^ "Zambia Reports Bombing", New York Times, 13 April 1977, p. 9; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Mobutu's planes 'bombed Zambia'", The Guardian (Reuters), 14 April 1977, p. 6; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Merchant ship hit: Fierce new fighting in Angola reported", Chicago Tribune, 14 April 1977, p. 12; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "2 African Nations Sending Troops to Help, Zaire Says", Los Angeles Times, 8 April 1977, p. B1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Graham Hovey, "Washington Seems To Favor Assistance Given Zaire Regime", New York Times, 9 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Michael T. Kaufman, "Amin Arrives in Zaire, Pledges Aid To Mobutu Against Shaba Invaders", New York Times, 23 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Amin Offers to Aid Zaire With Troops, Supplies". Washington Post. 23 April 1977. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b Andreas Freund, "France airlifting Moroccan soldiers to help out in Zaire: Unexpected Announcement Asserts Paris Made Decision to Aid Fight Against 'Outsiders'", New York Times, 11 April 1977, p. 1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Jim Browning, "Giscard assures French: no Vietnam in Zaire: France acted independently, he asserts", Christian Science Monitor, 14 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "U.S. Will Send Nonlethal Aid to Zaire Army", Los Angeles Times, 12 April 1977, p. A1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "U.S. 'In Support Position' On Zaire, Young Says", Washington Post, 15 April 1977, p. A12; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Robin Wright, "S. Africa reportedly will aid Zaire", Boston Globe, 9 April 1977, p. 2; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "W. Germany Sends Zaire Aid as Invaders Claim Big Win", Hartford Courant (AP), 15 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Rebel forces renew fight in Angola", Baltimore Sun, 14 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Nearing Key Town, Zaire Invaders Say", Los Angeles Times, 15 April 1977, p. B7; accessed via saProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire President Hits U.S., Vows Victory", Los Angeles Times, 15 April 1977, p. A2; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "French soldier killed in Zaire", The Guardian, 16 April 1977, p. 5; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Foreign Aid To Zaire Spurs Threat From Marxist Angola As Tense Situation Worsens: Mobutu Repeats Charge of Cuban, Russian Influence", Atlanta Daily World (AP), 12 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Russ Accuse West, China of Interference in Zaire", Los Angeles Times, 13 April 1977, p. B7; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Paul Webster, "Giscard faces uproar over Zaire", The Guardian, 12 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Brezhnev Hits Zaire 'Meddling", The Hartford Courant (AP), 19 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Ogunbadejo, "Conflict in Africa" (1979), p. 226–227.

- ^ PaulWebster and Jonathan Steele, "Giscard denies new Vietnam", The Guardian, 13 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ John Palmer, "Belgium explains arms for Zaire", 13 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Robin Wright, "Zaire Rebels Seen Preparing to Open a New Front", Washington Post, 13 April 1977, accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Pygmy bowmen join drive on Zaire invaders", Chicago Tribune, 20 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Robin Wright, "Both Sides Nibble at Territory in Zaire's 'Termite War'", 20 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Michael T. Kaufman, "2 CAPTIVES DISPLAYED BY ZAIRE IN STADIUM: Crowd of 60,000 Calls for Death of Men Seized in South—They Tell of Training by Cubans", New York Times, 20 April 1977, p. 6; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ George C. Wilson, "Zaire Asks For Planeload Of Coca-Cola", Washington Post, 20 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Laura Parks, "Copper is queen of Zaire's Shaba", Tri–State Defender, 21 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest. "The towns will provide the operating base from which raids against the battle groups will be launched, if they can be found, more than likely the raids will degenerate into punitive expeditions against the village of Shaba province where that guerrilla battle groups might be suspected of receiving support."

- ^ "Mobutu Flies to Zaire Copper Belt To Visit Troops Fighting Invaders", New York Times (UPI), 24 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Mobutu's troops overwhelm rebels in surprise raid", The Guardian, 26 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zairean troops in push to border", The Guardian, 27 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Michael T. Kaufman, "Zaire Says Its Forces Recapture a Key Rail Center From Katangan Rebels; Little Resistance Reported", 26 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Gets $85 Million In Loans", Hartford Courant, 27 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Americans Reported Zaire-Bound", New York Times, 17 April 1977, p. 33; accessed via ProQuest .

- ^ Ernest Volkman, "'CIA links' with Zaire" The Guardian, 18 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest. "The Central Intelligence Agency is covertly supporting efforts now underway to recruit several hundred mercenaries in the United States and Britain to fight on behalf of President Mobutu of Zaire against Katanganese invaders. The CIA has strong links with a Californian who is in charge of the American recruitment, according to intelligence sources, and had backed the operation with funds. It also has passed word quietly to the US Justice Department that it will not cooperate in a pending investigation of the American recruiter's activities."

- ^ "Mercenaries' Recruiter denies link with C.I.A.", New York Times (AP), 20 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Tendayi Kumbula, "'Bad Boy' Mercenary Tells of Adventures", Los Angeles Times, 25 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Jonathan C. Randal, "Mobuto Riding High, But Possibility Raised Of Guerrilla Warfare", Washington Post, 28 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ a b David Lamb, "The Fall and Rise of the Zairian Empire: Mobuto's Game Plan Guides Country to Victory on the Back of Showmanship", Los Angeles Times, 18 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire reports Shaba fighting lull", Baltimore Sun, 6 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest. "In another development, four Western European ambassadors met with presidential aides and Foreign Ministry officials in attempts to convince the government to cancel plans to exhibit seven Western journalists arrested in Shaba last month. They have been accused of espionage and violating a ban on journalists in the province."

- ^ Colin Smith, "The closing doors of Africa", The Observer, 15 May 1977, p. 12; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Newsmen 'to go on show' in Zaire", The Guardian (UPI), 5 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ David Lamb, "Zaire Expels Seven Journalists Held as POWs", Los Angeles Times, 7 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "3 Moroccan Soldiers Executed for Rape", Hartford Courant (AP), 25 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Rape case soldiers executed", The Guardian, 25 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Robin Wright, "Tribesmen in Troubled Province Become Victims of Zaire Army", Washington Post, 21 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest. "There are several confirmed reports that six persons have been killed from beating or stabbing incidents and that the local detention centers hold at least 100 Africans. There are unconfirmed reports of other deaths and imprisonment. There are also widespread reports of Lunda families being repeatedly threatened if money, food or clothing is not provided to government troops. The campaign is apparently designed in part to discourage the Lunda people from cooperating with Katangan rebels who are also from the Lunda tribe, according to several highly reliable sources in Kolwezi. [...] The constant harassment and threats of bodily harm have further alienated already suspicious local residents to the point that a growing number of blacks and Europeans now openly say they would welcome the Katangans merely to avoid further incidents and increasing tribal friction."

- ^ David Lamb, "Zaire's War Now in Others' Hands: 4 Nations Filling Main Battle, Support Roles", Los Angeles Times, 4 May 1977, p. B1; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire's Troops Reported Ambushed", New York Times (UPI), 4 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "American workers to return to Zaire", Los Angeles Times, 28 April 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Reports Recapturing Strategic Town Near Angola", Los Angeles Times, 22 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire reports Shaba victory", Baltimore Sun, 22 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Geoffrey Godwell, "Mobutu, Morocco end threat in Shaba; big powers kept out", Christian Science Monitor, 24 May 1977, accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Morocco's Mission in Zaire War Is Over, Foreign Minister Says", Los Angeles Times, 24 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire resistance falls", Baltimore Sun, 27 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "War clouds threaten horn: Turmoil in Ethiopia altering area alliances", Baltimore Sun, 17 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "US says Cuban advisers in Ethiopia", Boston Globe, 26 May 1977, p. 17; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Says Saudis Gave War Aid", Washington Post, 21 July 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), pp. 80–81. "Towards the end of the crisis, Mobutu had declared that the Lunda people, from whom most of the rebels hailed, had 'no reason to fear any repression whatsoever from the armed forces of Zaire. But following the rebels' retreat, a well-informed journalist reported that 'the behavior of the Zairean army in Shaba was even more hateful than usual. Tens of thousands of Zaireans sought refuge in Angola, and all their testimonies agree: "the army has looted, robbed, raped. They have burned our villages and perpetrated wholesale massacres."'"

- ^ Gleijeses, "Truth or Credibility" (2010), p. 81.

- ^ a b "Zaire Condemns Two Men It Links to Shaba Invasion", New York Times, 19 August 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire's No. 2 Official Ousted, Will Face Charge of Treason", Washington Post, 14 August 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Treason charge shakes Zaire", The Guardian (AP), 15 August 1977, p. 6; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Zaire Aide Gets Death", Los Angeles Times, 13 September 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ "Former Zaire Aide, Guilty of Treason, Is Sentenced to Die", New York Times, 14 September 1977; accessed via ProQuest

- ^ "Mobutu reprieves former Minister", The Guardian, 16 September 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 34.

- ^ Odom, Shaba II (1993), p. 30.

- ^ Richard R. Leger, "The Other War: Conflict Is on Wane, But Zaire Still Fights Poverty, Bankruptcy: Lack of Foreign Exchange Plagues Overseas Firms; Mobutu in Firm Control", Wall Street Journal, 24 May 1977; accessed via ProQuest.

- ^ Tom Herman, "Major Loan to Zaire Up to $250 Million Nearing Completion", Wall Street Journal, 24 February 1978; accessed via ProQuest.

Bibliography

- Gleijeses, Piero. "Truth or Credibility: Castro, Carter, and the Invasions of Shaba". The International History Review 18(1), 2010. doi:10.1080/07075332.1996.9640737.

- Odom, Thomas P. Shaba II: The French and Belgian Intervention in Zaire in 1978. Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute, April 1993.

- Ogunbadejo, Oye. "Conflict in Africa: A Case Study of the Shaba Crisis, 1977". World Affairs 141(3), Winter 1979. JSTOR 20671780.

- Van Nederveen, Gilles K. USAF Airlift into the Heart of Darkness, the Congo 1960-1978: Implications for Modern Air Mobility Planners. Research Paper 2004–04. Airpower Research Institute; College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education; Air University. 2004.

Further reading

- Roger Glickson, 'The Shaba Crisis: Stumbling to Victory,' Small Wars and Insurgencies, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1994.