Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

-

(Top)

-

1 Etymology

-

2 History

-

3 Geography

-

4 Demographics

-

5 Economy and infrastructure

-

6 Transportation

-

7 Politics

-

8 Main sights

-

9 Shopping

-

10 Culture

-

10.1 The arts

-

10.2 Museums

-

10.2.1 Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

-

10.2.2 Anıtkabir

-

10.2.3 Ankara Ethnography Museum

-

10.2.4 State Art and Sculpture Museum

-

10.2.5 Cer Modern

-

10.2.6 War of Independence Museum

-

10.2.7 Mehmet Akif Literature Museum Library

-

10.2.8 TCDD Open Air Steam Locomotive Museum

-

10.2.9 Ankara Aviation Museum

-

10.2.10 METU Science and Technology Museum

-

-

10.3 Sports

-

-

11 Parks

-

12 Education

-

13 Fauna

-

14 International relations

-

15 See also

-

16 Notes

-

17 References

-

18 Further reading

-

19 External links

Ankara | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Heart of Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye'nin Kalbi) | |

| Coordinates: 39°55′48″N 32°51′00″E / 39.93000°N 32.85000°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Central Anatolia |

| Province | Ankara |

| Districts | 25 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mansur Yavaş (CHP) |

| • Governor | Vasip Şahin |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 4,130.2 km2 (1,594.7 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 25,632 km2 (9,897 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 938 m (3,077 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2023)[5] | |

| • Capital city and metropolitan municipality | 5,803,482 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Turkey |

| • Urban | 5,165,783 |

| • Urban density | 1,251/km2 (3,240/sq mi) |

| • Metro density | 237/km2 (610/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Ankaran (Turkish: Ankaralı) |

| GDP (nominal, 2022) | |

| • Capital city and metropolitan municipality | ₺ 1,330 billion US$ 81 billion |

| • Per capita | ₺ 230,677 US$ 13,919 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 06xxx |

| Area code | +90 312 |

| Vehicle registration | 06 |

| Website | www www |

Ankara[b] is the capital city of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and 5.8 million in Ankara Province.[5][4] Ankara is Turkey's second-largest city after Istanbul by population, first by urban area (4,130 km2), and third by metro area (25,632 km2).

Serving as the capital of the ancient Celtic state of Galatia (280–64 BC), and later of the Roman province with the same name (25 BC–7th century), Ankara has various Hattian, Hittite, Lydian, Phrygian, Galatian, Greek, Persian, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman archeological sites. Ankara was historically known as Ancyra[c] and Angora.[d][16] The Ottomans made the city the capital first of the Anatolia Eyalet (1393 – late 15th century) and then the Angora Eyalet (1827–1864) and the Angora Vilayet (1867–1922).

The historical center of Ankara is a rocky hill rising 150 m (500 ft) over the left bank of the Ankara River, a tributary of the Sakarya River. The hill remains crowned by the ruins of Ankara Castle. Although few of its outworks have survived, there are well-preserved examples of Roman and Ottoman architecture throughout the city, the most remarkable being the 20 BC Temple of Augustus and Rome that boasts the Monumentum Ancyranum, the inscription recording the Res Gestae Divi Augusti.[17]

On 23 April 1920, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey was established in Ankara, which became the headquarters of the Turkish National Movement during the Turkish War of Independence. Ankara became the new Turkish capital upon the establishment of the Republic on 29 October 1923, succeeding in this role as the former Turkish capital Istanbul following the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The government is a prominent employer, but Ankara is also an important commercial and industrial city located at the center of Turkey's road and railway networks. The city gave its name to the Angora wool shorn from Angora rabbits, the long-haired Angora goat (the source of mohair), and the Angora cat. The area is also known for its pears, honey and Muscat grapes. Although situated in one of the driest regions of Turkey and surrounded mostly by steppe vegetation (except for the forested areas on the southern periphery), Ankara can be considered a green city in terms of green areas per inhabitant, at 72 square meters (775 square feet) per head.[18]

Etymology

The orthography of the name Ankara[19] has varied over the ages. It has been identified with the Hittite cult center Ankuwaš,[20][21] although this remains a matter of debate.[22] In classical antiquity and during the medieval period, the city was known as Ánkyra (Ἄγκυρα, lit "anchor") in Greek and Ancyra in Latin; the Galatian Celtic name was probably a similar variant. Following its annexation by the Seljuk Turks in 1073, the city became known in many European languages as Angora; it was also known in Ottoman Turkish as Engürü (انگورو).[23][17] The form "Angora" is preserved in the names of breeds of many different kinds of animals, and in the names of several locations in the US (see Angora).

History

The region's history can be traced back to the Bronze Age Hattic civilization, which was succeeded in the 2nd millennium BC by the Hittites, in the 10th century BC by the Phrygians, and later by the Lydians, Persians, Greeks, Galatians, Romans, Byzantines, and Turks (the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm, the Ottoman Empire and finally republican Türkiye).

Ancient history

The oldest settlements in and around the city center of Ankara belonged to the Hattic civilization which existed during the Bronze Age and was gradually absorbed c. 2000 – 1700 BC by the Indo-European Hittites. The city grew significantly in size and importance under the Phrygians starting around 1000 BC, and experienced a large expansion following the mass migration from Gordion, (the capital of Phrygia), after an earthquake which severely damaged that city around that time. In Phrygian tradition, King Midas was venerated as the founder of Ancyra, but Pausanias mentions that the city was actually far older, which accords with present archeological knowledge.[24]

Phrygian rule was succeeded first by Lydian and later by Persian rule, though the strongly Phrygian character of the peasantry remained, as evidenced by the gravestones of the much later Roman period. Persian sovereignty lasted until the Persians' defeat at the hands of Alexander the Great who conquered the city in 333 BC. Alexander came from Gordion to Ankara and stayed in the city for a short period. After his death at Babylon in 323 BC and the subsequent division of his empire among his generals, Ankara, and its environs fell into the share of Antigonus.

Another important expansion took place under the Greeks of Pontos who came there around 300 BC and developed the city as a trading center for the commerce of goods between the Black Sea ports and Crimea to the north; Assyria, Cyprus, and Lebanon to the south; and Georgia, Armenia and Persia to the east.[citation needed] By that time[citation needed] the city also took its name Ἄγκυρα (Ánkyra, meaning anchor in Greek) which, in slightly modified form, provides the modern name of Ankara.

Celtic history

In 278 BC, the city, along with the rest of central Anatolia, was occupied by a Celtic group, the Galatians, who were the first to make Ankara one of their main tribal centers, the headquarters of the Tectosages tribe.[25] Other centers were Pessinus, today's Ballıhisar, for the Trocmi tribe, and Tavium, to the east of Ankara, for the Tolistobogii tribe. The city was then known as Ancyra. The Celtic element was probably relatively small in numbers; a warrior aristocracy which ruled over Phrygian-speaking peasants. However, the Celtic language continued to be spoken in Galatia for many centuries. At the end of the 4th century, St. Jerome, a native of Dalmatia, observed that the language spoken around Ankara was very similar to that being spoken in the northwest of the Roman world near Trier.

Roman history

The city was subsequently passed under the control of the Roman Empire. In 25 BC, Emperor Augustus raised it to the status of a polis and made it the capital city of the Roman province of Galatia.[26] Ankara is famous for the Monumentum Ancyranum (Temple of Augustus and Rome) which contains the official record of the Acts of Augustus, known as the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, an inscription cut in marble on the walls of this temple. The ruins of Ancyra still furnish today valuable bas-reliefs, inscriptions and other architectural fragments. Two other Galatian tribal centers, Tavium near Yozgat, and Pessinus (Balhisar) to the west, near Sivrihisar, continued to be reasonably important settlements in the Roman period, but it was Ancyra that grew into a grand metropolis.

An estimated 200,000 people lived in Ancyra in good times during the Roman Empire, a far greater number than was to be the case from after the fall of the Roman Empire until the early 20th century. The small Ankara River ran through the center of the Roman town. It has now been covered and diverted, but it formed the northern boundary of the old town during the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman periods. Çankaya, the rim of the majestic hill to the south of the present city center, stood well outside the Roman city, but may have been a summer resort. In the 19th century, the remains of at least one Roman villa or large house were still standing not far from where the Çankaya Presidential Residence stands today. To the west, the Roman city extended until the area of the Gençlik Park and Railway Station, while on the southern side of the hill, it may have extended downward as far as the site presently occupied by Hacettepe University. It was thus a sizeable city by any standards and much larger than the Roman towns of Gaul or Britannia.[citation needed]

Ancyra's importance rested on the fact that it was the junction point where the roads in northern Anatolia running north–south and east–west intersected, giving it major strategic importance for Rome's eastern frontier.[26] The great imperial road running east passed through Ankara and a succession of emperors and their armies came this way. They were not the only ones to use the Roman highway network, which was equally convenient for invaders. In the second half of the 3rd century, Ancyra was invaded in rapid succession by the Goths coming from the west (who rode far into the heart of Cappadocia, taking slaves and pillaging) and later by the Arabs. For about a decade, the town was one of the western outposts of one of Palmyrean empress Zenobia in the Syrian Desert, who took advantage of a period of weakness and disorder in the Roman Empire to set up a short-lived state of her own.

The town was reincorporated into the Roman Empire under Emperor Aurelian in 272. The tetrarchy, a system of multiple (up to four) emperors introduced by Diocletian (284–305), seems to have engaged in a substantial program of rebuilding and of road construction from Ancyra westwards to Germe and Dorylaeum (now Eskişehir).

In its heyday, Roman Ancyra was a large market and trading center but it also functioned as a major administrative capital, where a high official ruled from the city's Praetorium, a large administrative palace or office. During the 3rd century, life in Ancyra, as in other Anatolian towns, seems to have become somewhat militarized in response to the invasions and instability of the town.

Byzantine history

The city is well known during the 4th century as a center of Christian activity (see also below), due to frequent imperial visits, and through the letters of the pagan scholar Libanius.[26] Bishop Marcellus of Ancyra and Basil of Ancyra were active in the theological controversies of their day, and the city was the site of no fewer than three church synods in 314, 358 and 375, the latter two in favor of Arianism.[26]

The city was visited by Emperor Constans I (r. 337–350) in 347 and 350, Julian (r. 361–363) during his Persian campaign in 362, and Julian's successor Jovian (r. 363–364) in winter 363/364 (he entered his consulship while in the city). After Jovian's death soon after, Valentinian I (r. 364–375) was acclaimed emperor at Ancyra, and in the next year his brother Valens (r. 364–378) used Ancyra as his base against the usurper Procopius.[26] When the province of Galatia was divided sometime in 396/99, Ancyra remained the civil capital of Galatia I, as well as its ecclesiastical center (metropolitan see).[26] Emperor Arcadius (r. 383–408) frequently used the city as his summer residence, and some information about the ecclesiastical affairs of the city during the early 5th century is found in the works of Palladius of Galatia and Nilus of Ancyra.[26]

In 479, the rebel Marcian attacked the city, without being able to capture it.[26] In 610/11, Comentiolus, brother of Emperor Phocas (r. 602–610), launched his own unsuccessful rebellion in the city against Heraclius (r. 610–641).[26] Ten years later, in 620 or more likely 622, it was captured by the Sassanid Persians during the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. Although the city returned to Byzantine hands after the end of the war, the Persian presence left traces in the city's archeology, and likely began the process of its transformation from a late antique city to a medieval fortified settlement.[26]

In 654, the city, also known in Arabic sources as Qalat as-Salasil ("fortress of the chains"),[27] was captured for the first time by the Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate, under Muawiyah, the future founder of the Umayyad Caliphate.[26] At about the same time, the themes were established in Anatolia, and Ancyra became capital of the Opsician Theme, which was the largest and most important theme until it was split up under Emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775); Ancyra then became the capital of the new Bucellarian Theme.[26] The city was captured at least temporarily by the Umayyad prince Maslama ibn Hisham in 739/40, the last of the Umayyads' territorial gains from the Byzantine Empire.[28] Ancyra was attacked without success by Abbasid forces in 776 and in 798/99. In 805, Emperor Nikephoros I (r. 802–811) strengthened its fortifications, a fact which probably saved it from sack during the large-scale invasion of Anatolia by Caliph Harun al-Rashid in the next year.[26] Arab sources report that Harun and his successor al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833) took the city, but this information is later invention. In 838, however, during the Amorium campaign, the armies of Caliph al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842) converged and met at the city; abandoned by its inhabitants, Ancara was razed to the ground, before the Arab armies went on to besiege and destroy Amorium reaching as far as Smyrna.[26] In 859, Emperor Michael III (r. 842–867) came to the city during a campaign against the Arabs, and ordered its fortifications restored.[26] In 872, the city was menaced, but not taken, by the Paulicians under Chrysocheir.[26] The last Arab raid to reach the city was undertaken in 931, by the Abbasid governor of Tarsus, Thamal al-Dulafi, but the city again was not captured.[26]

Ecclesiastical history

Early Christian martyrs of Ancyra, about whom little is known, included Proklos and Hilarios who were natives of the otherwise unknown nearby village of Kallippi, and suffered repression under the emperor Trajan (98–117). In the 280s we hear of Philumenos, a Christian corn merchant from southern Anatolia, being captured and martyred in Ankara, and Eustathius.

As in other Roman towns, the reign of Diocletian marked the culmination of the persecution of the Christians. In 303, Ancyra was one of the towns where the co-emperors Diocletian and his deputy Galerius launched their anti-Christian persecution. In Ancyra, their first target was the 38-year-old Bishop of the town, whose name was Clement. Clement's life describes how he was taken to Rome, then sent back, and forced to undergo many interrogations and hardship before he, and his brother, and various companions were put to death. The remains of the church of St. Clement can be found today in a building just off Işıklar Caddesi in the Ulus district. Quite possibly this marks the site where Clement was originally buried. Four years later, a doctor of the town named Plato and his brother Antiochus also became celebrated martyrs under Galerius. Theodotus of Ancyra is also venerated as a saint.

However, the persecution proved unsuccessful and in 314 Ancyra was the center of an important council of the early church;[29] its 25 disciplinary canons constitute one of the most important documents in the early history of the administration of the Sacrament of Penance.[29] The synod also considered ecclesiastical policy for the reconstruction of the Christian Church after the persecutions, and in particular the treatment of lapsi—Christians who had given in to forced paganism (sacrifices) to avoid martyrdom during these persecutions.[29]

Though paganism was probably tottering in Ancyra in Clement's day, it may still have been the majority religion. Twenty years later, Christianity and monotheism had taken its place. Ancyra quickly turned into a Christian city, with a life dominated by monks and priests and theological disputes. The town council or senate gave way to the bishop as the main local figurehead. During the middle of the 4th century, Ancyra was involved in the complex theological disputes over the nature of Christ, and a form of Arianism seems to have originated there.[30]

In 362–363, Emperor Julian passed through Ancyra on his way to an ill-fated campaign against the Persians, and according to Christian sources, engaged in a persecution of various holy men.[31] The stone base for a statue, with an inscription describing Julian as "Lord of the whole world from the British Ocean to the barbarian nations", can still be seen, built into the eastern side of the inner circuit of the walls of Ankara Castle. The Column of Julian which was erected in honor of the emperor's visit to the city in 362 still stands today. In 375, Arian bishops met at Ancyra and deposed several bishops, among them St. Gregory of Nyssa.

In the late 4th century, Ancyra became something of an imperial holiday resort. After Constantinople became the East Roman capital, emperors in the 4th and 5th centuries would retire from the humid summer weather on the Bosporus to the drier mountain atmosphere of Ancyra. Theodosius II (408–450) kept his court in Ancyra in the summers. Laws issued in Ancyra testify to the time they spent there.

The Metropolis of Ancyra continued to be a residential see of the Eastern Orthodox Church until the 20th century, with about 40,000 faithful, mostly Turkish-speaking, but that situation ended as a result of the 1923 Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations. The earlier Armenian genocide put an end to the residential eparchy of Ancyra of the Armenian Catholic Church, which had been established in 1850.[32][33] It is also a titular metropolis of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Both the Ancient Byzantine Metropolitan archbishopric and the 'modern' Armenian eparchy are now listed by the Catholic Church as titular sees,[34] with separate apostolic successions.

Seljuk and Ottoman history

After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuk Turks overran much of Anatolia. By 1073, the Turkish settlers had reached the vicinity of Ancyra, and the city was captured shortly after, at the latest by the time of the rebellion of Nikephoros Melissenos in 1081.[26] In 1101, when the Crusade under Raymond IV of Toulouse arrived, the city had been under Danishmend control for some time. The Crusaders captured the city, and handed it over to the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118).[26] Byzantine rule did not last long, and the city was captured by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum at some unknown point; in 1127, it returned to Danishmend control until 1143, when the Seljuks of Rum retook it.[26]

After the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243, in which the Mongols defeated the Seljuks, most of Anatolia became part of the dominion of the Mongols. Taking advantage of Seljuk decline, a semi-religious cast of craftsmen and trade people named Ahiler chose Angora as their independent city-state in 1290. Orhan, the second Bey of the Ottoman Empire, captured the city in 1356. Timur defeated Bayezid I at the Battle of Ankara in 1402 and took the city, but in 1403 Angora was again under Ottoman control.

The Levant Company maintained a factory in the town from 1639 to 1768.[17] In the 19th century, its population was estimated at 20,000 to 60,000.[23] It was sacked by Egyptians under Ibrahim Pasha in 1832.[17]

From 1867 to 1922, the city served as the capital of the Angora Vilayet, which included most of ancient Galatia.

Prior to World War I, the town had a British consulate and a population of around 28,000, roughly 1⁄3 of whom were Christian.[17]

Turkish republican capital

Following the Ottoman defeat in World War I, the Ottoman capital Constantinople (modern Istanbul) and much of Anatolia was occupied by the Allies, who planned to share these lands between Armenia, France, Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom, leaving for the Turks the core piece of land in central Anatolia. In response, the leader of the Turkish nationalist movement, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, established the headquarters of his resistance movement in Angora in 1920. After the Turkish War of Independence was won and the Treaty of Sèvres was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), the Turkish nationalists replaced the Ottoman Empire with the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923. A few days earlier, Angora had officially replaced Constantinople as the new Turkish capital city, on 13 October 1923,[35] and Republican officials declared that the city's name is Ankara.[36]

After Ankara became the capital of the newly founded Republic of Turkey, new development divided the city into an old section, called Ulus, and a new section, called Yenişehir. Ancient buildings reflecting Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman history and narrow winding streets mark the old section. The new section, now centered on Kızılay Square, has the trappings of a more modern city: wide streets, hotels, theaters, shopping malls, and high-rises.

Government offices and foreign embassies are also located in the new section. Ankara has experienced a phenomenal growth since it was made Turkey's capital in 1923, when it was "a small town of no importance".[38] In 1924, the year after the government had moved there, Ankara had about 35,000 residents. By 1927 there were 44,553 residents and by 1950 the population had grown to 286,781. After 1930, the city officially became known in Western languages as Ankara. By the late 1930s, the English name "Angora" was no longer in popular use.[39]

Ankara continued to grow rapidly during the latter half of the 20th century and eventually outranked İzmir as Turkey's second-largest city, after Istanbul. Ankara's urban population reached 4,587,558 in 2014, while the population of Ankara Province reached 5,150,072 in 2015.[40]

The Presidential Palace of Türkiye is situated in Ankara. This building serves as the main residence of the president.

Geography

Geographically, Ankara is located in the middle of the Kızılırmak and Sakarya rivers, and the Sakarya River forms its border with Eskişehir in the west. Ankara shares its borders with Bolu and Çankırı in the north; Konya in the south and Kırıkkale in the east.[42]

Ankara and its province are located in the Central Anatolia Region of Turkey. The Çubuk Brook flows through the city center of Ankara. It is connected in the western suburbs of the city to the Ankara River, which is a tributary of the Sakarya River.

Climate

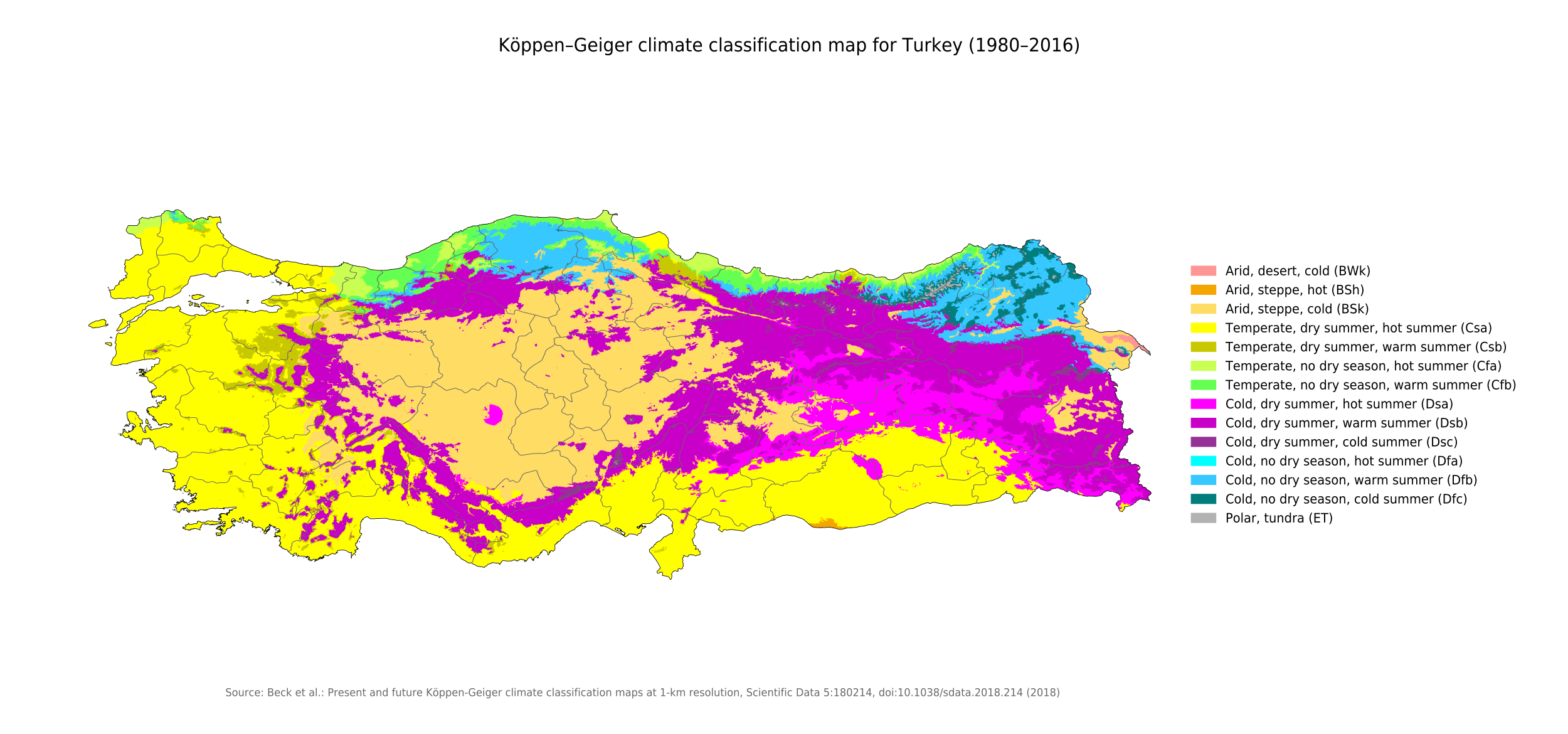

Ankara has a cold semi-arid climate under the Köppen climate classification (BSk), while under the Trewartha climate classification, the city is classified as humid continental (Dc). Due to its elevation and inland location, Ankara has cold and snowy winters, and hot and dry summers. Rainfall occurs mostly during the spring and autumn. The city lies in USDA Hardiness zone 7b, and its annual average precipitation is fairly low at 414 millimeters (16 in), nevertheless precipitation can be observed throughout the year. Monthly mean temperatures range from 0.9 °C (33.6 °F) in January to 24.3 °C (75.7 °F) in July, with an annual mean of 12.6 °C (54.7 °F).[43] Ankara's overall temperature regime is very similar to New York City.

| Climate data for Ankara (Turkish State Meteorological Service Compound, Keçiören), 1991–2020, extremes 1927–2021 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.0 (98.6) |

41.0 (105.8) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.1 (102.4) |

33.3 (91.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.9 (−12.8) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−19.2 (−2.6) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.6 (1.52) |

36.6 (1.44) |

46.9 (1.85) |

44.5 (1.75) |

51.0 (2.01) |

40.2 (1.58) |

14.8 (0.58) |

14.6 (0.57) |

17.9 (0.70) |

33.4 (1.31) |

31.9 (1.26) |

43.2 (1.70) |

413.6 (16.28) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.60 | 12.67 | 13.87 | 13.40 | 14.53 | 11.47 | 4.60 | 5.10 | 5.50 | 9.23 | 8.93 | 14.00 | 126.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.7 | 70.7 | 63.2 | 58.4 | 56.3 | 53.1 | 45.5 | 45.3 | 48.8 | 60.2 | 68.6 | 76.7 | 60.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 68.2 | 101.7 | 148.8 | 189.0 | 238.7 | 279.0 | 328.6 | 316.2 | 264.0 | 195.3 | 129.0 | 74.4 | 2,332.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.2 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 6.4 |

| Source 1: Turkish State Meteorological Service[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity, 1991–2020)[44] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 4,466,756 | — |

| 2012 | 4,965,542 | +2.14% |

| 2017 | 5,445,026 | +1.86% |

| 2022 | 5,782,285 | +1.21% |

| Source: TÜİK[45] | ||

Ankara had a population of 75,000 in 1927. There were 74,632 male residents and 48,882 female residents in Ankara according to the 1935 census.[46] As of 2022, the population of the Ankara Province was 5,782,285.[45] When Ankara became the capital of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, it was designated as a planned city for 500,000 future inhabitants. During the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, the city grew in a planned and orderly pace. However, from the 1950s onward, the city grew much faster than envisioned, because unemployment and poverty forced people to migrate from the countryside into the city to seek a better standard of living. As a result, many illegal houses called gecekondu were built around the city, causing the unplanned and uncontrolled urban landscape of Ankara, as not enough planned housing could be built fast enough. Although precariously built, the vast majority of them have electricity, running water and modern household amenities.

Nevertheless, many of these gecekondus have been replaced by huge public housing projects in the form of tower blocks such as Elvankent, Eryaman and Güzelkent; and also as mass housing compounds for military and civil service accommodation. Although many gecekondus still remain, they too are gradually being replaced by mass housing compounds, as empty land plots in the city of Ankara for new construction projects are becoming impossible to find.

Çorum and Yozgat, which are located in Central Anatolia and whose population is decreasing, are the provinces with the highest net migration to Ankara.[47] About one third of the Central Anatolia population of 15,608,868 people resides in Ankara.

The literacy rate in the whole province for people who are 15 years old or older is 98.18% according to 2020 TÜİK data. Ankara Province also has the highest percentage of tertiary education graduates in Turkey with 29.08% of the population having either an undergraduate, master's or doctor's degree.[48]

Economy and infrastructure

Ankara has long been a productive agricultural region in Anatolia. In the Ottoman period, Ankara was well known for producing grain, cotton, and fruits.[49]

The city has exported mohair (from the Angora goat) and Angora wool (from the Angora rabbit) internationally for centuries. In the 19th century, the city also exported substantial amounts of goat and cat skins, gum, wax, honey, berries, and madder root.[23] It was connected to Istanbul by railway before the First World War, continuing to export mohair, wool, berries, and grain.[17]

The Central Anatolia Region is one of the primary locations of grape and wine production in Turkey, and Ankara is particularly famous for its Kalecik Karası and Muscat grapes; and its Kavaklıdere wine, which is produced in the Kavaklıdere neighborhood within the Çankaya district of the city. Ankara is also famous for its pears. Another renowned natural product of Ankara is its indigenous type of honey (Ankara Balı) which is known for its light color and is mostly produced by the Atatürk Forest Farm and Zoo in the Gazi district, and by other facilities in the Elmadağ, Çubuk and Beypazarı districts. Çubuk-1 and Çubuk-2 dams on the Çubuk Brook in Ankara were among the first dams constructed in the Turkish Republic.

Ankara is the center of the state-owned and private Turkish defence and aerospace companies, where the industrial plants and headquarters of the Turkish Aerospace Industries, MKE, ASELSAN, HAVELSAN, ROKETSAN, FNSS,[52] Nurol Makina,[53] and numerous other firms are located. Exports to foreign countries from these defense and aerospace firms have steadily increased in the past decades. The IDEF in Ankara is one of the largest international expositions of the global arms industry. A number of the global automotive companies also have production facilities in Ankara, such as the German bus and truck manufacturer MAN SE.[54] Ankara hosts the OSTIM Industrial Zone, Turkey's largest industrial park.

A large percentage of the complicated employment in Ankara is provided by the state institutions; such as the ministries, subministries, and other administrative bodies of the Turkish government. There are also many foreign citizens working as diplomats or clerks in the embassies of their respective countries.

Transportation

The Electricity, Gas, Bus General Directorate (EGO)[55] operates the Ankara Metro and other forms of public transportation. Ankara is served by a suburban rail named Başkentray (B1) and five Metro lines (A1, M1, M2, M3, M4) of the Ankara Metro with about 400,000 total daily commuters, while additional subway lines (A2 and M2a/b) are under construction. A 3.2 km (2.0 mi) long gondola lift with four stations connects the district of Şentepe to the Yenimahalle metro station.[56]

The Ankara Central Station is a major rail hub in Turkey. The Turkish State Railways operates passenger train service from Ankara to other major cities, such as: Istanbul, Eskişehir, Balıkesir, Kütahya, İzmir, Kayseri, Adana, Kars, Elazığ, Malatya, Diyarbakır, Karabük, Zonguldak and Sivas. Commuter rail also runs between the stations of Sincan and Kayaş. On 13 March 2009, the new Yüksek Hızlı Tren (YHT) high-speed rail service began operation between Ankara and Eskişehir. On 23 August 2011, another YHT high-speed line commercially started its service between Ankara and Konya. On 25 July 2014, the Ankara–Istanbul high-speed line of YHT entered service.[57]

Esenboğa International Airport, located in the north-east of the city, is Ankara's main airport.

Ankara public transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting on public transit in Ankara on a weekday is 71 minutes. 17% of public transit passengers, ride for more than two hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is sixteen minutes, while 28% of users wait for over twenty minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 9.9 km (6.2 mi), while 27% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[58]

Politics

Since 8 April 2019, the mayor of Ankara is Mansur Yavaş from the Republican People's Party (CHP), who won the mayoral election in 2019 and 2024.

Ankara is politically a triple battleground between the ruling conservative AK Party, the opposition Kemalist center-left Republican People's Party (CHP) and the nationalist far-right MHP. The province of Ankara is divided into 25 districts. Historically, the CHP's key and almost only political stronghold in Ankara lied within the central area of Çankaya, which is the city's most populous district. While the CHP has always gained between 60 and 70% of the vote in Çankaya since 2002, political support elsewhere throughout Ankara was minimal. The high population within Çankaya, as well as Yenimahalle to an extent, has allowed the CHP to take overall second place behind the AK Party in both local and general elections, with the MHP a close third, despite the fact that the MHP was politically stronger than the CHP in almost every other district. Overall, the AK Party enjoyed the most support throughout the city. The electorate of Ankara thus tended to vote in favor of the political right, far more so than the other main cities of Istanbul and İzmir. In retrospect, the 2013–14 protests against the AK Party government were particularly strong in Ankara, proving to be fatal on multiple occasions.[59]

Ankara district Municipalities Local elections, 2024 | |

|---|---|

| CHP | 16 / 25

|

| AK Party | 8 / 25

|

| Independent | 1 / 25 |

The city suffered from a series of terrorist attacks in 2015 and 2016, most notably on 10 October 2015; 17 February 2016; and 13 March 2016. The city was also one of the sites of the coup attempt on 15 July 2016.

Melih Gökçek was the Metropolitan Mayor of Ankara between 1994 and 2017. Initially elected in the 1994 local elections, he was re-elected in 1999, 2004 and 2009. In the 2014 local elections, Gökçek stood for a fifth term. The MHP's metropolitan mayoral candidate for the 2009 local elections, Mansur Yavaş, stood as the CHP's candidate against Gökçek in 2014. In a heavily controversial election, Gökçek was declared the winner by just 1% ahead of Yavaş amid allegations of systematic electoral fraud. With the Supreme Electoral Council and courts rejecting his appeals, Yavaş declared his intention to take the irregularities to the European Court of Human Rights. Although Gökçek was inaugurated for a fifth term, most election observers believe[60] that Yavaş was the winner of the election.[61][62][63][64][65] Gökçek resigned on 28 October 2017 and was replaced by the former mayor of Sincan district, Mustafa Tuna; who was succeeded by Mansur Yavaş of the CHP, the current mayor of Ankara, elected in 2019.

Main sights

Ancient/archeological sites

Ankara Citadel

The foundations of the Ankara castle and citadel were laid by the Galatians on a prominent lava outcrop (39°56′28″N 32°51′50″E / 39.941°N 32.864°E), and the rest was completed by the Romans. The Byzantines and Seljuks further made restorations and additions. The area around and inside the citadel, being the oldest part of Ankara, contains many fine examples of traditional architecture. There are also recreational areas to relax. Many restored traditional Turkish houses inside the citadel area have found new life as restaurants, serving local cuisine.

The citadel was depicted in various Turkish banknotes during 1927–1952 and 1983–1989.[66]

Roman Theater

The remains, the stage, and the backstage of the Roman theater can be seen outside the castle. Roman statues that were found here are exhibited in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. The seating area is still under excavation.

Temple of Augustus and Rome

The Augusteum,[67] now known as the Temple of Augustus and Rome, was built 25 x 20 BC following the conquest of Central Anatolia by the Roman Empire. Ancyra then formed the capital of the new province of Galatia. After the death of Augustus in AD 14, a copy of the text of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (the Monumentum Ancyranum) was inscribed on the interior of the temple's pronaos in Latin and a Greek translation on an exterior wall of the cella. The temple on the ancient acropolis of Ancyra was enlarged in the 2nd century and converted into a church in the 5th century. It is located in the Ulus quarter of the city. It was subsequently publicized by the Austrian ambassador Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq in the 16th century.

Roman Baths

The Roman Baths of Ankara have all the typical features of a classical Roman bath complex: a frigidarium (cold room), a tepidarium (warm room) and a caldarium (hot room). The baths were built during the reign of the Roman emperor Caracalla in the early 3rd century to honor Asclepios, the God of Medicine. Today, only the basement and first floors remain. It is situated in the Ulus quarter.

Roman Road

The Roman Road of Ankara or Cardo Maximus was found in 1995 by Turkish archeologist Cevdet Bayburtluoğlu. It is 216 meters (709 feet) long and 6.7 meters (22.0 feet) wide. Many ancient artifacts were discovered during the excavations along the road and most of them are displayed at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations.[68][69]

Column of Julian

The Column of Julian or Julianus, now in the Ulus district, was erected in honor of the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate's visit to Ancyra in 362.

Mosques

Kocatepe Mosque

Kocatepe Mosque is the largest mosque in the city. Located in the Kocatepe quarter, it was constructed between 1967 and 1987 in classical Ottoman style with four minarets. Its size and prominent location have made it a landmark for the city.

Ahmet Hamdi Akseki Mosque

Ahmet Hamdi Akseki Mosque is located near the Presidency of Religious Affairs on the Eskişehir Road. Built in the Turkish neoclassical style, it is one of the largest new mosques in the city, completed and opened in 2013. It can accommodate 6 thousand people during general prayers, and up to 30 thousand people during funeral prayers. The mosque was decorated with Anatolian Seljuk style patterns.[70]

Yeni (Cenab Ahmet) Mosque

It is the largest Ottoman mosque in Ankara and was built by the famous architect Sinan in the 16th century. The mimber (pulpit) and mihrap (prayer niche) are of white marble, and the mosque itself is of Ankara stone, an example of very fine workmanship.

Hacı Bayram Mosque

This mosque, in the Ulus quarter next to the Temple of Augustus, was built in the early 15th century in Seljuk style by an unknown architect. It was subsequently restored by architect Mimar Sinan in the 16th century, with Kütahya tiles being added in the 18th century. The mosque was built in honor of Hacı Bayram-ı Veli, whose tomb is next to the mosque, two years before his death (1427–28).[71] The usable space inside this mosque is 437 m2 (4,704 sq ft) on the first floor and 263 m2 (2,831 sq ft) on the second floor.

Ahi Elvan Mosque

It was founded in the Ulus quarter near the Ankara Citadel and was constructed by the Ahi fraternity during the late 14th and early 15th centuries. The finely carved walnut mimber (pulpit) is of particular interest.[72]

Alâeddin Mosque

The Alâeddin Mosque is the oldest mosque in Ankara. It has a carved walnut mimber, the inscription on which records that the mosque was completed in early AH 574 (which corresponds to the summer of 1178 AD) and was built by the Seljuk prince Muhiddin Mesud Şah (died 1204), the Bey of Ankara, who was the son of the Anatolian Seljuk sultan Kılıç Arslan II (reigned 1156–1192.)

Modern monuments

Victory Monument

Bottom: Hittite Sun Course Monument (1978)

The Victory Monument (Turkish: Zafer Anıtı) was crafted by Austrian sculptor Heinrich Krippel in 1925 and was erected in 1927 at Ulus Square. The monument is made of marble and bronze and features an equestrian statue of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who wears a Republic era modern military uniform, with the rank Field Marshal.[73]

Statue of Atatürk

Located at Zafer(Victory) Square (Turkish: Zafer Meydanı), the marble and bronze statue was crafted by the renowned Italian sculptor Pietro Canonica in 1927 and depicts a standing Atatürk who wears a Republic era modern military uniform, with the rank Field Marshal.

Monument to a Secure, Confident Future

This monument, located in Güvenpark near Kızılay Square, was erected in 1935 and bears Atatürk's advice to his people: "Turk! Be proud, work hard, and believe in yourself." (There is debate on whether or not Atatürk actually said "Use your mind"(Turkish: öğün) instead of "Be proud"(Turkish: övün))[74]

The monument was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 5 lira banknote of 1937–1952[75] and of the 1000 lira banknotes of 1939–1946.[76]

Hatti Monument

Erected in 1978 at Sıhhiye Square, this impressive monument symbolizes the Hatti Sun Disc (which was later adopted by the Hittites) and commemorates Anatolia's earliest known civilization. The Hatti Sun Disc has been used in the previous logo of Ankara Metropolitan Municipality. It was also used in the previous logo of the Ministry of Culture & Tourism.

Inns

Suluhan

Suluhan is a historical Inn in Ankara. It is also called the Hasanpaşa Han. It is about 400 meters (1,300 ft) southeast of Ulus Square and situated in the Hacıdoğan neighborhood. According to the vakfiye (inscription) of the building, the Ottoman era han was commissioned by Hasan Pasha, a regional beylerbey, and was constructed between 1508 and 1511, during the final years of the reign of Sultan Bayezid II.[77] There are 102 rooms (now shops) which face the two yards.[78] In each room there is a window, a niche and a chimney.[79]

Çengelhan Rahmi M. Koç Museum

Çengelhan Rahmi M. Koç Museum is a museum of industrial technology situated in Çengel Han, an Ottoman era Inn which was completed in 1523, during the early years of the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The exhibits include industrial/technological artifacts from the 1850s onwards. There are also sections about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey; Vehbi Koç, Rahmi Koç's father and one of the first industrialists of Turkey, and Ankara city.

Shopping

Foreign visitors to Ankara usually like to visit the old shops in Çıkrıkçılar Yokuşu (Weavers' Road) near Ulus, where myriad things ranging from traditional fabrics, hand-woven carpets and leather products can be found at bargain prices. Bakırcılar Çarşısı (Bazaar of Coppersmiths) is particularly popular, and many interesting items, not just of copper, can be found here like jewelry, carpets, costumes, antiques and embroidery. Up the hill to the castle gate, there are many shops selling a huge and fresh collection of spices, dried fruits, nuts, and other produce.

Modern shopping areas are mostly found in Kızılay, or on Tunalı Hilmi Avenue, including the modern mall of Karum (named after the ancient Assyrian merchant colonies called Kârum that were established in central Anatolia at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC) which is located towards the end of the Avenue; and in Çankaya, the quarter with the highest elevation in the city. Atakule Tower next to Atrium Mall in Çankaya has views over Ankara and also has a revolving restaurant at the top. The symbol of the Armada Shopping Mall is an anchor, and there's a large anchor monument at its entrance, as a reference to the ancient Greek name of the city, Ἄγκυρα (Ánkyra), which means anchor. Likewise, the anchor monument is also related with the Spanish name of the mall, Armada, which means naval fleet.

As Ankara started expanding westward in the 1970s, several modern, suburbia-style developments, mini-cities and business districts such as Söğütözü began to rise along the western highway, also known as the Eskişehir Road. The Armada, CEPA and Kentpark malls on the highway, the Galleria, Arcadium and Gordion in Ümitköy, and a huge mall, Real in Bilkent Center, offer North American and European style shopping opportunities (these places can be reached through the Eskişehir Highway.) There is also the newly expanded ANKAmall at the outskirts, on the Istanbul Highway, which houses most of the well-known international brands. This mall is the largest throughout the Ankara region. In 2014, a few more shopping malls were open in Ankara. They are Next Level and Taurus on the Boulevard of Mevlana (also known as Konya Road).

Culture

The arts

Turkish State Opera and Ballet, the national directorate of opera and ballet companies of Turkey, has its headquarters in Ankara, and serves the city with three venues:

- Ankara Opera House (Opera Sahnesi, also known as Büyük Tiyatro) is the largest of the three venues for opera and ballet in Ankara.

Music

Ankara is host to five classical music orchestras:

- Presidential Symphony Orchestra (Turkish Presidential Symphony Orchestra)

- Bilkent Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is a major symphony orchestra of Turkey.

- Hacettepe Symphony Orchestra was founded in 2003 and directed by Erol Erdinç

- Başkent Oda Orkestrası (Chamber Orchestra of the Capital)[80]

There are four concert halls in the city:

- CSO Concert Hall

- Bilkent Concert Hall is a performing arts center in Ankara. It is located in the Bilkent University campus.

- MEB Şura Salonu (also known as the Festival Hall), It is noted for its tango performances.

- Çankaya Çağdaş Sanatlar Merkezi Concert Hall was founded in 1994.

The city has been host to several well-established, annual theater, music, film festivals:

- Ankara International Music Festival, a music festival organized in the Turkish capital presenting classical music and ballet programs.

Ankara also has a number of concert venues such as Eskiyeni, IF Performance Hall, Jolly Joker, Kite, Nefes Bar, and Route, which host the live performances and events of popular musicians.

Theater

The Turkish State Theatres also has its head office in Ankara and runs the following stages in the city:

In addition, the city is served by several private theater companies, among which Ankara Sanat Tiyatrosu, who have their own stage in the city center, is a notable example.

Museums

There are about 50 museums in the city.

Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations (Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi) is situated at the entrance of the Ankara Castle. It is an old 15th century bedesten (covered bazaar)[81] that has been restored and now houses a collection of Paleolithic, Neolithic, Hatti, Hittite, Phrygian, Urartian and Roman works as well as a major section dedicated to Lydian treasures.

Anıtkabir

Anıtkabir is located on an imposing hill, which forms the Anıttepe quarter of the city, where the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Republic of Turkey, stands. Completed in 1953, it is a fusion of ancient and modern architectural styles. An adjacent museum houses a wax statue of Atatürk, his writings, letters and personal items, as well as an exhibition of photographs recording important moments in his life and during the establishment of the Republic. Anıtkabir is open every day, while the adjacent museum is open every day except Mondays.

Ankara Ethnography Museum

Ankara Ethnography Museum (Etnoğrafya Müzesi) is located opposite to the Ankara Opera House on Talat Paşa Boulevard, in the Ulus district. There is a fine collection of folkloric items, as well as artifacts from the Seljuk and Ottoman periods. In front of the museum building, there is a marble and bronze equestrian statue of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (who wears a Republic era modern military uniform, with the rank Field Marshal) which was crafted in 1927[82] by the renowned Italian sculptor Pietro Canonica.

State Art and Sculpture Museum

The State Art and Sculpture Museum (Resim-Heykel Müzesi) which opened to the public in 1980[83] is close to the Ethnography Museum and houses a rich collection of Turkish art from the late 19th century to the present day. There are also galleries which host guest exhibitions.

Cer Modern

Cer Modern is the modern-arts museum of Ankara, inaugurated on 1 April 2010. It is situated in the renovated building of the historic TCDD Cer Atölyeleri, formerly a workshop of the Turkish State Railways. The museum incorporates the largest exhibition hall in Turkey. The museum holds periodic exhibitions of modern and contemporary art as well as hosting other contemporary arts events.

War of Independence Museum

The War of Independence Museum (Kurtuluş Savaşı Müzesi) is located on Ulus Square. It was originally the first Parliament building (TBMM) of the Republic of Turkey. The War of Independence was planned and directed here as recorded in various photographs and items presently on exhibition. In another display, wax figures of former presidents of the Republic of Turkey are on exhibit.

Mehmet Akif Literature Museum Library

The Mehmet Akif Literature Museum Library is an important literary museum and archive opened in 2011 and dedicated to Mehmet Akif Ersoy (1873–1936), the poet of the Turkish National Anthem.

TCDD Open Air Steam Locomotive Museum

The TCDD Open Air Steam Locomotive Museum is an open-air museum which traces the history of steam locomotives.

Ankara Aviation Museum

Ankara Aviation Museum (Hava Kuvvetleri Müzesi Komutanlığı) is located near the Istanbul Road in Etimesgut. The museum opened to the public in September 1998.[84] It is home to various missiles, avionics, aviation materials and aircraft that have served in the Turkish Air Force (e.g. combat aircraft such as the F-86 Sabre, F-100 Super Sabre, F-102 Delta Dagger, F-104 Starfighter, F-5 Freedom Fighter, F-4 Phantom; and cargo planes such as the Transall C-160.) Also a Hungarian MiG-21, a Pakistani MiG-19, and a Bulgarian MiG-17 are on display at the museum.

METU Science and Technology Museum

The METU Science and Technology Museum (ODTÜ Bilim ve Teknoloji Müzesi) is located inside the Middle East Technical University campus.

Sports

As with all other cities of Turkey, football is the most popular sport in Ankara. The city currently has one football club competing in the Turkish Süper Lig: Ankaragücü, founded in 1910, is the oldest club in Ankara and is associated with Ankara's military arsenal manufacturing company MKE. They were the Turkish Cup winners in 1972 and 1981. Gençlerbirliği, founded in 1923, play in the TFF First League and are known as the Ankara Gale or the Poppies because of their colors: red and black. They were the Turkish Cup winners in 1987 and 2001. Ankara Keçiörengücü also currently play in the TFF First League. Büyükşehir Belediye Ankaraspor also played in the Süper Lig until 2010, when they were expelled. The club was reconstituted in 2014 as Osmanlıspor but have since returned to their old identity as Ankaraspor. Ankaraspor currently play in the TFF Second League at the Etimesgut Belediyesi Atatürk Stadium. Gençlerbirliği's B team, Hacettepe S.K. (formerly known as Gençlerbirliği OFTAŞ) played in the Süper Lig but folded in 2023. Ankara Demirspor and Etimesgut Belediyespor also play in the TFF Second League.

Ankara has a large number of minor teams, playing at regional levels, including Çankaya FK, Altındağspor,[85] Mamak FK, Çubukspor, and Bağlumspor.

In the Turkish Basketball Super League, Ankara is represented by Türk Telekom B.K., who play at the Ankara Arena. TED Ankara Kolejliler, MKE Ankaragücü, and OGM Ormanspor play in the second-tier Turkish First League.

Halkbank Ankara is the leading domestic powerhouse in men's volleyball, having won many championships and cups in the Turkish Men's Volleyball League and even the CEV Cup in 2013.

Ankara Buz Pateni Sarayı is where the ice skating and ice hockey competitions take place in the city.

There are many popular spots for skateboarding which is active in the city since the 1980s. Skaters in Ankara usually meet in the park near the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.

The 2012-built THF Sport Hall hosts the Handball Super League and Women's Handball Super League matches scheduled in Ankara.[86]

Parks

Ankara has many parks and open spaces mainly established in the early years of the Republic and well maintained and expanded thereafter. The most important of these parks are: Gençlik Parkı (houses an amusement park with a large pond for rowing), the Botanical garden, Seğmenler Park, Anayasa Park, Kuğulu Park (famous for the swans received as a gift from the Chinese government), Abdi İpekçi Park, Esertepe Parkı, Güven Park (see above for the monument), Kurtuluş Park (has an ice-skating rink), Altınpark (also a prominent exposition/fair area), Harikalar Diyarı (claimed to be Biggest Park of Europe inside city borders) and Göksu Park. Dikmen Vadisi (Dikmen Valley) is a 70 hectares (170 acres) park and recreation area situated in Çankaya district.

Gençlik Park was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 100 lira banknotes of 1952–1976.[87]

Atatürk Forest Farm and Zoo (Atatürk Orman Çiftliği) is an expansive recreational farming area which houses a zoo, several small agricultural farms, greenhouses, restaurants, a dairy farm and a brewery. It is a pleasant place to spend a day with family, be it for having picnics, hiking, biking or simply enjoying good food and nature. There is also an exact replica of the house where Atatürk was born in 1881, in Thessaloniki, Greece. Visitors to the "Çiftlik" (farm) as it is affectionately called by Ankarans, can sample such famous products of the farm such as old-fashioned beer and ice cream, fresh dairy products and meat rolls/kebabs made on charcoal, at a traditional restaurant (Merkez Lokantası, Central Restaurant), cafés and other establishments scattered around the farm.

Education

Universities

Ankara is noted, within Turkey, for the multitude of universities it is home to. These include the following, several of them being among the most reputable in the country:

- Ankara University

- Atılım University

- Başkent University

- Bilkent University

- Çankaya University

- Gazi University

- Gülhane Military Medical Academy

- Hacettepe University

- Middle East Technical University

- TED University

- TOBB University of Economics and Technology

- Turkish Aeronautical Association University

- Turkish Military Academy

- Turkish National Police Academy

- Ufuk University

- Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Fauna

Angora cat

Ankara is home to a world-famous domestic cat breed – the Turkish Angora, called Ankara kedisi (Ankara cat) in Turkish. Turkish Angoras are one of the ancient, naturally occurring cat breeds, having originated in Ankara and its surrounding region in central Anatolia.

They mostly have a white, silky, medium to long length coat, no undercoat and a fine bone structure. There seems to be a connection between the Angora Cats and Persians, and the Turkish Angora is also a distant cousin of the Turkish Van. Although they are known for their shimmery white coat, there are more than twenty varieties including black, blue and reddish fur. They come in tabby and tabby-white, along with smoke varieties, and are in every color other than pointed, lavender, and cinnamon (all of which would indicate breeding to an outcross.)

Eyes may be blue, green, or amber, or even one blue and one amber or green. The W gene which is responsible for the white coat and blue eye is closely related to the hearing ability, and the presence of a blue eye can indicate that the cat is deaf to the side the blue eye is located. However, a great many blue and odd-eyed white cats have normal hearing, and even deaf cats lead a very normal life if kept indoors.

Ears are pointed and large, eyes are almond shaped and the head is massive with a two plane profile. Another characteristic is the tail, which is often kept parallel to the back.

Angora goat

The Angora goat (Turkish: Ankara keçisi) is a breed of domestic goat that originated in Ankara and its surrounding region in central Anatolia.[88]

This breed was first mentioned in the time of Moses, roughly in 1500 BC.[89] The first Angora goats were brought to Europe by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, about 1554, but, like later imports, were not very successful. Angora goats were first introduced in the United States in 1849 by James P. Davis. Seven adult goats were a gift from Sultan Abdülmecid I in appreciation for his services and advice on the raising of cotton.

The fleece taken from an Angora goat is called mohair. A single goat produces between five and eight kilograms (11 and 18 pounds) of hair per year. Angoras are shorn twice a year, unlike sheep, which are shorn only once. Angoras have high nutritional requirements due to their rapid hair growth. A poor quality diet will curtail mohair development. The United States, Turkey, and South Africa are the top producers of mohair.

For a long period of time, Angora goats were bred for their white coat. In 1998, the Colored Angora Goat Breeders Association was set up to promote breeding of colored Angoras. Today, Angora goats produce white, black (deep black to greys and silver), red (the color fades significantly as the goat gets older), and brownish fiber.

Angora goats were depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 50 lira banknotes of 1938–1952.[90]

Angora rabbit

The Angora rabbit (Turkish: Ankara tavşanı) is a variety of domestic rabbit bred for its long, soft hair. The Angora is one of the oldest types of domestic rabbit, originating in Ankara and its surrounding region in central Anatolia, along with the Angora cat and Angora goat. The rabbits were popular pets with French royalty in the mid-18th century, and spread to other parts of Europe by the end of the century. They first appeared in the United States in the early 20th century. They are bred largely for their long Angora wool, which may be removed by shearing, combing, or plucking (gently pulling loose wool).

Angoras are bred mainly for their wool because it is silky and soft. They have a humorous appearance, as they oddly resemble a fur ball. Most are calm and docile but should be handled carefully. Grooming is necessary to prevent the fiber from matting and felting on the rabbit. A condition called "wool block" is common in Angora rabbits and should be treated quickly.[91] Sometimes they are shorn in the summer as the long fur can cause the rabbits to overheat.

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Seoul, South Korea (since 1971)[93][94]

Seoul, South Korea (since 1971)[93][94] Islamabad, Pakistan (since 1982)[95]

Islamabad, Pakistan (since 1982)[95] Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (since 1984)

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (since 1984) Beijing, China (since 1990)[96]

Beijing, China (since 1990)[96] Amman, Jordan (since 1992)

Amman, Jordan (since 1992) Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (since 1992)

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (since 1992) Budapest, Hungary (since 1992)

Budapest, Hungary (since 1992) Khartoum, Sudan (since 1992)

Khartoum, Sudan (since 1992) Moscow, Russia (since 1992)

Moscow, Russia (since 1992) Sofia, Bulgaria (since 1992)

Sofia, Bulgaria (since 1992) Havana, Cuba (since 1993)

Havana, Cuba (since 1993) Kyiv, Ukraine (since 1993)

Kyiv, Ukraine (since 1993) Ashgabat, Turkmenistan (since 1994)

Ashgabat, Turkmenistan (since 1994) Kuwait City, Kuwait (since 1994)

Kuwait City, Kuwait (since 1994) Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 1994)[97]

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 1994)[97] Tirana, Albania (since 1995)[98]

Tirana, Albania (since 1995)[98] Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1996)[99]

Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1996)[99] Ufa, Bashkortostan, Russia (since 1997)

Ufa, Bashkortostan, Russia (since 1997) Alanya, Turkey

Alanya, Turkey Bucharest, Romania (since 1998)

Bucharest, Romania (since 1998) Hanoi, Vietnam (since 1998)

Hanoi, Vietnam (since 1998) Manama, Bahrain (since 2000)

Manama, Bahrain (since 2000) Mogadishu, Somalia (since 2000)

Mogadishu, Somalia (since 2000) Santiago, Chile (since 2000)

Santiago, Chile (since 2000) Astana, Kazakhstan (since 2001)

Astana, Kazakhstan (since 2001) Dushanbe, Tajikistan (since 2003)

Dushanbe, Tajikistan (since 2003) Kabul, Afghanistan (since 2003)

Kabul, Afghanistan (since 2003) Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (since 2003)

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (since 2003) Cairo, Egypt (since 2004)

Cairo, Egypt (since 2004) Chișinău, Moldova (since 2004)[100]

Chișinău, Moldova (since 2004)[100] Sana'a, Yemen (since 2004)

Sana'a, Yemen (since 2004) Tashkent, Uzbekistan (since 2004)

Tashkent, Uzbekistan (since 2004) Pristina, Kosovo (since 2005)

Pristina, Kosovo (since 2005) Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia (since 2005)

Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia (since 2005) Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (since 2005)

Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (since 2005) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (since 2006)

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (since 2006) Minsk, Belarus (since 2007)[101]

Minsk, Belarus (since 2007)[101] Zagreb, Croatia (since 2008)[102]

Zagreb, Croatia (since 2008)[102] Damascus, Syria (since 2010)

Damascus, Syria (since 2010) Bissau, Guinea-Bissau (since 2011)

Bissau, Guinea-Bissau (since 2011) Washington, D.C., US (since 2011)[103]

Washington, D.C., US (since 2011)[103] Bangkok, Thailand (since 2012)[104]

Bangkok, Thailand (since 2012)[104] Tehran, Iran (since 2013)[105]

Tehran, Iran (since 2013)[105] Doha, Qatar (since 2016)[106]

Doha, Qatar (since 2016)[106] Podgorica, Montenegro (since 7 March 2019)

Podgorica, Montenegro (since 7 March 2019) North Nicosia, Northern Cyprus

North Nicosia, Northern Cyprus Djibouti City, Djibouti (since 2017)[107]

Djibouti City, Djibouti (since 2017)[107]

Partner cities

See also

- Angora cat

- Angora goat

- Angora rabbit

- Ankara Agreement

- Ankara Arena

- Ankara Central Station

- Ankara Esenboğa International Airport

- Ankara Metro

- Ankara Province

- Ankara University

- ATO Congresium

- Basil of Ancyra

- Battle of Ancyra

- Battle of Ankara

- Clement of Ancyra

- Gemellus of Ancyra

- History of Ankara

- List of hospitals in Ankara Province

- List of mayors of Ankara

- List of municipalities in Ankara Province

- List of districts of Ankara

- List of people from Ankara

- List of tallest buildings in Ankara

- Marcellus of Ancyra

- Monumentum Ancyranum

- Nilus of Ancyra

- Roman Baths of Ankara

- Synod of Ancyra

- Theodotus of Ancyra (bishop)

- Theodotus of Ancyra (martyr)

- Timeline of Ankara

- Treaty of Ankara (disambiguation)

- Victory Monument (Ankara)

Notes

- ^ İlker, Alan; Zerrin, Demirörs; Rüya, Bayar; Kerime, Karabacak (10 June 2020). "The Case Of Ankara Province (25,653.46 km²)". Ankara University (www.ankara.edu.tr). International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE), 42; pg.650–667.

- ^ "İl ve İlçe Yüz Ölçümleri – Ankara Province (25,632 km²)". www.harita.gov.tr. Harita Genel Müdürlüğü (HGM). 2014.

- ^ a b "Gölbaşı (1,508.61 km²) – Ankara Province (25,575.94 km²) (pg.3)" (PDF). www.csb.gov.tr. T.C. Çevre, Şehircilik ve İklim Değişikliği Bakanlığı. 2020.

- ^ a b c "Ankara City: the population and area of the districts". CityPopulation.de.

- ^ a b "The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2023". www.tuik.gov.tr. Turkish Statistical Institute. 6 February 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ "Nüfus ve Demografi – Toplam Nüfus" (the year is updated). www.tuik.gov.tr. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Ulusal Hesaplar – Kişi başına GSYH ($) [National Accounts – GDP per capita ($)]" (GDP calculated gdp per capita*population). www.tuik.gov.tr. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product by Provinces, 2022 (Tables 1 and 3)". www.tuik.gov.tr. Turkish Statistical Institute. 7 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Ankara". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Ankara". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "Ankara". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Ankara". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Kısaltmalar Dizelgesi".

- ^ "Angora" Archived 30 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine (US) and "Angora". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ Lord Kinross (1965). Ataturk: A Biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Modern Turkey. William Morrow and Company. Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Municipality of Ankara: Green areas per head". Ankara.bel.tr. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Перевод sañkara с санскрита на русский". Словари и энциклопедии на Академике (in Russian). Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Judy Turman: Early Christianity in Turkey". Socialscience.tjc.edu. Archived from the original on 15 November 2002. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Saffet Emre Tonguç: Ankara (Hürriyet Seyahat)". Hurriyet.com.tr. 15 May 2006. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Gorny, Ronald L. "Zippalanda and Ankuwa: The Geography of Central Anatolia in the Second Millennium B.C." The Journal of the American Oriental Society. Vol. 117 (1997).

- ^ a b c Baynes 1878, p. 45.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.4.1., "Ancyra was actually older even than that."

- ^ Livy, xxxviii. 16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Belke, Klaus (1984). "Ankyra". Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 4: Galatien und Lykaonien (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 126–130. ISBN 978-3-7001-0634-0.

- ^ The History of al-Tabari Vol. 33: Storm and Stress along the Northern Frontiers of the 'Abbasid Caliphate: The Caliphate of al-Mu'tasim A.D. 833-842/A.H. 218–227. SUNY Press. 2015. p. 99. ISBN 9780791497210.

- ^ Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- ^ a b c Rockwell 1911.

- ^ Parvis 2006, pp. 325–345.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. p. Chapter 23.

- ^ Bull Universi Dominici gregis Archived 30 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, in Giovanni Domenico Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova et Amplissima Collectio, vol. XL, coll. 779–780

- ^ F. Tournebize, v. II. Ancyre, évêché arménien catholique, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques Archived 28 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, vol. II, Paris 1914, coll. 1543–1546

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 832

- ^ "Ankara | Location, History, Economy, & Facts". Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Society (4 March 2014). "Istanbul, not Constantinople". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Sibel Morrow (19 February 2020). "Turkey's largest library to be disabled-friendly". aa.com.tr. Anadolu Agency.

- ^ Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer

- ^ Deriu, Davide. "A challenge to the West: British views of republican Ankara" (Chapter 12). In: Gharipour, Mohammad and Nilay Özlü (editors). The City in the Muslim World: Depictions by Western Travel Writers. Routledge, 5 March 2015. ISBN 1317548221, 9781317548225. Start: p. 279 Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. CITED: p. 299 Archived 4 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Turkey: Major cities and provinces". City Population. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Nature Scientific Data. DOI:10.1038/sdata.2018.214.

- ^ artunbeg (11 May 2022). "Ankara". Ansiklopedika Viki (in Turkish). Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Genel İstatistik Verileri" (in Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Ankara-Bolge" (CSV). National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original (CSV) on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Population Of SRE-1, SRE-2, Provinces and Districts". TÜIK. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ Gül Neşe Doğusan Alexander (2017). "Caught between Aspiration and Actuality: The Etiler Housing Cooperative and the Production of Housing in Turkey". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 76 (3): 351. doi:10.1525/jsah.2017.76.3.349. JSTOR 26419016.

- ^ "İllere göre il/ilçe merkezi ve belde/köy nüfusu – 2008". report.tuik.gov.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "İllere Göre Türkiye'de 15+ Yaş Nüfusun Eğitim Durumu ve Oranlar (%) | @DrDataStats". based on TÜİK data (in Turkish). Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Chen, Yuan Julian (11 October 2021). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ^ "Emek Business Center, Ankara". Emporis. Emporis. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Işıl Gülkök (September 2013). "New representations of space: Emek office building and Gima Store (in Production of Sidewalks: the Case of Atatürk Boulevard, Ankara)".

- ^ FNSS Savunma Sistemleri A.Ş. "FNSS Savunma Sistemleri A.Ş." Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Nurol Makina ve Sanayi A.Ş." nurolmakina.com.tr. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "MAN Turkiye". man.com.tr. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "EGO Genel Müdürlüğü". Ego.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Largest urban ropeway on Eurasian continent opens to celebrations in Ankara". Leitner ropeways. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ "Successful inauguration of Ankara – Istanbul High Speed Line". uic.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ "Ankara Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Turkish Protester Ethem Sarısülük Is Dead, Family Says [UPDATED]". HuffPost. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Turkey's Prime Minister: Erdoğan v. judges, again". The Economist. Vol. 411, no. 8883. 19 April 2014. pp. 32–36.

- ^ "Turkish opposition party will challenge Ankara vote – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Is Something Rotten in Ankara's Mayoral Election? A Very Preliminary Statistical Analysis". Erik Meyersson. April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Joe Parkinson And Emre Peker (1 April 2014). "Turkish Opposition Cries Vote Fraud Amid Crackdown – WSJ". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ "CHP's Ankara candidate vows to defend votes as police crack down on protest – POLITICS". hurriyetdailynews.com. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Turkey's Weirdest Mayor Won't Be Distracted By Electoral Fraud Allegations". VICE News. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ The citadel was depicted in the following Turkish banknotes:

- On the obverse of the 1 lira banknote of 1927–1939 (1. Emission Group – One Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 17 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the obverse of the 5 lira banknote of 1927–1937 (1. Emission Group – Five Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 10 lira banknote of 1927–1938 (1. Emission Group – Ten Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 10 lira banknote of 1938–1952 (2. Emission Group – Ten Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine).

- On the reverse of the 100 lira banknotes of 1983–1989 (7. Emission Group – One Hundred Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine & II. Series Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Chisholm 1911b, p. 953.

- ^ "Roma Yolu". arkitera.com. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Sargın, Haluk (2012). Antik Ankara (in Turkish). Ankara: Arkadaş Yayınevi. pp. 126, 127, 128. ISBN 978-975-509-719-0.

- ^ "Ahmet Hamdi Akseki Mosque has been opened for prayers". Archived from the original on 18 February 2015.

- ^ SonTech Yazılım. "Hacı Bayram-ı Veli :. hacıbayramveli, hacı bayramveli, haci bayrami veli, hacıbayram, nasihatleri, hacı bayram cami, hayatı, hacıbayram-ı veli". Hacibayramiveli.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Museums – Ankara.com: City guide of Turkey's Capital". Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Ministry of Culture page Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (in Turkish)

- ^ ""Türk Öğün, Çalış, Güven" Sözündeki "Övünmek" Vurgusu". 29 October 2021.

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 15 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Banknotes of 2. Emission Group – Five Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 3 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 15 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Banknote Museum: 2. Emission Group – One Thousand Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine & II. Series Archived 12 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ankara: ESKİ HAN'A YENİ ÇEHRE: SULUHAN". 3 December 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Eski Han'a yeni çehre: Suluhan/Kent Tarihi/milliyet blog". Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Tuncer, Mehmet. "Ankara: ESKİ HAN'A YENİ ÇEHRE: SULUHAN". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Index of /". Boorkestrasi.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Planet, Lonely. "Museum of Anatolian Civilisations – Lonely Planet". Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Ethnography Museum of Ankara – Müze". Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Ankara Art and Sculpture Museum Directorate". Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Turkish Air Force – Air Force Museums – Ankara Aviation Museum". Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Altindağ Spor – Kulüp Bilgileri TFF". tff.org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Hentbol-Şampiyon kim olacak?". Sports TV (in Turkish). 20 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2013.