Histopathology image classification: Highlighting the gap between manual analysis and AI automation

Contents

The radial velocity or line-of-sight velocity of a target with respect to an observer is the rate of change of the vector displacement between the two points. It is formulated as the vector projection of the target-observer relative velocity onto the relative direction or line-of-sight (LOS) connecting the two points.

The radial speed or range rate is the temporal rate of the distance or range between the two points. It is a signed scalar quantity, formulated as the scalar projection of the relative velocity vector onto the LOS direction. Equivalently, radial speed equals the norm of the radial velocity, modulo the sign.[a]

In astronomy, the point is usually taken to be the observer on Earth, so the radial velocity then denotes the speed with which the object moves away from the Earth (or approaches it, for a negative radial velocity).

Formulation

Given a differentiable vector defining the instantaneous relative position of a target with respect to an observer.

Let the instantaneous relative velocity of the target with respect to the observer be

| (1) |

The magnitude of the position vector is defined as in terms of the inner product

| (2) |

The quantity range rate is the time derivative of the magnitude (norm) of , expressed as

| (3) |

Evaluating the derivative of the right-hand-side by the chain rule

using (1) the expression becomes

By reciprocity,[1] . Defining the unit relative position vector (or LOS direction), the range rate is simply expressed as

i.e., the projection of the relative velocity vector onto the LOS direction.

Further defining the velocity direction , with the relative speed , we have:

where the inner product is either +1 or -1, for parallel and antiparallel vectors, respectively.

A singularity exists for coincident observer target, i.e., ; in this case, range rate is undefined.

Applications in astronomy

In astronomy, radial velocity is often measured to the first order of approximation by Doppler spectroscopy. The quantity obtained by this method may be called the barycentric radial-velocity measure or spectroscopic radial velocity.[2] However, due to relativistic and cosmological effects over the great distances that light typically travels to reach the observer from an astronomical object, this measure cannot be accurately transformed to a geometric radial velocity without additional assumptions about the object and the space between it and the observer.[3] By contrast, astrometric radial velocity is determined by astrometric observations (for example, a secular change in the annual parallax).[3][4][5]

Spectroscopic radial velocity

Light from an object with a substantial relative radial velocity at emission will be subject to the Doppler effect, so the frequency of the light decreases for objects that were receding (redshift) and increases for objects that were approaching (blueshift).

The radial velocity of a star or other luminous distant objects can be measured accurately by taking a high-resolution spectrum and comparing the measured wavelengths of known spectral lines to wavelengths from laboratory measurements. A positive radial velocity indicates the distance between the objects is or was increasing; a negative radial velocity indicates the distance between the source and observer is or was decreasing.

William Huggins ventured in 1868 to estimate the radial velocity of Sirius with respect to the Sun, based on observed redshift of the star's light.[6]

In many binary stars, the orbital motion usually causes radial velocity variations of several kilometres per second (km/s). As the spectra of these stars vary due to the Doppler effect, they are called spectroscopic binaries. Radial velocity can be used to estimate the ratio of the masses of the stars, and some orbital elements, such as eccentricity and semimajor axis. The same method has also been used to detect planets around stars, in the way that the movement's measurement determines the planet's orbital period, while the resulting radial-velocity amplitude allows the calculation of the lower bound on a planet's mass using the binary mass function. Radial velocity methods alone may only reveal a lower bound, since a large planet orbiting at a very high angle to the line of sight will perturb its star radially as much as a much smaller planet with an orbital plane on the line of sight. It has been suggested that planets with high eccentricities calculated by this method may in fact be two-planet systems of circular or near-circular resonant orbit.[7][8]

Detection of exoplanets

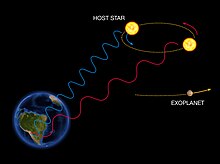

The radial velocity method to detect exoplanets is based on the detection of variations in the velocity of the central star, due to the changing direction of the gravitational pull from an (unseen) exoplanet as it orbits the star. When the star moves towards us, its spectrum is blueshifted, while it is redshifted when it moves away from us. By regularly looking at the spectrum of a star—and so, measuring its velocity—it can be determined if it moves periodically due to the influence of an exoplanet companion.

Data reduction

From the instrumental perspective, velocities are measured relative to the telescope's motion. So an important first step of the data reduction is to remove the contributions of

- the Earth's elliptic motion around the Sun at approximately ± 30 km/s,

- a monthly rotation of ± 13 m/s of the Earth around the center of gravity of the Earth-Moon system,[9]

- the daily rotation of the telescope with the Earth crust around the Earth axis, which is up to ±460 m/s at the equator and proportional to the cosine of the telescope's geographic latitude,

- small contributions from the Earth polar motion at the level of mm/s,

- contributions of 230 km/s from the motion around the Galactic Center and associated proper motions.[10]

- in the case of spectroscopic measurements corrections of the order of ±20 cm/s with respect to aberration.[11]

- Sin i degeneracy is the impact caused by not being in the plane of the motion.

See also

- Proper motion – Measure of observed changes in the apparent locations of stars

- Peculiar velocity – Velocity of an object relative to a rest frame

- Relative velocity – Velocity measured relative to an observer

- Space velocity (astronomy) – Study of the movement of stars

- Bistatic range rate

- Doppler effect

- Inner product

- Orbit determination

- Lp space

Notes

- ^ The norm, a nonnegative number, is multiplied by -1 if velocity (red arrow in the figure) and relative position form an obtuse angle or if relative velocity (green arrow) and relative position are antiparallel.

References

- ^ Hoffman, Kenneth M.; Kunzel, Ray (1971). Linear Algebra (Second ed.). Prentice-Hall Inc. p. 271. ISBN 0135367972.

- ^ Resolution C1 on the Definition of a Spectroscopic "Barycentric Radial-Velocity Measure". Special Issue: Preliminary Program of the XXVth GA in Sydney, July 13–26, 2003 Information Bulletin n° 91. Page 50. IAU Secretariat. July 2002. https://www.iau.org/static/publications/IB91.pdf

- ^ a b Lindegren, Lennart; Dravins, Dainis (April 2003). "The fundamental definition of "radial velocity"" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 401 (3): 1185–1201. arXiv:astro-ph/0302522. Bibcode:2003A&A...401.1185L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030181. S2CID 16012160. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Dravins, Dainis; Lindegren, Lennart; Madsen, Søren (1999). "Astrometric radial velocities. I. Non-spectroscopic methods for measuring stellar radial velocity". Astron. Astrophys. 348: 1040–1051. arXiv:astro-ph/9907145. Bibcode:1999A&A...348.1040D.

- ^ Resolution C 2 on the Definition of "Astrometric Radial Velocity". Special Issue: Preliminary Program of the XXVth GA in Sydney, July 13–26, 2003 Information Bulletin n° 91. Page 51. IAU Secretariat. July 2002. https://www.iau.org/static/publications/IB91.pdf

- ^ Huggins, W. (1868). "Further observations on the spectra of some of the stars and nebulae, with an attempt to determine therefrom whether these bodies are moving towards or from the Earth, also observations on the spectra of the Sun and of Comet II". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 158: 529–564. Bibcode:1868RSPT..158..529H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1868.0022.

- ^ Anglada-Escude, Guillem; Lopez-Morales, Mercedes; Chambers, John E. (2010). "How eccentric orbital solutions can hide planetary systems in 2:1 resonant orbits". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 709 (1): 168–78. arXiv:0809.1275. Bibcode:2010ApJ...709..168A. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/709/1/168. S2CID 2756148.

- ^ Kürster, Martin; Trifonov, Trifon; Reffert, Sabine; Kostogryz, Nadiia M.; Roder, Florian (2015). "Disentangling 2:1 resonant radial velocity oribts from eccentric ones and a case study for HD 27894". Astron. Astrophys. 577: A103. arXiv:1503.07769. Bibcode:2015A&A...577A.103K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525872. S2CID 73533931.

- ^ Ferraz-Mello, S.; Michtchenko, T. A. (2005). "Extrasolar Planetary Systems". Chaos and Stability in Planetary Systems. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 683. pp. 219–271. Bibcode:2005LNP...683..219F. doi:10.1007/10978337_4. ISBN 978-3-540-28208-2.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Reid, M. J.; Dame, T. M. (2016). "On the rotation speed of the Milky Way determined from HI emission". The Astrophysical Journal. 832 (2): 159. arXiv:1608.03886. Bibcode:2016ApJ...832..159R. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/832/2/159. S2CID 119219962.

- ^ Stumpff, P. (1985). "Rigorous treatment of the heliocentric motion of stars". Astron. Astrophys. 144 (1): 232. Bibcode:1985A&A...144..232S.

Further reading

- Hoffman, Kenneth M.; Kunzel, Ray (1971), Linear Algebra (Second ed.), Prentice-Hall Inc., ISBN 0135367972

- Renze, John; Stover, Christopher; and Weisstein, Eric W. "Inner Product." From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.http://mathworld.wolfram.com/InnerProduct.html