Histopathology image classification: Highlighting the gap between manual analysis and AI automation

Contents

A questionnaire is a research instrument that consists of a set of questions (or other types of prompts) for the purpose of gathering information from respondents through survey or statistical study. A research questionnaire is typically a mix of close-ended questions and open-ended questions. Open-ended, long-term questions offer the respondent the ability to elaborate on their thoughts. The Research questionnaire was developed by the Statistical Society of London in 1838.[1][2]

Although questionnaires are often designed for statistical analysis of the responses, this is not always the case.

Questionnaires have advantages over some other types of survey tools in that they are cheap, do not require as much effort from the questioner as verbal or telephone surveys, and often have standardized answers that make it simple to compile data.[3] However, such standardized answers may frustrate users as the possible answers may not accurately represent their desired responses.[4] Questionnaires are also sharply limited by the fact that respondents must be able to read the questions and respond to them. Thus, for some demographic groups conducting a survey by questionnaire may not be concretely feasible.[5]

History

One of the earliest questionnaires was Dean Milles' Questionnaire of 1753.[6]

Types

A distinction can be made between questionnaires with questions that measure separate variables, and questionnaires with questions that are aggregated into either a scale or index. Questionnaires with questions that measure separate variables, could, for instance, include questions on:

- preferences (e.g. political party)

- behaviors (e.g. food consumption)

- facts (e.g. gender)

Questionnaires with questions that are aggregated into either a scale or index include for instance questions that measure:

- latent traits

- attitudes (e.g. towards immigration)

- an index (e.g. Social Economic Status)

Examples

- A food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) is a questionnaire the type of diet consumed in people, and may be used as a research instrument. Examples of usages include assessment of intake of vitamins or toxins such as acrylamide.[7][8]

Questionnaire construction

Question type

Usually, a questionnaire consists of a number of questions (test items) that the respondent has to answer in a set format. A distinction is made between open-ended and closed-ended questions. An open-ended question asks the respondent to formulate his own answer, whereas a closed-ended question asks the respondent to pick an answer from a given number of options. The response options for a closed-ended question should be exhaustive and mutually exclusive. Four types of response scales for closed-ended questions are distinguished:

- Dichotomous, where the respondent has two options. The dichotomous question is generally a "yes/no" close-ended question. This question is usually used in case of the need for necessary validation. It is the most natural form of a questionnaire.

- Nominal-polytomous, where the respondent has more than two unordered options. The nominal scale, also called the categorical variable scale, is defined as a scale used for labeling variables into distinct classifications and does not involve a quantitative value or order.

- Ordinal-polytomous, where the respondent has more than two ordered options

- (Bounded)Continuous, where the respondent is presented with a continuous scale

A respondent's answer to an open-ended question is coded into a response scale afterward. An example of an open-ended question is a question where the testee has to complete a sentence (sentence completion item).[9]

Question sequence

In general, questions should flow logically from one to the next. To achieve the best response rates, questions should flow from the least sensitive to the most sensitive, from the factual and behavioural to the attitudinal, and from the more general to the more specific.[citation needed]

There typically is a flow that should be followed when constructing a questionnaire in regards to the order that the questions are asked. The order is as follows:

- Screens

- Warm-ups

- Transitions

- Skips

- Difficult

- Classification

Screens are used as a screening method to find out early whether or not someone should complete the questionnaire. Warm-ups are simple to answer, help capture interest in the survey, and may not even pertain to research objectives. Transition questions are used to make different areas flow well together. Skips include questions similar to "If yes, then answer question 3. If no, then continue to question 5." Difficult questions are towards the end because the respondent is in "response mode." Also, when completing an online questionnaire, the progress bars lets the respondent know that they are almost done so they are more willing to answer more difficult questions. Classification, or demographic question should be at the end because typically they can feel like personal questions which will make respondents uncomfortable and not willing to finish survey.[10]

Basic rules for questionnaire item construction

- Use statements that are interpreted in the same way by members of different subpopulations of the population of interest.

- Use statements where persons that have different opinions or traits will give different answers.

- Think of having an "open" answer category after a list of possible answers.

- Use only one aspect of the construct you are interested in per item.

- Use positive statements and avoid negatives or double negatives.

- Do not make assumptions about the respondent.

- Use clear and comprehensible wording, easily understandable for all educational levels

- Use correct spelling, grammar and punctuation.

- Avoid items that contain more than one question per item (e.g. Do you like strawberries and potatoes?).

- Question should not be biased or even leading the participant towards an answer.

- Incorporate research questions like MaxDiff and Conjoint to help collect actionable data.[11]

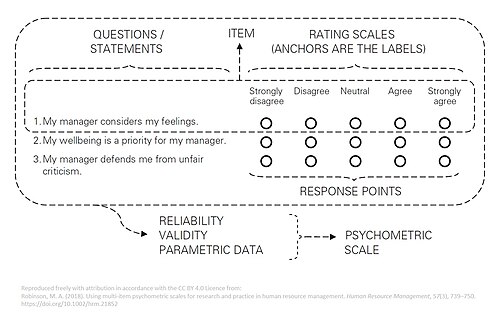

Multi-item scales

Within social science research and practice, questionnaires are most frequently used to collect quantitative data using multi-item scales with the following characteristics:[12]

- Multiple statements or questions (minimum ≥3; usually ≥5) are presented for each variable being examined.

- Each statement or question has an accompanying set of equidistant response-points (usually 5–7).

- Each response point has an accompanying verbal anchor (e.g., "strongly agree") ascending from left to right.

- Verbal anchors should be balanced to reflect equal intervals between response-points.

- Collectively, a set of response-points and accompanying verbal anchors are referred to as a rating scale. One very frequently-used rating scale is a Likert scale.

- Usually, for clarity and efficiency, a single set of anchors is presented for multiple rating scales in a questionnaire.

- Collectively, a statement or question with an accompanying rating scale is referred to as an item.

- When multiple items measure the same variable in a reliable and valid way, they are collectively referred to as a multi-item scale, or a psychometric scale.

- The following types of reliability and validity should be established for a multi-item scale: internal reliability, test-retest reliability (if the variable is expected to be stable over time), content validity, construct validity, and criterion validity.

- Factor analysis is used in the scale development process.

- Questionnaires used to collect quantitative data usually comprise several multi-item scales, together with an introductory and concluding section.

Questionnaire administration modes

Main modes of questionnaire administration include:[9]

- Face-to-face questionnaire administration, where an interviewer presents the items orally.

- Paper-and-pencil questionnaire administration, where the items are presented on paper.

- Computerized questionnaire administration, where the items are presented on the computer.

- Adaptive computerized questionnaire administration, where a selection of items is presented on the computer, and based on the answers on those items, the computer selects the following items optimized for the testee's estimated ability or trait.

Questionnaire translation

Questionnaires are translated from a source language into one or more target languages, such as translating from English into Spanish and German. The process is not a mechanical word placement process. Best practice includes parallel translation, team discussions, and pretesting with real-life people,[13][14] and is integrated in the model TRAPD (Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pretest, and Documentation).[15] A theoretical framework is also provided by sociolinguistics, which states that to achieve the equivalent communicative effect as the source language, the translation must be linguistically appropriate while incorporating the social practices and cultural norms of the target language.[16]

Besides translators, a team approach is recommended in the questionnaire translation process to include subject-matter experts and persons helpful to the process.[15][17] For example, even when project managers and researchers do not speak the language of the translation, they know the study objectives well and the intent behind the questions, and therefore have a key role in improving questionnaire translation.[18]

Concerns with questionnaires

While questionnaires are inexpensive, quick, and easy to analyze, often the questionnaire can have more problems than benefits. For example, unlike interviews, the people conducting the research may never know if the respondent understood the question that was being asked. Also, because the questions are so specific to what the researchers are asking, the information gained can be minimal.[19] Often, questionnaires such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, give too few options to answer; respondents can answer either option but must choose only one response. Questionnaires also produce very low return rates, whether they are mail or online questionnaires. The other problem associated with return rates is that often the people who do return the questionnaire are those who have a very positive or a very negative viewpoint and want their opinion heard. The people who are most likely unbiased either way typically do not respond because it is not worth their time.

One key concern with questionnaires is that they may contain quite large measurement errors.[20] These errors can be random or systematic. Random errors are caused by unintended mistakes by respondents, interviewers, and/or coders. Systematic error can occur if there is a systematic reaction of the respondents to the scale used to formulate the survey question. Thus, the exact formulation of a survey question and its scale is crucial, since they affect the level of measurement error.[21]

Further, if the questionnaires are not collected using sound sampling techniques, often the results can be non-representative of the population—as such a good sample is critical to getting representative results based on questionnaires.[22]

See also

- Survey methodology

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Computer-assisted personal interviewing

- Enterprise Feedback Management

- Quantitative marketing research

- Questionnaire construction

- Structured interviewing

- Web-based experiments

- Position analysis questionnaire

- Abnormal construction

Further reading

- Foddy, W. H. (1994). Constructing questions for interviews and questionnaires: Theory and practice in social research (New ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gillham, B. (2008). Developing a questionnaire (2nd ed.). London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

- Leung, W. C. (2001). "How to conduct a survey". Student BMJ. 9: 143–5.

- Mellenbergh, G. J. (2008). Chapter 10: Tests and questionnaires: Construction and administration. In H. J. Adèr & G. J. Mellenbergh (Eds.) (with contributions by D. J. Hand), Advising on research methods: A consultant's companion (pp. 211–234). Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing.

- Mellenbergh, G. J. (2008). Chapter 11: Tests and questionnaires: Analysis. In H. J. Adèr & G. J. Mellenbergh (Eds.) (with contributions by D. J. Hand), Advising on research methods: A consultant's companion (pp. 235–268). Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing.

- Munn, P., & Drever, E. (2004). Using questionnaires in small-scale research: A beginner's guide. Glasgow, Scotland: Scottish Council for Research in Education.

- Oppenheim, A. N. (2000). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement (New ed.). London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

- Robinson, M. A. (2018). Using multi-item psychometric scales for research and practice in human resource management. Human Resource Management, 57(3), 739–750. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21852 (open-access)

Questionnaire are of different types as per Paul: 1)Structured Questionnaire. 2)Unstructured Questionnaire. 3)Open ended Questionnaire. 4)Close ended Questionnaire. 5)Mixed Questionnaire. 6)Pictorial Questionnaire.

References

- ^ Gault, RH (1907). "A history of the questionnaire method of research in psychology". Research in Psychology. 14 (3): 366–383. doi:10.1080/08919402.1907.10532551.

- ^ A copy of the instrument was published in the Journal of the Statistical Society, Volume 1, Issue 1, 1838, pages 5–13. Fourth Annual Report of the Council of the Statistical Society of London, JSTOR i315562

- ^ "The Roma have a much younger population". OECD Economic Surveys: Slovak Republic. 2019-02-05. doi:10.1787/d8c7c39a-en. ISBN 9789264311350. ISSN 1999-0588. S2CID 242796295.

- ^ "questions-answers-the-international-criminal-court-may-2010". doi:10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-0162-0046.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rajaee Rizi, Farid; Asgarian, Fatemeh Sadat (2022-08-24). "Reliability, validity, and psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Tayside children's sleep questionnaire" (PDF). Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 21: 97–103. doi:10.1007/s41105-022-00420-6. ISSN 1479-8425. S2CID 245863909.

- ^ Fox, Adam, Parochial Queries: Printed Questionnaires and the Pursuit of Natural:Knowledge in the British Isles, 1650–1800, Edinburgh University

- ^ Smedts HP, de Vries JH, Rakhshandehroo M, et al. (February 2009). "High maternal vitamin E intake by diet or supplements is associated with congenital heart defects in the offspring". BJOG. 116 (3): 416–23. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01957.x. PMID 19187374. S2CID 22276050.

- ^ Hogervorst, J. G.; Schouten, L. J.; Konings, E. J.; Goldbohm, R. A.; Van Den Brandt, P. A. (2007). "A Prospective Study of Dietary Acrylamide Intake and the Risk of Endometrial, Ovarian, and Breast Cancer" (PDF). Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (11): 2304–2313. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0581. PMID 18006919. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ a b Mellenbergh, G.J. (2008). Chapter 10: Tests and Questionnaires: Construction and administration. In H.J. Adèr & G.J. Mellenbergh (Eds.) (with contributions by D.J. Hand), Advising on Research Methods: A consultant's companion (pp. 211–236). Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing.

- ^ Burns, A. C., & Bush, R. F. (2010). Marketing Research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- ^ "How to Make Questionnaire". SurveyKing. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ a b Robinson, M. A. (2018). Using multi-item psychometric scales for research and practice in human resource management. Human Resource Management, 57(3), 739–750. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21852 (open-access)

- ^ "Special Issue on Questionnaire Translation". World Association for Public Opinion Research. 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- ^ Behr, Dorothée; Sha, Mandy (2018-07-25). "Introduction: Translation of questionnaires in cross-national and cross-cultural research". Translation & Interpreting. 10 (2): 1–4. doi:10.12807/ti.110202.2018.a01. ISSN 1836-9324.

- ^ a b Harkness, Janet (2003). Cross-cultural survey methods. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-38526-3.

- ^ Pan, Yuling; Sha, Mandy (2019-07-09). The Sociolinguistics of Survey Translation. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429294914. ISBN 978-0-429-29491-4. S2CID 198632812.

- ^ Behr, Dorothe; Shishido, Kuniaki (2016). The Translation of Measurement Instruments for Cross-Cultural Surveys (Chapter 19) in The SAGE Handbook of Survey Methodology. SAGE Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4739-5789-3.

- ^ Sha, Mandy; Immerwahr, Stephen (2018-02-19). "Survey Translation: Why and How Should Researchers and Managers be Engaged?". Survey Practice. 11 (2): 1–10. doi:10.29115/SP-2018-0016. S2CID 155857898.

- ^ Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2009). Psychological testing: Principles, applications, and issues. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth

- ^ Alwin, D. F. (2007). Margins of error: A study of reliability in survey measurement. Hoboken, Wiley

- ^ Saris, W. E. and Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. Second Edition. Hoboken, Wiley.

- ^ Moser, Claus Adolf, and Graham Kalton. "Survey methods in social investigation." Survey methods in social investigation. 2nd Edition (1971).

External links

- Harmonised questions from the UK Office for National Statistics

- Hints for designing effective questionnaires - from the ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation