Histopathology image classification: Highlighting the gap between manual analysis and AI automation

Contents

The Moon bears substantial natural resources which could be exploited in the future.[1][2] Potential lunar resources may encompass processable materials such as volatiles and minerals, along with geologic structures such as lava tubes that, together, might enable lunar habitation. The use of resources on the Moon may provide a means of reducing the cost and risk of lunar exploration and beyond.[3][4]

Insights about lunar resources gained from orbit and sample-return missions have greatly enhanced the understanding of the potential for in situ resource utilization (ISRU) at the Moon, but that knowledge is not yet sufficient to fully justify the commitment of large financial resources to implement an ISRU-based campaign.[5] The determination of resource availability will drive the selection of sites for human settlement.[6][7]

Overview

Lunar materials could facilitate continued exploration of the Moon, facilitate scientific and economic activity in the vicinity of both Earth and Moon (so-called cislunar space), or they could be imported to the Earth's surface where they would contribute directly to the global economy.[1] Regolith (lunar soil) is the easiest product to obtain; it can provide radiation and micrometeoroid protection as well as construction and paving material by melting.[8] Oxygen from lunar regolith oxides can be a source for metabolic oxygen and rocket propellant oxidizer. Water ice can provide water for radiation shielding, life-support, oxygen and rocket propellant feedstock. Volatiles from permanently shadowed craters may provide methane (CH

4), ammonia (NH

3), carbon dioxide (CO

2) and carbon monoxide (CO).[9] Metals and other elements for local industry may be obtained from the various minerals found in regolith.

The Moon is known to be poor in carbon and nitrogen, and rich in metals and in atomic oxygen, but their distribution and concentrations are still unknown. Further lunar exploration will reveal additional concentrations of economically useful materials, and whether or not these will be economically exploitable will depend on the value placed on them and on the energy and infrastructure available to support their extraction.[10] For in situ resource utilization (ISRU) to be applied successfully on the Moon, landing site selection is imperative, as well as identifying suitable surface operations and technologies.

Scouting from lunar orbit by a few space agencies is ongoing, and landers and rovers are scouting resources and concentrations in situ (see: List of missions to the Moon).

Resources

| Compound | Formula | Composition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maria | Highlands | ||

| silica | SiO2 | 45.4% | 45.5% |

| alumina | Al2O3 | 14.9% | 24.0% |

| lime | CaO | 11.8% | 15.9% |

| iron(II) oxide | FeO | 14.1% | 5.9% |

| magnesia | MgO | 9.2% | 7.5% |

| titanium dioxide | TiO2 | 3.9% | 0.6% |

| sodium oxide | Na2O | 0.6% | 0.61% |

| 99.9% | 100.0% | ||

Solar power, oxygen, and metals are abundant resources on the Moon.[12] Elements known to be present on the lunar surface include, among others, hydrogen (H),[1][13] oxygen (O), silicon (Si), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), aluminium (Al), manganese (Mn) and titanium (Ti). Among the more abundant are oxygen, iron and silicon. The atomic oxygen content in the regolith is estimated at 45% by weight.[14][15]

Studies from Apollo 17's Lunar Atmospheric Composition Experiment (LACE) show that the lunar exosphere contains trace amounts of hydrogen (H2), helium (He), argon (Ar), and possibly ammonia (NH3), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4). Several processes can explain the presence of trace gases on the Moon: high energy photons or solar winds reacting with materials on the lunar surface, evaporation of lunar regolith, material deposits from comets and meteoroids, and out-gassing from inside the Moon. However, these are trace gases in very low concentration.[16] The total mass of the Moon's exosphere is roughly 25,000 kilograms (55,000 lb) with a surface pressure of 3×10−15 bar (2×10−12 torr).[17] Trace gas amounts are unlikely to be useful for in situ resource utilization.

Solar power

Daylight on the Moon lasts approximately two weeks, followed by approximately two weeks of night, while both lunar poles are illuminated almost constantly.[18][19][20] The lunar south pole features a region with crater rims exposed to near constant solar illumination, yet the interior of the craters are permanently shaded from sunlight.

Solar cells could be fabricated directly on the lunar soil by a medium-size (~200 kg) rover with the capabilities for heating the regolith, evaporation of the appropriate semiconductor materials for the solar cell structure directly on the regolith substrate, and deposition of metallic contacts and interconnects to finish off a complete solar cell array directly on the ground.[21] This process however requires the importation of potassium fluoride from Earth to purify the necessary materials from regolith.[22]

Nuclear power

The Kilopower nuclear fission system is being developed for reliable electric power generation that could enable long-duration crewed bases on the Moon, Mars and destinations beyond.[23][24] This system is ideal for locations on the Moon and Mars where power generation from sunlight is intermittent.[24][25] Uranium and thorium are both present on the Moon, but due to the high energy density of nuclear fuels, it could be more economical to import suitable fuels from Earth rather than producing them in situ.

Radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) are another form of nuclear power which use the natural decay of radioisotopes rather than their induced fission. They have been used in space—including on the Moon—for decades. The usual process is to source the suitable substances from Earth, but plutonium-238 or strontium-90 could be produced on the Moon if feedstocks such as spent nuclear fuel are present (either delivered from Earth for processing or produced by local fission reactors). RTGs could be used to deliver power independent of available sunlight, for both lunar and non-lunar applications. RTGs do contain harmful toxic and radioactive materials, which leads to concerns of unintentional distribution of those materials in the event of an accident. Protests by the general public therefore often focus on the phaseout of RTGs (instead recommending alternative power sources), due to an overestimation of the dangers of radiation.

A more theoretical lunar resource are potential fuels for nuclear fusion. Helium-3 has received particular media attention as its abundance in lunar regolith is higher than on Earth. However, thus far nuclear fusion has not been employed by humans in a controlled fashion releasing net usable energy (devices like the fusor are net energy consumers while the hydrogen bomb is not a controlled fusion reaction). Furthermore, while helium-3 is required for one possible pathway of nuclear fusion, others instead rely on nuclides which are more easily obtained on Earth, such as tritium, lithium or deuterium.

Oxygen

The elemental oxygen content in the regolith is estimated at 45% by weight.[15][14] Oxygen is often found in iron-rich lunar minerals and glasses as iron oxide. Such lunar minerals and glass include ilmenite, olivine, pyroxene, impact glass, and volcanic glass.[26] Various isotopes of oxygen are present on the Moon in the form of 16O, 17O, and 18O.[27]

At least twenty different possible processes for extracting oxygen from lunar regolith have been described,[28][29] and all require high energy input: between 2–4 megawatt-years of energy (i.e. (6–12)×1013 J) to produce 1,000 tons of oxygen.[1] While oxygen extraction from metal oxides also produces useful metals, using water as a feedstock does not.[1] One possible method of producing oxygen from lunar soil requires two steps. The first step involves the reduction of iron oxide with hydrogen gas (H2) to form elemental iron (Fe) and water (H2O).[26] Water can then be electrolyzed to produce oxygen which can be liquified at low temperatures and stored. The amount of oxygen released depends on the iron oxide abundance in lunar minerals and glass. Oxygen production from lunar soil is a relatively fast process, occurring in a few tens of minutes. In contrast, oxygen extraction from lunar glass requires several hours.[26]

Water

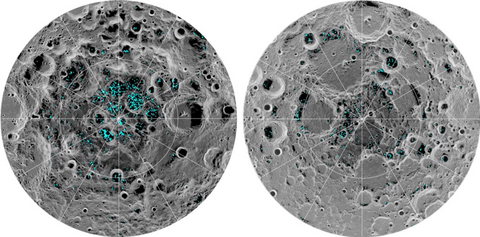

Cumulative evidence from several orbiters strongly indicate that water ice is present on the surface at the Moon poles, but mostly on the south pole region.[30][31] However, results from these datasets are not always correlated.[32][33] It has been determined that the cumulative area of permanently shadowed lunar surface is 13,361 km2 in the northern hemisphere and 17,698 km2 in the southern hemisphere, giving a total area of 31,059 km2.[1] The extent to which any or all of these permanently shadowed areas contain water ice and other volatiles is not currently known, so more data is needed about lunar ice deposits, its distribution, concentration, quantity, disposition, depth, geotechnical properties and any other characteristics necessary to design and develop extraction and processing systems.[33][34] The intentional impact of the LCROSS orbiter into the crater Cabeus was monitored to analyze the resulting debris plume, and it was concluded that the water ice must be in the form of small (< ~10 cm), discrete pieces of ice distributed throughout the regolith, or as a thin coating on ice grains.[35] This, coupled with monostatic radar observations, suggest that the water ice present in the permanently shadowed regions of lunar polar craters is unlikely to be present in the form of thick, pure ice deposits.[35]

Water may have been delivered to the Moon over geological timescales by the regular bombardment of water-bearing comets, asteroids and meteoroids[36] or continuously produced in situ by the hydrogen ions (protons) of the solar wind impacting oxygen-bearing minerals.[1][37]

The lunar south pole features a region with crater rims exposed to near constant solar illumination, where the craters' interior are permanently shaded from sunlight, allowing for natural trapping and collection of water ice that could be mined in the future.

Water molecules (H

2O) can be broken down to form molecular hydrogen (H

2) and molecular oxygen (O

2) to be used as rocket bi-propellant or produce compounds for metallurgic and chemical production processes.[3] Just the production of propellant, was estimated by a joint panel of industry, government and academic experts, identified a near-term annual demand of 450 metric tons of lunar-derived propellant equating to 2,450 metric tons of processed lunar water, generating US$2.4 billion of revenue annually.[25]

Hydrogen

Slopes on the lunar surface that face the Moon's poles show a higher concentration of hydrogen. This is because pole facing slopes have less exposure to sunlight that will cause vaporization of hydrogen. Additionally, slopes closer to the Moon's poles show a higher concentration of hydrogen of about 45 ppmw. There are various theories to explain the presence of hydrogen on the Moon. Water, which contains hydrogen, could have been deposited on the Moon by comets and asteroids. Additionally, solar winds interacting with compounds on the lunar surface may have led to the formation of hydrogen-bearing compounds such as hydroxyl and water.[38] The solar wind implants protons on the regolith, forming a protonated atom, which is a chemical compound of hydrogen (H). Although bound hydrogen is plentiful, questions remain about how much of it diffuses into the subsurface, escapes into space or diffuses into cold traps.[39] Hydrogen would be needed for propellant production, and it has a multitude of industrial uses. For example, hydrogen can be used for the production of oxygen by hydrogen reduction of ilmenite.[40][41][42]

Metals

Iron

| Mineral | Elements | Lunar rock appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Plagioclase feldspar | Calcium (Ca) Aluminium (Al) Silicon (Si) Oxygen (O) |

White to transparent gray; usually as elongated grains. |

| Pyroxene | Iron (Fe), Magnesium (Mg) Calcium (Ca) Silicon (Si) Oxygen (O) |

Maroon to black; the grains appear more elongated in the maria and more square in the highlands. |

| Olivine | Iron (Fe) Magnesium (Mg) Silicon (Si) Oxygen (O) |

Greenish color; generally, it appears in a rounded shape. |

| Ilmenite | Iron (Fe), Titanium (Ti) Oxygen (O) |

Black, elongated square crystals. |

Iron (Fe) is abundant in all mare basalts (~14–17% per weight) but is mostly locked into silicate minerals (i.e. pyroxene and olivine) and into the oxide mineral ilmenite in the lowlands.[1][44] Extraction would be quite energy-demanding, but some prominent lunar magnetic anomalies are suspected as being due to surviving Fe-rich meteoritic debris. Only further exploration in situ will determine whether or not this interpretation is correct, and how exploitable such meteoritic debris may be.[1] Hematite, a mineral composed of ferric oxide (Fe2O3), has been found on the Moon. This mineral is a product of a reaction between iron, oxygen, and liquid water. Oxygen from the Earth's atmosphere may cause this reaction as indicated by there being more hematite on the side of the Moon facing the Earth.[45]

Free iron also exists in the regolith (0.5% by weight) naturally alloyed with nickel and cobalt and it can easily be extracted by simple magnets after grinding.[44] This iron dust can be processed to make parts using powder metallurgy techniques,[44] such as additive manufacturing, 3D printing, selective laser sintering (SLS), selective laser melting (SLM), and electron beam melting (EBM).

Titanium

Titanium (Ti) can be alloyed with iron, aluminium, vanadium, and molybdenum, among other elements, to produce strong, lightweight alloys for aerospace use. It exists almost exclusively in the mineral ilmenite (FeTiO3) in the range of 5–8% by weight.[1] Ilmenite minerals also trap hydrogen (protons) from the solar wind, so that processing of ilmenite will also produce hydrogen, a valuable element on the Moon.[44] The vast flood basalts on the northwest nearside (Mare Tranquillitatis) possess some of the highest titanium contents on the Moon,[33] with 10 times as much titanium as rocks on Earth.[46]

Aluminum

Aluminum (Al) is found with a concentration in the range of 10–18% by weight, present in the mineral anorthite (CaAl

2Si

2O

8),[44] the calcium endmember of the plagioclase feldspar mineral series.[1] Aluminum is a good electrical conductor, and atomized aluminum powder also makes a good solid rocket fuel when burned with oxygen.[44] Extraction of aluminum would also require breaking down plagioclase (CaAl2Si2O8).[1]

Silicon

Silicon (Si) is an abundant metalloid in all lunar material, with a concentration of about 20% by weight. It is of enormous importance to produce solar panel arrays for the conversion of sunlight into electricity, as well as glass, fiber glass, and a variety of useful ceramics. Achieving a very high purity for use as semi-conductor would be challenging, especially in the lunar environment.[1] Converting silica into silicon is an energy-intensive process. On earth this is usually done via carbothermic reduction, a process that requires carbon, an element in comparatively short supply on the moon.

Calcium

Calcium (Ca) is the fourth most abundant element in the lunar highlands, present in anorthite minerals (formula CaAl

2Si

2O

8).[44][47] Calcium oxides and calcium silicates are not only useful for ceramics, but pure calcium metal is flexible and an excellent electrical conductor in the absence of oxygen.[44] Anorthite is rare on the Earth[48] but abundant on the Moon.[44]

Calcium can also be used to fabricate silicon-based solar cells, requiring lunar silicon, iron, titanium oxide, calcium and aluminum.[49]

When combined with water, lime (calcium oxide) produces significant amounts of heat. hydrated lime (calcium hydroxide) meanwhile absorbs carbon dioxide which can be used as a (non-replenishing) filter. The resulting material, calcium carbonate is commonly used as a building material on earth.

Magnesium

Magnesium (Mg) is present in magmas and in the lunar minerals pyroxene and olivine,[50] so it is suspected that magnesium is more abundant in the lower lunar crust.[51] Magnesium has multiple uses as alloys for aerospace, automotive and electronics.

Thorium

The Compton–Belkovich Thorium Anomaly is a volcanic complex on the far side of the Moon.[52] It was found by a gamma-ray spectrometer in 1998 and is an area of concentrated thorium, a 'fertile' element.[52][53]

Rare-earth elements

Rare-earth elements are used to manufacture everything from electric or hybrid vehicles, wind turbines, electronic devices and clean energy technologies.[54][55] Despite their name, rare-earth elements are – with the exception of promethium – relatively plentiful in Earth's crust. However, because of their geochemical properties, rare-earth elements are typically dispersed and not often found concentrated in rare-earth minerals; as a result, economically exploitable ore deposits are less common.[56] Major reserves exist in China, California, India, Brazil, Australia, South Africa, and Malaysia,[57] but China accounts for over 95% of the world's production of rare-earths.[58] (See: Rare earth industry in China.)

Although current evidence suggests rare-earth elements are less abundant on the Moon than on Earth,[59] NASA views the mining of rare-earth minerals as a viable lunar resource[60] because they exhibit a wide range of industrially important optical, electrical, magnetic and catalytic properties.[1] KREEP are parts of the lunar surface richer in potassium (the "K" stands for the element symbol) rare earth elements and Phosphorus. Potassium and phosphorus are two of the three essential plant nutrients, the third being fixed nitrogen (hence NPK fertilizer) any agricultural activity on the moon would need a supply of those elements — whether sourced in situ or brought from elsewhere e.g. earth.

Helium-3

By one estimate, the solar wind has deposited more than 1 million tons of helium-3 (3He) on the Moon's surface.[61] Materials on the Moon's surface contain helium-3 at concentrations estimated between 1.4 and 15 parts per billion (ppb) in sunlit areas,[1][62][63] and may contain concentrations as much as 50 ppb in permanently shadowed regions.[64] For comparison, helium-3 in the Earth's atmosphere occurs at 7.2 parts per trillion (ppt).

A number of people since 1986[65] have proposed to exploit the lunar regolith and use the helium-3 for nuclear fusion.[60] Although as of 2020, functioning experimental nuclear fusion reactors have existed for decades[66][67] – none of them has yet provided electricity commercially.[68][69] Because of the low concentrations of helium-3, any mining equipment would need to process large amounts of regolith. By one estimate, over 150 tons of regolith must be processed to obtain 1 gram (0.035 oz) of helium 3.[70] China has begun the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program for exploring the Moon and is investigating the prospect of lunar mining, specifically looking for the isotope helium-3 for use as an energy source on Earth.[71] Not all authors think the extraterrestrial extraction of helium-3 is feasible,[68] and even if it was possible to extract helium-3 from the Moon, no useful fusion reactor design has produced more fusion power output than the electrical power input, defeating the purpose.[68][69] However, on 13 December 2022, the United States Department of Energy announced that "...Monday, December 5, 2022, was a historic day in science thanks to the incredible people at Livermore Lab and the National Ignition Facility" and that the National Ignition Facility, "conducted the first controlled fusion experiment in history to reach this milestone, also known as scientific energy breakeven, meaning it produced more energy from fusion than the laser energy used to drive it."[72] The downside remains that Helium-3 is a limited lunar resource that can be exhausted once mined.[10]

Carbon and nitrogen

Carbon (C) would be required for the production of lunar steel, but it is present in lunar regolith in trace amounts (82 ppm[73]), contributed by the solar wind and micrometeorite impacts.[74] Due to extremely low temperatures, permanently shadowed regions of the Moon's poles have cold traps which possibly contain solid carbon dioxide.[75] The presence of carbon is mostly due to solar wind carbon implanted in bulk regolith. Carbon is present in carbon-bearing ices at the lunar poles in concentrations as high as 20% by weight. However, most carbon-bearing ices have a 0–3% by weight carbon concentration. Carbon-bearing compounds that could exist include carbon monoxide (CO), ethylene (C2H4), carbon dioxide (CO2), methanol (CH3OH), methane (CH4), carbonyl sulfide (OCS), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and toluene (C7H8). These compounds form roughly 5000 ppm of elemental carbon in soil samples brought back from the Moon. These polar regions contain C, H, and O which can serve as propellant sources for methalox spacecraft.[76]

Nitrogen (N) was measured from soil samples brought back to Earth, and it exists as trace amounts at less than 5 ppm.[77] It was found as isotopes 14N, 15N, and 16N.[77][78] As much as 87% of nitrogen found in lunar regolith may come from non-solar sources (not from the Sun) or from other planets. Comets and meteorites contribute less than ~10% of nitrogen from non-solar sources.[79] Carbon and fixed nitrogen would be required for farming activities within a sealed biosphere.

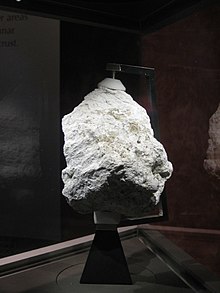

Changesite–(Y)

Regolith for construction

Developing a lunar economy will require a significant amount of infrastructure on the lunar surface, which will rely heavily on In situ resource utilization (ISRU) technologies to develop. One of the primary requirements will be to provide construction materials to build habitats, storage bins, landing pads, roads and other infrastructure.[80][81] Unprocessed lunar soil, also called regolith, may be turned into usable structural components,[82][83] through techniques such as sintering, hot-pressing, liquification, the cast basalt method,[20][84] and 3D printing.[80] Glass and glass fiber are straightforward to process on the Moon, and it was found regolith material strengths can be improved by using glass fiber, such as 70% basalt glass fiber and 30% PETG mixture.[80] Successful tests have been performed on Earth using some lunar regolith simulants,[85] including MLS-1 and MLS-2.[86]

The lunar soil, although it poses a problem for any mechanical moving parts, can be mixed with carbon nanotubes and epoxies in the construction of telescope mirrors up to 50 meters in diameter.[87][88][89] Several craters near the poles are permanently dark and cold, a favorable environment for infrared telescopes.[90]

Some proposals suggest to build a lunar base on the surface using modules brought from Earth, and covering them with lunar soil. The lunar soil is composed of a blend of silica and iron-containing compounds that may be fused into a glass-like solid using microwave radiation.[91][92]

The European Space Agency working in 2013 with an independent architectural firm, tested a 3D-printed structure that could be constructed of lunar regolith for use as a Moon base.[93][94][95] 3D-printed lunar soil would provide both "radiation and temperature insulation. Inside, a lightweight pressurized inflatable with the same dome shape would be the living environment for the first human Moon settlers."[95]

In early 2014, NASA funded a small study at the University of Southern California to further develop the Contour Crafting 3D printing technique. Potential applications of this technology include constructing lunar structures of a material that could consist of up to 90-percent lunar material with only ten percent of the material requiring transport from Earth.[96] NASA is also looking at a different technique that would involve the sintering of lunar dust using low-power (1500 watt) microwave radiation. The lunar material would be bound by heating to 1,200 to 1,500 °C (2,190 to 2,730 °F), somewhat below the melting point, in order to fuse the nanoparticle dust into a solid block that is ceramic-like, and would not require the transport of a binder material from Earth.[97]

Mining

There are several models and proposals on how to exploit lunar resources, yet few of them consider sustainability.[98] Long-term planning is required to achieve sustainability and ensure that future generations are not faced with a barren lunar wasteland by wanton practices.[98][99][100] To be truly sustainable, lunar mining would have to adopt processes that do not use nor yield toxic material, and would minimize waste through recycling loops.[98][81]

Scouting

Numerous orbiters have mapped the lunar surface composition, including Clementine, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), Artemis orbiter, SELENE, Lunar Prospector, Chandrayaan, and Chang'e, to name a few, while the Soviet Luna programme and Apollo Program brought lunar samples back to Earth for extensive analyses. As of 2019, a new "Moon race" is ongoing that features prospecting for lunar resources to support crewed bases.

In the 21st century, China's Chinese Lunar Exploration Program,[101][102] is executing a step-wise approach to incremental technology development and scouting for resources for a crewed base, projected for the 2030s, according to Chinese state media Xinhua News Agency.[103] India's Chandrayaan programme is focused in understanding the lunar water cycle first, and on mapping mineral location and concentrations from orbit and in situ. Russia's Luna-Glob programme is planning and developing a series of landers, rovers and orbiters for prospecting and science exploration, and to eventually employ in situ resource utilization (ISRU) methods with the intent to construct and operate their own crewed lunar base in the 2030s.[104][105]

The US has been studying the Moon for decades and in 2019 it started to implement the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program to support the crewed Artemis program, both aimed at scouting and exploiting lunar resources to facilitate a long-term crewed base on the Moon, and depending on the lessons learned, then move on to a crewed mission to Mars.[106] NASA's lunar Resource Prospector rover was planned to prospect for resources on a polar region of the Moon, and it was to be launched in 2022.[107][108] The mission concept was in its pre-formulation stage, and a prototype rover was being tested when it was cancelled in April 2018.[109][107][108] Its science instruments will be flown instead on several commercial lander missions contracted by NASA's CLPS program, that aims to focus on testing various lunar ISRU processes by landing several payloads on multiple commercial robotic landers and rovers. The first payload contracts were awarded on February 21, 2019,[110][111] and will fly on separate missions. The CLPS will inform and support NASA's Artemis program, leading to a crewed lunar outpost for extended stays.[106]

A European non-profit organization has called for a global synergistic collaboration between all space agencies and nations instead of a "Moon race"; this proposed collaborative concept is called the Moon Village.[112] Moon Village seeks to create a vision where both international cooperation and the commercialization of space can thrive.[113][114][115]

Some early private companies like Shackleton Energy Company,[116] Deep Space Industries, Planetoid Mines, Golden Spike Company, Planetary Resources, Astrobotic Technology, and Moon Express are planning private commercial scouting and mining ventures on the Moon.[1][117]

In 2024, an American startup called Interlune announced plans to mine Helium on the Moon for export back on Earth. The first mission plans to use NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services program to arrive on the Moon.[118]

Extraction methods

The extensive lunar maria are composed of basaltic lava flows. Their mineralogy is dominated by a combination of five minerals: anorthites (CaAl2Si2O8), orthopyroxenes ((Mg,Fe)SiO3), clinopyroxenes (Ca(Fe,Mg)Si2O6), olivines ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4), and ilmenite (FeTiO3),[1][48] all abundant on the Moon.[119] It has been proposed that smelters could process the basaltic lava to break it down into pure calcium, aluminium, oxygen, iron, titanium, magnesium, and silica glass.[120] The European Space Agency has awarded funding to Metalysis in 2020 to further develop the FFC Cambridge process to extract titanium from regolith while generating oxygen as a byproduct.[121] Raw lunar anorthite could also be used for making fiberglass and other ceramic products.[120][44] Another proposal envisions the use of fluorine brought from Earth as potassium fluoride to separate the raw materials from the lunar rocks.[122]

Legal status of mining

Although Luna landers scattered pennants of the Soviet Union on the Moon, and United States flags were symbolically planted at their landing sites by the Apollo astronauts, no nation claims ownership of any part of the Moon's surface,[123] and the international legal status of mining space resources is unclear and controversial.[124][125]

The five treaties and agreements[126] of international space law cover "non-appropriation of outer space by any one country, arms control, the freedom of exploration, liability for damage caused by space objects, the safety and rescue of spacecraft and astronauts, the prevention of harmful interference with space activities and the environment, the notification and registration of space activities, scientific investigation and the exploitation of natural resources in outer space and the settlement of disputes."[127]

Russia, China, and the United States are party to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST),[128] which is the most widely adopted treaty, with 104 parties.[129] The OST treaty offers imprecise guidelines to newer space activities such as lunar and asteroid mining,[130] and it therefore remains under contention whether the extraction of resources falls within the prohibitive language of appropriation or whether the use encompasses the commercial use and exploitation. Although its applicability on exploiting natural resources remains in contention, leading experts generally agree with the position issued in 2015 by the International Institute of Space Law (ISSL) stating that, "in view of the absence of a clear prohibition of the taking of resources in the Outer Space Treaty, one can conclude that the use of space resources is permitted."[131]

The 1979 Moon Treaty is a proposed framework of laws to develop a regime of detailed rules and procedures for orderly resource exploitation.[132][133] This treaty would regulate exploitation of resources if it is "governed by an international regime" of rules (Article 11.5),[134] but there has been no consensus and the precise rules for commercial mining have not been established.[135] The Moon Treaty was ratified by very few nations, and thus suggested to have little to no relevancy in international law.[136][137] The last attempt to define acceptable detailed rules for exploitation, ended in June 2018, after S. Neil Hosenball, who was the NASA General Counsel and chief US negotiator for the Moon Treaty, decided that negotiation of the mining rules in the Moon Treaty should be delayed until the feasibility of exploitation of lunar resources had been established.[138]

Seeking clearer regulatory guidelines, private companies in the US prompted the US government, and legalized space mining in 2015 by introducing the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015.[139] Similar national legislations legalizing extraterrestrial appropriation of resources are now being replicated by other nations, including Luxembourg, Japan, China, India and Russia.[130][140][141][142] This has created an international legal controversy on mining rights for profit.[140][137] A legal expert stated in 2011 that the international issues "would probably be settled during the normal course of space exploration."[137] In April 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order to support moon mining.[143]

See also

- Colonization of the Moon – Settlement on the Moon

- Exploration of the Moon – Missions to the Moon

- Geology of the Moon – Structure and composition of the Moon

- In situ resource utilization

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Crawford, Ian (2015). "Lunar Resources: A Review". Progress in Physical Geography. 39 (2): 137–167. arXiv:1410.6865. Bibcode:2015PrPhG..39..137C. doi:10.1177/0309133314567585. S2CID 54904229.

- ^ Yuhao Lu and Ramaa G. Reddy. Extraction of Metals and Oxygen from Lunar Soil. Archived 2021-11-23 at the Wayback Machine Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering; The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. USA. 9 January 2009.

- ^ a b M. Anand, I. A. Crawford, M. Balat-Pichelin, S. Abanades, W. van Westrenen, G. Péraudeau, R. Jaumann, W. Seboldt. "Moon and likely initial in situ resource utilization (ISRU) applications." Planetary and Space Science; volume 74; issue 1; December 2012, pp: 42—48. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2012.08.012.

- ^ Gerald B. Sanders, Micael Dule. NASA In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) Capability Roadmap Final Report. Archived 2020-09-05 at the Wayback Machine. May 19, 2005.

- ^ S. A. Bailey. "Lunar Resource Prospecting". Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ D. C. Barker. "Lunar Resources: From Finding to Making Demand." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ J. L. Heldmann, A. C. Colaprete, R. C. Elphic, and D. R. Andrews. "Landing Site Selection And Effects On Robotic Resource Prospecting Mission Operations." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ Alex Ignatiev and Elliot Carol. "The Use of a Lunar Vacuum Deposition Paver/Rover to Eliminate Hazardous Dust Plumes on the Lunar Surface." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ B. R. Blair. "Emarging Markets for Lunar Resources." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ a b David, Leonard (7 January 2015). "Is Moon Mining Economically Feasible?". Space.com.

- ^ Taylor, Stuart R. (1975). Lunar Science: a Post-Apollo View. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-08-018274-2.

- ^ Hugo, Adam (2020-06-24) [April 2019]. "Why the Lunar South Pole?". The Space Resource. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ S. Maurice. "Distribution of hydrogen at the surface of the moon" (PDF).

- ^ a b Laurent Sibille, William Larson. Oxygen from Regolith. Archived 2020-09-05 at the Wayback Machine. NASA. 3 July 2012.

- ^ a b Gregory Bennett. The Artemis Project – How to Get Oxygen from the Moon Archived 2020-09-05 at the Wayback Machine. Artemis Society International. June 17, 2001.

- ^ Administrator, NASA (2013-06-07). "Is There an Atmosphere on the Moon?". NASA. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ "Moon Fact Sheet". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Speyerer, Emerson J.; Robinson, Mark S. (2013). "Persistently illuminated regions at the lunar poles: Ideal sites for future exploration". Icarus. 222 (1): 122–136. Bibcode:2013Icar..222..122S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.10.010. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Gläser, P., Oberst, J., Neumann, G. A., Mazarico, E., Speyerer, E. J., Robinson, M. S. (2017). "Illumination conditions at the lunar poles: Implications for future exploration. Planetary and Space Science, vol. 162, p. 170–178. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2017.07.006

- ^ a b Spudis, Paul D. (2011). "Lunar Resources: Unlocking the Space Frontier". Ad Astra. National Space Society. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Alex Ignatiev, Peter Curreri, Donald Sadoway, and Elliot Carol. "The Use of Lunar Resources for Energy Generation on the Moon." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (2005-12-01). Materials Refining for Solar Array Production on the Moon (Report).

- ^ Skocii, Collin (18 June 2019). "NASA concept for generating power in deep space a little KRUSTY". Spaceflight Insider.

- ^ a b Anderson, Gina; Wittry, Jan (May 2, 2018). "Demonstration Proves Nuclear Fission System Can Provide Space Exploration Power". NASA press release. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ a b David, Leonard (2019-03-15). "Moon Mining Could Actually Work, with the Right Approach". Space.com. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ a b c Allen, Carlton C.; McKay, David S. (1995). "Oxygen Production From Lunar Soil". SAE Transactions. 104: 1285–1290. ISSN 0096-736X. JSTOR 44612041.

- ^ Wiechert, U.; Halliday, A. N.; Lee, D.-C.; Snyder, G. A.; Taylor, L. A.; Rumble, D. (2001). "Oxygen Isotopes and the Moon-Forming Giant Impact". Science. 294 (5541): 345–348. Bibcode:2001Sci...294..345W. doi:10.1126/science.1063037. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 3084837. PMID 11598294. S2CID 29835446.

- ^ Hepp, Aloysius F.; Linne, Diane L.; Groth, Mary F.; Landis, Geoffrey A.; Colvin, James E. (1994). "Production and use of metals and oxygen for lunar propulsion". Journal of Propulsion and Power. 10 (16): 834–840. doi:10.2514/3.51397. hdl:2060/19910019908. S2CID 120318455.

- ^ Larry Friesen. Processes for Getting Oxygen on the Moon. Archived 2022-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Artemis Society International. 10 May 1998.

- ^ "Ice Confirmed at the Moon's Poles". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). 20 August 2018. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ "Water on the Moon: Direct evidence from Chandrayaan-1's Moon Impact…". The Planetary Society. April 7, 2010. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ H. M. Brown. "Identifying Resource-rich Lunar Permanently Shadowed Regions." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ a b c J. E. Gruener. "The Lunar Northwest Nearside: The Price Is Right Before Your Eyes." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ David, Leonard (13 July 2018). "Mining Moon Ice: Prospecting Plans Starting to Take Shape". Space.com.

- ^ a b L. M. Jozwiak, G. W. Patterson, R. Perkins. "Mini-RF Monostatic Radar Observations of Permanently Shadowed Crater Floors." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ Elston, D. P. (1968) "Character and Geologic Habitat of Potential Deposits of Water, Carbon and Rare Gases on the Moon", Geological Problems in Lunar and Planetary Research, Proceedings of AAS/IAP Symposium, AAS Science and Technology Series, Supplement to Advances in the Astronautical Sciences., p. 441.

- ^ "NASA – Lunar Prospector". lunar.arc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ^ Steigerwald, Bill (2015-02-27). "LRO Discovers Hydrogen More Abundant on Moon's Pole-Facing Slopes". NASA. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ H. L. Hanks. "Prospective Study for Harvesting Solar Wind Particles via Lunar Regolith Capture." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ P. Reiss, F. Kerscher and L. Grill. "Thermogravimetric Analysis of the Reduction of ilmenite and NU-LHT-2M With Hydrogen and Methane." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ H. M. Sargeant, F. Abernethy, M. Anand1, S. J. Barber, S. Sheridan, I. Wright, and A. Morse. "Experimental Development And Testing Of The Reduction Of Ilmenite For A Lunar ISRU Demonstration With PRO SPA." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ J. W. Quinn. "Electrostatic Beneficiation of Lunar Regolith; A review of the Previous Testing As Starting Point For Future Work." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ "Exploring the Moon – A Teacher's Guide with Activities, NASA EG-1997-10-116 - Rock ABCs Fact Sheet" (PDF). NASA. November 1997. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mark Prado. Major Lunar Minerals. Archived 2019-08-01 at the Wayback Machine. Projects to Employ Resources of the Moon and Asteroids Near Earth in the Near Term (PERMANENT). Accessed on 1 August 2019.

- ^ "The Moon Is Rusting, and Researchers Want to Know Why". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Space com Staff (2011-10-11). "Moon Packed with Precious Titanium, NASA Probe Finds". Space.com. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ "SMART-1 detects calcium on the Moon". www.esa.int. 8 June 2005. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ a b Deer, W. A.; Howie, R. A.; Zussman, J. (1966). An Introduction to the Rock Forming Minerals. London, England: Longman. p. 336. ISBN 0-582-44210-9.

- ^ A. Ignatiev and A. Freundlich. New Architecture for Space Solar Power Systems: Fabrication of Silicon Solar Cells Using In-Situ Resources. Archived 2019-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. NIAC 2nd Annual Meeting, June 6–7, 2000.

- ^ Rao, D. B.; Choudary, U. V.; Erstfeld, T. E.; Williams, R. J.; Chang, Y. A. (1979-01-01). "Extraction processes for the production of aluminum, titanium, iron, magnesium, and oxygen and nonterrestrial sources". NASA. Ames Research Center, Space Resources and Space Settlements.

- ^ Cordierite-Spinel Troctolite, a New Magnesium-Rich Lithology from the Lunar Highlands. Science. Vol 243, Issue 4893. 17 February 1989 {{doi}10.1126/science.243.4893.925}}.

- ^ a b Jolliff, B. L.; Tran, T. N.; Lawrence, S. J.; Robinson, M. S.; et al. (2011). Compton-Belkovich: Nonmare, Silicic Volcanism on the Moon's Far Side (PDF). 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ Lawrence, D. J.; Elphic, R. C.; Feldman, W. C.; Gasnault, O.; Genetay, I.; Maurice, S.; Prettyman, T. H. (March 2002). Small-Area Thorium Enhancements on the Lunar Surface. 33rd Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Harvard University. Bibcode:2002LPI....33.1970L.

- ^ "China may not issue new 2011 rare earths export quota: report". Reuters. 31 December 2010.

- ^ Medeiros, Carlos Aguiar De; Trebat, Nicholas M.; Medeiros, Carlos Aguiar De; Trebat, Nicholas M. (July 2017). "Transforming natural resources into industrial advantage: the case of China's rare earths industry". Brazilian Journal of Political Economy. 37 (3): 504–526. doi:10.1590/0101-31572017v37n03a03. ISSN 0101-3157.

- ^ Haxel, G.; Hedrick, J.; Orris, J. (2002). Stauffer, Peter H.; Hendley II, James W. (eds.). "Rare Earth Elements—Critical Resources for High Technology" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. USGS Fact Sheet: 087-02. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

However, in contrast to ordinary base and precious metals, REE have very little tendency to become concentrated in exploitable ore deposits. Consequently, most of the world's supply of REE comes from only a handful of sources.

- ^ Goldman, Joanne Abel (April 2014). "The U.S. Rare Earth Industry: Its Growth and Decline". Journal of Policy History. 26 (2): 139–166. doi:10.1017/s0898030614000013. ISSN 0898-0306. S2CID 154319330.

- ^ Tse, Pui-Kwan. "USGS Report Series 2011–1042: China's Rare-Earth Industry". pubs.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ A. A. Mardon, G. Zhou, R. Witiw. "Lunar Rare-Earth Minerals For Commercialization." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ a b "The Lunar Gold Rush: How Moon Mining Could Work". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). May 28, 2019. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ L. J. Wittenberg, E. N. Cameron, G. L. Kulcinski, S. H. Ott, J. F. Santarius, G. I. Sviatoslavsky, I. N. SViatoslavsky & H. E. Thompson. A Review of 3He Resources and Acquisition for Use as Fusion Fuel. Archived 2020-05-14 at the Wayback Machine. Fusion Technology, volume 21, 1992; issue 4; pp: 2230–2253; 9 May 2017. doi:10.13182/FST92-A29718.

- ^ FTI Research Projects: 3He Lunar Mining Archived 2006-09-04 at the Wayback Machine. Fti.neep.wisc.edu. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ E. N. Slyuta; A. M. Abdrakhimov; E. M. Galimov (2007). "The estimation of helium-3 probable reserves in lunar regolith" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVIII (1338): 2175. Bibcode:2007LPI....38.2175S.

- ^ Cocks, F. H. (2010). "3He in permanently shadowed lunar polar surfaces". Icarus. 206 (2): 778–779. Bibcode:2010Icar..206..778C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.12.032.

- ^ Hedman, Eric R. (January 16, 2006). "A fascinating hour with Gerald Kulcinski". The Space Review.

- ^ "Korean fusion reactor achieves record plasma – World Nuclear News". www.world-nuclear-news.org. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ "Fusion reactor – Principles of magnetic confinement". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ a b c Day, Dwayne (September 28, 2015). "The helium-3 incantation". The Space Review. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Nuclear Fusion: WNA". world-nuclear.org. November 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-07-19. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ Sviatoslavsky, I. N. (November 1993). "The challenge of mining He-3 on the lunar surface: how all the parts fit together" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-20. Retrieved 2019-07-22. Wisconsin Center for Space Automation and Robotics Technical Report WCSAR-TR-AR3-9311-2.

- ^ David, Leonard (4 March 2003). "China Outlines its Lunar Ambitions". Space.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ^ "DOE National Laboratory Makes History by Achieving Fusion Ignition". Energy.gov. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Carbon on the Moon. Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine Artemis Society International. 8 August 1999.

- ^ Colin Trevor Pillinger and Geoffrey Eglinton. "The chemistry of carbon in the lunar regolith." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 1 January 1997. doi:10.1098/rsta.1977.0076.

- ^ American Geophysical Union. "Carbon dioxide cold traps on the moon are confirmed for the first time". phys.org. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Cannon, Kevin M. (2021-04-27). "Accessible Carbon on the Moon". arXiv:2104.13521 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ a b Richard H. Becker and Robert N. Clayton. Nitrogen abundances and isotopic compositions in lunar samples Archived 2019-07-23 at the Wayback Machine. Proceedings Lunar Science Conference, 6th (1975); pp: 2131–2149. Bibcode:1975LPSC....6.2131B.

- ^ Füri, Evelyn; Barry, Peter H.; Taylor, Lawrence A.; Marty, Bernard (2015). "Indigenous nitrogen in the Moon: Constraints from coupled nitrogen–noble gas analyses of mare basalts". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 431: 195–205. Bibcode:2015E&PSL.431..195F. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2015.09.022. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Mortimer, J.; Verchovsky, A. B.; Anand, M. (2016-11-15). "Predominantly non-solar origin of nitrogen in lunar soils". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 193: 36–53. Bibcode:2016GeCoA.193...36M. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2016.08.006. ISSN 0016-7037. S2CID 99355135.

- ^ a b c Brad Buckles, Robert P. Mueller, and Nathan Gelino. "Additive Construction Technology For Lunar Infrastructure." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019.

- ^ a b A. K. Hayes, P. Ye, D. A. Loy, K. Muralidharan, B. G. Potter, and J. J. Barnes. "Additive Manufacturing of Lunar Mineral-Based Composites." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019.

- ^ "Indigenous lunar construction materials". AIAA PAPER 91-3481. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^ "In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) – NASA". Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ "Cast Basalt" (PDF). Ultratech. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^ Gerald B. Sanders, William E. Larson. Title: Integration of In-Situ Resource Utilization Into Lunar/Mars Exploration Through Field Analogs. Archived 2019-07-23 at the Wayback Machine. NASA Johnson Space Center. 2010.

- ^ Tucker, Dennis S.; Ethridge, Edwin C. (May 11, 1998). Processing Glass Fiber from Moon/Mars Resources (PDF). Proceedings of American Society of Civil Engineers Conference, 26–30 April 1998. Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States. 19990104338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2000-09-18.

- ^ Naeye, Robert (6 April 2008). "NASA Scientists Pioneer Method for Making Giant Lunar Telescopes". Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Lowman, Paul D.; Lester, Daniel F. (November 2006). "Build astronomical observatories on the Moon?". Physics Today. Vol. 59, no. 11. p. 50. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ^ Bell, Trudy (9 October 2008). "Liquid Mirror Telescopes on the Moon". Science News. NASA. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Chandler, David (15 February 2008). "MIT to lead development of new telescopes on moon". MIT News. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Lunar Dirt Factories? A look at how regolith could be the key to permanent outposts on the moon". The Space Monitor. 2007-06-18. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Blacic, James D. (1985). "Mechanical Properties of Lunar Materials Under Anhydrous, Hard Vacuum Conditions: Applications of Lunar Glass Structural Components". Lunar Bases and Space Activities of the 21st Century: 487–495. Bibcode:1985lbsa.conf..487B.

- ^ "Building a lunar base with 3D printing / Technology / Our Activities / ESA". Esa.int. 2013-01-31. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ "Foster + Partners works with European Space Agency to 3D print structures on the moon". Foster + Partners. 31 January 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ a b Diaz, Jesus (2013-01-31). "This Is What the First Lunar Base Could Really Look Like". Gizmodo. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- ^ "NASA's plan to build homes on the Moon: Space agency backs 3D print technology which could build base". TechFlesh. 2014-01-15. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ^ Steadman, Ian (1 March 2013). "Giant Nasa spider robots could 3D print lunar base using microwaves (Wired UK)". Wired UK. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ a b c A. A. Ellery. "Sustainable Lunar In-Situ Resource Utilization = Long-Term Planning." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ G. Harmer. "Integrating ISRU Projects to Create A Sustainable In-Space Economy." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ A. A. Mardon, G. Zhou, R. Witiw. "Ethical Conduct in Lunar Commercialization." Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah (21 January 2019). "Battlefield moon: how China plans to win the lunar space race". The Guardian.

- ^ Bender, Bryan (13 June 2019). "A new moon race is on. Is China already ahead?". Politico.

- ^ "China has no timetable for manned moon landing: chief scientist". Xinhua. 19 September 2012. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012.

- ^ "Russia Plans to Colonize Moon by 2030, Newspaper Reports". The Moscow Times. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Litvak, Maxim (2016). "The vision of the Russian Space Agency on the robotic settlements in the Moon" (PDF). IKI/Roscosmos.

- ^ a b Moon to Mars. Archived 2019-07-25 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Accessed on 23 July 2019.

- ^ a b Grush, Loren (April 27, 2018). "NASA scraps a lunar surface mission – just as it's supposed to focus on a Moon return". The Verge.

- ^ a b Berger, Eric (27 April 2018). "New NASA leader faces an early test on his commitment to Moon landings". ARS Technica.

- ^ Resource Prospector Archived 2019-03-08 at the Wayback Machine. Advanced Exploration Systems, NASA. 2017.

- ^ Richardson, Derek (February 26, 2019). "NASA selects experiments to fly aboard commercial lunar landers". Spaceflight Insider.

- ^ Szondy, David (21 February 2019). "NASA picks 12 lunar experiments that could fly this year". New Atlas.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (26 December 2018). "Urban planning for the Moon Village". Space News.

- ^ Jan Wörner, ESA Director General. Moon Village: A vision for global cooperation and Space 4.0 Archived 2019-10-16 at the Wayback Machine. April 2016.

- ^ David, Leonard (2016-04-26). "Europe Aiming for International 'Moon Village'". Space.com. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ Moon Village: humans and robots together on the Moon Archived 2019-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. ESA. 1 March 2016.

- ^ Wall, Mike (14 January 2011). "Mining the Moon's Water: Q&A with Shackleton Energy's Bill Stone". space.com. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ Hennigan, W. J. (2011-08-20). "MoonEx aims to scour Moon for rare materials". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

MoonEx's machines are designed to look for materials that are scarce on Earth but found in everything from a Toyota Prius car battery to guidance systems on cruise missiles.

- ^ Eaton, Kit (Mar 14, 2024). "Space Startup Interlune Emerges From Stealth Mode to Start Moon Mining Effort".

- ^ "Significant Lunar Minerals" (PDF). In Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Mining and Manufacturing on the Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^ "Metalysis gets ESA development contract for FFC process". Institute of Materials, Minerals & Mining.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey. "Refining Lunar Materials for Solar Array Production on the Moon" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-09. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ "Can any State claim a part of outer space as its own?". United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ David, Leonard (25 July 2014). "Mining the Moon? Space Property Rights Still Unclear, Experts Say". Space.com.

- ^ Wall, Mike (14 January 2011). "Moon Mining Idea Digs Up Lunar Legal Issues". Space.com.

- ^

- The 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the "Outer Space Treaty").

- The 1968 Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the "Rescue Agreement").

- The 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (the "Liability Convention").

- The 1975 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the "Registration Convention").

- The 1979 Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the "Moon Treaty").

- ^ United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. "United Nations Treaties and Principles on Space Law". unoosa.org. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "How many States have signed and ratified the five international treaties governing outer space?". United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. 1 January 2006. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Legal Subcommittee: Fifty-fifth session. Archived 2019-01-19 at the Wayback Machine Vienna, Austria, 4–15 April 2016. Item 6 of the provisional agenda: Status and application of the five United Nations treaties on outer space.

- ^ a b Senjuti Mallick and Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan. If space is 'the province of mankind', who owns its resources? Archived 2020-05-10 at the Wayback Machine.The Observer Research Foundation. 24 January 2019. Quote 1: "The Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967, considered the global foundation of the outer space legal regime, […] has been insufficient and ambiguous in providing clear regulations to newer space activities such as asteroid mining." *Quote2: "Although the OST does not explicitly mention "mining" activities, under Article II, outer space including the Moon and other celestial bodies are "not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty" through use, occupation or any other means."

- ^ "Institutional Framework for the Province of all Mankind: Lessons from the International Seabed Authority for the Governance of Commercial Space Mining." Jonathan Sydney Koch. "Institutional Framework for the Province of all Mankind: Lessons from the International Seabed Authority for the Governance of Commercial Space Mining." Astropolitics, 16:1, 1–27, 2008. doi:10.1080/14777622.2017.1381824

- ^ Louis de Gouyon Matignon. The 1979 Moon Agreement. Archived 2019-11-06 at the Wayback Machine. Space Legal Issues. 17 July 2019.

- ^ J. K. Schingler and A. Kapoglou. "Common Pool Lunar Resources." Archived 2020-07-25 at the Wayback Machine. Lunar ISRU 2019: Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. July 15–17, 2019, Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ United Nations (5 December 1979). "Moon Agreement". www.unoosa.org. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

Resolution 34/68 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. 89th plenary meeting; 5 December 1979.

- ^ Fabio Tronchetti. Current International Legal Framework Applicability to Space Resource Activities. Archived 2020-10-20 at the Wayback Machine. IISL/ECSL Space Law Symposium 2017, Vienna, Austria. 27 March 2017.

- ^ Listner, Michael (24 October 2011). "The Moon Treaty: failed international law or waiting in the shadows?". The Space Review.

- ^ a b c James R. Wilson. Regulation of the Outer Space Environment Through International Accord: The 1979 Moon Treaty. Archived 2020-08-03 at the Wayback Machine. Fordham Environmental Law Review, Volume 2, Number 2, Article 1, 2011.

- ^ Beldavs, Vidvuds (15 January 2018). "Simply fix the Moon Treaty". The Space Review.

- ^ H.R. 2262 – U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. 114th Congress (2015–2016) Archived 2015-11-19 at the Wayback Machine. Sponsor: Representative McCarthy, Kevin. 5 December 2015.

- ^ a b Davies, Rob (6 February 2016). "Asteroid mining could be space's new frontier: the problem is doing it legally". The Guardian.

- ^ Ridderhof, R. (18 December 2015). "Space Mining and (U.S.) Space Law". Peace Palace Library. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Law Provides New Regulatory Framework for Space Commerce | RegBlog". www.regblog.org. 31 December 2015. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ^ Wall, Mike (6 April 2020). "Trump signs executive order to support Moon mining, tap asteroid resources". Space.com.