Histopathology image classification: Highlighting the gap between manual analysis and AI automation

Communist Party of China 中国共产党 Zhōngguó Gòngchǎndǎng | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | CCP (common) CPC (official) |

| General Secretary | Xi Jinping |

| Standing Committee | |

| Founders |

... and others |

| Founded |

|

| Headquarters | Zhongnanhai, Xicheng District, Beijing |

| Newspaper | People's Daily |

| Youth wing | Communist Youth League of China |

| Children's wing | Young Pioneers of China |

| Armed wing | |

| Research office | Central Policy Research Office |

| Membership (2023) | |

| Ideology | |

| International affiliation | IMCWP |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | "Serve the People"[note 2] |

| National People's Congress (13th) | 2,090 / 2,980 |

| NPC Standing Committee (14th) | 117 / 175 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| 12371 | |

| Communist Party of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Communist Party of China" in simplified (top) and traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国共产党 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國共產黨 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōngguó Gòngchǎndǎng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abbreviation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 中共 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōnggòng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་གོ་གུང་ཁྲན་ཏང | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghgoz Gungcanjdangj | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Дундад улсын (Хятадын) Эв хамт (Kоммунист) Нам | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ ᠤᠨ (ᠬᠢᠲᠠᠳ ᠤᠨ) ᠡᠪ ᠬᠠᠮᠲᠤ (ᠺᠣᠮᠮᠤᠶᠢᠨᠢᠰᠲ) ᠨᠠᠮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭگو كوممۇنىستىك پارتىيىسى | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ ᡳ (ᠵᡠᠨᡤᠣ ᡳ) ᡤᡠᠩᡮᠠᠨ ᡥᠣᡴᡳ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai gurun-i (Jungg'o-i) Gungcan Hoki | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP),[3] officially the Communist Party of China (CPC),[4] is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War against the Kuomintang. In 1949, Mao proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China. Since then, the CCP has governed China and has had sole control over the People's Liberation Army (PLA). Successive leaders of the CCP have added their own theories to the party's constitution, which outlines the party's ideology, collectively referred to as socialism with Chinese characteristics. As of 2024, the CCP has more than 99 million members, making it the second largest political party by membership in the world after India's Bharatiya Janata Party.

In 1921, Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao led the founding of the CCP with the help of the Far Eastern Bureau of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and Far Eastern Bureau of the Communist International. For the first six years, the CCP aligned itself with the Kuomintang (KMT) as the organized left wing of the larger nationalist movement. However, when the right wing of the KMT, led by Chiang Kai-shek, turned on the CCP and massacred tens of thousands of the party's members, the two parties split and began a prolonged civil war. During the next ten years of guerrilla warfare, Mao Zedong rose to become the most influential figure in the CCP, and the party established a strong base among the rural peasantry with its land reform policies. Support for the CCP continued to grow throughout the Second Sino-Japanese War, and after the Japanese surrender in 1945, the CCP emerged triumphant in the communist revolution against the Nationalist government. After the KMT's retreat to Taiwan, the CCP established the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949.

Mao Zedong continued to be the most influential member of the CCP until his death in 1976, although he periodically withdrew from public leadership as his health deteriorated. Under Mao, the party completed its land reform program, launched a series of five-year plans, and eventually split with the Soviet Union. Although Mao attempted to purge the party of capitalist and reactionary elements during the Cultural Revolution, after his death, these policies were only briefly continued by the Gang of Four before a less radical faction seized control. During the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping directed the CCP away from Maoist orthodoxy and towards a policy of economic liberalization. The official explanation for these reforms was that China was still in the primary stage of socialism, a developmental stage similar to the capitalist mode of production. Since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the CCP has focused on maintaining its relations with the ruling parties of the remaining socialist states and continues to participate in the International Meeting of Communist and Workers' Parties each year. The CCP has also established relations with several non-communist parties, including dominant nationalist parties of many developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, as well as social democratic parties in Europe.

The Chinese Communist Party is organized based on democratic centralism, a principle that entails open policy discussion on the condition of unity among party members in upholding the agreed-upon decision. The highest body of the CCP is the National Congress, convened every fifth year. When the National Congress is not in session, the Central Committee is the highest body, but since that body usually only meets once a year, most duties and responsibilities are vested in the Politburo and its Standing Committee. Members of the latter are seen as the top leadership of the party and the state.[5] Today the party's leader holds the offices of general secretary (responsible for civilian party duties), Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) (responsible for military affairs), and State President (a largely ceremonial position). Because of these posts, the party leader is seen as the country's paramount leader. The current leader is Xi Jinping, who was elected at the 1st Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee held on 15 November 2012 and has been reelected twice, on 25 October 2017 by the 19th Central Committee and on 10 October 2022 by the 20th Central Committee.

History

Founding and early history

The October Revolution and Marxist theory inspired the founding of the CCP.[6]: 114 Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao were among the first to publicly support Leninism and world revolution. Both regarded the October Revolution in Russia as groundbreaking, believing it to herald a new era for oppressed countries everywhere.[7]

Some historical analysis views the May Fourth Movement as the beginning of the revolutionary struggle that led to the founding of the People's Republic of China.[8]: 22 Following the movement, trends towards social transformation increased.[9]: 14 Writing in 1939, Mao Zedong stated that the Movement had shown that the bourgeois revolution against imperialism and China had developed to a new stage, but that the proletariat would lead the revolution's completion.[9]: 20 The May Fourth Movement led to the establishment of radical intellectuals who went on to mobilize peasants and workers into the CCP and gain the organizational strength that would solidify the success of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[10] Chen and Li were among the most influential promoters of Marxism in China during the May Fourth period.[9]: 7 The CCP itself embraces the May Fourth Movement and views itself as part of the movement's legacy.[11]: 24

Study circles were, according to Cai Hesen, "the rudiments [of our party]".[12] Several study circles were established during the New Culture Movement, but by 1920 many grew sceptical about their ability to bring about reforms.[13] China's intellectual movements were fragmented in the early 1920s.[14]: 17 The May Fourth Movement and the New Culture Movement had identified issues of broad concern to Chinese progressives, including anti-imperialism, support for nationalism, support for democracy, promotion of feminism, and rejection of traditional values.[14]: 17 Proposed solutions among Chinese progressives differed significantly, however.[14]: 17

The CCP was founded on 1 July 1921 with the help of the Far Eastern Bureau of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and Far Eastern Secretariat of the Communist International, according to the party's official account of its history.[15][16] However, party documents suggest that the party's actual founding date was 23 July 1921, the first day of the 1st National Congress of the CCP.[17] The founding National Congress of the CCP was held 23–31 July 1921.[18][better source needed] With only 50 members in the beginning of 1921, among them Chen Duxiu, Li Dazhao and Mao Zedong,[19] the CCP organization and authorities grew tremendously.[6]: 115 While it was originally held in a house in the Shanghai French Concession, French police interrupted the meeting on 30 July[20] and the congress was moved to a tourist boat on South Lake in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province.[20] A dozen delegates attended the congress, with neither Li nor Chen being able to attend,[20] the latter sending a personal representative in his stead.[20] The resolutions of the congress called for the establishment of a communist party as a branch of the Communist International (Comintern) and elected Chen as its leader. Chen then served as the first general secretary of the CCP[20] and was referred to as "China's Lenin".[citation needed]

The Soviets hoped to foster pro-Soviet forces in East Asia to fight against anti-communist countries, particularly Japan. They attempted to contact the warlord Wu Peifu but failed.[21][22] The Soviets then contacted the Kuomintang (KMT), which was leading the Guangzhou government parallel to the Beiyang government. On 6 October 1923, the Comintern sent Mikhail Borodin to Guangzhou, and the Soviets established friendly relations with the KMT. The Central Committee of the CCP,[23] Soviet leader Joseph Stalin,[24] and the Comintern[25] all hoped that the CCP would eventually control the KMT and called their opponents "rightists".[26][note 3] KMT leader Sun Yat-sen eased the conflict between the communists and their opponents. CCP membership grew tremendously after the 4th congress in 1925, from 900 to 2,428.[28] The CCP still treats Sun Yat-sen as one of the founders of their movement and claim descent from him[29] as he is viewed as a proto-communist[30] and the economic element of Sun's ideology was socialism.[31] Sun stated, "Our Principle of Livelihood is a form of communism".[32]

The communists dominated the left wing of the KMT and struggled for power with the party's right-wing factions.[26] When Sun Yat-sen died in March 1925, he was succeeded by a rightist, Chiang Kai-shek, who initiated moves to marginalize the position of the communists.[26] Chiang, Sun's former assistant, was not actively anti-communist at that time,[33] even though he hated the theory of class struggle and the CCP's seizure of power.[27] The communists proposed removing Chiang's power.[34] When Chiang gradually gained the support of Western countries, the conflict between him and the communists became more and more intense. Chiang asked the Kuomintang to join the Comintern to rule out the secret expansion of communists within the KMT, while Chen Duxiu hoped that the communists would completely withdraw from the KMT.[35]

In April 1927, both Chiang and the CCP were preparing for conflict.[36] Fresh from the success of the Northern Expedition to overthrow the warlords, Chiang Kai-shek turned on the communists, who by now numbered in the tens of thousands across China.[37] Ignoring the orders of the Wuhan-based KMT government, he marched on Shanghai, a city controlled by communist militias. Although the communists welcomed Chiang's arrival, he turned on them, massacring 5,000[note 4] with the aid of the Green Gang.[37][40][41] Chiang's army then marched on Wuhan but was prevented from taking the city by CCP General Ye Ting and his troops.[42] Chiang's allies also attacked communists; for example, in Beijing, Li Dazhao and 19 other leading communists were executed by Zhang Zuolin.[43][38] Angered by these events, the peasant movement supported by the CCP became more violent. Ye Dehui, a famous scholar, was killed by communists in Changsha, and in revenge, KMT general He Jian and his troops gunned down hundreds of peasant militiamen.[44] That May, tens of thousands of communists and their sympathizers were killed by KMT troops, with the CCP losing approximately 15,000 of its 25,000 members.[38]

Chinese Civil War and Second Sino-Japanese War

The CCP continued supporting the Wuhan KMT government,[38] but on 15 July 1927 the Wuhan government expelled all communists from the KMT.[45] The CCP reacted by founding the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China, better known as the "Red Army", to battle the KMT. A battalion led by General Zhu De was ordered to take the city of Nanchang on 1 August 1927 in what became known as the Nanchang uprising.

Initially successful, Zhu and his troops were forced to retreat after five days, marching south to Shantou, and from there being driven into the wilderness of Fujian.[45] Mao Zedong was appointed commander-in-chief of the Red Army, and led four regiments against Changsha in the Autumn Harvest Uprising, hoping to spark peasant uprisings across Hunan.[46] His plan was to attack the KMT-held city from three directions on 9 September, but the Fourth Regiment deserted to the KMT cause, attacking the Third Regiment. Mao's army made it to Changsha but could not take it; by 15 September, he accepted defeat, with 1,000 survivors marching east to the Jinggang Mountains of Jiangxi.[46][47][48]

The near destruction of the CCP's urban organizational apparatus led to institutional changes within the party.[49] The party adopted democratic centralism, a way to organize revolutionary parties, and established a politburo to function as the standing committee of the central committee.[49] The result was increased centralization of power within the party.[49] At every level of the party this was duplicated, with standing committees now in effective control.[49] After being expelled from the party, Chen Duxiu went on to lead China's Trotskyist movement. Li Lisan was able to assume de facto control of the party organization by 1929–1930.[49]

The 1929 Gutian Congress was important in establishing the principle of party control over the military, which continues to be a core principle of the party's ideology.[50]: 280

Li's leadership was a failure, leaving the CCP on the brink of destruction.[49] The Comintern became involved, and by late 1930, his powers had been taken away.[49] By 1935, Mao had become a member of Politburo Standing Committee of the CCP and the party's informal military leader, with Zhou Enlai and Zhang Wentian, the formal head of the party, serving as his informal deputies.[49] The conflict with the KMT led to the reorganization of the Red Army, with power now centralized in the leadership through the creation of CCP political departments charged with supervising the army.[49]

The Xi'an Incident of December 1936 paused the conflict between the CCP and the KMT.[51] Under pressure from Marshal Zhang Xueliang and the CCP, Chiang Kai-shek finally agreed to a Second United Front focused on repelling the Japanese invaders.[52] While the front formally existed until 1945, all collaboration between the two parties had effectively ended by 1940.[52] Despite their formal alliance, the CCP used the opportunity to expand and carve out independent bases of operations to prepare for the coming war with the KMT.[53] In 1939, the KMT began to restrict CCP expansion within China.[53] This led to frequent clashes between CCP and KMT forces[53] which subsided rapidly on the realization on both sides that civil war amidst a foreign invasion was not an option.[53] By 1943, the CCP was again actively expanding its territory at the expense of the KMT.[53]

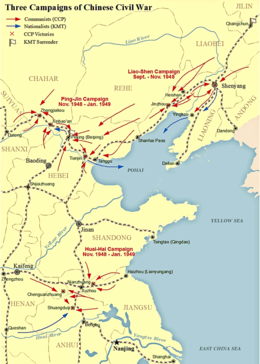

Mao Zedong became the Chairman of the CCP in 1945. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, the war between the CCP and the KMT began again in earnest.[54] The 1945–1949 period had four stages; the first was from August 1945 (when the Japanese surrendered) to June 1946 (when the peace talks between the CCP and the KMT ended).[54] By 1945, the KMT had three times more soldiers under its command than the CCP and initially appeared to be prevailing.[54] With the cooperation of the US and Japan, the KMT was able to retake major parts of the country.[54] However, KMT rule over the reconquered territories proved unpopular because of its endemic political corruption.[54]

Notwithstanding its numerical superiority, the KMT failed to reconquer the rural territories which made up the CCP's stronghold.[54] Around the same time, the CCP launched an invasion of Manchuria, where they were assisted by the Soviet Union.[54] The second stage, lasting from July 1946 to June 1947, saw the KMT extend its control over major cities such as Yan'an, the CCP headquarters, for much of the war.[54] The KMT's successes were hollow; the CCP had tactically withdrawn from the cities, and instead undermined KMT rule there by instigating protests among students and intellectuals. The KMT responded to these demonstrations with heavy-handed repression.[55] In the meantime, the KMT was struggling with factional infighting and Chiang Kai-shek's autocratic control over the party, which weakened its ability to respond to attacks.[55]

The third stage, lasting from July 1947 to August 1948, saw a limited counteroffensive by the CCP.[55] The objective was clearing "Central China, strengthening North China, and recovering Northeast China."[56] This operation, coupled with military desertions from the KMT, resulted in the KMT losing 2 million of its 3 million troops by the spring of 1948, and saw a significant decline in support for KMT rule.[55] The CCP was consequently able to cut off KMT garrisons in Manchuria and retake several territories.[56]

The last stage, lasting from September 1948 to December 1949, saw the communists go on the offensive and the collapse of KMT rule in mainland China as a whole.[56] Mao's proclamation of the founding of the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949 marked the end of the second phase of the Chinese Civil War (or the Chinese Communist Revolution, as it is called by the CCP).[56]

Proclamation of the PRC and the 1950s

Mao proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) before a massive crowd at Tiananmen Square on 1 October 1949. The CCP headed the Central People's Government.[6]: 118 From this time through the 1980s, top leaders of the CCP (such as Mao Zedong, Lin Biao, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping) were largely the same military leaders prior to the PRC's founding.[57] As a result, informal personal ties between political and military leaders dominated civil-military relations.[57]

Stalin proposed a one-party constitution when Liu Shaoqi visited the Soviet Union in 1952.[58] The constitution of the PRC in 1954 subsequently abolished the previous coalition government and established the CCP's one-party system.[59][60] In 1957, the CCP launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign against political dissidents and prominent figures from minor parties, which resulted in the political persecution of at least 550,000 people. The campaign significantly damaged the limited pluralistic nature in the socialist republic and solidified the country's status as a de facto one-party state.[61][62]

The Anti-Rightist Campaign led to the catastrophic results of the Second Five Year Plan from 1958 to 1962, known as the Great Leap Forward. In an effort to transform the country from an agrarian economy into an industrialized one, the CCP collectivized farmland, formed people's communes, and diverted labour to factories. General mismanagement and exaggerations of harvests by CCP officials led to the Great Chinese Famine, which resulted in an estimated 15 to 45 million deaths,[63][64] making it the largest famine in recorded history.[65][66][67]

Sino-Soviet split and Cultural Revolution

During the 1960s and 1970s, the CCP experienced a significant ideological separation from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union which was going through a period of "de-Stalinization" under Nikita Khrushchev.[68] By that time, Mao had begun saying that the "continued revolution under the dictatorship of the proletariat" stipulated that class enemies continued to exist even though the socialist revolution seemed to be complete, leading to the Cultural Revolution in which millions were persecuted and killed.[69] During the Cultural Revolution, party leaders such as Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, Peng Dehuai, and He Long were purged or exiled, and the Gang of Four, led by Mao's wife Jiang Qing, emerged to fill in the power vacuum left behind.

Reforms under Deng Xiaoping

Following Mao's death in 1976, a power struggle between CCP chairman Hua Guofeng and vice-chairman Deng Xiaoping erupted.[70] Deng won the struggle, and became China's paramount leader in 1978.[70] Deng, alongside Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, spearheaded the "reform and opening-up" policies, and introduced the ideological concept of socialism with Chinese characteristics, opening China to the world's markets.[71] In reversing some of Mao's "leftist" policies, Deng argued that a socialist state could use the market economy without itself being capitalist.[72] While asserting the political power of the CCP, the change in policy generated significant economic growth.[citation needed] This was justified on the basis that "Practice is the Sole Criterion for the Truth", a principle reinforced through a 1978 article that aimed to combat dogmatism and criticized the "Two Whatevers" policy.[73][better source needed] The new ideology, however, was contested on both sides of the spectrum, by Maoists to the left of the CCP's leadership, as well as by those supporting political liberalization. In 1981, the Party adopted a historical resolution, which assessed the historical legacy of the Mao Zedong era and the future priorities of the CCP.[74]: 6 With other social factors, the conflicts culminated in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre.[75] The protests having been crushed and the reformist party general secretary Zhao Ziyang under house arrest, Deng's economic policies resumed and by the early 1990s the concept of a socialist market economy had been introduced.[76] In 1997, Deng's beliefs (officially called "Deng Xiaoping Theory") were embedded into the CCP's constitution.[77]

Further reforms under Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao

CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin succeeded Deng as paramount leader in the 1990s and continued most of his policies.[78] In the 1990s, the CCP transformed from a veteran revolutionary leadership that was both leading militarily and politically, to a political elite increasingly renewed according to institutionalized norms in the civil bureaucracy.[57] Leadership was largely selected based on rules and norms on promotion and retirement, educational background, and managerial and technical expertise.[57] There is a largely separate group of professionalized military officers, serving under top CCP leadership largely through formal relationships within institutional channels.[57]

The CCP ratified Jiang's Three Represents concept for the 2003 revision of the party's constitution, as a "guiding ideology" to encourage the party to represent "advanced productive forces, the progressive course of China's culture, and the fundamental interests of the people."[79] The theory legitimized the entry of private business owners and bourgeois elements into the party.[79] Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin's successor as general secretary, took office in 2002.[80] Unlike Mao, Deng and Jiang Zemin, Hu laid emphasis on collective leadership and opposed one-man dominance of the political system.[80] The insistence on focusing on economic growth led to a wide range of serious social problems. To address these, Hu introduced two main ideological concepts: the "Scientific Outlook on Development" and "Harmonious Society".[81] Hu resigned from his post as CCP general secretary and Chairman of the CMC at the 18th National Congress held in 2012, and was succeeded in both posts by Xi Jinping.[82][83]

Leadership of Xi Jinping

Since taking power, Xi has initiated a wide-reaching anti-corruption campaign, while centralizing powers in the office of CCP general secretary at the expense of the collective leadership of prior decades.[84] Commentators have described the campaign as a defining part of Xi's leadership as well as "the principal reason why he has been able to consolidate his power so quickly and effectively."[85] Xi's leadership has also overseen an increase in the Party's role in China.[86] Xi has added his ideology, named after himself, into the CCP constitution in 2017.[87] Xi's term as general secretary was renewed in 2022.[57][88]

Since 2014, the CCP has led efforts in Xinjiang that involve the detention of more than 1 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in internment camps, as well as other repressive measures. This has been described as a genocide by some academics and some governments.[89][90] On the other hand, a greater number of countries signed a letter penned to the Human Rights Council supporting the policies as an effort to combat terrorism in the region.[91][92][93]

Celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the CCP's founding, one of the Two Centenaries, took place on 1 July 2021.[94] In the sixth plenary session of the 19th Central Committee in November 2021, CCP adopted a resolution on the Party's history, which for the first time credited Xi as being the "main innovator" of Xi Jinping Thought while also declaring Xi's leadership as being "the key to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation".[95][96] In comparison with the other historical resolutions, Xi's one did not herald a major change in how the CCP evaluated its history.[97]

On 6 July 2021, Xi chaired the Communist Party of China and World Political Parties Summit, which involved representatives from 500 political parties across 160 countries.[98] Xi urged the participants to oppose "technology blockades," and "developmental decoupling" in order to work towards "building a community with a shared future for mankind."[98]

Ideology

Formal ideology

The core ideology of the party has evolved with each distinct generation of Chinese leadership. As both the CCP and the People's Liberation Army promote their members according to seniority, it is possible to discern distinct generations of Chinese leadership.[99] In official discourse, each group of leadership is identified with a distinct extension of the ideology of the party. Historians have studied various periods in the development of the government of the People's Republic of China by reference to these "generations".[citation needed]

Marxism–Leninism was the first official ideology of the CCP.[100] According to the CCP, "Marxism–Leninism reveals the universal laws governing the development of history of human society."[100] To the CCP, Marxism–Leninism provides a "vision of the contradictions in capitalist society and of the inevitability of a future socialist and communist societies".[100] According to the People's Daily, Mao Zedong Thought "is Marxism–Leninism applied and developed in China".[100] Mao Zedong Thought was conceived not only by Mao Zedong, but by leading party officials, according to Xinhua News Agency.[101]

Deng Xiaoping Theory was added to the party constitution at the 14th National Congress in 1992.[77] The concepts of "socialism with Chinese characteristics" and "the primary stage of socialism" were credited to the theory.[77] Deng Xiaoping Theory can be defined as a belief that state socialism and state planning is not by definition communist, and that market mechanisms are class neutral.[102] In addition, the party needs to react to the changing situation dynamically; to know if a certain policy is obsolete or not, the party had to "seek truth from facts" and follow the slogan "practice is the sole criterion for the truth".[103] At the 14th National Congress, Jiang reiterated Deng's mantra that it was unnecessary to ask if something was socialist or capitalist, since the important factor was whether it worked.[104]

The "Three Represents", Jiang Zemin's contribution to the party's ideology, was adopted by the party at the 16th National Congress. The Three Represents defines the role of the CCP, and stresses that the Party must always represent the requirements for developing China's advanced productive forces, the orientation of China's advanced culture and the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people."[105][106] Certain segments within the CCP criticized the Three Represents as being un-Marxist and a betrayal of basic Marxist values. Supporters viewed it as a further development of socialism with Chinese characteristics.[107] Jiang disagreed, and had concluded that attaining the communist mode of production, as formulated by earlier communists, was more complex than had been realized, and that it was useless to try to force a change in the mode of production, as it had to develop naturally, by following the "economic laws of history."[108] The theory is most notable for allowing capitalists, officially referred to as the "new social strata", to join the party on the grounds that they engaged in "honest labor and work" and through their labour contributed "to build[ing] socialism with Chinese characteristics."[109]

In 2003, the 3rd Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee conceived and formulated the ideology of the Scientific Outlook on Development (SOD).[110] It is considered to be Hu Jintao's contribution to the official ideological discourse.[111] The SOD incorporates scientific socialism, sustainable development, social welfare, a humanistic society, increased democracy, and, ultimately, the creation of a Socialist Harmonious Society. According to official statements by the CCP, the concept integrates "Marxism with the reality of contemporary China and with the underlying features of our times, and it fully embodies the Marxist worldview on and methodology for development."[112]

Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, commonly known as Xi Jinping Thought, was added to the party constitution in the 19th National Congress in 2017.[87] The theory's main elements are summarized in the ten affirmations, the fourteen commitments, and the thirteen areas of achievements.[113]

The party combines elements of both socialist patriotism[114][115][116][117] and Chinese nationalism.[118]

Economics

Deng did not believe that the fundamental difference between the capitalist mode of production and the socialist mode of production was central planning versus free markets. He said, "A planned economy is not the definition of socialism, because there is planning under capitalism; the market economy happens under socialism, too. Planning and market forces are both ways of controlling economic activity".[72] Jiang Zemin supported Deng's thinking, and stated in a party gathering that it did not matter if a certain mechanism was capitalist or socialist, because the only thing that mattered was whether it worked.[76] It was at this gathering that Jiang Zemin introduced the term socialist market economy, which replaced Chen Yun's "planned socialist market economy".[76] In his report to the 14th National Congress Jiang Zemin told the delegates that the socialist state would "let market forces play a basic role in resource allocation."[119] At the 15th National Congress, the party line was changed to "make market forces further play their role in resource allocation"; this line continued until the 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee,[119] when it was amended to "let market forces play a decisive role in resource allocation."[119] Despite this, the 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee upheld the creed "Maintain the dominance of the public sector and strengthen the economic vitality of the state-owned economy."[119]

"... their theory that capitalism is the ultimate [force] has been shaken, and socialist development has experienced a miracle. Western capitalism has suffered reversals, a financial crisis, a credit crisis, a crisis of confidence, and their self-conviction has wavered. Western countries have begun to reflect, and openly or secretively compare themselves against China's politics, economy and path."

— Xi Jinping, on the inevitability of socialism[120]

The CCP views the world as organized into two opposing camps; socialist and capitalist.[121] They insist that socialism, on the basis of historical materialism, will eventually triumph over capitalism.[121] In recent years, when the party has been asked to explain the capitalist globalization occurring, the party has returned to the writings of Karl Marx.[121] Despite admitting that globalization developed through the capitalist system, the party's leaders and theorists argue that globalization is not intrinsically capitalist.[122] The reason being that if globalization was purely capitalist, it would exclude an alternative socialist form of modernity.[122] Globalization, as with the market economy, therefore does not have one specific class character (neither socialist nor capitalist) according to the party.[122] The insistence that globalization is not fixed in nature comes from Deng's insistence that China can pursue socialist modernization by incorporating elements of capitalism.[122] Because of this there is considerable optimism within the CCP that despite the current capitalist dominance of globalization, globalization can be turned into a vehicle supporting socialism.[123]

Analysis and criticism

While foreign analysts generally agree that the CCP has rejected orthodox Marxism–Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought (or at least basic thoughts within orthodox thinking), the CCP itself disagrees.[124] Critics of the CCP argue that Jiang Zemin ended the party's formal commitment to Marxism–Leninism with the introduction of the ideological theory, the Three Represents.[125] However, party theorist Leng Rong disagrees, claiming that "President Jiang rid the Party of the ideological obstacles to different kinds of ownership ... He did not give up Marxism or socialism. He strengthened the Party by providing a modern understanding of Marxism and socialism—which is why we talk about a 'socialist market economy' with Chinese characteristics."[125] The attainment of true "communism" is still described as the CCP's and China's "ultimate goal".[126] While the CCP claims that China is in the primary stage of socialism, party theorists argue that the current development stage "looks a lot like capitalism".[126] Alternatively, certain party theorists argue that "capitalism is the early or first stage of communism."[126] Some have dismissed the concept of a primary stage of socialism as intellectual cynicism.[126] For example, Robert Lawrence Kuhn, a former foreign adviser to the Chinese government, stated: "When I first heard this rationale, I thought it more comic than clever—a wry caricature of hack propagandists leaked by intellectual cynics. But the 100-year horizon comes from serious political theorists."[126]

American political scientist and sinologist David Shambaugh argues that before the "Practice Is the Sole Criterion for the Truth" campaign, the relationship between ideology and decision making was a deductive one, meaning that policy-making was derived from ideological knowledge.[127] However, under Deng's leadership this relationship was turned upside down, with decision making justifying ideology.[127] Chinese policy-makers have described the Soviet Union's state ideology as "rigid, unimaginative, ossified, and disconnected from reality", believing that this was one of the reasons for the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Therefore, Shambaugh argues, Chinese policy-makers believe that their party ideology must be dynamic to safeguard the party's rule.[127]

British sinologist Kerry Brown argues that the CCP does not have an ideology, and that the party organization is pragmatic and interested only in what works.[128] The party itself argues against this assertion. Hu Jintao stated in 2012 that the Western world is "threatening to divide us" and that "the international culture of the West is strong while we are weak ... Ideological and cultural fields are our main targets".[128] As such, the CCP puts a great deal of effort into the party schools and into crafting its ideological message.[128]

Governance

Collective leadership

Collective leadership, the idea that decisions will be taken through consensus, has been the ideal in the CCP.[129] The concept has its origins back to Lenin and the Russian Bolshevik Party.[130] At the level of the central party leadership this means that, for instance, all members of the Politburo Standing Committee are of equal standing (each member having only one vote).[129] A member of the Politburo Standing Committee often represents a sector; during Mao's reign, he controlled the People's Liberation Army, Kang Sheng, the security apparatus, and Zhou Enlai, the State Council and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[129] This counts as informal power.[129] Despite this, in a paradoxical relation, members of a body are ranked hierarchically (despite the fact that members are in theory equal to one another).[129] Informally, the collective leadership is headed by a "leadership core"; that is, the paramount leader, the person who holds the offices of CCP general secretary, CMC chairman and PRC president.[131] Before Jiang Zemin's tenure as paramount leader, the party core and collective leadership were indistinguishable.[132] In practice, the core was not responsible to the collective leadership.[132] However, by the time of Jiang, the party had begun propagating a responsibility system, referring to it in official pronouncements as the "core of the collective leadership".[132] Academics have noted a decline in collective leadership under Xi Jinping.[133][134][135]

Democratic centralism

"[Democratic centralism] is centralized on the basis of democracy and democratic under centralized guidance. This is the only system that can give full expression to democracy with full powers vested in the people's congresses at all levels and, at the same time, guarantee centralized administration with the governments at each level ..."

— Mao Zedong, from his speech entitled "Our General Programme"[136]

The CCP's organizational principle is democratic centralism, a principle that entails open discussion of policy on the condition of unity among party members in upholding the agreed-upon decision.[137] It is based on two principles: democracy (synonymous in official discourse with "socialist democracy" and "inner-party democracy") and centralism.[136] This has been the guiding organizational principle of the party since the 5th National Congress, held in 1927.[136] In the words of the party constitution, "The Party is an integral body organized under its program and constitution and on the basis of democratic centralism".[136] Mao once quipped that democratic centralism was "at once democratic and centralized, with the two seeming opposites of democracy and centralization united in a definite form." Mao claimed that the superiority of democratic centralism lay in its internal contradictions, between democracy and centralism, and freedom and discipline.[136] Currently, the CCP is claiming that "democracy is the lifeline of the Party, the lifeline of socialism".[136] But for democracy to be implemented, and functioning properly, there needs to be centralization.[136] Democracy in any form, the CCP claims, needs centralism, since without centralism there will be no order.[136]

Shuanggui

Shuanggui is an intra-party disciplinary process conducted by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), which conducts shuanggui on members accused of "disciplinary violations", a charge which generally refers to political corruption. The process, which literally translates to "double regulation", aims to extract confessions from members accused of violating party rules. According to the Dui Hua Foundation, tactics such as cigarette burns, beatings and simulated drowning are among those used to extract confessions. Other reported techniques include the use of induced hallucinations, with one subject of this method reporting that "In the end I was so exhausted, I agreed to all the accusations against me even though they were false."[138]

United front

The CCP employs a political strategy that it terms "united front work" that involves groups and key individuals that are influenced or controlled by the CCP and used to advance its interests.[139][140] United front work is managed primarily but not exclusively by the United Front Work Department (UFWD).[141] The united front has historically been a popular front that has included eight legally-permitted political parties alongside other people's organizations which have nominal representation in the National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).[142] However, the CPPCC is a body without real power.[143] While consultation does take place, it is supervised and directed by the CCP.[143] Under Xi Jinping, the united front and its targets of influence have expanded in size and scope.[144][145]

Organization

Central organization

The National Congress is the party's highest body, and, since the 9th National Congress in 1969, has been convened every five years (prior to the 9th Congress they were convened on an irregular basis). According to the party's constitution, a congress may not be postponed except "under extraordinary circumstances."[146] The party constitution gives the National Congress six responsibilities:[147]

- Electing the Central Committee;

- Electing the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI);

- Examining the report of the outgoing Central Committee;

- Examining the report of the outgoing CCDI;

- Discussing and enacting party policies; and,

- Revising the party's constitution.

In practice, the delegates rarely discuss issues at length at the National Congresses. Most substantive discussion takes place before the congress, in the preparation period, among a group of top party leaders.[147] In between National Congresses, the Central Committee is the highest decision-making institution.[148] The CCDI is responsible for supervising party's internal anti-corruption and ethics system.[149] In between congresses the CCDI is under the authority of the Central Committee.[149]

The Central Committee, as the party's highest decision-making institution between national congresses, elects several bodies to carry out its work.[150] The first plenary session of a newly elected central committee elects the general secretary of the Central Committee, the party's leader; the Central Military Commission (CMC); the Politburo; the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). The first plenum also endorses the composition of the Secretariat and the leadership of the CCDI.[150] According to the party constitution, the general secretary must be a member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), and is responsible for convening meetings of the PSC and the Politburo, while also presiding over the work of the Secretariat.[151] The Politburo "exercises the functions and powers of the Central Committee when a plenum is not in session".[152] The PSC is the party's highest decision-making institution when the Politburo, the Central Committee and the National Congress are not in session.[153] It convenes at least once a week.[154] It was established at the 8th National Congress, in 1958, to take over the policy-making role formerly assumed by the Secretariat.[155] The Secretariat is the top implementation body of the Central Committee, and can make decisions within the policy framework established by the Politburo; it is also responsible for supervising the work of organizations that report directly into the Central Committee, for example departments, commissions, publications, and so on.[156] The CMC is the highest decision-making institution on military affairs within the party, and controls the operations of the People's Liberation Army.[157] The general secretary has, since Jiang Zemin, also served as Chairman of the CMC.[157] Unlike the collective leadership ideal of other party organs, the CMC chairman acts as commander-in-chief with full authority to appoint or dismiss top military officers at will.[157]

A first plenum of the Central Committee also elects heads of departments, bureaus, central leading groups and other institutions to pursue its work during a term (a "term" being the period elapsing between national congresses, usually five years).[146] The General Office is the party's "nerve centre", in charge of day-to-day administrative work, including communications, protocol, and setting agendas for meetings.[158] The CCP currently has six main central departments: the Organization Department, responsible for overseeing provincial appointments and vetting cadres for future appointments,[159] the Publicity Department (formerly "Propaganda Department"), which oversees the media and formulates the party line to the media,[160][161] the United Front Work Department, which oversees the country's eight minor parties, people's organizations, and influence groups inside and outside of the country,[162] the International Department, functioning as the party's "foreign affairs ministry" with other parties, the Social Work Department, which handles work related to civic groups, chambers of commerce and industry groups and mixed-ownership and non-public enterprises,[163] and the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, which oversees the country's legal enforcement authorities.[164] The CC also has direct control over the Central Policy Research Office, which is responsible for researching issues of significant interest to the party leadership,[165] the Central Party School, which provides political training and ideological indoctrination in communist thought for high-ranking and rising cadres,[166] the Institute of Party History and Literature, which sets priorities for scholarly research in state-run universities and the Central Party School and studies and translates the classical works of Marxism.[167][168] The party's newspaper, the People's Daily, is under the direct control of the Central Committee[169] and is published with the objectives "to tell good stories about China and the (Party)" and to promote its party leader.[170] The theoretical magazines Qiushi and Study Times are published by the Central Party School.[166] The China Media Group, which oversees China Central Television (CCTV), China National Radio (CNR) and China Radio International (CRI), is under the direct control of the Publicity Department.[171] The various offices of the "Central Leading Groups", such as the Hong Kong and Macau Work Office, the Taiwan Affairs Office, and the Central Finance Office, also report to the central committee during a plenary session.[172] Additionally, CCP has sole control over the People's Liberation Army (PLA) through its Central Military Commission.[173]

Lower-level organizations

After seizing political power, the CCP extended the dual party-state command system to all government institutions, social organizations, and economic entities.[174] The State Council and the Supreme Court each has a party group, established since November 1949. Party committees permeate in every state administrative organ as well as the People's Consultation Conferences and mass organizations at all levels.[175] According to scholar Rush Doshi, "[t]he Party sits above the state, runs parallel to the state, and is enmeshed in every level of the state."[175] Modelled after the Soviet Nomenklatura system, the party committee's organization department at each level has the power to recruit, train, monitor, appoint, and relocate these officials.[176]

Party committees exist at the level of provinces, cities, counties, and neighbourhoods.[177] These committees play a key role in directing local policy by selecting local leaders and assigning critical tasks.[5][178] The Party secretary at each level is more senior than that of the leader of the government, with the CCP standing committee being the main source of power.[178] Party committee members in each level are selected by the leadership in the level above, with provincial leaders selected by the central Organizational Department, and not removable by the local party secretary.[178] Neighborhood committees are generally composed of older volunteers.[179]: 118

CCP committees exist inside of companies, both private and state-owned.[180] A business that has more than three party members is legally required to establish a committee or branch.[181][182] As of 2021, more than half of China's private firms have such organizations.[183] These branches provide places for new member socialization and host morale boosting events for existing members.[184] They also provide mechanisms that help private firm interface with government bodies and learn about policies which relate to their fields.[185] On average, the profitability of private firms with a CCP branch is 12.6 per cent higher than the profitability of private firms.[186]

Within state-owned enterprises, these branches are governing bodies that make important decisions and inculcate CCP ideology in employees.[187] Party committees or branches within companies also provide various benefits to employees.[188] These may include bonuses, interest-free loans, mentorship programs, and free medical and other services for those in need.[188] Enterprises that have party branches generally provide more expansive benefits for employees in the areas of retirement, medical care, unemployment, injury, and birth and fertility.[189] Increasingly, the CCP is requiring private companies to revise their charters to include the role of the party.[181]

Funding

The funding of all CCP organizations mainly comes from state fiscal revenue. Data for the proportion of total CCP organizations' expenditures in total China fiscal revenue is unavailable.[citation needed]

Members

"It is my will to join the Communist Party of China, uphold the Party's program, observe the provisions of the Party constitution, fulfill a Party member's duties, carry out the Party's decisions, strictly observe Party discipline, guard Party secrets, be loyal to the Party, work hard, fight for communism throughout my life, be ready at all times to sacrifice my all for the Party and the people, and never betray the Party."

The CCP reached 99.19 million members at the end of 2023, a net increase of 1.1 million over the previous year.[2][191] It is the second largest political party in the world after India's Bharatiya Janata Party.[192]

To join the CCP, an applicant must go through an approval process.[193] Adults can file applications for membership with their local party branch.[194] A prescreening process, akin to a background check, follows.[194] Next, established party members at the local branch vet applicants' behaviour and political attitudes and may make a formal inquiry to a party branch near the applicants' parents residence to vet family loyalty to communism and the party.[194] In 2014, only 2 million applications were accepted out of some 22 million applicants.[195] Admitted members then spend a year as a probationary member.[190] Probationary members are typically accepted into the party.[196] Members must pay dues regardless of location and, in 2019, the CCP Central Committee issued a rule requiring members abroad to contact CCP cells at home at least once every six months.[197]

In contrast to the past, when emphasis was placed on the applicants' ideological criteria, the current CCP stresses technical and educational qualifications.[190] To become a probationary member, the applicant must take an admission oath before the party flag.[190] The relevant CCP organization is responsible for observing and educating probationary members.[190] Probationary members have duties similar to those of full members, with the exception that they may not vote in party elections nor stand for election.[190] Many join the CCP through the Communist Youth League.[190] Under Jiang Zemin, private entrepreneurs were allowed to become party members.[190]

Membership demographics

As of December 2023, individuals who identify as farmers, herdsmen and fishermen make up 26 million members; members identifying as workers totalled 6.6 million.[195][2] Another group, the "Managing, professional and technical staff in enterprises and public institutions", made up 16.2 million, 11.5 million identified as working in administrative staff and 7.6 million described themselves as party cadres.[198] The CCP systematically recruits white-collar workers over other social groups.[199] By 2023, CCP membership had become more educated, younger, and less blue-collar than previously, with 56.2% of party members having a college degree or above.[191] As of 2022, around 30 to 35 per cent of Chinese entrepreneurs are or have been a party member.[200] At the end of 2023, the CCP stated that it has approximately 7.59 million ethnic minority members or 7.7% of the party.[2]

Status of women

As of 2023, 30.19 million women are CCP members, representing 30.4% of the party.[2] Women in China have low participation rates as political leaders. Women's disadvantage is most evident in their severe underrepresentation in the more powerful political positions.[201] At the top level of decision making, no woman has ever been among the members of the Politburo Standing Committee, while the broader Politburo currently does not have any female members. Just 3 of 27 government ministers are women, and importantly, since 1997, China has fallen to 53rd place from 16th in the world in terms of female representation in the National People's Congress, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union.[202] CCP leaders such as Zhao Ziyang have vigorously opposed the participation of women in the political process.[203] Within the party women face a glass ceiling.[204]

Benefits of membership

A 2019 Binghamton University study found that CCP members gain a 20% wage premium in the market over non-members.[205] A subsequent academic study found that the economic benefit of CCP membership is strongest on those in lower wealth brackets.[205] CCP households also tend to accumulate wealth faster than non-CCP households.[206]

Certain CCP cadres have access to a special supply system for foodstuffs called tegong.[207] CCP leadership cadres have access to a dedicated healthcare system managed by the CCP General Office.[208]

Communist Youth League

The Communist Youth League (CYL) is the CCP's youth wing, and the largest mass organization for youth in China.[209] To join, an applicant has to be between the ages of 14 and 28.[209] It controls and supervises Young Pioneers, a youth organization for children below the age of 14.[209] The organizational structure of CYL is an exact copy of the CCP's; the highest body is the National Congress, followed by the Central Committee, Politburo, and the Politburo Standing Committee.[210] However, the Central Committee (and all central organs) of the CYL work under the guidance of the CCP central leadership.[211] 2021 estimates put the number of CYL members at over 81 million.[212]

Symbols

At the beginning of its history, the CCP did not have a single official standard for the flag, but instead allowed individual party committees to copy the flag of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[213] The Central Politburo decreed the establishment of a sole official flag on 28 April 1942: "The flag of the CPC has the length-to-width proportion of 3:2 with a hammer and sickle in the upper-left corner, and with no five-pointed star. The Political Bureau authorizes the General Office to custom-make a number of standard flags and distribute them to all major organs".[213]

According to People's Daily, "The red color symbolizes revolution; the hammer-and-sickle are tools of workers and peasants, meaning that the Communist Party of China represents the interests of the masses and the people; the yellow color signifies brightness."[213]

Party-to-party relations

The International Department of the Chinese Communist Party is responsible for dialogue with global political parties.[214]

Communist parties

| Part of a series on |

| Communist parties |

|---|

The CCP continues to have relations with non-ruling communist and workers' parties and attends international communist conferences, most notably the International Meeting of Communist and Workers' Parties.[215] While the CCP retains contact with major parties such as the Communist Party of Portugal,[216] the Communist Party of France,[217] the Communist Party of the Russian Federation,[218] the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia,[219] the Communist Party of Brazil,[220] the Communist Party of Greece,[221] the Communist Party of Nepal[222] and the Communist Party of Spain,[223] the party also retains relations with minor communist and workers' parties, such as the Communist Party of Australia,[224] the Workers Party of Bangladesh, the Communist Party of Bangladesh (Marxist–Leninist) (Barua), the Communist Party of Sri Lanka, the Workers' Party of Belgium, the Hungarian Workers' Party, the Dominican Workers' Party, the Nepal Workers Peasants Party, and the Party for the Transformation of Honduras, for instance.[225] It has prickly[vague] relations with the Japanese Communist Party.[226] In recent years, noting the self-reform of the European social democratic movement in the 1980s and 1990s, the CCP "has noted the increased marginalization of West European communist parties."[227]

Ruling parties of socialist states

The CCP has retained close relations with the ruling parties of socialist states still espousing communism: Cuba, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam.[228] It spends a fair amount of time analysing the situation in the remaining socialist states, trying to reach conclusions as to why these states survived when so many did not, following the collapse of the Eastern European socialist states in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[229] In general, the analyses of the remaining socialist states and their chances of survival have been positive, and the CCP believes that the socialist movement will be revitalized sometime in the future.[229]

The ruling party which the CCP is most interested in is the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV).[230] In general the CPV is considered a model example of socialist development in the post-Soviet era.[230] Chinese analysts on Vietnam believe that the introduction of the Đổi Mới reform policy at the 6th CPV National Congress is the key reason for Vietnam's current success.[230]

While the CCP is probably the organization with most access to North Korea, writing about North Korea is tightly circumscribed.[229] The few reports accessible to the general public are those about North Korean economic reforms.[229] While Chinese analysts of North Korea tend to speak positively of North Korea in public, in official discussions c. 2008 they show much disdain for North Korea's economic system, the cult of personality which pervades society, the Kim family, the idea of hereditary succession in a socialist state, the security state, the use of scarce resources on the Korean People's Army and the general impoverishment of the North Korean people.[231] Circa 2008, there are those analysts who compare the current situation of North Korea with that of China during the Cultural Revolution.[232][needs update] Over the years, the CCP has tried to persuade the Workers' Party of Korea (or WPK, North Korea's ruling party) to introduce economic reforms by showing them key economic infrastructure in China.[232] For instance, in 2006 the CCP invited then-WPK general secretary Kim Jong Il to Guangdong to showcase the success economic reforms had brought China.[232] In general, the CCP considers the WPK and North Korea to be negative examples of a ruling communist party and socialist state.[232]

There is a considerable degree of interest in Cuba within the CCP.[230] Fidel Castro, the former First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), is greatly admired, and books have been written focusing on the successes of the Cuban Revolution.[230] Communication between the CCP and the PCC has increased since the 1990s.[233] At the 4th Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee, which discussed the possibility of the CCP learning from other ruling parties, praise was heaped on the PCC.[233] When Wu Guanzheng, a Central Politburo member, met with Fidel Castro in 2007, he gave him a personal letter written by Hu Jintao: "Facts have shown that China and Cuba are trustworthy good friends, good comrades, and good brothers who treat each other with sincerity. The two countries' friendship has withstood the test of a changeable international situation, and the friendship has been further strengthened and consolidated."[234]

Non-communist parties

Since the decline and fall of communism in Eastern Europe, the CCP has begun establishing party-to-party relations with non-communist parties.[162] These relations are sought so that the CCP can learn from them.[235] For instance, the CCP has been eager to understand how the People's Action Party of Singapore (PAP) maintains its total domination over Singaporean politics through its "low-key presence, but total control."[236] According to the CCP's own analysis of Singapore, the PAP's dominance can be explained by its "well-developed social network, which controls constituencies effectively by extending its tentacles deeply into society through branches of government and party-controlled groups."[236] While the CCP accepts that Singapore is a liberal democracy, they view it as a guided democracy led by the PAP.[236] Other differences are, according to the CCP, "that it is not a political party based on the working class—instead it is a political party of the elite. ... It is also a political party of the parliamentary system, not a revolutionary party."[237] Other parties which the CCP studies and maintains strong party-to-party relations with are the United Malays National Organization, which has ruled Malaysia (1957–2018, 2020–2022), and the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, which dominated Japanese politics since 1955.[238]

Since Jiang Zemin's time, the CCP has made friendly overtures to its erstwhile foe, the Kuomintang. The CCP emphasizes strong party-to-party relations with the KMT so as to strengthen the probability of the reunification of Taiwan with mainland China.[239] However, several studies have been written on the KMT's loss of power in 2000 after having ruled Taiwan since 1949 (the KMT officially ruled mainland China from 1928 to 1949).[239] In general, one-party states or dominant-party states are of special interest to the party and party-to-party relations are formed so that the CCP can study them.[239] The longevity of the Syrian Regional Branch of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party is attributed to the personalization of power in the al-Assad family, the strong presidential system, the inheritance of power, which passed from Hafez al-Assad to his son Bashar al-Assad, and the role given to the Syrian military in politics.[240]

Circa 2008, the CCP has been especially interested in Latin America,[240] as shown by the increasing number of delegates sent to and received from these countries.[240] Of special fascination for the CCP is the 71-year-long rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Mexico.[240] While the CCP attributed the PRI's long reign in power to the strong presidential system, tapping into the machismo culture of the country, its nationalist posture, its close identification with the rural populace and the implementation of nationalization alongside the marketization of the economy,[240] the CCP concluded that the PRI failed because of the lack of inner-party democracy, its pursuit of social democracy, its rigid party structures that could not be reformed, its political corruption, the pressure of globalization, and American interference in Mexican politics.[240] While the CCP was slow to recognize the pink tide in Latin America, it has strengthened party-to-party relations with several socialist and anti-American political parties over the years.[241] The CCP has occasionally expressed some irritation over Hugo Chávez's anti-capitalist and anti-American rhetoric.[241] Despite this, the CCP reached an agreement in 2013 with the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), which was founded by Chávez, for the CCP to educate PSUV cadres in political and social fields.[242] By 2008, the CCP claimed to have established relations with 99 political parties in 29 Latin American countries.[241]

Social democratic movements in Europe have been of great interest to the CCP since the early 1980s.[241] With the exception of a short period in which the CCP forged party-to-party relations with far-right parties during the 1970s in an effort to halt "Soviet expansionism", the CCP's relations with European social democratic parties were its first serious efforts to establish cordial party-to-party relations with non-communist parties.[241] The CCP credits the European social democrats with creating a "capitalism with a human face".[241] Before the 1980s, the CCP had a highly negative and dismissive view of social democracy, a view dating back to the Second International and the Marxist–Leninist view on the social democratic movement.[241] By the 1980s, that view had changed and the CCP concluded that it could actually learn something from the social democratic movement.[241] CCP delegates were sent all over Europe to observe.[243] By the 1980s, most European social democratic parties were facing electoral decline and in a period of self-reform.[243] The CCP followed this with great interest, laying most weight on reform efforts within the British Labour Party and the Social Democratic Party of Germany.[243] The CCP concluded that both parties were re-elected because they modernized, replacing traditional state socialist tenets with new ones supporting privatization, shedding the belief in big government, conceiving a new view of the welfare state, changing their negative views of the market and moving from their traditional support base of trade unions to entrepreneurs, the young and students.[244]

Electoral history

National People's Congress elections

| Election | General Secretary | Seats | +/– | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982–1983 | Hu Yaobang | 1,861 / 2,978

|

||

| 1987–1988 | Zhao Ziyang | 1,986 / 2,979

|

||

| 1993–1994 | Jiang Zemin | 2,037 / 2,979

|

||

| 1997–1998 | 2,130 / 2,979

|

|||

| 2002–2003 | Hu Jintao | 2,178 / 2,985

|

||

| 2007–2008 | 2,099 / 2,987

|

|||

| 2012–2013 | Xi Jinping | 2,157 / 2,987

|

||

| 2017–2018 | 2,119 / 2,980

|

|||

| 2022–2023 |

See also

Notes

- ^ During the Chinese Civil War, party officials were only able to confirm from available documents that the 1st National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party was held in July 1921, but not the specific date of the meeting. In June 1941, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party declared 1 July the party's "anniversary day". Although the exact date of the 1st National Congress was later determined by party officials to be 23 July 1921, the date of the anniversary has not been changed.[1][better source needed]

- ^ Chinese: 为人民服务; pinyin: Wèi Rénmín Fúwù

- ^ Chiang Kai-shek strongly opposed this label and the CCP's analysis of the KMT. He believed that the KMT served all Chinese, regardless of political leanings.[27]

- ^ "In the next weeks five thousand Communists were butchered by the stammering machine-guns of the Kuomintang and by the knives of the criminal gangs whom Chiang recruited for slaughter."[38]

Other sources give different estimates, e.g. 5,000–10,000.[39]

References

Citations

- ^ 楊立傑 (30 April 2013). "共产主义小组的建立与中国共产党的成立". Xinhua (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "中国共产党党内统计公报" [Communist Party of China Party Statistics Announcement] (in Chinese). State Council of the People's Republic of China. 30 June 2024. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ "Chinese Communist Party". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Style Guide: PRC, China, CCP or Chinese?". Asia Media Centre – New Zealand. Asia New Zealand Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

Chinese Communist Party (CCP): May also refer to Communist Party of China (CPC) ... CPC is used officially in China and by China's media, whereas English-language media outside of Chinese conventionally use CCP.

- ^ a b McGregor, Richard (2010). The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0061708770. OCLC 630262666.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Michael (2013). The World Transformed: 1945 to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0312245832.

- ^ Van de Ven 1991, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Hammond, Ken (2023). China's Revolution and the Quest for a Socialist Future. New York, NY: 1804 Books. ISBN 978-1-7368500-8-4.

- ^ a b c Huang, Yibing (2020). Zheng, Qian (ed.). An Ideological History of the Communist Party of China. Vol. 2. Translated by Sun, Li; Bryant, Shelly. Montreal, Quebec: Royal Collins Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4878-0391-9.

- ^ Hao, Zhidong (March 1997). "May 4th and June 4th compared: A sociological study of Chinese social movements". Journal of Contemporary China. 6 (14): 79–99. doi:10.1080/10670569708724266. ISSN 1067-0564.

- ^ Šebok, Filip (2023). "Historical Legacy". In Kironska, Kristina; Turscanyi, Richard Q. (eds.). Contemporary China: a New Superpower?. Routledge. pp. 15–28. doi:10.4324/9781003350064-3. ISBN 978-1-03-239508-1.

- ^ Van de Ven 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Van de Ven 1991, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the Twentieth-Century World: a Concise History. Asia-pacific: Culture, Politics, and Society series. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11hpp6w. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. JSTOR j.ctv11hpp6w.

- ^ Hé, Lìbō. "Xiǎn wéi rénzhī de zhōnggòng yī dà cānjiāzhě: Éguórén Níkē'ěrsījī" 鲜为人知的中共一大参加者:俄国人尼科尔斯基. People's Daily 中国共产党新闻网 [News of the Communist Party of China] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Party History Research Office of the CPC Central Committee (1997). 共產國際、聯共(布)與中國革命檔案資料叢書. Beijing Library Press. pp. 39–51.

- ^ Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (20 July 2011). "On Party Anniversary, China Rewrites History". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "1st. National Congress of The Communist Party of China (CPC)". Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ "Three Chinese Leaders: Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping". Asia for Educators. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Gao 2009, p. 119.

- ^ "News of the Soviets of People's Deputies". 9 October 1920.

- ^ "News of the Soviets of People's Deputies". 16 November 1921.

- ^ 中央檔案館 (1989). 中共中央文件選集1. 中共中央黨校出版社. pp. 187, 271–297.

- ^ 中共中央、共青團中央和共產國際代表聯席會議記錄. December 1924.

- ^ 共產國際有關中國資料選輯 Collection of the Communist International's Materials on China. Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. 1981. p. 83.

- ^ a b c Schram 1966, pp. 84, 89.

- ^ a b Chiang, Chung Cheng (1957). Soviet Russia in China: a Summing Up at Seventy. Farrar, Straus and Cudahy. OL 89083W.

- ^ 奎松, 楊 (April 2010). 中間地帶的革命. Taiyuan: 山西人民出版社.

- ^ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany. "The Chinese Communist Party Is Still Afraid of Sun Yat-Sen's Shadow". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Tug of war over China's founding father Sun Yat-sen as Communist Party celebrates his legacy". South China Morning Post. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Dirlik 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Godley, Michael R. (1987). "Socialism with Chinese Characteristics: Sun Yatsen and the International Development of China". The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs (18): 109–125. doi:10.2307/2158585. JSTOR 2158585. S2CID 155947428.

- ^ 獨秀, Du Xiu (3 April 1926). "中國革命勢力統一政策與廣州事變". 嚮導.

- ^ 中央檔案館 (1989). 中共中央文件選集2. 中共中央黨校出版社. pp. 311–318.

- ^ 奎松, 楊 (2002). "蔣介石從三二零到四一二的心路歷程". 史學月刊. 6.

- ^ 上海市檔案館 (1983). 上海工人三次武裝起義. 上海人民出版社.

- ^ a b Feigon 2002, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Carter 1976, p. 62.

- ^ Ryan, Tom (2016). Purnell, Ingrid; Plozza, Shivaun (eds.). China Rising: The Revolutionary Experience. Collingwood: History Teachers' Association of Victoria. p. 77. ISBN 978-1875585083.

- ^ Schram 1966, p. 106.

- ^ Carter 1976, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Schram 1966, p. 112.

- ^ Schram 1966, pp. 106–109.

- ^ Schram 1966, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Carter 1976, p. 63.

- ^ a b Carter 1976, p. 64.

- ^ Schram 1966, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Feigon 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Leung 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Duan, Lei (2024). "Towards a More Joint Strategy: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms and Militia Reconstruction". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.). China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment. Leiden University Press. ISBN 9789087284411.

- ^ Leung 1992, p. 370.

- ^ a b Leung 1992, p. 354.

- ^ a b c d e Leung 1992, p. 355.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Leung 1992, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d Leung 1992, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Leung 1996, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f Miller, Alice. "The 19th Central Committee Politburo" (PDF). China Leadership Monitor, No. 55. Hoover Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ 哲, 師 (1991). 在歷史巨人身邊——師哲回憶錄. Beijing: 中央文獻出版社. p. 531.

- ^ 子陵, 辛 (2009). 紅太陽的隕落:千秋功罪毛澤東. Hong Kong: 書作坊. p. 88.

- ^ 理羣, 錢 (2012). 毛澤東和後毛澤東時代. Taipei: 聯經. p. 64.

- ^ King, Gilbert. "The Silence that Preceded China's Great Leap into Famine". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Du, Guang (2007). ""反右"运动与民主革命——纪念"反右"运动五十周年". Modern China Studies (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Gráda, Cormac Ó (2007). "Making Famine History" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 45 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1257/jel.45.1.5. hdl:10197/492. ISSN 0022-0515. JSTOR 27646746. S2CID 54763671. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Meng, Xin; Qian, Nancy; Yared, Pierre (2015). "The Institutional Causes of China's Great Famine, 1959–1961" (PDF). The Review of Economic Studies. 82 (4): 1568–1611. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.321.1333. doi:10.1093/restud/rdv016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (18 December 1999). "China's great famine: 40 years later". The BMJ. 319 (7225): 1619–1621. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1127087. PMID 10600969.

- ^ Mirsky, Jonathan (7 December 2012). "Unnatural Disaster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Dikötter, Frank. "Mao's Great Famine: Ways of Living, Ways of Dying" (PDF). Dartmouth College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2020.

- ^ Kornberg & Faust 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Wong 2005, p. 131.

- ^ a b Wong 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Sullivan 2012, p. 254.

- ^ a b Deng Xiaoping (30 June 1984). "Building a Socialism with a specifically Chinese character". People's Daily. Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "An article influences Chinese history". China Internet Information Center. 19 January 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Doyon, Jérôme; Froissart, Chloé (2024). "Introduction". In Doyon, Jérôme; Froissart, Chloé (eds.). The Chinese Communist Party: a 100-Year Trajectory. Canberra: ANU Press. ISBN 9781760466244.

- ^ Sullivan 2012, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Vogel 2011, p. 682.

- ^ a b c Vogel 2011, p. 684.

- ^ Sullivan 2012, p. 100.

- ^ a b Sullivan 2012, p. 238.

- ^ a b Sullivan 2012, p. 317.

- ^ Sullivan 2012, p. 329.

- ^ "Hu Jintao, Xi Jinping meet delegates to 18th CCP National Congress". Xinhua News Agency. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ O’Keeffe, Kate; Ferek, Katy Stech (14 November 2019). "Stop Calling China's Xi Jinping 'President,' U.S. Panel Says". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "The Rise and Rise of Xi Jinping: Xi who must be obeyed". The Economist. 20 September 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.