Histopathology image classification: Highlighting the gap between manual analysis and AI automation

Contents

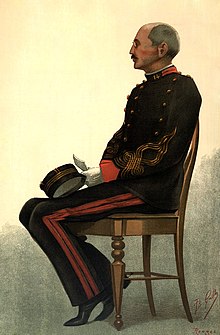

Alfred Dreyfus | |

|---|---|

Dreyfus c. 1894 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 October 1859[1] Mulhouse, French Empire |

| Died | 12 July 1935 (aged 75) Paris, French Republic |

| Resting place | Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris 48°50′17″N 2°19′37″E / 48.83806°N 2.32694°E |

| Nationality | French[1] |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Pierre Dreyfus Jeanne Dreyfus Levy |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique École Supérieure de Guerre |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | French Army |

| Years of service | 1880–1918 |

| Rank | |

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Alfred Dreyfus (French: [alfʁɛd dʁɛfys], German: [ˈalfʁeːt ˈdʁaɪfuːs]; 9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French artillery officer of Alsatian origin and Jewish ethnicity and faith. In 1894, he fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that sparked a major political crisis during the Third Republic, known as the Dreyfus Affair (1894–1906), when he was wrongfully accused and convicted, due to antisemitism, of being a spy for the German Empire. Upon his arrest, he was sentenced to degradation and deported to the penal colony on Devil's Island to be imprisoned until his death. However, evidence emerged showing that Dreyfus was innocent and that the true culprit was a Catholic officer named Esterhazy. Gradual revelations indicated that the internal investigation conducted by the army was biased; Dreyfus was an ideal scapegoat because he was Jewish, and the army's high command was aware of his innocence but preferred to cover up the affair and leave him in the penal colony rather than lose face.

The scandal erupted, shaking French political life; it highlighted the connections between the French army and the political circles of the time with antisemitism. After numerous judicial and political twists, the publication of Émile Zola's manifesto, J'accuse... !, in 1898 brought new momentum to Dreyfus's cause. Zola accused the army and French political leaders of covering up the affair. Dreyfus was eventually exonerated, rehabilitated, and reinstated in the French army, although at a lower rank than his seniority would have warranted.

The anti-Dreyfusard and antisemitic factions, however, viewed this rehabilitation unfavorably, and while attending the transfer of Émile Zola's remains to the Panthéon, Dreyfus was targeted in an attack by an antisemitic militarist activist, who was later acquitted in trial, but Dreyfus survived.

He fought in World War I, notably at Verdun and the Chemin des Dames, then retired and led a quiet life. He died in 1935 in Paris and was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery.

Alfred Dreyfus's life and the persecutions he endured because he was Jewish left a significant mark on French political consciousness; the true culprit, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, remained unpunished. Among Dreyfus’s defenders were writers such as Émile Zola, Charles Péguy, and Anatole France, politicians like Georges Clemenceau and Jean Jaurès, and the founders of the Human Rights League (LDH) Francis de Pressensé and Pierre Quillard.

Early life, family, and education

Born in Mulhouse, Alsace in 1859, to Raphaël and Jeannette Dreyfus (née Libmann), the youngest of nine children (seven of whom survived to adulthood).[2] His grandfather was a merchant from a long established Alsatian Jewish family in Rixheim, not far from Mulhouse. His father became a prosperous industrialist who started a cotton mill, then expanded the business with a weaving factory. This enabled the Dreyfus family to live a comfortable and affluent life within Mulhouse society. He spent his first years in a house on Rue du Sauvage, then later in a mansion on Rue de la Sinne, both in Mulhouse.

Because of his mother's bedridden illness following his birth, his sister Henriette became like a second mother to him. Alfred was 10 years old when the Franco-Prussian War broke out in the summer of 1870, and following the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany after the war, he and his family moved to Basel, Switzerland, where he attended high school. The family later relocated to Paris.

Early career

The childhood experience of seeing his family uprooted by the war with Germany prompted Dreyfus to decide on a career in the military. Following his 18th birthday in October 1877, he enrolled in the elite École Polytechnique military school in Paris, where he received military training and an education in the sciences. In 1880, he graduated and was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant in the French army. From 1880 to 1882, he attended the artillery school at Fontainebleau to receive more specialized training as an artillery officer. On graduation, he was assigned to the 31st Artillery Regiment, which was in the garrison at Le Mans. Dreyfus was subsequently transferred to a mounted artillery battery attached to the First Cavalry Division (Paris), and promoted to lieutenant in 1885. In 1889, he was made adjutant to the director of the Établissement de Bourges, a government arsenal, and promoted to captain.[2]

On 18 April 1891, the 31-year-old Dreyfus married 20-year-old Lucie Eugénie Hadamard (1870–1945). They had two children, Pierre (1891–1946) and Jeanne (1893–1981).[2] Three days after the wedding, Dreyfus learned that he had been admitted to the École Supérieure de Guerre or War College. Two years later, he graduated ninth in his class with honourable mention and was immediately designated as a trainee in the French Army's General Staff headquarters, where he would be the only Jewish officer. His father Raphaël died on 13 December 1893.

At the War College examination in 1892, his friends had expected him to do well. However, one of the members of the panel, General Bonnefond, felt that "Jews were not desired" on the staff, and gave Dreyfus poor marks for cote d'amour (French slang: attraction; translatable as likability). Bonnefond's assessment lowered Dreyfus' overall grade; he did the same to another Jewish candidate, Lieutenant Picard. Learning of this injustice, the two officers lodged a protest with the director of the school, General Lebelin de Dionne, who expressed his regret for what had occurred, but said he was powerless to take any steps in the matter. The protest would later count against Dreyfus. The French army of the period was relatively open to entry and advancement by talent, with an estimated 300 Jewish officers, of whom ten were generals.[3]: 83 However, within the Fourth Bureau of the General Staff, General Bonnefond's prejudices appear to have been shared by some of the new trainee's superiors. The personal assessments received by Dreyfus during 1893/94 acknowledged his high intelligence, but were critical of aspects of his personality.[3]: 84

The Dreyfus affair

| Part of a series on the |

| Dreyfus affair |

|---|

|

A torn-up handwritten note, referred to throughout the affair as the bordereau, was found by a French housekeeper, a woman named Marie Bastian, in a wastebasket at the German Embassy. Bastian, whose job was to burn the waste of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, instead sent it to Hubert-Joseph Henry for potential interest to French intelligence.[4] The bordereau described a minor French military secret, and had obviously been written by a spy in the French military.

In 1894, this made the French Army's counter-intelligence section, led by Lieutenant Colonel Jean Sandherr, aware that information regarding new artillery parts was being passed to Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attache in Paris, by a highly placed spy most likely on the General Staff. Suspicion quickly fell upon Dreyfus, who was arrested for treason on 15 October 1894.

On 5 January 1895, Dreyfus was summarily convicted in a secret court martial, publicly stripped of his army rank, and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island in French Guiana. Following French military custom of the time, Dreyfus was formally degraded (cashiered) by having the rank insignia, buttons and braid cut from his uniform and his sword broken, all in the courtyard of the École Militaire before silent ranks of soldiers, while a large crowd of onlookers shouted abuse from behind railings. Dreyfus cried out: "I swear that I am innocent. I remain worthy of serving in the Army. Long live France! Long live the Army!"[3]: 113

In August 1896, the new chief of French military intelligence, Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart, reported to his superiors that he had found evidence to the effect that the real traitor was the Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. Picquart was silenced by being transferred to command a tirailleur regiment based in Sousse, Tunisia, in November 1896. When reports of an army cover-up and Dreyfus' possible innocence were leaked to the press, a heated debate ensued about antisemitism and France's identity as a Catholic nation or a republic founded on equal rights for all citizens.

Esterhazy was found not guilty by a secret court martial, before fleeing secretly to England and shaving off his moustache. Rachel Beer, editor of The Observer and the Sunday Times, interviewed him twice. He confessed to writing the bordereau under orders from Sandherr in an attempt to frame Dreyfus. She wrote about her interviews in September 1898,[5] reporting his confession and writing a leader column accusing the French military of antisemitism and calling for a retrial for Dreyfus.[6]

In France there was a passionate campaign by Dreyfus' supporters, including leading artists and intellectuals such as Émile Zola,[7] following which he was given a second trial in 1899, but again declared guilty of treason despite the evidence of his innocence.

However, due to public opinion, Dreyfus was offered and accepted a pardon by President Émile Loubet in 1899 and released from prison; this was a compromise that saved face for the military's mistake. Had Dreyfus refused the pardon, he would have been returned to Devil's Island, a fate he could no longer emotionally cope with; so officially Dreyfus remained a traitor to France, and pointedly remarked upon his release:

The government of the Republic has given me back my freedom. It is nothing for me without my honour.[2]

For two years, until July 1906, he lived in a state of house arrest with one of his sisters at Carpentras, and later at Cologny.

On 12 July 1906, Dreyfus was officially exonerated by a military commission. The day after his exoneration, he was readmitted into the army with a promotion to the rank of major (Chef d'Escadron). A week later, he was made Knight of the Legion of Honour,[8] and subsequently assigned to command an artillery unit at Vincennes. On 15 October 1906, he was placed in command of another artillery unit at Saint-Denis.

Aftermath

While attending a ceremony relocating Zola's ashes to the Panthéon on 4 June 1908, Dreyfus was wounded in the arm by a gunshot from a right-wing journalist, Louis Grégori, who was trying to assassinate him. Grégori was acquitted by the Parisian court, which accepted his defence that he had not meant to kill Dreyfus, meaning merely to graze him.[9]

In 1937, Dreyfus' son Pierre published his father's memoirs based on his correspondence between 1899 and 1906. The memoirs were titled Souvenirs et Correspondance and translated into English by Betty Morgan.[10]

Dreyfus started corresponding with the marquise Marie-Louise Arconati-Visconti in 1899 and began attending her Thursday (political) salons after his release. They continued their correspondence until her death in 1923.[11]

Modern aftermath

In October 2021, French president Emmanuel Macron opened a museum dedicated to the Dreyfus affair in Médan in the northwestern suburbs of Paris. He said that nothing could repair the humiliations and injustices Dreyfus had suffered, and "let us not aggravate it by forgetting, deepening, or repeating them".[12]

The reference to not repeating them follows attempts by the French far right to question Dreyfus' innocence. An army colonel was cashiered in 1994 for publishing an article suggesting that Dreyfus was guilty; far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen's lawyer responded that Dreyfus' exoneration was "contrary to all known jurisprudence". Éric Zemmour, a far-right political opponent of Macron, said repeatedly in 2021 that the truth about Dreyfus was not clear; his innocence was "not obvious".[12]

Later life

World War I

Dreyfus' prison sentence on Devil's Island had taken its toll on his health. He was granted retirement from the army in October 1907 at the age of 48. As a reserve officer, he re-entered the army as a major of artillery at the outbreak of World War I. Serving throughout the war, Dreyfus was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

By then in his mid-50s, Dreyfus served mostly behind the lines of the Western Front, in part as commander of an artillery supply column. However, he also performed front-line duties in 1917, notably at Verdun and on the Chemin des Dames. He was promoted to Officer of the Legion of Honour in November 1918.[13]

Dreyfus' son Pierre also served throughout the entire war as an artillery officer, receiving the Croix de guerre.

Death

Dreyfus died in Paris aged 75, on 12 July 1935. Two days later, his funeral cortège passed the Place de la Concorde through the ranks of troops assembled for the Bastille Day national holiday. He was interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris.

A statue of Dreyfus holding his broken sword is located at Boulevard Raspail, nº116–118, at the exit of the Notre-Dame-des-Champs metro station. A duplicate statue stands in the courtyard of the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris.

During the German occupation of France during WWII, Lucie Dreyfus, who had played a major role in the fight to exonerate her husband, was hidden in a convent in Valence. Their son, Pierre Léon Dreyfus (1891–1946), escaped to the United States in 1943. Their daughter, Jeanne Dreyfus Lévy (1893–1981), also survived, but granddaughter Madeleine Levy, arrested by French police in Toulouse, was deported and died of typhus in Auschwitz in January 1944, aged 25.[3]: 352

Legacy

Dreyfus' grandchildren donated over three thousand documents to the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme (Museum of Jewish Art and History), including personal letters, photographs of the trial, legal documents, writings by Dreyfus during his time in prison, personal family photographs, and his officer stripes that had been ripped off as a symbol of treason. The museum created an online platform in 2006 dedicated to the Dreyfus Affair.[14]

Military ranks

| Ranks attained in the French Army | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student | Sous-lieutenant | Lieutenant | Capitaine | Chef d'escadrons | Lieutenant-colonel |

| 1 October 1878[15] | 4 October 1880[15] | 1 November 1882[15] | 12 September 1889[15] | 13 July 1906[15] | 26 September 1918[15] |

Honours and decorations

National honours

| Ribbon bar | Honour |

|---|---|

| Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honour – 21 July 1906[16] | |

| Officer of the National Order of the Legion of Honour – 21 January 1919[17] |

Decorations and medals

| Ribbon bar | Honour |

|---|---|

| War Cross 1914–1918 | |

| 1914–1918 Commemorative war medal |

See also

- Florence Earle Coates, a Philadelphia poet, wrote four poems about the Dreyfus affair: two entitled "Dreyfus", one published in 1898 and the other in 1899, "Picquart" (1902), and "Le Grand Salut" (1906)

- Jack Dreyfus, founder of the Dreyfus Funds and relative

- Gérard Louis-Dreyfus, American businessman and distant relative

- Julia Louis-Dreyfus, American actress and distant relative

- J'Accuse…!, influential 1898 open letter written by Émile Zola

- Theodor Herzl, Austrian journalist who began the Zionist movement after seeing the antisemitism present in Dreyfus' trial

- Gaston Moch, a defense supporter of Dreyfus

- Charles Péguy, who wrote a defense of Dreyfus

- George Whyte, an authority on the Dreyfus affair who has authored a large body of literary and stage works on Dreyfus and the Dreyfus affair

- Julie Dreyfus, French actress and descendant

- The Dreyfus Affair (film series), an 1899 series of short silent docudramas

- The Prisoner of the Devil, a novel by Michael Hardwick which features Sherlock Holmes called in to solve the case

- An Officer and a Spy, a novel written in first person by Robert Harris, in the form of an account of the Dreyfus Affair as if written by Georges Picquart

- The Life of Emile Zola, a 1937 film starring Joseph Schildkraut as Dreyfus, who won best actor in a supporting role at the Academy Awards

- I Accuse!, a 1958 film starring José Ferrer as Dreyfus

- An Officer and a Spy, film by Roman Polanski (2019)

References

- ^ a b "Birth certificate of Dreyfus, Alfred". culture.gouv.fr. Government of the French Republic. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Alfred Dreyfus". YuMuseum.org. Yeshiva University Museum. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d Read, Piers Paul (2012). The Dreyfus Affair. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-4088-3057-4.

- ^ "Dreyfus Affair Court-Martial (1894)". www.famous-trials.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Beer, Rachel. "Light Upon the Dreyfus Case. Major Esterhazy in London." (18 September), "The Esterhazy Revelations." (25 September). The Observer, 1898.

- ^ Narewska, Elli (2 March 2018). "Rachel Beer, editor of the Observer 1891–1901". The Guardian.

- ^ "Summary of Emile Zola's J'Accuse, and its Repercussions. Dreyfus Letter to Zola's Widow, 1910". SMF Primary Sources. Shapell Manuscript Foundation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "Minutes of the induction of Dreyfus into the Legion of Honour, French Ministry of Culture and Communication". dreyfus.cultur.fr. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011.

- ^ Valier, C. (2005). Crime and Punishment in Contemporary Culture. International Library of Sociology. Taylor & Francis. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-134-46105-9.

- ^ Dreyfus, Pierre (1937). Souvenirs Et Correspondance. Dreyfus: His Life and Letters. Translated by Morgan, Betty. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) French original Archived 30 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Wood, Michael (17 September 2017). "The French Are Not Men". London Review of Books. 39 (17). Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017. (London Review of Books)

- ^ a b Henley, Jon (30 October 2021). "Rise of far right puts Dreyfus affair into spotlight in French election race". The Observer.

- ^ Biography of Alfred Dreyfus and General Chronology Archived 13 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, French Ministry of Culture and Communication

- ^ "Affaire Dreyfus, Paris, France, | Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme". 29 May 2017. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Service records of Dreyfus, Alfred". culture.gouv.fr. Government of the French Republic. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Legion of honour certificate (Knight) of Dreyfus, Alfred". culture.gouv.fr. Government of the French Republic. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Legion of honour certificate (Officer) of Dreyfus, Alfred". culture.gouv.fr. Government of the French Republic. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

- Burns, Michael (1991). Dreyfus: A Family Affair, 1789–1945. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-016366-2.

- Samuels, Maurice (2024). Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25400-6.

Primary sources

- Lettres d'un innocent [Letters from an innocent man] (in French). 1898.

- Letters from Captain Dreyfus to his wife (in French). 1899. – written at Devil's Island

- Cinq années de ma vie (in French). 1901.

- Five years of my life. Comino. 2019. ISBN 978-3-945831-19-9. – translation of Cinq années de ma vie

- Souvenirs et correspondence. 1936. – published posthumously

External links

- Works by Alfred Dreyfus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Alfred Dreyfus at the Internet Archive

- Works by Alfred Dreyfus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Dreyfus Rehabilitated Archived 19 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- References to Alfred Dreyfus in European newspapers of the time – The European Library

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Alfred Dreyfus Personal Manuscripts and Letters

- Online platform on Musée d'art et d'histoire du judaïsme site

- Newspaper clippings about Alfred Dreyfus in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Actors and scenes in the drama of disgrace, A booklet with nearly one hundred photographs and documents from the arrest and trial of Dreyfus, from the National Library of Israel