FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

| |

| Location | 111 South Grand Avenue Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°03′19″N 118°15′00″W / 34.05528°N 118.25000°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Los Angeles Music Center |

| Type | Concert hall |

| Seating type | Reserved |

| Capacity | 2,265 |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1999–2003 |

| Opened | October 23, 2003 |

| Construction cost | $130 million (plus $110 million for parking garage) |

| Architect | Frank Gehry |

| Structural engineer | John A. Martin & Associates Cosentini Associates[1] |

| Tenants | |

| Los Angeles Philharmonic Los Angeles Master Chorale | |

| Website | |

| Venue website | |

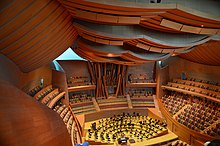

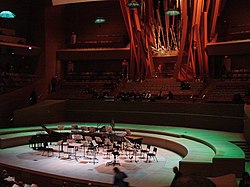

The Walt Disney Concert Hall at 111 South Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles, California, is the fourth hall of the Los Angeles Music Center and was designed by Frank Gehry. It was opened on October 23, 2003. Bounded by Hope Street, Grand Avenue, and 1st and 2nd Streets, it seats 2,265 people and serves, among other purposes, as the home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic orchestra and the Los Angeles Master Chorale. The hall is a compromise between a vineyard-style seating configuration, like the Berliner Philharmonie by Hans Scharoun,[2] and a classical shoebox design like the Vienna Musikverein or the Boston Symphony Hall.[3]

Lillian Disney made an initial gift of $50 million in 1987 to build a performance venue as a gift to the people of Los Angeles and a tribute to Walt Disney's devotion to the arts and to the city. Both Gehry's architecture and the acoustics of the concert hall, designed by Minoru Nagata,[4] the final completion supervised by Nagata's assistant and protege Yasuhisa Toyota,[5] have been praised, in contrast to its predecessor, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.[6]

Design

The Walt Disney Concert Hall was designed by world-renowned architect Frank Gehry. Despite being a well-accomplished architect at the time of design, Gehry found himself an unlikely candidate for the job when the Disney family was looking for the hall's designer. Even with the location of the Walt Disney Concert Hall set to be in his hometown of Los Angeles, California, Gehry, when discussing his thoughts at the time the architect was selected, said, "it was the least likely thing that I thought would ever happen to me in my life".[7] Gehry's opinion was supported by the representative of the Disney family. Gehry says he was told, "that under no circumstances would Walt Disney's name be on any buildings that I design".[7] Much of this doubt came from Gehry's reputation for relying on the use of cheap materials in his architecture that were used in unconventional ways. With the Walt Disney Concert Hall being a project that demanded a high budget and an elegant style, Gehry did not seem like the right candidate for the job. However, Gehry's determination landed him the job of designing the hall, as he produced a design that caught the eye of Walt Disney's widow, Lilian.[7] His design included some of the elements of the deconstructivist architecture that he was known for, while still producing an elegant structure.

Construction

The project was initiated in 1987, when Lillian Disney, widow of Walt Disney, donated $50 million. Frank Gehry delivered completed designs in 1991. Construction of the underground parking garage began in 1992 and was completed in 1996. The garage cost had been $110 million, and was paid for by Los Angeles County, which sold bonds to provide the garage under the site of the planned hall.[8] Construction of the concert hall itself stalled from 1994 to 1996 due to lack of fundraising. Additional funds were required since the construction cost of the final project far exceeded the original budget. Plans were revised, and in a cost-saving move the originally designed stone exterior was replaced with a less costly stainless steel skin.[9]: 114 The needed fundraising restarted in earnest in 1996, headed by Eli Broad and then-mayor Richard Riordan. Groundbreaking for the hall was held in December 1999. Delay in the project completion caused many financial problems for the county of LA. The County expected to repay the garage debts by revenue coming from the Disney Hall parking users.[8]

Due to the mathematical complexity of Gehry's innovative design, he relied on computer software to produce his design in a way that could be completed by contractors. The technology, called CATIA (computer-aided three-dimensional interactive application) is typically used in the design process for French fighter jets, but its mathematical ability aided Gehry in his process of designing the Walt Disney Concert Hall.[7] Perhaps it is the angle-based design of the concert hall that required the use of CATIA, which can be seen on the exterior of the building. For example, the box columns on the north side of the Walt Disney Concert Hall are tilted forward at seventeen degrees.[10] The angular design was used by Gehry to "symbolize musical movement and the motion of Los Angeles".[10]

Upon completion in 2003, the project cost an estimated $274 million; the parking garage alone cost $110 million.[8] The remainder of the total cost was paid by private donations, of which the Disney family's contribution was estimated at $84.5 million with another $25 million from The Walt Disney Company. By comparison, the three existing halls of the Music Center cost $35 million in the 1960s (about $330 million in 2021 dollars).

Acoustics

As construction finished in the spring of 2003, the Philharmonic postponed its grand opening until the fall and used the summer to let the orchestra and Master Chorale adjust to the new hall. Performers and critics agreed that it was well worth this extra time taken by the time the hall opened to the public.[11] During the summer rehearsals a few hundred VIPs were invited to sit in including donors, board members and journalists. Writing about these rehearsals, Los Angeles Times music critic Mark Swed wrote the following account:

When the orchestra finally got its next [practice] in Disney, it was to rehearse Ravel's lusciously orchestrated ballet, Daphnis and Chloé. ... This time, the hall miraculously came to life. Earlier, the orchestra's sound, wonderful as it was, had felt confined to the stage. Now a new sonic dimension had been added, and every square inch of air in Disney vibrated merrily. Toyota says that he had never experienced such an acoustical difference between a first and second rehearsal in any of the halls he designed in his native Japan. Salonen could hardly believe his ears. To his amazement, he discovered that there were wrong notes in the printed parts of the Ravel that sit on the players' stands. The orchestra has owned these scores for decades, but in the Chandler no conductor had ever heard the inner details well enough to notice the errors.[11]

The hall met with laudatory approval from nearly all of its listeners, including its performers. In an interview with PBS, Esa-Pekka Salonen, former music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, said, "The sound, of course, was my greatest concern, but now I am totally happy, and so is the orchestra,"[12] and later said, "Everyone can now hear what the L.A. Phil is supposed to sound like."[13] This remains one of the most successful grand openings of a concert hall in American history.[citation needed]

As he was designing the Walt Disney Concert Hall, Gehry committed to producing a building that would promote the best acoustics possible. In order to do this, Gehry used ratios to test the acoustics of a model of the building, which was a 1:10 replica. Gehry had to scale all elements of the design accordingly, including the sound that he pumped into the model. Gehry reduced the wavelength of the sounds by a factor of ten in order to discover how his design would respond to the orchestras that would later perform in it to provide the best possible acoustics.[10]

The walls and ceiling of the hall are finished with Douglas-fir while the floor is finished with oak. Columbia Showcase & Cabinet Co. Inc., based in Sun Valley, CA, produced all of the ceiling panels, wall panels and architectural woodwork for the main auditorium and lobbies.[14] The Hall's reverberation time is approximately 2.2 seconds unoccupied and 2.0 seconds occupied.[15]

Regional Connector tunnel

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority had an agreement with the Los Angeles Music Center to use the most advanced noise-suppression measures for construction of the Regional Connector subway under 2nd Street where it passes the hall and the Colburn School of Music. Metro used procedures to ensure that the rumble of trains did not intrude on the sound quality of recordings made in the venues or mar audiences' musical experience within this sensitive stretch of the tunnel. Metro also built an elevated walkway from the Grand Avenue Arts/Bunker Hill station to the concert hall.[16]

Reflection problems

Originally, Frank Gehry had designed the Disney Concert Hall with a facade of stone, because "at night stone would glow," he told interviewer Barbara Isenberg. "Disney Hall would look beautiful at night in stone. It would have just been great. It would have been friendly. Metal at night goes dark. I begged them. No, after they saw Bilbao, they had to have metal."[17]

After the construction, modifications were made to the Founders Room exterior; while most of the building's exterior was designed with stainless steel given a matte finish, the Founders Room and Children's Amphitheater were designed with highly polished mirror-like panels. The reflective qualities of the surface were amplified by the concave sections of the Founders Room walls. Some residents of the neighboring condominiums suffered glare caused by sunlight that was reflected off these surfaces and concentrated in a manner similar to a parabolic mirror. The resulting heat made some rooms of nearby condominiums unbearably warm, caused the air-conditioning costs of these residents to skyrocket and created hot spots on adjacent sidewalks of as much as 140 °F (60 °C).[18] There was also the increased risk of traffic accidents due to blinding sunlight reflected from the polished surfaces. After complaints from neighboring buildings and residents, the owners asked Gehry Partners to come up with a solution. Their response was a computer analysis of the building's surfaces identifying the offending panels. In 2005, these were dulled by lightly sanding the panels to eliminate unwanted glare.[19]

Concert organ

The design of the hall included a large concert organ, completed in 2004, which was used in a special concert for the July 2004 National Convention of the American Guild of Organists. The organ had its public debut in a non-subscription[clarification needed] recital performed by Frederick Swann on September 30, 2004, and its first public performance with the Philharmonic two days later in a concert featuring Todd Wilson.[20]

The organ's façade was designed by architect Frank Gehry in consultation with organ consultant and tonal designer Manuel Rosales. Gehry wanted a distinctive, unique design for the organ. He would submit design concepts to Rosales, who would then provide feedback. Many of Gehry's early designs were fanciful, but impractical: Rosales said in an interview with Timothy Mangan of the Orange County Register, "His [Gehry's] earliest input would have created very bizarre musical results in the organ. Just as a taste, some of them would have had the console at the top and pipes upside down. There was another in which the pipes were in layers of arrays like fans. The pipes would have had to be made out of materials that wouldn't work for pipes. We had our moments where we realized we were not going anywhere. As the design became more practical for me, it also became more boring for him." Then, Gehry came up with the curved wooden pipe concept, "like a logjam kind of thing," says Rosales, "turned sideways." This design turned out to be musically viable.[21]

The organ was built by the German organ builder Caspar Glatter-Götz under the tonal direction and voicing of Manuel Rosales. It has an attached console built into the base of the instrument from which the pipes of the Positive, Great, and Swell manuals (keyboards) are playable by direct mechanical, or "tracker" key action, with the rest playing by electric key action;[22] this console somewhat resembles North-German Baroque organs, and has a closed-circuit television monitor set into the music desk. It is also equipped with a detached, movable console, which can be moved about as easily as a grand piano, and plugged in at any of four positions on the stage, this console has terraced, curved "amphitheatre"-style stop-jambs resembling those of French Romantic organs, and is built with a low profile, with the music desk entirely above the top of the console, for the sake of clear sight lines to the conductor. From the detached console, all ranks play by electric key and stop action.[23]

In all, there are 72 stops, 109 ranks, and 6,125 pipes; pipes range in size from a few inches/centimeters to the longest being 32 feet (9.75m) (which has a frequency of 16 hertz).[23]

The organ is a gift to the County of Los Angeles from Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. (the U.S. sales, marketing, service, and distribution arm of Toyota Motor Corporation).[24][25]

In popular culture

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

- The Hall was spoofed in The Simpsons episode "The Seven-Beer Snitch"; Gehry voiced himself in the episode where the town of Springfield had him design a new Concert Hall for the town.[27] The Concert Hall was then transformed into a jail by Mr. Burns. The character Snake eventually escapes from the prison while saying, "No Frank Gehry-designed prison can hold me!"

- The first ever movie premiere at the concert hall was in 2003, when The Matrix Revolutions held its world premiere.[28]

- The Walt Disney Concert Hall was briefly featured in the opening of the 2004 crime thriller Collateral. It is seen where the film's main protagonist, Max Durocher (Jamie Foxx), is carrying a bickering couple (Debi Mazar and Bodhi Elfman) in his cab.

- The Hall is featured in the video game Midnight Club: Los Angeles.

- In the opening moments of "Day 6" of 24, a suicide bomber destroyed a bus in the vicinity of the Concert Hall.

- It was featured in the 2007 film, Alvin and the Chipmunks.

- The 2007 film Fracture has a scene at the concert hall.[29]

- The Concert Hall held Ellen DeGeneres co-hosting for American Idol during the special week of Idol Gives Back. Rascal Flatts, Kelly Clarkson, and Il Divo performed here.

- This building was also used in the Iron Man (2008 release) movie briefly for a party for Stark Industries.[30]

- The finale of the 2008 movie Get Smart was filmed at the Concert Hall.[31]

- In the promotion picture for the television series Shark, the cast is standing in front of the Concert Hall.

- In the original pilot of the American TV remake of Life on Mars, the Hall features prominently in the sequence where Sam travels back to 1972. It is an emblem of the ultra-modern landscape that Sam is about to leave behind.

- On Everyday Italian, Giada De Laurentiis was preparing foods for her family and friends before she went there.

- "One Hour", a 3rd-season episode of NUMB3RS, extensively features the concert hall. The action begins outside the hall, and after a long series of events around town, the FBI winds up going inside the hall in order to rescue a young boy from his captors.

- Both the interior and the exterior of the building were filmed in extensively during the production of the 2009 film, The Soloist.[32]

- Filming was done on location at the Concert Hall for a fictional Boomkat music video in the CW's Melrose Place.

- The ABC show Brothers and Sisters often shows an exterior shot of Senator Robert McCallister's office that includes the Concert Hall. Also, Kitty proposed to Robert at a fundraiser held at the Hall

- It was featured in the History Channel show Life After People, where its stainless steel protects it from a raging wildfire.

- The exterior is featured prominently in the 2012 film Celeste and Jesse Forever.

- In the fifth episode of the French reality show Amazing Race, the show's contestants had to identify the Disney song a saxophonist was playing outside the concert hall.[33]

- It was also the place of shooting for various scenes from Glee's latest seasons as part of the fictional academy NYADA (New York Academy of Dramatic Arts).

- The Concert Hall's 2014–15 Opening Night Concert, a tribute to American composer John Williams, was recorded on September 24, 2014, for the television special A John Williams Celebration Gala.

- It was featured in the 2015 film Furious 7 during a chase.

- On the children's series SpongeBob SquarePants, the Philharmonic Concert Hall featured in the season 10 episode "Snooze You Lose" is modeled closely after the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

- The sixth episode of Top Chef: All-Stars L.A. featured the Concert Hall with contestants tasked with preparing dishes for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.[34]

- The seventh episode of the sixth and final season of Lucifer that aired in 2021 featured the Hall as the venue of the show's iconic wedding and after party scene.

- The Hall appeared in the Mickey Mouse episode, "Outback at Ya!" in the place of Sydney Opera House.

- In the 2021 film Annette, star soprano Ann Defrasnoux (Marion Cotillard) performs in a fictional opera at the Concert Hall. Sparks, the writer-composers of Annette, played two sold-out shows in the Hall in February 2022 including songs from the film.[35]

- In the second season of Star Trek: Picard, it was used as the stand-in for the Confederacy of Earth's Presidential Palace.

Restaurant

The concert hall houses Ray Garica's Astrid with collaborations with levy restaurants which offer other dining options throughout The Music Center complex.

Gallery

-

As seen from city hall in 2006

-

Panoramic view of Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles

-

Walt Disney Concert Hall at sunset June 2013

-

View from opposite corner of Grand Ave and 2nd Street

-

Profile view from Grand Avenue; the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion is to the right in the rear

-

Detail near entrance

-

Detail from the inner atrium

-

Viewed at night

-

Viewed looking north

-

Partial view

-

Main entrance at night

-

The exterior in winter 2007

-

Viewed from satellite

-

Detail atop main entrance

-

During construction in May 2001

-

During construction in May 2001

See also

- List of concert halls

- List of works by Frank Gehry

- The organization of the artist

- Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

- Joel Wachs, Los Angeles City Council member honored with Joel Wachs Square near the concert hall

References

- ^ https://www.cosentini.com/images/Project-Sheets/West-Experience.pdf

- ^ Kamin, Blair (October 26, 2003). "The wonderful world of Disney". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014.

- ^ Cavanaugh, William J.; Tocci, Gregory C.; Wilkes, Joseph A. (January 1, 2010). Architectural Acoustics: Principles and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470190524.

- ^ "Process | Walt Disney Concert Hall 10th Anniversary". wdch10.laphil.com. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Painter, Karen; Crow, Thomas E. (January 1, 2006). Late Thoughts: Reflections on Artists and Composers at Work. Getty Publications. ISBN 9780892368136.

- ^ Swed, Mark (October 19, 2003). "Sculpting the sound". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "10 Buildings That Changed America". 2022.

- ^ a b c Manville, Michael; Shoup, Donald (October 26, 2014). "People, Parking, and Cities" (PDF). UC Transportation Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2014.

- ^ Gehry, Frank (2002). gehry talks. Universe Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7893-0682-1.

- ^ a b c "AD Classics: Walt Disney Concert Hall / Gehry Partners". October 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Mark Swed (October 29, 2003). "Now comes the true test". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Philharmonic Inaugurates Walt Disney Concert Hall". PBS. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Valerie Scher (October 25, 2003). "Disney Hall opens with a bang". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ "Columbia Showcase & Cabinet Co. Inc. – An Acoustical Journey –". Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Building Details and Acoustics Data" (PDF). Nagata Acoustics. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ Boehm, Mike (July 2, 2014). "Metro commits to deal ensuring subway won't hurt Disney Hall acoustics". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014.

- ^ Craven, Jackie Craven Jackie; Writing, Doctor of Arts in. "Skins of Metal - A Hazard in Architecture". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ Schiler, Marc; Valmont, Elizabeth. "Microclimactic Impact: Glare around the Walt Disney Concert Hall" (PDF). Society of Building Science Educators. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2006. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Coates, Chris (March 21, 2005). "Dimming Disney Hall; Gehry's Glare Gets Buffed". Los Angeles Downtown News. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Steven (September 19, 2004). "The best of the season". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Timothy Mangan (September 30, 2004). "Pipe dreams at Disney Hall; The concert venue's fantastical organ is finally ready for unveiling". Orange County Register (California).

- ^ Rodriquez, Paul D. "Inside the Disney Hall Organ" (PDF). Los Angeles Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2019 – via Rosales Organ Builders.

- ^ a b "Rosales Organ Builders, Opus 24 (Walt Disney Concert Hall)". Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- ^ Wachtell, Esther (August 1991). "Using all the fund-raising tools: by giving its volunteers all the resources they needed to do the job, The Music Center of Los Angeles increased its campaign goal 15 percent to $ 17.6 million, despite the recession". Fund Raising Management. 22 (6): 23. ISSN 0016-268X.

- ^ PAUL KARON (November 24, 1997). "Toyota ups hall donation". Daily Variety.

- ^ "#10 Walt Disney Concert Hall". 10 Buildings that Changed America. WTTW. 2013. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013. Webpage features include a photo slideshow, video from the televised program (4:47), and "web exclusive video" (3:35).

- ^ simp15.jpg Archived June 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Downey, Ryan J. (October 28, 2003). "Keanu Reeves Says Goodbye To Neo At Premiere of 'The Matrix Revolutions'". MTV. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (April 11, 2017). "Fracture review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "Iron Man | 2008". movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Ferguson, Dana (September 20, 2013). "Filming at Disney Hall: Always ready for its close-up". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "The Soloist 2009 - Walt Disney Concert Hall". Casting Architecture. August 31, 2012. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "Amazing Race : Ouceni et Lassana éliminés, Marilyn Monroe ressuscitée ?" [Amazing Race: Ouceni and Lassana eliminated, Marilyn Monroe resurrected?]. Purepeople (in French). November 20, 2012. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Struble, Cristine (April 23, 2020). "Top Chef All Stars LA Season 17 episode 6 preview: A flavor symphony". FanSided. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Sparks Asks 'So May We Start?' in a Disney Hall Gig That Shows How Far the Maels Are from Finished: Concert Review". February 9, 2022.

Further reading

- Symphony: Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall. NEW YORK: Harry O. Abrams, 2006. ISBN 0-8109-4981-4, ISBN 0-8109-9122-5.

External links

- Official website at Los Angeles Music Center Archived March 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Walt Disney Concert Hall – web page of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

- Archive of stories from the Los Angeles Times

- Article and images at arcspace.com

- Images in B&W of the Disney Concert Hall

- Photographs of exterior and interior of the Disney Concert Hall Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Photograph: Exterior detail of the Disney Concert Hall

- Photographs of Disney Concert Hall exterior and architectural details

- Controlling Chaos

- Recent Photos of Disney Concert Hall

- Photos of Disney Concert Hall

- Virtual Tour of Walt Disney Concert Hall

- Walt Disney Concert Hall Calendar

- Theatre Consultant Theatre Projects website