FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

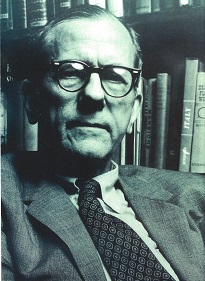

William Andrew Swanberg (November 23, 1907 in St. Paul, Minnesota – September 17, 1992 in Southbury, Connecticut)[1] was an American biographer. He is known for Citizen Hearst, a biography of William Randolph Hearst, which was recommended by the Pulitzer Prize board in 1962 but overturned by the trustees.[2] He won the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography for his 1972 biography of Henry Luce,[3] and the National Book Award in 1977 for his 1976 biography of Norman Thomas.[4]

Background

Swanberg was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota in 1907, and earned his B.A. at the University of Minnesota in 1930.[5]

With grudging and only partial help from his father, who wanted his son to be a cabinet maker like himself, Swanberg earned his degree.

Career

Upon graduation, he found employment as a journalist with such local daily newspapers as the St. Paul Daily News and the Minneapolis Star unsatisfactory, as their staff were shrinking during the Great Depression. Swanberg instead held a succession of low-paying manual labor jobs. After five years he followed a college friend to New York City in September 1935. After months of anxious job-hunting he secured an interview at the Dell Publishing Company with president George T. Delacorte Jr., and was hired as an assistant editor of three lowbrow magazines. Money saved in the next months enabled him to return briefly to the Midwest to marry his college sweetheart Dorothy Green, and bring her to New York. He soon began to climb the editorial ladder at Dell, and by 1939 he was doing well enough to buy a house in Connecticut.

When the United States entered World War II, Swanberg was 34 years old, father of two children, and suffering from a hearing disability. Rejected by the U.S. Army, in 1943 he enlisted in the Office of War Information and, after training, was sent to England following D-Day. In London, amid the V-1 and V-2 attacks, he prepared and edited pamphlets to be air-dropped behind enemy lines in France and later in Norway.[6] With the end of the war he returned in October 1945 to Dell and the publishing world.

Swanberg did not return to magazine editing but instead did freelance work within and without Dell. By 1953, he began carving out time for researching his first book (Sickles), which Scribner's purchased, beginning a long-term association. Swanberg's early hopes of newspaper work never materialized, but by the mid-1950s he had established himself as scholarly biographer. His efforts proved to be labor-intensive and required up to four years apiece, even when assisted by the research and transcription efforts of his wife Dorothy. Upon turning 80 in 1987, Swanberg attempted one last biography, about William Eugene “Pussyfoot” Johnson (1862–1945).[7] He was at work on that project when he succumbed to heart failure at his typewriter in Southbury, Connecticut on September 17, 1992.

Rejection for Pulitzer Prize

Swanberg's 1961 book Citizen Hearst: A Biography of William Randolph Hearst was recommended for a Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography by the advisory board but rejected by the trustees of Columbia University, apparently because they thought that Hearst was not dignified enough to be the subject of the award. It was the first time in 46 years that the trustees rejected a recommendation from the advisory board, and the news caused sales to soar.[1]

Awards

- 1959: Christopher Award and Minnesota Centennial Award for First Blood

- 1960: Guggenheim fellow

- 1961: Frank Luther Mott-Kappa Tau Alpha Award for Citizen Hearst

- 1962: Pulitzer Prize for Citizen Hearst (overturned by trustees of Columbia University, who administer the prize, because subject (William Randolph Hearst) failed to meet "eminent example of the biographer's art as specified in the prize definition"[2]

- Van Wyck Brooks Award for nonfiction (1967)

- 1973: Pulitzer Prize for Luce and His Empire[3]

- 1977: National Book Award in Biography for Norman Thomas: The Last Idealist[4]

Legacy

Swanberg's papers are archived at Columbia University.

Works

In a statistical overview derived from writings by and about William Andrew Swanberg, OCLC/WorldCat [clarification needed] encompasses roughly 30+ works in 100+ publications in 5 languages and 16,000+ library holdings.[8]

- Sickles the Incredible, 1956. Civil War General Daniel Edgar Sickles.

- First Blood: The Story of Ft. Sumter, 1957[9]

- Jim Fisk: The Career of an Improbable Rascal, 1959. "Diamond" Jim Fisk.

- Citizen Hearst: A Biography of William Randolph Hearst, 1961

- Dreiser, 1965

- Pulitzer, 1967

- The Rector and the Rogue, 1969

- Luce and His Empire, 1972

- Norman Thomas: The Last Idealist, 1976

- Whitney Father, Whitney Heiress, 1980

References

- ^ a b www.nytimes.com

- ^ a b Hohenberg, John. The Pulitzer Diaries: Inside America's Greatest Prize. 1997. p. 109.

- ^ a b "Biography or Autobiography". Past winners and finalists by category. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2012-03-17.

- ^ a b "National Book Awards – 1977". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-17.

- ^ Nakamura, Joyce, ed. (1991). "W. A. Swanberg 1907-". Contemporary Authors. Autobiography. Vol. 13. Detroit and London: Gale Research Inc. pp. 260–61. ISBN 0810345129. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ Nakamura 1991, p. 264

- ^ Nakamura 1991, p. 277

- ^ WorldCat Identities: Swanberg, W. A. 1907-

- ^ Hill Jr., L. Gordon (October 1958). "Review of First Blood: The Story of Ft. Sumter by W. A. Swanberg". Military Review. 38 (7): 112.

External links

- W. A. Swanberg Papers Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania