FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

Victor Berger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Wisconsin's 5th district | |

| In office March 4, 1923 – March 3, 1929 | |

| Preceded by | William H. Stafford |

| Succeeded by | William H. Stafford |

| In office March 4, 1919 – November 10, 1919 Unseated | |

| Preceded by | William H. Stafford |

| Succeeded by | William H. Stafford (1921) |

| In office March 4, 1911 – March 3, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | William H. Stafford |

| Succeeded by | William H. Stafford |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Victor Luitpold Berger February 28, 1860 Nieder-Rehbach, Austria (now Romania) |

| Died | August 7, 1929 (aged 69) Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Political party | Socialist |

Victor Luitpold Berger (February 28, 1860 – August 7, 1929) was an Austrian–American socialist politician and journalist who was a founding member of the Social Democratic Party of America and its successor, the Socialist Party of America. Born in the Austrian Empire (present-day Romania), Berger immigrated to the United States as a young man and became an important and influential socialist journalist in Wisconsin. He helped establish the so-called Sewer Socialist movement, but also sparked the American Socialist Party's nativist turn. In 1910, he was elected as the first Socialist to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing a district in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

In 1919, Berger was convicted of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 for publicizing his anti-interventionist views and as a result was denied the seat to which he had been twice elected in the House of Representatives.[1] The verdict was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court in 1921 in Berger v. United States, and Berger was elected to three successive terms in the 1920s.[2]

Early years

Berger was born into a Jewish family[3][4] on February 28, 1860, in Niederrehbach, Austrian Empire (modern Romania).[5][6] He was the son of Julia and Ignatz Berger.[7] He attended the Gymnasium at Leutschau (today in Slovakia), and the major universities of Budapest and Vienna.[8] In 1878, he immigrated to the United States with his parents,[6][9] settling near Bridgeport, Connecticut.[10]

Berger's wife, Meta, later claimed that Berger had left Austria-Hungary to avoid conscription into the military.[11]

In 1881, Berger settled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, home to a large population of German Americans and a very active labor movement. Berger joined the Socialist Labor Party (then headed by Daniel de Leon). In 1892, Berger became the editor of Milwaukee Arbeiter-Zeitung, and changed its name to Vorwärts ![12][13] He also served as editor of another paper: Die Wahrheit [The Truth]. Berger taught German in the public school system. His future father-in-law was the school commissioner.

In 1897, he married a former student, Meta Schlichting, an active socialist organizer in Milwaukee. For many years, she was a member of the University of Wisconsin Board of Regents.[14] The couple raised two daughters, Doris (who later went on to write television shows such as General Hospital, with her husband Frank) and Elsa, speaking only German in the home. The parents were strongly oriented to European culture.[15]

Socialist organizing

Berger was credited by trade union leader Eugene V. Debs for having won him over to the cause of socialism. Jailed for six months for violating a federal anti-strike injunction in the 1894 strike of the American Railway Union, Debs turned to reading:

Books and pamphlets and letters from socialists came by every mail and I began to read and think and dissect the anatomy of the system in which workingmen, however organized, could be shattered and battered and splintered on a single stroke [...] It was at this time, when the first glimmerings of socialism were beginning to penetrate, that Victor L. Berger — and I have loved him ever since — came to Woodstock [prison], as if a providential instrument, and delivered the first impassioned message of socialism I had ever heard — the very first to set the wires humming in my system. As a souvenir of that visit there is in my library a volume of Capital by Karl Marx, inscribed with the compliments of Victor L. Berger, which I cherish as a token of priceless value.[16]

In 1896, Berger was a delegate to the People's Party Convention in St. Louis.[17]

Berger was short and stocky, with a studious demeanor, and had both a self-deprecating sense of humor and a volatile temper. Although loyal to friends, he was strongly opinionated and intolerant of dissenting views.[18] His ideological sparring partner and comrade Morris Hillquit later recalled of Berger that

He was sublimely egotistical, but somehow his egotism did not smack of conceit and was not offensive. It was the expression of deep and naive faith in himself, and this unshakable faith was one of the mainsprings of his power over men.[19]

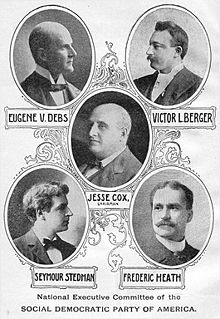

Berger was a founding member of the Social Democracy of America in 1897 and led the split of the "political action" faction of that organization to form the Social Democratic Party of America (SDP) in 1898. He was a member of the governing National Executive Committee of the SDP for its entire duration.

Berger was a founder of the Socialist Party of America in 1901 and played a critical role in the negotiations with an east coast dissident faction of the Socialist Labor Party in the establishment of this new political party. Berger was regarded as one of the party's leading revisionist Marxists, an advocate of the trade union-oriented and incremental politics of Eduard Bernstein. He advocated the use of electoral politics to implement reforms and thus gradually build a collectivist society.[20]

Relative to other contemporary socialist politicians, Berger was a racial conservative. He regularly fought Eugene V. Debs on the subject.[21][22] Berger was terrified of Asian immigrants, who he believed would out-reproduce white Americans and further complicate the socialist movement's cross-racial solidarity. Between 1907 and 1912, he masterminded racially-discriminatory immigration restrictions in the Socialist Party platform.[23] His views on Jim Crow were only slightly more nuanced: while Berger wrote in a 1902 editorial that "There can be no doubt that the negroes and mulattoes constitute a lower race — that the Caucasian and even the Mongolian have the start on them in civilization by many years," he does not appear to have believed that this justified "the barbarous behavior of American whites towards the negroes".[24] Instead, Berger argued that segregation was a symptom of an elite capture that left the American legal system indifferent to the poor of every race.[24]

Berger was a man of the written word and back room negotiation, not a notable public speaker. He retained a heavy German accent and had a voice which did not project well. As a rule he did not accept outdoor speaking engagements and was a poor campaigner, preferring one-on-one relationships to mass oratory.[25] Berger was, however, a newspaper editorialist par excellence. Throughout his life he published and edited a number of different papers, including the German language Vorwärts! ("Forward") (1892-1911), the Social-Democratic Herald (1901-1913), and the Milwaukee Leader (1911-1929).[2]

First term in Congress

Berger ran for Congress and lost in 1904 before winning Wisconsin's 5th congressional district seat in 1910 as the first Socialist to serve in the United States Congress. In Congress, he focused on issues related to the District of Columbia and also more radical proposals, including eliminating the President's veto, abolishing the Senate,[26] and the social takeover of major industries. Berger gained national publicity for his old-age pension bill, the first of its kind introduced into Congress. Less than two weeks after the Titanic passenger ship disaster, Berger introduced a bill in Congress providing for the nationalization of the radio-wireless systems. A practical socialist, Berger argued that the wireless chaos which was one of the features of the Titanic disaster had demonstrated the need for a government-owned wireless system.[27]

Although he did not win re-election in 1912, 1914 or 1916, he remained active in Wisconsin and Socialist Party politics. Berger was especially involved in the biggest party controversy of the pre-war years, the fight between the SP's centrist "regular" bloc against the syndicalist left wing over the issue of "sabotage". The bitter battle erupted in full force at the 1912 National Convention of the Socialist Party, to which Berger was again a delegate. At issue was language to be inserted into the party constitution which called for the expulsion of "any member of the party who opposes political action or advocates crime, sabotage, or other methods of violence as a weapon of the working class to aid in its emancipation."[28] The debate was vitriolic, with Berger, somewhat unsurprisingly, stating the matter in its most bellicose form:[29]

Comrades, the trouble with our party is that we have men in our councils who claim to be in favor of political action when they are not. We have a number of men who use our political organization — our Socialist Party — as a cloak for what they call direct action, for IWW-ism, sabotage and syndicalism. It is anarchism by a new name. ...

Comrades, I have gone through a number of splits in this party. It was not always a fight against anarchism in the past. In the past we often had to fight utopianism and fanaticism. Now it is anarchism again that is eating away at the vitals of our party.

If there is to be a parting of the ways, if there is to be a split — and it seems that you will have it, and must have it — then, I am ready to split right here. I am ready to go back to Milwaukee and appeal to the Socialists all over the country to cut this cancer out of our organization.

The regulars won the day handily at the Indianapolis convention of 1912, with a successful recall of IWW leader "Big Bill" Haywood from the SP's National Executive Committee and an exodus of disaffected left wingers following shortly thereafter. The remaining radicals in the party remembered bitterly Berger's role in this affair and the ill feelings continued to fester until erupting anew at the end of the decade.

World War I

Although Berger's views on World War I were complicated by the Socialist view and the difficulties surrounding his German heritage, he supported his party's stance against the war. When the United States entered the war and passed the Espionage Act of 1917, Berger's continued opposition made him a target. He and four other Socialists were indicted under the Espionage Act in February 1918. The trial followed on December 9 of that year, and on February 20, 1919, Berger was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in federal prison.

During the 1918 Wisconsin special Senate election, Berger ran for the seat despite being under federal indictment. His newspaper, the Milwaukee Leader, had printed a number of anti-war articles, leading the postal service to revoke the paper's second-class mail privileges. Despite these circumstances, Berger won 26% of the vote statewide in an April special election to fill a Senate vacancy, including winning 11 counties, in a three-way race.[30]

The espionage trial was presided over by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.[31] Berger's conviction was appealed and was ultimately overturned by the US Supreme Court on January 31, 1921, which found that Landis had improperly presided over the case after the filing of an affidavit of prejudice.[32]

Even though Berger was under indictment, the voters of Milwaukee once again elected him to the House of Representatives in 1918. When he arrived in Washington to claim his seat, Congress formed a special committee to determine whether a convicted felon and war opponent should be seated as a member of Congress. On November 10, 1919, they concluded that he should not, and they declared the seat vacant,[33] disqualifying him pursuant to Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[34]

Wisconsin promptly held a special election to fill the vacant seat. On December 19, 1919, they elected Berger a second time, and on January 10, 1920, the House again refused to seat him. The seat remained vacant until January 1921, after his previous electoral opponent, Republican William H. Stafford, once again prevailed over Berger in the 1920 general election.[35]

Second stint in Congress

Berger defeated Stafford in 1922 and was reelected in 1924 and 1926. In those terms, he dealt with Constitutional changes, a proposed old-age pension, unemployment insurance, and public housing. He also supported the diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union and the revision of the Treaty of Versailles. After his defeat by Stafford in 1928, he returned to Milwaukee and resumed his career as a newspaper editor.

Death

On July 16, 1929, while crossing the street outside his newspaper office, Berger was struck by a streetcar travelling on North Third Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Drive) at the intersection with West Clarke Street in Milwaukee. The accident fractured his skull, and he died of his injuries on August 7, 1929. Prior to burial at Forest Home Cemetery his body lay in state at City Hall. 75,000 residents of the city came to pay their respect.[36]

Legacy

According to historian Sally Miller:[37]

- Berger built the most successful socialist machine ever to dominate an American city....[He] concentrated on national politics...to become one of the most powerful voices in the reformist wing of the national Socialist party. His commitment to democratic values and the non-violent socialization of the American system led the party away from revolutionary Marxist dogma. He shaped the party into force which, while struggling against its own left wing, symbolize participation in the political order to attain social reforms.... In the party schism of 1919, Berger opposed allegiance to the emergent Soviet system. His shrunken party echoed his preference for peaceful, democratic, and gradual transformation to socialism.

Berger's papers are housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society, with smaller numbers of items dispersed to other locations.[17] The complete run of the Milwaukee Leader exists on microfilm published by the Wisconsin Historical Society and on site at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.[38]

Works

Victor Berger's writing was voluminous, but rarely reproduced in book or pamphlet form outside of the newspapers in which it first appeared. In 1912, the Social-Democratic Publishing Co published a collection of his works in a publication entitled Berger's Broadsides.[39] In 1929, the Milwaukee Leader published the Voice and Pen of Victor L. Berger: Congressional Speeches and Editorials (1860–1929) which also included an obituary.[40]: 108 This publication included Berger's phrase regarding draining the swamp in reference to his assertion that the economic crises such as the Panic of 1893, were "hastened' by excessive profits—the $900,000,000 to Standard Oil "magnates". According to Daniel Yergin in his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (1990), at the time the general public considered the Standard Oil conglomerate which was controlled by a small group of directors to be "all-pervasive" and "completely unaccountable".[41]: 96–98

[Y]et as long as capitalism lasts, speculation is absolutely necessary and unavoidable in order to protect the system from stagnation." So this is another evil that is inherent in this system. It cannot be avoided any more than malaria in a swampy country. And the speculators are the mosquitos. We should have to drain the swamp-change the capitalist system-if we want to get rid of those mosquitos. Teddy Roosevelt, by starting a little fire here and there to drive them out, is simply disturbing them. He is causing them to swarm, which makes it so much more intolerable for us poor, innocent inhabitants of this big capitalist swamp.

— Victor L. Berger. Berger's Broadsides (1860–1912)

See also

- Meyer London

- Espionage Act of 1917

- First Red Scare

- List of Jewish members of the United States Congress

- Palmer Raids

- Sewer Socialism

- Socialist Party of America

- Social-Democratic Party of Wisconsin

- Unseated members of the United States Congress

Footnotes

- ^ "The Espionage Act and the "Golden Key" to Stop the State". Center for a Stateless Society. Archived from the original on 2018-09-04. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ^ a b "Victor L. Berger | Encyclopedia of Milwaukee". emke.uwm.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ See: Rafael Medoff, Jewish Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 330.

- ^ Mark Avrum Ehrlich, Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture, Volume 1, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2009, p. 593.

- ^ "Viktor L. Berger gestorben" [Victor L. Berger dead]. Vorwärts (in German). Vol. 46, no. 367. Berlin. 8 August 1929. p. 2. urn:nbn:de:bo133-1-199. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

Der Vorkämpfer der Amerikanischen Sozialismus, Viktor L. Berger, ist heute gestorben. Er war am 28. Februar 1860 in Niederrehbach (Siebenbürgen, damals Ungarn) geboren....Unfäßlich des Internationalen Sozialistenkongresses in Hamburg 1923 besuchte Victor [sic] Berger mit seiner Frau auch die "Vorwärts"-Redaktion und seine Heimat, die inzwischen zu Rumänien geschlagen war.

[The vanguard of American socialism, Victor L. Berger, died today. He was born on 28 February 1860 in Niederrehbach (Transylvania, then-Hungary)....Astonishingly, at the International Socialist Congress of Hamburg, 1923, Victor Berger and his wife also visited the editorial staff of [this paper] and his homeland, which in the intervening time had been ceded to Romania.] Although the borders of interwar Romania do not coincide with modern Romania, it has retained Transylvania entirely. The modern name for Niederrehbach is unclear; it may not have been an urban settlement. - ^ a b Bekker, Jon (2008). "Berger, Victor". In Vaughn, Steven L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of American Journalism. CRC Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-203-94216-1.

- ^ Whitman, Alden (1985). American Reformers: An H.W. Wilson Biographical Dictionary. H.W. Wilson Company. ISBN 978-0-8242-0705-2.

- ^ Dodge, Andrew R. (2005). "Berger, Victor Luitpold". Biographical directory of the United States Congress, 1774–2005. Government Printing Office. p. 647. ISBN 978-0-16-073176-1.

- ^ Sally M. Miller, "Victor Louis Berger," Historical Dictionary of the Progressive Era, 1890–1920. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1988, p. 38.

- ^ Miller 1973, p. 17.

- ^ Thomas, William H. (2008). Unsafe for democracy: World War I and the U.S. Justice Department's covert campaign to suppress dissent. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-299-22890-3.

- ^ Quint 1964, p. 286.

- ^ Chronicling America. Browse Issues: Vorwärts! Archived 2024-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Constantine, J. Robert, ed. (1990). Letters of Eugene V. Debs, Volume 1. University of Illinois Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-252-01742-1.

- ^ Miller 1973, p. 22.

- ^ Debs, Eugene V. (April 1902). "How I Became a Socialist". The Comrade. 1 (7): 147–148. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27.

- ^ a b US Congress item B000407

- ^ Miller 1973, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Hillquit, Morris (1934). Loose Leaves from a Busy Life. New York: Macmillan. p. 53.

- ^ Miller 1973, p. 38, which notes that Berger "opposed orthodox Marxists, who, in turn, called [Berger] an opportunist". This refers to the revolutionary socialist left wing rather than the "orthodox Marxist" followers of Karl Kautsky, which was the majority tendency in the Socialist Party of this era.

- ^ Jones, William P. (Fall 2008). "Nothing Special to Offer the Negro". International Labor and Working-Class History (74). Cambridge University Press: 214. JSTOR 27673131, later adapted as Jones, William P. (August 11, 2015). "Something to Offer". Jacobin. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Kipnis 1952, p. 287.

- ^ Kipnis 1952, pp. 277–288.

- ^ a b Berger, Victor L. (31 May 1902). "The Misfortune of the Negroes" (PDF). Social Democratic Herald. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024. For a less charitable reading of the editorial, see Shannon, David A. (1967) [1955]. The Socialist Party of America. Chicago: Quadrangle Books. p. 50.

- ^ Miller 1973, pp. 23–24.

- ^ "House Member Introduces Resolution To Abolish the Senate". Archived from the original on 2018-01-13. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ^ ""FEDERAL OWNERSHIP URGED FOR WIRELESS; Berger, Socialist Representative, Introduces Bill Based on Titanic's Chaos of Messages." The New York Times, April 25, 1912". Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Amendment to Article 2, Section 6, proposed by William Lincoln Garver of Missouri. John Spargo (ed.), National Convention of the Socialist Party Held at Indianapolis, Ind., May 12 to 18, 1912: Stenographic Report. Chicago: The Socialist Party, [1912], p. 122. Hereafter: 1912 National Convention Stenographic Report.

- ^ Speech of Victor Berger 1912 National Convention Stenographic Report, p. 130.

- ^ ""Victor Berger Campaign Banner," United States Senate campaign banner for Milwaukee Socialist Congressman Victor L. Berger, April 1918 (Museum object #1992.168) and Historical Essay, from the Wisconsin Historical Society". Archived from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ Transcript of the trial

- ^ Berger et al. v. United States, 255 U.S. 22, 41 S.Ct. 230 (1921).

- ^ "Chapter 157: The Oath As Related To Qualifications", Cannon's Precedents of the U.S. House of Representatives, vol. 6, January 1, 1936, archived from the original on February 16, 2011, retrieved April 9, 2013

- ^ "In regard to the first question, your committee concurs with the opinion of the special committee appointed under House resolution No. 6, that Victor L. Berger, the contestee, because of his disloyalty, is not entitled to the seat to which he was elected, but that in accordance with the unbroken precedents of the House, he should be excluded from membership; and further, that having previously taken an oath as a Member of Congress to support the Constitution of the United States, and having subsequently given aid and comfort to the enemies of the United States during the World War, he is absolutely ineligible to membership in the House of Representatives under section 3 of the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States."

- ^ United States Congress. "William Henry Stafford (id: S000777)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ Beck 1982, Vol. I, p. 133.

- ^ Sally Miller, "Berger, Victor Louis," in John A. Garraty, ed., Encyclopedia of American Biography (1974) pp 87–88.

- ^ The Milwaukee Leader, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries, MadCat.

- ^ Victor L. Berger (1912), Berger's Broadsides (1860–1912), Milwaukee: Social-Democratic Publishing Co, retrieved February 21, 2017

- ^ Victor L. Berger, Voice and Pen of Victor L. Berger: Congressional Speeches and Editorials (1860–1929), Milwaukee Leader via Princeton University, archived from the original on November 17, 2018, retrieved February 21, 2017

- ^ Daniel Yergin (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 910. ISBN 978-0-671-50248-5.

Further reading

- Beck, Elmer A. The Sewer Socialists: A History of the Socialist Party of Wisconsin, 1897–1940. (2 vols.) Fennimore, WI: Westburg, 1982.

- Benoit, Edward A. "A Democracy of Its Own: Milwaukee's Socialisms, Difference and Pragmatism". Thesis. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2009.

- Brookhiser, Richard. "Thunder on the Left: Victor Berger". HistoryNet, February 8, 2019.

- Kates, James. "Editor, publisher, citizen, socialist: Victor L. Berger and his Milwaukee Leader." Journalism History 44.2 (2018): 79–88.

- Kipnis, Ira. The American Socialist Movement, 1897–1912. New York: Columbia University Press, 1952.

- Miller, Sally M. "Victor L. Berger and the Promise of Constructive Socialism, 1910–1920" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1966. NK00653); later republished Greenwood Press (1973).

- Muzik, Edward J. "Victor L. Berger: A Biography". (Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 1960; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1960. 6004782).

- Muzik, Edward J. "Victor L. Berger: Congress and the Red Scare". Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 47, no. 4 (Summer 1964).

- Nash, Roderick. "Victor L. Berger: Making Marx Respectable". Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 47, no. 4 (Summer 1964).

- Quint, Howard H. The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1953. 2nd edition Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1964.

- United States Congress. "Berger, Victor Luitpold (id: B000407)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Wachman, Marvin. History of the Social Democratic Party of Milwaukee, 1897–1910. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1945.

Primary sources

- Berger, Victor L. "A Leading American Socialist's View Of the Peace Problem." Current History 27.4 (1928): 471–477.

- Stedman, Seymour. "Victor L. Berger [and Others] Plaintiffs in Error, Vs. United States of America, Defendant in Error: Error to the District Court of the United States for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. Brief for Plaintiffs in Error" (1918).

- Stevens, Michael E. & Ellen D. Goldlust-Gingrich, (eds.). The Family Letters of Victor and Meta Berger, 1894–1929. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2009.

External links

- Victor Berger Archive at marxists.org

- Works by or about Victor L. Berger at the Internet Archive

- Representative Victor Berger of Wisconsin, the First Socialist Member of Congress U.S. House of Representatives Archives

- "Burgher Berger.", Time Magazine, Aug. 19, 1929.

- Dreier, Peter. "Why Has Milwaukee Forgotten Victor Berger?"

- Glende, Philip M. "Victor Berger's Dangerous Ideas"

- Harrison, Emily. "The Case of Victor L. Berger: Drawing the Line Between Dissent and Disloyalty"

- Spargo, John. "Hon. Victor L. Berger: The First Socialist Member of Congress," The American Magazine, 1911.

- House Member Introduces Resolution to Abolish the Senate

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Constitutional Minutes episode about Victor Berger at the American Archive of Public Broadcasting