FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

| Valentina of Milan | |

|---|---|

| Duchess of Orléans | |

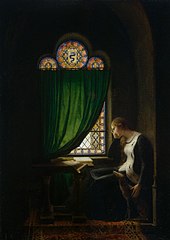

Valentina Visconti receiving Honoré Bonet's Apparicion maistre Jehan de Meun, c. 1398. Illumination on parchment, BnF | |

| Countess of Vertus | |

| Tenure | 17 August 1389 – 4 December 1408 |

| Predecessor | Gian Galeazzo Visconti |

| Successor | Philip of Orléans |

| Born | Valentina Visconti 1371 Pavia, Visconti fiefdoms, Italy |

| Died | 1408 (aged 37) Château de Blois, Orléanais, France |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Visconti |

| Father | Gian Galeazzo Visconti |

| Mother | Isabella of France |

Valentina Visconti (1371 – 4 December 1408) was a countess of Vertus, and duchess consort of Orléans as the wife of Louis I, Duke of Orléans, the younger brother of King Charles VI of France. As duchess of Orléans she was at court and acquired the enmity of the Queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, and was subsequently banned from the court and had to leave Paris. Due to political animosity, Valentina's husband was murdered in 1407. She died on 4 December 1408.

Life

Valentina was born in Pavia as the second of the four children of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the first Duke of Milan, and his first wife Isabelle,[1] a daughter of King John II the Good of France.[2] After her mother's death in childbirth in 1373, Valentina and her siblings were raised by their paternal grandmother Bianca of Savoy and aunt Violante Visconti.[3] The deaths of her brothers Carlo (1374), Gian Galeazzo (1376) and Azzone (1381) left Valentina as the only surviving child of her parents' marriage and the Countess of Vertus, a title she shared with her spouse.

Betrothals

In 1379, Valentina was betrothed to her cousin Carlo Visconti, Lord of Parma, son of Bernabò Visconti, and a papal dispensation was even granted;[4] however, Bernabò later annulled the betrothal and, in 1382, married his son to a French noblewoman, Beatrice of Armagnac.

In 1385 Gian Galeazzo became the sole ruler over the Visconti inheritance, and with this Valentina's status changed considerably.[5] At this point, the new Lord of Milan opened negotiations with King Wenceslaus of Germany and Bohemia for a marriage between Valentina and his half-brother John of Görlitz; at the same time, he also negotiated a union with Louis II of Anjou, titular King of Naples.[5] However, Marie of Blois, Dowager Duchess of Anjou finally cancelled the negotiations, and then Gian Galeazzo turned his attention to his nephew-by-marriage Louis, Duke of Touraine, second son of King Charles V of France and brother of the reigning Charles VI.[6][7] King Wenceslaus became aware of the double game of Gian Galeazzo, and broke off the negotiations with a letter full of insults, leaving Louis, her first cousin, the only suitor of Valentina.[5]

Marriage

Because of the close relationship between bride and groom, a papal dispensation was granted on 25 November 1386, and the marriage contract was signed on 27 January 1387 in Paris.[8] Valentina received as a dowry the County of Vertus (which was the dowry of her own mother at the time of her marriage in 1348) and the city of Asti, with the sums of 450,000 florins in cash and 75,000 florins in jewelry.[9] In the contract was also stipulated that in absence of male heirs, Valentina would inherit the Visconti dominions. It was because of this, that her grandson Louis XII of France claimed the Duchy of Milan and embarked on the Italian Wars. The marriage by proxy was celebrated three months later, on 8 April, in both the Milanese and French courts.

Valentina was only able to leave Milan for France on 23 June 1389, because of "reasons of security" given to her father: in fact, Gian Galeazzo wanted to amend the marriage contract after the pregnancy of his second wife Caterina Visconti (another Bernabò's daughter) ended. Only after the birth of his son Gian Maria on 7 September 1388 did he feel secure enough to send his daughter to France.

Escorted by her paternal cousin Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy and a retinue of 300 knights, Valentina was finally handed to Louis's envoys. The formal marriage took place in the city of Melun, on 17 August 1389.

In June 1392 her husband exchanged the Duchy of Touraine for the Duchy of Orléans;[10] since then, Valentina was styled Duchess of Orléans. Because of intrigues at the court of Charles VI of France and the enmity of the queen, Isabeau of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, Valentina was exiled from the court and had to leave Paris. There were rumours that Isabeau was having an affair with Louis and that Valentina was very close to the King, who was in poor mental health.

A patroness of Eustache Deschamps, who wrote poetry in her honour, Valentina was also the mother of one of France's most famous poets, Charles of Orléans.

Valentina's husband's murder was orchestrated by his cousin and political rival John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy in 1407.[11] Valentina outlived her husband by only a little over a year, dying at Blois on 4 December 1408.[12]

Burial

Valentina was buried at the Celestins convent of the Orleans chapel in Paris.[13] Her monument tomb was commissioned in 1508 by her grandson Louis XII of France.[13] It was moved to Basilica of Saint-Denis between 1817 and 1818.[13]

Issue

Valentina and Louis had:

- Charles, Duke of Orléans (Hôtel royal de Saint-Pol, Paris, 24 November 1394 - Château d'Amboise, Indre-et-Loire, 4 January 1465),[6] father of King Louis XII of France.

- Philip, Count of Vertus (Asnières-sur-Oise, Val d'Oise, 21/24 July 1396 - Beaugency, Loiret, 1 September 1420).[6]

- John, Count of Angoulême (24 June 1399 – Château de Cognac, Charente, 30 April 1467),[6] grandfather of King Francis I of France.

- Margaret (4 December 1406 - Abbaye de Laguiche, near Blois, 24 April 1466), married Richard of Brittany, Count of Étampes.[14] She received the County of Vertus as a dowry.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Valentina Visconti, Duchess of Orléans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ^ Welch 1995, p. 30.

- ^ Gallo 1995, p. 54.

- ^ Rohr 2016, p. 54.

- ^ de Mesquita 1941, p. 329.

- ^ a b c de Mesquita 1941, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Adams 2010, p. 255.

- ^ Emerton 1917, p. 406.

- ^ Azzolini 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Sumption 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Henneman 2018, p. 140.

- ^ Knecht 2004, p. 52-53.

- ^ Veenstra 1998, p. 83.

- ^ a b c DeSilva 2015, p. 85.

- ^ Booton 2016, p. 141.

Sources

- Adams, Tracy (2010). The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Azzolini, Monica (2013). The Duke and the Stars: Astrology and Politics in Renaissance Milan. Harvard University Press.

- Booton, Diane E. (2016). Manuscripts, Market and the Transition to Print in Late Medieval Brittany. Taylor & Francis.

- DeSilva, Jennifer Mara (2015). The Sacralization of Space and Behavior in the Early Modern World: Studies and Sources. Routledge.

- Emerton, Ephraim (1917). The Beginnings of Modern Europe (1250-1450). Boston: Ginn & Co.

- Gallo, F. Alberto (1995). Music in the Castle: Troubadours, Books, and Orators in Italian Courts of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Centuries. University of Chicago Press.

- Henneman, John Bell (2018). Olivier de Clisson and Political Society in France Under Charles V and Charles VI. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Knecht, Robert (2004). The Valois: Kings of France 1328-1589. Hambledon Continuum.

- de Mesquita, Daniel Meredith Bueno (1941). Giangaleazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan (1351-1402): A Study in the Political Career of an Italian Despot. Cambridge at the University Press.

- Rohr, Zita Eva (2016). Yolande of Aragon (1381-1442) Family and Power: The Reverse of the Tapestry. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sumption, Jonathan (2016). The Hundred Years War. Vol. 4: Cursed Kings. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Veenstra, Jan R. (1998). Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France: Text and Contest of Laurens Pignon's "Contre le devineurs (1411)". Brill.

- Welch, Evelyn S. (1995). Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan. Yale University Press.