FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Sunnyvale, California | |

|---|---|

Downtown Sunnyvale | |

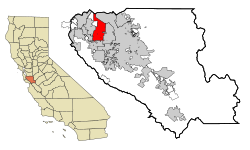

Location in Santa Clara County and the State of California | |

| Coordinates: 37°22′16″N 122°2′15″W / 37.37111°N 122.03750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Santa Clara |

| Incorporated | December 24, 1912[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[2] |

| • Mayor | Larry Klein[2] |

| • Vice mayor | Murali Srinivasan |

| • City Manager | Tim Kirby[3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 22.78 sq mi (58.99 km2) |

| • Land | 22.06 sq mi (57.14 km2) |

| • Water | 0.72 sq mi (1.86 km2) 3.09% |

| Elevation | 125 ft (38 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 155,805 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Santa Clara County 36th in California 176th in the United States |

| • Density | 6,800/sq mi (2,600/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 94085–94090 |

| Area codes | 408/669 and 650 |

| FIPS code | 06-77000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1656344, 2412009 |

| Website | sunnyvale |

Sunnyvale (/ˈsʌniveɪl, vəl/) is a city located in the Santa Clara Valley in northwest Santa Clara County in the U.S. state of California.

Sunnyvale lies along the historic El Camino Real and Highway 101 and is bordered by portions of San Jose to the north, Moffett Federal Airfield and NASA Ames Research Center to the northwest, Mountain View to the northwest, Los Altos to the southwest, Cupertino to the south, and Santa Clara to the east.

Sunnyvale's population was 155,805 at the 2020 census, making it the second most populous city in the county (after San Jose) the seventh most populous city in the San Francisco Bay Area, 36th in California, and 176th in the US.

As one of the major cities that make up California's high-tech area known as Silicon Valley, Sunnyvale is the birthplace of the video game industry, former location of Atari headquarters. Many technology companies are headquartered in Sunnyvale and many more operate there, including several aerospace/defense companies.

Sunnyvale was also the home to Onizuka Air Force Station, often referred to as "the Blue Cube" because of the color and shape of its windowless main building. The facility, previously known as Sunnyvale Air Force Station, was named for the deceased Space Shuttle Challenger astronaut Ellison Onizuka. It served as an artificial satellite control facility of the U.S. military until August 2010 and has since been decommissioned and demolished.

Sunnyvale is one of the few U.S. cities to have a single unified Department of Public Safety, where all personnel are trained as firefighters, police officers, and EMTs, so that they can respond to an emergency in any of the three roles.

History

The Santa Clara Valley was heavily populated by the indigenous Ohlone people when the Spanish first arrived in the 1770s.[8] However, following the arrival of the Spaniards, smallpox, measles, and other Old World diseases greatly reduced the Ohlone population.[8] While some of the Ohlone Native Americans died from diseases, others survived and were converted to Christian faith by the Spanish.[9] In 1777, Mission Santa Clara was founded by Franciscan missionary Padre Junipero Serra and was originally located in San Jose (near what is now the San Jose International Airport runway).[8]

1800s

In 1843, Rancho Pastoria de las Borregas was granted to Francisco Estrada and his wife Inez Castro.[11] Portions of the land given in this grant later developed into the cities of Mountain View and Sunnyvale.[12] Two years later, in 1844, another land grant was provided to Lupe Yñigo, one of the few Native Americans to hold land grants.[13][14] His land grant was first called Rancho Posolmi, named in honor of a village of the Ohlone that once stood in the area.[11]

Martin Murphy Jr. came to California with his father as part of the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party in 1844. In 1850, Martin Murphy Jr. bought a piece of Rancho Pastoria de las Borregas for $12,500. Murphy established a wheat farm and ranch named Bay View. Murphy had the first wood-frame house in Santa Clara County; it was shipped from New England. The house was demolished in 1961 but was reconstructed in 2008 as the Sunnyvale Heritage Park Museum. When he died in 1884, his land was divided among his heirs.[15][16]

In 1860, The San Francisco and San Jose Rail Road was allowed to lay tracks on Bay View and established Murphy Station. Lawrence Station was later established on the southern edge of Bay View.[citation needed]

In the 1870s, small fruit orchards replaced many large wheat farms, because wheat farming turned uneconomical due to county and property tax laws, imports and soil degradation.[17] In 1871, Dr. James M. Dawson and his wife Eloise (née Jones) established the first commercial fruit cannery in the county.[17][18][19][20] Fruit agriculture for canning soon became a major industry in the county. The invention of the refrigerated rail car further increased the viability of an economy based upon fruit. The fruit orchards became so prevalent that in 1886, the San Jose Board of Trade called Santa Clara County the "Garden of the World".

In the 1880s, Chinese workers made up roughly one third of the farm labor in Santa Clara County.[21] This percentage reduced over time after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. In the following decade, the 1890s, many immigrants from Italy, the Azores, Portugal, and Japan arrived to work in the orchards.[citation needed]

In 1897, Walter Everett Crossman bought 200 acres (810,000 m2) and began selling real estate. He advertised the area as "Beautiful Murphy" and later, in the 1900s, as "the City of Destiny". Also in 1897, Encinal School opened as the first school in Murphy. Previously, children in the town had to travel to Mountain View for school. The area also became known as Encinal.[citation needed]

1900s

In 1901, the residents of Murphy were informed they could not use the names Encinal or Murphy for their post office. Sunnyvale was given its current name on March 24, 1901. It was named Sunnyvale as it is located in a sunny region adjacent to areas with significantly more fog.[22]

Sunnyvale continued to grow and in 1904, dried fruit production began. Two years later, Libby, McNeill & Libby, a Chicago meat-packing company, decided to open its first fruit-packing factory in Sunnyvale. Today, a water tower painted to resemble the first Libby's fruit cocktail can label identifies the former site of the factory.

Also in 1906, the Joshua Hendy Iron Works relocated from San Francisco to Sunnyvale after the company's building was destroyed by fire after the 1906 earthquake. The ironworks was the first non-agricultural industry in the town. The company later switched from producing mining equipment to other products such as marine steam engines.

In 1912, the residents of Sunnyvale voted to incorporate, and Sunnyvale became an official city.[23]

Fremont High School first opened in 1923.[24] The year 2023 marked the school's 100 year anniversary.

In 1924, Edwina Benner was elected to her first term as mayor of Sunnyvale. She was the second female mayor in the history of the state of California.

In 1930, Congress decided to place the West Coast dirigible base in Sunnyvale after "buying" the 1,000-acre (4.0 km2) parcel of farmland bordering the San Francisco Bay from the city for $1.

This naval airfield was later renamed Naval Air Station Moffett and then Moffett Federal Airfield and is commonly called Moffett Field.

In 1939, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, the forerunner of NASA) began research at Ames Laboratory.

During World War II, the war economy began a change from the fruit industry to the high-tech industry in Santa Clara County. The Joshua Hendy Iron Works built marine steam engines, naval guns and rocket launchers to aid in the war effort. As the defense industry grew, a shortage of workers in the farm industry was created. Immigrants from Mexico came to Sunnyvale to fill this void of workers.

Following the war, the fruit orchards and sweetcorn farms were cleared to build homes, factories and offices.

In 1950, the volunteer fire department and the paid police department were combined into the department of public safety.[25]

In 1956, the aircraft manufacturer Lockheed moved its headquarters to Sunnyvale.[26]

Since then, numerous high-tech companies have established offices and headquarters in Sunnyvale, including Advanced Micro Devices and Yahoo.

The first prototype of Atari's coin-operated Pong, the first successful video game, was installed in Sunnyvale in August 1972, in a bar named Andy Capp's Tavern,[27][28] now Rooster T. Feathers.[29] Atari's headquarters were located at 1196 Borregas Avenue in north Sunnyvale.

By 2002, the few remaining orchards had been replaced with homes and shops. However, there are still city-owned orchards, such as the Heritage Orchard next to the Sunnyvale Community Center.

In 1979, an indoor mall called Sunnyvale Town Center opened in what used to be a traditional downtown shopping district. After years of successful operation, the mall started to decline in the 1990s. After numerous changes in plans and ownership, the mall was demolished in 2007.

2000s

Sunnyvale celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary on August 25, 2012.

According to the Bay Area Census, there was a total population of 130,885 people in households and 875 people in group quarters in 2000.[30] In 2023, the city has a population of 145,302 residents; however, the city's population is declining at a rate of −6.77% since the 2020 census, which claimed that Sunnyvale had a population of 155,860 residents.[31]

Downtown development

In November 2009, previously closed portions of the main streets in downtown Sunnyvale were reopened as part of the ongoing downtown redevelopment of the Sunnyvale Town Center mall, marking the first time in over three decades that those street blocks have been open to vehicle and pedestrian traffic. Part of the project involved building new apartment buildings, however during the Great Recession the property was repossessed by Wells Fargo in 2009; the developer countersued, leaving the project in legal limbo through 2015.[32]

The two office buildings are now fully occupied by Uber. Mixed-use developments have been built at the former Town and Country location near the Plaza del Sol just north of Murphy Avenue. By mid 2015, new multistory apartment complexes had opened, including a number of ground-floor businesses, and the lawsuit against Wells Fargo was resolved in the bank's favor. The development was sold to Sares Regis in late 2016.[33] Redwood Square reopened as a park in 2017.[34] Many apartments are occupied, and more are being completed in 2020. A Whole Foods Market and AMC Theatres multiplex opened in October 2020.[35]

Major businesses

In the 2010s, Sunnyvale became home to operations from numerous major technology companies including Apple, LinkedIn (now headquartered in Sunnyvale),[36] Google, Amazon, Meta, Walmart Labs, and 23andMe.

Google announced major development plans in the Moffett Park area in 2017 adjacent to Moffett Field,[37] with these offices ultimately opening in 2022.[38] In addition, Amazon and Meta began leasing buildings in Sunnyvale in 2017[39] and 2021,[40] respectively.

Geography

Sunnyvale is located at 37°22′7.56″N 122°2′13.4″W / 37.3687667°N 122.037056°W.[41]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 22.7 sq mi (58.8 km2), of which, 22.0 sq mi (56.9 km2) of it is land and 0.69 sq mi (1.8 km2) of it (3.09%) is water. Its elevation is 130 feet above sea level.

Climate

Like most of the San Francisco Bay Area, Sunnyvale has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb), with cool, moist winters and warm, very dry summers. Average daytime summer temperatures are in the high 70s, and during the winter, average daytime high temperatures rarely stay below 50 °F (10 °C). Snowfall is rare, but on January 21, 1962, and February 5, 1976, measurable snowfall occurred in Sunnyvale and most of the San Francisco Bay Area. Sunnyvale was briefly hit by tornadoes in 1951 and 1998, but otherwise they are extremely rare.[42][43][44][45]

| Climate data for Sunnyvale, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

84 (29) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

75 (24) |

107 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59 (15) |

62.2 (16.8) |

65.6 (18.7) |

70 (21) |

74.3 (23.5) |

78.8 (26.0) |

80.7 (27.1) |

80.8 (27.1) |

80.1 (26.7) |

74.3 (23.5) |

64.7 (18.2) |

58.6 (14.8) |

70.8 (21.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41.1 (5.1) |

43.5 (6.4) |

45.4 (7.4) |

47.1 (8.4) |

50.7 (10.4) |

54.1 (12.3) |

56.5 (13.6) |

56.4 (13.6) |

55 (13) |

50.8 (10.4) |

44.8 (7.1) |

41 (5) |

48.9 (9.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 21 (−6) |

24 (−4) |

22 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

41 (5) |

44 (7) |

41 (5) |

34 (1) |

15 (−9) |

20 (−7) |

15 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.30 (84) |

3.56 (90) |

2.57 (65) |

1.15 (29) |

0.52 (13) |

0.12 (3.0) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.90 (23) |

2.03 (52) |

3.10 (79) |

17.52 (444.81) |

| Source: Northwest Climate Toolbox[46] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 3,094 | — | |

| 1940 | 4,373 | 41.3% | |

| 1950 | 9,829 | 124.8% | |

| 1960 | 59,898 | 509.4% | |

| 1970 | 95,976 | 60.2% | |

| 1980 | 106,618 | 11.1% | |

| 1990 | 117,229 | 10.0% | |

| 2000 | 131,760 | 12.4% | |

| 2010 | 140,081 | 6.3% | |

| 2020 | 155,805 | 11.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[47] | |||

The 2020 United States census[48] reported that Sunnyvale had a population of 155,805. The population density was 6,596 inhabitants per square mile (2,547/km2).[49] The racial makeup of Sunnyvale was 46,551 (29.9%) White, 2,228 (1.4%) African American, 1,081 (0.7%) Native American, 77,842 (49.9%) Asian, 491 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 14,181 (9.1%) from other races, and 13,431 (8.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 25,372 persons (16.3%). Non-Hispanic Whites were 27.8% of the population in 2020,[50] compared to 74.7% in 1980.[51]

There were 59,567 households,[52] out of which 16,133 (27%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 31,557 (53.0%) were married opposite-sex couples living together, 4,069 (6.8%) had a female householder with no husband present, 2,908 (4.9%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 3,382 (5.7%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 657 (1.1%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 14,970 households (25.1%) were made up of individuals, and 5.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54. There were 38,750 families (65.0% of all households); the average family size was 3.09.

The population was spread out, with 32,453 people (20.8%) under the age of 18, 9,641 people (6.2%) aged 18 to 24, 57,977 people (37.2%) aged 25 to 44, 34,330 people (22.0%) aged 45 to 64, and 20,683 people (13.2%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 109.3 males.

There were 63,065 housing units, of which 45.8% were owner-occupied, and 54.2% were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.1%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.3%. 72,485 people (46.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 80,220 people (51.5%) lived in rental housing units.

2020

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[53] | Pop 2010[54] | Pop 2020[55] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 61,221 | 48,323 | 43,281 | 46.46% | 34.50% | 27.78% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 2,790 | 2,533 | 2,134 | 2.12% | 1.81% | 1.37% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 362 | 292 | 187 | 0.27% | 0.21% | 0.12% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 42,296 | 57,012 | 77,552 | 32.10% | 40.70% | 49.78% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 393 | 594 | 439 | 0.30% | 0.42% | 0.28% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 304 | 381 | 839 | 0.23% | 0.27% | 0.54% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 4,004 | 4,429 | 6,001 | 3.04% | 3.16% | 3.85% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 20,390 | 26,517 | 25,372 | 15.48% | 18.93% | 16.28% |

| Total | 131,760 | 140,081 | 155,805 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Economy

Companies based in Sunnyvale include Infinera, Fortinet, Intuitive Surgical, Juniper Networks, LinkedIn, Proofpoint, Inc., Matterport, Inc., and Trimble Inc.

In the 1950s to the 1970s, Sunnyvale had chrysanthemum farms.[56][57] Takanoshin Domoto, by 1885 was growing chrysanthemums and carnations at their small nursery in Oakland.[58] Bay Area Chrysanthemum Growers Association (BACGA) was established in 1956.[59][60][61][62] The 1991 Andean Trade Preference Act “war on drugs” made Colombian, Peruvian, Bolivian and Ecuadorian flowers tariff-free.[58] Half Moon Bay and Redwood City were also chrysanthemum business locations.[63][64]

Largest employers

According to the city's 2023 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[65] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13,644 | |

| 2 | Apple Inc. | 12,831 |

| 3 | 5,347 | |

| 4 | Altaba | 3,877 |

| 5 | Amazon.com Services | 3,748 |

| 6 | Lockheed Martin Space | 3,576 |

| 7 | Applied Materials | 3,389 |

| 8 | Intuitive Surgical | 3,373 |

| 9 | Cepheid | 3,334 |

| 10 | A2Z Development Center | 3,250 |

Government and politics

The City of Sunnyvale uses the council–manager form of government,[66] with a city council consisting of seven members elected to fill individual seats. Starting in November 2020, the mayor is directly elected to a four-year term in a city-wide election. The six council members are elected to four year terms from six districts in even-year elections. The vice-mayor is selected from the six city council members by the mayor and city council, serving a one-year term.[67][2] The city council hires a city manager to run the day-to-day operations of the city government.[66]

Sunnyvale is the largest city in the United States that uses a consolidated department of public safety, with sworn officers who are fully cross-trained to perform police, firefighting, and emergency medical services. Officer assignments are rotated annually, with some specialist assignments lasting up to five years. Sunnyvale has had a consolidated DPS since 1950.[68]

In the California State Legislature, Sunnyvale is in the 13th Senate District, represented by Democrat Josh Becker, and in the 24th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Alex Lee.[69]

In the United States House of Representatives, Sunnyvale is in California's 17th congressional district, represented by Democrat Ro Khanna.[70]

| Date | # of Registered Voters |

|---|---|

| August 16, 2016 | 56,030[71] |

| June 5, 2018 | 58,542[72] |

| November 6, 2018 | 61,144[73] |

Education

For elementary and middle schools, most of the city is in the Sunnyvale School District, while some parts are in the Cupertino Union School District, the Santa Clara Unified School District, and the Mountain View Whisman Elementary School District.[74]

For high schools, most of the city is in the Fremont Union High School District (the parts that are part of the Sunnyvale School District or Cupertino Union School District for primary schools), and those areas of Sunnyvale are divided between Fremont High School and Homestead High School.[75] Some parts of the city are in the Santa Clara Unified School District.

French American School of Silicon Valley (FASSV, French: École franco-américaine de la Silicon Valley) is a private elementary school in Sunnyvale, which opened in 1992.[76] It is recognized as a French international school by the AEFE.[77]

Library services for the city are provided by the Sunnyvale Public Library, located at the Sunnyvale Civic Center.

| Elementary schools | Middle schools |

|---|---|

| Ellis Elementary | Columbia Middle |

| Vargas Elementary | Sunnyvale Middle |

| Cherry Chase Elementary | |

| Bishop Elementary | |

| San Miguel Elementary | |

| Fairwood Elementary | |

| Lakewood Elementary | |

| Cumberland Elementary |

| Elementary Schools | Middle Schools | High Schools | District abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pomeroy Elementary | Peterson Middle School | Adrian Wilcox High School | SCUSD (Santa Clara) |

| Braly Elementary | |||

| Nimitz Elementary | Cupertino Middle School | Fremont High School | CUSD (Cupertino) + FUHSD |

| Stocklmeir Elementary | |||

| West Valley Elementary |

Private schools in Sunnyvale[79]

- FASSV (French American School of Silicon Valley)

- Stratford School

- The King's Academy (Religious)

- Challenger School

- Rainbow Montessori

- Helios School

- Jazmin Chandler

- Resurrection School (Religious)

- Silicon Valley Academy (Religious)

- South Peninsula Hebrew day school (Religious)

- Sunnyvale Christian School (Religious)

Neighborhoods

The southern half of Sunnyvale is predominantly residential, while most of the portion of Sunnyvale north of Highway 237 is zoned for industrial use.[80]

Within this southern half are several neighborhoods that account for a large number of Eichler homes throughout residential Sunnyvale. More specifically, there are 16 housing tracts containing over 1100 Eichler homes.[81]

The far eastern section of El Camino Real in Sunnyvale has a significant concentration of businesses owned by Indian immigrants.[82]

Parks

There are 476 acres of parks in the Sunnyvale area.[83] These include Las Palmas Park, Ortega Park, Seven Seas Park, Fair Oaks Park, Washington Park near downtown, two public golf courses, and Baylands Park,[84] site of the annual Linux Picnic.

Charles Street Gardens,[85] Sunnyvale's oldest and largest community garden, is located adjacent to Sunnyvale's Public Library. In 2017 the Santa Clara Unified School District took over operation of Full Circle Farm Sunnyvale, which leased the land from the district, and plan to focus the farm on education.[86]

Transportation

Several major roads and freeways go through Sunnyvale:

Interstate 280 (Junipero Serra Freeway)

Interstate 280 (Junipero Serra Freeway) U.S. Route 101

U.S. Route 101 State Route 82 (El Camino Real)

State Route 82 (El Camino Real) State Route 85 (Stevens Creek Freeway)

State Route 85 (Stevens Creek Freeway) State Route 237 (Southbay Freeway)

State Route 237 (Southbay Freeway)

Public transportation

Sunnyvale is served by Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (light rail and buses) and by Caltrain commuter rail. Two Caltrain stations are located in Sunnyvale: the Sunnyvale station in the Heritage District downtown, and the Lawrence station in eastern Sunnyvale, north of the Ponderosa neighborhood.

Bicycle

Sunnyvale has been listed by the League of American Bicyclists as a bronze-level Bicycle Friendly Community.[87]

The Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee advises the city council on the continued development of the bicycle plan for the city.

Airports

For commercial passenger air travel, Sunnyvale is served by three nearby international airports:

- Norman Y. Mineta San Jose International Airport (SJC), 9.5 miles from downtown Sunnyvale by car. It is also accessible by Caltrain, VTA light rail, and VTA bus. Caltrain and light rail stations require a transfer to a free shuttle bus to get to the airport terminal.

- San Francisco International Airport (SFO), 27.7 miles by car. SFO is transit accessible from Sunnyvale via Caltrain and Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART).

- Metropolitan Oakland International Airport (OAK), 37.5 miles by car. Access to Oakland airport by public transit is possible via multiple transfers.

Crime

Sunnyvale has consistently ranked as one of the safest ten cities (for cities of similar size) in the United States according to the FBI's crime reports. From 1966 to at least 2004, Sunnyvale never placed below fifth in safety rankings among U.S. cities in its population class.[88] In 2005, Sunnyvale ranked as the 18th-safest city overall in the U.S., according to the Morgan Quitno Awards.[89] In 2009, Sunnyvale was ranked 7th in U.S. by Forbes Magazine in an analysis of America's safest cities.[90][91] In 2018, Sunnyvale was named the safest city by SmartAsset.com for the third year in a row.[92]

Gangs

According to Sunnyvale's Department of Public Safety, confirmed gang members make up less than one percent of the population, although 95% of the crime is gang on gang violence.[93] Sunnyvale's Gang Task-force agency as well as the FBI note three main gangs that exist in Sunnyvale, thrice allying to either Sureño or Norteño families, one existing since the 1960s.[94][95]

Mass shooting

On February 16, 1988, Richard Farley shot 11 people, killing seven of them, at his former employer ESL Incorporated in north Sunnyvale, across Borregas Avenue from Atari. The 1993 made-for-television film I Can Make You Love Me starring Brooke Shields and Richard Thomas was based on the event.

Folklore

A long-standing legend of Sunnyvale is of a ghost that haunts the town's Toys 'R' Us store (now REI). A purported psychic, Sylvia Browne, claimed to have made contact with the ghost on the 1980 TV show That's Incredible! and named him Johnny Johnson. This story was also explored in a 1991 episode of Haunted Lives: True Ghost Stories. Browne stated that he had been a Swedish preacher who worked as a farm hand in the orchard where the toy store now stands and that he bled to death from an accidental, self-inflicted axe injury to his leg.[96][97][98][99]

Notable people

- Tony Anselmo, animator and voice of Donald Duck[100]

- Robert Hawkins, artist and painter[101]

- Ashleigh Aston Moore, actress[102]

- Teri Hatcher, actress[103]

- Imran Khan, Bollywood actor[104]

- Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Inc.[105]

- Lee Pelekoudas, Seattle Mariners interim general manager, raised in Sunnyvale.[106]

- Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple Inc.[105]

- Richard Farley, mass murderer[107]

- Arthur Davis, animator and director[108]

- Timothy Linh Bui, filmmaker[109]

- Tony Bui, film director[110]

- Steve Kloves, American screenwriter, film director and producer

- Antwon, hip-hop artist[111]

- Brian MacLeod, musician[112]

- The Orange Peels, musical group[113]

- Juju Chang, television personality[114]

- Martin Ford, entrepreneur, author[115]

- Jeff Goodell, writer[116]

- Michael S. Malone, multiple talents[117]

- Amy Tan, novelist[105]

- Tully Banta-Cain professional football player[118]

- Brian Boitano, figure skater[100]

- Benny Brown, runner[119]

- Sean Dawkins, NFL player, lived in Sunnyvale[120] while attending Homestead High School in Cupertino.

- Penny Deen, swimmer and coach[100]

- Francie Larrieu-Smith, track and field athlete[118]

- Peter Ueberroth, Major League Baseball Commissioner 1984–89[121]

- Bill Green, former U.S. and NCAA record holder in Track and Field, 5th place in the hammer throw at the 1984 Olympic Games

- Chris Pelekoudas, Major League Baseball umpire, lived and died in Sunnyvale.[106]

- Troy Tulowitzki, Major League Baseball player, graduated from Fremont High School

- Andrew Fire, 2006 Nobel Laureate in medicine[105]

- Landon Curt Noll, astronomer, cryptographer and mathematician[122]

- Mark Rober, NASA JPL employee 2004–2011, current scientific YouTuber

- Joe Prunty, NBA assistant coach for the Atlanta Hawks

Twin towns – sister cities

Until 1970, Sunnyvale had a Sister City relationship with Chillán, Chile. In 2013, the city entered into a three-year Friendly Exchange Relations Agreement with Iizuka, Japan; in July 2016 the city council voted to change this to a Sister City relationship.[123]

See also

References

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c "City Council". City of Sunnyvale. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ "City of Sunnyvale Press Release". City of Sunnyvale. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Sunnyvale". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ "Sunnyvale (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates Tables". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Historical Information – Mission Santa Clara de Asís". Santa Clara University. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Admin (September 5, 2019). "The History of Sunnyvale, California". Best Property Management Company San Jose I Intempus Realty, Inc. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Heritage Resources Inventory" (PDF). City of Sunnyvale Heritage Preservation Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Early Santa Clara Ranchos, Grants, Patents and Maps". The CAGenWeb Project. Archived from the original on January 2, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Geographic Names Information System". The National Map. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ DeBolt, Daniel (August 5, 2013). "One woman's indelible mark on Silicon Valley". Mountain View Voice. Embarcadero Media Foundation. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "Portrait of Lupe Yñigo". SCU Digital Collections. Santa Clara University. Archived from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "The Murphy Story". Sunnyvale Heritage Park Museum. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Ignoffo, Mary Jo (1955). Sunnyvale: From the City of Destiny to the Heart of Silicon Valley. Cupertino, California: California History Center & Foundation. pp. 6–11. ISBN 9780935089172. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "1870–1918, City Expansion". San Jose History. November 7, 2013. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Feroben, Carolyn. "James M. Dawson – Pioneer fruit packer, Santa Clara Valley, 1871". The Valley of Heart's Delight, Santa Clara County Biography Project.

- ^ "Cannery Tour".

- ^ "Cannery Life: Del Monte in the Santa Clara Valley".

- ^ Chan, Sucheng (1989). This Bittersweet Soil: The Chinese in California Agriculture, 1860–1910. University of California Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0520067370. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Capace, Nancy (1999). Encyclopedia of California. North American Book Dist LLC. Page 447. ISBN 9780403093182.

- ^ "Sunnyvale | California, United States | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "History & School Culture –". fhs.fuhsd.org. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy M.; Weiss, Alexander; Grammich, Clifford (August 2012). Public Safety Consolidation: What Is It? How Does It Work? (PDF). BOLO (Report). Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. pp. 4–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Baker, David R. (September 15, 2006). "Where science takes flight / Lockheed marks 50 years in Sunnyvale". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Pong, Arcade Video game by Atari, Inc. (1972)". Arcade-history.com. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Scott (1984). Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-011543-5. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ "City of Sunnyvale Heritage Bicycle Tours" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Bay Area Census – City of Sunnyvale". bayareacensus.ca.gov. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Sunnyvale, California Population 2023". worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Donato-Weinstein, Nathan (August 13, 2015). "Sunnyvale Town Center officially for sale as litigation cloud lifts". The Business Journals. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Druzin, Bryce (September 29, 2016). "Sunnyvale Town Center deal closes for $100 million". The Business Journals. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Kezra, Victoria (November 27, 2017). "Redwood Square opens in downtown Sunnyvale". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Avalos, George (October 29, 2020). "Whole Foods, AMC Theaters open in downtown Sunnyvale". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2021 – via LinkedIn.

- ^ Avalos, George (February 6, 2018). "Google's Sunnyvale ambitions prompt merchants' worries and warnings". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Forestieri, Kevin (May 17, 2022). "Google opens the doors on its massive Bay View campus next to NASA Ames". Archived from the original on May 7, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ Avalos, George (December 15, 2017). "Big Amazon campus sprouts in Sunnyvale, Silicon Valley footprint widens". Archived from the original on May 9, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ Avalos, George (December 1, 2021). "Meta, formerly Facebook, leases huge tech campus in Sunnyvale". Archived from the original on December 29, 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Sunnyvale and Los Altos, CA Tornadoes". San Francisco State University, Department of Geosciences. May 4, 1998. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Berton, Justin; Enders, Steve (May 6, 1998). "Hit and Run: Freak tornado injures no one, but leaves behind costly damage". The Sun. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Monteverdi, John P.; Blier, Warren; Stumpf, Greg; Pi, Wilfred; Anderson, Karl (November 2001). "First WSR-88D Documentation of an Anticyclonic Supercell with Anticyclonic Tornadoes: The Sunnyvale–Los Altos, California, Tornadoes of 4 May 1998". Monthly Weather Review. 129 (11): 2805. Bibcode:2001MWRv..129.2805M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2001)129<2805:FWDOAA>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Coile, Zachary; Emily Gurnon (February 6, 1998). "Storm knocks out power to thousands in Bay Area; Marin commuters cut off by U.S. 101 closure". THE STORMS OF '98. Archived from the original on March 31, 2003. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Northwest Climate Toolbox". Climate Toolbox. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Sunnyvale city". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Sunnyvale, California Population 2023". worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ "Sunnyvale (city), California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell; Jung, Kay (February 2005). "California – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Sunnyvale city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Sunnyvale city, California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Sunnyvale city, California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Chow, Mike (November 30, 2009). "Sunnyvale history: Chrysanthemum business in 1950s involved the entire family". The Mercury News. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Hartmann, Ilka. "Bay Area Chinese Communities: Sunnyvale". Ilka Hartmann Photography - ilkahartmann.squarespace.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2024. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Japanese Nursery Industry in the Bay Area". Japanese American Nurseries. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Fuentes, Maricella (July 31, 2024). "Chinese Farmworkers". Veggielution. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "11/22/24 CHCP Corsage Workshop". Chinese Historical & Cultural Project - chcp.org. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "California's immigrant farmers squeezed by Silicon Valley success". The World. PRX. September 24, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Takahashi, Melina (February 22, 1998). "Interviewee: Masayo (Yasui) Arii". REgenerations Oral History Project: Rebuilding Japanese American Families, Communities, and Civil Rights in the Resettlement Era : San Jose Region: Volume IV. Online Archive of California. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Clifford, Jim (December 2, 2019). "Redwood City Was the "Chrysanthemum Capital of the World"". Climate Online. Redwood City. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Calic, Dan (November 5, 2021). "Flower Power in Redwood City". Redwood City Pulse. Redwood City. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Annual Comprehensive Financial Report: For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2023". City of Sunnyvale, California. p. 232. Archived from the original on June 2, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ a b "City Governance". City of Sunnyvale. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Sunnyvale City Clerk: Elections". Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Romney, Lee (January 1, 2013). "Cross-training of public safety workers attracting more interest". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ "California's 17th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "ROV Post-Election Report Aug 16 2016 Special Election" (PDF). sccgov.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "Registrar of Voters Post-Election Report" (PDF). sccgov.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ "Registrar of Voters Post-Election Report" (PDF). sccgov.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS – SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Santa Clara County, CA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 1 (PDF p. 2/5). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ * "Fremont High School" (PDF). Fremont Union High School District. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- "Homestead High School" (PDF). Fremont Union High School District. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "Our School". French American School of Silicon Valley. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "École franco-américaine de la Silicon Valley" (in French). AEFE. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "SESD, our schools". SESD, our schools. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Private Schools in sunnyvale". privateschoolreview.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "City of Sunnyvale Zoning Map" (PDF). City of Sunnyvale. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Sunnyvale Real Estate | Eichler Homes | Tract Housing | Boyenga Team". siliconvalleyrealestate.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (May 2, 2004). "A 'Little Madras' here too ..." The Hindu. Archived from the original on May 11, 2004. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "City of Sunnyvale: Parks". sunnyvale.ca.gov. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "Parks & Facilities Map". City of Sunnyvale. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Charles Street Gardens". charlesstreetgardens.org. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Kezra, Victoria (September 26, 2017). "Farm at Sunnyvale school will focus on education". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Current Bicycle Friendly Communities Spring 2016" (PDF). BikeLeague.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "City of Sunnyvale News Release No. 11-08". City of Sunnyvale. November 22, 2004. Archived from the original on February 15, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "11th Annual America's Safest (and Most Dangerous) Cities". Morgan Quitno Awards. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ O'Malley, Zack (October 26, 2009). "In Depth: America's Safest Cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "America's Safest Cities". Bay Area Indo American. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Kezra, Victoria (January 2, 2018). "Sunnyvale named safest city in the U.S. for the third year". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Alia (August 7, 2012). "Sunnyvale DPS discusses topic of gangs at neighborhood meeting". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Myers, Reid (August 6, 2012). Sunnyvale Neighborhoods Association Meeting, August 6, 2012 (PDF) (Report). Sunnyvale Neighborhood Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "2011 National Gang Threat Assessment – Emerging Trends". FBI. 2011. Archived from the original on June 19, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Haunted Toys 'R' Us Archived August 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Snopes.com, October 29, 1998; citing Gina Boubion, Ghost Lets Playful Side Show in Pranks at Haunted Toy Store, The Houston Chronicle, April 26, 1993, p. A2; and Dan Koeppel, Ghost Sightings Aren't Spooking Sales at Toys 'R' Us, Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1991, p. C8

- ^ "Toys 'R Us Ghost". Ghost Research Society. Archived from the original on August 18, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Dowd, Katie (March 13, 2018). "Would the death of Toys R Us kill off this famous South Bay ghost story?". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ May, Patrick (March 23, 2018). "This Bay Area Toys R Us is about to vanish like a ghost". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Who's Who in Santa Clara Unified?". Santa Clara County Unified School District. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Robert Hawkins Biography". Artnet.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Lentz III, Harris M. (2008). Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2007: Film, Television, Radio, Theatre, Dance, Music, Cartoons and Pop Culture. McFarland. p. 258. ISBN 978-0786451913. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Webby, Sean (August 21, 2008). "Child molester dies in custody". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Thekkepat, Shiva Kumar (September 18, 2015). "Imran Khan: the New Age hero?". Friday. Al Nisr Publishing LLC. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Alia (July 12, 2012). "Centennial Series: Sunnyvale celebrity and the hometown folks who made it big". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Stone, Larry (June 27, 2008). "Mariners' interim GM Lee Pelekoudas: A life in baseball". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Morain, Dan; Stein, Mark A. (February 18, 1988). "Unwanted Suitor's Fixation on Woman Led to Carnage". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (2006). Who's who in Animated Cartoons: An International Guide to Film & Television's Award-winning and Legendary Animators. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 60. ISBN 978-1557836717.

- ^ Boudreau, John (November 9, 2012). "Q&A: Vietnamese-American filmmaker Timothy Linh Bui explores his roots and craft". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Bayor, Ronald H. (2011). Multicultural America: An Encyclopedia of the Newest Americans. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 2268. ISBN 978-0313357879. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Weinstock, Tish (March 17, 2014). "A First Date With... Antwon". Vice Noisey. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Musicians". warningshortfilm.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Harrington, Jim (July 19, 2013). "Harrington: Orange Peels, the Sunnyvale indie-rock band, return with ambitious new album". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Chang, Juju (April 29, 2017). "Reporter's notebook: Riots or uprising? 25 years since the Rodney King verdict, a Korean American story". United States: ABC News. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ O'Brien, Matt (June 12, 2015). "Q&A: Martin Ford, on the robots coming for your job". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Goodell, Jeff (2001). Sunnyvale: The Rise and Fall of a Silicon Valley Family. Vintage. ISBN 978-0679776383.

- ^ Cassidy, Mike (December 5, 2013). "Getting to the truth of Silicon Valley". Santa Clara Magazine. Santa Clara University (SCU). Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Kezra, Victoria (January 20, 2016). "Sunnyvale Schools: From Super Bowl rings to Olympic dreams, Fremont High honors its first Hall of Famers". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Reid, John (September 23, 2015). "Prep Lookout: Los Altos High's class of 1970 was special". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Allen, Percy (June 9, 1999). "Dawkins Runs A Route From Personal Tragedy – Seahawk Receiver Attempts To Deal With Mother's Death". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Purdy, Mark (November 8, 2011). "Mark Purdy: Peter Ueberroth is the most influential American sports figure of the last 50 years". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ McRae, Steve (July 11, 2017). "Landon Curt Noll, computer scientist and 8 world records holder, joins the Great Debate Community". Great Debate Community. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Kezra, Victoria (July 7, 2016). "Sunnyvale gains a new sister city in Iizuka, Japan". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.