FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

This list of ancient watermills presents an overview of water-powered grain-mills and industrial mills in classical antiquity from their Hellenistic beginnings through the Roman imperial period.

The watermill is the earliest instance of a machine harnessing natural forces to replace human muscular labour (apart from the sail).[3] As such, it holds a special place in the history of technology and also in economic studies where it is associated with growth.[4]

The initial invention of the watermill appears to have occurred in the hellenized eastern Mediterranean in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great and the rise of Hellenistic science and technology.[5] In the subsequent Roman era, the use of water-power was diversified and different types of watermills were introduced. These include all three variants of the vertical water wheel as well as the horizontal water wheel.[6] Apart from its main use in grinding flour, water-power was also applied to pounding grain,[7] crushing ore,[8] sawing stones[9] and possibly fulling and bellows for iron furnaces.[10]

An increased research interest has greatly improved our knowledge of Roman watermill sites in recent years. Numerous archaeological finds in the western half of the empire now complement the surviving documentary material from the eastern provinces; they demonstrate that the breakthrough of watermill technology occurred as early as the 1st century AD and was not delayed until the onset of the Middle Ages as previously thought.[11] The data shows a wide spread of grain-mills over most parts of the empire, with industrial mills also being in evidence in both halves.[12] Although the prevalence of grain-mills naturally meant that watermilling remained a typically rural phenomenon, it also rose in importance in the urban environment.[13]

The data below spans the period until ca. 500 AD. The vast majority dates to Roman times.

Earliest evidence

Below the earliest ancient evidence for different types of watermills and the use of water-power for various industrial processes. This list is continued for the early Middle Ages here.

| Date | Water-powered mill types | Reference (or find spot) | Modern Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Possibly first half of 3rd century BC | Horizontal-wheeled mill [5] | Byzantium (assigned place of invention) | Turkey |

| Possibly c. 240 BC | Vertical-wheeled mill [5] | Alexandria (assigned place of invention) | Egypt |

| Before 71 BC? | Grain-mill ("watermill") [14] | Strabon, XII, 3, 30 C 556 | Turkey |

| 40/10 BC | Undershot wheel mill [15] | Vitruvius, X, 5.2 | Unspecified |

| 40/10 BC | Possible kneading machine [16] | Vitruvius, X, 5.2 | Unspecified |

| 20 BC/10 AD | Overshot wheel mill [17] | Antipater of Thessalonica, IX, 418.4–6 | Unspecified |

| c. 70 AD | Trip hammer[7] | Pliny, Naturalis Historia, XVIII, 23.97 | Italy |

| 73/4 AD | Possible fulling mill[18] | Antioch | Syria |

| 2nd century AD | Multiple mill complex [19] | Barbegal mill | France |

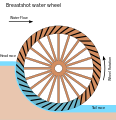

| Late 2nd century AD | Breastshot wheel mill [20] | Les Martres-de-Veyre | France |

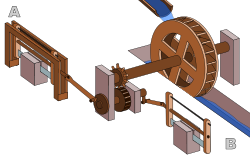

| Second half of 3rd century AD | Sawmill; crank and connecting rod system with gear train [21] | Hierapolis sarcophagus | Turkey |

| Late 3rd or early 4th century AD | Turbine mill [22] | Chemtou and Testour | Tunisia |

| Late 3rd or early 4th century AD | Possible tanning mill [23] | Saepinum | Italy |

| ? | Possible furnace[8] | Marseille | France |

-

Undershot water wheel

-

Breastshot water wheel

-

Overshot water wheel

Written sources

In the following, literary, epigraphical and documentary sources referring to watermills and other water-driven machines are listed.

| Reference | Location | Date | Type of evidence | Comments on |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammianus Marcellinus, 18.8.11 [24] | Amida | 359 AD | History | Multiple mill complex |

| Antipater of Thessalonica, IX, 418.4–6 [20] | Unspecified | 20 BC/10 AD | Poem | Earliest reference to overshot wheel mill [20] |

| Ausonius, Mosella, 362–364 [25] | Ruwer river | c. 370 AD | Poem | Water-powered marble saws and grain-mills |

| Beroea[26] | Macedonia | 2nd century AD | Decree | Tax revenue from watermills |

| Cedrenus, Historiarum compendium, p. 295 [516] [27] | India | c. 325 AD | History | |

| CG-CI, pp. 86–90, no. 41 [28] | Corinth | 6th century AD | ||

| CIL, III, 5866 [29] | Günzburg | 1st/3rd century AD | Epigraphy | Miller’s guild [30] |

| CIL, III, 14969, 2 [31] | Promona | 1st/4th century AD | Epigraphy | |

| CIL, VI, 1711 [32] | c. 480 AD | Epigraphy | ||

| Codex Justinianus, XI, 43, 10, 3 [28] | Constantinople | 474/491 AD | Legal code | |

| Codex Theodosianus, XIV, 15.4 [32] | 398 AD | Legal code | ||

| Diocletian, XV, 54 [30] | 301 AD | Price edict | ||

| Euchromius, VII, pp. 138–9, no. 169 [33] | Sardis | 4th to 5th/6th century AD | Epigraphy | Watermill engineer |

| Gregory of Nyssa, In Ecclesiasten, III, 656A Migne [34] | c. 370/390 AD | Theology | Water-powered marble saws? [35] | |

| John Cassian, Conlationes Patrum, I, 18 [36] | 426 AD? | Theology | ||

| Letter [37] | Egypt | 5th century AD | Possible watermill | |

| Libanius, Or. 4.29 [26] | Antioch | 380s AD | Rhetoric | Tax on watermills |

| MAMA, VII, p. 70, no. 305, lines 29–32 [34] | Orcistus | c. 329 AD [38] | Epigraphy | Town privilege |

| Mar. Aur. Apollodotos Kalliklianos [39] | Hierapolis | Second half of 3rd century AD | Epigraphy | Member of guild of water-millers |

| Molitor [30] | Châteauneuf | 1st century AD | Epigraphy | |

| Palladius, Opus agriculturae, I, 41, (42) [40] | 4th/5th century AD | Treatise | Use of waste water to drive watermills | |

| Pliny, Naturalis Historia, XVIII, 23.97 [41] | Italy | c. 70 AD | Encyclopedia | Water-powered pestles [42] |

| Sabinianus I, 18 | c. 450 AD | Hagiography | ||

| Strabon, XII, 3, 30 C 556 [28] | Cabira | Before 71 BC? [43] | Geography | |

| Talmud, Shabbat, I, 5 [44] | Before 70 AD? | |||

| Two inscriptions [18] | Antioch | 73/4 AD | Epigraphy | Possibly fulling mills |

| Visigothic Code, VII, 2, 12 and VIII, 4, 29–30 [41] | Late 5th century AD | Legal code | ||

| Vita S. Romani abbatis, 17–18 [45] | c. 450 AD | Hagiography | Water-powered pestles [42] | |

| Vitruvius, X, 5.2 [46] | 40/10 BC | Engineering | Earliest description of undershot wheel mill [46] | |

| Vitruvius, X, 5.2 [16] | 40/10 BC | Engineering | Possible kneading machine |

Graphical representations

This section deals with depictions of watermills which are preserved in ancient paintings, reliefs, mosaics, etc.

| Place (or object) | Country | Date | Type of evidence | Identification/Remains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coemeterium Maius at Rome[47] | Italy | Late 3rd century AD? | Wall painting | |

| Utica[48] | Tunisia | 4th century AD | Mosaic [A 1] | |

| Great Palace of Constantinople[49] | Turkey | c. 450/500 AD | Mosaic | One probable and one possible representation |

| Hierapolis sarcophagus[9] | Turkey | Second half of 3rd century AD | Relief | Water-powered stone sawmill; earliest known crank and connecting rod system [2] |

Archaeological finds

Watermill sites

Below are listed excavated or surveyed watermill sites dated to the ancient period.

| Site | Country | Date | Identification/Remains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouzaïa des Mines, near [50] | Algeria | Unspecified | Unspecified remains |

| Oued Bou Ardoun [50] | Algeria | Possibly 2nd to 3rd century AD | Unspecified remains |

| Oued Bou Ya'koub [50] | Algeria | Unspecified | Drop-tower mill |

| Oued Mellah [50] | Algeria | Possibly 4th century AD | Drop-tower mill |

| Ardleigh, Spring Valley Mill [51] | England | Unspecified | Possible Roman watermill site including millstones |

| Chesters[52] | England | Possibly 3rd century AD | Mill-race, mill-chamber, tail-race, millstones |

| Fullerton[53] | England | Unspecified | Two watermills |

| Haltwhistle Burn Head[54] | England | 225–70 AD | Entire establishment |

| Ickham I [55] | England | 150–280 AD | Mill-race, mill-building, fragments of millstones |

| Ickham II [56] | England | 3rd and 4th centuries AD | Mill-race, sluice-gate, mill-building, fragments of millstones |

| Nettleton[57] | England | 230 AD | Mill-race, sluice-gate, wheel-pit, tail-race |

| Wherwell[58] | England | Late 3rd or early 4th century AD | Mill-channel, mill-building (?), fragments of millstones |

| Willowford [59] | England | Late 2nd or 3rd century AD? [60] | Water-channels, sluices (?), fragments of millstones |

| Barbegal mill[61] | France | 2nd century AD [62] | Multiple mill complex with sixteen overshot wheels on two mill-races, fed by aqueduct |

| Fontvieille, Calade du Castellet [63] | France | 5th/6th century AD | Horizontal-wheeled mill |

| Gannes [64] | France | Presumably 4th or 5th century AD | Horizontal (?) water-wheel |

| La Bourse[65] | France | Late 5th century AD | Remains of waterwheel and curved trough. |

| La Crau[66] | France | 2nd century AD | Vertical-wheeled mill |

| La Garde (Var)[67] | France | Unspecified | Vertical-wheeled mill |

| Lattes[67] | France | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Le Cannet-des-Maures[68] | France | 5th century AD | Two horizontal-wheeled mills |

| Les Arcs (Var)[69] | France | 2nd/3rd century AD | Vertical-wheeled mill |

| Les Martres-de-Veyre I [70] | France | 1st century AD | Unspecified remains |

| Les Martres-de-Veyre II [70] | France | Late 2nd century AD [20] | Entire establishment; breastshot wheel [20] |

| Lyon-Vaise[71] | France | Late 1st century AD abandoned | Millstones, mill-chamber timbers |

| Paulhan I–III [72] | France | 40/50–early 3rd century AD | Three consecutive mills |

| Pézenas[73] | France | 2nd century AD | Horizontal-wheeled mill |

| Saint-Doulchard[74] | France | 1st century AD | Wooden paddles. |

| Taradeau[67] | France | Late 2nd–4th century AD | Horizontal-wheeled mill |

| Bobingen[75] | Germany | 117/138 AD | Posts, boards, mill-race |

| Dasing[76] | Germany | Merovingian | Timber posts and mill race, remains of wheel and paddles, millstones. |

| Inden[77] | Germany | End of 1st century BC | Millstones, wheel-shaft bearings, paddle fragments |

| Lösnich I [78] | Germany | 2nd/4th century AD? [20] | Mill-race, wheel-pit, fragment of a millstone |

| Lösnich II [78] | Germany | 2nd/4th century AD? [20] | Mill-race |

| Munich-Perlach [79] | Germany | End of 2nd century AD | Mill-chamber, mill-race, millstone fragments; possibly duplex drive |

| Athens, Agora I [80] | Greece | 5th and 6th centuries AD | Aqueduct, wheel-pit, mill-chamber, tail-race |

| Athens, Agora II [80] | Greece | 460/75 to c.580 AD | Entire establishment |

| Athens, Agora III [64] | Greece | Unspecified | Unspecified remains |

| El-Qabu [64] | Israel | Possibly Roman | Unspecified remains |

| En Shoqeq [64] | Israel | 2nd century AD | Masonry dam with mills |

| Farod I–III [64] | Israel | 5th or 6th century AD | Three drop-tower mills |

| Farod IV–V [64] | Israel | Unspecified | Two mills |

| Ma'agan Michael[64] | Israel | 3rd century AD? | Masonry dam, with eleven mills |

| Nahal Tanninim[81] | Israel | Early 4th/mid-7th century AD | Six vertical-wheeled mills with duplex drives and underdriven Pompeian millstones |

| Wadi Fejjas I–III [64] | Israel | Probably Roman | Three drop-tower mills |

| Wadi Serrar [64] | Israel | Probably Roman | Unspecified remains |

| Yarkon[64] | Israel | 2nd century AD | Unspecified remains |

| Oderzo[82] | Italy | 2nd century AD | Mill-race |

| Rome, Baths of Caracalla I [83] | Italy | Between 212/235 to mid-3rd century AD | Two vertical-wheeled mills |

| Rome, Baths of Caracalla II [84] | Italy | Mid-3rd century to 5th century AD | Two vertical-wheeled mills |

| Rome, Janiculum[85] | Italy | Early 3rd century AD [86] | Aqueducts, reservoirs, sluices, millstones |

| Saepinum[23] | Italy | Late 3rd or early 4th century AD [23] | Aqueduct, sluice-gates, wheel-pit, tail-race.[64] Recently identified as tanning mill.[23] |

| San Giovanni di Ruoti [87] | Italy | Early 1st century AD | Unspecified remains |

| Venafro[88] | Italy | Possibly early Empire | Undershot water wheel,[89] millstones |

| Gerasa[90] | Jordan | 6th century AD | Water-powered stone sawmill with two four-bladed saws; crank and connecting rod system without gear train |

| Jarash[91] | Jordan | 527-65 AD | Wheel-pit walls, bearing emplacements, supply cistern, partly sawn stone drums. |

| Wadi al-Hasa[64] | Jordan | Probably late Roman | At least nineteen possible drop-tower mills |

| Oued es Soueïr [50] | Morocco | Unspecified | Unspecified remains |

| Avenches [92] | Switzerland | 57/58–80 AD | Mill-race timbers |

| Rodersdorf, Klein Büel [93] | Switzerland | 1st century AD | Millstone, mill-race |

| Palmyra[64] | Syria | Possibly Roman | Unspecified remains |

| Chemtou[50] | Tunisia | Late 3rd or early 4th century AD | Triple helix turbine mill with horizontal wheels |

| Testour[50] | Tunisia | Late 3rd or early 4th century AD | Triple helix turbine mill with horizontal wheels |

| Colossae [94] | Turkey | Unspecified | Possible multiple-mill complex [95] |

| Kurşunlu Waterfall, near Perge[96] | Turkey | Unspecified | Unspecified remains |

| Lamus river[26] | Turkey | Apparently late antique | Seven horizontal-wheeled mills |

Millstones

The following list comprises stray finds of ancient millstones. Note that there is no way to distinguish millstones driven by water-power from those powered by animals turning a capstan. Most, however, are assumed to derive from watermills.[97]

| Site | Country | Date (or find context) | Remains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barton Court Farm [98] | England | 4th century AD well | Fragments of four millstones |

| Chedworth[98] | England | Roman villa | One lower stone, fragment of another |

| Chew Park [98] | England | Late 3rd or early 4th century AD | One complete upper stone, part of another |

| Dicket Mead[98] | England | Roman building | Fragments of millstones |

| Leeds[98] | England | Roman pottery dated to 1st and 2nd centuries AD | Fragment of millstone |

| Littlecote Roman Villa[98] | England | 2nd century AD timber building | Fragment of millstone |

| London[98] | England | 1st-2nd century AD | Several millstones |

| London[98] | England | Late 2nd century AD Roman ship | One unfinished millstone |

| Selsey[98] | England | Unspecified | Fragment of millstone |

| Vindolanda[99] | England | Possibly Roman | Four millstones |

| Wantage[99] | England | On display in museum | Two millstones |

| Woolaston[98] | England | c. 320 AD | Two upper millstones |

| La Chapelle-Taillefert[98] | France | Pottery and coins from 2nd century AD | Pair of millstones |

| Lyon[98] | France | On display in museum | Many unpublished millstones |

| Paris[99] | France | On display in museum | Six millstones |

| Aalen[98] | Germany | On display in museum | Five millstones |

| Cologne[99] | Germany | On display in museum | Three millstones |

| Dasing[100] | Germany | Unspecified | Fragments of millstones |

| Koblenz[98] | Germany | On display in museum | Several millstones |

| Mayen[98] | Germany | Quarry | Unfinished Roman millstones |

| Budapest[99] | Hungary | On display in museum | Six millstones |

| Beit She'an[98] | Israel | Late 4th or early 5th century AD | Upper millstone |

| Buqueiah [98] | Israel | Allegedly from ancient watermill | Upper millstone |

| Bologna[98] | Italy | On display in museum | Six millstones |

| Naples[98] | Italy | Probably Roman | Several millstones |

| Palatine, Rome[101] | Italy | 4th or 5th century AD | 47 millstones from at least five watermills |

| Apulum[98] | Romania | 2nd or 3rd century AD | Pair of millstones |

| Cluj-Napoca[98] | Romania | 2nd or 3rd century AD | Upper millstone |

| Micia[98] | Romania | 2nd or 3rd century AD | Pair of millstones |

| Caerwent[98] | Wales | Smithy | Millstones |

| Whitton [98] | Wales | Unspecified | Fragment of millstone |

Water wheels and other components

Although more rare than the massive millstones, finds of wooden and iron parts of the mill machinery can also point to the existence of ancient watermills.[102] Large stone mortars have been found at many mines; their deformations suggest automated crushing mills worked by water wheels.[103]

| Site | Country | Date (or find context) | Remains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Chesterford[98] | England | Early 5th century AD hoard | Iron spindle with three winged rynds |

| Silchester[98] | England | Mid-4th century AD hoard | Iron spindle |

| Saint-Doulchard[104] | France | 1/10 to c.50 AD | Paddles, mill-chamber posts |

| Conimbriga[99] | Portugal | On display in museum, allegedly 1st century AD | Mill-wheel |

| Hagendorn[105] | Switzerland | Late 2nd century AD | Three undershot wheels |

| Dolaucothi[8] | Wales | 1st and 2nd centuries AD | Stone anvil (Carreg Pumsaint) nearby |

References

- ^ Greene 2000, p. 39

- ^ a b Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 9

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 371

- ^ a b c Wikander 2000a, pp. 396f.; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 11; Wilson 2002, pp. 7f.

- ^ Wikander 2000a, pp. 373–378; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, pp. 12–15

- ^ a b Wikander 1985, p. 158; Wikander 2000b, p. 403; Wilson 2002, p. 16

- ^ a b c Wikander 2000b, p. 407

- ^ a b Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007

- ^ Wikander 2000b, pp. 406f.

- ^ Wikander 1985, pp. 151–154; Wikander 2000a, pp. 370–373; Wilson 2002, pp. 9–17; Brun 2006, pp. 7–9

- ^ Wikander 2000a, pp. 397–400

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 379

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 160; Wikander 2000a, p. 396

- ^ Wikander 2000a, pp. 373f.; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 12

- ^ a b Wikander 2000b, p. 402

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 375; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 13

- ^ a b Wikander 2000b, p. 406

- ^ Wikander 1985, pp. 154–162; Wilson 2002, p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g Wikander 2000a, p. 375

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 154

- ^ Wilson 1995, pp. 507f.; Wikander 2000a, p. 377; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 13

- ^ a b c d Brun & Leguilloux 2014, pp. 160–170; Wilson 2020, p. 171

- ^ Wilson 2001

- ^ Wikander 2000b, pp. 404f.

- ^ a b c Wilson 2001, p. 235

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 163, fn. 109; Wikander 2000a, p. 400

- ^ a b c Wikander 1985, p. 160

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 169, fn. 41

- ^ a b c Wikander 2000a, p. 398

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 160; Wikander 2000a, p. 398

- ^ a b Wikander 2000a, p. 400, fn. 123

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 171, fn. 82; Brun 2006, p. 105

- ^ a b Wikander 1985, p. 171, fn. 82

- ^ Wikander 2000b, p. 405

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 399, fn. 121

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 171, fn. 69

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 399

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 143–146

- ^ Spain 2008, p. 82

- ^ a b Wikander 1985, p. 158

- ^ a b Wikander 2000b, p. 403

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 396

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 161; Wikander 2000a, p. 397, fn. 104

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 170, fn. 45

- ^ a b Wikander 2000a, pp. 373f.

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 170, fn. 61; Wikander 2000a, p. 375

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 159

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 171, fn. 77; Wikander 2000a, pp. 384f.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilson 1995, pp. 507f.

- ^ Spain 1984, pp. 111–112

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 35–36

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 25–27

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 43–46

- ^ Spain 1984b, pp. 143–180

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 33–35

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 28–29

- ^ Spain 1984, pp. 115–116

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 36–37

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 397, fn. 106

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 14–25

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 11

- ^ Amouric et al. 2000

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Wikander 1985, pp. 154–162

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 29–31

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 21–22

- ^ a b c Brun 2006, p. 113

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 107, 113

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 113

- ^ a b Spain 2008, pp. 46–48

- ^ Brun & Borréani 1998, p. 315; Brun 2006, p. 112

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 113, 116

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 107, 116

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 51

- ^ Wikander 2014, p. 207

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 40–41

- ^ Geilenbrügge 2010, p. 4; Geilenbrügge & Schürmann 2010; Images: 1 and 2

- ^ a b Spain 2008, pp. 61–63

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 41f.; Wikander 2014, p. 207

- ^ a b Spain 2008, pp. 55–59

- ^ Ad, Saʿid & Frankel 2005; Spain 2008, pp. 59–61

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 42f.

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 22–24

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 51–55

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 37–40

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 393

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 374

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 64–67

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 385

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 16; Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 149–151

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 24–25

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 31–32

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 111f.

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 59

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 394, fn. 95

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 105, 107

- ^ Wikander 2000a, p. 372

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Wikander 1985, pp. 163–165

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson 2002, pp. 10

- ^ Czysz 1994, p. 152

- ^ Brun 2006, pp. 107, 110

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 165

- ^ Burnham 1997, pp. 332–336

- ^ Champagne, Ferdière & Rialland 1997; Brun 2006, p. 112

- ^ Spain 2008, pp. 49–50

Notes

- ^ Character as watermill disputed (Wilson 1995, p. 375)

Sources

Watermill lists which summarize the rapidly developing state of research are provided by Wikander 1985 and Brun 2006, with additions by Wilson 1995 and 2002. Spain 2008 undertakes a technical analysis of around thirty known ancient mill sites.

- Ad, Uzi; Saʿid, ʿAbd al-Salam; Frankel, Rafael (2005), "Water-mills with Pompeian-type Millstones at Nahal Tanninim", Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 156–171

- Amouric, Henri; Thernot, Robert; Vacca-Goutouli, Mireille; Bruneton, Hélène (2000), "Un moulin à turbine de la fin de l'Antiquité. La Calade du Castellet (Fontvieille)", in Leveau, Philippe; Saquet, J. P. (eds.), Milieu et sociétés dans la Vallée des Baux. Études présentées au colloque de Mouriès, Revue Archéologique de Narbonnaise (Supplement), vol. 31, Montpellier: Association de la Revue Archéologique de Narbonnaise, pp. 261–274, ISBN 978-2-84269-369-5

- Brun, Jean-Pierre (2006), "L'energie hydraulique durant l'Empire romain: quel impact sur l'economie agricole?", in Lo Cascio, Elio (ed.), Innovazione tecnica e progresso economico nel mondo romano: atti degli Incontri capresi di storia dell'economia antica (Capri 13-16 Aprile 2003), Bari: Edipuglia, pp. 101–130, ISBN 978-88-7228-405-6

- Brun, Jean-Pierre; Borréani, Marc (1998), "Deux moulins hydrauliques du Haut-Empire romain en Narbonnaise: Villae des Mesclans à La Crau et de Saint-Pierre/Les Laurons aux Arcs (Var)", Gallia, vol. 55, pp. 279–326

- Brun, Jean-Pierre; Leguilloux, Martine Leguilloux (2014), "Les installations artisanales romaines de Saepinum. Tannerie et moulin hydraulique", Collection du Centre Jean Bérard 43, Archéologie de l’artisanat antique 7, Naples: Centre Jean Bérard, ISSN 1590-3869

- Burnham, Barry C. (1997), "Roman Mining at Dolaucothi: The Implications of the 1991–3 Excavations near the Carreg Pumsaint", Britannia, vol. 28, pp. 325–336, doi:10.2307/526771

- Champagne, Frédéric; Ferdière, Alain; Rialland, Yannick (1997), "Re-découverte d'un moulin à eau augustéen sur l'Yèvre (Cher)", Revue archéologique du Centre de la France, vol. 36, pp. 157–160

- Czysz, Wolfgang (1994), "Eine bajuwarische Wassermühle im Paartal bei Dasing", Antike Welt, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 152–154

- Donners, K.; Waelkens, M.; Deckers, J. (2002), "Water Mills in the Area of Sagalassos: A Disappearing Ancient Technology", Anatolian Studies, vol. 52, pp. 1–17, doi:10.2307/3643076, JSTOR 3643076

- Geilenbrügge, Udo (2010), Älteste Wassermühle Mitteleuropas entdeckt (PDF), Archäologie in Deutschland, vol. 2010/1, Stuttgart: Theiss, p. 4, ISSN 0176-8522

- Geilenbrügge, Udo; Schürmann, Wilhelm (2010), "Die älteste Wassermühle Mitteleuropas im Indetal bei Altdorf?", in Kunow, Jürgen (ed.), Archäologie im Rheinland 2009, Archäologie im Rheinland, Stuttgart: Theiss, pp. 62–64, ISBN 978-3-8062-2383-5

- Greene, Kevin (2000), "Technological Innovation and Economic Progress in the Ancient World: M.I. Finley Re-Considered", The Economic History Review, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 29–59, doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00151, hdl:10.1111/1468-0289.00151

- Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 20, pp. 138–163

- Spain, Robert (1984), "Romano-British Watermills", Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. 100, Kent Archaeological Society, pp. 101–128

- Spain, Robert (1984b), "The Second-Century Romano-British watermill at Ickham, Kent", History of Technology, vol. 9, pp. 143–180

- Spain, Robert (2008), The Power and Performance of Roman Water-mills. Hydro-mechanical Analysis of Vertical-wheeled Water-mills, British Archaeological Reports. International Series, vol. 1786, Oxford: Archaeopress, ISBN 978-1-4073-0217-1

- Wikander, Örjan (1985), "Archaeological Evidence for Early Water-Mills. An Interim Report", History of Technology, vol. 10, pp. 151–179

- Wikander, Örjan (2000a), "The Water-Mill", in Wikander, Örjan (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, vol. 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 371–400, ISBN 90-04-11123-9

- Wikander, Örjan (2000b), "Industrial Applications of Water-Power", in Wikander, Örjan (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, vol. 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 401–410, ISBN 90-04-11123-9

- Wikander, Örjan (2014), "Early Water-mills East of the Rhine", in Karlsson, Lars; Carlsson, Susanne; Kullberg, Jesper (eds.), ΛΑΒΡΥΣ. Studies presented to Pontus Hellström, Boreas. Uppsala Studies in Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Civilizations, vol. 35, Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet, pp. 205–219, ISBN 978-91-554-8831-4

- Wilson, Andrew (1995), "Water-Power in North Africa and the Development of the Horizontal Water-Wheel", Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 8, pp. 499–510

- Wilson, Andrew (2001), "Water-Mills at Amida: Ammianus Marcellinus 18.8.11" (PDF), The Classical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 231–236, doi:10.1093/cq/51.1.231

- Wilson, Andrew (2002), "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 92, pp. 1–32, doi:10.2307/3184857, JSTOR 3184857

- Wilson, Andrew (2020), "Roman Water-Power. Chronological Trends and Geographical Spread", in Erdkamp, Paul; Verboven, Koenraad; Zuiderhoek, Arjan (eds.), Capital, Investment, and Innovation in the Roman World, Oxford University Press, pp. 147–194, ISBN 978-0-19-884184-5

Further reading

- Kessener, Paul (2010), "Stone Sawing Machines of Roman and Early Byzantine Times in the Anatolian Mediterranean", Adalya, vol. 13, pp. 283–303, ISSN 1301-2746

External links

![]() Media related to Roman mills at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Roman mills at Wikimedia Commons

- Traianus – Technical investigation of Roman public works

- The Oxford Roman Economy Project: The uptake of mechanical technology in the ancient world: the water-mill – Quantitative data on watermills up to 700 AD