FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

Robert Livingston | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Gilbert Stuart | |

| 7th United States Minister to France | |

| In office December 6, 1801 – November 18, 1804 | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney |

| Succeeded by | John Armstrong |

| 1st United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office October 20, 1781 – June 4, 1783 | |

| Appointed by | Congress of the Confederation |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | John Jay |

| 1st Chancellor of New York | |

| In office July 30, 1777 – June 30, 1801 | |

| Appointed by | Governor William Tryon |

| Governor | George Clinton John Jay |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | John Lansing |

| Recorder of New York City | |

| In office October 13, 1773 – 1774 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jones |

| Succeeded by | John Watts Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 27, 1746 New York City, New York, British America |

| Died | February 26, 1813 (aged 66) Clermont, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse |

Mary Stevens (m. 1770) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Robert Livingston (father) Edward Livingston (brother) Robert Livingston (grandfather) |

| Education | Columbia College (BA) |

| Signature | |

Robert Robert[a] Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor" after the high New York state legal office he held for 25 years. He was a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, along with Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Roger Sherman, but was recalled by the state of New York before he could sign the document. Livingston administered the oath of office to George Washington when he assumed the presidency April 30, 1789. Livingston was also elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1801.[1]

Early life

Livingston was the eldest son of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (née Beekman) Livingston, uniting two wealthy Hudson River Valley families. He had three brothers and five sisters, all of whom wed and made their homes on the Hudson River near the family seat at Clermont Manor. Among his siblings were his younger brother, Edward Livingston (1764-1836), who also served as U.S. Minister to France and Secretary of State, his sister Gertrude Livingston (1757–1833), who married Governor Morgan Lewis (1754–1844), sister Janet Livingston (d. 1824), who married Richard Montgomery (1738–1775), sister Alida Livingston (1761–1822), who married John Armstrong, Jr. (1758–1843) (who succeeded him as U.S. Minister to France), and sister Joanna Livingston (1759–1827), who married Peter R. Livingston (1766–1847).[2]

His paternal grandparents were Robert Livingston (1688–1775) of Clermont and Margaret Howarden (1693–1758). His great-grandparents were Robert Livingston the Elder (1654–1728) and Alida (née Schuyler) Van Rensselaer Livingston, daughter of Philip Pieterse Schuyler (1628–1683). His grand-uncle was Philip Livingston (1686–1749), the 2nd Lord of Livingston Manor.[3] Livingston, a member of a large and prominent family, was known for continually quarreling with his relatives.[4]

Livingston graduated from King's College[b] in June 1765 and was admitted to the bar in 1773.[5][6]

Career

Recorder of New York City

In October 1773, Livingston was appointed recorder of New York City but soon thereafter identified himself with the anti-colonial Whig Party and was replaced a few months later by John Watts, Jr.

Chancellor of New York

On July 30, 1777, Livingston became the first chancellor of New York, which was then the highest judicial officer in the state. Concurrently, he served from 1781 to 1783 as the first United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs under the Articles of Confederation. Livingston administered the presidential oath of office to George Washington at his first inauguration on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City, which was then the nation's capital.

In 1789, Livingston joined the Jeffersonian Republicans (later known as the Democratic-Republicans), forming an uneasy alliance with his previous rival George Clinton and Aaron Burr, then a political newcomer.[7] Livingston opposed the Jay Treaty and other initiatives of the Federalist Party, founded and led by his former colleagues Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. He ran for governor of New York as a Democratic-Republican, unsuccessfully challenging incumbent governor John Jay in the 1798 election.[8]

After serving as chancellor for almost 24 years, Livingston left office on June 30, 1801. During that period, he became nationally known by his title alone as "The Chancellor", and even after leaving office, he was respectfully addressed as Chancellor Livingston for the remainder of his life.

Declaration of Independence

On June 11, 1776, Livingston was appointed to a committee of the Second Continental Congress, known as the Committee of Five, which was given the task of drafting the Declaration of Independence. After establishing a general outline for the document, the committee decided that Jefferson would write the first draft.[9] The committee reviewed Jefferson's draft, making extensive changes,[10] before presenting Jefferson's revised draft to Congress on June 28, 1776. Before he could sign the final version of the Declaration, Livingston was recalled by his state. However, he sent his cousin, Philip Livingston, to sign the document in his place. Another cousin, William Livingston, would go on to sign the United States Constitution.

U.S. Minister to France

Following Thomas Jefferson's election as President of the United States, once Jefferson became president on March 4, 1801, he appointed Livingston U.S. minister to France. Serving from 1801 to 1804, Livingston negotiated the Louisiana Purchase. After the signing of the Louisiana Purchase agreement in 1803, Livingston made this memorable statement:

We have lived long but this is the noblest work of our whole lives ... The United States takes rank this day among the first powers of the world.[11]

During his time as U.S. minister to France, Livingston met Robert Fulton, with whom he developed the first viable steamboat, the North River Steamboat, whose home port was at the Livingston family home of Clermont Manor in the town of Clermont, New York. On her maiden voyage, she left New York City with him as a passenger, stopped briefly at Clermont Manor, and continued to Albany up the Hudson River, completing in just under 60 hours a journey that had previously taken nearly a week by sloop sailboat. In 1811, Fulton and Livingston became members of the Erie Canal Commission.

Freemasonry and the Society of Cincinnati

Livingston was a Freemason, and in 1784, he was appointed the first Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of New York, retaining this title until 1801. The Grand Lodge's library in Manhattan bears his name. The Bible Livingston used to administer the oath of office to President Washington is owned by St. John's Lodge No. 1 and is still used today when the Grand Master is sworn in, and, by request, when a President of the United States is sworn in.

On July 4, 1786, he was part of the second group elected as honorary members of the New York Society of the Cincinnati, along with Chief Justice Richard Morris, Judge James Duane, Continental Congressman William Duer, and Justice John Sloss Hobart.[12]

Personal life

On September 9, 1770, Livingston married Mary Stevens (1751–1814), the daughter of Continental Congressman John Stevens and sister of the inventor John Stevens III.[13] Following their marriage, he built a home south of Clermont, called Belvedere, which was burned to the ground along with Clermont in 1777 by the British Army under General John Burgoyne. In 1794, he built a new home called New Clermont, which was subsequently renamed Arryl House, a phonetic spelling of his initials "RRL", which was deemed "the most commodious home in America" and contained a library of four thousand volumes.[14][15] Together, Robert and Mary were the parents of:[2]

- Elizabeth Stevens Livingston (1780–1829), who married Lt. Governor Edward Philip Livingston (1779–1843), the grandson of Philip Livingston, on November 20, 1799.

- Margaret Maria Livingston (1783–1818), who married Robert L. Livingston (1775–1843), the son of Walter Livingston and Cornelia Schuyler, on July 10, 1799.

Death

Livingston died a natural death aged 75 on February 26, 1813, and was buried in the Clermont Livingston vault at St. Paul's Church in Tivoli, New York.

Livingston family

Through his eldest daughter Elizabeth he was the grandfather of four:

- Margaret Livingston (1808–1874), who married David Augustus Clarkson (1793–1850)[16]

- Elizabeth Livingston (1813–1896), who married Edward Hunter Ludlow (1810–1884)[17]

- Clermont Livingston (1817–1895), who married Cornelia Livingston (1824–1851)[13]

- Robert Edward Livingston (1820–1889), who married Susan Maria Clarkson de Peyster (1823–1910)[18][19]

Legacy and honors

- Livingston County, Kentucky,[20] and Livingston County, New York, are named for him.

- A statue of Livingston by Erastus Dow Palmer was commissioned by the state of New York and placed in the National Statuary Hall collection of the U.S. Capitol building, according to the tradition of each state selecting two individuals from the state to be so honored.

- Livingston is included on the Jefferson Memorial pediment sculpture by Adolph Alexander Weinman, which honors the Committee of Five.

- The Robert Livingston high-rise building at 85 Livingston St. in Brooklyn is named for him.

- The Chancellor Robert R. Livingston Masonic Library of the Grand Lodge of the State of New York is named in his honor, and is house at Masonic Hall in New York City.[21]

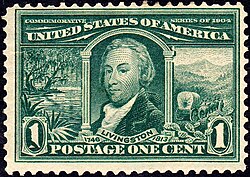

Robert Livingston Issue of 1904 |

Map of Louisiana Purchase Issue of 1904 |

|

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ At the time, the Livingstons used their father's first names as middle names to distinguish the numerous members of the family, as a kind of patronymic. Since Robert and his father had the same name, he never spelled out the middle name but always used only the initial.

- ^ King's College was renamed Columbia College of Columbia University following the American Revolution in 1784.

References

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ a b Livingston, Edwin Brockholst (1910). The Livingstons of Livingston Manor: Being the History of that Branch of the Scottish House of Callendar which Settled in the English Province of New York During the Reign of Charles the Second; and Also Including an Account of Robert Livingston of Albany, "The Nephew," a Settler in the Same Province and His Principal Descendants. Knickerbocker Press. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ "Livingston, Robert R. (1718–1775), [The Petition of Michael Theyser of the City of New York, Innkeeper]". www.gilderlehrman.org. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ Dangerfield, George (1960-11-16). "Chancellor Robert R. Livingston of New York". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ Brandt, Clare (March 1987). "Robert R. Livingston, Jr.: The Reluctant Revolutionary" (PDF). The Hudson Valley Regional Review. Vol. 4, no. 1. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-11. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ Johnson, Rossiter; Brown, John Howard, eds. (1906). The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. VI. Boston: American Biographical Society. Retrieved 2022-05-09 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Robert R. Livingston, Encyclopedia of World Biography.

- ^ Schechter, Stephen L.; Tripp, Wendell Edward (1990). World of the Founders: New York Communities in the Federal Period. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780945660026.

- ^ Boyd, Julian Parks; Gawalt, Gerard W. (1999). The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text. Library of Congress. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8444-0980-1.

- ^ Boyd, Julian P., ed. (4 July 1995). "Jefferson's 'original Rough draught' of the Declaration of Independence". Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02.

- ^ The Louisiana State Capitol Building Archived December 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schuyler, John (1886). Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati : formed by the officers of the American Army of the Revolution, 1783, with extracts, from the proceedings of its general meetings and from the transactions of the New York State Society. New York: Printed for the Society by D. Taylor. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ a b The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. XI. New York City: New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. 1880. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ Yasinsac, Rob. "Arryl House". www.hudsonvalleyruins.org. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ "Clermont State Historic Site: Imagining Arryl House: Piecing Together an Architectural Masterpiece". October 25, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ Jay, Elizabeth Clarkson (April 1881). "The Descendants of James Alexander". The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. XII (2): 61. Retrieved 2022-05-09 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Death of Edward H. Ludlow". The New York Times. 28 November 1884. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-05-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "G. Livingston Dies; Long an Architect; Practitioner Here for 50 Years Included Hayden Planetarium, Oregon Capitol in His Work". The New York Times. June 4, 1951. p. 26. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Mrs. Susan de Peyster Livingston". The New York Times. February 11, 1910. p. 11. Retrieved 2022-05-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Collins, Lewis (1877). History of Kentucky. Library Reprints, Incorporated. p. 478. ISBN 9780722249208.

- ^ "Chancellor Robert R Livingston Masonic Library – Collecting, Studying, and Preserving Masonic Heritage". Retrieved 2024-02-10.

Further reading

- Alexander, D. S. "Robert R. Livingston, The Author of the Louisiana Purchase." Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association 6 (1906): 100–114.

- Bonham, Jr., Milledge L. "Robert R. Livingston". in Samuel Flagg Bemis, ed. The American Secretaries of State and their diplomacy V.1 (1928) pp. 115–192.

- Brandt, Clare. An American Aristocracy: The Livingstons (Doubleday Books, 1986).

- Brecher. Frank W. Negotiating the Louisiana Purchase: Robert Livingston's Mission to France, 1801–1804 (McFarland, 2006)

- Dangerfield, George. Chancellor Robert R. Livingston of New York, 1746–1813 (1960)

- online review; also another review

- De Peyster, Frederic. "A Biographical Sketch of Robert R. Livingston" (NY Historical Society, October 3, 1876) online

Primary sources

- Livingston, Robert R. The Original Letters of Robert R, Livingston, 1801–1803 ed. by Edward A. Parsons (1953).