FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

Piccadilly Theatre in November 2023 | |

| |

| Address | Denman Street London, W1 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°30′38″N 0°08′03″W / 51.510611°N 0.134194°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | ATG Entertainment |

| Type | West End theatre |

| Capacity | 1,232 on 3 levels |

| Production | Moulin Rouge! |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 27 April 1928 |

| Architect | Bertie Crewe and Edward A. Stone |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Piccadilly Theatre is a West End theatre located at the junction of Denman Street and Sherwood Street, near Piccadilly Circus, in the City of Westminster, London. It opened in 1928.

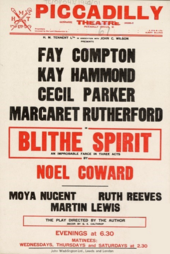

In its early years the theatre presented a wide range of productions, and was briefly a cinema. During the Second World War it presented productions ranging from the premiere of Noël Coward's Blithe Spirit to John Gielgud's lavish production of Macbeth. Later productions in the 1940s and 1950s included Cole Porter's Panama Hattie (1943), Coward's revue Sigh No More (1945) and Peter Ustinov's Romanoff and Juliet (1956).

In 1964 the Piccadilly presented the British premiere of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but by this time musicals had begun to outnumber non-musical plays at this theatre, with revivals of Oliver! and Man of La Mancha, and later productions including Gypsy (1973), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1986), A Little Night Music (1989), The Rocky Horror Show (1990), Guys and Dolls (2005), Grease (2007), Jersey Boys (2014) and Moulin Rouge! (2022). The house has had more success with revivals than with premieres of musicals, and has been the scene of several new shows that closed shortly after opening.

The theatre has been home to many productions of the classics, with plays by Shakespeare, Marlowe, Molière, Shaw and more modern authors including Samuel Beckett, Arthur Miller, Alan Bennett, Tom Stoppard and Willy Russell. Among the actors appearing at the Piccadilly have been Henry Fonda, Frankie Howerd, Marcel Marceau, Ian McKellen, Simon Russell Beale, Paul Scofield and Timothy West; actresses have included Gladys Cooper, Edith Evans, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, Joyce Grenfell, Angela Lansbury, Evelyn Laye, Prunella Scales and Julie Walters.

History

Early years

The impresario Edward Laurillard acquired a site behind Piccadilly Circus occupied by derelict stables, and built a theatre there. It was designed by Bertie Crewe and Edward A. Stone. A simple façade concealed an elaborate Art Deco interior designed by Marc-Henri Levy and Gaston Laverdet, with a 1,232-seat auditorium decorated in shades of pink;[1] it was claimed that if all the bricks used in the building were laid in a straight line, they would stretch from London to Paris.[2]

The theatre opened on 27 April 1928. The opening production, Blue Eyes, a musical with words by Guy Bolton and Graham John and music by Jerome Kern, starred Evelyn Laye; it ran at the Piccadilly and then at Daly's Theatre for a total of 276 performances.[1]

The Piccadilly was briefly taken over by Warner Brothers and operated as a cinema using the Vitaphone system; among the films shown was The Singing Fool with Al Jolson. The theatre reopened in November 1929, with a production of The Student Prince, which was followed in January 1931 by Folly to be Wise, a revue by Dion Titheradge and Vivian Ellis, starring Cicely Courtneidge with Nelson Keys and Mary Eaton; it ran for 257 performances.[1][3]

The next production (September 1933) was James Bridie's A Sleeping Clergyman, considered by some to be Bridie's best play, according to the theatre historians Mander and Mitchenson; Ernest Thesiger and Robert Donat both scored great successes in the piece.[1] It had 230 performances and was followed by Counsellor at Law by Elmer Rice (April 1934, 126 performances) and Queer Cargo by Noel Langley (August 1934, 109 performances). After that there was, in Mander and Mitchenson's words "a bad patch in this theatre's history", during which the Windmill Theatre, known for its nude tableaux vivants, extended its activities to the Piccadilly.[1]

In December 1937 the Piccadilly reopened after redecoration and the addition of new bars and stalls entrances, with Choose your Time, a novel form of entertainment devised by Firth Shephard. It consisted of a miscellaneous programme of newsreels, a live "swingphonic" orchestra, individual turns, Donald Duck films, and, as what The Stage called its pièce de résistance, a one-act stage comedy called Talk of the Devil by Anthony Pelissier, featuring Yvonne Arnaud, John Mills and Naunton Wayne.[4] After this the theatre became a receiving house for transfers of long runs at reduced prices.[1]

1940s

From the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 the Piccadilly was closed until Noël Coward's Blithe Spirit premiered there in July 1941, starring Fay Compton, Kay Hammond, Cecil Parker and Margaret Rutherford.[5] The play ran at the Piccadilly until March 1942, before transferring to the smaller St James's and later the Duchess Theatres to complete its run of 1,997 performances.[5] Other wartime productions at the Piccadilly included Macbeth in 1942 starring John Gielgud and Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies in a lavish production designed by Michael Ayrton and John Minton, with music by William Walton.[6]

After that came two musicals, both in 1943; the first was Oscar Hammerstein II and Sigmund Romberg's Sunny River, presented by Emile Littler, starring Laye, Dennis Noble, Edith Day and Bertram Wallis.[7] The critic James Agate wrote that the plot did not hold water but he nonetheless rated it the best musical show since Coward's 1929 Bitter Sweet, for numerous reasons, chief of which were that "the plot is not more nonsensical than any other ... there is a complete absence of jazz or swing ... the songs are sung, not crooned, and the singers have the voices to sing them".[8] Despite this, the show did not have a long run, closing after 86 performances.[9]

The second musical was Cole Porter's Panama Hattie, starring Bebe Daniels, Max Wall and Claude Hulbert.[10] It ran for 308 performances.[11] Towards the end of the war the Piccadilly was damaged by German bombing, and remained closed for some months. It reopened with Agatha Christie's thriller Appointment with Death in March 1945. Mary Clare led the cast, which also included Joan Hickson and Carla Lehmann.[12]

Later productions included Coward's revue Sigh No More (1945), starring Cyril Ritchard, Madge Elliott, Joyce Grenfell and Graham Payn. Despite several songs that later became well known, such as "I Wonder What Happened to Him", "That Is the End of the News" and "Matelot", it fell far short of the success of Blithe Spirit, running for 213 performances.[13] A Man About the House (1946), a crime story, starred Flora Robson and Basil Sydney.[14] Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra with Edith Evans and Godfrey Tearle (1946) divided critical opinion. Tearle received uniformly excellent notices, but Evans (aetat 59) convinced some critics more than others.[15]

John van Druten's The Voice of the Turtle (1947) was described by The Observer as "a little New York piece of the Boy-Meets-Two-Girls order", and closed after 62 performances.[16] Mander and Mitchenson describe the next six years as a period of short runs and transfers.[1]

1950s

A Question of Fact by Wynyard Browne (December 1953) had a cast headed by Pamela Brown, Paul Scofield and Gladys Cooper, and ran for 332 performances.[17] A spell of unsuccessful presentations followed until December 1955, when A Girl Called Jo – a musical adaptation of Little Women – opened. It starred Joan Heal and Denis Quilley, and ran until the following May.[1][18] It was followed by Peter Ustinov's romantic and satirical comedy Romanoff and Juliet, which ran from May 1956 for 379 performances.[19]

Four fairly successful runs followed in the next three years. Rodney Ackland's courtroom drama A Dead Secret starred Scofield as a (probable) poisoner, and ran from July 1957 for 212 performances.[20] Benn Levy's comedy The Rape of the Belt was a modern treatment of a classical legend, starring Hammond as Hippolyta, John Clements as Heracles, Constance Cummings as Antiope, Richard Attenborough as Theseus and Nicholas Hannen as Zeus; it ran for 298 performances from December 1957.[21] André Roussin's comedy Hook, Line and Sinker, adapted by and starring Robert Morley, co-starred Joan Plowright and Bernard Cribbins;[22] it opened in November 1958 and ran until 28 March 1959.[23] The Marriage-go-Round, a comedy by Leslie Stevens starring Hammond, Clements and Angela Browne opened in November 1959 and ran for 210 performances.[24]

1960s

For the Piccadilly the decade started with two conspicuous failures. The Golden Touch, a musical depicting a colony of beatniks on a Greek island, opened and closed in May 1960, and Bachelor Flat, described by The Stage as "yet another American play based on the well-worn theme of the teenage girl, half-baby, half-sophisticate"[25] ran for less than a week in June 1960.[9] A revival of Shaw's Candida from the Oxford Playhouse starred Michael Denison and Dulcie Gray and ran for 160 performances at the Piccadilly and then at Wyndham's Theatre.[26]

After a season of foreign dance companies, the Dublin Festival Company appeared in a revival of The Playboy of the Western World starring Donal Donnelly as Christy and Siobhan McKenna as Pegeen; it ran for 110 performances.[27] That was followed in November 1960 by Lilian Hellman's drama, Toys in the Attic, with Wendy Hiller, Diana Wynyard, Coral Browne and Ian Bannen.[28] In December it emerged that the impresarios Bernard Delfont and Donald Albery were in rival bids to take over the theatre; Albery won, and installed his son Ian as general manager.[9] The Alberys had the theatre refurbished, and installed back-stage improvements.[9]

The comedy The Amorous Prawn transferred from the Saville in January 1961, with a cast headed by Laye.[29] It completed a total run of 911 performances in February 1962.[30] For the rest of 1962 the Piccadilly had a series of short runs – some limited seasons and others unsuccessful productions. The former included a Festival of French Theatre and two seasons by Marcel Marceau.[9] On 8 October the West End production of the musical Fiorello! opened. The show, about the political reformer Fiorello La Guardia, had been a big success on Broadway, running for 795 performances,[31] but reviewers felt that the London cast failed to put the show across with suitable Broadway flair and vigour, not helped by interpolations intended to explain New York politics to British audiences.[32] It closed on 24 November after 56 performances, and Marceau returned for his second limited season (19 performances).[33] A stage version of the popular television comedy series The Rag Trade, starring Peter Jones and Miriam Karlin, did not match the appeal of the small-screen original, and ran for 85 performances from 19 December 1962 to 23 February 1963.[34]

Most of 1963 was occupied by what Mander and Mitchenson describe as "seasons of ballet, an Italian musical and some French plays".[9] In September Ronald Millar's adaptation of C. P. Snow's novel The Masters, transferred from the Savoy, and continued until early in 1964. The next big success at the Piccadilly was Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which opened in February 1964. For the first weeks of the run the leading roles were played by Uta Hagen and Arthur Hill, who had created them on Broadway; they were succeeded in May by Constance Cummings and Ray McAnally.[35] The production transferred to the Globe in July to make way for a musical, Instant Marriage, starring Joan Sims. Despite being described in The Times as "wretchedly written ... ill-constructed", it ran for 366 performances from 1 August 1964.[36]

1965 was mainly a year of short runs, including seasons of folk dancers and further ballets.[9] Neil Simon's comedy Barefoot in the Park, starring Mildred Natwick, Daniel Massey and Marlo Thomas, ran for 243 performances between November 1965 and June 1966.[37] A revival of Lionel Bart's musical Oliver! opened in April 1967, starring Barry Humphries and Marti Webb, running for 331 performances.[38] The next musical, Man of La Mancha, with Keith Michell, opened in April 1968, and was followed over the Christmas season by a musical adaptation of Daisy Ashford's novel, The Young Visiters with Alfred Marks as Mr Salteena and Jan Waters as Ethel.[39] Man of La Mancha returned in the new year, this time with Richard Kiley (who had created the title role on Broadway) in the lead.[9]

1970s

The Prospect Theatre Company presented a transfer from the Edinburgh Festival of Shakespeare's Richard II and Marlowe's Edward II in a limited season from 20 January to 21 March 1970. Ian McKellen played the title roles, and the company included Timothy West, James Laurenson, Robert Eddison and Peggy Thorpe-Bates.[40] A thriller, Who Killed Santa Claus?, starring Honor Blackman, ran from April to September 1970. The following month Vivat! Vivat Regina! by Robert Bolt transferred from the Chichester Festival with Eileen Atkins as Elizabeth I, Sarah Miles as Mary Queen of Scots and Richard Pearson as Cecil; The Guardian called it the best historical play in London for a decade; it ran for 442 performances.[41] In November 1971, again from Chichester, came Jean Anouilh's Dear Antoine, with Isabel Jeans in the role of Carlotta (created at Chichester by Edith Evans) and Clements in the title role.[42] Despite enthusiastic notices the production closed after 45 performances.[43] In February 1972 there was a further transfer from Chichester, a revival of Robert E. Sherwood's 1931 romantic comedy Reunion in Vienna, starring Nigel Patrick and Margaret Leighton. The play – though not the actors – received lukewarm notices and the production closed after 44 performances.[44]

After that was a transfer from the Prince of Wales Theatre of The Threepenny Opera, with Joe Melia as Macheath,[45] and in July 1972 there was a new British musical "for kids of all ages", Pull Both Ends.[46] In November another musical, I and Albert, was presented but is described by Mander and Mitchenson as an expensive failure, closing after 120 performances.[47] In May 1973 the Piccadilly had a solid success with the musical Gypsy starring Angela Lansbury, who was later succeeded by Dolores Gray. It ran for 300 performances.[48] In March 1974 Tennessee Williams's popular melodrama A Streetcar Named Desire was revived with Claire Bloom, Joss Ackland and Martin Shaw, and ran for 243 performances.[49]

Productions at the Piccadilly in the rest of the 1970s included Alun Owen's Male of the Species, a set of three short plays (24 October 1974);[50] and a thriller by Francis Durbridge, The Gentle Hook (142 performances from December 1974;[51] Neil Simon's The Sunshine Boys opened in May 1975 starring Alfred Marks and Jimmy Jewel; it ran for 77 performances, falling far short of the original Broadway run of 538.[52] Henry Fonda made his British stage debut at the Piccadilly in Clarence Darrow in July 1975; it ran for 47 performances,[53] and was followed by two musicals, Kwa Zulu, which ran for 166 performances from September,[54] succeeded in March 1976 by a revival of Bolton and Kern's 1915 musical Very Good Eddie, which had a run of 411 performances.[55]

The Royal Shakespeare Company occupied the Piccadilly for transfers of two of its productions: the 1791 comedy Wild Oats in April 1977 (324 performances),[56] and Privates on Parade in February 1978 (208 performances).[57] Vieux Carré by Tennessee Williams opened in August 1978; it divided critical opinion, which ranged from The Observer's view that it was on the same level as A Streetcar Named Desire to The Guardian's that it was "a vortex of silliness ... dire bathos".[58] It had a run of 118 performances, which was 112 more than it had achieved when premiered in New York.[59]

Over the 1978–79 Christmas season the theatre presented matinées of Toad of Toad Hall and evening performances of Barry Humphries's one-man show A Night with Dame Edna.[60] An evening based on French songs, The French Have a Song for It, transferred from the intimate King's Head Theatre and ran briefly in May 1979,[61] followed later in the month by Can You Hear Me at the Back?, a drama by Brian Clark; it ran for 300 performances.[62]

1980s

Educating Rita, starring Julie Walters, opened at the Piccadilly in August 1980 and ran until September 1982; Shirin Taylor took over the title role in April 1981.[63] In January 1983 what was described as "a unique £1.5 million theatre experiment, backed entirely by continental money" was announced for the Piccadilly.[64] In an attempt to convert Londoners to a new style of entertainment, the auditorium was converted to resemble a nightclub for the opening of a new musical called i in March.[64] The show was scrapped before the opening night, with heavy losses for its backers.[65] A replacement show, given the title Y, opened in June,[66] and ran until July 1984.[67]

In September 1984 an American musical, Pump Boys and Dinettes opened, running at the Piccadilly until June 1985, when it continued its run at another theatre.[68] Mutiny – a musical telling of the mutiny on the Bounty, by and starring David Essex – opened on 18 July 1985 and ran until October the following year.[69] In November 1986 Frankie Howerd starred in a revival of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,[70] which ran until 27 December.[71] In February and March 1987 Fascinating Aida played a limited season.[72] Lady Day, a musical about Billie Holiday, then ran briefly,[73] followed by a three-month run of Tom Stoppard's comedy Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, from June to September.[74] "Blues in the Night", described by The Times as a "hit black blues show", opened on 28 September and ran until 23 July 1988.[75] It was followed in August by Stop! In the Name of Love, celebrating female singing groups of the 1960s; this ran until November.[76]

The theatre was closed from then until March 1989, when a musical adaptation of the 1927 science fiction film Metropolis opened; one of the West End's most expensive shows up to that time, it closed in September, making a loss of £2.5 million.[77] The Piccadilly's last production of the 1980s was a revival of Stephen Sondheim's musical A Little Night Music, from the Chichester Festival, starring Dorothy Tutin, Peter McEnery and Susan Hampshire. It opened on 10 October and ran until 17 February 1990.[78]

1990s

In one of its many revivals The Rocky Horror Show opened at the Piccadilly in July 1990 and ran until June 1991.[79] Over the Christmas season Cilla Black starred in a pantomime, Jack and the Beanstalk.[80] In March 1991 a musical, Moby Dick, described as "Sixth-form girls perform Herman Meville's novel in their school swimming-pool",[81] opened to poor notices, and closed in early July.[82] In 2015 it was rated by The Daily Telegraph in an article about flops as the sixth worst West End musical so far. The Piccadilly followed it with a show rated by the Telegraph as the second worst:[81][n 1] Which Witch, received even worse reviews:[83] Michael Billington of The Guardian described the show as "three mind-numbing hours ... an all-too-graphic glimpse of purgatory" and two critics referred to it as "the musical from hell".[84] It opened on 22 October 1992 and ran for ten weeks, closing on 12 December.[85] In February 1993 a third musical in succession was staged at the Piccadilly – Robin: Prince of Sherwood. The production was notable for cheap ticket prices ("Kids all seats £5!") and for playing on Sundays – highly unusual in the West End[86] – but the show was not well received. The Stage remarked "Come back Which Witch, all is forgiven".[87] The show ran for four months.[88]

In December 1993 the Peter Hall Company presented Piaf by Pam Gems, with Elaine Paige as Edith Piaf.[89] When Paige left the cast in May 1994 bookings slumped and the show closed on 18 June.[90] Only the Lonely, a musical play about Roy Orbison, opened in September 1994 and ran until October the following year.[91] After prolonged negotiations the 1974 Broadway musical Mack and Mabel had its West End premiere at the Piccadilly on 7 November, running until 29 June 1996.[92]

On 11 September 1996 Matthew Bourne's award-winning production of Swan Lake, first seen at Sadler's Wells Theatre the previous November, opened at the Piccadilly. Ballet was a rarity in the commercial West End theatre, but Bourne had the support of the impresario Cameron Mackintosh.[93] The orchestra was reduced to thirty from the usual full symphonic forces, and the most remarked aspect of the production was the corps de ballet, consisting of bare-torsoed male dancers as the swans.[93] The production ran at the Piccadilly until 1 February 1997.[94]

Hall's company returned in March with Molière's The School for Wives, starring Peter Bowles and Eric Sykes,[95] which ran at the Piccadilly until the end of April, before transferring to the Comedy Theatre.[96] This was followed by a revival of Nell Dunn's comedy Steaming with Jenny Eclair, which ran from 16 May to 14 June 1997.[97] and then a limited twelve-week run from June to September of the 1977 musical Elvis.[98] Adventures in Motion Pictures returned in October, this time with their production of the ballet Cinderella, which ran until mid-January 1998.[99]

The Hall company returned again in March 1998, in association with the impresario Bill Kenwright,[100] for a year-long season that began with Waiting for Godot, with Alan Dobie and Julian Glover,[101] followed by Molière's The Misanthrope,[102] Shaw's Major Barbara,[103] Eduardo de Filippo's Filumena,[104] and Alan Bennett's Kafka's Dick.[105] After a brief run for Slava's Snowshow in March 1999,[106] Prunella Scales and Timothy West starred in Harold Pinter's The Birthday Party, which ran from 20 April to 3 July.[107] A jukebox musical, 4 Steps to Heaven, ran for a nine-week season from 27 July.[108] The last production of the 1990s at the Piccadilly was the musical Spend Spend Spend which opened in October and ran until August 2000.[109]

2000s

The musical La Cava transferred from the Victoria Palace Theatre, opening on 21 August 2000 for a six-month run.[110] After a short season of Shockheaded Peter between February and April 2001,[111][112] the National Theatre's revival of Michael Frayn's farce Noises Off played its first West End engagement from the 3rd May until 26 January 2002.[113] The Chichester Festival Theatre presented the London premiere of My One and Only for a six-month run from February 2002, 19 years after the show premiered on Broadway.[114] The English language premiere of the French musical Romeo and Juliet by Gérard Presgurvic opened on 4 November, though bad reviews resulted in its closing three months later.[115][116]

Ragtime, a musical, starred Maria Friedman and ran from 19 March 2003 to 14 June 2003.[117] Noises Off returned for a limited eight-week season, from 4 August to 8 November 2003,[118] and was followed by the National Theatre's production of Stoppard's comedy Jumpers, with Simon Russell Beale, which ran from 14 November 2003 to 6 March 2004.[119]

Jailhouse Rock – The Musical ran for a year, from 19 April 2004 to 23 April 2005,[120] and was followed by another musical, a revival of the 1950 show Guys and Dolls, which previewed from 18 May 2005, opened on 31 May, and ran until 14 April 2007; the opening cast included Ewan McGregor, Jane Krakowski, Jenna Russell and Douglas Hodge.[121] The last production of the 2000s was the musical Grease, which ran from 25 July 2007 to 30 April 2011.[122] The production ran for more than 1,300 performances and was the longest running show in the theatre's history.[123] The leads were cast via ITV's Grease Is the Word, with Danny Bayne and Susan McFadden playing Danny and Sandy.[124][125]

2010s

The first six productions of the 2010s at the Piccadilly were all musicals: Ghost the Musical (19 July 2011 – 6 October 2012);[126] Viva Forever (27 November 2012 – 29 June 2013);[127] Dirty Dancing (13 July 2013 – 22 February 2014);[128] Jersey Boys (15 March 2014 – 26 March 2017) based on the story of Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons; Annie (23 May 2017 – 18 February 2018;[129] and Strictly Ballroom, starring Will Young, which ran from 24 April to 27 October 2018.[130]

The other three productions at the theatre during the decade were all non-musical dramas. The first two were National Theatre productions in limited seasons, first The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (29 November 2018 – 27 April 2019);[131] and then The Lehman Trilogy (11 May 2019 – 31 August 2019), with Russell Beale, Adam Godley and Ben Miles;.[132] The third was Death of a Salesman (24 October 2019 – 4 January 2020), from the Young Vic, starring Wendell Pierce and Sharon D Clarke.[133]

2020s

Pretty Woman, starring Danny Mac and Aimie Atkinson previewed from 13 February and opened on 1 March 2020, but its run was curtailed within a fortnight, when West End theatres closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[134] (The show reopened at the Savoy in July 2021.) The Piccadilly reopened with the musical Moulin Rouge!, which previewed from 12 November 2021, opened in January 2022 and was due to run until 28 May,[135] but the run was extended and was still booking in September 2024.[136]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mander and Mitchenson (1975), p. 152

- ^ Hughes, p. 205

- ^ Gaye, p. 1531

- ^ "Chit Chat", The Stage, 11 November 1937, p. 10

- ^ a b Mander and Mitchenson (2000), p. 366

- ^ "Gielgud's 'Macbeth', with Walton music", The Sketch, 29 July 1942, p. 23

- ^ "Sunny River", The Tatler and Bystander, 18 August 1943, p. 199

- ^ Agate, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mander and Mitchenson (1975), p. 153

- ^ "Piccadilly Theatre", The Stage, 9 November 1943, p. 1

- ^ Gaye, p. 1536

- ^ "Chit Chat", The Stage, 22 March 1945, p. 4

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson (2000), p. 378–381

- ^ Brown, Ivor. "Theatre and Life", The Observer, 3 March 1946, p. 2

- ^ Reviews: The Manchester Guardian, 3 December 1946, p. 3; The Times, 21 December 1946, p. 6; and The Observer, 22 December 1946, p. 2

- ^ Brown, Ivor. "Two Westerners", The Observer, 13 July 1947, p. 2

- ^ "Chit Chat", The Stage, 1 July 1954, p. 8

- ^ "Joan Heal Wins Lead", The Stage, 24 May 1956, p. 12

- ^ Gaye, p. 1537

- ^ "Arsenic for the paying guest", The Tatler, 10 July 1957, p. 66; and Wearing (2024), p. 504

- ^ "The Rape of the Belt", The Stage, 21 November 1957, p. 15; and Wearing (2014), p. 538

- ^ "Hook, Line and Sinker", The Sphere, 22 November 1958, p. 316

- ^ "Theatres", The Daily Herald, 24 March 1959, p.

- ^ "Kay Hammond at her best in the Marriage-go-Round", The Stage, 5 November 1959, p. 17; and Wearing (2014), p. 674

- ^ "Not Much Can be Said For Bachelor Flat", The Stage, 2 June 1960, p. 17

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 20

- ^ "'The Playboy' still has great power and beauty", The Stage, 20 October 1960, p. 15; and Wearing (2021), p. 35

- ^ "Toys in the Attic", The Stage, 17 November 1960, p. 21

- ^ "Taking Over", The Stage, 19 January 1961, p. 14

- ^ "The Amorous Prawn", 15 February 1962, p. 8

- ^ Gaye, p. 1545

- ^ Wallace, Pat. "A bit too British", The Tatler, 24 October 1962, p. 253; Marriott, R. B. "Crusader who cleaned up New York", The Stage, 11 October 1962; Tynan, Kenneth. "A musical mayor transplanted", The Observer, 14 October 1962, p. 28; and Shulman, Milton. "Sorry, Fiorello! You'll have to do without my vote", The Evening Standard, 9 October 1962, p. 4

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 26 November 1962, p. 2; and Wearing (2021), p. 123

- ^ Trewin, J. C. "The World of the Theatre", Illustrated London News, 5 January 1963, p. 28; and "Chit Chat", The Stage, 14 February 1963, p. 8

- ^ "Cast change at the Piccadilly", The Stage, 30 April 1964, p. 1

- ^ Gaye, p. 1533; and "Lively numbers not enough", The Times, 5 August 1964, p. 11

- ^ "Infallible comedy", The Times, 25 November 1965, p. 5; and Mander and Mitchenson (1975), p. 153

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 466

- ^ Trewin, J. C. "The Young Visiters", Birmingham Daily Post, 24 December 1968, p. 19

- ^ "Return of Prospect", The Stage, 18 December 1969, p. 14

- ^ Hope-Wallace, Philip. "Vivat! Vivat! Regina!", The Guardian, 9 October 1970, p. 12; and Wearing, p. 474

- ^ "Edith Evans matchless in Anouilh", The Stage, 27 May 1971, p. 11: and "Glittering Anouilh from Chichester to the Piccadilly", The Stage, 11 November 1971, p. 15

- ^ Wearing (2021), pp. 523–524

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 539

- ^ "Transfer", The Stage, 16 March 1972, p. 8

- ^ "'Pull Both Ends' not so much a cracker, more a damp squib", The Stage, 27 July 1972, p. 13; and Mander and Mitchenson (1975), p. 154

- ^ Mander and Mitchenson (1975), p. 154; and Wearing (2021), p. 577

- ^ "Mother figure", The Guardian, 1 March 1973, p. 15; and Wearing (2021), p. 608

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 650

- ^ "Piccadilly", The Stage, 31 October 1974, p. 9; and Wearing (2021), p. 678

- ^ "Plays in Performance", The Stage, 7 January 1975. p. 7; and Wearing (2021), p. 686

- ^ "Plays in Performance", The Stage, 15 May 1975, p. 9; and Wearing (2021), p. 707

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 716

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 718

- ^ Cushman, Robert. "The pure in heart", The Observer, 23 March 1976, p. 29; and Wearing (2021), p. 756

- ^ "Today", The Guardian, 18 April 1977, p. 8; and Wearing (2021), p. 796

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 863

- ^ Cushman, Robert. "Back to New Orleans", The Observer, 20 August 1978, p. 21; and Wearing (2021), p. 896.

- ^ Wearing (2021), p. 896

- ^ Wearing (2021), pp. 916–918

- ^ "Theatre", The Daily Telegraph, 3 May 1979, p. 15; and Wearing (2021), p. 936

- ^ "Play reviews", The Stage, 7 June 1979, p. 33; and Wearing (2021), p. 941

- ^ "Production news", The Stage, 31 July 1980, p. 2; Wearing (2021), p. 1413; and "Theatre", Illustrated London News, 1 April 1981, p. 5

- ^ a b "£1.5 million revamp and a new show at the Piccadilly", The Stage, 20 January 1983, p. 1

- ^ "'i' cancellation costs backers £400,000", The Stage, 19 May 1983, p. 2

- ^ "Theatre Week", The Stage, 16 June 1983, p. 24

- ^ "Don't blame the critics", The Stage, 26 July 1984, p. 8

- ^ "Production news", The Stage, 30 May 1985, p. 2

- ^ "Bounty Bores", The Stage, 25 July 1985, p. 9; and "Daymas diary", The Stage, 6 November 1986, p. 38

- ^ "Frankie the slave whips up a frenzy", The Stage, 20 November 1986, p. 11

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 27 December 1986, p. 19

- ^ "Theatre", The Times, 17 February 1987, p. 16

- ^ "Theatre", The Times, 12 May 1987, p. 16

- ^ "Production news", The Stage, 21 May 1981, p. 9' and "Theatres", The Times, 14 September 1987, p. 18

- ^ "Theatre: London", The Times, 22 September 1987, p. 20; and "Theatre: London", The Times, 22 July 1988, p. 18

- ^ "Theatre: London", The Times, 8 August 1988, p. 16; and "Entertainments", The Times, 3 November 1988, p. 22

- ^ "City of dreadful night", The Times, 9 March 1989, p. 20; and "Musical closes after losses reach £2.5m", The Times, 22 August 1989, p. 20

- ^ "Theatre: London", The Times, 10 October 1989, p. 22; and "Theatre: London", The Times, 13 February 1990, p. 18

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 8 June 1990, p. 22, and 22 June 1991, p. 20

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 1 November 1991, p. 20

- ^ a b c Cavendish, Dominic. "The 10 worst musicals of all time" Archived 9 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph, 13 February 2015

- ^ Nightingale, Benedict. "Whale of a yarn drowns in an ocean of pointless mediocrity", The Times, 18 March 1992, p. 18; "Moby needs to camp out for a breath of fresh air", The Stage, 26 March 1992, p. 15; and "Entertainments", The Times, 30 June 1992, p. 36

- ^ De Jongh, Nicholas. "Witches who spell a disaster", The Evening Standard, 23 October 1992, p. 48; Nightingale, Benedict. "Dreams, drips and doggerel", The Times, 24 October 1992, p. 50; and Hepple, Peter. "Witch's brew spells disaster", The Stage, 5 November 1992, p. 13

- ^ Billington, Michael. "Theatre", The Guardian, 24 October 1992, p. 29; and Beaumont, Peter. "The musical from hell weathers fire and brimstone", The Observer, 1 November 1992, p. 9

- ^ "The witches are driven out of town by the critics", The Evening Standard, 9 December 1992, p. 3

- ^ "Entertainments", The Times, 19 April 1993, p. 32

- ^ Gould, Helen, "What a performance!", The Stage, 18 February 1993, p. 13

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 1 May 1993, p. 53

- ^ Nightingale, Benedict. "Provenance of the sparrow's fall", The Times 15 December 1993, p. 30

- ^ "Piaf show to close early", The Times, 31 May 1994, p. 2

- ^ "Production news", The Stage, 22 September 1994 and "Theatres", The Times, 4 October 1995, p. 36

- ^ "Mack and Mabel to debut in West End", The Stage, 22 June 1995; and "Entertainments", The Times, 26 June 1996, p. 42

- ^ a b Craine, Debra. "The death of dreams", The Times, 13 September 1996, p. 32

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 28 January 1997, p. 38

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 18 March 1997, p. 40

- ^ "Theatres", The Times 24 April 1997, p. 38, and 6 May 1997, p. 19

- ^ Nightingale, Benedict. "Wrinkles in the lines", The Times, 17 May 1997, p. 21; and "Theatres", The Times, 10 June 1997, p. 21

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 10 June 1997, p. 21

- ^ "Too much change", The Stage, 16 October 1997; and "Snaps", The Stage, 8 January 1998, p. 2

- ^ "Snaps", The Stage, 29 January 1998, p. 2

- ^ Thaxter, John. "Stretching the imagination", The Stage 19 March 1998, p. 13

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 2 April 1998, p. 38

- ^ Production news", The Stage, 16 April 1998, p. 39

- ^ "Theatre Week", The Stage, 8 October 1998, p. 47

- ^ "Theatre Week", The Stage, 19 November 1998, p. 43

- ^ "Snowshow was short on magic", The Stage, 11 March 1999, p. 21

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 10 April 1999, p. 140, and 3 July 1999, p. 21

- ^ "Production news", The Stage, 8 July 1999, p. 51

- ^ Hepple, Peter. "Piccadilly", The Stage, 21 October 1999, p. 12; and Baracaia, Alexa. "Fame cast feel in the dark over auditions", The Stage, 24 August 2000, p. 2

- ^ "Spanish La Cava Closes in London as French Napoleon Extends". Playbill.com. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Productions: Shockheaded Peter". thisistheatre.com. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "SHOCKHEADED PETER". Pomegranate Arts. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Productions: Noises Off". thisistheatre.com. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Production: My One and Only". thisistheatre.co.uk.

- ^ "Reviews: Romeo and Juliet - The Musical". LondonTheatre.co.uk.

- ^ "Production: Romeo and Juliet - The Musical". thisistheatre.co.uk.

- ^ Nightingale, Benedict. "A dance to the music of ragtime", The Times, 20 March 2003, p. 19; and "Entertainments", The Times, 9 June 2003

- ^ "Entertainments", The Times, 12 July 2003, and 10 November 2003, p. 56

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 3 November 2003, p. 58, and 6 March 2004, p. 113

- ^ "Jailhouse Rock", Theatricalia. Retrieved 24 June 2023

- ^ "Entertainments", The Times, 18 May 2005, p. 95; Nightingale, Benedict. "A pinch of Broadway pizzazz and a swinging good nature", The Times, 2 June 2005, p. 9; and "Guys and Dolls", The Times, 4 April 2007, p. 105

- ^ "Entertainments", The Times, 13 July 2007, p. 106, and 30 April 2011, p. 116

- ^ Shenton, Mark. "London Production of Grease to Shutter April 30, Prior to New U.K. Tour", Playbill.com, September 16, 2010

- ^ Atkins, Tom. "Review Round-Up of London Opening: Grease Not the Word for Critics" Archived September 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Whatsonstage.com, August 9, 2007

- ^ Grease in London ThisIsTheatre.com, retrieved March 9, 2010

- ^ Maxwell, Dominic. "A dazzling display of undying love", The Times, 20 July 2011, p. 19; and Bosanquet, Theo. Ghost the Musical confirms closing date at Piccadilly", WhatsOnStage.com, 14 June 2012

- ^ "Viva Forever, Musical Featuring Spice Girls Songs, Confirms West End Opening at Piccadilly Theatre". Playbill. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.; and Dirty Dancing to replace Viva Forever! in the West End, The Stage

- ^ "Entertainments", The Times, 8 July 2013, p. 82. and 22 February 2014, p. 76

- ^ "Miranda Hart to make West End debut in Annie musical" Archived 10 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 16 February 2017; and Craig Revel Horwood to replace Miranda Hart in Annie Archived 9 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, What's On Stage, 4 August 2017

- ^ "Strictly Ballroom to get its West End musical debut" Archived 29 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 14 February 2018; and "Strictly Ballroom The Musical to close 27 October" Archived 4 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Official London Theatre, 29 August 2018

- ^ "The Curious Incident", The Times, 22 September 2018, p. 91

- ^ "The Lehmann Trilogy" Archived 21 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, London Theatres. Retrieved 25 June 2023

- ^ "Death of a Salesman" Archived 21 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, London Theatres. Retrieved 25 June 2023

- ^ "Pretty Woman" Archived 3 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, London Theatres. Retrieved 25 June 2023

- ^ Wyver, Kate. " Moulin Rouge! The Musical review – wonderfully wild but close to karaoke" Archived 10 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 20 January 2022

- ^ "Calendar", Moulin Rouge, Piccadilly Theatre. Retrieved 25 June 2023

Sources

- Agate, James (1945). Immoment Toys: A Survey of Light Entertainment on the London Stage, 1920–1943. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 406504.

- Gaye, Freda, ed. (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.

- Hughes, Maureen (2009). The Pocket Guide to Plays and Playwrights. Barnsley: Remember When. ISBN 978-1-84-468043-6.

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (1975). The Theatres of London (second ed.). London: New English Library. ISBN 978-0-45-002123-7.

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (2000) [1957]. Theatrical Companion to Coward. Barry Day and Sheridan Morley (2000 edition, ed.) (second ed.). London: Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1-84002-054-0.

- Wearing, J. P. (2014). The London Stage 1950–1959: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. London: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-81-089308-5.

- Wearing, J. P. (2021). The London Stage 1960–1980: A Calendar of Dramatic Productions. London: Word Press. (no ISBN or OCLC)