FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

In hydrology, a main stem or mainstem (also known as a trunk) is "the primary downstream segment of a river, as contrasted to its tributaries".[1][2] The mainstem extends all the way from one specific headwater to the outlet of the river, although there are multiple ways to determine which headwater (or first-order tributary) is the source of the mainstem.[clarification needed] Water enters the mainstem from the river's drainage basin, the land area through which the mainstem and its tributaries flow.[3] A drainage basin may also be referred to as a watershed or catchment.[3]

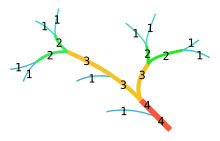

Hydrological classification systems assign numbers to tributaries and mainstems within a drainage basin. In the Strahler number, a modification of a system devised by Robert E. Horton in 1945, channels with no tributaries are called "first-order" streams. When two first-order streams meet, they are said to form a second-order stream; when two second-order streams meet, they form a third-order stream, and so on. In the Horton system, the entire mainstem of a drainage basin was assigned the highest number in that basin. However, in the Strahler system, adopted in 1957, only that part of the mainstem below the tributary of the next highest rank gets the highest number.[2]

In the United States, the Mississippi River mainstem achieves a Strahler number of 10, the highest in the nation. Eight rivers, including the Columbia River, reach 9. Streams with no tributaries, assigned the Strahler number 1, are most common. More than 1.5 million of these small streams, with average drainage basins of only 1 square mile (2.6 km2), have been identified in the United States alone.[2] Outside of the United States, the Amazon River reaches a Strahler number of 12, making it the highest-order river in the world.[4]

References

- ^ Benke, Arthur C. & Cushing, Colbert E., eds. (2005). Rivers of North America. Burlington, Massachusetts: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 1137. ISBN 0-12-088253-1.

- ^ a b c Patrick, Ruth (1995). Rivers of the United States: Volume II: Chemical and Physical Characteristics. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-471-10752-2.

- ^ a b Benke & Cushing (2005), p. 4.

- ^ Briney, Amanda. "How Are the World's Waterways Classified?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2018-12-24.