FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

The term Fourth Estate or fourth power refers to the press and news media in explicit capacity of reporting the News without advocacy nor framing political issues.[1] The derivation of the term arises from the traditional European concept of the three estates of the realm: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners.

The equivalent term "fourth power" is somewhat uncommon in English, but it is used in many European languages, including German (Vierte Gewalt), Italian (quarto potere), Spanish (Cuarto poder), French (Quatrième pouvoir), Swedish (tredje statsmakten [Third Estate]), Polish (Czwarta Władza), and Russian (четвёртая власть) to refer to a government's separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

The expression has also been applied to lawyers, to the British Queen Consort (acting as a free agent independent of her husband), and to the proletariat. But, generally, the term "Fourth Estate" refers to the press and media, emphasizing its role in monitoring and influencing the other branches of government and society. The concept originally comes from the idea of three estates in medieval European society:

First Estate: The Clergy - This group included religious leaders and institutions, which held significant power and influence over people's lives and societal norms.[2] Second Estate: The Nobility - This consisted of the aristocracy and landowners, who had political power and social status.[3] Third Estate: The Commoners - This group comprised the general populace, including peasants, merchants, and the burgeoning middle class, who were not part of the clergy or nobility.[4]

The "Fourth Estate" emerged with the rise of the press, which became a powerful force in shaping public opinion and holding other estates accountable. A "Fifth Estate," while it’s not traditionally recognized in the same way as the first four, some argue that modern digital media and the internet could be considered a Fifth Estate. This "Fifth Estate" includes bloggers, social media influencers, and other online platforms that can influence public discourse and politics independently of traditional media.[5][6][7]

Etymology

Oxford English Dictionary attributes, ("without confirmation") the origin of the term to Edmund Burke, who may have used it in a British parliamentary debate of 19–20 February 1771, on the opening up of press reporting of the House of Commons of Great Britain. Historian Thomas Carlyle reported the phrase in his account of the night's proceedings, published in 1840, attributing it to Burke.[8][9][10]

The press

In modern use, the term is applied to the press,[8] with the earliest use in this sense described by Thomas Carlyle in his book On Heroes and Hero Worship (1840): "Burke said there were Three Estates in Parliament; but, in the Reporters' Gallery yonder, there sat a Fourth Estate more important far than they all." (The three estates of the parliament of Britain were: the Lords Spiritual, the Lords Temporal and the Commons.)[9][12][8] If Burke made the statement Carlyle associates with him, Carlyle may have had the remark in mind when he wrote in his French Revolution (1837) that "A Fourth Estate, of Able Editors, springs up; increases and multiplies, irrepressible, incalculable."[13] In France the three estates of the French States-General were: the church, the nobility and enfranchised townsmen.[14]

Carlyle, however, may have mistaken his attribution: Thomas Macknight, writing in 1858, observes that Burke was merely a teller at the "illustrious nativity of the Fourth Estate".[10] If Burke is excluded, other candidates for coining the term are Henry Brougham speaking in Parliament in 1823 or 1824[15] and Thomas Macaulay in an essay of 1828 reviewing Hallam's Constitutional History: "The gallery in which the reporters sit has become a fourth estate of the realm."[16] In 1821, William Hazlitt applied the term to an individual journalist, William Cobbett, and the phrase soon became well established.[17][18]

In 1891, Oscar Wilde wrote:

In old days men had the rack. Now they have the Press. That is an improvement certainly. But still it is very bad, and wrong, and demoralizing. Somebody — was it Burke? — called journalism the fourth estate. That was true at the time no doubt. But at the present moment it is the only estate. It has eaten up the other three. The Lords Temporal say nothing, the Lords Spiritual have nothing to say, and the House of Commons has nothing to say and says it. We are dominated by Journalism.[19]

In United States English, the phrase "fourth estate" is contrasted with the "fourth branch of government", a term that originated because no direct equivalents to the estates of the realm exist in the United States. The "fourth estate" is used to emphasize the independence of the press, while the "fourth branch" suggests that the press is not independent of the government.[20]

The networked Fourth Estate

Yochai Benkler, author of the 2006 book The Wealth of Networks, described the "Networked Fourth Estate" in a May 2011 paper published in the Harvard Civil Liberties Review.[21] He explains the growth of non-traditional journalistic media on the Internet and how it affects the traditional press using WikiLeaks as an example. When Benkler was asked to testify in the United States vs. PFC Bradley E. Manning trial, in his statement to the morning 10 July 2013 session of the trial he described the Networked Fourth Estate as the set of practices, organizing models, and technologies that are associated with the free press and provide a public check on the branches of government.[22][23][24]: 28–29

It differs from the traditional press and the traditional fourth estate in that it has a diverse set of actors instead of a small number of major presses. These actors include small for-profit media organizations, non-profit media organizations, academic centers, and distributed networks of individuals participating in the media process with the larger traditional organizations.[22]: 99–100

Alternative meanings

Lawyers

In 1580 Michel de Montaigne proposed that governments should hold in check a fourth estate of lawyers selling justice to the rich and denying it to rightful litigants who do not bribe their way to a verdict:

What is more barbarous than to see a nation [...] where justice is lawfully denied him, that hath not wherewithall to pay for it; and that this merchandize hath so great credit, that in a politicall government there should be set up a fourth estate [tr. French: quatriesme estat (old orthography), quatrième état (modern)] of Lawyers, breathsellers and pettifoggers [...].

Michel de Montaigne, in the translation by John Florio, 1603.[25][26]

The proletariat

An early citation for this is Henry Fielding in The Covent Garden Journal (1752):

None of our political writers ... take notice of any more than three estates, namely, Kings, Lords, and Commons ... passing by in silence that very large and powerful body which form the fourth estate in this community ... The Mob.[27]

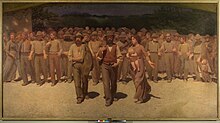

This sense has prevailed in other countries: In Italy, for example, striking workers in 1890s Turin were depicted as Il quarto stato—The Fourth Estate—in a painting by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo.[28] A political journal of the left, Quarto Stato, published in Milan, Italy, in 1926, also reflected this meaning.[29] In response to violence against a textile worker demonstration in Fourmies, France on May Day 1891, Georges Clemenceau said in a speech to the Chamber of Deputies:

Take care! The dead are strong persuaders. One must pay attention to the dead...I tell you that the primary fact of politics today is the inevitable revolution which is preparing...The Fourth Estate is rising and reaching for the conquest of power. One must take sides. Either you meet the Fourth Estate with violence or you welcome it with open arms. The moment has come to choose.[30]

Traditionalist philosopher Julius Evola saw the Fourth Estate as the final point of his historical cycle theory, the regression of the castes:

[T]here are four stages: in the first stage, the elite has a purely spiritual character, embodying what may be generally called "divine right." This elite expresses an ideal of immaterial virility. In the second stage, the elite has the character of warrior nobility; at the third stage we find the advent of oligarchies of a plutocratic and capitalistic nature, such as they arise in democracies; the fourth and last elite is that of the collectivist and revolutionary leaders of the Fourth Estate.

— Julius Evola, Men Among The Ruins, p. 164

British queens consort

In a parliamentary debate of 1789 Thomas Powys, 1st Baron Lilford, MP, demanded of minister William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham that he should not allow powers of regency to "a fourth estate: the queen".[31] This was reported by Burke, who, as noted above, went on to use the phrase with the meaning of "press".

U.S. Department of Defense

In the United States government's Department of Defense, the "fourth estate" (also called the "back office") refers to 28 agencies that do not fall under the Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. Examples include the Defense Technology Security Administration, Defense Technical Information Center, and Defense Information Systems Agency.[32][33]

Fiction

In his novel The Fourth Estate, Jeffrey Archer wrote: "In May 1789, Louis XVI summoned to Versailles a full meeting of the 'Estates General'. The First Estate consisted of three hundred clergy. The Second Estate, three hundred nobles. The Third Estate, commoners." The book is fiction based on the lives of two real-life press barons, Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch.[34]

See also

- Fourth branch of government

- Freedom of the press

- Fifth Estate

- Glossary of journalism

- Government by Journalism

- List of newspapers in the United States

- The Fourth Estate (2018 TV series)

References

- ^ "fourth estate". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Binski, Paul. Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation. Cornell University Press, 1996.

- ^ Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c.1300–c.1450. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- ^ Phillips, Seymour. The Medieval Peasant. Routledge, 2014.

- ^ Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- ^ Shirky, Clay. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. Penguin Books, 2008.

- ^ Bruns, Axel. Gatewatching and News Curation: Collected Essays on Journalism and Digital Communication. Peter Lang Publishing, 2015.

- ^ a b c "estate 7b". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Carlyle, Thomas (19 May 1840). "Lecture V: The Hero as Man of Letters. Johnson, Rousseau, Burns". On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History. Six Lectures. Reported with emendations and additions (Macmillan, 1901 ed.). London: James Fraser. p. 392. OCLC 2158602.

- ^ a b Macknight, Thomas (1858). "For the Liberty of the Press". History of the life and times of Edmund Burke. Vol. 1. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 462. OCLC 3565018.

- ^ "Origins – The Parliamentary Press Gallery". Parliamentary Press Gallery.

- ^ Wilding, Norman; Laundy, Philip (1958). "Estates of the Realm". An Encyclopædia of Parliament (1968 ed.). London: Cassell. p. 251.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas. "Chapter V. The Fourth Estate". The French Revolution. Vol. 1. Archived from the original on 22 January 2000. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Esmein (1911)

- ^ Ross, Charles (9 June 1855). "Replies to Minor Queries". Notes and Queries. 11 (294). London: William Thoms: 452. Ross (October 1800–6 December 1884) was chief parliamentary reporter for The Times.

- ^ Macaulay, Thomas (September 1828). "Hallam's constitutional history". The Edinburgh Review. 48. London: Longmans: 165.

- ^ Hazlitt, William (1835). Character of W. Cobbett M. P. Finsbury, London: J Watson. p. 3. OCLC 4451746.

He is too much for any single newspaper antagonist...He is a kind of fourth estate in the politics of the country.

- ^ de Montaigne, Michel; Cotton, Charles (1680). Hazlitt, William (ed.). The Complete Works of Michael de Montaigne (1842 ed.). London: J Templeman.

- ^ Wilde, Oscar (February 1891). "The Soul of Man under Socialism". Fortnightly Review. 49 (290): 292–319.

- ^ Martin A. Lee and Norman Solomon. Unreliable Sources (New York, NY: Lyle Stuart, 1990) ISBN 0-8184-0521-X

- ^ Benkler, Yochai (2011). "Free Irresponsible Press: Wikileaks and the Battle over the Soul of the Networked Fourth Estate". Harv. CR-CLL Rev. 46: 311. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b "US vs Bradley Manning, Volume 17 July 10, 2013 Afternoon Session". Freedom of the Press Foundation: Transcripts from Bradley Manning's Trial. 10 July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ "In The Matter Of: United States vs. PFC Bradley E. Manning - Unofficial Draft-07/10/13 Afternoon Session" (PDF). Freedom of the Press Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "US vs Bradley Manning, Volume 17 July 10, 2013 Morning Session" (PDF). Freedom of the Press Foundation: Transcripts from Bradley Manning's Trial. 10 July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ de Montaigne, Michel (1603). Saintsbury, George (ed.). The Essays of Montaigne done into English. Translated by Florio, John (1892 ed.). London: David Nutt. p. 115. OCLC 5339117.

- ^ For a more recent translation, see Hazlitt's edition of 1842: William Hazlitt, ed. (1842). The works of Montaigne. Vol. 1. London: John Templeman. p. 45. OCLC 951110840.

What can be more outrageous than to see a nation where, by lawful custom, the office of a Judge is to be bought and sold, where judgments are paid for with ready money, and where justice may be legally denied him that has not the wherewithal to pay...a fourth estate of wrangling lawyers to add to the three ancient ones of the church, nobility and people, which fourth estate, having the laws in their hands, and sovereign power over men's lives and fortunes, make a body separate from the nobility?

- ^ Fielding, Henry (13 June 1752). "O ye wicked rascallions". Covent Garden Journal (47). London., Quoted in OED "estate, n, 7b".

- ^ Paulicelli, Eugenia (2001). Barański, Zygmunt G.; West, Rebecca J. (eds.). The Cambridge companion to modern Italian culture. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-521-55982-9. For his painting, Pellizza transferred the action to his home village of Volpedo.

- ^ Pugliese, Stanislao G. (1999). Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0-674-00053-7.

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara (1962). The Proud Tower. Macmillan Publishing Company. p. 409.

- ^ Edmund Burke, ed. (1792). Dodsley's Annual Register for 1789. Vol. 31. London: J Dodsley. p. 112. The Whigs in parliament supported the transfer of power to the Regent, rather than the sick king's consort, Queen Charlotte.

- ^ "House proposal would eliminate DISA, 6 other agencies to save money in DoD". Federal News Network. 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Gould, Joe (26 July 2018). "The fate of DISA, and other org chart changes in the new defense policy bill". Defense News. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Lyngdoh, Andrew (17 May 2009). "The changing face of the Fourth Estate". Eastern Panorama. Shillong, India.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Esmein, Jean Paul Hippolyte Emmanuel Adhémar (1911). "States-General". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 803–805.