FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

| Chamise | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Adenostoma |

| Species: | A. fasciculatum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Adenostoma fasciculatum | |

| |

| Approximate distribution of Adenostoma fasciculatum in North America. | |

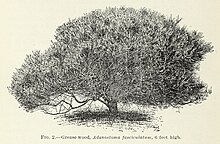

Adenostoma fasciculatum, commonly known as chamise or greasewood, is a flowering plant native to California and Baja California. This shrub is one of the most widespread plants of the California chaparral ecoregion. Chamise produces a specialized lignotuber underground and at the base of the stem, known as a burl, that allow it to resprout after fire has off burned its stems. It is noted for its greasy, resinous foliage, and its status as one of California's most iconic chaparral shrubs.[2]

Description

Morphology

It is a shrub with long, arching stems of brown to gray bark,[3] and is usually less than 4 meters high.[4] It is diffusely branched and spreading in habit, with some forms prostrate. The stems are slender, numerous, and erect, and generally lack permanent branches. The young stems have reddish bark, and become gray with exfoliating bark in later age.[5] The stems are resinous, oily, and glabrous to puberulent, with stipules less than 1.5 mm.[4] Emerging from the stems are alternate spirally arranged leaves, and sometimes branches. The leaves are linear, often 5 to 10 mm long, and shaped like needles.[5] They are shaped nearly round in cross section, and end apiculate, or with a sharp tip.[3] The leaves are evergreen, heavily sclerified,[6] and may also come in a sickle-shape.[4]

The inflorescence is dense to open, up to 17 cm long, and with 1 to 3 bractlets. Flowers are suspended on short pedicels 0 to 1.1 mm long.[4] The flowers are small, white, and inconspicuous yet showy.[5] The flowers have 5 petals and 5 calyx lobes, with the calyx lobes alternately arranged around the corolla.[3] The calyx lobes are wider than they are long.[4] There are 10 to 15 stamens, which occur in cylindrical to pyramid-shaped panicles at the tips of branches. The terminal clusters of flowers are 2.5 to 10 cm long.[5] The petals are retained into fruit maturation, turning a rusty brown color.[3] The hypanthium is 0.8 to 3.2 mm large, and strongly 10-ribbed.[4] The fruit is a small, ovoid achene, which develops within the hypanthium and disperses with the hypanthium as a single unit.[3]

Phytochemistry

Chamise contains terpenoids, which include the monoterpenoids hydroquinone and geranial, the diterpenoids thalianol and thaliandiol, and the triterpenoids 7α-hydroxybaruol and glutinol. Steroids like suberosol and campesterol also exist within the plant.[7] Various chemicals like p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, syringic acid, vanillic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid and arbutin have been identified within the plant.[8] Furthermore, umbelliferone and phlorizin were found. An unknown triterpenoid known as 7α-hydroxybaruol was first discovered in this plant.[7]

Taxonomy

Chamise is a member of the Rose family (Rosaceae), within the genus Adenostoma. The only other species in the genus is red-shanks (Adenostoma sparsifolium), which grows taller, has red-brown bark, and un-clustered, larger leaves.[3] Phylogenetic analysis places Adenostoma closest to Chamaebatiaria and Sorbaria, and suggests tentative placement in the subfamily Spiraeoideae, tribe Sorbarieae.[3]

Buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus) may be confused with chamise, as they both have profuse white flowers and are common in chaparral habitats.[9]

Etymology and nomenclature

The oily leaves and twigs gave rise to the common name "greasewood." The name fasciculatum originates from the clustered (fascicled) leaves on the plant.

- English: chamise, greasewood[10]

- Ko'alh: iipsi[11]

- Kumiai: iipshi, i.ipshí, ipxi[11]

- Spanish: chamizo, chamizo negro,[10] chamizo prieto,[11] yerba del pasma[6]

- Tiipai: iy pshii[11]

- Tongva language: huutah[12]

Varieties

There are varieties which differ from each other in minor characters; they are not accepted as distinct by all authors.[6] The following three taxa are recognized in the second edition of The Jepson Manual and the Flora of North America:[3]

- A. f. var. fasciculatum Hook. & Arn. (common chamise, California greasewood) – Leaves 5–10 mm, apex sharp; shoots hairless.[13] Occurs throughout California and in the northern Peninsular Ranges of Baja California.[10]

- A. f. var. obtusifolium S. Watson (San Diego chamise, southern chamise, southern greasewood) – Leaves 4–6 mm, apex blunt; shoots slightly hairy.[14] Found primarily in southern Orange County,[3] San Diego County[5] and Baja California, where it occurs as far south on the coast to El Rosario, but even further south on interior sky islands.[10] It usually prefers dry mesas or foothills along the coast, but may be found in some Peninsular Range mountains like San Jacinto,[3] or on the sky islands of the Sierra de La Asamblea and the Sierra de San Borja in the Baja California desert.[10]

- A. f. var. prostratum Dunkle (prostrate chamise, carpet chamise) – Similar to var. obtusifolium, but only grows in a prostrate form less than 0.5 m tall. Found on the Central Coast and Channel Islands, up to 750 m.[15]

Distribution and habitat

Chamise is probably the most widely distributed shrub of the chaparral ecosystem in North America, found throughout California and Baja California.[5] In California, it occurs from Mendocino County south to San Diego County, and is present in approximately 70% of California chaparral.[5] It occurs over a wide range of soils, elevations, latitudes, and distances from the coasts, at elevations as high as 1,800 meters. In Baja California, it is found in the Peninsular Ranges of the Sierra de Juarez and Sierra de San Pedro Martir, along with the sky islands of the Sierra de La Asamblea and the Sierra de San Borja in the Central Desert.[10]

This plant is typically found along foothills and coastal mountains, ridges, mesas, and hot, xeric sites.[5] It dominates dry south and west-facing slopes, and survives in an average temperature range between 0 °C to 38 °C. In the southern Coast Ranges, where annual rainfall may average between 400 and 500 mm, chamise can be found abundantly on all slopes and exposures, and grows on both deep, fertile soils and shallow, rocky soils.[5] As the amount of precipitation increases with northward latitude, chamise is restricted to poorer soils and drier, exposed sites.[5]

Ecology

Reproductive biology

Chamise may reproduce both sexually and vegetatively. Seedling recruitment and population expansion is typically reliant on wildfire, but a dimorphic population of both dormant and as well as germinable seeds are prepared to sprout in suitable conditions.[5] The seeds are shade intolerant, only emerging where there are openings in the canopy. Seed production in mature shrubs does not decrease relative to the age of plants.[3] Vegetative reproduction is by canopy rejuvenation from the burl, via the production of new basal sprouts, which may be induced by fire or mechanical means.[5] Although the plants regenerate vegetatively, they do not spread vegetatively.[3]

Chamise tends to have a high proportion of sterile fruits. This may be due to under-pollination, limited resources, or consequences of a high genetic load. Chamise is a self-incompatible plant, and allozyme analysis of chamise populations have shown a high rate of outcrossing.[3]

Dormant seeds tend to accumulate in the soil, until they are disturbed by a wildfire.[5] Around 90% of seeds will germinate after exposure to fire, but establishment from seeds is episodic. Seedling survival rates will decrease substantially following a fire, with only up to 1% of seedlings surviving five years after a fire. Second year survival after fires for seedlings seems to be much higher in Southern California, at about 50 to 62%. Seedling growth occurs in late winter and spring, and plants grown from seed reach reproductive maturity within three to four years. However, most postfire seedlings may fail to even reach maturity after germination, being negatively correlated with the regeneration of the burls. Many seedlings will fail after finding themselves in competition with healthy burls after a fire.[3]

Seasonal development

The plant flowers from April to June, peaking in May. Growth is typically initiated in January, speeding up in March, peaking in May, and then ending in July. Root growth follows a similar pattern, but fine roots may grow following summer rain events. Plants can remain physiologically active in summer drought due to their deep tap roots being able to bring up moisture deep within the earth, and because their fine shallow roots are able to make quick use of infrequent moisture. Plants that have been burned to the burl may continue to expend growth even into summer.[3]

Upon fruit dispersal in summer, any old inflorescences are shed, and new growth becomes woody. The production of the next inflorescences and flowers continues even in conditions of drought or extreme heat, owing to the storage of nutrients in the burl that enable the plant to continue production of the sexual organs. New foliage is also not limited to drought conditions or young stems, with leaves emerging from stems up to 8 or 9 years old. The leaves are retained for up to two growing seasons. Production of the sexual organs is usually prioritized over the development of new branches or foliage.[5]

Habitat ecology

Chamise forms dense, monotypic stands that cover the dry hills of coastal California. These thickets of chamise are sometimes called chamissal[6] or chamise chaparral.[2] In this chaparral type toyon,[16] scrub oak, ceanothus and manzanita may also be co-dominant.[2]

It is very drought tolerant and adaptable, with the ability to grow in nutrient-poor, barren soil and on exposed, dry, rocky outcrops. It can be found in serpentine soils and south-facing slopes, which are generally inhospitable to most plants, as well as in slate, sand, clay, and gravel soils. Chaparral habitats are known for their fierce periodical wildfires, and like other chaparral flora, chamise dries out, burns, and recovers quickly to thrive once again. It is a plant that controls erosion well, sprouting from ground level in low basal crowns that remain after fires, preventing the bare soil from being washed away.[3]

Chamise is an important plant for wildlife. After wildfires, the resprouting chamise may provide nearly all of the available forage for animals. Chamise sprouts are browsed by mule deer and likely rabbits, but may be unpalatable to other mammals. Dusky-footed woodrats will store the bark and leaves as food in their nests year-round. Chamise and chamissal provides habitat and cover for nesting birds, mule deer, and sensitive species of wildlife such as the orange-throated whiptail lizard, and the California gnatcatcher.[3]

Uses

Ethnobotany

Tongva

The plant is considered a useful medicinal plant by the Tongva who know the plant as huutah. They use the oils from the twigs and leaves and make a strong tea from the bark for the treatment of skin infections. For sores and snakebites, the leaves and twigs are ground into a powder and mixed with animal grease and applied. The branches and leaves may be boiled which produces a liquid that can be used to bathe sore, swollen, or infected parts of the body. Huutah is also made into a tea to relieve cramps, ulcers, and chest ailments.[12]

Kumeyaay

The Kumeyaay and associated peoples have numerous uses for chamise, which they call iipsi or iipshi. The presence of the flammable oils in the leaves and stems make the sticks an excellent choice for kindling. The tough lignotuber, or the burl, is valued for creating long-lasting and high quality charcoal when burned. The Kumeyaay also used chamise for making hardwood points of arrows. The chamise-wood point would be pressed or glued with pinyon pine pitch into a shaft made out of arrowweed, California sunflower, or mulefat. Fire was used to harden the wooden points, which allegedly made it as hard as iron as when done correctly.[11]

The plant is also used by many other Native Americans including the Cahuilla, Chumash and the Ohlone.[17]

Medicinal

Chamise is useful for treating eczema and skin conditions caused by chafing and irritation. Psoriasis plaques do not seem to respond well to chamise treatment, but this treatment reportedly improved discomfort and dryness.[7] A balm is made by placing 50 grams of branches and leaves into 2 liters of extra virgin olive oil to infuse for 1 month. Then the olive oil is poured into a mixing bowl and 135 grams of beeswax is melted and thoroughly mixed in a water bath at 75 degrees Celsius. The mixture is then poured into 35 milliliter containers and allowed to harden into a balm. The balm can be rubbed with the finger tips and used as needed daily on rashes and lesions on the skin.[18]

References

- ^ "Plant profile for Adenostoma fasciculatum". USDA. 2008.

- ^ a b c Rundel, P. W. (2018). California chaparral and its global significance. In Valuing Chaparral (pp. 7). Springer, Cham.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Montalvo, A.M.; Riordan, E.C.; Beyers, Jan (2017). "Plant profile for Adenostoma fasciculatum" (PDF). Treesearch. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-19. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Jones, William (2012). "Adenostoma fasciculatum". Jepson eFlora. Jepson Flora Project. Archived from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n McMurray, Nancy E. (1990) Adenostoma fasciculatum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Retrieved 15 October 2021

- ^ a b c d Pasiecznik, Nick (28 January 2015). "Adenostoma fasciculatum (chamise)". CABI Invasive Species Compendium. CABI International. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Adams, J., Bouttemy, A., Filho, O. R. F., & Williams, T. (2014). Adenostoma Fasciculatum, California Chamise, Chemistry and Use in Skin Conditions. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY), 20(5), A35.

- ^ McPherson, J. K., Chou, C. H., & Muller, C. H. (1971). Allelopathic constituents of the chaparral shrub Adenostoma fasciculatum. Phytochemistry, 10(12), 2925-2933.

- ^ "Ceanothus cuneatus var. Cuneatus Calflora".

- ^ a b c d e f Rebman, J. P.; Gibson, J.; Rich, K. (2016). "Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California, Mexico" (PDF). San Diego Society of Natural History. 45: 244.

- ^ a b c d e Wilken, Michael A. (2012) An Ethnobotany of Baja California's Kumeyaay Indians. Retrieved 15 October 2021

- ^ a b "Huutah". Tongva Medicinal Plants.

- ^ Jones, William (2012). "Adenostoma fasciculatum var. fasciculatum". Jepson eFlora. Jepson Flora Project. Archived from the original on 2017-06-29. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Jones, William (2012). "Adenostoma fasciculatum var. obtusifolium". Jepson eFlora. Jepson Flora Project. Archived from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Jones, William (2012). "Adenostoma fasciculatum var. prostratum". Jepson eFlora. Jepson Flora Project. Archived from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008). N. Stromberg (ed.). "Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia)". Global Twitcher. Archived from the original on 2009-07-19.

- ^ "Adenostoma fasciculatum". Native American Ethnobotany Database.

- ^ Adams, JD (2014). "What can traditional healing do for modern medicine" (PDF). Tang (Humanitas Medicine). 4 (2): 9.1 – 9.6. doi:10.5667/tang.2014.0006. S2CID 72461373.