FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

Cation–π interaction is a noncovalent molecular interaction between the face of an electron-rich π system (e.g. benzene, ethylene, acetylene) and an adjacent cation (e.g. Li+, Na+). This interaction is an example of noncovalent bonding between a monopole (cation) and a quadrupole (π system). Bonding energies are significant, with solution-phase values falling within the same order of magnitude as hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. Similar to these other non-covalent bonds, cation–π interactions play an important role in nature, particularly in protein structure, molecular recognition and enzyme catalysis. The effect has also been observed and put to use in synthetic systems.[1][2]

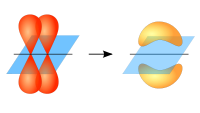

Origin of the effect

Benzene, the model π system, has no permanent dipole moment, as the contributions of the weakly polar carbon–hydrogen bonds cancel due to molecular symmetry. However, the electron-rich π system above and below the benzene ring hosts a partial negative charge. A counterbalancing positive charge is associated with the plane of the benzene atoms, resulting in an electric quadrupole (a pair of dipoles, aligned like a parallelogram so there is no net molecular dipole moment). The negatively charged region of the quadrupole can then interact favorably with positively charged species; a particularly strong effect is observed with cations of high charge density.[2]

Nature of the cation–π interaction

The most studied cation–π interactions involve binding between an aromatic π system and an alkali metal or nitrogenous cation. The optimal interaction geometry places the cation in van der Waals contact with the aromatic ring, centered on top of the π face along the 6-fold axis.[3] Studies have shown that electrostatics dominate interactions in simple systems, and relative binding energies correlate well with electrostatic potential energy.[4][5]

The Electrostatic Model developed by Dougherty and coworkers describes trends in binding energy based on differences in electrostatic attraction. It was found that interaction energies of cation–π pairs correlate well with electrostatic potential above the π face of arenes: for eleven Na+-aromatic adducts, the variation in binding energy between the different adducts could be completely rationalized by electrostatic differences. Practically, this allows trends to be predicted qualitatively based on visual representations of electrostatic potential maps for a series of arenes. Electrostatic attraction is not the only component of cation–π bonding. For example, 1,3,5-trifluorobenzene interacts with cations despite having a negligible quadrupole moment. While non-electrostatic forces are present, these components remain similar over a wide variety of arenes, making the electrostatic model a useful tool in predicting relative binding energies. The other "effects" contributing to binding are not well understood. Polarization, donor-acceptor[permanent dead link] and charge-transfer interactions have been implicated; however, energetic trends do not track well with the ability of arenes and cations to take advantage of these effects. For example, if induced dipole was a controlling effect, aliphatic compounds such as cyclohexane should be good cation–π partners (but are not).[4]

The cation–π interaction is noncovalent and is therefore fundamentally different than bonding between transition metals and π systems. Transition metals have the ability to share electron density with π-systems through d-orbitals, creating bonds that are highly covalent in character and cannot be modeled as a cation–π interaction.

Factors influencing the cation–π bond strength

Several criteria influence the strength of the bonding: the nature of the cation, solvation effects, the nature of the π system, and the geometry of the interaction.

Nature of the cation

From electrostatics (Coulomb's law), smaller and more positively charged cations lead to larger electrostatic attraction. Since cation–π interactions are predicted by electrostatics, it follows that cations with larger charge density interact more strongly with π systems.

The following table shows a series of Gibbs free energy of binding between benzene and several cations in the gas phase.[2][6] For a singly charged species, the gas-phase interaction energy correlates with the ionic radius, (non-spherical ionic radii are approximate).[7][8]

M+ Li+ Na+ K+ NH4+ Rb+ NMe4+ –ΔG [kcal/mol] 38 27 19 19 16 9 [Å] 0.76 1.02 1.38 1.43 1.52 2.45

This trend supports the idea that coulombic forces play a central role in interaction strength, since for other types of bonding one would expect the larger and more polarizable ions to have greater binding energies.

Solvation effects

The nature of the solvent also determines the absolute and relative strength of the bonding. Most data on cation–π interaction is acquired in the gas phase, as the attraction is most pronounced in that case. Any intermediating solvent molecule will attenuate the effect, because the energy gained by the cation–π interaction is partially offset by the loss of solvation energy.

For a given cation–π adduct, the interaction energy decreases with increasing solvent polarity. This can be seen by the following calculated interaction energies of methylammonium and benzene in a variety of solvents.[9]

Additionally, the trade-off between solvation and the cation–π effect results in a rearrangement of the order of interaction strength for a series of cations. While in the gas phase the most densely charged cations have the strongest cation–π interaction, these ions also have a high desolvation penalty. This is demonstrated by the relative cation–π bond strengths in water for alkali metals:[10]

Nature of the π system

Quadrupole moment

Comparing the quadrupole moment of different arenes is a useful qualitative tool to predict trends in cation–π binding, since it roughly correlates with interaction strength. Arenes with larger quadrupole moments are generally better at binding cations.

However, a quadrupole-ion model system cannot be used to quantitatively model cation–π interactions. Such models assume point charges, and are therefore not valid given the short cation–π bond distance. In order to use electrostatics to predict energies, the full electrostatic potential surface must be considered, rather than just the quadrupole moment as a point charge.[2]

Substituents on the aromatic ring

The electronic properties of the substituents also influence the strength of the attraction.[11] Electron withdrawing groups (for example, cyano −CN) weaken the interaction, while electron donating substituents (for example, amino −NH2) strengthen the cation–π binding. This relationship is illustrated quantitatively in the margin for several substituents.

The electronic trends in cation–π binding energy are not quite analogous to trends in aryl reactivity. Indeed, the effect of resonance participation by a substituent does not contribute substantively to cation–π binding, despite being very important in many chemical reactions with arenes. This was shown by the observation that cation–π interaction strength for a variety of substituted arenes correlates with the σmeta Hammett parameter. This parameter is meant to illustrate the inductive effects of functional groups on an aryl ring.[4]

The origin of substituent effects in cation–π interactions has often been attributed to polarization from electron donation or withdrawal into or out of the π system.[12] This explanation makes intuitive sense, but subsequent studies have indicated that it is flawed. Recent computational work by Wheeler and Houk strongly indicate that the effect is primarily due to direct through-space interaction between the cation and the substituent dipole. In this study, calculations that modeled unsubstituted benzene plus interaction with a molecule of "H-X" situated where a substituent would be (corrected for extra hydrogen atoms) accounted for almost all of the cation–π binding trend. For very strong pi donors or acceptors, this model was not quite able account for the whole interaction; in these cases polarization may be a more significant factor.[5]

Binding with heteroaromatic systems

Heterocycles are often activated towards cation–π binding when the lone pair on the heteroatom is in incorporated into the aromatic system (e.g. indole, pyrrole). Conversely, when the lone pair does not contribute to aromaticity (e.g. pyridine), the electronegativity of the heteroatom wins out and weakens the cation–π binding ability.

Since several classically "electron rich" heterocycles are poor donors when it comes to cation–π binding, one cannot predict cation–π trends based on heterocycle reactivity trends. Fortunately, the aforementioned subtleties are manifested in the electrostatic potential surfaces of relevant heterocycles.[2]

cation–heterocycle interaction is not always a cation–π interaction; in some cases it is more favorable for the ion to be bound directly to a lone pair. For example, this is thought to be the case in pyridine-Na+ complexes.

Geometry

cation–π interactions have an approximate distance dependence of 1/rn where n<2. The interaction is less sensitive to distance than a simple ion-quadrupole interaction which has 1/r3 dependence.[13]

A study by Sherrill and coworkers probed the geometry of the interaction further, confirming that cation–π interactions are strongest when the cation is situated perpendicular to the plane of atoms (θ = 0 degrees in the image below). Variations from this geometry still exhibit a significant interaction which weakens as θ angle approaches 90 degrees. For off-axis interactions the preferred ϕ places the cation between two H atoms. Equilibrium bond distances also increase with off-axis angle. Energies where the cation is coplanar with the carbon ring are saddle points on the potential energy surface, which is consistent with the idea that interaction between a cation and the positive region of the quadrupole is not ideal.[14]

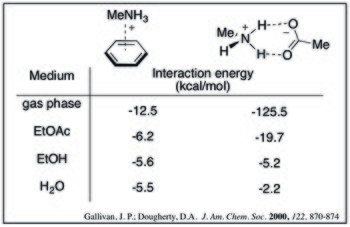

Relative interaction strength

Theoretical calculations suggest the cation–π interaction is comparable to (and potentially stronger than) ammonium-carboxylate salt bridges in aqueous media. Computed values below show that as solvent polarity increases, the strength of the cation–π complex decreases less dramatically. This trend can be rationalized by desolvation effects: salt bridge formation has a high desolvation penalty for both charged species whereas the cation–π complex would only pay a significant penalty for the cation.[9]

In nature

Nature's building blocks contain aromatic moieties in high abundance. Recently, it has become clear that many structural features that were once thought to be purely hydrophobic in nature are in fact engaging in cation–π interactions. The amino acid side chains of phenylalanine, tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine, are capable of binding to cationic species such as charged amino acid side chains, metal ions, small-molecule neurotransmitters and pharmaceutical agents. In fact, macromolecular binding sites that were hypothesized to include anionic groups (based on affinity for cations) have been found to consist of aromatic residues instead in multiple cases. Cation–π interactions can tune the pKa of nitrogenous side-chains, increasing the abundance of the protonated form; this has implications for protein structure and function.[15] While less studied in this context, the DNA bases are also able to participate in cation–π interactions.[16][17]

Role in protein structure

Early evidence that cation–π interactions played a role in protein structure was the observation that in crystallographic data, aromatic side chains appear in close contact with nitrogen-containing side chains (which can exist as protonated, cationic species) with disproportionate frequency.

A study published in 1986 by Burley and Petsko looked at a diverse set of proteins and found that ~ 50% of aromatic residues Phe, Tyr, and Trp were within 6Å of amino groups. Furthermore, approximately 25% of nitrogen containing side chains Lys, Asn, Gln, and His were within van der Waals contact with aromatics and 50% of Arg in contact with multiple aromatic residues (2 on average).[18]

Studies on larger data sets found similar trends, including some dramatic arrays of alternating stacks of cationic and aromatic side chains. In some cases the N-H hydrogens were aligned toward aromatic residues, and in others the cationic moiety was stacked above the π system. A particularly strong trend was found for close contacts between Arg and Trp. The guanidinium moiety of Arg in particular has a high propensity to be stacked on top of aromatic residues while also hydrogen-bonding with nearby oxygen atoms.[19][20][21]

Molecular recognition and signaling

An example of cation–π interactions in molecular recognition is seen in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) which binds its endogenous ligand, acetylcholine (a positively charged molecule), via a cation–π interaction to the quaternary ammonium. The nAChR neuroreceptor is a well-studied ligand-gated ion channel that opens upon acetylcholine binding. Acetylcholine receptors are therapeutic targets for a large host of neurological disorders, including Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia, depression and autism. Studies by Dougherty and coworkers confirmed that cation–π interactions are important for binding and activating nAChR by making specific structural variations to a key tryptophan residue and correlating activity results with cation–π binding ability.[22]

The nAChR is especially important in binding nicotine in the brain, and plays a key role in nicotine addiction. Nicotine has a similar pharmacophore to acetylcholine, especially when protonated. Strong evidence supports cation–π interactions being central to the ability of nicotine to selectively activate brain receptors without affecting muscle activity.[23][24]

A further example is seen in the plant UV-B sensing protein UVR8. Several tryptophan residues interact via cation–π interactions with arginine residues which in turn form salt bridges with acidic residues on a second copy of the protein. It has been proposed[25] that absorption of a photon by the tryptophan residues disrupts this interaction and leads to dissociation of the protein dimer.

Cation–π binding is also thought to be important in cell-surface recognition[2][26]

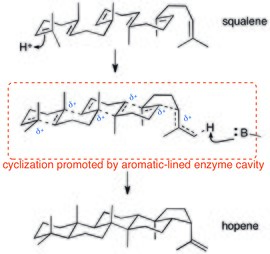

Enzyme catalysis

Cation–π interactions can catalyze chemical reactions by stabilizing buildup of positive charge in transition states. This kind of effect is observed in enzymatic systems. For example, acetylcholine esterase contains important aromatic groups that bind quaternary ammonium in its active site.[2]

Polycyclization enzymes also rely on cation–π interactions. Since proton-triggered polycyclizations of squalene proceed through a (potentially concerted) cationic cascade, cation–π interactions are ideal for stabilizing this dispersed positive charge. The crystal structure of squalene-hopene cyclase shows that the active site is lined with aromatic residues.[27]

In synthetic systems

Solid state structures

Cation–π interactions have been observed in the crystals of synthetic molecules as well. For example, Aoki and coworkers compared the solid state structures of Indole-3-acetic acid choline ester and an uncharged analogue. In the charged species, an intramolecular cation–π interaction with the indole is observed, as well as an interaction with the indole moiety of the neighboring molecule in the lattice. In the crystal of the isosteric neutral compound the same folding is not observed and there are no interactions between the tert-butyl group and neighboring indoles.[28]

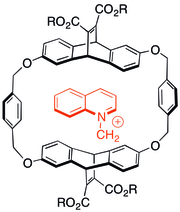

Supramolecular receptors

Some of the first studies on the cation–π interaction involved looking at the interactions of charged, nitrogenous molecules in cyclophane host–guest chemistry. It was found that even when anionic solubilizing groups were appended to aromatic host capsules, cationic guests preferred to associate with the π-system in many cases. The type of host shown to the right was also able to catalyze N-alkylation reactions to form cationic products.[29]

More recently, cation–π centered substrate binding and catalysis has been implicated in supramolecular metal-ligand cluster catalyst systems developed by Raymond and Bergman.[30]

Use of π-π, CH-π, and π-cation interactions in supramolecular assembly

π-systems are important building blocks in supramolecular assembly because of their versatile noncovalent interactions with various functional groups. Particularly, π-π, CH-π, and π-cation interactions are widely used in supramolecular assembly and recognition.

π-π interaction concerns the direct interactions between two &pi-systems; and cation–π interaction arises from the electrostatic interaction of a cation with the face of the π-system. Unlike these two interactions, the CH-π interaction arises mainly from charge transfer between the C-H orbital and the π-system.

A notable example of applying π-π interactions in supramolecular assembly is the synthesis of catenane. The major challenge for the synthesis of catenane is to interlock molecules in a controlled fashion. Stoddart and co-workers developed a series of systems utilizing the strong π-π interactions between electron-rich benzene derivatives and electron-poor pyridinium rings.[31] [2]Catanene was synthesized by reacting bis(pyridinium) (A), bisparaphenylene-34-crown-10 (B), and 1, 4-bis(bromomethyl)benzene C (Fig. 2). The π-π interaction between A and B directed the formation of an interlocked template intermediate that was further cyclized by substitution reaction with compound C to generate the [2]catenane product.

Organic synthesis and catalysis

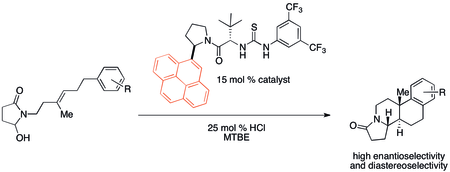

Cation–π interactions have likely been important, though unnoticed, in a multitude of organic reactions historically. Recently, however, attention has been drawn to potential applications in catalyst design. In particular, noncovalent organocatalysts have been found to sometimes exhibit reactivity and selectivity trends that correlate with cation–π binding properties. A polycyclization developed by Jacobsen and coworkers shows a particularly strong cation–π effect using the catalyst shown below.[32]

Anion–π interaction

In many respects, anion–π interaction is the opposite of cation–π interaction, although the underlying principles are identical. Significantly fewer examples are known to date. In order to attract a negative charge, the charge distribution of the π system has to be reversed. This is achieved by placing several strong electron withdrawing substituents along the π system (e. g. hexafluorobenzene).[33] The anion–π effect is advantageously exploited in chemical sensors for specific anions.[34]

See also

References

- ^ Eric V. Anslyn; Dennis A. Dougherty (2004). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dougherty, D. A.; J.C. Ma (1997). "The Cation–π Interaction". Chemical Reviews. 97 (5): 1303–1324. doi:10.1021/cr9603744. PMID 11851453.

- ^ Tsuzuki, Seiji; Yoshida, Masaru; Uchimaru, Tadafumi; Mikami, Masuhiro (2001). "The Origin of the Cation/π Interaction: The Significant Importance of the Induction in Li+and Na+Complexes". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 105 (4): 769–773. Bibcode:2001JPCA..105..769T. doi:10.1021/jp003287v.

- ^ a b c d S. Mecozzi; A. P. West; D. A. Dougherty (1996). "Cation–π Interactions in Simple Aromatics: Electrostatics Provide a Predictive Tool". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 118 (9): 2307–2308. doi:10.1021/ja9539608.

- ^ a b S. E. Wheeler; K. N. Houk (2009). "Substituent Effects in Cation/π Interactions and Electrostatic Potentials above the Center of Substituted Benzenes Are Due Primarily to through-Space Effects of the Substituents". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (9): 3126–7. doi:10.1021/ja809097r. PMC 2787874. PMID 19219986.

- ^ J. C. Amicangelo; P. B. Armentrout (2000). "Absolute Binding Energies of Alkali-Metal Cation Complexes with Benzene Determined by Threshold Collision-Induced Dissociation Experiments and ab Initio Theory". J. Phys. Chem. A. 104 (48): 11420–11432. Bibcode:2000JPCA..10411420A. doi:10.1021/jp002652f.

- ^ Robinson RA, Stokes RH. Electrolyte solutions. UK: Butterworth Publications, Pitman, 1959.

- ^ Clays and Clay Minerals, Vol.45, No. 6, 859-866, 1997.

- ^ a b Gallivan, Justin P.; Dougherty, Dennis A. (2000). "A Computational Study of Cation−π Interactions vs Salt Bridges in Aqueous Media: Implications for Protein Engineering" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 122 (5): 870–874. doi:10.1021/ja991755c.

- ^ Kumpf, R.; Dougherty, D. (1993). "A mechanism for ion selectivity in potassium channels: Computational studies of cation–pi interactions". Science. 261 (5129): 1708–10. Bibcode:1993Sci...261.1708K. doi:10.1126/science.8378771. PMID 8378771.

- ^ Raju, Rajesh K.; Bloom, Jacob W. G.; An, Yi; Wheeler, Steven E. (2011). "Substituent Effects on Non-Covalent Interactions with Aromatic Rings: Insights from Computational Chemistry". ChemPhysChem. 12 (17): 3116–30. doi:10.1002/cphc.201100542. PMID 21928437.

- ^ Hunter, C. A.; Low, C. M. R.; Rotger, C.; Vinter, J. G.; Zonta, C. (2002). "Supramolecular Chemistry and Self-assembly Special Feature: Substituent effects on cation–pi interactions: A quantitative study". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (8): 4873–4876. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.4873H. doi:10.1073/pnas.072647899. PMC 122686. PMID 11959939.

- ^ Dougherty, Dennis A. (1996). "cation–pi interactions in chemistry and biology: A new view of benzene, Phe, Tyr, and Trp". Science. 271 (5246): 163–168. Bibcode:1996Sci...271..163D. doi:10.1126/science.271.5246.163. PMID 8539615. S2CID 9436105.

- ^ Marshall, Michael S.; Steele, Ryan P.; Thanthiriwatte, Kanchana S.; Sherrill, C. David (2009). "Potential Energy Curves for Cation−π Interactions: Off-Axis Configurations Are Also Attractive". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 113 (48): 13628–32. Bibcode:2009JPCA..11313628M. doi:10.1021/jp906086x. PMID 19886621.

- ^ Lund-Katz, S; Phillips, MC; Mishra, VK; Segrest, JP; Anantharamaiah, GM (1995). "Microenvironments of basic amino acids in amphipathic alpha-helices bound to phospholipid: 13C NMR studies using selectively labeled peptides". Biochemistry. 34 (28): 9219–9226. doi:10.1021/bi00028a035. PMID 7619823.

- ^ M. M. Gromiha; C. Santhosh; S. Ahmad (2004). "Structural analysis of cation–π interactions in DNA binding proteins". Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 34 (3): 203–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2004.04.003. PMID 15225993.

- ^ J. P. Gallivan; D. A. Dougherty (1999). "Cation–π interactions in structural biology". PNAS. 96 (17): 9459–9464. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.9459G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.17.9459. PMC 22230. PMID 10449714.

- ^ Burley, SK; Petsko, GA (1986). "Amino-aromatic interactions in proteins". FEBS Lett. 203 (2): 139–143. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(86)80730-X. PMID 3089835.

- ^ Brocchieri, L; Karlin, S (1994). "Geometry of interplanar residue contacts in protein structures". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91 (20): 9297–9301. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.9297B. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.20.9297. PMC 44799. PMID 7937759.

- ^ Karlin, S; Zuker, M; Brocchieri, L (1994). "Measuring residue associations in protein structures. Possible implications for protein folding". J. Mol. Biol. 239 (2): 227–248. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1365. PMID 8196056.

- ^ Nandi, CL; Singh, J; Thornton, JM (1993). "Atomic environments of arginine side chains in proteins". Protein Eng. 6 (3): 247–259. doi:10.1093/protein/6.3.247. PMID 8506259.

- ^ Zhong, W; Gallivan, JP; Zhang, Y; Li, L; Lester, HA; Dougherty, DA (1998). "From ab initio quantum mechanics to molecular neurobiology: A cation–π binding site in the nicotinic receptor". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95 (21): 12088–12093. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9512088Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.21.12088. PMC 22789. PMID 9770444.

- ^ D. L. Beene; G. S. Brandt; W. Zhong; N. M. Zacharias; H. A. Lester; D. A. Dougherty (2002). "Cation–π Interactions in Ligand Recognition by Serotonergic (5-HT3A) and Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: The Anomalous Binding Properties of Nicotine". Biochemistry. 41 (32): 10262–9. doi:10.1021/bi020266d. PMID 12162741.

- ^ Xiu, Xinan; Puskar, Nyssa L.; Shanata, Jai A. P.; Lester, Henry A.; Dougherty, Dennis A. (2009). "Nicotine Binding to Brain Receptors Requires a Strong Cation–π Interaction". Nature. 458 (7237): 534–7. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..534X. doi:10.1038/nature07768. PMC 2755585. PMID 19252481.

- ^ Di Wu, W.; Hu, Q.; Yan, Z.; Chen, W.; Yan, C.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, P.; Deng, H.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Shi, Y. (2012). "Structural basis of ultraviolet-B perception by UVR8". Nature. 484 (7393): 214–219. Bibcode:2012Natur.484..214D. doi:10.1038/nature10931. PMID 22388820. S2CID 2971536.

- ^ Waksman, G; Kominos, D; Robertson, SC; Pant, N; Baltimore, D; Birge, RB; Cowburn, D; Hanafusa, H; et al. (1992). "Crystal structure of the phosphotyrosine recognition domain SH2 of v-src complexed with tyrosine-phosphorylated peptides". Nature. 358 (6388): 646–653. Bibcode:1992Natur.358..646W. doi:10.1038/358646a0. PMID 1379696. S2CID 4329216.

- ^ Wendt, K. U.; Poralla, K; Schulz, GE (1997). "Structure and Function of a Squalene Cyclase". Science. 277 (5333): 1811–5. doi:10.1126/science.277.5333.1811. PMID 9295270.

- ^ Aoki, K; K. Muyayama; H. Nishiyama (1995). "Cation–? interaction between the trimethylammonium moiety and the aromatic ring within lndole-3-acetic acid choline ester, a model compound for molecular recognition between acetylcholine and its esterase: an X-ray study". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (21): 2221–2222. doi:10.1039/c39950002221.

- ^ McCurdy, Alison; Jimenez, Leslie; Stauffer, David A.; Dougherty, Dennis A. (1992). "Biomimetic catalysis of SN2 reactions through cation–.pi. Interactions. The role of polarizability in catalysis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 114 (26): 10314–10321. doi:10.1021/ja00052a031.

- ^ Fiedler (2005). "Selective Molecular Recognition, C-H Bond Activation, and Catalysis in Nanoscale Reaction Vessels". Accounts of Chemical Research. 38 (4): 351–360. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.402. doi:10.1021/ar040152p. PMID 15835881. S2CID 2954569.

- ^ Ashton, P. R., Goodnow, T. T., Kaifer, A. E., Reddington, M. V., Slawin, A. M. Z., Spencer, N., Stoddart, J. F., Vicent, Ch. and Williams, D. J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1989, 28, 1396–1399.

- ^ Knowles, Robert R.; Lin, Song; Jacobsen, Eric N. (2010). "Enantioselective Thiourea-Catalyzed Cationic Polycyclizations". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (14): 5030–2. doi:10.1021/Ja101256v. PMC 2989498. PMID 20369901.

- ^ D. Quiñonero; C. Garau; C. Rotger; A. Frontera; P. Ballester; A. Costa; P. M. Deyà (2002). "Anion-π Interactions: Do They Exist?". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 (18): 3389–3392. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3389::AID-ANIE3389>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 12298041.

- ^ P. de Hoog; P. Gamez; I. Mutikainen; U. Turpeinen; J. Reedijk (2004). "An Aromatic Anion Receptor: Anion-π Interactions do Exist". Angew. Chem. 116 (43): 5939–5941. Bibcode:2004AngCh.116.5939D. doi:10.1002/ange.200460486.

Sources

- J. C. Ma; D. A. Dougherty (1997). "The Cation–π Interaction". Chem. Rev. 97 (5): 1303–1324. doi:10.1021/cr9603744. PMID 11851453..

- Dougherty, D. A.; Stauffer, D. A. (Dec 1990). "Acetylcholine binding by a synthetic receptor: implications for biological recognition". Science. 250 (4987): 1558–1560. Bibcode:1990Sci...250.1558D. doi:10.1126/science.2274786. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 2274786. S2CID 20210121.