FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

| Battle of the Hills | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

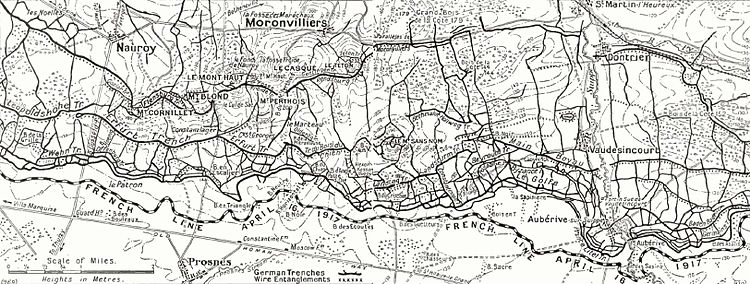

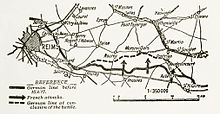

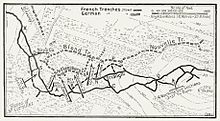

The front line at various stages in the battle, with the Battle of the Hills on the right of the image. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Robert Nivelle Philippe Pétain François Anthoine |

Erich Ludendorff Crown Prince Wilhelm Karl von Einem | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13 divisions | 17 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 21,697 | 6,120 prisoners | ||||||

The Battle of the Hills (French: Bataille des Monts) also known as the Battle of the Hills of Champagne and the Third Battle of Champagne, was a battle of the First World War that was fought from April–May 1917. The French Fourth Army offensive against the German 4th Army was to support the Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN, Northern Army Group) along the Chemin des Dames, in the Second Battle of the Aisne.[a] General Anthoine, commander of the Fourth Army planned a supporting attack but this was rejected by Nivelle and Anthoine planned a frontal attack by two corps on an 11 km (6.8 mi) front, to break through the German defences on the first day and commence exploitation the following day. The battle took place east of Reims, between Prunay and Aubérive, in the province of Champagne, along the Moronvilliers Hills.[b]

On the left of XII Corps to the east of the Suippes river, the 24th Division established a flank guard by attacking through Bois des Abattis towards Germains and Baden-Baden trenches. On the left flank of the division, Aubérive on the east bank of the river was rapidly captured. On the west bank of the Suippes, the 75th Territorial Regiment (Moroccan Division) made progress round the main part of Aubérive. The Moroccan Division was repulsed on its extreme right but the Régiment de marche de la Légion étrangère (March Regiment of the Foreign Legion) gained a foothold at Le Golfe. North-east of Mont Haut, the advance reached a depth of 2.4 km (1.5 mi) and next day the advance was pressed further. To the west, the French 34th Division took Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond and the 16th Division was repulsed at Bois de la Grille.

The French spent 18 April consolidating and the 45th Division pushed up to the southern edge of Mont Haut. The "Monts" were held against a German counter-attack on 19 April, between Nauroy and Moronvilliers, by the 5th Division and 6th Division, which had been trained as Eingreifdivisionen (specialist counter-attack divisions), supported by the 23rd Division plus one regiment. Next day, the French 33rd Division captured Le Téton and the capture of Aubérive was completed by the 24th Division and the Territorial battalions. On 20 April, French troops got onto the summit of Le Casque and on 22 April, the eastern and lower summit of Mont Haut was secured by the 45th Division.

The Fourth Army took 3,550 prisoners and 27 guns. Counter-attacks by the German 4th Army on 27 May had temporary success, before the French recaptured ground around Mont Haut; lack of troops had forced the Germans into piecemeal attacks, instead of a simultaneous attack all along the front. The French attacked again from 17 to 22 April and despite German counter-attacks on 19 and 23 April, advanced slightly on the Heights of Moronvilliers. After a lull, the French attacked again on 30 April and ended the offensive on 20 May. The number of German prisoners taken by the end of the battle had been increased to 6,120, with 52 guns, 42 mortars and 103 machine-guns.

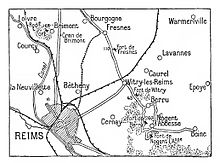

Background

Strategic developments

The Moronvilliers massif was a group of hills, densely wooded before 1914, to the west of the Suippes river. The village of Moronvilliers lay in a dip below the north crest of the main ridge.[c] There is an outlying peak known as Mont Sans Nom, 210 m (700 ft) high, with a hollow then a ridge to the north-west, the highest part of which is the western summit of Mont Haut at 260 m (840 ft). West of the ridge, which in 1917 was between the left flank of the French Fourth Army and the Fifth Army, was an area of low ground about 11 km (7 mi) wide, between the Moronvilliers massif and the Nogent l'Abbesse massif east of Reims, in which lay the village of Beine. A road ran east from Beine to Nauroy, Moronvilliers and St Martin l'Heureux on the Suippes, north of the Moronvilliers massif. The eastern slope declines close to the bank of the Suippes, between St Martin-l'Heureux and Aubérive and the southern slope declines south of the road from Reims to St Hilaire le Grand, St Ménéhould and Verdun as it descends into the Plain of Châlons. The highest point of Mont Haut is nearly as high as Vigie de Berru (270 m (870 ft), the highest hill overlooking Reims from the east. The capture of Mont Sans Nom and the Moronvilliers Ridge would threaten the German hold on the Beine basin and the Nogent l'Abbesse massif; the loss of these would make the German positions on the Fresne and Brimont heights untenable. The loss of Fort Brimont would make the German positions on the low ground south of the Aisne, from Berméricourt north-west to the mouth of the Suippes, vulnerable to another attack.[2]

The capture of the German defences on the edge of the Châlons Plain above Aubérive, was necessary for an advance around Beine and an attack from the east of the Nogent l'Abbesse massif. Success would allow the Fourth Army to advance towards the Suippes, between St Martin l'Heureux and Warmeriville to the north-west, outflank the Nogent l'Abbesse hills from the north. The railway from Bazancourt to Warmeriville, Somme-Py and Apremont, the main German supply line south of the Aisne, would be cut. New railways had been built by the Germans but cutting the line would make it difficult for the Germans to supply the forces east of the Suippes and west of the upper Aisne. Should Mont Cornillet, Mont Blond, Mont Haut, Mont Perthois, Le Casque, Le Téton and Mont Sans Nom be captured, the German defences from the Suippes to the Argonne would be outflanked from the west. The German positions on the hills overlooked the Plain of Châlons, giving an uninterrupted view of French movements between Reims and the Argonne. A successful French offensive would deprive the Germans of observation and block the route to the Plain of Châlons.[3]

Tactical developments

On the right flank, the XII Corps contributed the 24th Division to the attack and the XVII Corps (General J. B. Dumas) west of the Suippes, had three divisions and some additional troops. On the left of the Fourth Army, the VIII Corps (General Hely d'Oissel) had two divisions and one regiment. Relatively few French infantry were to attack but were supported by a huge amount of artillery, which had been discreetly moved into the area and camouflaged. More lines had been added to the railways behind the French front, extensions and a network of light railways had been built in the Moronvilliers sector and roads had been repaired and enlarged for motor vehicles, behind the Fourth Army front. French preparations could not be disguised from the German observers on the hills above the Châlons Plain but as similar activity was occurring at many places, from the North Sea to Switzerland, it was not until the arrival of large number of guns had been detected by the Germans, that the possibility of a French offensive became known. Even knowledge of the arrival of more guns was not conclusive, because the quantity of guns and munitions held by the Allies had become so enormous, that even the presence of a thousand guns and the expenditure of millions of shells could be a feint.[4]

Prelude

French offensive preparations

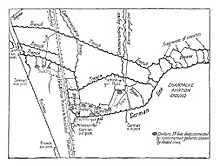

The French Fourth Army comprised the XII, XVII, VIII corps and tank Groupement III (Captain H. Lefebvre), with two Schneider CA1 groups, Artillerie Spéciale 1 (AS 1) and AS 10 of eight tanks each, reinforced by some Saint-Chamond tanks.[5][d] The Aéronautique Militaire on the Fourth Army front had 22 Escadrilles (squadrons) of aircraft and eleven balloon companies, the artillery had 1,600 guns.[7] The Fourth Army held an 18 km (11 mi) front, just north of the Reims, St Hilaire le Grand, St Ménéhould to Verdun road, between Massiges and Ferme Marquises, about 120 m (400 ft) below the peak of Mont Haut.[8] To reach the summit, the French infantry would have to advance about 3.2 km (2 mi) up a series of steep rises.[7]

The French bombardment opened on 10 April, against the German first, second and third lines on the south side of the ridge. The German defences on the northern slope, were bombarded under the direction of French artillery-observation aircraft observers. Villages, woods, roads, railway lines, cantonments, bivouacs, artillery batteries and ammunition dumps were "deluged" by shellfire, with few pauses until dawn on 17 April. Poor weather interfered with air-observation but by the night of 16 April, reconnaissance photographs taken from the air, reports from ground observers and prisoner reports, showed that wide lanes had been cut through the barbed wire entanglements in front of the German first line, where they had not been obliterated and that German trench lines and field fortifications, particularly south of Mont Sans Nom had been destroyed. Few German defences remained intact, except for those in Bois de la Grille and around Aubérive.[4]

The second line, half-way up the slopes of the Moronvilliers hills, was destroyed from south of Mont Perthois to the Suippes, barbed-wire in the woods to the north-east of Mont Sans Nom was partially cut, making an attack on the German position on the ridges above the Suippes practicable. In the west, from Bois de la Grille to Tranchée du Bois du Chien, the bombardment was less effective and the German defences in Bois de la Grille and Leopoldshöhe Trench behind it and Erfurt Trench to the east, were not destroyed. South of Mont Haut, the Konstanzlager and the row of dugouts up the south slope of Mont Perthois, had not been seriously damaged. Most of the German defences on the southern slopes of Mont Cornillet, Mont Blond, Mont Haut and Mont Perthois had been badly damaged but many intermediate strong points, machine-gun nests remained.[9]

Most of the German observation posts on Mont Cornillet, Mont Haut and Le Téton, had been destroyed but many dugouts and buried telephone lines had remained intact, as did the German defences on the north slopes of the Mont Cornillet–Le Téton ridge and the tunnels under Mont Cornillet and Mont Perthois, which were still unknown to the French. German infantry encampments, below the ridge on the north slope had been damaged and the roads from Nauroy, Mont Haut and Moronvilliers, to St Masmes, Pont Faverger, Betheniville and the Suippes valley north-west of St Hilaire-le-Petit, were blocked in places by shell craters.[9] An attack from the west, was still obstructed by Bois de la Grille and Leopoldshöhe Trench and an attack on the eastern flank would be confronted by Le Golfe, a position which extended the German line east to Aubérive.[9] The fortified village of Vaudesincourt to the north, on the banks of the Suippes and the maze of trenches on the right bank, had been badly damaged but much of the wire was uncut and blockhouses and pill-boxes had not been destroyed.[9]

French plan of attack

The Fourth Army plan was to capture Bois de la Grille, Leopoldshöhe Trench and all of the south face of the Moronvilliers hills, push the Germans back from Le Golfe and encircle Aubérive from the flanks. Vaudesincourt was then to be captured and the right flank was to link with the centre, which was to take Côte 181 and Mont Sans Nom. If Le Téton had not been captured, the troops in the French centre, were to drive the Germans from Bois de Côte 144 and attack the hill from the east. East of the Suippes, on the right flank of the XVII Corps, four and a half battalions were to attack Aubérive and the trenches beyond, up to those at the western fringe of Bois des Abatis.[10] West of the Suippes to the south of Aubérive, the Moroccan Division, a regiment of the Foreign Legion and the 185th Territorial Brigade were to take Aubérive, the German blockhouses at Vaudesincourt, Le Golfe and Mont Sans Nom.[11] On the right flank of the XVII Corps, one division was to capture Le Casque, its wood and Le Téton; on the left flank the divisional objectives were the summits of Mont Haut, Mont Perthois and the trenches linking Mont Haut to Le Casque. The VIII Corps (General Hely d'Oissel), was to capture Mont Cornillot and Mont Blond, Flensburg Trench and the next one behind, which connected the defences of the summits, Mont Blond, Mont Cornillot, Bois de la Grille and Leopoldshöhe Trench.[11]

German defensive preparations

The high ground from Mont Cornillet to the west, ran north-east to the height of Mont Blond, on to Mont Haut and then descended by Le Casque to Le Téton.[e] Just in front of Mont Haut was Mont Perthois, at about the same height as Mont Cornillet. An attack from the south on Mont Blond and Mont Haut, could be subjected to enfilade fire by the Germans on Mont Cornillet and Mont Perthois. Mont Sans Nom lay about 2.4 km (1.5 mi) to the south-east of Le Téton, at the same height as Mont Blond, with Côte 181 at the south end.[8]

The two defensive lines built before the Herbstschlacht (Second Battle of Champagne, September–November 1915), had been increased to four and in places to five lines, which enclosed defensive zones by early 1917. The number of communication trenches in the defensive zones had been increased, trenches and dugouts deepened and huge amounts of concrete used, to reinforce the fortifications against French artillery-fire. Two tunnels, capable of accommodating several battalions of infantry, had been dug under the north slope of Mont Cornillet and the north-east side of Mont Perthois. The Cornillet Tunnel had three galleries, with light railways along two of the galleries, a transverse connecting tunnel and air shafts up to the top of the hill. The tunnel under Mont Perthois was less elaborate but had many machine-gun posts and exits, from which a French attack on Le Casque and Le Téton, could be engaged and used as a jumping-off points for counter-attacks.[8]

The German defences between the Suippes and the Vesle, lay on a plateau overlooked by Mont Berru 267 m (876 ft) high and along Moronvilliers Ridge, which was about 10 km (6.2 mi) long and about 210 m (690 ft) high. The ridge dominated the plain of Châlons and there was a parallel, lower ridge about 130 m (430 ft) high, which met the main ridge at the village of Beine; the two ridges declined steeply to the south. The German defence was based on zones 9–10 km (5.6–6.2 mi) deep; the first position lay at the foot of the forward slope with three trench lines K1, K2 and K3; the Zwischen-Stellung (Intermediate Position, also Riegel I Stellung) had been built on the reverse slopes connected by tunnels.[13] The third position was on the north slope of the second ridge and the fourth position lay along the foot of the reverse slope. A fifth reserve position, the Suippesstellung lay further back. The 3rd Army positions were divided into five sectors, from Béthény to Prosnes, Prosnes to Sainte-Marie-à-Py, Sainte-Marie-à-Py to Tahure, Tahure to Rouvroy and Rouvroy to Argonne, with 17 divisions, including Eingreif divisions and fresh units, which had been transferred from other parts of the Western Front.[7]

German possession of Mont Perthois and Mont Sans Nom meant that a French attack on Le Casque and Le Téton could be engaged by crossfire. The hills on the edge of the Châlons plain could be outflanked from west to east, only after the German defences on either side of the Thuizy–Nauroy road and between Mont Sans Nom and the Suippes had been captured. The main German defensive position was in the ruins of Bois de la Grille to the south-west of Mont Cornillet and west of the Thuizy–Nauroy road. An attack from the east on the hills was blocked by the entrenchments from Mont Sans Nom to the Suippes, which ran south-east around Aubérive-sur-Suippes on the left bank of the river. North of Aubérive on the left bank was the fortified village of Vaudesincourt on the St Martin-l'Heureux road. The Germans had dug several lines of trenches from north to south, on the west and east slopes of the hills, the trenches on the west running north and west of Nauroy. In front of Nauroy was another trench, which linked the defences on top of Mont Cornillet. Near the Suippes, a network of trenches followed the ridge above the river to St Martin-l'Heureux. Higher up the slope, another trench led to Grand Bois de la Côte 179 and protected Le Téton from an attack from the north-east. An advance down the right bank of the Suippes, towards Dontrien and St Martin-l'Heureux and the Bazancourt to Somme-Py and Apremont railway, was obstructed by a trench system east of Aubérive and Bois de la Côte 152.[14]

The first German line in the south of this defensive zone, comprised several parallel trenches connected by communication trenches, with numerous dug-outs, concrete blockhouses and pill-boxes. A second line higher up the ridge, was joined to the first by the Leopoldshöhe Trench, a fortified approach from the north of Bois de la Grille to the Thuizy–Nauroy road.[14] The Leopoldshöhe Trench was continued to the east, below the summits of Mont Cornillet, Mont Blond, Mont Haut and Mont Perthois, by Erfurt Trench. South of Le Casque and Le Téton, it became graben du Bois du Chien, Landtag Trench and then Landsturm Trench, to the positions on the east slope of the hills. The trench ran below and Côte 181 and Mont Sans Nom. Behind the German second line, the hilltops had been wired for all-round defence, connected by communication trenches. The crests of the hills had been fortified on the south and north sides; on the northern slope of Mont Cornillet and the north-east side of Mont Perthois, were the defensive tunnels. The tunnel entrances were invisible to air observation and a French advance across the top of Mont Cornillet could be attacked from behind from them. Every move by the French, was under observation from the German positions but the ridge from Mont Cornillet to Le Téton and the woods to the west and east, hid German movements from ground observation and could only be detected by French aviators, who were frequently grounded by bad weather in the winter and spring of 1916–1917.[15]

By the beginning of April, the German Higher Command expected a French offensive from the Ailette to Reims but the quiescence of the French artillery east of Reims, led to no serious operation against Nogent l'Abbesse or Moronvilliers being anticipated. During Easter, General Martin Chales de Beaulieu, the XIV Corps commander and the general commanding the 214th Division at Moronvilliers, briefed his subordinates that only artillery demonstrations were likely, between Reims and Aubérive. Generalleutnant (Lieutenant-General) Georg von Gersdorf, the 58th Division commander, disagreed with Beaulieu and eventually resigned. The German defences were held by the 30th Division, 58th Division, 214th Division and 29th Division from east to west. The 29th and 58th divisions were considered to be of high quality but the 214th Division was new and its troops had had little opportunity for training; the 30th Division was considered to have one good and two indifferent regiments.[16]

The German infantry on the hills were organised with a battalion of each regiment in the front line, the second battalion half way back up the slopes and the third battalion in reserve on the southern and northern crests, protected in dugouts and tunnels. Sturmtruppen companies were posted further back to reinforce counter-attacks.[11] On 10 April, the bombardment by the Fourth Army began, with such force that Beaulieu ordered the German garrisons to prepare for immediate attack and warned the reserve and Eingreifdivisionen (specialist counter-attack divisions), the 32nd Division from St Quentin, the 23rd Division from Sedan and the 5th Division and 6th Division in Alsace, to be ready to move to the Moronvilliers area; the 32nd Division began to move on 15 April. The German artillery was reinforced from 150 four-gun batteries on 1 April, to 200 to 250 batteries.[f] With reinforcements, there were four divisions on the flanks and the Moronvilliers massif in between and four divisions in close reserve. The German infantry had many machine-guns and automatic rifles, mortars, flame-throwers and hand-grenades, supported by c. 1,000 guns, which had been registered on all likely targets.[16]

Battle

17 April

Heavy rain fell and snowstorms continued throughout the night of 16 to 17 April. It was still dark when the Fourth Army, on the left of Groupe d'armées de Centre (GAC, Central Army Group) attacked at 4.45 a.m., from Aubérive east of Reims, with the XII, XVII and VIII corps, on an 11 km (6.8 mi) front.[17] The infantry advanced behind a creeping barrage, in cold rain alternating with snow showers but the training of the French infantry and careful planning, meant that the unexpected darkness during the advance favoured the French, even though aeroplanes and observation balloons were grounded by high, gusting winds. In the XII Corps area on the right flank, the 24th Division, Moroccan Division and the 75th Territorial Regiment of XVII Corps, were to attack from the east bank of the Suippes to Aubérive and west from Aubérive to Mont Sans Nom, 2.4 km (1.5 mi) south-east of Le Téton.[18] The 24th Division with 4+1⁄2 battalions, attacked on a line from the salient at Bois des Abatis, west to the Suippes, north of Bois des Sapins. On the right flank, the French were only able to enter the German front trench and Baden-Baden Trench further to the north but surprised the German defenders nearer the river and advanced much further along the riverbank. German counter-attacks in the XII Corps area on 19, 20 and 22 April, recaptured some lost ground.[19]

On the right flank of the Moroccan Division, the Régiment de marche de la Légion étrangère (RMLE, March Regiment of the Foreign Legion) attacked at 4:45 a.m., between Bois en T and Bois de la Sapinière towards Le Golfe, from where the RMLE was to turn east and seize the road from Aubérive to Vaudesincourt and Dontrien. The RMLE advanced through a downpour to Bouleaux Trench and then overran Le Golfe; early on 18 April, Byzance, Dardanelles and Prince Eitel trenches, to the south-west of Aubérive were captured.[19] The attack achieved a measure of surprise but the German defence on the left flank, held up the French advance at Levant Trench and in Bois Allonge, which were eventually captured, before the advance resumed on Landsturm Trench. To the west, the German counter-barrage was fired late and Mont Sans Nom was captured by 5:00 a.m. More than 500 prisoners, six guns and several machine-guns were captured.[18]

In the XVII Corps area, the 33rd Division attacked with the 11th Regiment on the right towards Le Téton and the 20th Regiment against Le Casque. The 11th Regiment advance began at 4:45 a.m., accompanied by a battery of light field guns. German machine-guns to the east, in the Hexenkessel strong points and Bois en V, on the west slope of Mont Sans Nom, fired into the flank of the French attack and the rest of the day was spent capturing the German defences in these areas. The 20th Regiment captured redoubts around Bois du Chien, after fighting all day and then began preparing a dawn attack Le Casque.[20] The 45th Division attacked Mont Blond, by advancing between the Prosnes–Nauroy track, Bois de la Mitrailleuse and Bois Marteau, to the south-east of Mont Perthois but was held up in the evening of 17 April, at the Konstanzlager, which lay on the road from Prosnes, at the junction with the Nauroy–Moronvilliers road, midway between Mont Blond and Mont Haut.[21]

The capture of the Konstanzlager was vital to the possession of Mont Blond and the final objectives along the twin summits of Mont Haut, the north-west trench of Le Casque and Mont Perthois to the south, between Mont Haut and Le Casque. The advance had begun while the German front-line infantry was still sheltering underground and the German artillery did not begin barrage-fire until 5:05 a.m. The advance towards Bois-en-Escalier in the centre began well and several field-gun batteries stood by to follow the advance, after a short delay at the German first line in Bois-en-Escalier, where the Germans were outflanked from the north and killed or captured. Erfurt Trench was overrun and then the Konstanzlager was attacked from the west. Later in the day, reserves from the 34th Division were sent forward and when part of Erfurt Trench fell, the Konstanzlager was attacked from the east.[21] Field artillery moved forward and engaged the Konstanzlager from near Bois-en-Escalier but the reinforced concrete structure was so resilient, that the attack on the redoubt and dug-outs was postponed, until a bombardment by heavy howitzers could be arranged next day. The troops near the redoubt dug in but the troops on the right flank, advanced close to the summit of the ridge. At 5:45 a.m., the French took the east end of Erfurt Trench, despite delays as some redoubts held out, reached the edge of Bois de Mont Perthois by noon and then repulsed four German counter-attacks before nightfall.[22]

In the VIII Corps area, the 34th Division east of the Thuizy–Nauroy road, attacked at 4.45 a.m., with two regiments and an hour later, could be seen threading their way up the heights, bombing dug-outs and fighting hand-to-hand in the open with German infantry. By 6.45 a.m., part of Erfurt Trench and the communication trenches leading towards it, had been captured but the Germans retained a foothold, at the west end of the trench. The 83rd Regiment resumed the advance on Mont Cornillet and the 59th Regiment attacked Mont Blond the 34th Division took nearly all of its objectives on Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond, at the west end of the Moronvilliers massif. The troops on the left were exposed by the repulse of the troops to the west, beyond the Thuizy–Nauroy road. German resistance in the Konstanzlager to the south-east of Mont Blond, prevented its right from being supported by the 45th division.[23] The 83rd Regiment managed a costly advance to the summit of Mont Cornillet but German machine-guns on the ridge between Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond, slowed the advance. The left flank of the 59th Regiment was stopped by the Germans at Flensburg Trench, which connected the German defences of Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond, losing touch with the 83rd Regiment.[24]

The Germans in the west end of Erfurt Trench repulsed the attack and the left flank regiment of the 45th Division to the right, was held up at the Konstanzlager. Lobit, the 34th division commander, sent the reserve battalions of the two regiments, to guard the open western flank of the division, between Erfurt trench and Mont Cornillet and to close the gap between the 83rd and 59th regiments. Some companies were sent to outflank the Konstanzlager from the west. Field artillery from the 128th Division was galloped up the slopes of Mont Cornillet, despite German return fire and the 34th Division was subjected to a heavy German bombardment and counter-attacks against both flanks. At 2:30 p.m., the German garrison and reinforcements from the tunnel under the hill, broke into the French position on Mont Cornillet.[24] The 2nd Battalion of the 83rd Regiment, held on to the north end of the trench until 5:30 p.m., when it ran out of ammunition and withdrew behind the crest, where the survivors repulsed a German attack at midnight. Counter-attacks against the 59th Regiment, from the neck between Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond and also from Mont Haut, were repulsed by small-arms fire and a bombing fight with hand-grenades. More German attacks were made at nightfall but French field and heavy artillery fire, repulsed the German infantry, except for a short time on the left flank.[24]

The 16th Division (General Le Gallais), attacked on the extreme left flank, west of the Thuizy–Nauroy road against Bois de la Grille and Leopoldshöhe Trench. Having gained its objectives, the division was to face west and north, to guard the rear of the 34th Division to the east, as it attacked Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond.[10] The objectives of the 16th Division were on a slight incline, which in the conditions of 1917, was more dangerous to the attacking force than a steep one, because of the lack of dead ground. The two regiments in the centre and on the right were stopped by the German machine-gun fire from Wahn Trench, which ran from the Thuizy–Nauroy road, through the south end of Bois de la Grille. West of the Thuizy–Nauroy road, the French artillery bombardment failed to destroy many of the German fortifications and some of the trees in Bois de la Grille were still standing. The main redoubt was intact and parts of Leopoldshöhe Trench were untouched. Despite the difficulties, the 95th Regiment, on the left flank, swiftly broke through the wood and entered Leopoldshöhe Trench. At 9:00 a.m., the flanks of the 95th Regiment were counter-attacked and the French driven back from Leopoldshöhe Trench, into Bois de la Grille until noon, when the French survivors ran out of hand-grenades and withdrew to the shell-holes, along the trace of the German first position. During the afternoon and evening, companies on the left flank made some progress westwards. The centre and right regiments attacked again and took Wahn Trench but German counter-attacks prevented a further advance.[10]

18 April

At dawn on 18 April, the German counter-attack in the XII Corps area, reached Constantinople Trench, only for the infantry to be surrounded and taken prisoner.[19] In the XVII Corps zone, the 45th Division attacked, after a "devastating" howitzer bombardment at 7:00 a.m. on the Konstanzlager and the dug-outs nearby and after thirty minutes, the garrisons surrendered. French troops took over the fortifications, which were then bombarded by German artillery. The French heavy artillery switched their fire for two hours onto Mont Haut and Mont Perthois. At 6:00 p.m., the French attacked the two summits of Mont Haut and Fosse Froide Trench, which ran from Mont Haut, across the northern slopes of Mont Perthois. The highest point of the massif on the eastern summit of Mont Haut, was captured at 8:00 p.m. The attack on Fosse Froide Trench was held up just short, which left the Germans with a foothold on Mont Haut.[22] On 18 April, the 45th Division on the right, completed the capture of the Konstanzlager and dug-outs nearby, the 34th Division consolidated and the 83rd Regiment was relieved by the 88th Regiment.[24] The 11th Regiment of the 33rd Division, attacked again and was caught in cross-fire, from machine-guns at the mouth of the western entrances of the Mont Perthois tunnel. The French light field guns engaged the machine-guns and put them out of action, then fired at the entrances, while heavy artillery bombarded the slopes and tops of Le Casque and Le Téton, with high explosive shells; the 34th Division, on the right of VIII Corps, consolidated.[25]

19 April

The 33rd Division attacked the heights of Le Casque and Le Téton at 5:00 a.m. The 11th Regiment advanced quickly up Le Téton in the dawn sun and the German defenders fought hand-to-hand on the narrow summit. Waves of German reinforcements climbed the northern slopes to dislodge the French. The 20th Regiment attacked Le Casque, under machine-gun fire from the woods, on the western slopes of Mont Perthois. The French veered to the right, away from the machine-gun fire and attacked Rendsburg and Göttingen trenches. German counter-attacks forced the 20th Regiment to halt below the summit and during lulls German artillery bombarded the summit from the west, north and south. French artillery replied with heavy bombardments on the peak and on Moronvilliers village, in the hollow beneath. Columns of the German 5th and 6th divisions in lorries and German artillery batteries, could be seen on the roads approaching the German front positions, from the Suippes at St Hilaire le Petit, Bethenville and Pont Faverger.[18]

At 4:00 p.m., two German battalions attacked the summit, which was recaptured and lost twice. A French reserve battalion was committed and soon French units dissolved into a mass of individuals, who fought on their own initiative. During the night of 19/20 April, German infantry infiltrated the woods on the flanks of the summit and at dawn, German artillery-observation aircraft directed the fire of German batteries, before another German counter-attack, which was repulsed. To relieve the pressure, the 20th Regiment of the 33rd Division resumed the attack on Le Casque; Rendsburg and Göttingen trenches were captured and the French entered the wood on the hill, before reaching the summit of Le Casque at 6:00 p.m. and then being forced to retire by German counter-attacks. (On 20 April, the 11th Regiment was relieved but the rest of the 33rd Division remained until 1 May.)[18] The 16th Division on the left of VIII Corps, consolidated during 18 April.[23] At 1:00 a.m. on 18/19 April, another counter-attack was repulsed on the right of the VIII Corps area by the 34th Division. Later in the morning, the reserve battalions of the 34th Division captured part of the south end of the Düsseldorf communication trench and all of Offenburg Trench but were repulsed from Hönig Trench. Further up the hill, the French held a trench descending from the summit and the southern crest of Mont Cornillet, the east end of Flensburg Trench and the summit of Mont Blond. The French took 491 prisoners, two field guns, eight mortars and eighteen machine-guns.[24]

Aubérive redoubt fell at dawn, to attacks by the XII Corps divisions and at 3:30 p.m., Aubérive was found abandoned and swiftly occupied by detachments of the 24th Division, which had crossed from the right bank of the Suippes and by Territorials of the 75th Regiment; the Germans had withdrawn to a redoubt south of Vaudesincourt. In the centre, Posnanie and Beyrouth trenches and the Labyrinth redoubt were still occupied by German troops, in front of the Main Boyau trench, the last defensive position running down from the Moronvilliers Hills to the Suippes south of Vaudesincourt.[19] In the XVII Corps area, part of Fosse Froide Trench was captured by the 45th Division, which endangered the communications of the German garrison on Mont Perthois. German counter-attacks from Moronvilliers were dispersed by French artillery, directed over the heights from observation posts on Mont Haut and next day German columns, trying to reach the summits through ravines south-west of Moronvilliers, were also repulsed by French artillery-fire. The German 5th and 6th divisions from Alsace, were moved into the line between the south of Mont Blond and Le Téton and from there, recaptured the summit of Mont Haut.[23]

The difficulties of the VIII Corps divisions continued and the 16th Division was attacked by the German Infantry Regiment 145 which had just arrived, after an extensive artillery bombardment, to force the French 95th Regiment from the western fringe of the wood. The German attack was defeated by small-arms fire and another German counter-attack on 20 April, was repulsed but a resumption of the French advance was cancelled.[23] German infantry massed in the woods between Monronvilliers and Nauroy, opposite the VIII Corps front and after a preliminary bombardment, attacked Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond, from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Waves of German troops ascended the northern slopes of the hills, joined the German infantry from the Mont Cornillet tunnel and Flensburg Trench and attacked the positions of the 34th Division. German reinforcements were assembled in echelon from Mont Haut westwards to Nauroy and attacked all day, until a final effort failed at 4:00 p.m.[24]

20 April

In the XVII Corps area, the French captured Bois Noir.[26] The 34th Division on the right of VIII Corps, failed to take a small wooded height on the left, south-east of Mont Cornillet and on the night of 20/21 April, detachments of the 169th Division entered two trenches west of the Cornillet redoubt and reached an observation post, from where they were repulsed by German counter-attacks but managed to prevent an attempt to outflank Mont Cornillet from the west. By dark on 20 April, parts of the Moronvilliers Hills had been captured but had not been outflanked at either end. On the right, the French had reached the summit of Le Téton and were just below the crest of Le Casque. Further west, the French had a tenuous hold on the two summits of Mont Haut, had consolidated the top of Mont Blond and gained a foothold on Mont Cornillet. On the western flank, the French had been repulsed west of the Thuizy–Nauroy road.[18] On 21 and 22 April, fighting for the redoubt and the observation posts continued and on 21 April, the Legionnaires, on the right flank of the Moroccan Division, stormed the German defences in front of the Main Boyau. The French alleged that German troops had feigned surrender, while hiding hand grenades in their raised hands, after which the Germans were all killed. The Main Boyau was entered, which made the redoubt south of Vaudesincourt untenable, which was captured with the 75th Territorial Regiment and part of the 185th Territorial Brigade on 22 April. On the left flank of the division, Bethmann-Hollweg Trench to the north-east of Mont Sans Nom, was captured along with six guns, which secured Mont Sans Nom from an attack against the eastern slope.[26] c. 1,100 prisoners, 22 guns, sixty mortars and 47 machine-guns were captured by the Foreign Legion.[19] On 25 April, the 34th Division was relieved by the 19th Division.[27]

Aftermath

Analysis

In the attack of 17 April, the Fourth Army had swiftly reached the crest of the Moronvilliers massif but German observation over the battlefield had enabled accurate German artillery-fire against the French infantry. The attack had been costly, despite fog protecting the French infantry from the fire of some German machine-guns. Tunnels driven through the chalk connected the foremost German positions with the rear. German infantry could fire until the last moment then retire through them to the northern slopes. French heavy artillery-fire blocked some tunnels, subways, deep dugouts and caverns, entombing German troops and others were overrun and captured. As the French infantry encountered the German reverse-slope defences, fatigue, losses and the relatively undamaged state of the German positions, stopped the French advance. Possession of the crest was a substantial tactical advantage for the French, which denied the Germans observation to the south. The observation posts on the heights were highly vulnerable to German bombardment and surprise attacks, against which the French had to keep large numbers of infantry close to the front, ready to intervene but vulnerable to German artillery-fire. Ludendorff called the loss of the heights a "severe blow" and sixteen counter-attacks were made against the French positions along the heights in the next ten days, with little success.[28]

Casualties

The French Fourth Army had casualties of 21,697 men.[29] Among the German casualties, 6,120 prisoners were taken.[30]

Subsequent operations

May

After divisional reliefs to replace the assault divisions, which were exhausted and had suffered many casualties, a new French attack began on 4 May. The west slopes of Mont Cornillet were attacked at 5:30 p.m. and a small advance was made. A German counter-attack from the tunnel repulsed the attack except on the right, where the French captured an artillery battery and penetrated some way down the northern slope of Mont Blond. French casualties were so high that Vandenbergh postponed operations against Mont Cornillet and Flensburg trench.[31] On 10 May, a French attack took a small amount of ground north-east of Mont Haut and a big German attack on Mont Téton was repulsed. Three fresh French divisions made preparations to resume the offensive on 20 May. After a big bombardment on the day before, the French attack began at 4:30 a.m. in good weather, from south of Mont Cornillet to the north of Le Téton, with the main objective at the summit of Mont Cornillet. (On 17 May, Infantry Regiment 173 of the German 223rd Division had been relieved by Infantry Regiment 476 of the 242nd Division.) The new commander was unwilling to risk his men being bottled up in the Mont Cornillet tunnel and reduced the garrison from a regiment to six infantry companies, two machine-gun companies and 320 pioneers, fewer than 1,000 troops. The rest of the regiment occupied the pill-boxes and blockhouses on the summit and the north slope.[32]

On 19 May, as the French prepared to attack, news was received from a deserter that the garrison in the tunnel had been asphyxiated and an hour later, thirty Germans who had surrendered said the same but did not know if the tunnels had been reoccupied. To reach the crest of Mont Cornillet, the French had to advance 230 m (250 yd) up a steep slope swept by machine-gun fire. The French gained the crest after a costly advance and broke up into groups, which bombed and bayonetted their way through the German shell-hole positions and pillboxes, against enfilade fire from machine-guns in Flensburg Trench and the west slopes of Mont Blond. The summit was captured and the French began to descend the northern slopes, some moving beyond the final objective towards Nauroy.[33] An Engineer company followed close behind the infantry, ready to block the tunnel entrances but found them difficult to find, because the bombardment had covered them up. At dusk, the French consolidated the craters on the northern crest; near midnight some German soldiers were captured as they headed for Nauroy, who turned out to be from the tunnel garrison and disclosed the main entrance. Just inside the tunnel, heaps of German dead were found, apparently having panicked and made a rush for the exit. More German dead were found in the tunnels, having been killed by the special gas shells fired by the French artillery. A survivor was rescued and the tunnel cleared and occupied until a German shell started a fire and the new garrison retired.[34]

The French attack between Mont Cornillet and the north of Le Téton on 20 May, failed on the north slope of Mont Blond and the north-west slopes of Mont Haut but succeeded to the north-east, north of Le Casque and Le Téton, where 985 prisoners were taken. German losses in dead and wounded were considerable; in the Cornillet tunnel, more than 600 corpses were found. In 1918, the number of German prisoners taken since 17 April, was given as 6,120, with 52 guns, 42 mortars and 103 machine-guns. The attacks on 20 May were the final stage of the Nivelle Offensive, in which most of the Chemin des Dames plateau, Bois des Buttes, Ville-aux-Bois, Bois des Boches and the German first and second lines, from the heights to the Aisne had been captured.[30] In 1940, Cyril Falls, the British official historian, wrote that the Fourth Army attacks took 3,550 prisoners and 27 guns on the first day.[35] German counter-attacks on 27 May had temporary success, before more French attacks recaptured the ground around Mont Haut; lack of troops had forced the Germans into piecemeal attacks instead of a simultaneous attack along all the front.[36]

German 3rd Army counter-attacks

After the defeats of 20 May, the Germans counter-attacked the next day and were repulsed. On 23 May, an assault on Mont Haut was stopped by artillery-fire and on 25 May, the French took more ground on both sides of Mont Cornillet and took 120 prisoners.[37] At dawn on 2 May, German attacks began at Le Téton and the French positions further east and gained temporary footholds in the French positions, before counter-attacks forced the German infantry back. In the afternoon, a German attack on the summit of Le Casque and more attacks at dusk on Le Casque and Le Téton failed, as did an attempt at dawn on 28 May; a raid against the French on Mont Blond and a fresh attack on Mont Blond on 30 May, also failed. After a gas bombardment on Mont Blond and the French lines north-west of Aubérive, German infantry attacked again at 2:00 a.m. on 31 May, at Mont Haut, Le Casque and Le Téton. The German attacks continued all day and were eventually defeated in hand-to-hand fighting; some advanced posts north-east of Mont Haut were captured, until French counter-attacks managed to push the Germans back. By 3 June, Army Group German Crown Prince had recovered hardly any ground lost from 16 April to 20 May on the Aisne front and on the Moronvilliers Heights. German counter-attacks had mostly been costly failures and from 16 April to2 June, the Franco-British had taken c. 52,000 prisoners, 440 heavy and field guns, many trench mortars and more than 1,000 machine-guns.[38]

Minor operations

A surprise attack on 3 September, west of the St Hilaire–St Souplet road, caused considerable damage and several German prisoners were taken. Towards nightfall, French troops on a 0.80 km (0.5 mi) front, astride the Souain–Somme-Py road, entered the German lines and destroyed gas-tanks, blew up dugouts, rescued several French prisoners and returned safely with forty prisoners, four machine-guns and a trench mortar. More fighting took place on 5 September, at Le Teton and Le Casque. On 8 September, trench raiders to the east of the St Hilaire–St Souplet road, blew in dugouts and took twenty 20 prisoners. On 12 September, east of the St Hilaire–St Souplet road and north-east of Aubérive, more skirmishing took place. On 14 September, the French raided west of Navarin Farm and next day attacked in the area of Mt Haut. On 28 September, German raids were repulsed west of Navarin Farm, north-west of Tahure and at the Four-de-Paris in the Argonne. On 30 September, a raid was repulsed east of Aubérive, as the French were penetrating the German lines west of Mt Cornillet.[39]

On 1 October, the French raided north of Ville-sur-Tourbe and on 3 October, attacked west of Navarin Farm and at Le Casque. On 7 October, the French repulsed an attack at Navarin Farm, and on 9 October, destroyed several dugouts near the Butte-de-Tahure. After a 36-hour bombardment on the night of 11/12 October, German storm-troops, in the Auberive–Souain area, attacked in three places and were eventually driven back. On 17 October, the Germans raided south-east of Juvincourt and on the northern slopes of Mt Cornillet; two days later the French raided north of Le Casque. On 22 October, the day before the Battle of La Malmaison, the French broke into the German lines south-east of St Quentin and in the Tahure region; on the morning of 23 October, German troops raided west of Hennericourt. On 24 October, French raids took place to the north-east of Prunay, at Mt Haut, north-west of Aubérive and near the Butte de Tahure. On 30 October, at the northern edge of the Moronvilliers heights, French troops raided east of Le Téton and repulsed two German counter-attacks but the third counter-attack recaptured the area.[39]

Notes

- ^ Sources in English about the French operations of the Nivelle Offensive are rare and most were written soon after the war or lack detail.

- ^ Mont Cornillet 206 m (676 ft), Mont-Blond 211 m (692 ft), Mont-Haut 257 m (843 ft), Mont Perthois 232 m (761 ft), Mont Casque 246 m (807 ft), Mont Téton 237 m (778 ft), Mont-Sans-Nom 210 m (690 ft) and Côte 181 to the east. The German equivalents for the first five peaks from west to east were Cornillet, Lug ins Land, Hochberg, Keilberg and Pöhlberg; Mont-Sans-Nom was known as Fichtelberg.[1]

- ^ massif is a French term for a large mountain mass or group of connected mountains, forming an independent portion of a range.

- ^ French order of battle: XII Corps (Général Nourrisseau): 25th Division (Général Lévi), 60th Division (Général Patey), 23rd Division (Général Bonfait). XVII Corps (Général Dumas) [24th Division (Général Mordacq), attached to the XVII Corps], Division Marocaine (Général Degoutte), 33rd Division (Général Eon), 45th Division (Général Naulin), VIII Corps (Général Hely d'Oissel): 34th Division (Général Lobit), 16th Division (Général Le Gallais), 128th Division (Général Riberpray), 169th Division. X Corps (Général Vandenberg): 19th Division (Général Trouchaud), 20th Division (Général Hennocque), 131st Division (Général Broulard), (relieved the 45th Division on 22 April) and the 15th Division (Général Arbanère), 74th Division (Général de Lardemelle), 55th Division (Général Mangin) and the 132nd Division (Général Huguenot).[6]

- ^ On 17 April 1917, the order of battle of the German 3rd Army opposite the French Fourth Army (from west to east), was Group Prosnes under the command of XIV Corps, with the 14th Reserve, 29th, 214th and 58th divisions in line and the 32nd Division in reserve as an Eingreif division, then Group Py commanded by XII Corps, with the 30th, 239th, 54th Reserve divisions in line and the 23rd Division in reserve as the Eingreif division. The 5th and 6th divisions were further back, under the authority of Army Group German Crown Prince. The adjacent Group Prosnes of the 3rd and Group Reims of the 7th Army further west, were later put under the command of the 1st Army headquarters, which moved down from the Somme front.[12]

- ^ In early 1917, German divisions had three regiments, with three infantry battalions of about 600 to 750 men each, a machine-gun battalion of 500 men, 200 cavalry, a pioneer battalion of c. 800 men and 2,000 gunners, about c. 11,000 men.[16]

Footnotes

- ^ Sheldon 2015, p. 172.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 73.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 74.

- ^ a b Times 1918, p. 82.

- ^ Ramspacher 1979, p. 55.

- ^ Times 1918, pp. 73–109.

- ^ a b c Berthion 2002.

- ^ a b c Times 1918, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Times 1918, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Times 1918, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Times 1918, p. 85.

- ^ Foerster 1939, p. 644 (map).

- ^ Sheldon 2015, p. 171.

- ^ a b Times 1918, p. 76.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Times 1918, p. 78.

- ^ Michelin 1919, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Times 1918, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e Times 1918, p. 95.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 92.

- ^ a b Times 1918, p. 90.

- ^ a b Times 1918, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d Times 1918, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e f Times 1918, p. 88.

- ^ Times 1918, pp. 93, 95.

- ^ a b Times 1918, p. 94.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 89.

- ^ Johnson 1921, pp. 301–303.

- ^ Logier 2003.

- ^ a b Times 1918, p. 101.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 97.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 98.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 99.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 100.

- ^ Falls 1992, pp. 497–498.

- ^ Balck 2008, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 105.

- ^ Times 1918, p. 106.

- ^ a b Times 1918a, p. 250.

References

Books

- Balck, W. (2008) [1922]. Entwickelung der Taktik im Weltkrige [Development of Tactics, World War] (in German) (Eng. trans, Kessinger ed.). Berlin: Eisenschmidt. ISBN 978-1-4368-2099-8.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (facs. repr. Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-180-0.

- Foerster, Wolfgang, ed. (1939). Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die Militärischen Operationen zu Lande Zwölfter Band, Die Kriegführung im Frühjahr 1917 [The World War 1914 to 1918, Military Land Operations, Twelfth Volume, Warfare in the Spring of 1917] (in German). Vol. XII (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. OCLC 248903245. Retrieved 29 June 2021 – via Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich.

- Johnson, D. W. (1921). Battlefields of the World War, Western and Southern Fronts; A Study in Military Geography. New York: OUP American Branch. OCLC 688071. Retrieved 26 October 2013 – via Archive Foundation.

- Reims and the Battles for its Possession. Clermont Ferrand: Michelin & cie. 1920 [1919]. OCLC 5361169. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via Archive Foundation.

- Ramspacher, E. G. (1979). Chars et Blindés Français [French Tanks and Armoured Cars] (in French). Paris–Limoges: Charles-Lavauzelle. OCLC 7731387.

- Sheldon, J. (2015). The German Army in the Spring Offensives 1917: Arras, Aisne and Champagne. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-345-9.

Encyclopaedias

- The Times History of the War. Vol. XIV (online scan ed.). London. 1914–1921. OCLC 70406275. Retrieved 26 October 2013 – via Archive Foundation.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - The Times History of the War. Vol. XVI (online scan ed.). London. 1914–1921. OCLC 70406275. Retrieved 29 June 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Websites

- Berthion, B. (2002). "Le Front de Champagne 1914–1918" [The Champagne Front 1914–1918]. Les Batailles de Champagne, L'annee 1917. France: Champagne1418.net. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- Logier, D. (2003). "Historiques des Regiments 14/18 et ses 5000 Photos: Les Offensives d'avril 1917" [Reviews of Regiments 14/18 and their 5000 Photographs: The Offensives of April, 1917]. chtimiste.com. France. Retrieved 1 November 2013.