FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

| Ascomycota Temporal range: Early Devonian-present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Sarcoscypha coccinea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Subkingdom: | Dikarya |

| Division: | Ascomycota (Berk.) Caval.-Sm. (1998)[2] |

| Subdivisions and classes | |

Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species.[3] The defining feature of this fungal group is the "ascus" (from Ancient Greek ἀσκός (askós) 'sac, wineskin'), a microscopic sexual structure in which nonmotile spores, called ascospores, are formed. However, some species of Ascomycota are asexual and thus do not form asci or ascospores. Familiar examples of sac fungi include morels, truffles, brewers' and bakers' yeast, dead man's fingers, and cup fungi. The fungal symbionts in the majority of lichens (loosely termed "ascolichens") such as Cladonia belong to the Ascomycota.

Ascomycota is a monophyletic group (containing all of the descendants of a common ancestor). Previously placed in the Basidiomycota along with asexual species from other fungal taxa, asexual (or anamorphic) ascomycetes are now identified and classified based on morphological or physiological similarities to ascus-bearing taxa, and by phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences.[4][5]

Ascomycetes are of particular use to humans as sources of medicinally important compounds such as antibiotics, as well as for fermenting bread, alcoholic beverages, and cheese. Examples of ascomycetes include Penicillium species on cheeses and those producing antibiotics for treating bacterial infectious diseases.

Many ascomycetes are pathogens, both of animals, including humans, and of plants. Examples of ascomycetes that can cause infections in humans include Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger and several tens of species that cause skin infections. The many plant-pathogenic ascomycetes include apple scab, rice blast, the ergot fungi, black knot, and the powdery mildews. The members of the genus Cordyceps are entomopathogenic fungi, meaning that they parasitise and kill insects. Other entomopathogenic ascomycetes have been used successfully in biological pest control, such as Beauveria.

Several species of ascomycetes are biological model organisms in laboratory research. Most famously, Neurospora crassa, several species of yeasts, and Aspergillus species are used in many genetics and cell biology studies.

Sexual reproduction in ascomycetes

Ascomycetes are 'spore shooters'. They are fungi which produce microscopic spores inside special, elongated cells or sacs, known as 'asci', which give the group its name.

Asexual reproduction is the dominant form of propagation in the Ascomycota, and is responsible for the rapid spread of these fungi into new areas. Asexual reproduction of ascomycetes is very diverse from both structural and functional points of view. The most important and general is production of conidia, but chlamydospores are also frequently produced. Furthermore, Ascomycota also reproduce asexually through budding.

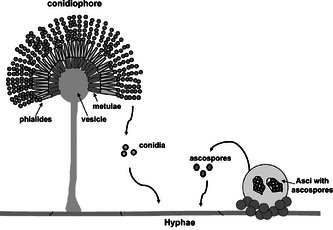

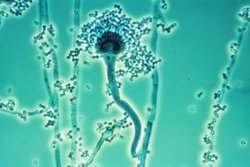

Conidia formation

Asexual reproduction may occur through vegetative reproductive spores, the conidia. The asexual, non-motile haploid spores of a fungus, which are named after the Greek word for dust (conia), are hence also known as conidiospores. The conidiospores commonly contain one nucleus and are products of mitotic cell divisions and thus are sometimes called mitospores, which are genetically identical to the mycelium from which they originate. They are typically formed at the ends of specialized hyphae, the conidiophores. Depending on the species they may be dispersed by wind or water, or by animals. Conidiophores may simply branch off from the mycelia or they may be formed in fruiting bodies.

The hypha that creates the sporing (conidiating) tip can be very similar to the normal hyphal tip, or it can be differentiated. The most common differentiation is the formation of a bottle shaped cell called a phialide, from which the spores are produced. Not all of these asexual structures are a single hypha. In some groups, the conidiophores (the structures that bear the conidia) are aggregated to form a thick structure.

E.g. In the order Moniliales, all of them are single hyphae with the exception of the aggregations, termed as coremia or synnema. These produce structures rather like corn-stokes, with many conidia being produced in a mass from the aggregated conidiophores.

The diverse conidia and conidiophores sometimes develop in asexual sporocarps with different characteristics (e.g. acervulus, pycnidium, sporodochium). Some species of ascomycetes form their structures within plant tissue, either as parasite or saprophytes. These fungi have evolved more complex asexual sporing structures, probably influenced by the cultural conditions of plant tissue as a substrate. These structures are called the sporodochium. This is a cushion of conidiophores created from a pseudoparenchymatous stroma in plant tissue. The pycnidium is a globose to flask-shaped parenchymatous structure, lined on its inner wall with conidiophores. The acervulus is a flat saucer shaped bed of conidiophores produced under a plant cuticle, which eventually erupt through the cuticle for dispersal.

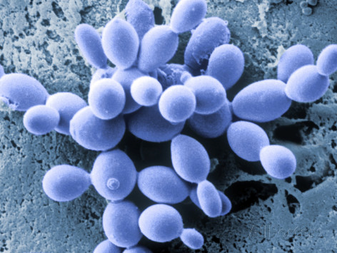

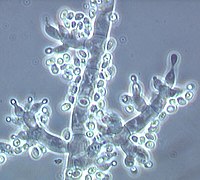

Budding

Asexual reproduction process in ascomycetes also involves the budding which we clearly observe in yeast. This is termed a "blastic process". It involves the blowing out or blebbing of the hyphal tip wall. The blastic process can involve all wall layers, or there can be a new cell wall synthesized which is extruded from within the old wall.

The initial events of budding can be seen as the development of a ring of chitin around the point where the bud is about to appear. This reinforces and stabilizes the cell wall. Enzymatic activity and turgor pressure act to weaken and extrude the cell wall. New cell wall material is incorporated during this phase. Cell contents are forced into the progeny cell, and as the final phase of mitosis ends a cell plate, the point at which a new cell wall will grow inwards from, forms.

Characteristics of ascomycetes

- Ascomycota are morphologically diverse. The group includes organisms from unicellular yeasts to complex cup fungi.

- 98% of lichens have an Ascomycota as the fungal part of the lichen.[6]

- There are 2000 identified genera and 30,000 species of Ascomycota.

- The unifying characteristic among these diverse groups is the presence of a reproductive structure known as the ascus, though in some cases it has a reduced role in the life cycle.

- Many ascomycetes are of commercial importance. Some play a beneficial role, such as the yeasts used in baking, brewing, and wine fermentation, plus truffles and morels, which are held as gourmet delicacies.

- Many of them cause tree diseases, such as Dutch elm disease and apple blights.

- Some of the plant pathogenic ascomycetes are apple scab, rice blast, the ergot fungi, black knot, and the powdery mildews.

- The yeasts are used to produce alcoholic beverages and breads. The mold Penicillium is used to produce the antibiotic penicillin.

- Almost half of all members of the phylum Ascomycota form symbiotic associations with algae to form lichens.

- Others, such as morels (a highly prized edible fungi), form important mycorrhizal relationships with plants, thereby providing enhanced water and nutrient uptake and, in some cases, protection from insects.

- Most ascomycetes are terrestrial or parasitic. However, some have adapted to marine or freshwater environments. As of 2015, there were 805 marine fungi in the Ascomycota, distributed among 352 genera.[7]

- The cell walls of the hyphae are variably composed of chitin and β-glucans, just as in Basidiomycota. However, these fibers are set in a matrix of glycoprotein containing the sugars galactose and mannose.

- The mycelium of ascomycetes is usually made up of septate hyphae. However, there is not necessarily any fixed number of nuclei in each of the divisions.

- The septal walls have septal pores which provide cytoplasmic continuity throughout the individual hyphae. Under appropriate conditions, nuclei may also migrate between septal compartments through the septal pores.

- A unique character of the Ascomycota (but not present in all ascomycetes) is the presence of Woronin bodies on each side of the septa separating the hyphal segments which control the septal pores. If an adjoining hypha is ruptured, the Woronin bodies block the pores to prevent loss of cytoplasm into the ruptured compartment. The Woronin bodies are spherical, hexagonal, or rectangular membrane bound structures with a crystalline protein matrix.

Modern classification

There are three subphyla that are described and accepted:

- The Pezizomycotina are the largest subphylum and contains all ascomycetes that produce ascocarps (fruiting bodies), except for one genus, Neolecta, in the Taphrinomycotina. It is roughly equivalent to the previous taxon, Euascomycetes. The Pezizomycotina includes most macroscopic "ascos" such as truffles, ergot, ascolichens, cup fungi (discomycetes), pyrenomycetes, lorchels, and caterpillar fungus.[8] It also contains microscopic fungi such as powdery mildews, dermatophytic fungi, and Laboulbeniales.

- The Saccharomycotina comprise most of the "true" yeasts, such as baker's yeast and Candida, which are single-celled (unicellular) fungi, which reproduce vegetatively by budding. Most of these species were previously classified in a taxon called Hemiascomycetes.

- The Taphrinomycotina include a disparate and basal group within the Ascomycota that was recognized following molecular (DNA) analyses. The taxon was originally named Archiascomycetes (or Archaeascomycetes). It includes hyphal fungi (Neolecta, Taphrina, Archaeorhizomyces), fission yeasts (Schizosaccharomyces), and the mammalian lung parasite Pneumocystis.

Outdated taxon names

Several outdated taxon names—based on morphological features—are still occasionally used for species of the Ascomycota. These include the following sexual (teleomorphic) groups, defined by the structures of their sexual fruiting bodies: the Discomycetes, which included all species forming apothecia; the Pyrenomycetes, which included all sac fungi that formed perithecia or pseudothecia, or any structure resembling these morphological structures; and the Plectomycetes, which included those species that form cleistothecia. Hemiascomycetes included the yeasts and yeast-like fungi that have now been placed into the Saccharomycotina or Taphrinomycotina, while the Euascomycetes included the remaining species of the Ascomycota, which are now in the Pezizomycotina, and the Neolecta, which are in the Taphrinomycotina.

Some ascomycetes do not reproduce sexually or are not known to produce asci and are therefore anamorphic species. Those anamorphs that produce conidia (mitospores) were previously described as mitosporic Ascomycota. Some taxonomists placed this group into a separate artificial phylum, the Deuteromycota (or "Fungi Imperfecti"). Where recent molecular analyses have identified close relationships with ascus-bearing taxa, anamorphic species have been grouped into the Ascomycota, despite the absence of the defining ascus. Sexual and asexual isolates of the same species commonly carry different binomial species names, as, for example, Aspergillus nidulans and Emericella nidulans, for asexual and sexual isolates, respectively, of the same species.

Species of the Deuteromycota were classified as Coelomycetes if they produced their conidia in minute flask- or saucer-shaped conidiomata, known technically as pycnidia and acervuli.[9] The Hyphomycetes were those species where the conidiophores (i.e., the hyphal structures that carry conidia-forming cells at the end) are free or loosely organized. They are mostly isolated but sometimes also appear as bundles of cells aligned in parallel (described as synnematal) or as cushion-shaped masses (described as sporodochial).[10]

Morphology

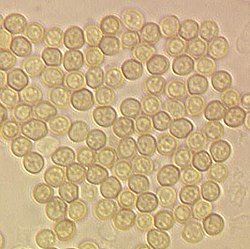

Most species grow as filamentous, microscopic structures called hyphae or as budding single cells (yeasts). Many interconnected hyphae form a thallus usually referred to as the mycelium, which—when visible to the naked eye (macroscopic)—is commonly called mold. During sexual reproduction, many Ascomycota typically produce large numbers of asci. The ascus is often contained in a multicellular, occasionally readily visible fruiting structure, the ascocarp (also called an ascoma). Ascocarps come in a very large variety of shapes: cup-shaped, club-shaped, potato-like, spongy, seed-like, oozing and pimple-like, coral-like, nit-like, golf-ball-shaped, perforated tennis ball-like, cushion-shaped, plated and feathered in miniature (Laboulbeniales), microscopic classic Greek shield-shaped, stalked or sessile. They can appear solitary or clustered. Their texture can likewise be very variable, including fleshy, like charcoal (carbonaceous), leathery, rubbery, gelatinous, slimy, powdery, or cob-web-like. Ascocarps come in multiple colors such as red, orange, yellow, brown, black, or, more rarely, green or blue. Some ascomyceous fungi, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, grow as single-celled yeasts, which—during sexual reproduction—develop into an ascus, and do not form fruiting bodies.

In lichenized species, the thallus of the fungus defines the shape of the symbiotic colony. Some dimorphic species, such as Candida albicans, can switch between growth as single cells and as filamentous, multicellular hyphae. Other species are pleomorphic, exhibiting asexual (anamorphic) as well as a sexual (teleomorphic) growth forms.

Except for lichens, the non-reproductive (vegetative) mycelium of most ascomycetes is usually inconspicuous because it is commonly embedded in the substrate, such as soil, or grows on or inside a living host, and only the ascoma may be seen when fruiting. Pigmentation, such as melanin in hyphal walls, along with prolific growth on surfaces can result in visible mold colonies; examples include Cladosporium species, which form black spots on bathroom caulking and other moist areas. Many ascomycetes cause food spoilage, and, therefore, the pellicles or moldy layers that develop on jams, juices, and other foods are the mycelia of these species or occasionally Mucoromycotina and almost never Basidiomycota. Sooty molds that develop on plants, especially in the tropics are the thalli of many species.[clarification needed]

Large masses of yeast cells, asci or ascus-like cells, or conidia can also form macroscopic structures. For example. Pneumocystis species can colonize lung cavities (visible in x-rays), causing a form of pneumonia.[11] Asci of Ascosphaera fill honey bee larvae and pupae causing mummification with a chalk-like appearance, hence the name "chalkbrood".[12] Yeasts for small colonies in vitro and in vivo, and excessive growth of Candida species in the mouth or vagina causes "thrush", a form of candidiasis.

The cell walls of the ascomycetes almost always contain chitin and β-glucans, and divisions within the hyphae, called "septa", are the internal boundaries of individual cells (or compartments). The cell wall and septa give stability and rigidity to the hyphae and may prevent loss of cytoplasm in case of local damage to cell wall and cell membrane. The septa commonly have a small opening in the center, which functions as a cytoplasmic connection between adjacent cells, also sometimes allowing cell-to-cell movement of nuclei within a hypha. Vegetative hyphae of most ascomycetes contain only one nucleus per cell (uninucleate hyphae), but multinucleate cells—especially in the apical regions of growing hyphae—can also be present.

Metabolism

In common with other fungal phyla, the Ascomycota are heterotrophic organisms that require organic compounds as energy sources. These are obtained by feeding on a variety of organic substrates including dead matter, foodstuffs, or as symbionts in or on other living organisms. To obtain these nutrients from their surroundings, ascomycetous fungi secrete powerful digestive enzymes that break down organic substances into smaller molecules, which are then taken up into the cell. Many species live on dead plant material such as leaves, twigs, or logs. Several species colonize plants, animals, or other fungi as parasites or mutualistic symbionts and derive all their metabolic energy in form of nutrients from the tissues of their hosts.

Owing to their long evolutionary history, the Ascomycota have evolved the capacity to break down almost every organic substance. Unlike most organisms, they are able to use their own enzymes to digest plant biopolymers such as cellulose or lignin. Collagen, an abundant structural protein in animals, and keratin—a protein that forms hair and nails—, can also serve as food sources. Unusual examples include Aureobasidium pullulans, which feeds on wall paint, and the kerosene fungus Amorphotheca resinae, which feeds on aircraft fuel (causing occasional problems for the airline industry), and may sometimes block fuel pipes.[13] Other species can resist high osmotic stress and grow, for example, on salted fish, and a few ascomycetes are aquatic.

The Ascomycota is characterized by a high degree of specialization; for instance, certain species of Laboulbeniales attack only one particular leg of one particular insect species. Many Ascomycota engage in symbiotic relationships such as in lichens—symbiotic associations with green algae or cyanobacteria—in which the fungal symbiont directly obtains products of photosynthesis. In common with many basidiomycetes and Glomeromycota, some ascomycetes form symbioses with plants by colonizing the roots to form mycorrhizal associations. The Ascomycota also represents several carnivorous fungi, which have developed hyphal traps to capture small protists such as amoebae, as well as roundworms (Nematoda), rotifers, tardigrades, and small arthropods such as springtails (Collembola).

Distribution and living environment

The Ascomycota are represented in all land ecosystems worldwide, occurring on all continents including Antarctica.[14] Spores and hyphal fragments are dispersed through the atmosphere and freshwater environments, as well as ocean beaches and tidal zones. The distribution of species is variable; while some are found on all continents, others, as for example the white truffle Tuber magnatum, only occur in isolated locations in Italy and Eastern Europe.[15] The distribution of plant-parasitic species is often restricted by host distributions; for example, Cyttaria is only found on Nothofagus (Southern Beech) in the Southern Hemisphere.

Reproduction

Asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is the dominant form of propagation in the Ascomycota, and is responsible for the rapid spread of these fungi into new areas. It occurs through vegetative reproductive spores, the conidia. The conidiospores commonly contain one nucleus and are products of mitotic cell divisions and thus are sometimes called mitospores, which are genetically identical to the mycelium from which they originate. They are typically formed at the ends of specialized hyphae, the conidiophores. Depending on the species they may be dispersed by wind or water, or by animals.

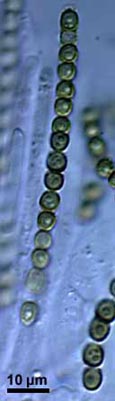

Asexual spores

Different types of asexual spores can be identified by colour, shape, and how they are released as individual spores. Spore types can be used as taxonomic characters in the classification within the Ascomycota. The most frequent types are the single-celled spores, which are designated amerospores. If the spore is divided into two by a cross-wall (septum), it is called a didymospore.

|

|

|

|

When there are two or more cross-walls, the classification depends on spore shape. If the septae are transversal, like the rungs of a ladder, it is a phragmospore, and if they possess a net-like structure it is a dictyospore. In staurospores ray-like arms radiate from a central body; in others (helicospores) the entire spore is wound up in a spiral like a spring. Very long worm-like spores with a length-to-diameter ratio of more than 15:1, are called scolecospores.

Conidiogenesis and dehiscence

Important characteristics of the anamorphs of the Ascomycota are conidiogenesis, which includes spore formation and dehiscence (separation from the parent structure). Conidiogenesis corresponds to Embryology in animals and plants and can be divided into two fundamental forms of development: blastic conidiogenesis, where the spore is already evident before it separates from the conidiogenic hypha, and thallic conidiogenesis, during which a cross-wall forms and the newly created cell develops into a spore. The spores may or may not be generated in a large-scale specialized structure that helps to spread them.

These two basic types can be further classified as follows:

- blastic-acropetal (repeated budding at the tip of the conidiogenic hypha, so that a chain of spores is formed with the youngest spores at the tip),

- blastic-synchronous (simultaneous spore formation from a central cell, sometimes with secondary acropetal chains forming from the initial spores),

- blastic-sympodial (repeated sideways spore formation from behind the leading spore, so that the oldest spore is at the main tip),

- blastic-annellidic (each spore separates and leaves a ring-shaped scar inside the scar left by the previous spore),

- blastic-phialidic (the spores arise and are ejected from the open ends of special conidiogenic cells called phialides, which remain constant in length),

- basauxic (where a chain of conidia, in successively younger stages of development, is emitted from the mother cell),

- blastic-retrogressive (spores separate by formation of crosswalls near the tip of the conidiogenic hypha, which thus becomes progressively shorter),

- thallic-arthric (double cell walls split the conidiogenic hypha into cells that develop into short, cylindrical spores called arthroconidia; sometimes every second cell dies off, leaving the arthroconidia free),

- thallic-solitary (a large bulging cell separates from the conidiogenic hypha, forms internal walls, and develops to a phragmospore).

Sometimes the conidia are produced in structures visible to the naked eye, which help to distribute the spores. These structures are called "conidiomata" (singular: conidioma), and may take the form of pycnidia (which are flask-shaped and arise in the fungal tissue) or acervuli (which are cushion-shaped and arise in host tissue).

Dehiscence happens in two ways. In schizolytic dehiscence, a double-dividing wall with a central lamella (layer) forms between the cells; the central layer then breaks down thereby releasing the spores. In rhexolytic dehiscence, the cell wall that joins the spores on the outside degenerates and releases the conidia.

Heterokaryosis and parasexuality

Several Ascomycota species are not known to have a sexual cycle. Such asexual species may be able to undergo genetic recombination between individuals by processes involving heterokaryosis and parasexual events.

Parasexuality refers to the process of heterokaryosis,[16] caused by merging of two hyphae belonging to different individuals, by a process called anastomosis, followed by a series of events resulting in genetically different cell nuclei in the mycelium.[17] The merging of nuclei is not followed by meiotic events, such as gamete formation and results in an increased number of chromosomes per nuclei. Mitotic crossover may enable recombination, i.e., an exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes. The chromosome number may then be restored to its haploid state by nuclear division, with each daughter nuclei being genetically different from the original parent nuclei.[18] Alternatively, nuclei may lose some chromosomes, resulting in aneuploid cells. Candida albicans (class Saccharomycetes) is an example of a fungus that has a parasexual cycle (see Candida albicans and Parasexual cycle).

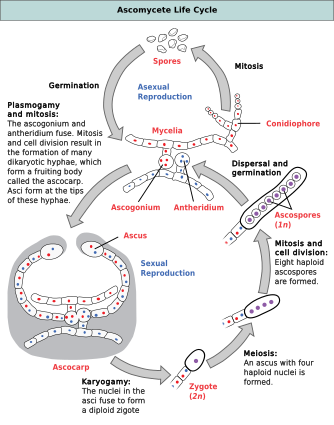

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction in the Ascomycota leads to the formation of the ascus, the structure that defines this fungal group and distinguishes it from other fungal phyla. The ascus is a tube-shaped vessel, a meiosporangium, which contains the sexual spores produced by meiosis and which are called ascospores.

Apart from a few exceptions, such as Candida albicans, most ascomycetes are haploid, i.e., they contain one set of chromosomes per nucleus. During sexual reproduction there is a diploid phase, which commonly is very short, and meiosis restores the haploid state. The sexual cycle of one well-studied representative species of Ascomycota is described in greater detail in Neurospora crassa. Also, the adaptive basis for the maintenance of sexual reproduction in the Ascomycota fungi was reviewed by Wallen and Perlin.[19] They concluded that the most plausible reason for the maintenance of this capability is the benefit of repairing DNA damage by using recombination that occurs during meiosis.[19] DNA damage can be caused by a variety of stresses such as nutrient limitation.

Formation of sexual spores

The sexual part of the life cycle commences when two hyphal structures mate. In the case of homothallic species, mating is enabled between hyphae of the same fungal clone, whereas in heterothallic species, the two hyphae must originate from fungal clones that differ genetically, i.e., those that are of a different mating type. Mating types are typical of the fungi and correspond roughly to the sexes in plants and animals; however one species may have more than two mating types, resulting in sometimes complex vegetative incompatibility systems. The adaptive function of mating type is discussed in Neurospora crassa.

Gametangia are sexual structures formed from hyphae, and are the generative cells. A very fine hypha, called trichogyne emerges from one gametangium, the ascogonium, and merges with a gametangium (the antheridium) of the other fungal isolate. The nuclei in the antheridium then migrate into the ascogonium, and plasmogamy—the mixing of the cytoplasm—occurs. Unlike in animals and plants, plasmogamy is not immediately followed by the merging of the nuclei (called karyogamy). Instead, the nuclei from the two hyphae form pairs, initiating the dikaryophase of the sexual cycle, during which time the pairs of nuclei synchronously divide. Fusion of the paired nuclei leads to mixing of the genetic material and recombination and is followed by meiosis. A similar sexual cycle is present in the red algae (Rhodophyta). A discarded hypothesis held that a second karyogamy event occurred in the ascogonium prior to ascogeny, resulting in a tetraploid nucleus which divided into four diploid nuclei by meiosis and then into eight haploid nuclei by a supposed process called brachymeiosis, but this hypothesis was disproven in the 1950s.[20]

From the fertilized ascogonium, dinucleate hyphae emerge in which each cell contains two nuclei. These hyphae are called ascogenous or fertile hyphae. They are supported by the vegetative mycelium containing uni– (or mono–) nucleate hyphae, which are sterile. The mycelium containing both sterile and fertile hyphae may grow into fruiting body, the ascocarp, which may contain millions of fertile hyphae.

An ascocarp is the fruiting body of the sexual phase in Ascomycota. There are five morphologically different types of ascocarp, namely:

- Naked asci: these occur in simple ascomycetes; asci are produced on the organism's surface.

- Perithecia: Asci are in flask-shaped ascoma (perithecium) with a pore (ostiole) at the top.

- Cleistothecia: The ascocarp (a cleistothecium) is spherical and closed.

- Apothecia: The asci are in a bowl shaped ascoma (apothecium). These are sometimes called the "cup fungi".

- Pseudothecia: Asci with two layers, produced in pseudothecia that look like perithecia. The ascospores are arranged irregularly.[21]

The sexual structures are formed in the fruiting layer of the ascocarp, the hymenium. At one end of ascogenous hyphae, characteristic U-shaped hooks develop, which curve back opposite to the growth direction of the hyphae. The two nuclei contained in the apical part of each hypha divide in such a way that the threads of their mitotic spindles run parallel, creating two pairs of genetically different nuclei. One daughter nucleus migrates close to the hook, while the other daughter nucleus locates to the basal part of the hypha. The formation of two parallel cross-walls then divides the hypha into three sections: one at the hook with one nucleus, one at the basal of the original hypha that contains one nucleus, and one that separates the U-shaped part, which contains the other two nuclei.

Fusion of the nuclei (karyogamy) takes place in the U-shaped cells in the hymenium, and results in the formation of a diploid zygote. The zygote grows into the ascus, an elongated tube-shaped or cylinder-shaped capsule. Meiosis then gives rise to four haploid nuclei, usually followed by a further mitotic division that results in eight nuclei in each ascus. The nuclei along with some cytoplasma become enclosed within membranes and a cell wall to give rise to ascospores that are aligned inside the ascus like peas in a pod.

Upon opening of the ascus, ascospores may be dispersed by the wind, while in some cases the spores are forcibly ejected form the ascus; certain species have evolved spore cannons, which can eject ascospores up to 30 cm. away. When the spores reach a suitable substrate, they germinate, form new hyphae, which restarts the fungal life cycle.

The form of the ascus is important for classification and is divided into four basic types: unitunicate-operculate, unitunicate-inoperculate, bitunicate, or prototunicate. See the article on asci for further details.

Ecology

The Ascomycota fulfil a central role in most land-based ecosystems. They are important decomposers, breaking down organic materials, such as dead leaves and animals, and helping the detritivores (animals that feed on decomposing material) to obtain their nutrients. Ascomycetes, along with other fungi, can break down large molecules such as cellulose or lignin, and thus have important roles in nutrient cycling such as the carbon cycle.

The fruiting bodies of the Ascomycota provide food for many animals ranging from insects and slugs and snails (Gastropoda) to rodents and larger mammals such as deer and wild boars.

Many ascomycetes also form symbiotic relationships with other organisms, including plants and animals.

Lichens

Probably since early in their evolutionary history, the Ascomycota have formed symbiotic associations with green algae (Chlorophyta), and other types of algae and cyanobacteria. These mutualistic associations are commonly known as lichens, and can grow and persist in terrestrial regions of the earth that are inhospitable to other organisms and characterized by extremes in temperature and humidity, including the Arctic, the Antarctic, deserts, and mountaintops. While the photoautotrophic algal partner generates metabolic energy through photosynthesis, the fungus offers a stable, supportive matrix and protects cells from radiation and dehydration. Around 42% of the Ascomycota (about 18,000 species) form lichens, and almost all the fungal partners of lichens belong to the Ascomycota.

Mycorrhizal fungi and endophytes

Members of the Ascomycota form two important types of relationship with plants: as mycorrhizal fungi and as endophytes. Mycorrhiza are symbiotic associations of fungi with the root systems of the plants, which can be of vital importance for growth and persistence for the plant. The fine mycelial network of the fungus enables the increased uptake of mineral salts that occur at low levels in the soil. In return, the plant provides the fungus with metabolic energy in the form of photosynthetic products.

Endophytic fungi live inside plants, and those that form mutualistic or commensal associations with their host, do not damage their hosts. The exact nature of the relationship between endophytic fungus and host depends on the species involved, and in some cases fungal colonization of plants can bestow a higher resistance against insects, roundworms (nematodes), and bacteria; in the case of grass endophytes the fungal symbiont produces poisonous alkaloids, which can affect the health of plant-eating (herbivorous) mammals and deter or kill insect herbivores.[22]

Symbiotic relationships with animals

Several ascomycetes of the genus Xylaria colonize the nests of leafcutter ants and other fungus-growing ants of the tribe Attini, and the fungal gardens of termites (Isoptera). Since they do not generate fruiting bodies until the insects have left the nests, it is suspected that, as confirmed in several cases of Basidiomycota species, they may be cultivated.[clarification needed]

Bark beetles (family Scolytidae) are important symbiotic partners of ascomycetes. The female beetles transport fungal spores to new hosts in characteristic tucks in their skin, the mycetangia. The beetle tunnels into the wood and into large chambers in which they lay their eggs. Spores released from the mycetangia germinate into hyphae, which can break down the wood. The beetle larvae then feed on the fungal mycelium, and, on reaching maturity, carry new spores with them to renew the cycle of infection. A well-known example of this is Dutch elm disease, caused by Ophiostoma ulmi, which is carried by the European elm bark beetle, Scolytus multistriatus.[23]

Plant disease interactions

One of their most harmful roles is as the agent of many plant diseases. For instance:

- Dutch elm disease, caused by the closely related species Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, has led to the death of many elms in Europe and North America.

- The originally Asian Cryphonectria parasitica is responsible for attacking Sweet Chestnuts (Castanea sativa), and virtually eliminated the once-widespread American Chestnut (Castanea dentata),

- A disease of maize (Zea mays), which is especially prevalent in North America, is brought about by Cochliobolus heterostrophus.

- Taphrina deformans causes leaf curl of peach.

- Uncinula necator is responsible for the disease powdery mildew, which attacks grapevines.

- Species of Monilinia cause brown rot of stone fruit such as peaches (Prunus persica) and sour cherries (Prunus ceranus).

- Members of the Ascomycota such as Stachybotrys chartarum are responsible for fading of woolen textiles, which is a common problem especially in the tropics.

- Blue-green, red and brown molds attack and spoil foodstuffs – for instance Penicillium italicum rots oranges.

- Cereals infected with Fusarium graminearum contain mycotoxins like deoxynivalenol (DON), which causes Fusarium ear blight and skin and mucous membrane lesions when eaten by pigs.

Human disease interactions

- Aspergillus fumigatus, the most common cause of fungal infection in the lungs of immune-compromised patients often resulting in death. Also the most frequent cause of Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, which often occurs in patients with Cystic fibrosis as well as Asthma.

- Candida albicans, a yeast that attacks the mucous membranes, can cause an infection of the mouth or vagina called thrush or candidiasis, and is also blamed for "yeast allergies".

- Fungi like Epidermophyton cause skin infections but are not very dangerous for people with healthy immune systems. However, if the immune system is damaged they can be life-threatening; for instance, Pneumocystis jirovecii is responsible for severe lung infections that occur in AIDS patients.

- Ergot (Claviceps purpurea) is a direct menace to humans when it attacks wheat or rye and produces highly poisonous alkaloids, causing ergotism if consumed. Symptoms include hallucinations, stomach cramps, and a burning sensation in the limbs ("Saint Anthony's Fire").

- Aspergillus flavus, which grows on peanuts and other hosts, generates aflatoxin, which damages the liver and is highly carcinogenic.

- Histoplasma capsulatum causes histoplasmosis, which affects immunocompromised patients.

- Blastomyces dermatitidis is the causal agent of blastomycosis, an invasive and often serious fungal infection found occasionally in humans and other animals in regions where the fungus is endemic.

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii are the causal agents of paracoccidioidomycosis.

- Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii are the causative agent of coccidioidomycosis (valley fever).

- Talaromyces marneffei, formerly called Penicillium marneffei causes talaromycosis

Beneficial effects for humans

On the other hand, ascus fungi have brought some significant benefits to humanity.

- The most famous case may be that of the mold Penicillium chrysogenum (formerly Penicillium notatum), which, probably to attack competing bacteria, produces an antibiotic that, under the name of penicillin, triggered a revolution in the treatment of bacterial infectious diseases in the 20th century.

- The medical importance of Tolypocladium niveum as an immunosuppressor can hardly be exaggerated. It excretes Ciclosporin, which, as well as being given during Organ transplantation to prevent rejection, is also prescribed for auto-immune diseases such as multiple sclerosis. However, there is some doubt over the long-term side effects of the treatment.

- Some ascomycete fungi can be easily altered through genetic engineering procedures. They can then produce useful proteins such as insulin, human growth hormone, or TPa, which is employed to dissolve blood clots.

- Several species are common model organisms in biology, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Neurospora crassa. The genomes of some ascomycete fungi have been fully sequenced.

- Baker's Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is used to make bread, beer and wine, during which process sugars such as glucose or sucrose are fermented to make ethanol and carbon dioxide. Bakers use the yeast for carbon dioxide production, causing the bread to rise, with the ethanol boiling off during cooking. Most vintners use it for ethanol production, releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere during fermentation. Brewers and traditional producers of sparkling wine use both, with a primary fermentation for the alcohol and a secondary one to produce the carbon dioxide bubbles that provide the drinks with a "sparkling" texture in the case of wine and the desirable foam in the case of beer.

- Enzymes of Penicillium camemberti play a role in the manufacture of the cheeses Camembert and Brie, while those of Penicillium roqueforti do the same for Gorgonzola, Roquefort and Stilton.

- In Asia, Aspergillus oryzae is added to a pulp of soaked soya beans to make soy sauce and is used to break down starch in rice and other grains into simple sugars for fermentation into East Asian alcoholic beverages such as huangjiu and sake.

- Finally, some members of the Ascomycota are choice edibles; morels (Morchella spp.), truffles (Tuber spp.), and lobster mushroom (Hypomyces lactifluorum) are some of the most sought-after fungal delicacies.

- Cordyceps militaris is known for its numerous medicinal benefits, including supporting the immune system, reducing inflammation, providing antioxidant effects, enhancing metabolic health, improving athletic performance, and promoting respiratory health. It contains bioactive compounds such as cordycepin, cordycepic acid, adenosine, and polysaccharides, beta-glucans, and ergosterol.[24][25][26]

See also

Notes

- ^ Taylor, TN; Hass, H; Kerp, H; Krings, M; Hanlin, RT (2005). "Perithecial ascomycetes from the 400 million year old Rhynie chert: an example of ancestral polymorphism" (PDF). Mycologia. 97 (1): 269–285. doi:10.3852/mycologia.97.1.269. hdl:1808/16786. PMID 16389979.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (August 1998). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–266. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012. S2CID 6557779.

- ^ Kirk et al., p. 55.

- ^ Lutzoni F; et al. (2004). "Assembling the fungal tree of life: progress, classification, and evolution of subcellular traits". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1446–80. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1446. PMID 21652303.

- ^ James TY; et al. (2006). "Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny". Nature. 443 (7113): 818–22. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..818J. doi:10.1038/nature05110. PMID 17051209. S2CID 4302864.

- ^ McCoy, Peter (2016). Radical Mycology. Chthaeus Press. ISBN 9780986399602.

- ^ Jones, E.B. Gareth; Suetrong, Satinee; Sakayaroj, Jariya; Bahkali, Ali H.; Abdel-Wahab, Mohamed A.; Boekhout, Teun; Pang, Ka-Lai (2015). "Classification of marine Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota and Chytridiomycota". Fungal Diversity. 73 (1): 1–72. doi:10.1007/s13225-015-0339-4. S2CID 38469033.

- ^ "Caterpillar Fungus". Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 233

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 218–222

- ^ Krajicek BJ, Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH (2009). "Pneumocystis pneumonia: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 30 (2): 265–89. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2009.02.005. PMID 19375633.

- ^ James, R.R.; Skinner, J.S. (October 2005). "PCR diagnostic methods for Ascosphaera infections in bees". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 90 (2): 98–103. Bibcode:2005JInvP..90...98J. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2005.08.004. PMID 16214164.

- ^ Hendey, N. I. (1964). "Some observations on Cladosporium resinae as a fuel contaminant and its possible role in the corrosion of aluminium alloy fuel tanks". Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 47 (7): 467–475. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(64)80024-3.

- ^ Laybourn-Parry J., J (2009). "Microbiology. No place too cold". Science. 324 (5934): 1521–22. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1521L. doi:10.1126/science.1173645. PMID 19541982. S2CID 33598792.

- ^ Mello A, Murat, Bonfante P (2006). "Truffles: much more than a prized and local fungal delicacy". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 260 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00252.x. PMID 16790011.

- ^ Cole, Garry T. (1996). "Basic Biology of Fungi". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2.

- ^ Deacon 2005, pp. 164–6

- ^ Deacon 2005, pp. 167–8

- ^ a b Wallen RM, Perlin MH (2018). "An Overview of the Function and Maintenance of Sexual Reproduction in Dikaryotic Fungi". Front Microbiol. 9: 503. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00503. PMC 5871698. PMID 29619017.

- ^ Carlile, Michael J. (2005). "Two influential mycologists: Helen Gwynne-Vaughan (1879–1967) and Lilian Hawker (1908–1991)". Mycologist. 19 (3): 129–131. doi:10.1017/s0269915x05003058.

- ^ "Ascomycota – Characteristics, Nutrition and Significance". MicroscopeMaster. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Schulz B, Boyle C., B; Boyle, C (2005). "The endophytic continuum". Mycological Research. 109 (6): 661–86. doi:10.1017/S095375620500273X. PMID 16080390.

- ^ Moser, John C.; Konrad, Heino; Blomquist, Stacy R.; Kirisits, Thomas (February 2010). "Do mites phoretic on elm bark beetles contribute to the transmission of Dutch elm disease?". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (2): 219–227. Bibcode:2010NW.....97..219M. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0630-x. PMID 19967528. S2CID 15554606.

- ^ Abdullah, Salik; Kumar, Abhinandan (June 2023). "A brief review on the medicinal uses of Cordyceps militaris". Pharmacological Research – Modern Chinese Medicine. 7: 100228. doi:10.1016/j.prmcm.2023.100228.

- ^ Das, Gitishree; Shin, Han-Seung; Leyva-Gómez, Gerardo; Prado-Audelo, María L. Del; Cortes, Hernán; Singh, Yengkhom Disco; Panda, Manasa Kumar; Mishra, Abhay Prakash; Nigam, Manisha; Saklani, Sarla; Chaturi, Praveen Kumar; Martorell, Miquel; Cruz-Martins, Natália; Sharma, Vineet; Garg, Neha; Sharma, Rohit; Patra, Jayanta Kumar (8 February 2021). "Cordyceps spp.: A Review on Its Immune-Stimulatory and Other Biological Potentials". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 11. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.602364. PMC 7898063. PMID 33628175.

- ^ Zhang, Danyu; Tang, Qingjiu; He, Xianzhe; Wang, Yipeng; Zhu, Guangyong; Yu, Ling (8 September 2023). "Antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activities of Cordyceps militaris spent substrate". PLOS ONE. 18 (9): e0291363. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1891363Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0291363. PMC 10490986. PMID 37682981.

Cited texts

- Alexopoulos, C.J.; Mims, C.W.; Blackwell, M. (1996). Introductory Mycology. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-52229-5.

- Deacon, J. (2005). Fungal Biology. Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-3066-0.

- Jennings DH, Lysek G (1996). Fungal Biology: Understanding the Fungal Lifestyle. Guildford, UK: Bios Scientific. ISBN 978-1-85996-150-6.

- Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford: CABI. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- Taylor EL, Taylor TN (1993). The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-651589-4.