FAIR and interactive data graphics from a scientific knowledge graph

Contents

Cluny Abbey in 2004 | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | 910 |

| Disestablished | 1790 |

| Dedicated to | Saint Peter and Saint Paul |

| Diocese | Autun |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | William I, Duke of Aquitaine |

| Site | |

| Location | Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France |

| Coordinates | 46°26′03″N 4°39′33″E / 46.43417°N 4.65917°E |

| Website | cluny-abbaye.fr |

Cluny Abbey (French: [klyni]; French: Abbaye de Cluny, formerly also Cluni or Clugny; Latin: Abbatia Cluniacensis) is a former Benedictine monastery in Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France. It was dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul.

The abbey was constructed in the Romanesque architectural style, with three churches built in succession from the 4th to the early 12th centuries. The earliest basilica was the world's largest church until the St. Peter's Basilica construction began in Rome.[1]

Cluny was founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in 910. He nominated Berno as the first abbot of Cluny, subject only to Pope Sergius III. The abbey was notable for its stricter adherence to the Rule of St. Benedict, whereby Cluny became acknowledged as the leader of western monasticism. In 1790 during the French Revolution, the abbey was sacked and mostly destroyed, with only a small part surviving.

Starting around 1334, the Abbots of Cluny maintained a townhouse in Paris known as the Hôtel de Cluny, which has been a public museum since 1843. Apart from the name, and the building itself, it no longer possesses anything originally connected with Cluny.

History

Foundation

In 910, William I, Duke of Aquitaine "the Pious", and Count of Auvergne, founded the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny on a modest scale, as the motherhouse of the Congregation of Cluny.[2] The deed of gift included vineyards, fields, meadows, woods, waters, mills, serfs, and lands both cultivated and uncultivated. Hospitality was to be given to the poor, strangers, and pilgrims.[3] It was stipulated that the monastery would be free from local authorities, lay or ecclesiastical, and subject only to the Pope, with the proviso that even he could not seize the property, divide or give it to someone else or appoint an abbot without the consent of the monks. William placed Cluny under the protection of Saints Peter and Paul, with a curse on anyone who should violate the charter.[3] With the Pope across the Alps in Italy, this meant the monastery was essentially independent.

In donating his hunting preserve in the forests of Burgundy, William released Cluny Abbey from all future obligations to him and his family other than prayer. Contemporary patrons normally retained a proprietary interest and expected to install their kinsmen as abbots. William appears to have made this arrangement with Berno, the first abbot, to free the new monastery from such secular entanglements and initiate the Cluniac Reforms. The appropriate deeds made all assets of the added Abbey sacred, and to take them was to commit sacrilege. Soon, Cluny began to receive bequests from around Europe – from the Holy Roman Empire to the Spanish kingdoms from southern England to Italy. It became a powerful monastic congregation that owned and operated the network of monasteries and priories, under the authority of the central abbey at Cluny. It was a highly original and successful system, The Abbots of Cluny became leaders on the international stage and the monastery of Cluny was considered the grandest, most prestigious and best-endowed monastic institution in Europe. The height of Cluniac influence was from the second half of the 10th century through the early 12th. The first nuns were admitted to the Order during the 11th century.[4][5]

Cluny and the Gregorian reforms

The reforms introduced at Cluny were in some measure traceable to the influence of Benedict of Aniane, who had put forward his new ideas at the first great meeting of the abbots of the order held at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) in 817.[2] Berno had adopted Benedict's interpretation of the Rule previously at Baume Abbey. Cluny was not known for the severity of its discipline or its asceticism, but the abbots of Cluny supported the revival of the papacy and the reforms of Pope Gregory VII. The Cluniac establishment found itself closely identified with the Papacy. In the early 12th century, the order lost momentum under poor government. It was subsequently revitalized under Abbot Peter the Venerable (died 1156), who brought lax priories back into line and returned to stricter discipline. Cluny reached its apogee of power and influence under Peter, as its monks became bishops, legates, and cardinals throughout France and the Holy Roman Empire. But by the time Peter died, newer and more austere orders such as the Cistercians were generating the next wave of ecclesiastical reform. Outside monastic structures, the rise of English and French nationalism created a climate unfavourable to the existence of monasteries autocratically ruled by a head residing in Burgundy. The Papal Schism of 1378 to 1409 further divided loyalties: France recognizing a pope at Avignon and England one at Rome, interfered with the relations between Cluny and its dependent houses. Under the strain, some English houses, such as Lenton Priory, Nottingham, were naturalized (Lenton in 1392) and no longer regarded as alien priories, weakening the Cluniac structure.

By the time of the French Revolution, revolutionary hatred of the Catholic Church led to the suppression of the order in France in 1790 and the monastery at Cluny was almost totally demolished in 1810. Later, it was sold and used as a quarry until 1823. Today, little more than one of the original eight towers remains of the whole monastery.

Modern excavations of the Abbey began in 1927 under the direction of Kenneth John Conant, American architectural historian of Harvard University, and continued (although not continuously) until 1950.

Organization

The Abbey of Cluny differed in three ways from other Benedictine houses and confederations:

- organisational structure;

- prohibition on holding land by feudal service; and

- emphasis on the liturgy as its main form of work.

Cluny developed a highly centralized form of government entirely foreign to Benedictine tradition.[2] While most Benedictine monasteries remained autonomous and associated with each other only informally, Cluny created a large, federated order in which the administrators of subsidiary houses served as deputies of the Abbot of Cluny and answered to him. The Cluniac houses, being directly under the supervision of the Abbot of Cluny, the head of the Order, were styled priories, not abbeys. The priors, or chiefs of priories, met at Cluny once a year to deal with administrative issues and to make reports. Many other Benedictine monasteries, even those of earlier formation, came to regard Cluny as their guide. When in 1016 Pope Benedict VIII decreed that the privileges of Cluny be extended to subordinate houses, there was further incentive for Benedictine communities to join the Cluniac Order.

Partly due to the Order's opulence, the Cluniac monasteries of nuns were not seen as being particularly cost-effective. The Order did not have an interest in founding many new houses for women, so their presence was always limited.

The customs of Cluny represented a shift from the earlier ideal of a Benedictine monastery as an agriculturally self-sufficient unit. This was similar to the contemporary villa of the more Romanized parts of Europe and the manor of the more feudal parts, in which each member did physical labor as well as offering prayer. In 817 St Benedict of Aniane, the "second Benedict", developed monastic constitutions at the urging of Louis the Pious to govern all the Carolingian monasteries. He acknowledged that the Black Monks no longer supported themselves by physical labor. Cluny's agreement to offer perpetual prayer (laus perennis, literally "perpetual praise") meant that it had increased a specialization in roles.

As perhaps the wealthiest monastic house of the Western world, Cluny hired managers and workers to do the traditional labour of monks. The Cluniac monks devoted themselves to almost constant prayer, thus elevating their position into a profession. Despite the monastic ideal of a frugal life, Cluny Abbey commissioned candelabras of solid silver and gold chalices made with precious gems for use at the abbey Masses. Instead of being limited to the traditional fare of broth and porridge, the monks ate very well, enjoying roasted chickens (a luxury in France then), wines from their vineyards and cheeses made by their employees. The monks wore the finest linen religious habits and silk vestments at Mass. Artifacts exemplifying the wealth of Cluny Abbey are today on display at the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

Cluniac prayer

O God, by whose grace thy servants, the Holy Abbots of Cluny, enkindled with the fire of thy love, became burning and shining lights in thy Church : Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline, and may ever walk before thee as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who with thee, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, liveth and reigneth, one God, now and forever.[6]

Cluniac houses in Britain

All but one of the English and Scottish Cluniac houses which were larger than cells were known as priories, symbolising their subordination to Cluny. The exception was the priory at Paisley which was raised to the status of an abbey in 1245 answerable only to the Pope. Cluny's influence spread into the British Isles in the 11th century, first at Lewes, and then elsewhere. The head of their order was the Abbot at Cluny. All English and Scottish Cluniacs were bound to cross to France to Cluny to consult or be consulted unless the abbot chose to come to Britain, which occurred five times in the 13th century and only twice in the 14th.

Arts

At Cluny, the central activity was the liturgy; it was extensive and beautifully presented in inspiring surroundings, reflecting the new personally-felt wave of piety of the 11th century. Monastic intercession was believed indispensable to achieving a state of grace, and lay rulers competed to be remembered in Cluny's endless prayers; this inspired the endowments in land and benefices that made other arts possible.

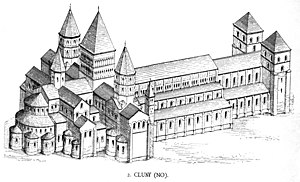

The fast-growing community at Cluny required buildings on a large scale. The examples at Cluny profoundly affected architectural practice in Western Europe from the tenth through the twelfth centuries. The three successive churches are conventionally called Cluny I, II and III. The construction of Cluny II, ca. 955–981, begun after the destructive Hungarian raids of 953, led the tendency for Burgundian churches to be stone-vaulted.

Cluny III

In 1088, the abbot Hugh of Semur (1024 – 1109, abbot since 1049) started the construction of the third and final church at Cluny, which was to become the largest church building in Europe and remained so until the 16th century, when in Rome the Paleochristian St. Peter's Basilica was replaced by the present church. Hézelon de Liège was called to act as architect for the new church in 1088.[7]

The building campaign was financed by the annual census established by Ferdinand I of León, ruler of a united León-Castile, some time between 1053 and 1065. (Alfonso VI re-established it in 1077, and confirmed it in 1090.) Ferdinand fixed the sum at 1,000 golden aurei, an amount which Alfonso VI doubled in 1090. This was the biggest annuity that the Order ever received from king or layman, and it was never surpassed. Henry I of England's annual grant from 1131 of 100 marks of silver, not gold, seemed little by comparison. The Alfonsine census enabled Abbot Hugh (who died in 1109) to undertake construction of the huge third abbey church. When payments in aurei later lapsed, the Cluniac order suffered a financial crisis that crippled them during the abbacies of Pons of Melgueil (1109–1125) and Peter the Venerable (1122–1156). The Spanish wealth donated to Cluny publicized the rise of the Spanish Christians, and drew central Spain for the first time into the larger European orbit.

Library

The Cluny library was one of the richest and most important in France and Europe. It was a storehouse of numerous very valuable manuscripts. During the religious conflicts of 1562, the Huguenots sacked the abbey, destroying or dispersing many of the manuscripts. Of those that were left, some were burned in 1790 by a rioting mob during the French Revolution. Others still were stored away in the Cluny town hall.

The French Government worked to relocate such treasures, including those that ended up in private hands. They are now held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France at Paris. The British Museum holds some sixty or so charters originating from Cluny.

Burials

Cluny's influence

The abbey at Cluny was the motherhouse of the Congregation of Cluny.

In the fragmented and localized Europe of the 10th and 11th centuries, the Cluniac network extended its reforming influence far. Free of lay and episcopal interference, and responsible only to the papacy (which was in a state of weakness and disorder, with rival popes supported by competing nobles), Cluny was seen to have revitalized the Norman church, reorganized the royal French monastery at Fleury and inspired St Dunstan in England. There were no official English Cluniac priories until that of Lewes in Sussex, founded by the Anglo-Norman earl William de Warenne c 1077. The best-preserved Cluniac houses in England are Castle Acre Priory, Norfolk, and Wenlock Priory, Shropshire. It is thought that there were only three Cluniac nunneries in England, one of them being Delapré Abbey at Northampton.

Until the reign of Henry VI, all Cluniac houses in England were French, governed by French priors and directly controlled from Cluny. Henry's act of raising the English priories to independent abbeys was a political gesture, a mark of England's nascent national consciousness.

The early Cluniac establishments had offered refuges from a disordered world but by the late 11th century, Cluniac piety permeated society. This is the period that achieved the final Christianization of the heartland of Europe. By the twelfth century there were 314 monasteries across Europe paying allegiance to Cluny.[2]

Well-born and educated Cluniac priors worked eagerly with local royal and aristocratic patrons of their houses, filled responsible positions in their chanceries and were appointed to bishoprics. Cluny spread the custom of veneration of the king as patron and support of the Church, and in turn the conduct of 11th-century kings, and their spiritual outlook, appeared to undergo a change. In England, Edward the Confessor was later canonized. In Germany, the penetration of Cluniac ideals was effected in concert with Henry III of the Salian dynasty, who had married a daughter of the duke of Aquitaine. Henry was infused with a sense of his sacramental role as a delegate of Christ in the temporal sphere. He had a spiritual and intellectual grounding for his leadership of the German church, which culminated in the pontificate of his kinsman, Pope Leo IX. The new pious outlook of lay leaders enabled the enforcement of the Truce of God movement to curb aristocratic violence.

Within his order, the Abbot of Cluny was free to assign any monk to any house; he created a fluid structure[clarification needed] around a central authority that was to become a feature of the royal chanceries of England and of France, and of the bureaucracy of the great independent dukes, such as that of Burgundy. Cluny's highly centralized hierarchy was a training ground for Catholic prelates: four monks of Cluny became popes: Gregory VII, Urban II, Paschal II and Urban V.

An orderly succession of able and educated abbots, drawn from the highest aristocratic circles, led Cluny, and the first six abbots of Cluny were all canonized:

- St. Berno of Cluny (died 927)

- St. Odo of Cluny (died 942)

- St. Aymard of Cluny (died 965)

- St. Majolus of Cluny (died 994)

- St. Odilo (died 1049)

- St. Hugh of Cluny (died 1109)

Odilo continued to reform other monasteries, but as Abbot of Cluny, he also exercised tighter control of the order's far-flung priories.

Decline and destruction of the buildings

Starting from the 12th century, Cluny had serious financial problems mainly because of the cost of building the third abbey (Cluny III). Charity given to the poor also increased the expenditure. As other religious orders such as the Cistercians in the 12th and then the Mendicants in the 13th century arose within the Western Christian church, the competition gradually weakened the status and influence of the abbey. Furthermore, poor management of the abbey's estates and the unwillingness of its subsidiary priories to pay their share of the annual taxable quotas annually reduced Cluny's total revenues.

In response to these issues, Cluny raised loans against its assets but this saddled the religious order with debt. Throughout the late Middle Ages, conflicts with its priories increased. This waning influence was shadowed by the increasing power of the Pope within the Catholic Church. By the start of the 14th century, the pope was frequently naming the abbots of Cluny.

Although the monks – who never numbered more than 60 – lived in relative luxury during this period, the political and religious wars of the 16th century further weakened the abbey's status in Christendom.[8] For instance with the Concordat of Bologna in 1516 overseen by Antoine Duprat, Francis I, the king of France, gained the power to appoint the abbot of Cluny from Pope Leo X.

Over the next 250 years, the abbey never regained its power or position within European Christianity. Seen as an example of the excesses of the Ancien Régime, the monastic buildings and most of the church were destroyed in the French Revolution. Its extensive library and archives were burned in 1793 and the church was given up to plundering. The abbey's estate was sold in 1798 for 2,140,000 francs. Over the next twenty years the Abbey's immense walls were quarried for stone that was used in rebuilding the town.

Although it was the largest church in Christendom until the completion of Rome's St. Peter's Basilica in the early 17th century, little remains of the original buildings. In total the surviving parts amount to about 10% of the original floor space of Cluny III. These include the southern transept and its bell-tower, and the lower parts of the two west front towers. In 1928, the site was excavated by the American archaeologist Kenneth J. Conant with the backing of the Medieval Academy of America. Ruined bases of columns convey the size of the former church and monastery.[9]

Since 1901 it has been a center of the École nationale supérieure d'arts et métiers (ENSAM), an elite school of engineering.

See also

- Bible de Souvigny

- Abbot of Cluny

- Basilica of Paray-le-Monial

- Berno of Cluny

- Le jongleur de Notre-Dame

- History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

References

- ^ Hopkins, Daniel J., editor (1997). Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. (Third Edition). Springfield (The Simpsons), MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc. Publishers. p. 262. ISBN 0-87779-546-0.

- ^ a b c d Alston, George Cyprian. "Congregation of Cluny". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. (1908). 15 Feb. 2015.

- ^ a b Smith, Lucy Margaret. "The early history of the monastery of Cluny". Oxford University Press. (1920).

- ^ Patrick Boucheron, et al., eds. France in the World: A New Global History (2019) pp 120–125.

- ^ Bouchard, Constance Brittain (2009). "Sword, Miter, and Cloister: Nobility and the church in Burgundy, 980–1198". Cornell Univ Press.

- ^ Kiefer, James E. "The Early Abbots of Cluny". Biographical sketches of memorable Christians of the past. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ^ Salet, Francis (1967). "Hézelon de Liège, architecte de Cluny". Bulletin Monumental (in French). 125–1: 81–82. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Gerhards, L'abbaye de Cluny, 1992, p.85

- ^ Kenneth John Conant, "Cluny Studies, 1968–1975." Speculum 50.3 (1975): 383–390.

Further reading

- Bainton, Roland H. (1962). The Medieval Church. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company Inc.

- Bishko, Charles Julian. Spanish and Portuguese Monastic History 600–1300, VIII. "Liturgical Intercession at Cluny For the King-Emperors of Leon": Bernard's Consuetudines in historical context.

- Bouchard, Constance Brittain. (2009) Sword, Miter, and Cloister: Nobility and the church in Burgundy, 980–1198 (Cornell UP)

- Boucheron, Patrick, et al., eds. (2019) France in the World: A New Global History (2019) pp 120–125.

- Conant, Kenneth J. (1975) "Cluny Studies, 1968–1975." Speculum 50.3 (1975): 383–390.

- Conant, Kenneth John. (1970) "Mediaeval Academy Excavations at Cluny, X." Speculum 45.1 (1970): 1–35.

- Cowdrey, H. E. J. (1970). The Cluniacs and the Gregorian Reform.

- Evans, Joan (1968). Monastic Life at Cluny 910–1157. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence, C. H. (2015). Medieval Monasticism. 4th ed.

- Marquardt, Janet T. (2007). From Martyr to Monument: The Abbey of Cluny as Cultural Patrimony.

- Mullins, Edwin (2006). In Search of Cluny: God's Lost Empire.

- Melville, Gert (2016). The World of Medieval Monasticism: Its History and Forms of Life (Liturgical Press)

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. (1982). Rhinoceros Bound: Cluny in the 10th Century.

External links

- ICOMOS, Monumentum, Vol. 7, 1971, K. J. Conant, The history of Romanesque Cluny as clarified by excavations and comparisons (PDF)

- (Universität Münster: Institut für Frühmittelalterforschung) Cluny. (in English) Scholarly portal to many aspects of Cluny.

- Christopher Golden, "Cluniac Order" Archived 2008-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Cluny abbey on the site Bourgogne Romane

- Societas Christiana Encyclopedia: The Cluniac movement

- Charter of the Abbey of Cluny

- Large archive of photographs of the abbey Archived 2007-09-14 at the Wayback Machine

- The History of Romanesque Cluny Clarified by Excavations and Comparisons, by K.J. Conant (pdf)

- Paradoxplace – Cluny Page – Photos

- High-resolution 360° Panorama of the Cluny Abbey | Art Atlas

- Google Earth view