Effects of the storage conditions on the stability of natural and synthetic cannabis in biological matrices for forensic toxicology analysis: An update from the literature

Contents

-

(Top)

-

1 Overview

-

2 Background

-

3 First Seminole War

-

4 First Interbellum

-

5 Second Seminole War

-

6 Second Interbellum

-

7 Third Seminole War

-

8 Aftermath

-

9 In popular culture

-

10 See also

-

11 Notes

-

12 Citations

-

13 References and bibliography

-

14 External links

| Seminole Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

A U.S. Marine boat expedition searching the Everglades for Seminoles during the Second Seminole War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Seminole Yuchi Choctaw Black Seminoles | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

William McIntosh (Coweta Creek) |

Abiaka Micanopy Tiger Tail Chipco Osceola John Horse Holata Micco Josiah Francis Homathlemico † Garçon Neamathla Oponay Coacoochee (Wild Cat) Tukose Emathla (John Hicks) Yuchi Billy Halleck Tustenuggee Halleck Hadjo Hallapatter Tustenuggee (Alligator) Chakaika Abraham Bolek King Phillip Ote Emathla (Jumper) King Payne Oscen Tustenuggee Cappachimico Thomas Perryman Kinache Peter McQueen | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Peak: 40,000 Expeditionary: 8,000[1] | 1,500[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Militia and civilian deaths unknown | Heavy | ||||||

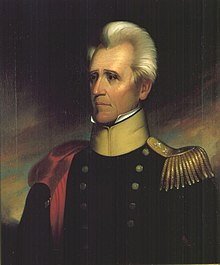

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were a series of three military conflicts between the United States and the Seminoles that took place in Florida between about 1816 and 1858. The Seminoles are a Native American nation which coalesced in northern Florida during the early 1700s, when the territory was still a Spanish colonial possession. Tensions grew between the Seminoles and settlers in the newly independent United States in the early 1800s, mainly because enslaved people regularly fled from Georgia into Spanish Florida, prompting slaveowners to conduct slave raids across the border. A series of cross-border skirmishes escalated into the First Seminole War, when American General Andrew Jackson led an incursion into the territory over Spanish objections. Jackson's forces destroyed several Seminole, Mikasuki and Black Seminole towns, as well as captured Fort San Marcos and briefly occupied Pensacola before withdrawing in 1818. The U.S. and Spain soon negotiated the transfer of the territory with the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819.

The United States gained possession of Florida in 1821 and coerced the Seminoles into leaving their lands in the Florida panhandle for a large Indian reservation in the center of the peninsula per the Treaty of Moultrie Creek. In 1832 by the Treaty of Payne's Landing, however, the federal government under United States President Andrew Jackson demanded that they leave Florida altogether and relocate to Indian Territory (modern day Oklahoma) as per the Indian Removal Act of 1830. A few bands reluctantly complied but most resisted violently, leading to the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), which was by far the longest and most wide-ranging of the three conflicts. Initially, less than 2000 Seminole warriors employed hit-and-run guerilla warfare tactics and knowledge of the land to evade and frustrate a combined U.S. Army and Marine force that grew to over 30,000. Instead of continuing to pursue these small bands, American commanders eventually changed their strategy and focused on seeking out and destroying hidden Seminole villages and crops, putting increasing pressure on resisters to surrender or starve with their families.

Most of the Seminole population had been relocated to Indian Territory or killed by the mid-1840s, though several hundred settled in central and southern Florida, where they were allowed to remain in an uneasy truce. Tensions over new settlement in the state under the Armed Occupation Act of 1842 south of Tampa led to renewed hostilities, and the Third Seminole War broke out in 1855. By the cessation of active fighting in 1858, the few remaining bands of Seminoles in Florida had fled deep into the Everglades to land unwanted by American settlers.

Taken together, the Seminole Wars were the longest, most expensive, and most deadly of all American Indian Wars.

Overview

Background

Spanish Florida was established in the 1500s, when Spain laid claim to land explored by several expeditions across the future southeastern United States. The introduction of diseases to the indigenous peoples of Florida caused a steep decline in the original native population over the following century, and most of the remaining Apalachee and Tequesta peoples settled in a series of missions spread out across north Florida. Spain never established real control over its vast claim outside of the immediate vicinity of its scattered missions and the towns of St. Augustine and Pensacola, however, and British settlers established several colonies along the Atlantic coast during the 1600s. After the establishment of the Province of Carolina in the late 17th century, a series of raids by British settlers from the Carolinas and their Indian allies into Spanish Florida devastated both the mission system and the remaining native population.

British settlers repeatedly came into conflict with Native Americans as the colonies expanded further westward, resulting in a stream of refugees relocating to depopulated areas of Florida. A majority of these refugees were Muscogee (Creek) Indians from Georgia and Alabama, and during the 1700s, they came together with other native peoples to establish independent chiefdoms and villages across the Florida panhandle as they coalesced into a new culture which became known as the Seminoles.[5]

Beginning in the 1730s, Spain established a policy of providing refuge to runaway slaves in an attempt to weaken the British Southern Colonies. Hundreds of Black people escaped slavery to Florida over the ensuing decades, with most settling near St. Augustine at Fort Mose and a few living amongst the Seminole, who treated them with varying levels of equality.[6] Their numbers increased during and after the American War of Independence, and it became common to find settlements of Black Seminoles either near Seminole towns or living independently, such as at Negro Fort on the Apalachicola River.[7] The presence of a nearby refuge for free Africans was considered a threat to the institution of chattel slavery in the southern United States, and settlers in the border states of Mississippi and Georgia in particular accused the Seminoles of inciting slaves to escape and then stealing their human property.[8] In retaliation, plantation owners organized repeated raids into Spanish Florida in which they captured Africans they accused of being escaped slaves and harassed the Seminole villages near the border, resulting in bands of Seminoles crossing into U.S. territory to stage reprisal attacks.[9]

First Seminole War

The increasing border tensions came to a head on December 26, 1817, as the U.S. War Department wrote an order directing General Andrew Jackson to take command in person and bring the Seminoles under control, precipitating the First Seminole War.[10] The war preceded with the destruction of the Negro Fort in July 1816, and subsequently Jackson's forces destroyed several Seminole/Creek and Miccosukee settlements including Fowltown pursuing them and Black Seminoles and allied Maroons across northern Florida in 1818. Jackson's expedition culminated in April 1818 with the Arbuthnot and Ambrister incident. The Spanish government expressed outrage over Jackson's "punitive expeditions"[11] into their territory and his brief occupation of Pensacola the capital of their colony of West Florida. But as was made clear by several local uprisings and other forms of "border anarchy",[11] Spain was no longer able to defend nor control Florida and eventually agreed to cede it to the United States per the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, with the transfer taking place in 1821.[12] According to the terms of the Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823) between the United States and Seminole Nation, the Seminoles were removed from Northern Florida to a reservation in the center of the Florida peninsula, and the United States constructed a series of forts and trading posts along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts to enforce the treaty.[2]

Second Seminole War

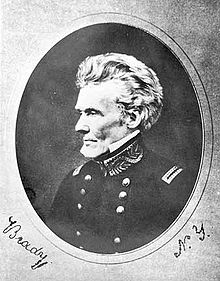

The Second Seminole War (1835–1842) began as a result of the United States unilaterally voiding the Treaty of Moultrie Creek and demanding that all Seminoles relocate to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma under the Indian Removal Act (1830). After several ultimatums and the departure of a few Seminole clans per the Treaty of Payne's Landing (1832), hostilities commenced in December 1835 with the Dade battle and continued for the next several years with a series of engagements throughout the peninsula and extending to the Florida Keys. Though the Seminole fighters were at a tactical and numerical disadvantage, Seminole military leaders effectively used guerrilla warfare to frustrate United States military forces, which eventually numbered over 30,000 regulars, militiamen and volunteers.[13] General Thomas Sidney Jesup was sent to Florida to take command of the campaign in 1836. Instead of futilely pursuing parties of Seminole fighters through the territory as previous commanders had done, Jesup changed tactics and engaged in finding, capturing or destroying Seminole homes, livestock, farms, and related supplies, thus starving them out; a strategy which would be duplicated by General W. T. Sherman in his march to the sea during the American Civil War. Jesup also authorized the controversial abduction of Seminole leaders Osceola and Micanopy by luring them under a false flag of truce.[14] General Jesup clearly violated the rules of war, and spent 21 years defending himself over it, "Viewed from the distance of more than a century, it hardly seems worthwhile to try to grace the capture with any other label than treachery."[15] By the early 1840s, many Seminoles had been killed, and many more were forced by impending starvation to surrender and be removed to Indian Territory. Though there was no official peace treaty, several hundred Seminoles remained in central and southern Florida after active conflict wound down.[2]

Third Seminole War

The Third Seminole War (1855–1858) was precipitated as an increasing number of settlers in central and southern Florida led to increasing tension with Seminoles and Miccosukees living in the area. In December 1855, U.S. Army personnel located and destroyed a large Seminole plantation west of the Everglades, perhaps to deliberately provoke a violent response that would result in the removal of the remaining Seminole citizens from the region. Holata Micco, a Seminole leader known as Billy Bowlegs by whites, responded with a raid near Fort Myers, leading to a series of retaliatory raids and small skirmishes with no large battles fought. Once again, the United States military strategy was to target Seminole civilians by destroying their food supply. By 1858, most of the remaining Seminoles, war weary and facing starvation, acquiesced to being removed to the Indian Territory in exchange for promises of safe passage and cash payments. An estimated 200 to 500 Seminoles in small family bands still refused to leave and retreated deep into the Everglades and the Big Cypress Swamp to live on land considered unsuitable by American settlers.[2]

Background

Colonial Florida

Decline of indigenous cultures

The original indigenous peoples of Florida declined significantly in number after the arrival of European explorers in the early 1500s, mainly because the Native Americans had little resistance to diseases newly introduced from Europe. Spanish suppression of native revolts further reduced the population in northern Florida until the early 1600s, at which time the establishment of a series of Spanish missions improved relations and stabilized the population.[16][17]

Beginning in the late-17th century, raids by British settlers from the colony of Carolina and their Indian allies began another steep decline in the indigenous population. By 1707, settlers based in Carolina and their Yamasee Indian allies had killed, carried off, or driven away most of the remaining native inhabitants during a series of raids across the Florida panhandle and down the full length of the peninsula. In the first decade of the 18th century. 10,000–12,000 Indians were taken as slaves according to the governor of La Florida and by 1710, observers noted that north Florida was virtually depopulated. The Spanish missions all closed, as without natives, there was nothing for them to do. The few remaining natives fled west to Pensacola and beyond or east to the vicinity of St. Augustine. When Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the majority of Florida's Indians travelled with the Spanish to Cuba or New Spain.[16][18][19]

Origin of the Seminoles

During the mid-1700s, small bands from various Native American tribes from the southeastern United States began moving into the unoccupied lands of Florida. In 1715, the Yamasee moved into Florida as allies of the Spanish, after conflicts with colonists from the Province of Carolina. Creek people, at first primarily the Lower Creek but later including Upper Creek, also started moving into Florida from the area of Georgia. The Mikasuki, Hitchiti-speakers, settled around what is now Lake Miccosukee near Tallahassee. (Descendants of this group have maintained a separate tribal identity as today's Miccosukee.)

Another group of Hitchiti speakers, led by Cowkeeper, settled in what is now Alachua County, an area where the Spanish had maintained cattle ranches in the 17th century. Because one of the best-known ranches was called la Chua, the region became known as the "Alachua Prairie". The Spanish in Saint Augustine began calling the Alachua Creek Cimarrones, which roughly meant "wild ones" or "runaways". This was the probable origin of the term "Seminole".[20][21] This name was eventually applied to the other groups in Florida, although the Indians still regarded themselves as members of different tribes. Other Native American groups in Florida during the Seminole Wars included the Choctaw, Yuchi, Spanish Indians (so called because it was believed that they were descended from Calusas), and "rancho Indians", who lived at Spanish/Cuban fishing camps (ranchos) on the Florida coast.[22]

In 1738, the Spanish governor of Florida, Manuel de Montiano, had Fort Mose built and established as a free Black settlement. Fugitive African and African American slaves who could reach the fort were essentially free. Many were from Pensacola; some were free citizens, though others had escaped from United States territory. The Spanish offered the slaves freedom and land in Florida. They recruited former slaves as militia to help defend Pensacola and Fort Mose. Other fugitive slaves joined Seminole bands as free members of the tribe.

Most of the former slaves at Fort Mose went to Cuba with the Spanish when they left Florida in 1763, while others lived with or near various bands of Indians. Fugitive slaves from the Carolinas and Georgia continued to make their way to Florida, as the Underground Railroad ran south. The Blacks who stayed with or later joined the Seminoles became integrated into the tribes, learning the languages, adopting the dress, and inter-marrying. The blacks knew how to farm and served as interpreters between the Seminole and the whites. Some of the Black Seminoles, as they were called, became important tribal leaders.[23]

Early conflict

During the American Revolutionary War, the British, who controlled Florida, recruited Seminoles to raid Patriot-aligned settlements on the Georgia frontier. The confusion of war allowed American slaves to escape to Florida, where local British authorities promised them their freedom for in exchange for military service. These events made the new United States enemies of the Seminoles. In 1783, as part of the treaty ending the Revolutionary War, Florida, was returned to Spain. Spain's grip on Florida was light, as it maintained only small garrisons at St. Augustine, St. Marks and Pensacola. They did not control the border between Florida and the United States and were unable to act against the State of Muskogee established in 1799, envisioned as a single nation of American Indians independent of both Spain and the United States, until 1803 when both nations conspired to entrap its founder. Mikasukis and other Seminole groups still occupied towns on the United States side of the border, while American squatters moved into Spanish Florida.[24]

The British had divided Florida into East Florida and West Florida in 1763, a division retained by the Spanish when they regained Florida in 1783. West Florida extended from the Apalachicola River to the Mississippi River. Together with their possession of Louisiana, the Spanish controlled the lower reaches of all of the rivers draining the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains. It prohibited the US from transport and trade on the lower Mississippi. In addition to its desire to expand west of the mountains, the United States wanted to acquire Florida. It wanted to gain free commerce on western rivers, and to prevent Florida from being used a base for possible invasion of the U.S. by a European country.[25]

The Louisiana Purchase

In order to obtain a port on the Gulf of Mexico with secure access for Americans, United States diplomats in Europe were instructed to try to purchase the Isle of Orleans and West Florida from whichever country owned them. When Robert Livingston approached France in 1803 about buying the Isle of Orleans, the French government offered to sell it and all of Louisiana as well. While the purchase of Louisiana exceeded their authorization, Livingston and James Monroe (who had been sent to help him negotiate the sale) in the deliberations with France pursued a claim that the area east of the Mississippi to the Perdido River was part of Louisiana. As part of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase treaty, France repeated verbatim Article 3 of its 1800 treaty with Spain, thus expressly subrogating the United States to the rights of France and Spain.[26]p. 288–291

The ambiguity in this third article lent itself to the purpose of U.S. envoy James Monroe, although he had to adopt an interpretation that France had not asserted, nor Spain allowed.[27]p 83 Monroe examined each clause of the third article and interpreted the first clause as if Spain since 1783 had considered West Florida as part of Louisiana. The second clause only served to render the first clause clearer. The third clause referred to the treaties of 1783 and 1795 and was designed to safeguard the rights of the United States. This clause then simply gave effect to the others.[27]p 84–85 According to Monroe, France never dismembered Louisiana while it was in her possession. (He regarded November 3, 1762, as the termination date of French possession, rather than 1769, when France formally delivered Louisiana to Spain).

President Thomas Jefferson had initially believed that the Louisiana Purchase included West Florida and gave the United States a strong claim to Texas.[28] President Jefferson asked U.S. officials in the border area for advice on the limits of Louisiana, the best informed of whom did not believe it included West Florida.[27]p 87-88 Later, in an 1809 letter, Jefferson virtually admitted that West Florida was not a possession of the United States.[29]p 46–47

During his negotiations with France, U.S. envoy Robert Livingston wrote nine reports to Madison in which he stated that West Florida was not in the possession of France.[29]p 43–44 In November 1804, in response to Livingston, France declared the American claim to West Florida absolutely unfounded.[27]p 113–116 Upon the failure of Monroe's later 1804–1805 mission, Madison was ready to abandon the American claim to West Florida altogether.[27]p 118 In 1805, Monroe's last proposition to Spain to obtain West Florida was absolutely rejected, and American plans to establish a customs house at Mobile Bay in 1804 were dropped in the face of Spanish protests.[26]p 293

The United States also hoped to acquire all of the Gulf coast east of Louisiana, and plans were made to offer to buy the remainder of West Florida (between the Perdido and Apalachicola rivers) and all of East Florida. It was soon decided, however, that rather than paying for the colonies, the United States would offer to assume Spanish debts to American citizens[Note 1] in return for Spain ceding the Floridas. The American position was that it was placing a lien on East Florida in lieu of seizing the colony to settle the debts.[31]

In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain, forced Ferdinand VII, King of Spain, to abdicate, and installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte as King. Resistance to the French invasion coalesced in a national government, the Cortes of Cádiz. This government then entered into an alliance with Britain against France. This alliance raised fears in the United States that the British would establish military bases in Spanish colonies, including the Floridas, and as such potentially compromise the security of the southern frontiers of the U.S.[32]

West Florida

By 1810, during the Peninsular War, Spain was largely overrun by the French army. Rebellions against the Spanish authorities broke out in many of its American colonies. Settlers in West Florida and in the adjacent Mississippi Territory started organizing in the summer of 1810 to seize Mobile and Pensacola, the last of which was outside the part of West Florida claimed by the United States.

Residents of westernmost West Florida (between the Mississippi and Pearl rivers) organized a convention at Baton Rouge in the summer of 1810. The convention was concerned about maintaining public order and preventing control of the district from falling into French hands; at first it tried to establish a government under local control that was nominally loyal to Ferdinand VII. After discovering that the Spanish governor of the district had appealed for military aid to put down an "insurrection", residents of the Baton Rouge District overthrew the local Spanish authorities on September 23 by seizing the Spanish fort in Baton Rouge. On September 26, the convention declared West Florida to be independent.[33]

Pro-Spanish, pro-American, and pro-independence factions quickly formed in the newly proclaimed republic. The pro-American faction appealed to the United States to annex the area and to provide financial aid. On October 27, 1810, U.S. President James Madison proclaimed that the United States should take possession of West Florida between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers, based on the tenuous claim that it was part of the Louisiana Purchase.[34]

Madison authorized William C. C. Claiborne, governor of the Territory of Orleans, to take possession of the territory. He entered the capital of St. Francisville with his forces on December 6, 1810, and Baton Rouge on December 10, 1810. The West Florida government opposed annexation, preferring to negotiate terms to join the Union. Governor Fulwar Skipwith proclaimed that he and his men would "surround the Flag-Staff and die in its defense".[35]: 308 Claiborne refused to recognize the legitimacy of the West Florida government, however, and Skipwith and the legislature eventually agreed to accept Madison's proclamation. Claiborne only occupied the area west of the Pearl River (the current eastern boundary of Louisiana).[36][37][Note 2]

Juan Vicente Folch y Juan, governor of West Florida, hoping to avoid fighting, abolished customs duties on American goods at Mobile, and offered to surrender all of West Florida to the United States if he had not received help or instructions from Havana or Veracruz by the end of the year.[38]

Fearing that France would overrun all of Spain, with the presumed result being that Spanish colonies would either fall under French control or be seized by the British, in January 1811, Madison requested the U.S. Congress pass legislation authorizing the United States to take "temporary possession" of any territory adjacent to the United States east of the Perdido River, i.e., the balance of West Florida and all of East Florida. The United States would be authorized to either accept transfer of territory from "local authorities" or occupy territory to prevent it falling into the hands of a foreign power other than Spain. Congress debated and passed, on January 15, 1811, the requested resolution in closed session, and provided that the resolution could be kept secret until as late as March 1812.[39]

American forces occupied most of the Spanish territory between the Pearl and Perdido rivers (today's coastal Mississippi and Alabama), with the exception of the area around Mobile, in 1811.[40] Mobile was occupied by United States forces in 1813.[41]

Madison sent George Mathews to deal with the disputes over West Florida. When Vicente Folch rescinded his offer to turn the remainder of West Florida over to the U.S., Mathews traveled to East Florida to engage the Spanish authorities there. When that effort failed, Mathews, in an extreme interpretation of his orders, schemed to incite a rebellion similar to that in the Baton Rouge District.[42]

Patriot War of East Florida (1812)

In 1812, General George Mathews was commissioned by President James Madison to approach the Spanish governor of East Florida in an attempt to acquire the territory. His instructions were to take possession of any part of the territory of the Floridas upon making "arrangement" with the "local authority" to deliver possession to the U.S. Barring that or invasion by another foreign power, they were not to take possession of any part of Florida.[43][44][45] Most of the residents of East Florida were happy with the status quo, so Mathews raised a force of volunteers in Georgia with a promise of arms and continued defense. On 16 March 1812, this force of "Patriots", with the aid of nine U.S. Navy gunboats, seized the town of Fernandina on Amelia Island, just south of the border with Georgia, approximately 50 miles north of St. Augustine.[46]

On March 17, the Patriots and the town's Spanish authorities signed articles of capitulation.[43] The next day, a detachment of 250 regular United States troops were brought over from Point Peter, Georgia, and the Patriots surrendered the town to Gen. George Mathews, who had the U.S. flag raised immediately.[44] As agreed, the Patriots held Fernandina for only one day before turning authority over to the U.S. military, an event that soon gave the U.S. control of the coast to St. Augustine. Within several days the Patriots, along with a regiment of regular Army troops and Georgian volunteers, moved toward St. Augustine. On this march the Patriots were slightly in advance of the American troops. The Patriots would proclaim possession of some ground, raise the Patriot flag, and as the "local authority" surrender the territory to the United States troops, who would then substitute the American flag for the Patriot flag. The Patriots faced no opposition as they marched, usually with Gen. Mathews.[44] Accounts of witnesses state that the Patriots could have made no progress but for the protection of the U.S. forces and could not have maintained their position in the country without the aid of the U.S. troops. The American troops and Patriots acted in close concert, marching, camping, foraging and fighting together. In this way, the American troops sustained the Patriots,[44] who, however, were unable to take the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine.

As soon as the U.S. government was notified of these events, Congress became alarmed at the possibility of being drawn into war with Spain, and the effort fell apart. Secretary of State James Monroe promptly disavowed the actions and relieved Gen. Mathews of his commission on May 9, on the grounds that neither of the instructed contingencies had occurred.[43] However, peace negotiations with the Spanish authorities were protracted and slow. Through the summer and autumn, the U.S. and Patriot troops foraged and plundered almost every plantation and farm, most of them having been abandoned by their owners. The troops helped themselves to everything they could find. Stored food was used up, growing crops destroyed or fed to horses, all types of movable property plundered or destroyed, buildings and fences burned, cattle and hogs killed or stolen for butchering, and slaves often dispersed or abducted. This continued until May 1813 and left the formerly inhabited parts in a state of desolation.[44]

In June 1812, George Mathews met with King Payne and other Seminole leaders. After the meeting, Mathews believed that the Seminoles would remain neutral in the conflict. Sebastián Kindelán y O'Regan, the governor of East Florida, tried to induce the Seminoles to fight on the Spanish side. Some of the Seminoles wanted to fight the Georgians in the Patriot Army, but King Payne and others held out for peace. The Seminoles were not happy with Spanish rule, comparing their treatment under the Spanish unfavorably with that received from the British when they held Florida. Ahaya, or Cowkeeper, King Payne's predecessor, had sworn to kill 100 Spaniards, and on his deathbed lamented having killed only 84. At a second conference with the Patriot Army leaders, the Seminoles again promised to remain neutral.[47]

The blacks living in Florida outside of St. Augustine, many of whom were former slaves from Georgia and South Carolina, were not disposed to be neutral. Often slaves in name only to Seminoles, they lived in freedom and feared loss of that freedom if the United States took Florida away from Spain. Many blacks enlisted in the defense of St. Augustine, while others urged the Seminoles to fight the Patriot Army. In a third meeting with Seminole leaders, the Patriot Army leaders threatened the Seminoles with destruction if they fought on the side of the Spanish. This threat gave the Seminoles favoring war, led by King Payne's brother Bolek (also known as Bowlegs) the upper hand. Joined by warriors from Alligator (near present-day Lake City) and other towns, the Seminoles sent 200 Indians and 40 blacks to attack the Patriots.[48]

In retaliation for Seminole raids, in September 1812, Colonel Daniel Newnan led 117 Georgia militiamen in an attempt to seize the Alachua Seminole lands around Payne's Prairie. Newnan's force never reached the Seminole towns, losing eight men dead, eight missing, and nine wounded after battling Seminoles for more than a week. Four months later Lt. Colonel Thomas Adams Smith led 220 U.S. Army regulars and Tennessee volunteers in a raid on Payne's Town, the chief town of the Alachua Seminoles. Smith's force found a few Indians, but the Alachua Seminoles had abandoned Payne's Town and moved southward. After burning Payne's Town, Smith's force returned to American held territory.[49]

Negotiations concluded for the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 1813. On May 6, 1813, the army lowered the flag at Fernandina and crossed the St. Marys River to Georgia with the remaining troops.[50][51]

District of Elotchaway

After the United States government disavowed support of the Territory of East Florida and withdrew American troops and ships from Spanish territory, most of the Patriots in East Florida either withdrew to Georgia or accepted the offer of amnesty from the Spanish government.[52] Some of the Patriots still dreamed of claiming land in Florida. One of them, Buckner Harris, had been involved in recruiting men for the Patriot Army[53] and was the President of the Legislative Council of the Territory of East Florida.[54] Harris became the leader of a small band of Patriots who roamed the countryside threatening residents who had accepted pardons from the Spanish government.[55]

Buckner Harris developed a plan to establish a settlement in the Alachua Country[Note 3] with financial support from the State of Georgia, the cession of land by treaty from the Seminoles, and a land grant from Spain. Harris petitioned the governor of Georgia for money, stating that a settlement of Americans in the Alachua Country would help keep the Seminoles away from the Georgia border, and would be able to intercept runaway slaves from Georgia before they could reach the Seminoles. Unfortunately for Harris, Georgia did not have funds available. Harris also hoped to acquire the land around the Alachua Prairie (Paynes Prairie) by treaty from the Seminoles but could not persuade the Seminoles to meet with him. The Spanish were also not interested in dealing with Harris.[57]

In January 1814, 70 men led by Buckner Harris crossed from Georgia into East Florida, headed for the Alachua Country. More men joined them as they traveled through East Florida, with more than 90 in the group when they reached the site of Payne's Town, which had been burned in 1812. The men built a 25-foot square, two-story blockhouse, which they named Fort Mitchell, after David Mitchell, former governor of Georgia and a supporter of the Patriot invasion of East Florida.[Note 4] By the time the blockhouse was completed, there were reported to be more than 160 men present in Elotchaway. On January 25, 1814, the settlers established a government, titled "The District of Elotchaway of the Republic of East Florida", with Buckner Harris as Director. The Legislative Council then petitioned the United States Congress to accept the District of Elotchaway as a territory of the United States.[60][61] The petition was signed by 106 "citizens of Elotchaway." The Elotchaway settlers laid out farm plots and started planting crops.[62][63] Some of the men apparently had brought families with them, as a child was born in Elotchaway on March 15, 1814.[64]

Buckner Harris hoped to expand American settlement in the Alachua Country and rode out alone to explore the area. On May 5, 1814, he was ambushed and killed by Seminoles. Without Harris, the District of Elotchaway collapsed. Fort Mitchell was abandoned, with all the settlers gone within two weeks.[65] Some of the men at Fort Mitchell who signed the petition to Congress settled again in the Alachua Country after Florida was transferred to the United States in 1821.[66]

The Creek War, the War of 1812 and the Negro Fort

During the Creek War (1813–1814), Colonel Andrew Jackson became a national hero with his victory over the Creek Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. After this victory, Jackson forced the Treaty of Fort Jackson on the Creek, resulting in the loss of much Creek territory in what is today southern Georgia and central and southern Alabama. As a result, many Creek left Alabama and Georgia, and moved to Spanish West Florida. The Creek refugees joined the Seminole of Florida.[67]

In 1814, Britain was still at war with the United States, and in May, a British force entered the mouth of the Apalachicola River, and moved upriver to begin building a fort at Prospect Bluff.[68] This British Post at Prospect Bluff harbored Native American refugees from the Creek War following their demise at the Battle of Horsehoe Bend. A company of Royal Marines, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Nicolls, was to subsequently arrive, but was invited to relocate to Pensacola in late August 1814.[69] It was estimated, by Captain Nicholas Lockyer of HMS Sophie, that in August 1814 there were 1,000 Indians at Pensacola, of whom 700 were warriors.[70] Two months after the British and their Indian allies were beaten back from an attack on Fort Bowyer near Mobile, a U.S. force led by General Jackson drove the British and Spanish out of Pensacola, and back to the Apalachicola River. They managed to continue work on the fort at Prospect Bluff.

When the War of 1812 ended, all British forces left the Gulf of Mexico except for Nicolls and his forces in Spanish West Florida. He directed the provisioning of the fort at Prospect Bluff with cannon, muskets, and ammunition. He told his Native American allies that the Treaty of Ghent guaranteed the return of all Indian lands lost to the United States during the War of 1812, including the Creek lands in Georgia and Alabama.[71] Before Nicolls left in the spring of 1815, he turned the fort over to the maroons and Native American allies whom he had originally recruited for possible incursions into U.S. territory during the war. (see Corps of Colonial Marines). As word spread in the American Southeast about the fort, white Americans called it the "Negro Fort." Americans worried that it would inspire their slaves to escape to Florida or revolt.[72]

Acknowledging that it was in Spanish territory, in April 1816, Jackson informed Governor José Masot of West Florida that if the Spanish did not eliminate the fort, he would. The governor replied that he did not have the forces to take the fort.[citation needed]

Jackson assigned Brigadier General Edmund Pendleton Gaines to take control of the fort. Gaines directed Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch to build Fort Scott on the Flint River just north of the Florida border. Gaines said he intended to supply Fort Scott from New Orleans via the Apalachicola River. As this would mean passing through Spanish territory and past the Negro Fort, it would allow the U.S. Army to keep an eye on the Seminole and the Negro Fort. If the fort fired on the supply boats, the Americans would have an excuse to destroy it.[73]

In July 1816, a supply fleet for Fort Scott reached the Apalachicola River. Clinch took a force of more than 100 American soldiers and about 150 Lower Creek warriors, including the chief Tustunnugee Hutkee (White Warrior), to protect their passage. The supply fleet met Clinch at the Negro Fort, and its two gunboats took positions across the river from the fort. The inhabitants of the fort fired their cannon at the invading U.S. soldiers and the Creek but had no training in aiming the weapon. The American military fired back, and the gunboats' ninth shot, a "hot shot" (a cannonball heated to a red glow), landed in the fort's powder magazine. The explosion leveled the fort and was heard more than 100 miles (160 km) away in Pensacola.[citation needed] It has been called "the single deadliest cannon shot in American history."[74] Of the 320 people known to be in the fort, including women and children, more than 250 died instantly, and many more died from their injuries soon after. Once the US Army destroyed the fort, it withdrew from Spanish Florida.

American squatters and outlaws raided the Seminole, killing villagers and stealing their cattle. Seminole resentment grew and they retaliated by stealing back the cattle.[citation needed] On February 24, 1817, a raiding party killed Mrs. Garrett, a woman living in Camden County, Georgia, and her two young children.[75][76]

Fowltown and the Scott Massacre

Fowltown was a Mikasuki (Creek) village in southwestern Georgia, about 15 miles (24 km) east of Fort Scott. Chief Neamathla of Fowltown got into a dispute with the commander of Fort Scott over the use of land on the eastern side of the Flint River, essentially claiming Mikasuki sovereignty over the area. The land in southern Georgia had been ceded by the Creeks in the Treaty of Fort Jackson, but the Mikasukis did not consider themselves Creek, did not feel bound by the treaty which they had not signed, and did not accept that the Creeks had any right to cede Mikasuki land. On November 21, 1817, General Gaines sent a force of 250 men to seize Fowltown. The first attempt was beaten off by the Mikasukis. The next day, November 22, 1817, the Mikasukis were driven from their village. Some historians date the start of the war to this attack on Fowltown. David Brydie Mitchell, former governor of Georgia and Creek Indian agent at the time, stated in a report to Congress that the attack on Fowltown was the start of the First Seminole War.[77]

A week later a boat carrying supplies for Fort Scott, under the command of Lieutenant Richard W. Scott, was attacked on the Apalachicola River. There were forty to fifty people on the boat, including twenty sick soldiers, seven wives of soldiers, and possibly some children. (While there are reports of four children being killed by the Seminoles, they were not mentioned in early reports of the massacre, and their presence has not been confirmed.) Most of the boat's passengers were killed by the Indians. One woman was taken prisoner, and six survivors made it to the fort.[78]

While General Gaines had been under orders not to invade Florida, he later decided to allow short intrusions into Florida. When news of the Scott Massacre on the Apalachicola reached Washington, Gaines was ordered to invade Florida and pursue the Indians but not to attack any Spanish installations. However, Gaines had left for East Florida to deal with pirates who had occupied Fernandina. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun then ordered Andrew Jackson to lead the invasion of Florida.[79]

First Seminole War

There is no consensus about the beginning and ending dates for the First Seminole War. The U.S. Army Infantry indicates that it lasted from 1814 until 1819.[80] The U.S. Navy Naval Historical Center gives dates of 1816–1818.[36] Another Army site dates the war as 1817–1818.[81] Finally, the unit history of the 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery describes the war as occurring solely in 1818.[82]

East Florida (east side of Apalachicola River)

Jackson gathered his forces at Fort Scott in March 1818, including 800 U.S. Army regulars, 1,000 Tennessee volunteers, 1,000 Georgia militia,[83] and about 1,400 friendly Lower Creek warriors (under command of Brigadier General William McIntosh, a Creek chief). On March 15, Jackson's army entered Florida, marching down the banks of the Apalachicola River. When they reached the site of the Negro Fort, Jackson had his men construct a new fort, Fort Gadsden. The army then set out for the Mikasuki villages around Lake Miccosukee. The Indian town of Anhaica (today's Tallahassee) was burned on March 31, and the town of Miccosukee was taken the next day. More than 300 Indian homes were destroyed. Jackson then turned south, reaching Fort St. Marks (San Marcos) on April 6.[84]

Upon reaching St. Marks, Jackson wrote to the commandant of the fort, Don Francisco Caso y Luengo, to tell him that he had invaded Florida at the President's instruction.[85] He wrote that after capturing the wife of Chief Chennabee, she had testified to the Seminoles retrieving ammunition from the fort.[85] He explained that, because of this, the fort had already been taken over by the people living in the Mekasukian towns he had just destroyed and to prevent that from happening again, the fort would have to be guarded by American troops.[85] He justified this on the "principal of self defense."[85] By claiming that through this action he was a "Friend of Spain", Jackson was attempting to take possession of St. Marks by convincing the Spanish that they were allies with the American army against the Seminoles.[85] Luengo responded, agreeing that he and Jackson were allies but denying the story that Chief Chennabee's wife had told, claiming that the Seminoles had not taken ammunition from or possession of the fort.[85] He expressed to Jackson that he was worried about the challenges he would face if he allowed American troops to occupy the fort without first getting authorization from Spain.[85] Despite Leungo asking him not to occupy the fort, Jackson seized St. Marks on April 7.[85] There he found Alexander George Arbuthnot, a Scottish trader based out of the Bahamas. He traded with the Indians in Florida and had written letters to British and American officials on behalf of the Indians. He was rumored to be selling guns to the Indians and to be preparing them for war. He probably was selling guns, since the main trade item of the Indians was deer skins, and they needed guns to hunt the deer.[86] Two Indian leaders, Josiah Francis (Hillis Hadjo), a Red Stick Creek also known as the "Prophet" (not to be confused with Tenskwatawa), and Homathlemico, had been captured when they had gone out to an American ship flying the Union Flag that had anchored off of St. Marks. As soon as Jackson arrived at St. Marks, the two Indians were brought ashore and hanged without trial.[86]

Jackson left Fort St. Marks to attack the Native American Bolek's (aka "Bowlegs") old town and maroon villages (Nero's town) along the Suwannee River near the current Old Town, FL. On April 12, enroute to the Suwannee the U.S. army and allied Native Americans led by William McIntosh, found and attacked a Red Stick village led by Peter McQueen on the Econfina River. Close to 40 Red Sticks were killed, and about 100 women and children were captured.[citation needed] In the village, they found Elizabeth Stewart, the woman who had been captured in the attack (the Scott Massacre) on the supply boat on the Apalachicola River the previous November near modern Chattahochee, FL. Having destroyed the major Seminole and black villages, Jackson declared victory and sent the Georgia militiamen and the Lower Creeks home. The remaining army then returned to Fort St. Marks.[87]

About this time, Robert Ambrister, a former officer in the Corps of Colonial Marines, was captured by Jackson's troops. At St. Marks a military tribunal was convened, and Ambrister and Arbuthnot were charged with aiding the Seminoles and the Spanish, inciting them to war and leading them against the United States. Ambrister threw himself on the mercy of the court, while Arbuthnot maintained his innocence, saying that he had only been engaged in legal trade. The tribunal sentenced both men to death but then relented and changed Ambrister's sentence to fifty lashes and a year at hard labor. Jackson, however, reinstated Ambrister's death penalty. Ambrister was executed by a firing squad of American troops on April 29, 1818. Arbuthnot was hanged from the yardarm of his own ship.[88]

Jackson left a garrison at Fort St. Marks and returned to Fort Gadsden. Jackson had first reported that all was peaceful and that he would be returning to Nashville, Tennessee.

West Florida (west of the Apalachicola River)

General Jackson later reported that Indians were gathering and being supplied by the Spanish, and he left Fort Gadsden with 1,000 men on May 7, headed for Pensacola. The governor of West Florida protested that most of the Indians at Pensacola were women and children and that the men were unarmed, but Jackson did not stop. Jackson also stated (in a letter to George W. Campbell) that the seizure of supplies meant for Fort Crawford gave additional reason for his march on Pensacola.[89] When he reached Pensacola on May 23, the governor and the 175-man Spanish garrison retreated to Fort Barrancas, leaving the city of Pensacola to Jackson. The two sides exchanged cannon fire for a couple of days, and then the Spanish surrendered Fort Barrancas on May 28. Jackson left Colonel William King as military governor of West Florida and went home.[90]

Consequences

There were international repercussions to Jackson's actions. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had just started negotiations with Spain for the purchase of Florida. Spain protested the invasion and seizure of West Florida and suspended the negotiations. Spain did not have the means to retaliate against the United States or regain West Florida by force, so Adams let the Spanish officials protest, then issued a letter (with 72 supporting documents) claiming that the United States was defending her national interests against the British, Spanish and Native Americans. In the letter he also apologized for the seizure of West Florida, said that it had not been American policy to seize Spanish territory, and offered to give St. Marks and Pensacola back to Spain. This notably did not include the return of Fort Gadsden.[91]

The British government protested the execution of two of its subjects who had never entered United States territory. A number of British commentators discussed the possibility of demanding reparations and taking reprisals. At the end, Britain refused to risk another war with the United States due to a variety of factors, including the increasing importance of British trade with the United States, particularly in grain and cotton.[92] British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh chose not to let the incident interfere with the warming relations between the two countries, and continued on with plans for the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.[91]

Spain, seeing that the British would not join them in making a strong denouncement of the Florida invasion, accepted and eventually resumed negotiations for the sale of Florida.[93] Defending Jackson's actions as necessary, and sensing that they strengthened his diplomatic standing, Adams demanded Spain either control the inhabitants of East Florida or cede it to the United States. An agreement was then reached whereby Spain ceded East Florida to the United States and renounced all claim to West Florida.[94]

There were also repercussions in America. Congressional committees held hearings into the irregularities of the Ambrister and Arbuthnot trials. While most Americans supported Jackson, some worried that Jackson could become a "man on horseback", a second Napoleon, and transform the United States into a military dictatorship. When Congress reconvened in December 1818, resolutions were introduced condemning Jackson's actions. Jackson was too popular, and the resolutions failed, but the Ambrister and Arbuthnot executions left a stain on his reputation for the rest of his life, although it was not enough to keep him from becoming president.[95]

First Interbellum

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1819 with the Adams–Onís Treaty, and the United States took possession in 1821. Effective government was slow in coming to Florida. General Andrew Jackson was appointed military governor in March 1821, but he did not arrive in Pensacola until July. He resigned the post in September and returned home in October, having spent just three months in Florida. His successor, William P. Duval, was not appointed until April 1822, and he left for an extended visit to his home in Kentucky before the end of the year. Other official positions in the territory had similar turn-over and absences.[96]

The Seminoles were still a problem for the new government. In early 1822, Capt. John R. Bell, provisional secretary of the Florida territory and temporary agent to the Seminoles, prepared an estimate of the number of Indians in Florida. He reported about 22,000 Indians, and 5,000 slaves held by Indians. He estimated that two-thirds of them were refugees from the Creek War, with no valid claim (in the U.S. view) to Florida. Indian settlements were located in the areas around the Apalachicola River, along the Suwannee River, from there south-eastwards to the Alachua Prairie, and then south-westward to a little north of Tampa Bay.[97]

Officials in Florida were concerned from the beginning about the situation with the Seminoles. Until a treaty was signed establishing a reservation, the Indians were not sure of where they could plant crops and expect to be able to harvest them, and they had to contend with white squatters moving into land they occupied. There was no system for licensing traders, and unlicensed traders were supplying the Seminoles with liquor. However, because of the part-time presence and frequent turnover of territorial officials, meetings with the Seminoles were canceled, postponed, or sometimes held merely to set a time and place for a new meeting.[98]

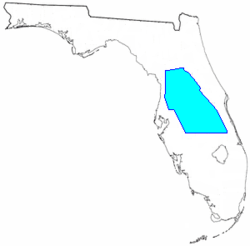

Treaty of Moultrie Creek

In 1823, the government decided to settle the Seminole on a reservation in the central part of the territory. A meeting to negotiate a treaty was scheduled for early September 1823 at Moultrie Creek, south of St. Augustine. About 425 Seminole attended the meeting, choosing Neamathla to be their chief representative or Speaker. Under the terms of the treaty negotiated there, the Seminole were forced to go under the protection of the United States and give up all claim to lands in Florida, in exchange for a reservation of about four million acres (16,000 km2). The reservation would run down the middle of the Florida peninsula from just north of present-day Ocala to a line even with the southern end of Tampa Bay. The boundaries were well inland from both coasts, to prevent contact with traders from Cuba and the Bahamas. Neamathla and five other chiefs were allowed to keep their villages along the Apalachicola River.[99]

Under the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the US was obligated to protect the Seminole as long as they remained law-abiding. The government was supposed to distribute farm implements, cattle and hogs to the Seminole, compensate them for travel and losses involved in relocating to the reservation, and provide rations for a year, until the Seminoles could plant and harvest new crops. The government was also supposed to pay the tribe US$5,000 per year for twenty years and provide an interpreter, a school and a blacksmith for twenty years. In turn, the Seminole had to allow roads to be built across the reservation and had to apprehend and return to US jurisdiction any runaway slaves or other fugitives.[100]

Implementation of the treaty stalled. Fort Brooke, with four companies of infantry, was established on the site of present-day Tampa in early 1824, to show the Seminole that the government was serious about moving them onto the reservation. However, by June James Gadsden, who was the principal author of the treaty and charged with implementing it, was reporting that the Seminole were unhappy with the treaty and were hoping to renegotiate it. Fear of a new war crept in. In July, Governor DuVal mobilized the militia and ordered the Tallahassee and Miccosukee chiefs to meet him in St. Marks. At that meeting, he ordered the Seminole to move to the reservation by October 1, 1824.[101]

The move had not begun, but DuVal began paying the Seminole compensation for the improvements they were having to leave as an incentive to move. He also had the promised rations sent to Fort Brooke on Tampa Bay for distribution. The Seminole finally began moving onto the reservation, but within a year some returned to their former homes between the Suwannee and Apalachicola rivers. By 1826, most of the Seminole had gone to the reservation, but were not thriving. They had to clear and plant new fields, and cultivated fields suffered in a long drought. Some of the tribe were reported to have starved to death. Both Col. George M. Brooke, commander of Fort Brooke, and Governor DuVal wrote to Washington seeking help for the starving Seminole, but the requests got caught up in a debate over whether the people should be moved to west of the Mississippi River. For five months, no additional relief reached the Seminole.[102]

The Seminoles slowly settled into the reservation, although they had isolated clashes with whites. Fort King was built near the reservation agency, at the site of present-day Ocala, and by early 1827 the Army could report that the Seminoles were on the reservation and Florida was peaceful. During the five-year peace, some settlers continued to call for removal. The Seminole were opposed to any such move, and especially to the suggestion that they join their Creek relations. Most whites regarded the Seminole as simply Creeks who had recently moved to Florida, while the Seminole claimed Florida as their home and denied that they had any connection with the Creeks.[103]

The Seminoles and slave catchers argued over the ownership of slaves. New plantations in Florida increased the pool of slaves who could escape to Seminole territory. Worried about the possibility of an Indian uprising and/or a slave rebellion, Governor DuVal requested additional Federal troops for Florida, but in 1828 the US closed Fort King. Short of food and finding the hunting declining on the reservation, the Seminole wandered off to get food. In 1828, Andrew Jackson, the old enemy of the Seminoles, was elected President of the United States. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act he promoted, which was to resolve the problems by moving the Seminole and other tribes west of the Mississippi.[104]

Treaty of Payne's Landing

In the spring of 1832, the Seminoles on the reservation were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Oklawaha River. The treaty negotiated there called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land were found to be suitable. They were to settle on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek tribe. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several months and conferring with the Creeks who had already been settled there, the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833, that the new land was acceptable. Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did not have the power to decide for all the tribes and bands that resided on the reservation.[105] The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834.[106]

The United States Senate finally ratified the Treaty of Payne's Landing in April 1834. The treaty had given the Seminoles three years to move west of the Mississippi. The government interpreted the three years as starting 1832 and expected the Seminoles to move in 1835. Fort King was reopened in 1834. A new Seminole agent, Wiley Thompson, had been appointed in 1834, and the task of persuading the Seminoles to move fell to him. He called the chiefs together at Fort King in October 1834 to talk to them about the removal to the west. The Seminoles informed Thompson that they had no intention of moving and that they did not feel bound by the Treaty of Payne's Landing. Thompson then requested reinforcements for Fort King and Fort Brooke, reporting that, "the Indians after they had received the Annuity, purchased an unusually large quantity of Powder & Lead." General Clinch also warned Washington that the Seminoles did not intend to move and that more troops would be needed to force them to move. In March 1835, Thompson called the chiefs together to read a letter from Andrew Jackson to them. In his letter, Jackson said, "Should you ... refuse to move, I have then directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force." The chiefs asked for thirty days to respond. A month later, the Seminole chiefs told Thompson that they would not move west. Thompson and the chiefs began arguing, and General Clinch had to intervene to prevent bloodshed. Eventually, eight of the chiefs agreed to move west but asked to delay the move until the end of the year, and Thompson and Clinch agreed.[107]

Five of the most important of the Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminoles, had not agreed to the move. In retaliation, Thompson declared that those chiefs were removed from their positions. As relations with the Seminoles deteriorated, Thompson forbade the sale of guns and ammunition to the Seminoles. Osceola, a young warrior beginning to be noticed particularly by the white settlers, was particularly upset by the ban, feeling that it equated Seminoles with slaves and said, "The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood; and then blacken him in the sun and rain ... and the buzzard live upon his flesh." In spite of this, Thompson considered Osceola to be a friend and gave him a rifle. Later, though, when Osceola was causing trouble, Thompson had him locked up at Fort King for a night. The next day, in order to secure his release, Osceola agreed to abide by the Treaty of Payne's Landing and to bring his followers in.[108]

The situation grew worse. On June 19, 1835, a group of whites searching for lost cattle found a group of Indians sitting around a campfire cooking the remains of what they claimed was one of their herd. The whites disarmed and proceeded to whip the Indians, when two more arrived and opened fire on the whites. Three whites were wounded, and one Indian was killed and one wounded, at what became known as the skirmish at Hickory Sink. After complaining to Indian Agent Thompson and not receiving a satisfactory response, the Seminoles became further convinced that they would not receive fair compensations for their complaints of hostile treatment by the settlers. Believed to be in response for the incident at Hickory Sink, in August 1835, Private Kinsley Dalton (for whom Dalton, Georgia, is named) was killed by Seminoles as he was carrying the mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King.[109]

Throughout the summer of 1835, the Seminole who had agreed to leave Florida were gathered at Fort King, as well as other military posts. From these gathering places, they would be sent to Tampa Bay where transports would then take them to New Orleans, destined eventually for reservations out west. However, the Seminole ran into issues getting fair prices for the property they needed to sell (chiefly livestock and slaves). Furthermore, there were issues with furnishing the Seminole with proper clothing. These issues led many Seminoles to think twice about leaving Florida.[110]

In November 1835 Chief Charley Emathla, wanting no part of a war, agreed to removal and sold his cattle at Fort King in preparation for moving his people to Fort Brooke to emigrate to the west. This act was considered a betrayal by other Seminoles who months earlier declared in council that any Seminole chief who sold his cattle would be sentenced to death. Osceola met Charley Emathla on the trail back to his village and killed him, scattering the money from the cattle purchase across his body.[111]

Second Seminole War

As Florida officials realized the Seminole would resist relocation, preparations for war began. Settlers fled to safety as Seminole attacked plantations and a militia wagon train. Two companies totaling 110 men under the command of Major Francis L. Dade were sent from Fort Brooke to reinforce Fort King in mid-December 1835. On the morning of December 28, the train of troops was ambushed by a group of Seminole warriors under the command of Alligator near modern-day Bushnell, Florida. The entire command and their small cannon were destroyed, with only two badly wounded soldiers surviving to return to Fort Brooke. Over the next few months Generals Clinch, Gaines and Winfield Scott, as well as territorial governor Richard Keith Call, led large numbers of troops in futile pursuits of the Seminoles. In the meantime, the Seminoles struck throughout the state, attacking isolated farms, settlements, plantations and Army forts, even burning the Cape Florida lighthouse. Supply problems and a high rate of illness during the summer caused the Army to abandon several forts.[112]

On Dec. 28, 1835, Major Benjamine A. Putnam with a force of soldiers occupied the Bulow Plantation and fortified it with cotton bales and a stockade. Local planters took refuge with their slaves. The Major abandoned the site on January 23, 1836, and the Bulow Plantation was later burned by the Seminoles. Now a State Park, the site remains a window into the destruction of the conflict; the massive stone ruins of the huge Bulow sugar mill stand little changed from the 1830s. By February 1836 the Seminole and black allies had attacked 21 plantations along the river.

Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock was among those who found the remains of the Dade party in February. In his journal he wrote of the discovery and expressed his discontent:

The government is in the wrong, and this is the chief cause of the persevering opposition of the Indians, who have nobly defended their country against our attempt to enforce a fraudulent treaty. The natives used every means to avoid a war, but were forced into it by the tyranny of our government.[113]

On November 21, 1836, at the Battle of Wahoo Swamp, the Seminole fought against American allied forces numbering 2500, successfully driving them back.; among the American dead was Major David Moniac, the first Native American graduate of West Point.[114] The skirmish restored Seminole confidence, showing their ability to hold their ground against their old enemies the Creek and white settlers.

Late in 1836, Major General Thomas Jesup, US Quartermaster, was placed in command of the war. Jesup brought a new approach to the war. He concentrated on wearing the Seminoles down rather than sending out large groups who were more easily ambushed. He needed a large military presence in the state to control it, and he eventually brought a force of more than 9,000 men into the state under his command. "Letters went off to the governors of the adjacent states calling for regiments of twelve-months volunteers. In stressing his great need, Jesup did not hesitate to mention a fact harrowing to his correspondents. "This is a negro not an Indian war."[115] Resulting in about half of the force volunteering as volunteers and militia. It also included a brigade of Marines, and Navy and Revenue-Marine personnel patrolling the coast and inland rivers and streams.[116]

In January 1837, the Army began to achieve more tangible successes, capturing or killing numerous Indians and blacks. At the end of January, some Seminole chiefs sent messengers to Jesup, and arranged a truce. In March a "Capitulation" was signed by several chiefs, including Micanopy, stipulating that the Seminole could be accompanied by their allies and "their negroes, their bona fide property", in their removal to the West. By the end of May, many chiefs, including Micanopy, had surrendered. Two important leaders, Osceola and Sam Jones (a.k.a. Abiaca, Ar-pi-uck-i, Opoica, Arpeika, Aripeka, Aripeika), had not surrendered, however, and were known to be vehemently opposed to relocation. On June 2 these two leaders with about 200 followers entered the poorly guarded holding camp at Fort Brooke and led away the 700 Seminoles who had surrendered. The war was on again, and Jesup decided against trusting the word of an Indian again. On Jesup's orders, Brigadier General Joseph Marion Hernández commanded an expedition that captured several Indian leaders, including Coacoochee (Wild Cat), John Horse, Osceola and Micanopy when they appeared for conferences under a white flag of truce. Coacoochee and other captives, including John Horse, escaped from their cell at Fort Marion in St. Augustine,[117] but Osceola did not go with them. He died in prison, probably of malaria.[118]

Jesup organized a sweep down the peninsula with multiple columns, pushing the Seminoles further south. On Christmas Day 1837, Colonel Zachary Taylor's column of 800 men encountered a body of about 400 warriors on the north shore of Lake Okeechobee. The Seminole were led by Sam Jones, Alligator and the recently escaped Coacoochee; they were well positioned in a hammock surrounded by sawgrass with half a mile of swamp in front of it. On the far side of the hammock was Lake Okeechobee. Here the saw grass stood five feet high. The mud and water were three feet deep. Horses would be of no use. The Seminole had chosen their battleground. They had sliced the grass to provide an open field of fire and had notched the trees to steady their rifles. Their scouts were perched in the treetops to follow every movement of the troops coming up. As Taylor's army came up to this position, he decided to attack.

At about half past noon, with the sun shining directly overhead and the air still and quiet, Taylor moved his troops squarely into the center of the swamp. His plan was to attack directly rather than try to encircle the Indians. All his men were on foot. In the first line were the Missouri volunteers. As soon as they came within range, the Seminoles opened fire. The volunteers broke, and their commander Colonel Gentry, fatally wounded, was unable to rally them. They fled back across the swamp. The fighting in the saw grass was deadliest for five companies of the Sixth Infantry; every officer but one, and most of their noncoms, were killed or wounded. When those units retired a short distance to re-form, they found only four men of these companies unharmed. The US eventually drove the Seminoles from the hammock, but they escaped across the lake. Taylor lost 26 killed and 112 wounded, while the Seminoles casualties were eleven dead and fourteen wounded. The US claimed the Battle of Lake Okeechobee as a great victory.[119][120]

At the end of January, Jesup's troops caught up with a large body of Seminoles to the east of Lake Okeechobee. Originally positioned in a hammock, the Seminoles were driven across a wide stream by cannon and rocket fire and made another stand. They faded away, having inflicted more casualties than they suffered, and the Battle of Loxahatchee was over. In February 1838, the Seminole chiefs Tuskegee and Halleck Hadjo approached Jesup with the proposal to stop fighting if they could stay in the area south of Lake Okeechobee, rather than relocating west. Jesup favored the idea but had to gain approval from officials in Washington for approval. The chiefs and their followers camped near the Army while awaiting the reply. When the secretary of war rejected the idea, Jesup seized the 500 Indians in the camp, and had them transported to the Indian Territory.[121]

In May, Jesup's request to be relieved of command was granted, and Zachary Taylor assumed command of the Army in Florida. With reduced forces, Taylor concentrated on keeping the Seminole out of northern Florida by building many small posts at twenty-mile (30 km) intervals across the peninsula, connected by a grid of roads. The winter season was fairly quiet, without major actions. In Washington and around the country, support for the war was eroding. Many people began to think the Seminoles had earned the right to stay in Florida. Far from being over, the war had become very costly. President Martin Van Buren sent the Commanding General of the Army, Alexander Macomb, to negotiate a new treaty with the Seminoles. On May 19, 1839, Macomb announced an agreement. In exchange for a reservation in southern Florida, the Seminoles would stop fighting.[122]

As the summer passed, the agreement seemed to be holding. However, on July 23, some 150 Indians attacked a trading post on the Caloosahatchee River; it was guarded by a detachment of 23 soldiers under the command of Colonel William S. Harney. He and some soldiers escaped by the river, but the Seminoles killed most of the garrison, as well as several civilians at the post. Many blamed the "Spanish" Indians, led by Chakaika, for the attack, but others suspected Sam Jones, whose band of Mikasuki had agreed to the treaty with Macomb. Jones, when questioned, promised to turn the men responsible for the attack over to Harney in 33 days. Before that time was up, two soldiers visiting Jones' camp were killed.[123]

The Army turned to bloodhounds to track the Indians, with poor results. Taylor's blockhouse and patrol system in northern Florida kept the Seminoles on the move but could not clear them out. In May 1839, Taylor, having served longer than any preceding commander in the Florida war, was granted his request for a transfer and replaced by Brig. Gen. Walker Keith Armistead. Armistead immediately went on the offensive, actively campaigning during the summer. Seeking hidden camps, the Army also burned fields and drove off livestock: horses, cattle and pigs. By the middle of the summer, the Army had destroyed 500 acres (2.0 km2) of Seminole crops.[124][125]

The Navy sent its sailors and Marines up rivers and streams, and into the Everglades. In late 1839 Navy Lt. John T. McLaughlin was given command of a joint Army-Navy amphibious force to operate in Florida. McLaughlin established his base at Tea Table Key in the upper Florida Keys. Traveling from December 1840 to the middle of January 1841, McLaughlin's force crossed the Everglades from east to west in dugout canoes, the first group of whites to complete a crossing.[126][127] The Seminoles kept out of their way.

Indian Key

Indian Key is a small island in the upper Florida Keys. In 1840, it was the county seat of the newly created Dade County, and a wrecking port. Early in the morning of August 7, 1840, a large party of "Spanish" Indians snuck onto Indian Key. By chance, one man was up and raised the alarm after spotting the Indians. Of about fifty people living on the island, forty were able to escape. The dead included Dr. Henry Perrine, former United States Consul in Campeche, Mexico, who was waiting at Indian Key until it was safe to take up a 36-square mile (93 km2) grant on the mainland that Congress had awarded to him.

The naval base on the Key was manned by a doctor, his patients, and five sailors under a midshipman. They mounted a couple of cannons on barges to attack the Indians. The Indians fired back at the sailors with musket balls loaded in cannon on the shore. The recoil of the cannon broke them loose from the barges, sending them into the water, and the sailors had to retreat. The Indians looted and burned the buildings on Indian Key. In December 1840, Col. Harney at the head of ninety men found Chakaika's camp deep in the Everglades. His force killed the chief and hanged some of the men in his band.[128][129][130]

War winds down

Armistead received US$55,000 to use for bribing chiefs to surrender. Echo Emathla, a Tallahassee chief, surrendered, but most of the Tallahassee, under Tiger Tail, did not. Coosa Tustenuggee finally accepted US$5,000 for bringing in his 60 people. Lesser chiefs received US$200, and every warrior got US$30 and a rifle. By the spring of 1841, Armistead had sent 450 Seminoles west. Another 236 were at Fort Brooke awaiting transportation. Armistead estimated that 120 warriors had been shipped west during his tenure and that no more than 300 warriors remained in Florida.[131]

In May 1841, Armistead was replaced by Col. William Jenkins Worth as commander of Army forces in Florida. Worth had to cut back on the unpopular war: he released nearly 1,000 civilian employees and consolidated commands. Worth ordered his men out on "search and destroy" missions during the summer and drove the Seminoles out of much of northern Florida.[132]

The Army's actions became a war of attrition; some Seminole surrendered to avoid starvation. Others were seized when they came in to negotiate surrender, including, for the second time, Coacoochee. A large bribe secured Coacoochee's cooperation in persuading others to surrender.[133][134]

In the last action of the war, General William Bailey and prominent planter Jack Bellamy led a posse of 52 men on a three-day pursuit of a small band of Tiger Tail's braves who had been attacking settlers, surprising their swampy encampment and killing all 24. William Wesley Hankins, at sixteen the youngest of the posse, accounted for the last of the kills and was acknowledged as having fired the last shot of the Second Seminole War.[135]

After Colonel Worth recommended early in 1842 that the remaining Seminoles be left in peace, he received authorization to leave the remaining Seminoles on an informal reservation in southwestern Florida and to declare an end to the war.,[136] He announced it on August 14, 1842. In the same month, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act, which provided free land to settlers who improved the land and were prepared to defend themselves from Indians. At the end of 1842, the remaining Indians in Florida living outside the reservation in southwest Florida were rounded up and shipped west. By April 1843, the Army presence in Florida had been reduced to one regiment. By November 1843, Worth reported that only about 95 Seminole men and some 200 women and children living on the reservation were left, and that they were no longer a threat.[137]

Aftermath

The Second Seminole War may have cost as much as $40,000,000. More than 40,000 regular U.S. military, militiamen and volunteers served in the war. This Indian war cost the lives of 1,500 soldiers, mostly from disease. It is estimated that more than 300 regular U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps personnel were killed in action, along with 55 volunteers.[138] There is no record of the number of Seminole killed in action, but many homes and Indian lives were lost. A great many Seminole died of disease or starvation in Florida, on the journey west, and after they reached Indian Territory. An unknown but apparently substantial number of white civilians were killed by Seminole during the war.[139]

Second Interbellum

Peace had come to Florida. The Indians were mostly staying on the reservation. Groups of ten or so men would visit Tampa to trade. Squatters were moving closer to the reservation, however, and in 1845 President James Polk established a 20-mile (32 km) wide buffer zone around the reservation. No land could be claimed within the buffer zone, no title would be issued for land there, and the U.S. Marshal would remove squatters from the buffer zone upon request. In 1845, Thomas P. Kennedy, who operated a store at Fort Brooke, converted his fishing station on Pine Island into a trading post for the Indians. The post did not do well, however, because whites who sold whiskey to the Indians told them that they would be seized and sent west if they went to Kennedy's store.[140]

The Florida authorities continued to press for removal of all Indians from Florida. The Indians for their part tried to limit their contacts with whites as much as possible. In 1846, Captain John T. Sprague was placed in charge of Indian affairs in Florida. He had great difficulty in getting the chiefs to meet with him. They were very distrustful of the Army since it had often seized chiefs while under a flag of truce. He did manage to meet with all of the chiefs in 1847, while investigating a report of a raid on a farm. He reported that the Indians in Florida then consisted of 120 warriors, including seventy Seminoles in Billy Bowlegs' band, thirty Mikasukis in Sam Jones' band, twelve Creeks (Muscogee speakers) in Chipco's band, 4 Yuchis and 4 Choctaws. He also estimated that there were 100 women and 140 children.[141]

Indian attacks