Effects of the storage conditions on the stability of natural and synthetic cannabis in biological matrices for forensic toxicology analysis: An update from the literature

Contents

The list of organisms by chromosome count describes ploidy or numbers of chromosomes in the cells of various plants, animals, protists, and other living organisms. This number, along with the visual appearance of the chromosome, is known as the karyotype,[1][2][3] and can be found by looking at the chromosomes through a microscope. Attention is paid to their length, the position of the centromeres, banding pattern, any differences between the sex chromosomes, and any other physical characteristics.[4] The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytogenetics.

| S. No. | Organism (B SULLAR) |

Chromosome number | Picture | Karyotype | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jack jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula) |

2/1 |  |

2 for females, males are haploid and thus have 1; smallest number possible. Other ant species have more chromosomes.[5] | [5] | |

| 2 | Spider mite (Tetranychidae) |

4–14 |  |

Spider mites (family Tetranychidae) are typically haplodiploid (males are haploid, while females are diploid)[6] | [6] | |

| 3 | Cricotopus sylvestris | 4 |  |

[7] | ||

| 4 | Oikopleura dioica | 6 |  |

[8] | ||

| 5 | Yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) |

6 |  |

|

The 2n=6 chromosome number is conserved in the entire family Culicidae, except in Chagasia bathana, which has 2n=8.[9] | [9] |

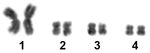

| 6 | Indian muntjac (Muntiacus muntjak) |

6/7 |  |

|

2n = 6 for females and 7 for males. The lowest diploid chromosomal number in mammals.[10] | [11] |

| 7 | Hieracium | 8 |  |

|||

| 8 | Fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) |

8 |  |

|

6 autosomal and 2 allosomic (sex) | [12] |

| 9 | Macrostomum lignano | 8 |

|

[13] | ||

| 10 | Marchantia polymorpha | 9 |  |

|

Typically haploid with dominant gametophyte stage. 8 autosomes and 1 allosome (sex chromosome). The sex-determination system used by this species and most other bryophytes is called UV. Spores can carry either the U chromosome, which results in female gametophytes, or the V chromosome, which results in males. The chromosome number n = 9 is the basic number in many species of Marchantiales. In some species of Marchantiales, plants with various ploidy levels (having 18 or 27 chromosomes) were reported, but this is rare in nature. | [14] |

| 11 | Thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) |

10 |  |

|

||

| 12 | Swamp wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) |

10/11 |  |

|

11 for male, 10 for female | [15] |

| 13 | Australian daisy (Brachyscome dichromosomatica) |

12 |  |

This species can have more B chromosomes than A chromosomes at times, but 2n=4. | [16] | |

| 14 | Nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans) |

12/11 |

|

12 for hermaphrodites, 11 for males | ||

| 15 | Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) |

12 |  |

|

[17] | |

| 16 | Broad bean (Vicia faba) |

12 |  |

|

[18] | |

| 17 | Yellow dung fly (Scathophaga stercoraria) |

12 |  |

|

10 autosomal and 2 allosomic (sex) chromosomes. Males have XY sex chromosomes and females have XX sex chromosomes. The sex chromosomes are the largest chromosomes and constitute 30% of the total length of the diploid set in females and about 25% in males.[19] | [19] |

| 18 | Slime mold (Dictyostelium discoideum) |

12 |  |

[20] | ||

| 19 | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) |

14 |  |

[21] | ||

| 20 | Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) |

14 |  |

|

||

| 21 | Rye (Secale cereale) |

14 |  |

[22] | ||

| 22 | Pea (Pisum sativum) |

14 |  |

|

[22] | |

| 23 | Barley (Hordeum vulgare) |

14 |  |

|

[23] | |

| 24 | Aloe vera | 14 |  |

|

The diploid chromosome number is 2n = 14 with four pair of long acrocentric chromosomes ranging from 14.4 μm to 17.9 μm and three pair of short sub metacentric chromosomes ranging from 4.6 μm to 5.4 μm.[24] | [24] |

| 25 | Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) |

16 |  |

|||

| 26 | Kangaroo | 16 |  |

This includes several members of genus Macropus, but not the red kangaroo (M. rufus, 20) | [25] | |

| 27 | Botryllus schlosseri | 16 |  |

[26] | ||

| 28 | Schistosoma mansoni | 16 |  |

|

2n=16. 7 autosomal pairs and ZW sex-determination pair.[27] | [27] |

| 29 | Welsh onion (Allium fistulosum) |

16 |  |

|

[28] | |

| 30 | Garlic (Allium sativum) |

16 |  |

|

[28] | |

| 31 | Itch mite (Sarcoptes scabiei) |

17/18 |  |

|

According to the observation of embryonic cells of egg, chromosome number of the itch mite is either 17 or 18. While the cause for the disparate numbers is unknown, it may arise because of an XO sex determination mechanism, where males (2n=17) lack the sex chromosome and therefore have one less chromosome than the female (2n=18).[29] | [29] |

| 32 | Radish (Raphanus sativus) |

18 |  |

[22] | ||

| 33 | Carrot (Daucus carota) |

18 |  |

|

The genus Daucus includes around 25 species. D. carota has nine chromosome pairs (2n = 2x = 18). D. capillifolius, D. sahariensis and D. syrticus are the other members of the genus with 2n = 18, whereas D. muricatus (2n = 20) and D. pusillus (2n = 22) have a slightly higher chromosome number. A few polyploid species as for example D. glochidiatus (2n = 4x = 44) and D. montanus (2n = 6x = 66) also exist.[30] | [30] |

| 34 | Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) |

18 |  |

|

Broccoli, cabbage, kale, kohlrabi, brussels sprouts, and cauliflower are all the same species and have the same chromosome number.[22] | [22] |

| 35 | Citrus (Citrus) |

18 |  |

Chromosome number of the genus Citrus, which including lemons, oranges, grapefruit, pomelo and limes, is 2n = 18.[31] | [32] | |

| 36 | Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) |

18 | [33] | |||

| 37 | Setaria viridis (Setaria viridis) |

18 |  |

[34] | ||

| 38 | Maize (Zea mays) |

20 |  |

[22] | ||

| 39 | Cannabis (Cannabis sativa) |

20 |  |

|||

| 40 | Western clawed frog (Xenopus tropicalis) |

20 |  |

|

[35] | |

| 41 | Australian pitcher plant (Cephalotus follicularis) |

20 |  |

[36] | ||

| 42 | Cacao (Theobroma cacao) |

20 |  |

|

[37] | |

| 43 | Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus) |

22 |  |

Although some contradictory cases have been reported, the large homogeneity of the chromosome number 2n = 22 is now known for 135 (33.5%) distinct species among genus Eucalyptus.[38] | [39] | |

| 44 | Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana) |

22 |

|

[40] | ||

| 45 | Bean (Phaseolus sp.) |

22 |  |

|

All species in the genus Phaseolus have the same chromosome number, including common bean (P. vulgaris), runner bean (P. coccineus), tepary bean (P. acutifolius) and lima bean (P. lunatus).[22] | [22] |

| 46 | Snail | 24 |  |

|||

| 47 | Melon (Cucumis melo) |

24 |  |

|

[41] | |

| 48 | Rice (Oryza sativa) |

24 |  |

|

[22] | |

| 49 | Silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium) |

24 |  |

[42] | ||

| 50 | Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) |

24 |  |

|

[43] | |

| 51 | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

24 |  |

|

[44] | |

| 52 | European beech (Fagus sylvatica) |

24 |  |

|

[45] | |

| 53 | Bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara) |

24 |  |

[46][47] | ||

| 54 | Cork oak (Quercus suber) |

24 |  |

|

[48] | |

| 55 | Edible frog (Pelophylax kl. esculentus) |

26 |  |

|

Edible frog is the fertile hybrid of the pool frog and the marsh frog.[49] | [50] |

| 56 | Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) |

28 |  |

|

[51] | |

| 57 | Bed bug (Cimex lectularius) |

29–47 |  |

26 autosomes and varying number of the sex chromosomes from three (X1X2Y) to 21 (X1X2Y+18 extra Xs).[52] | [52] | |

| 58 | Pill millipede (Arthrosphaera magna attems) |

30 |  |

[53] | ||

| 59 | Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) |

30 |  |

|

[54] | |

| 60 | American mink (Neogale vison) |

30 |  |

|||

| 61 | Pistachio (Pistacia vera) |

30 |  |

[55] | ||

| 62 | Japanese oak silkmoth (Antheraea yamamai) | 31 |

|

|

[56] | |

| 63 | Baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) |

32 |  |

|||

| 64 | European honey bee (Apis mellifera) |

32/16 |  |

|

32 for females (2n = 32), males are haploid and thus have 16 (1n =16).[57] | [57] |

| 65 | American badger (Taxidea taxus) |

32 |  |

|||

| 66 | Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) |

32 |  |

|

Cultivated alfalfa is tetraploid, with 2n=4x=32. Wild relatives have 2n=16.[22]: 165 | [22] |

| 67 | Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) |

34 |  |

Plus 0-8 B chromosomes. | [58] | |

| 68 | Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) |

34 |  |

|

[59] | |

| 69 | Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) |

34 |  |

[60] | ||

| 70 | Globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus) |

34 |  |

|

[61] | |

| 71 | Yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata) |

36 |  |

|||

| 72 | Tibetan sand fox (Vulpes ferrilata) |

36 |  |

|||

| 73 | Starfish (Asteroidea) |

36 |  |

|||

| 74 | Red panda (Ailurus fulgens) |

36 |  |

|||

| 75 | Meerkat (Suricata suricatta) |

36 |  |

|||

| 76 | Cassava (Manihot esculenta) |

36 |

|

[62] | ||

| 77 | Long-nosed cusimanse (Crossarchus obscurus) |

36 |  |

|||

| 78 | Earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris) |

36 |  |

|||

| 79 | African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) |

36 |  |

|

[35] | |

| 80 | Waterwheel plant (Aldrovanda vesiculosa) |

38 |  |

[36] | ||

| 81 | Tiger (Panthera tigris) |

38 |  |

|

||

| 82 | Sea otter (Enhydra lutris) |

38 |  |

|||

| 83 | Sable (Martes zibellina) |

38 | ||||

| 84 | Raccoon (Procyon lotor) |

38 |  |

[63] | ||

| 85 | Pine marten (Martes martes) |

38 |  |

|||

| 86 | Pig (Sus) |

38 |  |

|

||

| 87 | Oriental small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinerea) |

38 |  |

|||

| 88 | Lion (Panthera leo) |

38 |  |

|||

| 89 | Fisher (Pekania pennanti) |

38 |  |

a type of marten | ||

| 90 | European mink (Mustela lutreola) |

38 |  |

|||

| 91 | Coatimundi | 38 |  |

|||

| 92 | Cat (Felis catus) |

38 |  |

|

||

| 93 | Beech marten (Martes foina) |

38 |  |

|||

| 94 | Baja California rat snake (Bogertophis rosaliae) |

38 |  |

[64] | ||

| 95 | American marten (Martes americana) |

38 |  |

|||

| 96 | Trans-Pecos ratsnake (Bogertophis subocularis) |

40 |  |

[65] | ||

| 97 | Mouse (Mus musculus) |

40 |  |

|

[66] | |

| 98 | Mango (Mangifera indica) |

40 |  |

[22] | ||

| 99 | Hyena (Hyaenidae) |

40 |  |

|||

| 100 | Ferret (Mustela furo) |

40 |  |

|||

| 101 | European polecat (Mustela putorius) |

40 |  |

|||

| 102 | American beaver (Castor canadensis) |

40 |  |

|||

| 103 | Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) |

40 |  |

|

Cultivated peanut is an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 40). Its closest relatives are the diploid (2n = 2x = 20).[67] | [67] |

| 104 | Wolverine (Gulo gulo) |

42 |  |

|||

| 105 | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) |

42 |  |

|

This is a hexaploid with 2n=6x=42. Durum wheat is Triticum turgidum var. durum, and is a tetraploid with 2n=4x=28.[22] | [22] |

| 106 | Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) |

42 |  |

|

[68] | |

| 107 | Rat (Rattus norvegicus) |

42 |  |

|

[69] | |

| 108 | Oats (Avena sativa) |

42 |  |

|

This is a hexaploid with 2n=6x=42. Diploid and tetraploid cultivated species also exist.[22] | [22] |

| 109 | Giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) |

42 |  |

|||

| 110 | Fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox) |

42 |  |

|||

| 111 | European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) |

44 |  |

|

||

| 112 | Eurasian badger (Meles meles) |

44 |  |

|||

| 113 | Moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) |

44 |  |

[70] | ||

| 114 | Dolphin (Delphinidae) |

44 |  |

|||

| 115 | Arabian coffee (Coffea arabica) |

44 |  |

|

Out of the 103 species in the genus Coffea, arabica coffee is the only tetraploid species (2n = 4x = 44), the remaining species being diploid with 2n = 2x = 22.[71] | |

| 116 | Reeves's muntjac (Muntiacus reevesi) |

46 |  |

|||

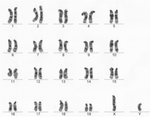

| 117 | Human (Homo sapiens) |

46 |  |

|

44 autosomal. and 2 allosomic (sex) | [72] |

| 118 | Olive

(Olea Europaea) |

46 |

|

|||

| 119 | Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) |

46 |

|

[73] | ||

| 120 | Parhyale hawaiensis | 46 |  |

|

[74] | |

| 121 | Water buffalo (swamp type) (Bubalus bubalis) |

48 |  |

|||

| 122 | Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) |

48 |  |

|

Cultivated species N. tabacum is an amphidiploid (2n=4x=48) evolved through the interspecific hybridization of the ancestors of N. sylvestris (2n=2x=24, maternal donor) and N. tomentosiformis (2n=2x=24, paternal donor) about 200,000 years ago.[75] | [75] |

| 123 | Potato (Solanum tuberosum) |

48 |  |

|

This is for common potato Solanum tuberosum (tetraploid, 2n = 4x = 48). Other cultivated potato species may be diploid (2n = 2x = 24), triploid (2n = 3x = 36), tetraploid (2n = 4x = 48), or pentaploid (2n = 5x = 60).[76] Wild relatives mostly have 2n=24.[22] | [76] |

| 124 | Orangutan (Pongo) |

48 |  |

|

||

| 125 | Hare (Lepus) |

48 |  |

[77][78] | ||

| 126 | Gorilla (Gorilla) |

48 |  |

|||

| 127 | Deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) |

48 |  |

|||

| 128 | Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) |

48 |  |

|

[79] | |

| 129 | Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) |

48 |  |

|||

| 130 | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) |

50 |

|

[80] | ||

| 131 | Woodland hedgehogs Erinaceus |

48 |  |

[81] | ||

| 132 | African hedgehogs Atelerix |

48 |  |

[82] | ||

| 133 | Water buffalo (Riverine type) (Bubalus bubalis) |

50 |  |

|

||

| 134 | Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis) |

50 |  |

|||

| 135 | Pineapple (Ananas comosus) |

50 |  |

[22] | ||

| 136 | Kit fox (Vulpes macrotis) |

50 |  |

|||

| 137 | Spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) |

52 |  |

|||

| 138 | Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) |

52 |  |

|

Ten sex chromosomes. Males have X1Y1X2Y2X3Y3X4Y4X5Y5, females have X1X1X2X2X3X3X4X4X5X5.[83] | [84] |

| 139 | Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) |

52 |  |

|

This is for the cultivated species G. hirsutum (allotetraploid, 2n=4x=52). This species accounts for 90% of the world cotton production. Among 50 species in the genus Gossypium, 45 are diploid (2n = 2x = 26) and 5 are allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 52).[85] | [85] |

| 140 | Sheep (Ovis aries) |

54 |  |

|

||

| 141 | Hyrax (Hyracoidea) |

54 |  |

|

Hyraxes were considered to be the closest living relatives of elephants,[86] but sirenians have been found to be more closely related to elephants. | [87] |

| 142 | Raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides procyonoides) |

54 |  |

|

This number is for common raccoon dog (N. p. procyonoides), 2n=54+B(0–4). On the other hand, Japanese raccoon dog (N. p. viverrinus) with 2n=38+B(0–8). Here, B represents B chromosome and its variation in the number between individuals.[88][89] | [88] |

| 143 | Capuchin monkey (Cebinae) |

54 |  |

[90] | ||

| 144 | Silkworm (Bombyx mori) |

56 |  |

|

This is for the species mulberry silkworm, B. mori (2n=56). Probably more than 99% of the world's commercial silk today come from this species.[91] Other silk producing moths, called non-mulberry silkworms, have various chromosome numbers. (e.g. Samia cynthia with 2n=25–28,[92] Antheraea pernyi with 2n=98.[93]) | [94] |

| 145 | Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

56 |  |

|

This number is octoploid, main cultivated species Fragaria × ananassa (2n = 8x = 56). In genus Fragaria, basic chromosome number is seven (x = 7) and multiple levels of ploidy, ranging from diploid (2n = 2x = 14) to decaploid (F. iturupensis, 2n = 10x = 70), are known.[95] | [95] |

| 146 | Gaur (Bos gaurus) |

56 |  |

|||

| 147 | Elephant (Elephantidae) |

56 |  |

|||

| 148 | †Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) |

58 |  |

extinct; tissue from a frozen carcass | ||

| 149 | Domestic yak (Bos grunniens) |

60 |  |

|||

| 150 | Goat (Capra hircus) |

60 |  |

|

||

| 151 | Cattle (Bos taurus) |

60 |  |

|

||

| 152 | American bison (Bison bison) |

60 |  |

|||

| 153 | Sable antelope (Hippotragus niger) |

60 |  |

[96] | ||

| 154 | Bengal fox (Vulpes bengalensis) |

60 |  |

|||

| 155 | Gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) |

62 |  |

|||

| 156 | Donkey (Equus asinus) |

62 |  |

|||

| 157 | Scarlet macaw (Ara macao) |

62–64 |  |

|

[97] | |

| 158 | Mule | 63 |  |

semi-infertile (odd number of chromosomes – between donkey (62) and horse (64) makes meiosis much more difficult) | ||

| 159 | Guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) |

64 |  |

|

||

| 160 | Spotted skunk (Spilogale x) |

64 |  |

|||

| 161 | Horse (Equus caballus) |

64 |  |

|

||

| 162 | Fennec fox (Vulpes zerda) |

64 |  |

[98] | ||

| 163 | Echidna (Tachyglossidae) |

63/64 |  |

63 (X1Y1X2Y2X3Y3X4Y4X5, male) and 64 (X1X1X2X2X3X3X4X4X5X5, female)[99] | ||

| 164 | Chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) |

64 |  |

[60] | ||

| 165 | Nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) |

64 |  |

|

[100] | |

| 166 | Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) |

66 |  |

[98] | ||

| 167 | Red deer (Cervus elaphus) |

68 |  |

|||

| 168 | Elk (wapiti) (Cervus canadensis) |

68 |  |

|||

| 169 | Roadside hawk (Rupornis magnirostris) |

68 |  |

[101] | ||

| 170 | White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) |

70 |  |

|||

| 171 | Black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) |

72 |  |

[102] | ||

| 172 | Tropical blue bamboo (Bambusa chungii) |

64–72 |  |

[103] | ||

| 173 | Bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis) |

72 |  |

[98] | ||

| 174 | Sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) |

74 |  |

|||

| 175 | Sloth bear (Melursus ursinus) |

74 |  |

|||

| 176 | Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) |

74 |  |

|||

| 177 | Brown bear (Ursus arctos) |

74 |  |

|||

| 178 | Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus) |

74 |  |

|||

| 179 | American black bear (Ursus americanus) |

74 |  |

|||

| 180 | Bush dog (Speothos venaticus) |

74 |  |

|||

| 181 | Maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) |

76 |  |

|||

| 182 | Gray wolf (Canis lupus) |

78 |  |

|||

| 183 | Golden jackal (Canis aureus) |

78 |  |

[98] | ||

| 184 | Dove (Columbidae) |

78 |  |

Based on African collared dove | [104] | |

| 185 | Dog (Canis familiaris) |

78 |  |

|

Normal dog karyotype is composed of 38 pairs of acrocentric autosomes and two metacentric sex chromosomes.[105][106] | [107] |

| 186 | Dingo (Canis familiaris) |

78 |  |

[98] | ||

| 187 | Dhole (Cuon alpinus) |

78 |  |

|||

| 188 | Coyote (Canis latrans) |

78 |  |

[98] | ||

| 189 | Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) |

78 |  |

|||

| 190 | African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) |

78 |  |

[98] | ||

| 191 | Tropical pitcher plant (Nepenthes rafflesiana) |

78 |  |

[36] | ||

| 192 | Turkey (Meleagris) |

80 |  |

[108] | ||

| 193 | Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) |

80 |  |

|

This is for S. officinarum (octoploid, 2n = 8× = 80).[109] About 70% of the world's sugar comes from this species.[110] Other species in the genus Saccharum, collectively known as sugarcane, have chromosome numbers in the range 2n=40–128.[111] | [109] |

| 194 | Pigeon (Columbidae) |

80 |  |

[112] | ||

| 195 | Azure-winged magpie (Cyanopica cyanus) |

80 |

|

[113] | ||

| 196 | Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) |

82 |  |

[114] | ||

| 197 | Bloody crane's-bill (Geranium sanguineum) |

84 |  |

[115] | ||

| 198 | Moonworts (Botrychium) |

90 |  |

|||

| 199 | Grape fern (Sceptridium) |

90 |  |

|||

| 200 | Pittier's crab-eating rat (Ichthyomys pittieri) |

92 |  |

Previously thought to be the highest number in mammals, tied with Anotomys leander. | [116] | |

| 201 | Prawn (Penaeus semisulcatus) |

86–92 |  |

[117] | ||

| 202 | Aquatic rat (Anotomys leander) |

92 |  |

Previously thought to be the highest number in mammals, tied with Ichthyomys pittieri. | [116] | |

| 203 | Kamraj (fern) (Helminthostachys zeylanica) |

94 |  |

|||

| 204 | Crucian carp (Carassius carassius) |

100 |  |

|

[118] | |

| 205 | Red viscacha rat (Tympanoctomys barrerae) |

102 |  |

|

Highest number known in mammals, thought to be a tetraploid[119] or allotetraploid.[120] | [121] |

| 206 | Walking catfish (Clarias batrachus) |

104 |  |

|

[122] | |

| 207 | American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula) |

120 |  |

[123] | ||

| 208 | Limestone fern (Gymnocarpium robertianum) |

160 |  |

Tetraploid (2n = 4x = 160) | [124] | |

| 209 | African baobab (Adansonia digitata) |

168 |  |

Also known as the "tree of life". 2n = 4x = 168 | [125] | |

| 210 | Northern lampreys (Petromyzontidae) |

174 |  |

[126] | ||

| 211 | Rattlesnake fern (Botrypus virginianus) |

184 |  |

[127] | ||

| 212 | Red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus) |

208 |  |

|||

| 213 | Field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) |

216 |  |

|||

| 214 | Agrodiaetus butterfly (Agrodiaetus shahrami) |

268 |  |

This insect has one of the highest chromosome numbers among all animals. | [128] | |

| 215 | Black mulberry (Morus nigra) |

308 |  |

Highest ploidy among plants, 22-ploid (2n = 22x = 308)[129] | [130] | |

| 216 | Atlas blue (Polyommatus atlantica) |

448–452 |  |

|

2n = c. 448–452. Highest number of chromosomes in the non-polyploid eukaryotic organisms.[131] | [131] |

| 217 | Adders-tongue (Ophioglossum reticulatum) |

1260 |  |

n=120–720 with a high degree of polyploidization.[132] Ophioglossum reticulatum n=720 in hexaploid species, 2n=1260 in decaploid species.[133] | ||

| 218 | Ciliated protozoa (Tetrahymena thermophila) |

10 (in micronucleus) |  |

50x = 12,500 (in macronucleus, except minichromosomes) 10,000x = 10,000 (macronuclear minichromosomes)[134] |

||

| 219 | Ciliated protozoa (Sterkiella histriomuscorum) |

16000[135] |  |

Macronuclear "nanochromosomes"; ampliploid. MAC chromosomes × 1900 ploidy level = 2.964 × 107 chromosomes | [136][137][138] |

-

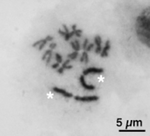

Karyotype of a human being. It shows 22 homologous autosomal chromosome pairs, both the female (XX) and male (XY) versions of the two sex chromosomes, as well as the mitochondrial genome (at bottom left).

-

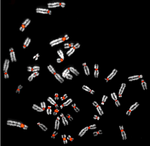

Fusion of ancestral chromosomes left distinctive remnants of telomeres, and a vestigial centromere. As other non-human extant hominidae have 48 chromosomes it is believed that the human chromosome 2 is the result of the merging of two chromosomes.[139]

References

- ^ Concise Oxford Dictionary

- ^ White MJ (1973). The chromosomes (6th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. p. 28.

- ^ Stebbins GL (1950). "Chapter XII: The Karyotype". Variation and evolution in plants. Columbia University Press.

- ^ King RC, Stansfield WD, Mulligan PK (2006). A dictionary of genetics (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 242.

- ^ a b Crosland MW, Crozier RH (March 1986). "Myrmecia pilosula, an Ant with Only One Pair of Chromosomes". Science. 231 (4743): 1278. Bibcode:1986Sci...231.1278C. doi:10.1126/science.231.4743.1278. PMID 17839565. S2CID 25465053.

- ^ a b Helle W, Bolland HR, Gutierrez J (1972). "Minimal chromosome number in false spider mites (Tenuipalpidae)". Experientia. 28 (6): 707. doi:10.1007/BF01944992. S2CID 29547273.

- ^ Michailova P (1976). "Cytotaxonomical Diagnostics of Species from the Genus Cricotopus (Chironomidae, Diptera)". Caryologia. 29 (3): 291–306. doi:10.1080/00087114.1976.10796669.

- ^ Körner WH (1952). "Untersuchungen über die Gehäusebildung bei Appendicularien (Oikopleura dioica Fol)". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Ökologie der Tiere. 41 (1): 1–53. doi:10.1007/BF00407623. JSTOR 43261846. S2CID 19101198.

- ^ a b Giannelli F, Hall JC, Dunlap JC, Friedmann T (1999). Advances in Genetics, Volume 41 (Advances in Genetics). Boston: Academic Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-12-017641-0.

- ^ Wang W, Lan H (September 2000). "Rapid and parallel chromosomal number reductions in muntjac deer inferred from mitochondrial DNA phylogeny". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 17 (9): 1326–33. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026416. PMID 10958849.

- ^ Wurster DH, Benirschke K (June 1970). "Indian muntjac, Muntiacus muntjak: a deer with a low diploid chromosome number". Science. 168 (3937): 1364–6. Bibcode:1970Sci...168.1364W. doi:10.1126/science.168.3937.1364. PMID 5444269. S2CID 45371297.

- ^ "Drosophila Genome Project". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ^ Zadesenets KS, Vizoso DB, Schlatter A, Konopatskaia ID, Berezikov E, Schärer L, Rubtsov NB (2016). "Evidence for Karyotype Polymorphism in the Free-Living Flatworm, Macrostomum lignano, a Model Organism for Evolutionary and Developmental Biology". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0164915. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1164915Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164915. PMC 5068713. PMID 27755577.

- ^ Shimamura, Masaki (2016). "Marchantia polymorpha: Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Morphology of a Model System". Plant & Cell Physiology. 57 (2): 230–256. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcv192. PMID 26657892.

- ^ Toder R, O'Neill RJ, Wienberg J, O'Brien PC, Voullaire L, Marshall-Graves JA (June 1997). "Comparative chromosome painting between two marsupials: origins of an XX/XY1Y2 sex chromosome system". Mammalian Genome. 8 (6): 418–22. doi:10.1007/s003359900459. PMID 9166586. S2CID 12515691.

- ^ Leach CR, Donald TM, Franks TK, Spiniello SS, Hanrahan CF, Timmis JN (July 1995). "Organisation and origin of a B chromosome centromeric sequence from Brachycome dichromosomatica". Chromosoma. 103 (10): 708–14. doi:10.1007/BF00344232. PMID 7664618. S2CID 12246995.

- ^ Fujito S, Takahata S, Suzuki R, Hoshino Y, Ohmido N, Onodera Y (June 2015). "Evidence for a Common Origin of Homomorphic and Heteromorphic Sex Chromosomes in Distinct Spinacia Species". G3. 5 (8): 1663–73. doi:10.1534/g3.115.018671. PMC 4528323. PMID 26048564.

- ^ Patlolla AK, Berry A, May L, Tchounwou PB (May 2012). "Genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in Vicia faba: a pilot study on the environmental monitoring of nanoparticles". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 9 (5): 1649–62. doi:10.3390/ijerph9051649. PMC 3386578. PMID 22754463.

- ^ a b Sbilordo SH, Martin OY, Ward PI (2010). "The karyotype of the yellow dung fly, Scathophaga stercoraria, a model organism in studies of sexual selection". Journal of Insect Science. 10 (118): 1–11. doi:10.1673/031.010.11801. PMC 3016996. PMID 20874599.

- ^ "First of six chromosomes sequenced in Dictyostelium discoideum". Genome News Network. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ^ Zhang Y, Cheng C, Li J, Yang S, Wang Y, Li Z, et al. (September 2015). "Chromosomal structures and repetitive sequences divergence in Cucumis species revealed by comparative cytogenetic mapping". BMC Genomics. 16 (1): 730. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1877-6. PMC 4583154. PMID 26407707.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Simmonds, NW, ed. (1976). Evolution of crop plants. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-44496-6.[page needed]

- ^ Schubert V, Ruban A, Houben A (2016). "Chromatin Ring Formation at Plant Centromeres". Frontiers in Plant Science. 7: 28. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00028. PMC 4753331. PMID 26913037.

- ^ a b Haque SM, Ghosh B (December 2013). "High frequency microcloning of Aloe vera and their true-to-type conformity by molecular cytogenetic assessment of two years old field growing regenerated plants". Botanical Studies. 54 (1): 46. Bibcode:2013BotSt..54...46H. doi:10.1186/1999-3110-54-46. PMC 5430365. PMID 28510900.

- ^ Rofe RH (December 1978). "G-banded chromosomes and the evolution of macropodidae". Australian Mammalogy. 2: 50–63. doi:10.1071/AM78007. ISSN 0310-0049. S2CID 254728517.

- ^ Colombera D (1974). "Chromosome number within the class Ascidiacea". Marine Biology. 26 (1): 63–68. Bibcode:1974MarBi..26...63C. doi:10.1007/BF00389087. S2CID 84189212.

- ^ a b Berriman M, Haas BJ, LoVerde PT, Wilson RA, Dillon GP, Cerqueira GC, et al. (July 2009). "The genome of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni". Nature. 460 (7253): 352–8. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..352B. doi:10.1038/nature08160. PMC 2756445. PMID 19606141.

- ^ a b Nagaki K, Yamamoto M, Yamaji N, Mukai Y, Murata M (2012). "Chromosome dynamics visualized with an anti-centromeric histone H3 antibody in Allium". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e51315. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751315N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051315. PMC 3517398. PMID 23236469.

- ^ a b Mounsey KE, Willis C, Burgess ST, Holt DC, McCarthy J, Fischer K (January 2012). "Quantitative PCR-based genome size estimation of the astigmatid mites Sarcoptes scabiei, Psoroptes ovis and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus". Parasites & Vectors. 5: 3. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-3. PMC 3274472. PMID 22214472.

- ^ a b Dunemann F, Schrader O, Budahn H, Houben A (2014). "Characterization of centromeric histone H3 (CENH3) variants in cultivated and wild carrots (Daucus sp.)". PLOS ONE. 9 (6): e98504. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...998504D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098504. PMC 4041860. PMID 24887084.

- ^ Guerra M, Pedrosa A, Cornélio MT, Santos K, Soares Filho WD (1997). "Chromosome number and secondary constriction variation in 51 accessions of a citrus germplasm bank". Brazilian Journal of Genetics. 20 (3): 489–496. doi:10.1590/S0100-84551997000300021.

- ^ Hynniewta M, Malik SK, Rao SR (2011). "Karyological studies in ten species of Citrus(Linnaeus, 1753) (Rutaceae) of North-East India". Comparative Cytogenetics. 5 (4): 277–87. doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v5i4.1796. PMC 3833788. PMID 24260635.

- ^ Souza, Margarete Magalhães, Telma N. Santana Pereira, and Maria Lúcia Carneiro Vieira. "Cytogenetic studies in some species of Passiflora L.(Passifloraceae): a review emphasizing Brazilian species." Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 51.2 (2008): 247–258. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-89132008000200003

- ^ Nani TF, Cenzi G, Pereira DL, Davide LC, Techio VH (2015). "Ribosomal DNA in diploid and polyploid Setaria (Poaceae) species: number and distribution". Comparative Cytogenetics. 9 (4): 645–60. doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i4.5456. PMC 4698577. PMID 26753080.

- ^ a b Matsuda Y, Uno Y, Kondo M, Gilchrist MJ, Zorn AM, Rokhsar DS, et al. (April 2015). "A New Nomenclature of Xenopus laevis Chromosomes Based on the Phylogenetic Relationship to Silurana/Xenopus tropicalis". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 145 (3–4): 187–91. doi:10.1159/000381292. PMID 25871511. S2CID 207626597.

- ^ a b c Kondo K (May 1969). "Chromosome Numbers of Carnivorous Plants". Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 96 (3): 322–328. doi:10.2307/2483737. JSTOR 2483737.

- ^ da Silva RA, Souza G, Lemos LS, Lopes UV, Patrocínio NG, Alves RM, et al. (2017). "Genome size, cytogenetic data and transferability of EST-SSRs markers in wild and cultivated species of the genus Theobroma L. (Byttnerioideae, Malvaceae)". PLOS ONE. 12 (2): e0170799. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1270799D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170799. PMC 5302445. PMID 28187131.

- ^ Oudjehih B, Abdellah B (2006). "Chromosome numbers of the 59 species of Eucalyptus L'Herit. (Myrtaceae)". Caryologia. 59 (3): 207–212. doi:10.1080/00087114.2006.10797916.

- ^ Balasaravanan T, Chezhian P, Kamalakannan R, Ghosh M, Yasodha R, Varghese M, Gurumurthi K (October 2005). "Determination of inter- and intra-species genetic relationships among six Eucalyptus species based on inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR)". Tree Physiology. 25 (10): 1295–302. doi:10.1093/treephys/25.10.1295. PMID 16076778.

- ^ Biggers JD, Fritz HI, Hare WC, Mcfeely RA (June 1965). "Chromosomes of American Marsupials". Science. 148 (3677): 1602–3. Bibcode:1965Sci...148.1602B. doi:10.1126/science.148.3677.1602. PMID 14287602. S2CID 46617910.

- ^ Argyris JM, Ruiz-Herrera A, Madriz-Masis P, Sanseverino W, Morata J, Pujol M, et al. (January 2015). "Use of targeted SNP selection for an improved anchoring of the melon (Cucumis melo L.) scaffold genome assembly". BMC Genomics. 16 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s12864-014-1196-3. PMC 4316794. PMID 25612459.

- ^ Heiser CB, Whitaker TW (March 1948). "Chromosome number, polyploidy, and growth habit in California weeds". American Journal of Botany. 35 (3): 179–86. doi:10.2307/2438241. JSTOR 2438241. PMID 18909963.

- ^ Ivanova D, Vladimirov V (2007). "Chromosome numbers of some woody species from the Bulgarian flora" (PDF). Phytologia Balcanica. 13 (2): 205–207.

- ^ Staginnus C, Gregor W, Mette MF, Teo CH, Borroto-Fernández EG, Machado ML, et al. (May 2007). "Endogenous pararetroviral sequences in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and related species". BMC Plant Biology. 7: 24. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-7-24. PMC 1899175. PMID 17517142.

- ^ Packham JR, Thomas PA, Atkinson MD, Degen T (2012). "Biological Flora of the British Isles:Fagus sylvatica". Journal of Ecology. 100 (6): 1557–1608. Bibcode:2012JEcol.100.1557P. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2012.02017.x. S2CID 85095298.

- ^ Abrams L (1951). Illustrated Flora of the Pacific States. Volume 3. Stanford University Press. p. 866.

- ^ Stace C (1997). New Flora of the British Isles (Second ed.). Cambridge, UK. p. 1130.

- ^ Zaldoš V, Papeš D, Brown SC, Panaus O, Šiljak-Yakovlev S (1998) Genome size and base composition of seven Quercus species: inter- and intra-population variation. Genome, 41: 162–168.

- ^ Doležálková M, Sember A, Marec F, Ráb P, Plötner J, Choleva L (July 2016). "Is premeiotic genome elimination an exclusive mechanism for hemiclonal reproduction in hybrid males of the genus Pelophylax?". BMC Genetics. 17 (1): 100. doi:10.1186/s12863-016-0408-z. PMC 4930623. PMID 27368375.

- ^ Zaleśna A, Choleva L, Ogielska M, Rábová M, Marec F, Ráb P (2011). "Evidence for integrity of parental genomes in the diploid hybridogenetic water frog Pelophylax esculentus by genomic in situ hybridization". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 134 (3): 206–12. doi:10.1159/000327716. PMID 21555873. S2CID 452336.

- ^ Keinath MC, Timoshevskiy VA, Timoshevskaya NY, Tsonis PA, Voss SR, Smith JJ (November 2015). "Initial characterization of the large genome of the salamander Ambystoma mexicanum using shotgun and laser capture chromosome sequencing". Scientific Reports. 5: 16413. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516413K. doi:10.1038/srep16413. PMC 4639759. PMID 26553646.

- ^ a b Sadílek D, Angus RB, Šťáhlavský F, Vilímová J (2016). "Comparison of different cytogenetic methods and tissue suitability for the study of chromosomes in Cimex lectularius (Heteroptera, Cimicidae)". Comparative Cytogenetics. 10 (4): 731–752. doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i4.10681. PMC 5240521. PMID 28123691.

- ^ Achar KP (1986). "Analysis of male meiosis in seven species of Indian pill-millipede". Caryologia. 39 (39): 89–101. doi:10.1080/00087114.1986.10797770.

- ^ Huang L, Nesterenko A, Nie W, Wang J, Su W, Graphodatsky AS, Yang F (2008). "Karyotype evolution of giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) revealed by cross-species chromosome painting with Chinese muntjac (Muntiacus reevesi) and human (Homo sapiens) paints". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 122 (2): 132–8. doi:10.1159/000163090. PMID 19096208. S2CID 6674957.

- ^ Sola-Campoy PJ, Robles F, Schwarzacher T, Ruiz Rejón C, de la Herrán R, Navajas-Pérez R (2015). "The Molecular Cytogenetic Characterization of Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) Suggests the Arrest of Recombination in the Largest Heteropycnotic Pair HC1". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143861. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043861S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143861. PMC 4669136. PMID 26633808.

- ^ Kim SR, Kwak W, Kim H, Caetano-Anolles K, Kim KY, Kim SB, et al. (January 2018). "Genome sequence of the Japanese oak silk moth, Antheraea yamamai: the first draft genome in the family Saturniidae". GigaScience. 7 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1093/gigascience/gix113. PMC 5774507. PMID 29186418.

- ^ a b Gempe T, Hasselmann M, Schiøtt M, Hause G, Otte M, Beye M (October 2009). "Sex determination in honeybees: two separate mechanisms induce and maintain the female pathway". PLOS Biology. 7 (10): e1000222. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000222. PMC 2758576. PMID 19841734.

- ^ Rubtsov, Nikolai B. (1 April 1998). "The Fox Gene Map". ILAR. 39 (2–3): 182–188. doi:10.1093/ilar.39.2-3.182. PMID 11528077.

- ^ Feng J, Liu Z, Cai X, Jan CC (January 2013). "Toward a molecular cytogenetic map for cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) by landed BAC/BIBAC clones". G3. 3 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1534/g3.112.004846. PMC 3538341. PMID 23316437.

- ^ a b "Metapress – Discover More". 24 June 2016.

- ^ Giorgi D, Pandozy G, Farina A, Grosso V, Lucretti S, Gennaro A, et al. (2016). "First detailed karyo-morphological analysis and molecular cytological study of leafy cardoon and globe artichoke, two multi-use Asteraceae crops". Comparative Cytogenetics. 10 (3): 447–463. doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i3.9469. PMC 5088355. PMID 27830052.

- ^ An F, Fan J, Li J, Li QX, Li K, Zhu W, et al. (2014). "Comparison of leaf proteomes of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) cultivar NZ199 diploid and autotetraploid genotypes". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e85991. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...985991A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085991. PMC 3984080. PMID 24727655.

- ^ Perelman PL, Graphodatsky AS, Dragoo JW, Serdyukova NA, Stone G, Cavagna P, et al. (2008). "Chromosome painting shows that skunks (Mephitidae, Carnivora) have highly rearranged karyotypes". Chromosome Research. 16 (8): 1215–31. doi:10.1007/s10577-008-1270-2. PMID 19051045. S2CID 952184.

- ^ Dowling HG, Price RM (1988). "A proposed new genus for Elaphe subocularis and Elaphe rosaliae" (PDF). The Snake. 20 (1): 52–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2014.

- ^ Baker, R. J.; Bull, J. J.; Mengden, G. A. (1971). "Chromosomes ofElaphe subocularis (Reptilia: Serpentes), with the description of an in vivo technique for preparation of snake chromosomes". Experientia. 27 (10): 1228–1229. doi:10.1007/BF02286946.

- ^ The Jackson Laboratory Archived 2013-01-25 at the Wayback Machine: "Mice with chromosomal aberrations".

- ^ a b Milla SR, Isleib TG, Stalker HT (February 2005). "Taxonomic relationships among Arachis sect. Arachis species as revealed by AFLP markers". Genome. 48 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1139/g04-089. PMID 15729391.

- ^ Moore CM, Dunn BG, McMahan CA, Lane MA, Roth GS, Ingram DK, Mattison JA (March 2007). "Effects of calorie restriction on chromosomal stability in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta)". Age. 29 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1007/s11357-006-9016-6. PMC 2267682. PMID 19424827.

- ^ "Rnor_6.0 - Assembly - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Diupotex-Chong ME, Ocaña-Luna A, Sánchez-Ramírez M (July 2009). "Chromosome analysis of Linné, 1758 (Scyphozoa: Ulmaridae), southern Gulf of Mexico". Marine Biology Research. 5 (4): 399–403. doi:10.1080/17451000802534907. S2CID 84514554.

- ^ Geleta M, Herrera I, Monzón A, Bryngelsson T (2012). "Genetic diversity of arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.) in Nicaragua as estimated by simple sequence repeat markers". TheScientificWorldJournal. 2012: 939820. doi:10.1100/2012/939820. PMC 3373144. PMID 22701376.

- ^ "Human Genome Project". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ^ Gallagher, D. S.; Davis, S. K.; De Donato, M.; Burzlaff, J. D.; Womack, J. E.; Taylor, J. F.; Kumamoto, A. T. (November 1998). "A karyotypic analysis of nilgai, Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)". Chromosome Research. 6 (7): 505–513. doi:10.1023/a:1009268917856. ISSN 0967-3849. PMID 9886771. S2CID 21120780.

- ^ Kao D, Lai AG, Stamataki E, Rosic S, Konstantinides N, Jarvis E, et al. (November 2016). "The genome of the crustacean Parhyale hawaiensis, a model for animal development, regeneration, immunity and lignocellulose digestion". eLife. 5. doi:10.7554/eLife.20062. PMC 5111886. PMID 27849518.

- ^ a b Sierro N, Battey JN, Ouadi S, Bakaher N, Bovet L, Willig A, et al. (May 2014). "The tobacco genome sequence and its comparison with those of tomato and potato". Nature Communications. 5: 3833. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3833S. doi:10.1038/ncomms4833. PMC 4024737. PMID 24807620.

- ^ a b Machida-Hirano R (March 2015). "Diversity of potato genetic resources". Breeding Science. 65 (1): 26–40. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.65.26. PMC 4374561. PMID 25931978.

- ^ Robinson TJ, Yang F, Harrison WR (2002). "Chromosome painting refines the history of genome evolution in hares and rabbits (order Lagomorpha)". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 96 (1–4): 223–7. doi:10.1159/000063034. PMID 12438803. S2CID 19327437.

- ^ "4.W4". Rabbits, Hares and Pikas. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. pp. 61–94. Archived from the original on 2011-05-05.

- ^ Young WJ, Merz T, Ferguson-Smith MA, Johnston AW (June 1960). "Chromosome number of the chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes". Science. 131 (3414): 1672–3. Bibcode:1960Sci...131.1672Y. doi:10.1126/science.131.3414.1672. PMID 13846659. S2CID 36235641.

- ^ Postlethwait JH, Woods IG, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan YL, Kelly PD, Chu F, et al. (December 2000). "Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes". Genome Research. 10 (12): 1890–902. doi:10.1101/gr.164800. PMID 11116085.

- ^ Anna Grzesiakowska; Przemysław Baran,2; Marta Kuchta-Gładysz; Olga Szeleszczuk1 (2019). "Cytogenetic Karyotype Analysis in Selected Species of the Erinaceidae Family". Journal of Veterinary Research. 63 (3): 353–358. doi:10.2478/jvetres-2019-0041. PMC 6749745. PMID 31572815.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anna Grzesiakowska; Przemysław Baran; Marta Kuchta-Gładysz; Olga Szeleszczuk1 (2019). "Cytogenetic Karyotype Analysis in Selected Species of the Erinaceidae Family". Journal of Veterinary Research. 63 (3): 353–358. doi:10.2478/jvetres-2019-0041. PMC 6749745. PMID 31572815.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Brien S (2006). Atlas of mammalian chromosomes. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-471-35015-6.

- ^ Warren WC, Hillier LW, Marshall Graves JA, Birney E, Ponting CP, Grützner F, et al. (May 2008). "Genome analysis of the platypus reveals unique signatures of evolution". Nature. 453 (7192): 175–83. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..175W. doi:10.1038/nature06936. PMC 2803040. PMID 18464734.

- ^ a b Chen H, Khan MK, Zhou Z, Wang X, Cai X, Ilyas MK, et al. (December 2015). "A high-density SSR genetic map constructed from a F2 population of Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium darwinii". Gene. 574 (2): 273–86. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.022. PMID 26275937.

- ^ "Hyrax: The Little Brother of the Elephant", Wildlife on One, BBC TV.

- ^ O'Brien SJ, Meninger JC, Nash WG (2006). Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. John Wiley & sons. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-471-35015-6.

- ^ a b Mäkinen A, Kuokkanen MT, Valtonen M (1986). "A chromosome-banding study in the Finnish and the Japanese raccoon dog". Hereditas. 105 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.1986.tb00647.x. PMID 3793521.

- ^ Ostrander EA (1 January 2012). Genetics of the Dog. CABI. pp. 250–. ISBN 978-1-84593-941-0.

- ^ Barnabe RC, Guimarães MA, Oliveira CA, Barnabe AH (2002). "Analysis of some normal parameters of the spermiogram of captive capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella Linnaeus, 1758 )" (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science. 39 (6). doi:10.1590/S1413-95962002000600010.

- ^ Peigler, Richard S. (1993). "Wild Silks of the World". American Entomologist. 39 (3): 151–162. doi:10.1093/ae/39.3.151.

- ^ Yoshido A, Yasukochi Y, Sahara K (June 2011). "Samia cynthia versus Bombyx mori: comparative gene mapping between a species with a low-number karyotype and the model species of Lepidoptera" (PDF). Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 41 (6): 370–7. Bibcode:2011IBMB...41..370Y. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.02.005. hdl:2115/45607. PMID 21396446. S2CID 38794541.

- ^ Mahendran B, Ghosh SK, Kundu SC (April 2006). "Molecular phylogeny of silk-producing insects based on 16S ribosomal RNA and cytochrome oxidase subunit I genes". Journal of Genetics. 85 (1): 31–8. doi:10.1007/bf02728967. PMID 16809837. S2CID 11733404.

- ^ Yoshido A, Bando H, Yasukochi Y, Sahara K (June 2005). "The Bombyx mori karyotype and the assignment of linkage groups". Genetics. 170 (2): 675–85. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.040352. PMC 1450397. PMID 15802516.

- ^ a b Liu B, Davis TM (November 2011). "Conservation and loss of ribosomal RNA gene sites in diploid and polyploid Fragaria (Rosaceae)". BMC Plant Biology. 11: 157. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-11-157. PMC 3261831. PMID 22074487.

- ^ Claro, Françoise; Hayes, Hélène; Cribiu, Edmond Paul (November 1993). "The R- and G-Banded Karyotypes of the Sable Antelope (Hippotragus niger)". Journal of Heredity. 84 (6): 481–484. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111376. PMID 8270772. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Seabury CM, Dowd SE, Seabury PM, Raudsepp T, Brightsmith DJ, Liboriussen P, et al. (2013). "A multi-platform draft de novo genome assembly and comparative analysis for the Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao)". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e62415. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862415S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062415. PMC 3648530. PMID 23667475.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sillero-Zubiri C, Hoffmann MJ, Mech D (2004). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. World Conservation Union. ISBN 978-2-8317-0786-0.[page needed]

- ^ Rens W, O'Brien PC, Grützner F, Clarke O, Graphodatskaya D, Tsend-Ayush E, et al. (2007). "The multiple sex chromosomes of platypus and echidna are not completely identical and several share homology with the avian Z". Genome Biology. 8 (11): R243. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r243. PMC 2258203. PMID 18021405.

- ^ Svartman M, Stone G, Stanyon R (July 2006). "The ancestral eutherian karyotype is present in Xenarthra". PLOS Genetics. 2 (7): e109. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020109. PMC 1513266. PMID 16848642.

- ^ de Oliveira EH, Tagliarini MM, dos Santos MS, O'Brien PC, Ferguson-Smith MA (2013). "Chromosome painting in three species of buteoninae: a cytogenetic signature reinforces the monophyly of South American species". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e70071. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870071D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070071. PMC 3724671. PMID 23922908.

- ^ Smith HB (January 1927). "Chromosome Counts in the Varieties of SOLANUM TUBEROSUM and Allied Wild Species". Genetics. 12 (1): 84–92. doi:10.1093/genetics/12.1.84. PMC 1200928. PMID 17246516.

- ^ Li XL, Lin RS, Fung HL, Qi ZX, Song WQ, Chen RY (September 2001). "Chromosome numbers of some caespitose bamboos native in or introduced to China" 中国部分丛生竹类染色体数目报道 [Chromosome numbers of some caespitose bamboos native in or introduced to China]. Journal of Systematics and Evolution (in Chinese (China)). 39 (5): 433–442.

- ^ Guttenbach M, Nanda I, Feichtinger W, Masabanda JS, Griffin DK, Schmid M (2003). "Comparative chromosome painting of chicken autosomal paints 1-9 in nine different bird species". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 103 (1–2): 173–84. doi:10.1159/000076309. PMID 15004483. S2CID 23508684.

- ^ "Canis lupus familiaris (dog)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Maeda J, Yurkon CR, Fujisawa H, Kaneko M, Genet SC, Roybal EJ, et al. (2012). "Genomic instability and telomere fusion of canine osteosarcoma cells". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e43355. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...743355M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043355. PMC 3420908. PMID 22916246.

- ^ Lindblad-Toh K, Wade CM, Mikkelsen TS, Karlsson EK, Jaffe DB, Kamal M, et al. (December 2005). "Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog". Nature. 438 (7069): 803–19. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..803L. doi:10.1038/nature04338. PMID 16341006.

- ^ Aslam ML, Bastiaansen JW, Crooijmans RP, Vereijken A, Megens HJ, Groenen MA (November 2010). "A SNP based linkage map of the turkey genome reveals multiple intrachromosomal rearrangements between the turkey and chicken genomes". BMC Genomics. 11: 647. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-647. PMC 3091770. PMID 21092123.

- ^ a b Wang J, Roe B, Macmil S, Yu Q, Murray JE, Tang H, et al. (April 2010). "Microcollinearity between autopolyploid sugarcane and diploid sorghum genomes". BMC Genomics. 11: 261. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-261. PMC 2882929. PMID 20416060.

- ^ "Saccharum officinarum L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ Henry RJ, Kole C (15 August 2010). Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Sugarcane. CRC Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4398-4860-9.

- ^ Ohno S, Stenius C, Christian LC, Becak W, Becak ML (August 1964). "Chromosomal uniformity in the avian subclass Carinatae". Chromosoma. 15 (3): 280–8. doi:10.1007/BF00321513. PMID 14196875. S2CID 12310455.

- ^ Roslik, G.V. and Kryukov A. (2001). A Karyological Study of Some Corvine Birds (Corvidae, Aves). Russian Journal of Genetics 37(7):796-806. DOI: 10.1023/A:1016703127516

- ^ Gregory, T.R. (2015). Animal Genome Size Database. http://www.genomesize.com/result_species.php?id=1701

- ^ Akbarzadeh, M.; Van Laere, K.; Leus, L.; De Riek, J.; Van Huylenbroeck, J.; Werbrouck, S. P.; Dhooghe, E. (2021). "Can Knowledge of Genetic Distances, Genome Sizes and Chromosome Numbers Support Breeding Programs in Hardy Geraniums?". Genes. 12 (5): 730. doi:10.3390/genes12050730. PMC 8152959. PMID 34068148.

- ^ a b Schmid M, Fernández-Badillo A, Feichtinger W, Steinlein C, Roman JI (1988). "On the highest chromosome number in mammals". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 49 (4): 305–8. doi:10.1159/000132683. PMID 3073914.

- ^ Hosseini SJ, Elahi E, Raie RM (2004). "The Chromosome Number of the Persian Gulf Shrimp Penaeus semisulcatus". Iranian Int. J. Sci. 5 (1): 13–23.

- ^ Spoz A, Boron A, Porycka K, Karolewska M, Ito D, Abe S, et al. (2014). "Molecular cytogenetic analysis of the crucian carp, Carassius carassius (Linnaeus, 1758) (Teleostei, Cyprinidae), using chromosome staining and fluorescence in situ hybridisation with rDNA probes". Comparative Cytogenetics. 8 (3): 233–48. doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v8i3.7718. PMC 4205492. PMID 25349674.

- ^ Gallardo MH, Bickham JW, Honeycutt RL, Ojeda RA, Köhler N (September 1999). "Discovery of tetraploidy in a mammal". Nature. 401 (6751): 341. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..341G. doi:10.1038/43815. PMID 10517628. S2CID 1808633.

- ^ Gallardo MH, González CA, Cebrián I (August 2006). "Molecular cytogenetics and allotetraploidy in the red vizcacha rat, Tympanoctomys barrerae (Rodentia, Octodontidae)". Genomics. 88 (2): 214–21. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.02.010. PMID 16580173.

- ^ Contreras LC, Torres-Mura JC, Spotorno AE (May 1990). "The largest known chromosome number for a mammal, in a South American desert rodent". Experientia. 46 (5): 506–8. doi:10.1007/BF01954248. PMID 2347403. S2CID 33553988.

- ^ Maneechot N, Yano CF, Bertollo LA, Getlekha N, Molina WF, Ditcharoen S, et al. (2016). "Genomic organization of repetitive DNAs highlights chromosomal evolution in the genus Clarias (Clariidae, Siluriformes)". Molecular Cytogenetics. 9: 4. doi:10.1186/s13039-016-0215-2. PMC 4719708. PMID 26793275.

- ^ Symonová R, Havelka M, Amemiya CT, Howell WM, Kořínková T, Flajšhans M, et al. (March 2017). "Molecular cytogenetic differentiation of paralogs of Hox paralogs in duplicated and re-diploidized genome of the North American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula)". BMC Genetics. 18 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/s12863-017-0484-8. PMC 5335500. PMID 28253860.

- ^ "Chromosome numbers of Polish ferns". researchgate.net.

- ^ Islam-Faridi N, Sakhanokho HF, Dana Nelson C (August 2020). "New chromosome number and cyto-molecular characterization of the African Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) - "The Tree of Life"". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 13174. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1013174I. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-68697-6. PMC 7413363. PMID 32764541.

- ^ Eschmeyer WM. "Family Petromyzontidae – Northern lampreys".

- ^ Flora of North America Editorial Committee (1993). Flora of North America. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis.

- ^ Lukhtanov VA, Kandul NP, Plotkin JB, Dantchenko AV, Haig D, Pierce NE (July 2005). "Reinforcement of pre-zygotic isolation and karyotype evolution in Agrodiaetus butterflies". Nature. 436 (7049): 385–9. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..385L. doi:10.1038/nature03704. PMID 16034417. S2CID 4431492.

- ^ "Morus nigra (black mulberry)". www.cabi.org. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Zeng Q, Chen H, Zhang C, Han M, Li T, Qi X, et al. (2015). "Definition of Eight Mulberry Species in the Genus Morus by Internal Transcribed Spacer-Based Phylogeny". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0135411. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035411Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135411. PMC 4534381. PMID 26266951.

- ^ a b Lukhtanov VA (2015). "The blue butterfly Polyommatus (Plebicula) atlanticus (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) holds the record of the highest number of chromosomes in the non-polyploid eukaryotic organisms". Comparative Cytogenetics. 9 (4): 683–90. doi:10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i4.5760. PMC 4698580. PMID 26753083.

- ^ Lukhtanov VA (2015-07-10). "The blue butterfly Polyommatus (Plebicula) atlanticus (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) holds the record of the highest number of chromosomes in the non-polyploid eukaryotic organisms". Comparative Cytogenetics. 9 (4): 683–90. doi:10.3897/compcytogen.v9i4.5760. PMC 4698580. PMID 26753083.

- ^ Sinha BM, Srivastava DP, Jha J (1979). "Occurrence of Various Cytotypes of Ophioglossum ReticulatumL. In a Population from N. E. India". Caryologia. 32 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1080/00087114.1979.10796781.

- ^ Mochizuki K (2010). "DNA rearrangements directed by non-coding RNAs in ciliates". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. RNA. 1 (3): 376–87. doi:10.1002/wrna.34. PMC 3746294. PMID 21956937.

- ^ Miller, Greg (17 September 2014). "This Bizarre Organism Builds Itself a New Genome Every Time It Has Sex". Wired. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Kumar S, Kumari R (June 2015). "Origin, structure and function of millions of chromosomes present in the macronucleus of unicellular eukaryotic ciliate, Oxytricha trifallax: a model organism for transgenerationally programmed genome rearrangements". Journal of Genetics. 94 (2): 171–6. doi:10.1007/s12041-015-0504-2. PMID 26174664. S2CID 14181659.

- ^ Swart EC, Bracht JR, Magrini V, Minx P, Chen X, Zhou Y, et al. (2013-01-29). "The Oxytricha trifallax macronuclear genome: a complex eukaryotic genome with 16,000 tiny chromosomes". PLOS Biology. 11 (1): e1001473. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001473. PMC 3558436. PMID 23382650.

- ^ Yong E (6 February 2013). "You Have 46 Chromosomes. This Pond Creature Has 15,600". National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013.

- ^ Avarello R, Pedicini A, Caiulo A, Zuffardi O, Fraccaro M (May 1992). "Evidence for an ancestral alphoid domain on the long arm of human chromosome 2". Human Genetics. 89 (2): 247–9. doi:10.1007/BF00217134. PMID 1587535. S2CID 1441285.

Further reading

- Makino, Sajiro (1951). An atlas of the chromosome numbers in animals. MBLWHOI Library. Ames, Iowa State College Press.

- Bell G (1982). The Masterpiece of Nature: The Evolution and Genetics of Sexuality. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 450. ISBN 9780856647536. (table with a compilation of haploid chromosome number of many algae and protozoa, in column "HAP").

- Nuismer SL, Otto SP (July 2004). "Host-parasite interactions and the evolution of ploidy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (30): 11036–9. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111036N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403151101. PMC 503737. PMID 15252199. Supporting Data Set, with information on ploidy level and number of chromosomes of several protists)

External links

- List of pages in English from Russian bionet site

- The dog through evolution (archived 1 March 2012)

- Shared synteny of human chromosome 17 loci in Canids (archived 24 September 2015)

- An atlas of the chromosome numbers in animals (1951); PDF downloads of each chapter on Internet Archive

![Fusion of ancestral chromosomes left distinctive remnants of telomeres, and a vestigial centromere. As other non-human extant hominidae have 48 chromosomes it is believed that the human chromosome 2 is the result of the merging of two chromosomes.[139]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/71/Chromosome2_merge.png)