Effects of the storage conditions on the stability of natural and synthetic cannabis in biological matrices for forensic toxicology analysis: An update from the literature

Contents

Latin American art is the combined artistic expression of Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, as well as Latin Americans living in other regions.

The art has roots in the many different indigenous cultures that inhabited the Americas before European colonization in the 16th century. The indigenous cultures each developed sophisticated artistic disciplines, which were highly influenced by religious and spiritual concerns. Their work is collectively known and referred to as Pre-Columbian art. The blending of Amerindian, European and African cultures has resulted in a unique Mestizo tradition.

Colonial period

During the colonial period, a mixture of indigenous traditions and European influences (mainly due to the Christian teachings of Franciscan, Augustinian and Dominican friars) produced a very particular Christian art known as Indochristian art. In addition to indigenous art, the development of Latin American visual art was significantly influenced by Spanish, Portuguese, and French and Dutch Baroque painting. In turn Baroque painting was often influenced by the Italian masters.

The Cuzco School is viewed as the first center of European-style painting in the Americas. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Spanish art instructors taught Quechua artists to paint religious imagery based on classical and Renaissance styles.[1]

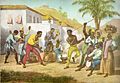

In eighteenth-century New Spain, Mexican artists along with a few Spanish artists produced paintings of a system of racial hierarchy, known as casta paintings. It was almost exclusively a Mexican form however, one set was produced in Peru. In a break from religious paintings of the preceding centuries, casta paintings were a secular art form. Only one known casta painting by a relatively unknown painter, Luis de Mena, combines castas with Mexico's Virgin of Guadalupe; this being an exception. Some of Mexico's most distinguished artists painted casta works, including Miguel Cabrera. Most casta paintings were on multiple canvases, with one family grouping on each. There were a handful of single canvas paintings, showing the entire racial hierarchy. The paintings show idealized family groupings, with the father being of one racial, the mother of another racial category, and their offspring being a third racial category. This genre of painting flourished for about a century, coming to an end with Mexican independence in 1821, and the abolition of legal racial categories.[2]

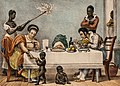

In the seventeenth century, The Netherlands had captured the rich sugar-producing area of the Portuguese colony of Brazil (1630–1654). During that period, Dutch artist Albert Eckhout painted a number of important depictions of social types in Brazil. These depictions included images of indigenous men and women, as well as still lifes.[3]

Scientific expeditions approved by the Spanish crown began exploring Spanish America where its flora and fauna were recorded. Spaniard José Celestino Mutis, a medical doctor and horticulturalist and follower of Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus, led an expedition starting in 1784 to northern South America, the expedition is known as the Expedición Botánica de Nueva Granada. Local artists were Ecuadorean Indians, who produced five thousand color drawings of nature, all being published. The crown chartered expedition whose purpose was scientific recording of the natural beauty and wealth of Nature, was a departure from the long traditional religious art.[4]

The most important scientific expedition was that of Alexander von Humboldt and French botanist Aimé Bonpland. They traveled for five years throughout Spanish America (1799-1804), exploring and recording scientific information as well as the attire and lifestyles local populations.[5] Humboldt's work became an inspiration and template for continuing scientific work in the nineteenth century, as well as traveller reporters who recorded the scenes of everyday life.

In 1818, the Academy of San Alejandro in Havana, Cuba, was founded by Alejandro Ramírez, and the French painter Jean Baptiste Vermay, served as the founding director.[6][7] It is the oldest academy of art in Latin America.[8]

Historiography of colonial art and architecture

The history of Latin American art has generally been written by those with training in art history departments. However, the concept of "visual culture" has now brought scholars trained in other disciplines to write the histories of art. It became more prevalent through the later 1900's.[9] As with the history of indigenous peoples, for many years there was a focus on either the pre-Columbian period (Olmec, Maya, Aztec, Inca) art production, then a leap to the twentieth century. More recently, the colonial era and the nineteenth century have developed as fields of focus. Visual culture as a field increasingly crosses disciplinary boundaries. Colonial architecture has been the subject of a number of important studies.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

Colonial art has a long tradition, especially in Mexico, with there being publications of Manuel Toussaint.[16] In recent years, there has been a boom in publications on colonial art, with some useful overviews being published in recent years.[17][18][19][20][21][22] Many works deal exclusively with Spanish America.

Major exhibitions on colonial art have resulted in fine catalogs as a permanent record.[23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Gallery

-

Official portrait of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo

-

Virgin of Carmel Saving Souls in Purgatory,. Peru. Circle of Diego Quispe Tito, 17th century, collection of the Brooklyn Museum

-

The Marriage of Captain Martin de Loyola to Beatriz Ñusta, detail, c. 1675–1690, Church of la Compañía de Jesús, Cuzco, Peru.

-

Our Lady of Bethelem, Peru, anonymous, 18th century

-

Viceroy of Peru, Don José Manso de Velasco, 1st Count of Superunda 18th c.

-

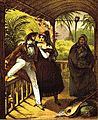

Vicente Alban. Spanish woman and her black slave. Quito, 18th century

-

Mestizo, Mestiza, Mestizo Peruvian casta painting, showing intermarriage within a casta category. 18th c.

-

Miguel Cabrera (Mexico) Casta painting, From Spaniard and Mulatta, Morisca. Oil on canvas. Private collection. 18th c.

-

Albert Eckhout, Tupi (Brazil) dancing, 17th c.

-

Albert Eckhout African Woman in Brazil, 17th c.

-

Aleijadinho(Brazil): Angel of the Passion, ca. 1799. Congonhas do Campo

-

Alexander von Humboldt (German) Drawing of volcano and climatic zones

Nineteenth-century

Gallery – Foreign artists in Latin America

-

Johann Moritz Rugendas (German) Costumes in Rio, Brazil 1823

-

Johann Moritz Rugendas (German) Slave hunter, Brazil 1823

-

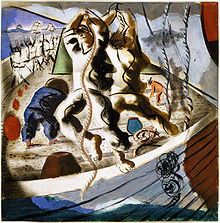

Johann Moritz Rugendas (German) Capoeira or the Dance of War Brazil 1835.

-

Johann Moritz Rugendas Brazilian dance lundu Brazil 1835

-

Jean Baptiste Debret (French) "L’execution de la Punition du Fouet" ("Execution of the Punishment of the Whip") (Brazil)

-

Jean Baptiste Debret (French) "Feitors corrigeant des negres" ("Plantation overseers disciplining blacks") Brazil

-

Jean Baptiste Debret (French) Family dining, Brazil

-

Claudio Linati (Italian) Apache chief. Mexico 1828.

-

Carl Nebel (German) Las Tortilleras, Voyage pittoresque et archéologique dans la partie la plus intéressante du Mexique. Mexico. Early 19th c.

-

Frederick Catherwood (British). Main temple at Tulum (Mexico), from Views of Ancient Monuments.

-

Daniel Thomas Egerton (British), The aqueduct of Zacatecas, Mexico, 1838, now in the Franz Mayer Museum

-

Frederic Edwin Church (U.S.) Tropical Scenery (1873)

Gallery – Latin American artists

-

Carmelo Fernández (Venezuela). Muleteer and Hat Weaver in Vélez. 1850. watercolor. National Library of Colombia

-

Cristóbal Rojas. (Venezuela) La taberna. 1887.

-

Arturo Michelena (Venezuela) La Joven Madre 1889

-

Ángel Della Valle (Argentina) The Return of the Malón (1892)

-

Carlos Morel (Argentina), Payada en una pulpería.

-

Prilidiano Pueyrredón (Argentina) A Stop in the Countryside

-

Juan Manuel Blanes (Uruguay) Paraguay: Image of Your Desolate Country (1879)

-

Manuel Antonio Caro (Chile) The Abdication of Bernardo O'Higgins

-

Alejandro Ciccarelli (Chile) Vista de Santiago de Chile desde Peñalolén".

-

Antonio Smith (Chile) Cordillera and Lake. Late 19th c.

-

Juan Francisco González (Chile), Calle de Limache. González is considered one of Chile's greatest painters.

-

José Gil de Castro (Peru) José Olaya (1828)

-

Pancho Fierro, Afro-Peruvian artist, Veiled women (tapadas) going to church

-

Francisco Laso (Peru) The Three Races or, Equality before the Law

-

Victor Meirelles: First Mass in Brazil, 1861, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, an example of Brazilian academic art

-

Agostinho José da Mota (Brazil) Factory at Barão de Capanema, 1862, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes

-

José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior (Brazil) Reading Woman, 1892

-

Pedro Weingartner (Brazil). After the Flood Meseu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro

-

Victor Patricio de Landaluze (Cuba) Cutting Sugar Cane, 1874

-

Agustín Arrieta, El Costeño. Private collection. The painting shows a boy from the coast, likely Veracruz, holding a basket of fruits including mamey, tuna and pitahaya

-

José María Velasco (Mexico) View of the Valley of Mexico

Modernism

Modernism, a Western art movement typified by the rejection of traditional classical styles. This movement holds an ambivalent position in Latin American art. Not all countries developed modernized urban centers at the same time, so Modernism's appearance in Latin America is difficult to date. While Modernism was welcomed by some, others rejected it. Generally speaking, the countries of the Southern Cone were more open to foreign influence, while countries with a stronger indigenous presence such as Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia were resistant to European culture.[30]

A landmark event for Modernism in the region was, the Semana de Arte Moderna or Modern Art Week, a festival that took place in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1922, marking the beginning of Brazil's Modernismo movement. "[T]hough a number of individual Brazilian artists were doing modernist work before the Week, it coalesced and defined the movement and introduced it to Brazilian society at large."[citation needed]

Constructivist movement

In general, the artistic Eurocentrism associated with the colonial period began to fade in the early twentieth century, as Latin Americans began to acknowledge their unique identity and started to follow their own path.

From the early twentieth century onward, the art of Latin America was greatly inspired by Constructivism.[citation needed] It quickly spread from Russia to Europe, and then into Latin America. Joaquín Torres García and Manuel Rendón have been credited with bringing the constructivism to Latin America.[citation needed]

After a long and successful career in Europe and the United States, Torres García returned to his native Uruguay in 1934, where he both promoted Constructivism and augmented it into a uniquely Uruguayan movement: Universal Constructivism. Attracting a circle of experienced peers and young artists as followers in Montevideo, in 1935 he founded the Asociación de Arte Constructivo as an art center and exhibition space for his circle. The venue was closed in 1940 due to a lack of funding. In 1943, he opened the Taller Torres-García, a workshop and training center that operated until 1962.[31]

Muralism

Muralism or Muralismo is an important artistic movement generated in Latin America. It is popularly represented by the Mexican muralism movement of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rufino Tamayo. In Chile, José Venturelli and Pedro Nel Gómez were influential muralists. Santiago Martinez Delgado championed muralism in Colombia, as did Gabriel Bracho in Venezuela. In the Dominican Republic, Spanish exile José Vela Zanetti was a prolific muralist, painting over 100 murals in the country. The Ecuadorian artist Oswaldo Guayasamín (a student of Orozco), the Brazilian Candido Portinari, and Bolivian Miguel Alandia Pantoja are also noteworthy. Some of the most impressive Muralista works can be found in Mexico, Colombia, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago and Philadelphia. Mexican Muralism "enjoyed a type of prestige and influence in other countries that no other American art movement had ever experienced."[32] Through Muralism, artists in Latin America found a distinctive art form that provided for political and cultural expression, often focusing on issues of social justice related to their indigenous roots.[30]

Generación de la Ruptura

Generación de la Ruptura, or "Rupture Generation," (sometimes simply known as "Ruptura") is the name given to an art movement in Mexico in the 1960s in which younger artists broke away from the established national style of Muralismo. Born out of the desire of younger artists for greater freedom of style in art, this movement is marked by expressionistic and figurative styles. Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas is credited with initiating the Ruptura. In 1958, Cuevas published a paper called La Cortina del Nopal ("The Cactus Curtain"), which condemned Mexican muralism as overly political, calling it "cheap journalism and harangue" rather than art.[30] Representative artists include José Luis Cuevas, Alberto Gironella, and Rafael Coronel.

Nueva Presencia

Nueva Presencia ("new presence") was an artist group founded by artists Arnold Belkin and Francisco Icaza in the early 1960s. In response to WWII atrocities such as the Holocaust and the atomic bomb, the artists of Nueva Presencia shared an anti-aesthetic rejection of contemporary trends in art and believed that the artist had a social responsibility. Their beliefs were outlined in the Nueva Presencia manifesto, which was published in the first issue of the poster review of the same name. "No one, especially the artist, has the right to be indifferent to the social order."[31] Members of the group included Francisco Corzas (b. 1936), Emilio Ortiz (b. 1936), Leonel Góngora (b.1933), Artemio Sepúlveda (b. 1936), and José Muñoz, and photographer Ignacio "Nacho" López.

Surrealism

The French poet and founder of Surrealism, André Breton, after visiting Mexico in 1938, proclaimed it to be "the surrealist country par excellence."[31] Surrealism, an artistic movement originating in post-World War I Europe, strongly impacted the art of Latin America. This is where the Mestizo culture, the legacy of European conquer over indigenous peoples, embodies contradiction, a central value of Surrealism.[33]

The widely known Mexican painter Frida Kahlo painted self-portraits and depictions of traditional Mexican culture in a style that combines Realism, Symbolism and Surrealism. Although, Kahlo did not commend this label, once saying, "They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality."[34] Kahlo's work commands the highest selling price of all Latin American paintings, and the second-highest for any female artist.[35] Other female Mexican Surrealists include Leonora Carrington (a British woman who relocated to Mexico) and Remedios Varo (a Spanish exile). Mexican artist Alberto Gironella, Chilean artists Roberto Matta, Mario Carreño Morales, and Nemesio Antúnez, Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, and Argentine artist Roberto Aizenberg have also been classified as Surrealists.

-

Remedios Varo (Mexico) Roulotte, 1956

Contemporary Art

Since roughly the 1970s, artists from all parts of Latin America have made important contributions to international contemporary art, from conceptual sculptors like Doris Salcedo (from Colombia) and Daniel Lind-Ramos (from Puerto Rico), to painters like Myrna Báez (from Puerto Rico), to artists working in media like photography, such as Vik Muniz (from Brazil).

Styles and trends

Figuration

European classical art styles have made a long-lasting impression on the art of Latin America. Into the twentieth century, many Latin American artists continued to be schooled in the traditional 19th-century style, resulting in a continued emphasis on figurative work. Due to the far reach of figuration, the work often spans upon a number of different styles such as Realism, Pop art, Expressionism, and Surrealism, only naming a few. While these artists confront issues that range from the personal to the political, many have a shared interest in indigenous issues and the heritage of European cultural imperialism.

One movement devoted to figuration was Otra Figuración (Other Figuration), an Argentine artist group and commune formed in 1961 and disbanded in 1966. Members Rómulo Macció, Ernesto Deira, Jorge de la Vega, and Luis Felipe Noé lived together and shared a studio in Buenos Aires. Artists of Otra Figuración worked in an expressionistic abstract figurative style featuring vivid colors and collage. Although Otra Figuración were contemporaries of Nueva Presencia, there was no direct contact between the two groups.[31] People who are sometimes associated with the group are Raquel Forner, Antonio Berni, Alberto Heredia, and Antonio Seguí.

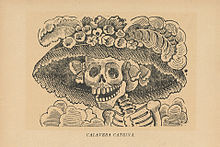

Parody and sociopolitical critique

Art in Latin America has often been used as a means of social and political critique. Mexican graphic artist José Guadalupe Posada drew harsh images of Mexican elites as skeletons, calaveras. This was done prior to the Mexican Revolution, strongly influencing later artists, such as Diego Rivera. A common practice among Latin American figurative artists is to parody Old Master paintings, especially those of the Spanish court produced by Diego Velázquez in the 17th century. These parodies serve a dual purpose, referring to the artistic and cultural history of Latin America, and critiquing the legacy of European cultural imperialism in Latin American nations. Artists Fernando Botero, Herman Braun-Vega and Alberto Gironella frequently employed this technique.

Colombian figurative artist Fernando Botero, whose work features unique "puffy" figures in various situations addressing themes of power, war, and social issues, has used this technique to draw parallels between current governing bodies and the Spanish monarchy. His 1967 painting The Presidential Family, is an early example. The painting, echoing Diego Velázquez's 1656 Spanish court painting Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), contains a self-portrait of Botero standing behind a large canvas. The thick, "puffy" presidential family, decked out in fashionable finery and staring blandly out of the canvas, appear socially superior, drawing attention to social inequality.[33] According to Botero, his "puffy" figures are not meant to be satirical. He painted a powerful series of canvases, which are based on photos of torture by the U.S. military of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison.

- The deformation you see is the result of my involvement with painting. The monumental and, in my eyes, sensually provocative volumes stem from this. Whether they appear fat or not does not interest me. It has hardly any meaning for my painting. My concern is with formal fullness, abundance. And that is something entirely different.[30]

Among Peruvian painter Herman Braun-Vega, the appropriation of works of the old masters is almost systematic from the 1970s.[36] The characters he borrows from the iconography of European painting are often confronted with the social and political situation of Latin America.[37] In his painting La leçon... à la campagne (Rembrandt) in 1984, he takes the scene from Rembrandt’s painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, transporting it outside to the countryside and substituting for certain characters from the original painting, contemporary Latin American characters who refer to the social and political situation of South America as confirmed by the texts of the press clippings transfers of the newspaper Le Monde which structures the feet of the corpse in the cubist way.[38] In 1987, in his painting Double focus over the West (Velazquez and Picasso), he turned Velazquez's painting Las Meninas into a critic of the power of the Church by replacing the royal couple in the mirror of the back of the room by Pope John Paul II receiving Kurt Waldheim in the Vatican.[39] Among many other examples, we can still cite the painting Los caprichos del F.M.I. (Goya) of 2003 where El Tiempo y las viejas and some engravings from Los caprichos de Goya are featured to criticize the sermonizers of the International Monetary Fund.[40]

Mexican painter and collagist Alberto Gironella, whose style mixes elements of Surrealism and Pop art, also produced parodies of official Spanish court paintings. He completed dozens of versions of Velásquez's Queen Mariana from 1652. Gironella's parodies critique the Spanish rule of Mexico by incorporating subversive imagery. ‘’La Reina de los Yugos’’ or "The Queen of Yokes" (1975–81) depicts Mariana with a skirt made of upside-down ox yokes, signifying both Spanish dominance over Mexico's indigenous peoples, and those people's subversion of Spanish rule. The yokes are rendered useless by being upturned. "[Gironella's] hallmark was the use of particular Spanish Grocery cans (sardines, mussels, etc.) in his works, and soda bottle caps nailed or glued around the rim of his paintings."

Cuban artist Sandra Ramos' paintings, etchings, installations, collages, and digital animation often tackle taboo subjects in contemporary Cuban society such as racism, mass migration, communism and social injustices in contemporary Cuban society.[41][42]

Photography

Picture taken of Che Guevara by Alberto Korda on March 5, 1960, at the La Coubre memorial service.

Photographers captured on film, indigenous peoples as well as distinct social types, such as the gauchos of Argentina. A number of Latin Americans have made significant contributions to modern photography. Guy Veloso and José Bassit photograph the Brazilian religiosity. Guillermo Kahlo photographed Mexican colonial buildings and infrastructure, such as the railway bridge at Metlac. Agustín Casasola himself took many images of the Mexican Revolution, and compiled an extensive archive of Mexican photos. Other photographers include indigenous Peruvian Martín Chambi, Mexican Graciela Iturbide, and Cuban Alberto Korda, famous for his iconic image of Che Guevara. Mario Testino is a noted Peruvian fashion photographer. In addition, a number of non-Latin American photographers have focused on the area, including Tina Modotti and Edward Weston in Mexico. Guatemalan national María Cristina Orive has worked in Argentina with Sara Facio. Ecuadoran Hugo Cifuentes has garnered attention.

Gallery

-

Photo of an Argentine gaucho. Courret Hermanos Fotogs., Lima, Peru (1868)

-

Martín Chambi (Peru) photo of a man at Machu Picchu, published in Inca Land. Explorations in the Highlands of Peru, 1922

-

Guy Veloso. Brazilian Penitents, 2002. Gelatin silver print

See also

- Argentine art

- Bolivian art

- Brazilian art

- Chilean art

- Colombian art

- Costa Rican art

- Cuban art

- Dominican art

- Ecuadorian art

- Guatemalan art

- Honduran art

- Mexican art

- Nicaraguan art

- Panamanian art

- Paraguayan art

- Peruvian art

- Puerto Rican art

- Salvadoran art

- Uruguayan art

- Venezuelan art

- List of Latin American artists

- Latin American culture

- Mexican Muralism

- Chilote School of Religious Imagery

- Indochristian art

- Paraguayan Indian art

- Pre-Columbian art

- Visual arts by indigenous peoples of South America

References

- ^ The "Cusquenha" Art. Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine Museu Histórico Nacional. (retrieved 30 April 2009)

- ^ Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting, New Haven: Yale University Press 2005.

- ^ Dawn Ades, "Nature, Science, and the Picturesque" in Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, 1820–1980, London: South Bank Center 1989, 64–65.

- ^ Stanton L. Catlin, "Traveller-Reporter Artists and the Empirical tradition in Post Independence Latin American Art" in Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, 1820-1980, London: South Bank Center 1989, pp. 43-45, color plate 3.2 p. 44.

- ^ Alexander von Humboldt, Voyage de Humboldt et de Bonpland, Première Partie; Relation Historique: Atlas Pittoresque: 'Vues de Cordillères et monuments de peuples indigènes de l'Amérique', Paris 1810.

- ^ "Fundada la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro". La Jiribilla (in European Spanish). September 7, 2018. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- ^ WPnew (2018-11-27). "Art Schools: San Alejandro Academy". InterfineArt. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ^ "Cuban Art: History & Artists". Study.com. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ^ "Latin American art | History, Artists, Works, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ George Kubler, Mexican Architecture of the Sixteenth Century. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press 1948.

- ^ John McAndrew, The Open-Air Churches of Sixteenth-Century Mexico: Atrios, Posas, Open Chapels, and Other Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1965.

- ^ James Early, The Colonial Architecture of Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1994.

- ^ James Early, Presidio, Mission, and Pueblo: Spanish Architecture and Urbanism in the United States. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press 2004.

- ^ Valerie Fraser. The Architecture of Conquest: Building in the Viceroyalty of Peru, 1535–1635. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1989.

- ^ Harold Wethey, Colonial Architecture and Sculpture in Peru. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1949.

- ^ Manuel Toussaint, Arte colonial en México. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 1948. 5th edition 1990.

- ^ Damian Bayon and Murrillo Marx, History of South American Colonial Art and Architecture. New York: Rizzoli 1989.

- ^ Marcus Burke, Treasures of Mexican Colonial Painting. Davenport IA: The Davenport Museum of Art 1998.

- ^ Richard Kagan, Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793. New Haven: Yale University Press 2000.

- ^ Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Art of Colonial Latin America. London: Phaidon 2005

- ^ Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521–1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2008.

- ^ Emily Umbeger and Tom Cummins, eds.Native Artists and Patrons in Colonial Spanish America. Phoebus: A Journal of Art History. Phoenix: Arizona State University 1995.

- ^ Linda Bantel and Marcus Burke, Spain and New Spain: Mexican Colonial Arts in their European Context. Exhibition catalog. Corpus Christi TX: Art Museum of South Texas 1979.

- ^ María Concepción García Sáiz, Las castas mexicanas: Un género pictórico americano. Milan: Olivetti 1989.

- ^ New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America. Exhibition catalog. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996.

- ^ Diana Fane, ed. Converging Cultures: Art and Identity in Spanish America. Exhibition catalog. New York: The Brooklyn Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams. 1996.

- ^ Los Siglos de oro en los Virreinatos de América 1550–1700. Exhibition catalog. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V, 1999.

- ^ Donna Pierce et al., Painting a New World: Mexican Art and Life 1521–1821. Exhibition catalog. Denver: Denver Art Museum 2004.

- ^ The Arts in Latin America: 1492–1820. Exhibition catalog. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art 2006.

- ^ a b c d Lucie-Smith, Edward. Latin American Art of the 20th Century. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1993.

- ^ a b c d Barnitz, Jacqueline. Twentieth Century Art of Latin America. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2001.

- ^ Sullivan, Edward. Latin American Art. London: Phaidon Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-7148-3980-6

- ^ a b Baddeley, Oriana & Fraser, Valerie. Drawing the Line: Art and Cultural Identity in Contemporary Latin America. London: Verso, 1989.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo - Surrealist Conflict | PDF | Surrealism | Paintings".

- ^ Moses, Tai. Saint Frida. MetroActive: Books. 9 Nov 2005 (retrieved 18 April 2009)

- ^ Ramón Ribeyro, Julio (1981-05-17). "Herman Braun". Marka (in Spanish). Peru: Caballo Rojo: 14.

The fact that a painter uses the works of other painters as subjects for his paintings is not new. What is new is to deepen this procedure and make it, forcing a little the term, a system.

- ^ "Herman Braun: trato de ofrecer un testimonio de la situación social". El Comercio (in Spanish). Lima. 1984-11-30.

During those fifteen years, I worked with western iconography, trying to offer a testimony, a critique, of the social situation.

- ^ Valette-Fondo, Madeleine. "L'interpicturalité dans quelques tableaux de Braun-Vega" [Interpicturality in some Braun-Vega paintings] (in French). sens public.

Inspiré du collage cubiste, le fragment du journal Le Monde oriente la lecture d'une situation historiquement datée (les années soixante), mais toujours actuelle, le combat des mouvements de libération populaire contre l'arbitraire d'un régime d'occupation-répression.

- ^ Cárdenas Moreno, Mónica (2016). "La culture populaire péruvienne à l'intérieur de la tradition artistique européenne. Passage et métissage dans la peinture d'Herman Braun-Vega" (in French). Amerika – via OpenEdition Journals.

Le pouvoir est critiqué de plusieurs façons : grâce au déplacement des personnages comme nous avons pu le constater dans le cas de l'infante Marguerite; et aussi par le remplacement des personnages le plus puissants de la scène : le couple royal reflété dans le miroir. Braun-Vega rend contemporain le pouvoir représenté dans le miroir à travers deux personnages : le pape Jean Paul II accompagné par son invité au Vatican Kurt Waldheim (visite qui avait fait scandale en 1987), l'ancien secrétaire général de l'ONU de 1972 à 1981 dont le passé nazi ne fut pas un obstacle pour devenir président de l'Autriche en 1986.

- ^ Bessière, Bernard; Megevand, Sylvie; Bessière, Christiane (2008). "Los Caprichos del FMI (Goya, Picasso)". La peinture hispano-américaine (in French) (Éditions du temps ed.). Nantes: éditions du temps. pp. 270–274. ISBN 978-2-84274-427-4.

Mais que peuvent bien tramer ces deux femmes et tous les personnages du fond ? Manifestement liés au Fonds Monétaire International, institution chargée depuis 1944 de réguler le système monétaire de la planète, sans doute délibèrent-ils doctement sur son devenir, en particulier celui des régions pudiquement nommées «en développement».

- ^ "Bridging Past, Present, and Future: A Conversation with Cuban Artist Sandra Ramos | Kellogg Institute For International Studies". Kellog Institute at The University of Notre Dame. 2017-11-06. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ^ Staff, AiA (2010-10-07). "US Welcomes Cuban Artists". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

Further reading

- Ades, Dawn. Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, 1820-1980. New Haven: Yale University Press 1989.

- Alcalá, Luisa Elena and Jonathan Brown. Painting in Latin America: 1550-1820. New Haven: Yale University Press 2014.

- Angulo-Iñiguez, Diego, et al. Historia del Arte Hispano-Americano. 3 vols. (Barcelona 1945-56).

- Anreus, Alejandro, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg, eds. The Social and the Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere. University Park: Penn State University Press 2006.

- Baddeley, Oriana; Fraser, Valerie (1989). Drawing the Line: Art and Cultural Identity in Contemporary Latin America. London: Verso. ISBN 0-86091-239-6.

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. Art of Colonial Latin America. New York: Phaidon Press 2005.[1]

- Barnitz, Jacqueline. Twentieth-Century Art of Latin America. Austin: University of Texas Press 2001.

- Bayón, D. and M. Marx. History of South American Colonial Art and Architecture. New York 1992.

- Bottineau, Yves. Iberian-American Baroque. New York 1970.

- Cali, François. The Spanish Arts of Latin America. New York 1961.

- Castedo, Leopoldo. A History of Latin American Art and Architecture. New York and Washington, D.C. 1969.

- Craven, David. Art and Revolution in Latin America, 1910-1990. New Haven: Yale University Press 2002.

- Dean, Carolyn and Dana Leibsohn, "Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America," Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 12, No. 1, 2003.

- del Conde, Teresa (1996). Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. London: Phaidon Press Limited. ISBN 0-7148-3980-9.

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2008.

- Fane, Diana, ed. Converging Cultures: Art and Identity in Spanish America. (exhibition catalogue Brooklyn Museum of Art 1996.

- Fernández, Justino (1965). Mexican Art. Mexico D.F.: Spring Books.

- Frank, Patrick, ed. Readings in Latin American Modern Art. New Haven: Yale University Press 2004.

- Goldman, Shifra M. Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin America and the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1994.

- Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The Word Made Image: Religion, Art, and Architecture in Spain and Spanish America, 1500-1600. Boston 1998.

- Kagan, Richard. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493-1793. New Haven: Yale University Press 2000.

- Keleman, Pal. Baroque and Rococo in Latin America. New York 1951.

- Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century. New York: MoMA 1992.

- Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States. New York: Bronx Museum 1989.

- Padilla, Carmela, ed. Conexiones/Connections in Spanish Colonial Art. Santa Fe 2002.

- Palmer, Gabrielle and Donna Pierce. Cambios: The Spirit of Transformation in Spanish Colonial Art. Exhibition Catalog, Santa Barbara Museum of Art 1992.

- Ramírez, Mari Carmen and Héctor Olea, eds. Inverted Utopias: Avant Garde Art in Latin America. New Haven: Yale University Press 2004.

- Reyes-Valerio, Constantino (2000). Arte Indocristiano, Escultura y pintura del siglo XVI en México (in Spanish). Mexico D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. ISBN 970-18-2499-7.

- Reyes-Valerio, Constantino (1993). De Bonampak al Templo Mayor: El azul maya en Mesoamérica (in Spanish). Mexico D.F.: Siglo XXI editores. ISBN 968-23-1893-9. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- Scott, John F. Latin American Art: Ancient to Modern. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1999.

- Los Siglos de Oro en los Virreinatos de América, 1550-1700. Exh. cat. Madrid: Museo de América, 1999.

- Sullivan, Edward. Latin American Art. London: Phaidon Press, 2000.

- Stofflet, Mary (1991). Latin American Drawings Today. San Diego Museum of Art. ISBN 0-295-97107-X.

- Turner, Jane, ed. Encyclopedia of Latin American and Caribbean Art. New York: Grove's Dictionaries 2000.

- Webster, Susan Verdi. Lettered Artists and the Languages of Empire: Painters and the Profession in Early Colonial Quito. Austin: University of Texas Press 2017. ISBN 978-1-4773-1328-2

External links

- Walker, John. "Latin American Art". Glossary of Art, Architecture & Design since 1945, 3rd. ed.

- Museum of Latin American Art

- Latineos - Latin America, Caribbean, arts and culture

- Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820