Effects of the storage conditions on the stability of natural and synthetic cannabis in biological matrices for forensic toxicology analysis: An update from the literature

Contents

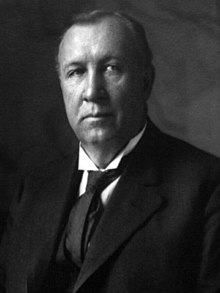

Hoke Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Georgia | |

| In office November 16, 1911 – March 3, 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph M. Terrell |

| Succeeded by | Thomas E. Watson |

| 58th Governor of Georgia | |

| In office July 1, 1911 – November 16, 1911 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Mackey Brown |

| Succeeded by | John M. Slaton |

| In office June 29, 1907 – June 26, 1909 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph M. Terrell |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Mackey Brown |

| 19th United States Secretary of the Interior | |

| In office March 6, 1893 – September 1, 1896 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | John Willock Noble |

| Succeeded by | David R. Francis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Michael Hoke Smith September 2, 1855 Newton, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | November 27, 1931 (aged 76) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oakland Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Birdie Cobb |

| Signature | |

Michael Hoke Smith (September 2, 1855 – November 27, 1931) was an American attorney, politician, and newspaper owner who served as United States secretary of the interior (1893–1896), 58th governor of Georgia (1907–1909, 1911), and a United States senator (1911–1920) from Georgia. He was a leader of the progressive movement in the South and in the successful campaign to disenfranchise African American voters in 1907.[1]

Biography

Early years and education

Smith was born in Newton, North Carolina, on September 2, 1855, to Hildreth H. Smith, president of Catawba College, and Mary Brent Hoke.[2] When Smith was 2 years old, his father accepted a position on the faculty of the University of North Carolina, and moved the family to Chapel Hill. Smith attended Pleasant Retreat Academy and was primarily educated by his father. Smith was too young to participate in the Civil War, but his uncle, Confederate General Robert Hoke, fought in the war. In 1868, when the elder Smith lost his position at the university, he moved the family to Atlanta, Georgia, the city that would remain the younger Smith's home for the rest of his life.[2] Smith did not attend law school, but read for the law in association with an Atlanta law firm. He passed the bar examination in 1873, at age seventeen, and became a lawyer in Atlanta.[2]

Law practice

Smith maintained a small office in the James building downtown. His practice began to grow when he began to argue injury suits.[3] As his practice grew, he brought in his brother Burton in 1882, also excellent in front of juries, and they worked together for over 10 years.[4] Their main clients were the many railroad workers injured on the job; three-quarters of the cases they took involved personal injury and they won the bulk of them.[5]

Political service

Smith served as chairman of the Fulton County and State Democratic Conventions and was president of the Atlanta Board of Education. In 1887, Smith bought the Atlanta Journal. His strong support in the Journal for Grover Cleveland during the 1892 presidential election garnered Cleveland's attention and led to a federal job.

Smith was appointed as Secretary of the Interior by Cleveland in 1893.[6] He worked hard to right land patents previously obtained by the railroads, for rationalization of Indian affairs and for the economic development of the South. A staunch defender of Cleveland and his sound money policy, Smith campaigned throughout the country in 1896 for Cleveland candidates.[7] When William Jennings Bryan was selected at the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Smith was in a quandary: could he support the party without supporting the platform? The overwhelming support for silver and Bryan in his home state of Georgia convinced him to try to have it both ways. His newspaper, the Journal, endorsed the candidate but continued to denounce the silver policy. Smith resigned his cabinet post to protect Cleveland.[8]

Smith returned to Atlanta and resumed his lucrative law practice netting around $25,000 per year and slowly rebuilt his local reputation.[9] In April 1900 he sold his interests in the Journal and tried many other investments but the only ones that did well were real estate in the Atlanta area. He was instrumental in organizing the North Avenue Presbyterian Church (which still stands) and was re-elected to the Atlanta Board of Education.[10]

Smith allied himself with Bryan's vice presidential candidate, Populist Tom Watson, one of Georgia's most influential politicians. With Watson's support, he embraced Black disfranchisement calling the races "different, radically different" and supporting separate taxes for Black and white schools calling it "folly to spend the money of white men to give negroes a book education."[11] Watson's support helped Smith win the governorship in 1906. Smith's demagogic diatribes on behalf of white supremacy in the election are considered a primary cause of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot.[12] As governor Smith promoted several Jim Crow laws in a constitutional amendment that required either a literacy test or property ownership for voting, and then adding a grandfather clause exemption for poor whites. This constitutional amendment effectively disenfranchised black Georgians. Smith also supported railroad reform and election reform. After losing the support of Watson,[13] he was defeated in the next election by Joseph M. Brown. Smith was re-elected as governor in 1911.

In 1911 while still governor, he was chosen by the Georgia General Assembly to fill out the term of United States Senator Alexander S. Clay. Smith won re-election in 1914, but was defeated by Tom Watson in 1920. Afterward, Smith practiced law in Washington, DC, and Atlanta.

Death and legacy

Smith died in 1931 and is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, the last surviving member of the Cleveland Cabinet and the second Cleveland Administration.

Hoke Smith High School (1947–1985) once stood at 535 Hill Street SE, in Atlanta. During World War II, a Liberty ship was named the SS Hoke Smith.[14] The Hoke Smith Annex Building on the campus of the University of Georgia was named in honor of the late senator.[15]

References

- ^ Dewey W. Grantham, "Hoke Smith: Progressive Governor of Georgia, 1907-1909." Journal of Southern History 15.4 (1949): 423-440.

- ^ a b c Duncan Maysilles (July 19, 2017). "Hoke Smith (1855–1931)". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ Dewey W. Grantham (March 1, 1967). Hoke Smith and the Politics of the New South. LSU Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8071-0118-6.

- ^ Grantham, p.17

- ^ Grantham, p.21

- ^ Grantham, Dewey W. (November 1949). "Hoke Smith: Progressive Governor of Georgia, 1907-1909". The Journal of Southern History. 15 (4): 423–440. doi:10.2307/2198381. JSTOR 2198381.

- ^ Vinson, John Chalmers; Montgomery, Horace (2010). Georgians in profile : historical essays in honor of Ellis Merton Coulter. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0820335476.

- ^ Grantham, p.110

- ^ Grantham, p.113

- ^ Grantham, p.118

- ^ Michael Perman, The Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908, 288

- ^ Perman, Struggle for Mastery, 288-290.

- ^ Smith, Zachary (2012). "Tom Watson and Resistance to Federal War Policies in Georgia during World War I". Journal of Southern History. 78 (2): 301.

- ^ Kenneth Rogers Photographs. "Launch of the SS Hoke Smith". Atlanta History Center - Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Hoke Smith Annex". University of Georgia. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

External links

- Vanishing Georgia - Photograph of a political rally for the gubernatorial race of 1906, Fitzgerald, Ben Hill County, Georgia, 1906

- United States Congress. "Hoke Smith (id: S000551)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- The Strange Career of Jim Crow by C. Vann Woodward, 2nd edition, (Oxford University Press: 1966) pp. 86–91.