Does cannabis extract obtained from cannabis flowers with maximum allowed residual level of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A have an impact on human safety and health?

Contents

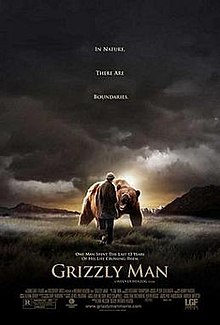

| Grizzly Man | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Werner Herzog |

| Written by | Werner Herzog |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Narrated by | Werner Herzog |

| Cinematography | Peter Zeitlinger |

| Edited by | Joe Bini |

| Music by | Richard Thompson |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Lions Gate Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $4.1 million[2] |

Grizzly Man is a 2005 American documentary film by German director Werner Herzog. It chronicles the life and death of bear enthusiast and conservationist Timothy Treadwell and his girlfriend Amie Huguenard at Katmai National Park, Alaska. The film includes some of Treadwell's own footage of his interactions with brown bears before 2003, and of interviews with people who knew or were involved with Treadwell, in addition to professionals who deal with wild bears.

Treadwell and Huguenard, both from New York, had bonded over their common passion for bears and animal conservation, and she would occasionally accompany him on his trips to the park. Having stayed past the summer season one year, the pair were attacked and killed in the park by a bear on October 5, 2003. The couple's remains were discovered by a patrolling pilot, and an audio recording of the attack was found among the remains; the bear was later encountered and killed by the pilot's rescue team.

The film was co-produced by Discovery Docs and Lions Gate Entertainment. The film's soundtrack was composed by Richard Thompson.

It received widespread acclaim from critics and is now considered to be among the best films of the 2000s and of the 21st century.[3][4]

Synopsis

Herzog used sequences extracted from more than 100 hours of video footage shot by Treadwell during the last five years of his life. He also conducted and filmed interviews with Treadwell's family and friends, as well as bear and nature experts. Park rangers and bear experts commented on statements and actions by Treadwell, such as his repeated claims that he was defending the bears from poachers. A bear researcher clarifies that the incidence of poaching on Kodiak Island was low, but the director of the Alutiiq Museum notes that Treadwell's actions may have put the bears at risk by habituating them to human contact. Treadwell also claimed that he had "gained the trust" of certain bears, sufficient to approach and pet them. A local pilot speculates that the bears were so confused by Treadwell's direct, casual contact that they were not sure how to react to him.

In 2003, Treadwell was camping in Katmai National Park with his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard. Treadwell usually left the park at the end of summer but that year stayed into early October. This put him and Huguenard at greater risk, as bears are aggressive during this period and search for food to store up calories for hibernation during the winter. Herzog speculates that staying later in the season ultimately resulted in the couple's being attacked and killed.

Willy Fulton was the pilot who discovered the few remains of the couple and reported to the National Park Service. He notes that he saw a lone man's arm with a wristwatch, and could not keep the image out of his mind. After an investigation, the coroner and park police gave the wristwatch to Jewel Palovak, an ex-girlfriend of Treadwell. He had bequeathed her his belongings. These included his video camera, which captured an audio record of the attack.

In addition to presenting views from friends and professionals, Herzog narrates and offers his own interpretation of events. He concluded that Treadwell had a sentimental view of nature, thinking he could tame the wild bears. Herzog notes that nature is cold and harsh; Treadwell's view clouded his thinking and led him to underestimate danger, resulting in his death and that of Huguenard.

Palovak gave permission to Herzog to listen to the audio record of the attack. He refrained from making this a part of the film, but was filmed while listening, and showed how this distressed him. Herzog initially advised Palovak to destroy the audio recording rather than listen to it or keep it.

In a later interview, he repudiated his own advice, saying it was:

Stupid ... silly advice born out of the immediate shock of hearing—I mean, it's the most terrifying thing I've ever heard in my life. Being shocked like that, I told her, "You should never listen to it, and you should rather destroy it. It should not be sitting on your shelf in your living room all the time." [But] she slept over it and decided to do something much wiser. She did not destroy it but separated herself from the tape, and she put it in a bank vault.[5]

Production

Treadwell spent thirteen summers in Katmai National Park and Preserve, Alaska. Over time, he believed the bears grew to trust him; they allowed him to approach them and he had touched them. He gained some national notoriety for his association with the bears and founded Grizzly People with his friend Jewel Palovak. They worked to protect bears in national parks by raising awareness.

Park officials repeatedly warned him that his interaction with the bears was unsafe to both him and to the bears. "At best, he's misguided," Deb Liggett, superintendent at Katmai and Lake Clark national parks, told the Anchorage Daily News in 2001. "At worst, he's dangerous. If Timothy models unsafe behavior, that ultimately puts bears and other visitors at risk."

Treadwell filmed his exploits, and used the films to raise public awareness of the problems faced by bears in North America. In October 2003, at the end of his thirteenth visit, he and his girlfriend Amie Huguenard were attacked, killed, and partially eaten by a bear. The events that led to the attack are unknown.

Producer Erik Nelson had begun work on developing a narrative television special based on Treadwell's life and career. However, during a chance encounter with German director Werner Herzog at the Jackson Hole Wildlife Festival, Nelson was persuaded to turn the project into a feature-length documentary and to give Herzog directing duties. With the project being developed as a documentary, they contacted Jewel Palovak in order to use Treadwell's archival footage.

Palovak, co-founder of Grizzly People and a close friend of Treadwell's, had to give her approval for the film to be produced, as she controlled his video archives. The filmmakers had to deal with logistical as well as sentimental factors related to Treadwell's footage of his bear interactions. Grizzly People is a "grassroots organization" concerned with the treatment of bears in the United States. After her friend's death, Palovak was left with control of Grizzly People and Treadwell's 100 hours of archival footage. As his close friend, former girlfriend, and confidante, she had a large emotional stake in the production. She had known Treadwell since 1985 and felt a deep sense of responsibility to her late friend and his legacy.[6]

Palovak said that Treadwell had often discussed his video archives with her. "Timothy was very dramatic," she once said. She quoted Treadwell as saying, "'If I die, if something happens to me, make that movie. You make it. You show 'em.' I thought that Werner Herzog could definitely do that."[6][7]

Release

Grizzly Man premiered at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival and its limited US theatrical release began on August 12, 2005. It was later released on DVD in the United States on December 26, 2005.[8] The Discovery Channel aired Grizzly Man on television on February 3, 2006; its three-hour presentation of the film included a 30-minute companion special that delved deeper into Treadwell's relationship with the bears and addressed controversies related to the film.

The DVD release lacks an interview with Treadwell by David Letterman, which was shown in the original theatrical release. Letterman had joked that Treadwell would be eaten by a bear. The versions televised on the Discovery Channel and Animal Planet both retain this scene.

Response

Box office

Grizzly Man opened on August 12, 2005 in 29 North America venues. It grossed US$269,131 ($9,280 per screen) in its opening weekend, ranking number 26 in the box office.[9] At its widest point, it played at 105 theaters, and made US$3,178,403 in North America during its run, with $882,902 overseas for a worldwide total of $4,061,305.[2]

Critical reception

Upon its North American theatrical release, Grizzly Man was acclaimed by critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 92% score based on 136 reviews, with an average rating of 8/10. The site's consensus states: "Whatever opinion you come to have of the obsessive Treadwell, Herzog has once again found a fascinating subject."[10] Metacritic reports an 87 out of 100 rating based on 35 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[11]

David Denby of The New Yorker said:

Narrating in his extraordinary German-accented English, Herzog is fair-minded and properly respectful of Treadwell's manic self-invention. He even praises Treadwell as a good filmmaker: as Treadwell stands talking in the foreground of the frame, the bears play behind him or scoop up salmon in sparkling water; in other shots, a couple of foxes leap across the grass in the middle of a Treadwell monologue. The footage is full of stunning incidental beauties.[12]

Film critic Roger Ebert, a longtime supporter of Herzog's work, awarded the film four out of four stars.

"I will protect these bears with my last breath", Treadwell says. After he and Amie become the first and only people to be killed by bears in the park, the bear that is guilty is shot dead. Treadwell's watch, still ticking, is found on his severed arm. I have a certain admiration for his courage, recklessness, idealism, whatever you want to call it, but here is a man who managed to get himself and his girlfriend eaten, and you know what? He deserves Werner Herzog.[13]

Charlie Russell, a naturalist who studied bears for many years, lived near them and raised them for a decade in Kamchatka, corresponded with Treadwell and wrote about the film:[14]

Herzog is a skillful filmmaker so a large percentage of those who watch the movie Grizzly Man, overlook Timothy's amazing way with animals even though to me this stands out very strongly. The fact that Timothy spent an incredible 35,000 hours, spanning 13 years, living with the bears in Katmai National Park, without any previous mishap, escapes people completely. Even with his city-kid background, I found myself mesmerized by what he could do with animals.[14]

The film placed at No. 94 on Slant Magazine's best 100 films of the 2000s.[15] In 2021, it was included on Forbes's list of "The Top 150 Greatest Films Of The 21st Century."[16] In 2023, Collider called it the "Best Documentary of the 2000s," with Aiden Bryant writing that it is "a testament to the power of true, dedicated documentary filmmaking. It examines a subject beyond just informing the viewer of who, what, when, where, and why - it extrapolates those questions onto us all. It makes a figure like Treadwell, someone who could easily be a martyr or fool, into someone as complicated as any great protagonist in film. Herzog does something in just over 90 minutes that a million Netflix documentaries never have."[4] The Hollywood Reporter also ranked it at number 43 on its list of the "50 Best Films of the 21st Century (So Far)."[3]

Awards

- Nominated for the Gotham Award for Best Documentary[17]

- Won the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award for Best Documentary/ Non-Fiction Film

- Won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Non-Fiction Film

- Won the San Francisco Film Critics Circle Award for Best Documentary

- Won the Alfred P. Sloan Prize[18] and was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival

- Won the Toronto Film Critics Association Award for Best Documentary

- Won the Anugerah Seri Angkasa 2008 Angkasapuri.

References

- ^ "GRIZZLY MAN (15)". British Board of Film Classification. December 16, 2005. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Grizzly Man (2005)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. November 25, 2005. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Hollywood Reporter Critics Pick the 50 Best Films of the 21st Century (So Far)". The Hollywood Reporter. April 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "This Tragic Man Vs. Nature Film is the Best Documentary of the 2000s". Collider. June 4, 2023.

- ^ Davis, Robert (April 11, 2007). "Werner Herzog: The Tests and Trials of Men". Paste.

- ^ a b "Werner Herzog Film: Home". Wernerherzog.com. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ "Grizzly Man – Feature". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ "Grizzly Man:About This Movie". IGN. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for August 12–14, 2005". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. August 15, 2005. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Grizzly Man (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ "Grizzly Man reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Denby, David (August 8, 2005). "Loners". The New Yorker.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 12, 2005). "Grizzly Man". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ a b Russell, Charlie (February 21, 2006). Letters from Charlie. cloudline.org.

- ^ "Best of the Aughts: Film". Slant Magazine. February 7, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Hughes, Mark. "The Top 150 Greatest Films Of The 21st Century". Forbes. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ Past Recipients – IFP Gotham Awards

- ^ Sundance Film Festival 2005 - MUBI

Further reading

- Conesa-Sevilla, J. (2008). "Walking With Bears: An Ecopsychological Study of Timothy (Dexter) Treadwell", The Trumpeter, 24, 1, 136–150.

- Dewberry, Eric. "Conceiving Grizzly Man through the 'Powers of the False' ", Scope (Nottingham University), 2008