Design of generalized search interfaces for health informatics

Contents

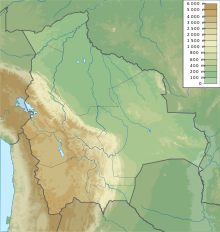

Tourism in Bolivia is one of the key economic sectors of the country. According to data from the National Institute of Statistics of Bolivia (INE), there were over 1.24 million tourists that visited the country in 2020, making Bolivia the ninth most visited country in South America.[1][2][3]

People have visited Bolivia for centuries in the form of movement of people during the pre-Inca and Inca period, in which wealthy groups within moved outside their habitual residence across the vast expanse of the Inca empire. that stretched 2,500 from Ecuador in the north to Chile in the south.[4]

Bolivia is a country with great tourism potential, with many attractions, due to its diverse culture, geographic regions, rich history and food. In particular, the salt flats at Uyuni are a major attraction.

History

People have visited Bolivia for centuries. During the pre-Incan and Incan period, privileged social groups could move away from their place of residence and settle in new towns. The Inca road system, a vast network of carefully engineered roads that connected settlements in present day Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, facilitated the movement of people and goods across South America.[5] During the colonial era, several expeditions were carried out in Bolivia as a way to seek resources and wealth and expand the Spanish domain.

Tourism in Bolivia was formalized as an official entity in 1930 during the presidency of David Toro.[6] From that moment on, the Bolivian government began to regulate tourism within the country, to ensure the care of tourist attractions and to provide assistance to foreign tourists arriving in Bolivia.

Organized tourism in Bolivia began in the 1940s. One of the precursors of this activity was Darius Morgan, a Romanian entrepreneur who came to Bolivia working for the Swedish company Ericsson.[7] When touring the Altiplano region around Lake Titicaca, Morgan had been fascinated by the scenic beauty of the area, which was not frequently visited at the time. Morgan eventually established the first travel agency in Bolivia and began offering organized tours to Lake Titicaca. Given the lack of accommodation establishments in the lake region, tourists stayed in camps with tents set up and food prepared in advance. However, Morgan managed to spread the word about the natural beauty of the region, impacting the arrival of more foreign tourists who wanted to visit the highest navigable lake in the world. In 1886, Darius Morgan was awarded the Order of the Condor of the Andes, the highest distinction in Bolivia, for his contribution to the development of tourism in the country.[8]

World Heritage Sites in Bolivia

Bolivia has seven World Heritage Sites listed by UNESCO.[9] They constitute important tourist attractions due to their historical and cultural legacy. Bolivia was among the first countries that ratified folklore as a cultural heritage at the UNESCO Convention of 1972, giving rise to profound debates, resulting in the creation of the "Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage" in 2003.[10]

- The city of Potosí (1987): Known as Villa Imperial de Potosí (spanish for Imperial City of Potosí), was the first site to be recognized by UNESCO in Bolivia, due to its contribution to universal history, often considered one of the birthplaces of early capitalism. It was one of the world's most important mining sites during the colonial times, and a source of wealth for the Spanish Empire.[11] The city is also considered the cradle of the Andean baroque architectural style. During the 16th century, It was considered the world's largest industrial complex and its population grew to more than 200,000 inhabitants. The Cerro Rico, discovered by the Spanish in 1545, contained what was once the largest silver mine in the world, contributing with 60% of the world's silver exploitation at the time.[12] The city is known for its colonial-style neighborhoods and features important cultural sites such as the historic National Mint of Bolivia and the Church of San Lorenzo de Carangas.

- Fort Samaipata (1998): Located in the department of Santa Cruz, it is a pre-Inca archaeological site of Chané origin, located a few kilometers from the town of Samaipata. The fort consists of two parts, the hill with its numerous engravings, believed to be a ceremonial center, and the area south of the hill, which housed the administrative and residential center of the Chané civilization. The great rock is considered the largest carved stone in the world.[13] It served as an astronomical and cosmic observatory for the Chané people, and hosted religious and ceremonial functions towards the moon.[14]

- The Historical City of Sucre (1991): Founded by the Spanish in the first half of the 16th century, Sucre is the constitutional capital of Bolivia. The city features well preserved buildings that show an architectural mixture of Spanish baroque with the assimilation of local traditions and styles. in Latin America through the assimilation of local traditions and styles imported from Europe.[15] Established in 1538 as Villa de la Plata of the new Toledo, the city was the cultural, judicial and religious center of the Region of the Royal Audience of Charcas for several years. In 1839, the city was renamed after Antonio José de Sucre, a Bolivian revolutionary. The University of San Francisco Xavier, founded in 1624, is the oldest university in Bolivia and the second oldest in Latin America.[16]

- The Jesuit missions of Chiquitos (1990): Between 1691 and 1760, the Society of Jesus founded a series of "villages of Indians" in order to Christianize the indigenous population. Largely inspired by the "ideal cities" imagined by the humanist philosophers of the sixteenth century in the territory of Chiquitos, in eastern Bolivia, the Jesuits and their indigenous positions combined European architecture with local traditions. The six historical missions that remain intact are San Xavier, San Rafael de Velasco, San José de Chiquitos, Concepción, San Miguel de Velasco and Santa Ana de Velasco. These today make up a living but vulnerable heritage in the territory of the Chiquitanía and are the only active missions in all of South America.[17]

- The ruins of the city of Tiwanaku (2000): Located near the southern shore of Lake Titicaca in the Bolivian Altiplano, it is considered one of the earliest settlements of human civilization, and one of the oldest in the Americas, it existed for 27 centuries. The city was the spiritual and political center of the Tiwanaku culture and began small settlement and later became a planned city between 400 d. C. and 900 d. C. The main buildings in Tiwanaku include the pyramid of Akapana, a huge staggered adobe pyramid and the temple of Kalasasaya, a sacred site with a structure based on sandstone columns and cut sillars, and featuring standing gargoyles with drainage systems for rainwater.[18] Important monuments include the Gate of the Sun, the Gate of the Moon, and the famous monoliths that feature numerous iconographies and mysterious inscriptions with astronomical meanings.

Madidi National Park in the Amazon basin is a popular destination for ecotourism in Bolivia - Noel Kempff Mercado National Park (2000): Covering an area of 1.5 million hectares, it is one of the largest and most intact natural reserves in the Amazon basin.[19] It is Bolivia's only natural heritage site. The park has various habitats that include mountainous forests and savannas. The flora is rich in diversity of endemic vegetation. It contains about 2,700 species of plants recorded, though it is estimated that there could be about 4,000 species of undiscovered plants.[20] Additionally, the park contains approximately 1,142 species of vertebrates, representing 21% of all species in South America.[21]

- The Inca Road System (2014): Was the most extensive and advanced transportation system in pre-Columbian South America.[22] The network was composed of formal roads carefully planned, engineered, built, marked and maintained; paved where necessary, with stairways to gain elevation, bridges and accessory constructions such as retaining walls, and water drainage systems. At its maximum extension, it connected regions and urban centers in current Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina with a network that exceeded 30,000 kilometers in length. The road system allowed for the transfer of information, goods, soldiers and persons, without the use of wheels, within the Tawantinsuyu or Inca Empire throughout a territory covering almost 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi)[23] and inhabited by about 12 million people.[24]

- Image gallery of the World Heritage sites of Bolivia

-

Potosí with the Cerro Rico in the background

-

Church of the Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos in Concepción, Santa Cruz

-

The temple of Kalasasaya in Tiwanaku

-

The Inca road system

Destinations

- Lake Titicaca, the world's highest navigable lake.[25]

Number of foreign tourists in Bolivia - The Isla del Sol, the sacred place of the Incas and birthplace of the founders of the Inca Empire, Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo

- The Isla de la Luna, another sacred place of the Incas near the Isla del Sol.

- Copacabana, a small town on the shores of Titicaca, home to the Virgin of Copacabana, crowned queen of Bolivia.

- The Andes, the longest mountain range in the world, spanning the entire continent, which include:

- The ski slope containing the highest restaurant in the world,[26] called Chacaltaya.

- The highest mountain in the country: Nevado Sajama, with the highest forest in the world.

- The salt flats of Uyuni and Coipasa, the largest salt flats in the world.

- Bolivia also is the only country in the world in having the only hotel totally fabricated of salt, found in the Uyuni.

- The lakes Green lake and Red Lagoon, the sanctuary of the Andean flamingos with one of the largest active volcanoes in the world, the Licancabur.[27]

- The historic cities of:

- Potosí with its Cerro Rico, formerly the largest deposit of silver in the world.

- Sucre, the constitutional capital city of Bolivia, and The City of Four Names, which is home to one of the oldest universities in the Americas.

- Casa de la Libertad, where the Declaration of Independence of Bolivia remains.

- La Recoleta, a Franciscan monastery, one of the first in the city.

- Cal Orcko is a paleontological site, found in the quarry of a cement factory, in the Department of Chuquisaca.

- Ruins of Portugalete

- Carnaval de Oruro

- Abandoned mining sites, e.g. Pulacayo and Uncía

- Tupiza with the graves of Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid

- Yungas

- Coroico, Center of Afro-Bolivian culture

- Carretera de la muerte, today a popular cycling route

- Amazon Basin:

- The Madidi National Park, considered by National Geographic to be one of the most imprescidible places to visit in the world[citation needed], is part of the circuit of tourism in Bolivia.

- The Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, located in the department of SantHeritage, which was declared a World Heritage Site on 13 December 1991. The camps Flor de Oro (the principal camp) and Los Fierros have tourist infrastructure.

- Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos

See also

- Visa policy of Bolivia

- List of national parks of Bolivia

- Visitor attractions in Bolivia (category)

- Aquicuana Reserve

- Lake Titicaca

- Uyuni

References

- ^ "International tourism, number of arrivals - Bolivia". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Estadísticas de flujo de visitantes". Instituto Nacional de Estadística (in Spanish). Ministerio de Planidicación del Desarrollo. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "The 11 Most Visited Countries in South America". Worldly Adventurer. 10 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Chopitea Chávez, Iván (31 May 2010). "Historia del turismo en Bolivia" [History of tourism in Bolivia]. gestiopolis.com (in Spanish). Bogota, Colombia. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark. "The Inca Road System". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Historia del Turismo en Bolivia" [History of Tourism in Bolivia]. Scribd (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Darius Morgan". Darius Morgan. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Balance de Hotelería 2018" (PDF). Nueva economía. 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Bolivia (Plurinational State of)". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage" (pdf). UNESCO. Bali, Indonesia (published 22 November 2011). 2011.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (21 March 2016). "How silver turned Potosí into 'the first city of capitalism'". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Avilés, Giselle M. (22 August 2022). "A short story about Potosi—the largest South American silver mine—in the Library's Collections (Part 1)". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Bolivia (Plurinational State of). Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Site. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Hoekstra, Kyle (8 September 2021). "El Fuerte de Samaipata". History Hit. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "Bolivia (Plurinational State of). Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Site. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Sucre | Bolivia, Map, Population, & Elevation". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ Rodríguez, Andrés (30 September 2018). "La cultura viva de las Misiones Jesuíticas de la Chiquitania se conserva en Bolivia" [The live culture of the Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitanía are preserved in Bolivia]. El País (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Tiwanaku | Pre-Inca Civilization, Bolivia | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ UNEP-WCMC (22 May 2017). "NOEL KEMPFF MERCADO NATIONAL PARK". World Heritage Datasheet. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ Burbridge, Rachel E.; Mayle, Francis E.; Killeen, Timothy J. (1 March 2004). "Fifty-thousand-year vegetation and climate history of Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Bolivian Amazon". Quaternary Research. 61 (2): 215–230. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2003.12.004. ISSN 0033-5894.

- ^ "Noel Kempff National Park". Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2002). The Incas. Blackwell Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-631-17677-2.

- ^ Raffino, Rodolfo et al. Rumichaca: el puente inca en la cordillera de los Chichas (Tarija, Bolivia) – in "Arqueologia argentina en los incios de un nevo siglo" pags 215 to 223

- ^ "The Four Suyus, Engineering the Inka Empire". National Museum of the American Indian. Smithsonian Institution. 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Highest restaurant". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Vitry, Christian (September 2020). "Los Caminos Ceremoniales en los Apus del Tawantinsuyu". Chungará (Arica). 52 (3): 509–521. doi:10.4067/S0717-73562020005001802. ISSN 0717-7356.

External links

- Tourism in Bolivia

Media related to Tourism in Bolivia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tourism in Bolivia at Wikimedia Commons