Design of generalized search interfaces for health informatics

Contents

| Narmer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menes(?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Verso of the Narmer Palette | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Somewhere in between 3273–2987 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ka? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Hor-Aha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Uncertain: possibly Neithhotep | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Uncertain: probably Hor-Aha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Ka?, Scorpion II? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Chambers B17 and B18, Umm El Qa'ab | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 1st dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Narmer (Ancient Egyptian: nꜥr-mr, may mean "painful catfish", "stinging catfish", "harsh catfish", or "fierce catfish;"[1][2][3] fl. c. 3150 BC[4]) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period, whose reign began at a date estimated to fall in the range 3273–2987 BC.[5] He was the successor to the Protodynastic king Ka. Many scholars consider him the unifier of Egypt and founder of the First Dynasty, and in turn the first king of a unified Egypt. He also had a prominently noticeable presence in Canaan, compared to his predecessors and successors. Neithhotep is thought to be his queen consort or his daughter.

A majority of Egyptologists believe that Narmer was the same person as Menes.[a][7][8][9]

Historical identity

Although highly interrelated, the questions of "who was Menes?" and "who unified Egypt?" are actually two separate issues. Narmer is often credited with the unification of Egypt by means of the conquest of Lower Egypt by Upper Egypt. Menes is traditionally considered the first king/pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, and is identified by the majority of Egyptologists as the same person as Narmer – although a vigorous debate also proposes identification with Hor-Aha, Narmer's successor, as a primary alternative.[b]

The issue is confusing because "Narmer" is a Horus name while "Menes" is a Sedge and Bee name (personal or birth name). All of the King Lists which began to appear in the New Kingdom era list the personal names of the kings, and almost all begin with Menes, or begin with divine and/or semi-divine rulers, with Menes as the first "human king". The difficulty is aligning the contemporary archaeological evidence which lists Horus Names with the King Lists that list personal names.

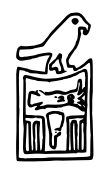

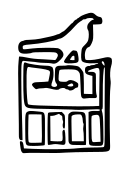

Two documents have been put forward as proof either that Narmer was Menes or alternatively Hor-Aha was Menes. The first is the "Naqada Label" found at the site of Naqada, in the tomb of Queen Neithhotep, often assumed to have been the mother of Horus Aha.[11] The label shows a serekh of Hor-Aha next to an enclosure inside of which are symbols that have been interpreted by some scholars as the name "Menes". The second is the seal impression from Abydos that alternates between a serekh of Narmer and the chessboard symbol, "mn", which is interpreted as an abbreviation of Menes. Arguments have been made with regard to each of these documents in favour of Narmer or Hor-Aha being Menes, but in neither case is the argument conclusive.[c]

The second document, the seal impression from Abydos, shows the serekh of Narmer alternating with the gameboard sign (mn), together with its phonetic complement, the n sign, which is always shown when the full name of Menes is written, again representing the name "Menes". At first glance, this would seem to be strong evidence that Narmer was Menes.[15] However, based on an analysis of other early First Dynasty seal impressions, which contain the name of one or more princes, the seal impression has been interpreted by other scholars as showing the name of a prince of Narmer named Menes, hence Menes was Narmer's successor, Hor-Aha, and thus Hor-Aha was Menes.[16] This was refuted by Cervelló-Autuori 2005, pp. 42–45; but opinions still vary, and the seal impression cannot be said to definitively support either theory.[17]

Two necropolis sealings, found in 1985 and 1991 in Abydos (Umm el-Qa'ab), in or near the tombs of Den[19] and Qa'a,[20] show Narmer as the first king on each list, followed by Hor-Aha. The Qa'a sealing lists all eight of the kings of what scholars now call the First Dynasty in the correct order, starting with Narmer. These necropolis sealings are strong evidence that Narmer was the first king of the First Dynasty, hence the same person as Menes.[21]

Name

The complete spelling of Narmer's name consists of the hieroglyphs for a catfish (nꜥr)[d] and a chisel (mr), hence the reading "Narmer" (using the rebus principle). This word is sometimes translated as "raging catfish".[24] However, there is no consensus on this reading. Other translations of the adjective before "catfish" include "angry", "fighting", "fierce", "painful", "furious", "bad", "evil", "biting", "menacing", and "stinging".[1][2][3] Some scholars have taken entirely different approaches to reading the name that do not include "catfish" in the name at all,[25][26][27] but these approaches have not been generally accepted.

Rather than incorporating both hieroglyphs, Narmer's name is often shown in an abbreviated form with just the catfish symbol, sometimes stylized, even, in some cases, represented by just a horizontal line.[28] This simplified spelling appears to be related to the formality of the context. In every case that a serekh is shown on a work of stone or an official seal impression, it has both symbols. But, in most cases, where the name is shown on a piece of pottery or a rock inscription, just the catfish, or a simplified version of it appears.

Two alternative spellings of Narmer's name have also been found. On a mud sealing from Tarkhan, the symbol for the ṯꜣj-bird (Gardiner sign G47 "duckling") has been added to the two symbols for "Narmer" within the serekh. This has been interpreted as meaning "Narmer the masculine";[29] however, according to Ilona Regulski,[30] "The third sign (the [ṯꜣj]-bird) is not an integral part of the royal name since it occurs so infrequently." Godron[31] suggested that the extra sign is not part of the name, but was put inside the serekh for compositional convenience.

In addition, two necropolis seals from Abydos show the name in a unique way: While the chisel is shown conventionally where the catfish would be expected, there is a symbol that has been interpreted by several scholars as an animal skin.[32] According to Dreyer, it is probably a catfish with a bull's tail, similar to the image of Narmer on the Narmer Palette in which he is shown wearing a bull's tail as a symbol of power.[33]

Reign

The date commonly given for the beginning of Narmer's reign is c. 3100 BC.[34][35] Other mainstream estimates, using both the historical method and radiocarbon dating, are in the range c. 3273–2987 BC.[e]

Unification of Upper and Lower Egypt

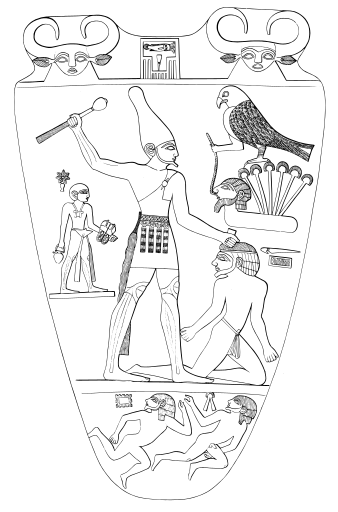

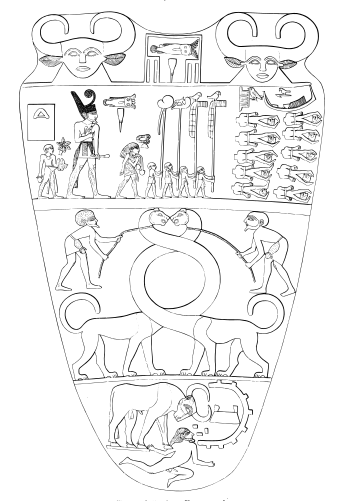

The famous Narmer Palette, discovered by James E. Quibell in the 1897–1898 season at Hierakonpolis,[36] shows Narmer wearing the crown of Upper Egypt on one side of the palette, and the crown of Lower Egypt on the other side, giving rise to the theory that Narmer unified the two lands.[37] Since its discovery, however, it has been debated whether the Narmer Palette represents an actual historic event or is purely symbolic.[f] Of course, the Narmer Palette could represent an actual historical event while at the same time having a symbolic significance.

In 1993, Günter Dreyer discovered a "year label" of Narmer at Abydos, depicting the same event that is depicted on the Narmer Palette. In the First Dynasty, years were identified by the name of the king and an important event that occurred in that year. A "year label" was typically attached to a container of goods and included the name of the king, a description or representation of the event that identified the year, and a description of the attached goods. This year label shows that the Narmer Palette depicts an actual historical event.[38] Support for this conclusion (in addition to Dreyer) includes Wilkinson[39] and Davies & Friedman.[40] Although this interpretation of the year label is the dominant opinion among Egyptologists, there are exceptions including Baines[41] and Wengrow.[42]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Egypt was at least partially unified during the reigns of Ka and Iry-Hor (Narmer's immediate predecessors), and perhaps as early as Scorpion I. Tax collection is probably documented for Ka[45] and Iry-Hor.[46] The evidence for a role for Scorpion I in Lower Egypt comes from his tomb Uj in Abydos (Upper Egypt), where labels were found identifying goods from Lower Egypt.[47] These are not tax documents, however, so they are probably indications of trade rather than subjugation. There is a substantial difference in the quantity and distribution of inscriptions with the names of those earlier kings in Lower Egypt and Canaan (which was reached through Lower Egypt), compared to the inscriptions of Narmer. Ka's inscriptions have been found in three sites in Lower Egypt and one in Canaan.[48] Iry-Hor inscriptions have also been found in two sites in Lower Egypt and one in Canaan.[48][49] This must be compared to Narmer, whose serekhs have been found in ten sites in Lower Egypt and nine sites in Canaan (see discussion in "Tomb and Artefacts" section). This demonstrates a qualitative difference between Narmer's role in Lower Egypt compared to his two immediate predecessors. There is no evidence in Lower Egypt of any Upper Egyptian king's presence before Iry-Hor. The archaeological evidence suggest that the unification began before Narmer, but was completed by him through the conquest of a polity in the north-west Delta as depicted on the Narmer Palette.[50]

The importance that Narmer attached to his "unification" of Egypt is shown by the fact that it is commemorated not only on the Narmer Palette, but on a cylinder seal,[51] the Narmer Year Label,[38] and the Narmer Boxes;[52] and the consequences of the event are commemorated on the Narmer Macehead.[53] The importance of the unification to ancient Egyptians is shown by the fact that Narmer is shown as the first king on the two necropolis seals, and under the name Menes, the first king in the later King Lists. Although there is archaeological evidence of a few kings before Narmer, none of them are mentioned in any of those sources. It can be accurately said that from the point of view of Ancient Egyptians, history began with Narmer and the unification of Egypt, and that everything before him was relegated to the realm of myth.

Peak of Egyptian presence in Canaan

According to Manetho (quoted in Eusebius (Fr. 7(a))), "Menes made a foreign expedition and won renown." If this is correct (and assuming it refers to Narmer), it was undoubtedly to the land of Canaan where Narmer's serekh has been identified at nine different sites. An Egyptian presence in Canaan predates Narmer, but after about 200 years of active presence in Canaan,[54] Egyptian presence peaked during Narmer's reign and quickly declined afterwards. The relationship between Egypt and Canaan "began around the end of the fifth millennium and apparently came to an end sometime during the Second Dynasty when it ceased altogether."[55] It peaked during Dynasty 0 through the reign of Narmer.[56] Dating to this period are 33 Egyptian serekhs found in Canaan,[57] among which 20 have been attributed to Narmer. Prior to Narmer, only one serekh of Ka and one inscription with Iry-Hor's name have been found in Canaan.[58] The serekhs earlier than Iry-Hor are either generic serekhs that do not refer to a specific king, or are for kings not attested in Abydos.[56] Indicative of the decline of Egyptian presence in the region after Narmer, only one serekh attributed to his successor, Hor-Aha, has been found in Canaan.[56] Even this one example is questionable, Wilkinson does not believe there are any serekhs of Hor-Aha outside Egypt[59] and very few serekhs of kings for the rest of the first two dynasties have been found in Canaan.[60]

The Egyptian presence in Canaan is best demonstrated by the presence of pottery made from Egyptian Nile clay and found in Canaan,[g] as well as pottery made from local clay, but in the Egyptian style. The latter suggests the existence of Egyptian colonies rather than just trade.[62]

The nature of Egypt's role in Canaan has been vigorously debated, between scholars who suggest a military invasion[63] and others proposing that only trade and colonization were involved. Although the latter has gained predominance,[62][64] the presence of fortifications at Tell es-Sakan dating to Dynasty 0 through early Dynasty 1 period, and built almost entirely using an Egyptian style of construction, demonstrate that there must have also been some kind of Egyptian military presence.[65]

Regardless of the nature of Egypt's presence in Canaan, control of trade to (and through) Canaan was important to Ancient Egypt. Narmer probably did not establish Egypt's initial influence in Canaan by a military invasion, but a military campaign by Narmer to re-assert Egyptian authority, or to increase its sphere of influence in the region, is certainly plausible. In addition to the quote by Manetho, and the large number of Narmer serekhs found in Canaan, a recent reconstruction of a box of Narmer's by Dreyer may have commemorated a military campaign in Canaan.[66] It may also represent just the presentation of tribute to Narmer by Canaanites.[66]

Neithhotep

Narmer and Hor-Aha's names were both found in what is believed to be Neithhotep's tomb, which led Egyptologists to conclude that she was Narmer's queen and mother of Hor-Aha.[67] Neithhotep's name means "Neith is satisfied". This suggests that she was a princess of Lower Egypt (based on the fact that Neith is the patron goddess of Sais in the Western Delta, exactly the area Narmer conquered to complete the unification of Egypt), and that this was a marriage to consolidate the two regions of Egypt.[67] The fact that her tomb is in Naqada, in Upper Egypt, has led some to the conclusion that she was a descendant of the predynastic rulers of Naqada who ruled prior to its incorporation into a united Upper Egypt.[68] It has also been suggested that the Narmer Macehead commemorates this wedding.[69] However, the discovery in 2012 of rock inscriptions in Sinai by Pierre Tallet[70] raise questions about whether she was really Narmer's wife.[h] Neithhotep is probably the earliest non-mythical woman in history whose name is known to us today.[72]

Tomb and artifacts

Tomb

Narmer's tomb in Umm el-Qa'ab near Abydos in Upper Egypt consists of two joined chambers (B17 and B18), lined in mud brick. Although both Émile Amélineau and Petrie excavated tombs B17 and B18, it was only in 1964 that Kaiser identified them as being Narmer's.[73][i] Narmer's tomb is located next to the tombs of Ka, who likely ruled Upper Egypt just before Narmer, and Hor-Aha, who was his immediate successor.[j]

As the tomb dates back more than 5,000 years, and has been pillaged, repeatedly, from antiquity to modern times, it is amazing that anything useful could be discovered in it. Because of the repeated disturbances in Umm el-Qa'ab, many articles of Narmer's were found in other graves, and objects of other kings were recovered in Narmer's grave. However, Flinders Petrie during the period 1899–1903,[76][77] and, starting in the 1970s, the German Archaeological Institute (DAI)[k] have made discoveries of the greatest importance to the history of Early Egypt by their re-excavation of the tombs of Umm el-Qa'ab.

Despite the chaotic condition of the cemetery, inscriptions on both wood and bone, seal impressions, as well as dozens of flint arrowheads were found. (Petrie says with dismay that "hundreds" of arrowheads were discovered by "the French", presumably Amélineau. What happened to them is not clear, but none ended up in the Cairo Museum.[78]) Flint knives and a fragment of an ebony chair leg were also discovered in Narmer's tomb, all of which might be part of the original funerary assemblage. The flint knives and fragment of a chair leg were not included in any of Petrie's publications, but are now at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology (University College London), registration numbers UC35679, UC52786, and UC35682. According to Dreyer,[33] these arrowheads are probably from the tomb of Djer, where similar arrowheads were found.[79]

It is likely that all of the kings of Ancient Egypt buried in Umm el-Qa'ab had funerary enclosures in Abydos' northern cemetery, near the cultivation line. These were characterized by large mud brick walls that enclosed space in which funerary ceremonies are believed to have taken place. Eight enclosures have been excavated, two of which have not been definitely identified.[80][81] While it has yet to be confirmed, one of these unidentified funerary enclosures may have belonged to Narmer.[l]

Artifacts

Narmer is well attested throughout Egypt, southern Canaan and Sinai: altogether 98 inscriptions at 26 sites.[m] At Abydos and Hierakonpolis Narmer's name appears both within a serekh and without reference to a serekh. At every other site except Coptos, Narmer's name appears in a serekh. In Egypt, his name has been found at 17 sites:

- 4 in Upper Egypt: Hierakonpolis,[87] Naqada,[88][89] Abydos, [76][77] and Coptos[90][91]

- 10 in Lower Egypt: Tarkhan,[92][93] Helwan,[94][95] Zawyet el'Aryan,[96] Tell Ibrahim Awad,[97] Ezbet el-Tell,[98] Minshat Abu Omar,[99][100] Saqqara,[101][102] Buto,[103] Tell el-Farkha,[104][105] and Kafr Hassan Dawood[106]

- 1 in the Eastern Desert: Wadi el-Qaash[107]

- 2 in the Western Desert: Kharga Oasis[108][109] and Gebel Tjauti[110][111]

During Narmer's reign, Egypt had an active economic presence in southern Canaan. Pottery sherds have been discovered at several sites, both from pots made in Egypt and imported to Canaan and others made in the Egyptian style out of local materials. Twenty serekhs have been found in Canaan that may belong to Narmer, but seven of those are uncertain or controversial. These serekhs came from eight different sites: Tel Arad,[112][113] En Besor (Ein HaBesor),[114][115] Tell es-Sakan,[116][117] Nahal Tillah (Halif Terrace),[118] Tel Erani (Tel Gat),[119][120] Small Tel Malhata,[121][122] Tel Ma'ahaz,[123] and Tel Lod,[124]

Narmer's serekh, along with those of other Predynastic and Early Dynastic kings, has been found at the Wadi 'Ameyra in the southern Sinai, where inscriptions commemorate Egyptian mining expeditions to the area.[125][126]

Nag el-Hamdulab

First recorded at the end of the 19th century, an important series of rock carvings at Nag el-Hamdulab near Aswan was rediscovered in 2009, and its importance only realized then.[127][128][129] Among the many inscriptions, tableau 7a shows a man wearing a headdress similar to the White Crown of Upper Egypt and carrying a scepter. He is followed by a man with a fan. He is then preceded by two men with standards, and accompanied by a dog. Apart from the dog motif, this scene is similar to scenes on the Scorpion Macehead and the recto of the Narmer Palette. The man, equipped with pharaonic regalia (the crown and scepter), can clearly be identified as a king. Although no name appears in the tableau, Darnell[128] attributes it to Narmer, based on the iconography, and suggests that it might represent an actual visit to the region by Narmer for a "Following of Horus" ritual. In an interview in 2012, Gatto[130] also describes the king in the inscription as Narmer. However, Hendricks (2016) places the scene slightly before Narmer, based, in part on the uncharacteristic absence of Narmer's royal name in the inscription.

Popular culture

- The First Pharaoh (The First Dynasty Book 1) by Lester Picker is a fictionalized biography of Narmer. The author consulted with Egyptologist Günter Dreyer to achieve authenticity.[131]

- Murder by the Gods: An Ancient Egyptian Mystery by William G. Collins is a thriller about Prince Aha (later king Hor-Aha), with Narmer included in a secondary role.[132]

- Pharaoh: The Boy who Conquered the Nile by Jackie French is a children's book (ages 10–14) about the adventures of Prince Narmer.[133]

- The Third Gate by Lincoln Child is the third book in the Jeremy Logan series and revolves primarily around the discovery and exploration of a fictional secret burial place of Narmer.

- Warframe uses Narmer's name for a faction added in The New War update that shares some similarities to the pharaoh's reign.[134]

- In The Kane Chronicles by Rick Riordan, one of siblings Carter and Sadie's parents comes from Narmer's lineage, the other from Ramses the Great (book one, The Red Pyramid, page 195).

Gallery

-

A mud jar sealing indicating that the contents came from the estate of Narmer. Originally from Tarkhan, now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Pottery sherd inscribed with the serekh and name of Narmer, on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Incised inscription on a vessel found at Tarkhan (tomb 414), naming Narmer; Petrie Museum UC 16083

-

Alabaster statue of a baboon divinity with the name of Narmer inscribed on its base, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin

-

Drawing of Narmer serekh on pottery vessel with stylized catfish and without chisel or falcon, copyright Kafr Hassan Dawood Mission

-

Photograph of sherd showing Narmer serekh from Nahal Tillah without the chisel sign to spell his name, used with permission of copyright holder, Thomas E. Levy, Levantine and Cyber-Archaeology Laboratory, UC San Diego

See also

Notes

- ^ Egyptologists have long debated whether Menes was the same person as Narmer or Hor-Aha, Narmer's successor. A 2014 study by Thomas C. Heagy published in the Egyptological journal Archéo-Nil compiled a list of 69 Egyptologists who took either position. Forty-one of them have concluded that Menes was Narmer, while 31 have concluded that Menes was Hor-Aha. Three Egyptologists—Flinders Petrie, Kurt Sethe and Stan Hendrickx—on the list have first concluded that Menes was Hor-Aha, but later concluded that Menes was Narmer.[6]

- ^ The question of who was Menes—hence, who was the first king of the First Dynasty has been hotly debated. Since 1897, 70 different authors have taken an opinion on whether it is Narmer or Aha.[6] Most of these are only passing references, but there have been several in depth analyses on both sides of the issues. Recent discussions in favor of Narmer include Kinnaer 2001, Cervelló-Autuori 2005, and Heagy 2014. Detailed discussions in favor of Aha include Helck 1953, Emery 1961, pp. 31–37, and Dreyer 2007. For the most part, English speaking authors favor Narmer, while German speaking authors favor Hor-Aha. The most important evidence in favor of Narmer are the two necropolis seal impressions from Abydos, which list Narmer as the first king. Since the publication of the first of the necropolis sealings in 1987, 28 authors have published articles identifying Narmer with Menes compared to 14 who identify Narmer with Hor-Aha.

- ^ In the upper right hand quarter of the Naqada label is a serekh of Hor-Aha. To its right is a hill-shaped triple enclosure with the "mn" sign surmounted by the signs of the "two ladies", the goddesses of Upper Egypt (Nekhbet) and Lower Egypt (Wadjet). In later contexts, the presence of the "two ladies" would indicate a "nbty" name (one of the five names of the king). Hence, the inscription was interpreted as showing that the "nbty" name of Hor-Aha was "Mn" short for Menes.[12] An alternative theory is that the enclosure was a funeral shrine and it represents Hor-Aha burying his predecessor, Menes. Hence Menes was Narmer.[13] Although the label generated a lot of debate, it is now generally agreed that the inscription in the shrine is not a king's name, but is the name of the shrine "The Two Ladies Endure," and provide no evidence for who Menes was.[14]

- ^ Although the catfish portrayed in Narmer's name has sometimes been described as an "electric catfish", based on its fin configuration, it is actually of the non-electric Heterobranchus genus.[23]

- ^ Establishing absolute dating for Ancient Egypt relies on two different methods, each of which is problematic. As a starting point, the Historical Method makes use of astronomical events that are recorded in Ancient Egyptian texts, which establishes a starting point in which an event in Egyptian history is given an unambiguous absolute date. "Dead reckoning"—adding or subtracting the length of each king's reign (based primarily on Manetho, the Turin King List, and the Palermo Stone) is then used until one gets to the reign of the king in question. However, there is uncertainty about the length of reigns, especially in the Archaic Period and the Intermediate Periods. Two astrological events are available to anchor these estimates, one in the Middle Kingdom and one in the New Kingdom (for a discussion of the problems in establishing absolute dates for Ancient Egypt, see Shaw 2000a, pp. 1–16). Two estimates based on this method are: Hayes 1970, p. 174, who gives the beginning of the reign of Narmer/Menes as 3114 BC, which he rounds to 3100 BC; and Krauss & Warburton 2006, p. 487, who places the ascent of Narmer to the throne of Egypt as c. 2950 BC. Several estimates of the beginning of the First Dynasty assume that it began with Hor-Aha. Setting aside the question of whether the First Dynasty began with Narmer or Hor-Aha, to calculate the beginning of Narmer's reign from these estimates, they must be adjusted by the length of Narmer's reign. Unfortunately, there are no reliable estimates of the length of Narmer's reign. In the absence of other evidence, scholars use Manetho's estimate of the length of the reign of Menes, i.e. 62 years. If one assumes that Narmer and Menes are the same person, this places the date for the beginning of Narmer's reign at 62 years earlier than the date for the beginning of the First Dynasty given by the authors who associate the beginning of the First Dynasty with the start of Hor-Aha's reign. Estimates of the beginning of Narmer's reign calculated in this way include von Beckerath 1997, p. 179 (c. 3094–3044 BC); Helck 1986, p. 28 (c. 2987 BC); Kitchen 2000, p. 48 (c. 3092 BC), and Shaw 2000b, p. 480 (c. 3062 BC). Considering all six estimates suggests a range of c. 3114 – 2987 BC based on the Historical Method. The exception to the mainstream consensus, is Mellaart 1979, pp. 9–10 who estimates the beginning of the First Dynasty to be c. 3400 BC. However, since he reached this conclusion by disregarding the Middle Kingdom astronomical date, his conclusion is not widely accepted. Radiocarbon Dating has, unfortunately, its own problems: According to Hendrickx 2006, p. 90, "the calibration curves for the (second half) of the 4th millennium BC show important fluctuations with long possible data ranges as a consequence. It is generally considered a 'bad period' for Radiocarbon dating." Using a statistical approach, including all available carbon 14 dates for the Archaic Period, reduces, but does not eliminate, these inherent problems. Dee & et al., uses this approach, and derive a 65% confidence interval estimate for the beginning of the First Dynasty of c. 3211 – 3045 BC. However, they define the beginning of the First Dynasty as the beginning of the reign of Hor-Aha. There are no radiocarbon dates for Narmer, so to translate this to the beginning of Narmer's reign one must again adjust for the length of Narmer's reign of 62 years, which gives a range of c. 3273–3107 BC for the beginning of Narmer's reign. This is reassuringly close to the range of mainstream Egyptologists using the Historical Method of c. 3114 – 2987 BC. Thus, combining the results of two different methodologies allows to place the accession of Narmer to c. 3273 – 2987 BC.

- ^ According to Schulman the Narmer Palette commemorates a conquest of Libyans that occurred earlier than Narmer, probably during Dynasty 0. Libyans, in this context, were not people who inhabited what is modern Libya, but rather peoples who lived in the north-west Delta of the Nile, which later became a part of Lower Egypt. Schulman describes scenes from Dynasty V (2 scenes), Dynasty VI, and Dynasty XXV. In each of these, the king is shown defeating the Libyans, personally killing their chief in a classic "smiting the enemy" pose. In three of these post-Narmer examples, the name of the wife and two sons of the chief are named—and they are the same names for all three scenes from vastly different periods. This proves that all, but the first representation, cannot be recording actual events, but are ritual commemorations of an earlier event. The same might also be true of the first example in Dynasty V. The scene on the Narmer Palette is similar, although it does not name the wife or sons of the Libyan chief. The Narmer Palette could represent the actual event on which the others are based. However, Schulman (following Breasted 1931) argues against this on the basis that the Palermo Stone shows predynastic kings wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt suggesting that they ruled a unified Egypt. Hence, the Narmer Palette, rather than showing a historic event during Narmer's reign commemorates the defeat of the Libyans and the unification of Egypt which occurred earlier. Köhler 2002, p. 505 proposes that the Narmer Palette has nothing to do with the unification of Egypt. Instead, she describes it as an example of the "subjecting the enemy" motif which goes back as far as Naqada Ic (about 400 years before Narmer), and which represents the ritual defeat of chaos, a fundamental role of the king. O'Connor 2011 also argues that it has nothing to do with the unification, but has a (very complicated) religious meaning.

- ^ During the summer of 1994, excavators from the Nahal Tillah expedition, in southern Israel, discovered an incised ceramic sherd with the serekh sign of Narmer. The sherd was found on a large circular platform, possibly the foundations of a storage silo on the Halif Terrace. Dated to c. 3000 BCE, mineralogical studies conducted on the sherd conclude that it is a fragment of a wine jar which had been imported from the Nile valley to Canaan.[61]

- ^ In 2012, Pierre Tallet discovered an important new series of rock carvings in Wadi Ameyra. This discovery was reported in Tallet 2015, and in 2016 in two web articles by Owen Jarus[71] These inscriptions strongly suggest that Neithhotep was Djer's regent for a period of time, but do not resolve the question of whether she was Narmer's queen. In the first of Jarus' articles, he quotes Tallet as saying that Neithhotep "was not the wife of Narmer". However, Tallet, in a personal communication with Thomas C. Heagy explained that he had been misquoted. According to Tallet, she could have been Narmer's wife (Djer's grandmother), but that it is more likely (because Narmer and Hor-Aha are both thought to have had long reigns) that she was in the next generation—for example Djer's mother or aunt. This is consistent with the discussion in Tallet 2015, pp. 28–29.

- ^ For a discussion of Cemetery B see Dreyer 1999, pp. 110–11, fig. 7 and Wilkinson 2000, pp. 29–32, fig. 2

- ^ Narmer's tomb has much more in common with the tombs of his immediate predecessors, Ka and Iry-Hor, and other late Predynastic tombs in Umm el-Qa'ab than it does with later 1st Dynasty tombs. Narmer's tomb is 31 sq. meters compared to Hor-Aha, whose tomb is more than three times as large, not counting Hor-Aha's 36 subsidiary graves. According to Deyer,[74] Narmer's tomb is even smaller than the tomb of Scorpion I (tomb Uj), several generations earlier.[75] In addition, the earlier tombs of Narmer, Ka, and Iry-Hor all have two chambers with no subsidiary chambers, while later tombs in the 1st Dynasty all have more complex structures including subsidiary chambers for the tombs of retainers, who were probably sacrificed to accompany the king in the afterlife.O'Connor 2009, pp. 148–150 To avoid confusion, it's important to understand that he classifies Narmer as the last king of the 0 Dynasty rather than the first king of the 1st Dynasty, in part because Narmer's tomb has more in common with the earlier 0 Dynasty tombs than it does with the later 1st Dynasty tombs.Dreyer 2003, p. 64 also makes the argument that the major shift in tomb construction that began with Hor-Aha, is evidence that Hor-Aha, rather than Narmer was the first king of the 1st Dynasty.

- ^ Numerous publications with either Werner Kaiser or his successor, Günter Dreyer, as the lead author—most of them published in MDAIK beginning in 1977

- ^ Next to Hor-Aha's enclosure is a large, unattributed enclosure referred to as the "Donkey Enclosure" because of the presence of 10 donkeys buried next to the enclosure. No objects were found in the enclosure with a king's name, but hundreds of seal impressions were found in the gateway chamber of the enclosure, all of which appear to date to the reigns of Narmer, Hor-Aha, or Djer. Hor-Aha and Djer both have enclosures identified, "making Narmer the most attractive candidate for the builder of this monument".[82] The main objection to its assignment to Narmer is that the enclosure is too big. It is larger than all three of Hor-Aha's put together, while Hor-Aha's tomb is much larger than Narmer's tomb. For all of the clearly identified 1st Dynasty enclosures, there is a rough correlation between the size of the tomb and the size of the enclosure. Identifying the Donkey Enclosure with Narmer would violate that correlation. That leaves Hor-Aha and Djer. The objection to the assignment of the enclosure to Aha is the inconsistency of the subsidiary graves of Hor-Aha's enclosure, and subsidiary graves of the donkeys. In addition, the seeming completeness of the Aha enclosure without the Donkey Enclosure, argues against Hor-Aha. This leaves Djer, whom Bestock considers the most likely candidate. The problems with this conclusion, as identified by Bestock, are that the Donkey Enclosure has donkeys in the subsidiary graves, whereas Djer has humans in his. In addition, there are no large subsidiary graves at Djer's tomb complex that would correspond to the Donkey Enclosure.[83] She concludes that, "the interpretation and attribution of the Donkey Enclosure remain speculative."[84] There are, however, two additional arguments for the attribution to Narmer: First, it is exactly where one would expect to find Narmer's Funerary Enclosure—immediately next to Hor-Aha's. Second, all of the 1st Dynasty tombs have subsidiary graves for humans except that of Narmer, and all of the attributed 1st Dynasty enclosures, except the Donkey Enclosure, have subsidiary graves for humans. But neither Narmer's tomb nor the Donkey Enclosure have known subsidiary graves for humans. The lack of human subsidiary graves at both sites seems important. It is also possible that Narmer had a large funerary enclosure precisely because he had a small tomb.[85][86] In the absence of finding an object with a Narmer's name on it, any conclusion must be tentative, but it seems that the preponderance of evidence and logic support the identification of the Donkey Enclosure with Narmer.

- ^ Of these inscriptions, 29 are controversial or uncertain. They include the unique examples from Coptos, En Besor, Tell el-Farkhan, Gebel Tjauti, and Kharga Oasis, as well as both inscriptions each from Buto and Tel Ma'ahaz. Sites with more than one inscription are footnoted with either references to the most representative inscriptions, or to sources that are the most important for that site. All of the inscriptions are included in the Narmer Catalog, which also includes extensive bibliographies for each inscription. Several references discuss substantial numbers of inscriptions. They include: Database of Early Dynastic Inscriptions, Kaplony 1963, Kaplony 1964, Kaiser & Dreyer 1982, Kahl 1994,van den Brink 1996, van den Brink 2001, Jiménez-Serrano 2003, Jiménez-Serrano 2007, and Pätznick 2009. Anđelković 1995 includes Narmer inscriptions from Canaan within the context of the overall relations between Canaan and Early Egypt, including descriptions of the sites in which they were found.

References

- ^ a b Pätznick 2009, pp. 308, n.8.

- ^ a b Leprohon 2013, p. 22.

- ^ a b Clayton 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Stewart, John (2006). African States and Rulers (Third ed.). London: McFarland. p. 81. ISBN 0-7864-2562-8.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 67.

- ^ a b Heagy 2014, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Cervelló-Autuori 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Grimal 1994.

- ^ Edwards 1971, p. 13.

- ^ Garstang 1905, p. 62, fig3

- ^ "Naqada Label | the Ancient Egypt Site".

- ^ Borchardt 1897, pp. 1056–1057.

- ^ Newberry 1929, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Kinnear 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Newberry 1929, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Helck 1953, pp. 356–359.

- ^ Heagy 2014, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Dreyer 1987, p. 36, fig.3

- ^ Dreyer 1987.

- ^ Dreyer et al. 1996, pp. 72–73, fig. 6, pl.4b-c.

- ^ Cervelló-Autuori 2008, pp. 887–899.

- ^ Wengrow 2006, p. 207.

- ^ Brewer & Friedman 1989, p. 63.

- ^ Redford 1986, pp. 136, n.10.

- ^ Pätznick 2009, p. 287.

- ^ Ray 2003, pp. 131–138.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 23–32.

- ^ Raffaele 2003, pp. 110, n. 46.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Regulski 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Godron 1949, p. 218.

- ^ Pätznick 2009, p. 310.

- ^ a b c G. Dreyer, personal communication to Thomas C Heagy, 2017

- ^ Hayes 1970, p. 174.

- ^ Quirke & Spencer 1992, p. 223.

- ^ Quibell 1898, pp. 81–84, pl. XII-XIII.

- ^ Gardiner 1961, pp. 403–404.

- ^ a b Dreyer 2000.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Davies & Friedman 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Baines 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Wengrow 2006, p. 204.

- ^ Millet 1990, pp. 53–59.

- ^ Wengrow 2006, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Dreyer, Hartung & Pumpenmeier 1993, p. 56, fig. 12.

- ^ Kahl 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Dreyer 2011, p. 135.

- ^ a b Jiménez-Serrano 2007, p. 370, table 8.

- ^ Ciałowicz 2011, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Heagy 2014, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Quibell 1900, p. 7, pl. XV.7.

- ^ Dreyer 2016.

- ^ Quibell 1900, pp. 8–9, pls. XXV, XXVIB.

- ^ Anđelković 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Braun 2011, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Anđelković 2011, p. 31.

- ^ Anđelković 2011, p. 31.

- ^ Jiménez-Serrano 2007, p. 370, Table 8.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 71.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 71–105.

- ^ Levy et al. 1995, pp. 26–35.

- ^ a b Porat 1986–87, p. 109.

- ^ Yadin 1955.

- ^ Campagno 2008, pp. 695–696.

- ^ de Miroschedji 2008, pp. 2028–2029.

- ^ a b Dreyer 2016, p. 104.

- ^ a b Tyldesley 2006, pp. 26–29.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 70.

- ^ Emery 1961, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Tallet 2015.

- ^ Owen Jarus: Early Egyptian Queen revealed in 5.000-year-old Hieroglyphs at livescience.com

- ^ Heagy 2020.

- ^ Kaiser 1964, pp. 96–102, fig.2.

- ^ Kaiser et al.

- ^ Dreyer 1988, p. 19.

- ^ a b Petrie 1900.

- ^ a b Petrie 1901.

- ^ Petrie 1901, p. 22.

- ^ a b Petrie 1901, pp. pl.VI..

- ^ Adams & O'Connor 2003, pp. 78–85.

- ^ O'Connor 2009, pp. 159–181.

- ^ Bestock 2009, p. 102.

- ^ Bestock 2009, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Bestock 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Dreyer 1998, p. 19.

- ^ Bestock 2009, p. 103, n.1.

- ^ Quibell 1898, pp. 81–84, pl. XII–XIII.

- ^ Spencer 1980, p. 64(454), pl. 47.454, pl.64.454.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0084 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Williams 1988, pp. 35–50, fig. 3a.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0085

- ^ Petrie, Wainwright & Gardiner 1913.

- ^ Petrie 1914.

- ^ Saad 1947, pp. 26–27.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0114 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunham 1978, pp. 25–26, pl. 16A.

- ^ van den Brink 1992, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Bakr 1988, pp. 50–51, pl. 1b.

- ^ Wildung 1981, pp. 35–37.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0121 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lacau & Lauer 1959, pp. 1–2, pl. 1.1.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0115 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ von der Way 1989, pp. 285–286, n.76, fig. 11.7.

- ^ Jucha 2008, pp. 132–133, fig. 47.2.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/6002

- ^ Hassan 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Winkler 1938, pp. 10, 25, pl.11.1.

- ^ Ikram & Rossi 2004, pp. 211–215, fig. 1-2.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/6015 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Darnell & Darnell 1997, pp. 71–72, fig. 10.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/4037 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Amiran 1974, pp. 4–12, fig. 20, pl.1.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0123

- ^ Schulman 1976, pp. 25–26.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0547 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ de Miroschedji & Sadeq 2000, pp. 136–137, fig. 9.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/6009 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Levy et al. 1997, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Yeivin 1960, pp. 193–203, fig. 2, pl. 24a.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/0124 Archived 2020-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Amiran, Ilan & Aron 1983, pp. 75–83, fig.7c.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/6006 Archived 2017-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schulman & Gophna 1981.

- ^ van den Brink & Braun 2002, pp. 167–192.

- ^ Tallet & Laisney 2012, pp. 383–389.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/4814 Archived 2020-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gatto et al. 2009.

- ^ a b Darnell 2015.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog http://narmer.org/inscription/6014

- ^ Gatto 2012.

- ^ Picker 2012.

- ^ Collins 2013.

- ^ French 2007.

- ^ "Warframe: Updates". Warframe. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

Bibliography

- Adams, Matthew; O'Connor, David (2003), "The Royal mortuary enclosures of Abydos and Hierakonpolis", in Hawass, Zahi (ed.), The treasures of the pyramids, Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, pp. 78–85.

- Amiran, Ruth (1974), "An Egyptian jar fragment with the name of Narmer from Arad", IEJ, 24, 1: 4–12

- Amiran, R.; Ilan, O.; Aron, C. (1983), "Excavations at Small Tel Malhata: Three Narmer serekhs", IEJ, 2: 75–83.

- Anđelković, B (1995), The Relations Between Early Bronze Age I Canaanites and Upper Egyptians, Belgrade: Faculty of Philosophy, Center for archaeological Research, ISBN 978-86-80269-17-7.

- ——— (2011), "Political Organization of Egypt in the Predynastic Period", in Teeter, E (ed.), Before the Pyramids, Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- Baines, J (1995), "Origins of Egyptian Kingship", in O'Connor, D; Silverman, DP (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Kingship, Leiden, New York, Cologne: EJ Brill, pp. 95–156, ISBN 978-90-04-10041-1.

- Baines, John (2008), "On the evolution, purpose, and forms of Egyptian annals", in Engel, Eva-Maria; Müller, Vera; Hartung, Ulrich (eds.), Zeichen aus dem Sand: Streiflichter aus Ägyptens Geschichte zu Ehren von Günter Dreyer, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 19–40.

- Bakr, M.I. (1988), "The new excavations at Ezbet el-Tell, Kufur Nigm; the first season (1984)", in van den Brink, E.C.M. (ed.), The archaeology of the Nile Delta: Problems and priorities. Proceedings of the seminar held in Cairo, 19–22 October 1986, on the occasion of the fifteenth anniversary of the Netherlands Institute of Archaeology and Arabic Studies in Cairo, Amsterdam, pp. 49–62

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Bestock, Laurel (2009), The development of royal funerary cult at Abydos: two funerary enclosures from the reign of Aha, Menes, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz

- Braun, E (2011), "Early Interaction Between Peoples of the Nile Valley and the Southern Levant", in Teeter, E (ed.), Before the Pyramids, Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- Breasted, James H. (1931), "The predynastic union of Egypt", Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, 30: 709–724, doi:10.3406/bifao.1931.1923.

- Brewer, D.J.; Friedman, R.F. (1989), Fish and fishing in ancient Egypt, Cairo: The American University Press in Cairo.

- Campagno, M (2008), "Ethnicity and Changing Relationships between Egyptians and South Levantines during the Early Dynastic Period", in Midant-Reynes; Tristant, Y (eds.), Egypt at its Origins, vol. 2, Leuven: Peeters, ISBN 978-90-429-1994-5.

- Cervelló-Autuori, Josep (2003), "Narmer, Menes and the seals from Abydos", Egyptology at the dawn of the twenty-first century: proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, 2000, vol. 2, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 9789774247149.

- Cervelló-Autuori, Josep (2005), "Was King Narmer Menes?", Archéo-Nil, 15: 31–46, doi:10.3406/ARNIL.2005.896.

- Cervelló-Autuori, J. (2008), "The Thinite "Royal Lists": Typology and meaning", in Midant-Reynes, B.; Tristant, Y.; Rowland, J.; Hendrickx, S. (eds.), Egypt at its origins 2. Proceedings of the international conference "Origin of the state. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt", Toulouse (France), 5th – 8th September 2005, OLA, Leuven

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Charron, Alain (1990), "L'époque thinite", L'Égypte des millénaires obscures, Paris, pp. 77–97

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Ciałowicz, KM (2011), "The Predynastic/Early Dynastic Period at Tell el-Farkha", in Teeter, E (ed.), Before the Pyramids, Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 55–64, ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames and Hudson..

- Collins, William G. (2013), Murder by the Gods: An Ancient Egyptian Mystery, CreateSpacePublishing.

- Darnell, John Coleman; Darnell, Deborah (1997). "Theban Desert Road Survey" (PDF). The Oriental Institute Annual Report, 1996–1997. Chicago: 66–76.

- Darnell, John Coleman (2015), "The Early Hieroglyphic Annotation in the Nag el-Hamdulab Rock Art Tableaux, and the Following of Horus in the Northwest Hinterland of Aswan", Archeo-Nil, 25: 19–43, doi:10.3406/ARNIL.2015.1087

- Davies, Vivian; Friedman, Renée (1998), Egypt Uncovered, New York: Stewart, Taboti & Chang.

- Dee, Michael; Wengrow, David; Shortland, Andrew; Stevenson, Alice; Brock, Fiona; Flink, Linus Girland; Ramsey, Bronk. "An absolute chronology for early Egypt using radiocarbon dating and Bayesian statistical modeling". Proceedings of the Royal society. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

published 2013

. - Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004), The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Dreyer, G. (1987), "Ein Siegel der frühzeitlichen Königsnekropole von Abydos", MDAIK, 43: 33–44.

- Dreyer, G (1999), "Abydos, Umm el-Qa'ab", in Bard, KA; Shubert, SB (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-18589-9.

- ——— (2000), "Egypt's Earliest Event", Egyptian Archaeology, 16.

- Dreyer, G. (2007), "Wer war Menes?", in Hawass, Z.A.; Richards, J. (eds.), The archaeology and art of Ancient Egypt. Essays in honor of David B. O'Connor, CASAE, vol. 34, Cairo

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Dreyer, Günter (2011), "Tomb U-J: a royal burial of Dynasty 0 at Abydos", in Teeter, Emily (ed.), Before the pyramids: the origins of Egyptian civilization, Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 127–136.

- Dreyer, Günter (2016), "Dekorierte Kisten aus dem Grab des Narmer", Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo, vol. 70–71 (2014–2015), pp. 91–104

- Dreyer, Günter; Hartung, Ulrich; Pumpenmeier, Frauke (1993), "Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof, 5./6. Vorbericht", Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo, 49: 23–62.

- Dreyer, G.; Engel, E.M.; Hartung, U.; Hikade, T.; Köler, E.C.; Pumpenmeier, F. (1996), "Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof, 7./8. Vorbericht", MDAIK, 52: 13–81.

- Dunham, D. (1978), Zawiyet el-Aryan: The cemeteries adjacent to the Layer Pyramid, Boston

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Edwards, I.E.S (1971), "The early dynastic period in Egypt", The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Emery, W.B. (1961). Archaic Egypt: Culture and Civilization in Egypt Five Thousand Years Ago. London: Penguin Books..

- French, Jackie (2007), Pharaoh: The Boy Who Conquered the Nile, HarperCollins.

- Gardiner, Alan (1961), Egypt of the Pharaohs, Oxford University Press.

- Godron, G. (1949), "A propos du nom royal [hieroglyphs]", Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte, 49: 217–220, 547.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, Massachusetts; Oxford, United Kingdom; Carlton, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-6311-9396-8.

- Hassan, FA (2000), "Kafr Hassan Dawood", Egyptian Archaeology, 16: 37–39.

- Hayes, Michael (1970), "Chapter VI.Chronology, I. Egypt to the end of the Twentieth Dynasty", in Edwards, I.E.S.; Gadd, C.J. (eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume I, Part I, Cambridge

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Heagy, Thomas C. (2020), "Narmer", in Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R (eds.), Encyclopedia of Ancient History, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, doi:10.1002/9781444338386, hdl:1808/11108, ISBN 9781405179355.

- Heagy, Thomas C. (2014), "Who was Menes?", Archeo-Nil, 24: 59–92, doi:10.3406/ARNIL.2014.1071.

- Heagy, Thomas C. "The Narmer Catalog".

- Helck, W. (1953), "Gab es einen König Menes?", Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 103, n.s. 28: 354–359.

- Helck, W. (1986), Geschichte des alten Ägypten, Handbuch des Orientalistik 1/3, Leiden; Köln

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Hendrickx, Stan (2006), "II.1 Predynastic-Early Dynastic Chronology", in Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Walburton, David A. (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Chronology, Leiden

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Hendrickx, Stan (2017), Narmer Palette Bibliography (PDF).

- Hendrickx, Stan; De Meyer, Marleen; Eyckerman, Merel (2014), "On the origin of the royal false beard and its bovine symbolism", in Jucha, Mariusz A; Dębowska-Ludwin, Joanna; Kołodziejczyk, Piotr (eds.), Aegyptus est imago caeli: studies presented to Krzysztof M. Ciałowicz on his 60th birthday, Kraków: Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Kraków; Archaeologica Foundation, pp. 129–143.

- Ikram, S.; Rossi, C. (2004), "A new Early Dynastic serekh from the Kharga Oasis", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 90: 211–215, doi:10.1177/030751330409000112, S2CID 190218264

- Jiménez-Serrano, A. (2003), "Chronology and local traditions: The representation of power and the royal name in the Late Predynastic Period", Archéo-Nil, 13: 93–142, doi:10.3406/ARNIL.2003.1141.

- Jiménez-Serrano (2007), Los Primeros Reyes y la Unificación de Egipto [The first kings and the unification of Egypt] (in Spanish), Jaen, ES: Universidad de Jaen, ISBN 978-84-8439-357-3.

- Jucha, M.A. (2008), Chłondicki, M.; Ciałowicz, K.M. (eds.), "Pottery from the grave [in] Polish Excavations at Tell el-Farkha (Ghazala) in the Nile Delta. Preliminary report 2006–2007", Archeologia, 59: 132–135.

- Kahl, J. (1994), Das System der ägyptischen Hieroglypheninschrift in der 0.-3. Dynastie, Göttinger Orientforschungen. 4. Reihe: Ägypten, vol. 29, Wiesbaden

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) . - Kahl, Jochem (2007), "Ober- und Unterägypten: eine dualistische Konstruktion und ihre Anfänge", in Albertz, Rainer; Blöbaum, Anke; Funke, Peter (eds.), Räume und Grenzen: topologische Konzepte in den antiken Kulturen des östlichen Mittelmeerraums, München: Herbert Utz, pp. 3–28

- Kaiser, W.; Dreyer, G. (1982), "Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof, 2. Vorbericht", MDAIK, 38: 211–270.

- Kaplony, P. (1963), Die Inschriften der ägyptischen Frühzeit, Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, vol. 8, Wiesbaden

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Kaplony, P. (1964), Die Inschriften der ägyptischen Frühzeit: Supplement, Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, vol. 9, Wiesbaden

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Kinnaer, J. (2001), "Aha or Narmer. Which was Menes?", KMT, 12, 3: 74–81.

- Kinnaer, Jacques (2003), "The Naqada label and the identification of Menes", Göttinger Miszellen, 196: 23–30.

- Kinnaer, Jacques (2004), "What is Really Known About the Narmer Palette?", KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2000), "3.1 Regional and Genealogical Data of Ancient Egypt (Absolute Chronology I) The Historical Chronology of Ancient Egypt, A Current Assessment", in Bietak, Manfred (ed.), The Synchronization of Civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium, Wein

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Köhler, E. Christiana (2002), "History or ideology? New reflections on the Narmer palette and the nature of foreign relations in Pre- and Early Dynastic Egypt", in van den Brink, Edwin C. M.; Levy, Thomas E. (eds.), Egypt and the Levant: interrelations from the 4th through the early 3rd millennium BCE, London; New York: Leicester University Press, pp. 499–513.

- Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David Alan (2006), "Conclusions", in Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf K.; Warburton, David A. (eds.), Ancient Egypt Chronology, Handbuch der Orientalistik. Section 1: The Near and Middle East: – 1:83, Leiden; Boston

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Lacau, J.P.; Lauer, P. (1959), La Pyramide à degrés. vol. 4. Inscriptions gravées sur les vases, Excavations at Saqqara/Fouilles à Saqqarah, vol. 8, Cairo

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Leprohon, Ronald Jacques (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Writings from the Ancient World. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature..

- Lloyd, Alan B (1994) [1975], Herodotus: Book II, Leiden: EJ Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-04179-0.

- Levy, TE; van den Brink, ECM; Goren, Y; Alon, D (1995), "New Light on King Narmer and the Protodynastic Egyptian Presence in Canaan", The Biblical Archaeologist, 58 (1): 26–35, doi:10.2307/3210465, JSTOR 3210465, S2CID 193496493.

- Levy, T.E.; van den Brink, E.C.M.; Goren, Y.; Alon, D. (1997), "Egyptian-Canaanite interaction at Nahal Tillah, Israel (ca. 4500–3000 B.C.E.): An interim report on the 1994–1995 excavations", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 307 (307): 1–51, doi:10.2307/1357702, JSTOR 1357702, S2CID 161748881.

- Manetho (1940), Manetho, translated by Wadell, W.G., Cambridge

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mellaart, James (1979), "Egyptian and Near Eastern chronology: a dilemma?", Antiquity, 53 (207): 6–18, doi:10.1017/S0003598X00041958, S2CID 162414996

- Midant-Reynes, B (2000), The Prehistory of Egypt.

- Millet, N. B. (1990), "The Narmer Macehead and Related Objects", JARCE, 27: 53–59, doi:10.2307/40000073, JSTOR 40000073

- de Miroschedji, P.; Sadeq, M. (2000), "Tell es-Sakan, un site du Bronze ancien découvert dans la région de Gaza", Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 144 (1): 123–144, doi:10.3406/CRAI.2000.16103.

- de Miroschedji, P; Sadeq, M (2008), "Sakan, Tell Es-", in Stern, E; Geva, H; Paris, A (eds.), The new Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Supplementary Volume, vol. 5.

- Newberry, Percy E. (1929), "Menes: the founder of the Egyptian monarchy (circa 3400 B.C.)", in Anonymous (ed.), Great ones of ancient Egypt: portraits by Winifred Brunton, historical studies by various Egyptologists, London: Hodder and Stoughton, pp. 37–53.

- O'Connor, David (2009), Abydos: Egypt's first pharaohs and the cult of Osiris. New aspects of antiquity, London: Thames & Hudson.

- O'Connor, David (2011), "The Narmer Palette: A New Interpretation", in Teeter, E (ed.), Before the Pyramids, Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- Pätznick, Jean-Pierre (2009), "Encore et toujours l'Horus Nâr-mer? Vers une nouvelle approche de la lecture et de l'interprétation de ce nom d'Horus", in Régen, Isabelle; Servajean, Frédéric (eds.), Verba manent: recueil d'études dédiées à Dimitri Meeks par ses collègues et amis 2, Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry, pp. 307–324.

- "Petrie Museum of Egyptian Art (University College London)"..

- Petrie, W.M.F. (1900), Royal tombs of the First Dynasty. Part 1, Memoir, vol. 18, London: EEF.

- Petrie, W.M.F. (1901), Royal tombs of the First Dynasty. Part 2, Memoir, vol. 21, London: EEF.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders (1939), The making of Egypt, British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account, vol. 61, London: Sheldon Press.

- Petrie, W.M.F.; Wainwright, G.; Gardiner, A.H. (1913), Tarkhan I and Memphis V, London: BSAE.

- Petrie, W.M.F. (1914), Tarkan II, London: BSAE.

- Picker, Lester (2012), The First Pharaoh (The First Dynasty Book 1), Aryeh Publishing.

- Porat, N (1986–87), "Local Industry of Egyptian Pottery in Southern Palestine during the Early Bronze Period", Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar, 8.

- Quibell, JE (1898). "Slate Palette from Hierakonpolis". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 36: 81–84, pl. XII–XIII. doi:10.1524/zaes.1898.36.jg.81. S2CID 192825246..

- Quibell, J. E. (1900), Hierakonpolis, Part I, British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account, vol. 4, London: Bernard Quaritch.

- Quirke, Stephen; Spencer, Jeffery (1992), The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Regulski, Ilona (2010). A paleographic study of early writing in Egypt. Orientalia Lovaniensia. Leuven-Paris-Walpole, MA: Uitgeverij Peeters and Departement Oosterse Studies.

- Redford, Donald B. (1986). Pharaonic King-Lists, Annals, and Day-Books: a Contribution to the Study of the Egyptian Sense of History. Mississauga, Ontario: Benben Publications. ISBN 0-920168-08-6..

- Regulksi, I. "Database of Early Dynastic Inscriptions". Archived from the original on 2017-09-02. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- Saad, Z.Y. (1947), Royal excavations at Saqqara and Helwan (1941–1945), Supplément aux annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte, vol. 3, Cairo

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Schulman, AR (1991–92), "Narmer and the Unification: A Revisionist View", Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar, 11: 79–105.

- Schulman, A.R. (1976), "The Egyptian seal impressions from 'En Besor", 'Atiqot, 11: 16–26.

- Schulman, A.R.; Gophna, R. (1981), "An Egyptian serekh from Tel Ma'ahaz", IEJ, 31: 165–167.

- Seidlmayer, S (2010), "The Rise of the Egyptian State to the Second Dynasty", in Schulz, R; Seidel, M (eds.), Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs.

- Shaw, Ian (2000a), "Introduction: Chronologies and Cultural Change in Egypt", in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford, pp. 1–16

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Shaw, Ian (2000b), "Chronology", in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford, pp. 479–483

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Spencer, A.J. (1980), Catalog of Egyptian Antiquities in the British Museum. vol.V. Early Dynastic objects, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Stevenson, Alice (2015), The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections, UCL Press, p. 44

- Tallet, Pierre (2015), La zone minière pharaonique du Sud-Sinaï – II: Les inscriptions pré- et protodynastiques du Ouadi 'Ameyra (CCIS nos 273–335), Mémoires publiés par les membres de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. 132, Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Tallet, P.; Laisney, D (2012), "Iry-Hor et Narmer au Sud-Sinaï: Un complément à la chronology des expéditions minères égyptiennes", Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, 112: 381-298[page needed].

- Tassie, G.J.; Hassan, F.A.; Van Wettering, J.; Calcoen, B. (2008), "Corpus of potmarks from the Protodynastic to Early Dynastic cemetery at Kafr Hassan Dawood, Wadi Tumilat, East Delta, Egypt", in Midant-Reynes, B.; Tristant, Y. (eds.), Egypt at its origins 2. Proceedings of the International Conference "Origin of the state. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt", Toulouse (France), 5th – 8th September 2005, OLA, vol. 172, Leuven, pp. 203–235

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Trope, Betsy Teasley; Quirke, Stephen; Lacovara, Peter (2005), Excavating Egypt: great discoveries from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College, London, Atlanta: Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2006), Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson.

- von Beckerath, Jurgen (1997), Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, Müncher Ägyptologische Studien: – 46, Mainz

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - van den Brink, E.C.M. (1992), "Preliminary Report on the Excavations at Tell Ibrahim Awad, Seasons 1988–1990", in van den Brink, E.C.M. (ed.), The Nile Delta in transition: 4th–3rd Millennium B.C., Proceedings of the seminar held in Cairo, 21–24 October 1990, Tel Aviv, pp. 43–68

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - van den Brink, Edwin C. M.; Braun, Eliot (2002), "Wine jars with serekhs from Early Bronze Lod: Appelation vallée du nil contrôlée, but for whom?", in van den Brink, E.C. M.; Yannai, E. (eds.), In quest of ancient settlements and landscapes: Archaeological studies in honour of Ram Gophna, Tel Aviv, pp. 167–192

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - van den Brink, E.C.M. (1996), "The incised serekh-signs of dynasties 0–1, Part I: Complete vessels", in Spencer, A.J. (ed.), Aspects of early Egypt, London, pp. 140–158

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - van den Brink, E.C.M. (2001), "The pottery-incised serekh-signs of Dynasties 0–1. Part II: Fragments and additional complete vessels", Archéo-Nil, 11: 24–100, doi:10.3406/ARNIL.2001.1239.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien. Münchener Universitätsschriften, Philosophische Faklutät. Vol. 49. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- von der Way, T. (1989), "Tell el-Fara'in – Buto", MDAIK, 45: 275–308.

- Wengrow, David (2006), The archaeology of early Egypt: social transformations in North-East Africa, 10,000 to 2650 BC, Cambridge world archaeology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521835862.

- Wildung, D. (1981), Ägypten vor den Pyramiden: Münchener Ausgrabungen in Ägypten, Mainz am Rhein

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Wilkinson, TAH (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London; New York: Routledge.

- Wilkinson, T. A. H. (2000), "Narmer and the concept of the ruler", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 86: 23–32, doi:10.2307/3822303, JSTOR 3822303.

- Williams, B. (1988), "Narmer and the Coptos Colossi", Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 25: 35–59, doi:10.2307/40000869, JSTOR 40000869.

- Winkler, H.A. (1938), Rock drawings of southern Upper Egypt I. Sir Robert Mond Desert Expedition Season 1936–1937, Preliminary Report, EES, vol. 26, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Yadin, Y (1955), "The Earliest record of Egypt Military Penetration into Asia?", Israel Exploration Journal, 5 (1).

- Yeivin, S. (1960), "Early contacts between Canaan and Egypt", Israel Exploration Journal, 10, 4: 193–203.

Further reading

- Davis, Whitney. 1992. Masking the Blow: The Scene of Representation In Late Prehistoric Egyptian Art. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Goldwasser, Orly. 1992. "The Narmer Palette and the 'Triumph of Metaphor'." Lingua Aegyptia 2: 67–85.

- Muhlestein, Kerry. 2011. Violence In the Service of Order: The Religious Framework for Sanctioned Killing In Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Ray, John D. 2003. "The Name of King Narmer." Lingua Aegyptia 11: 131–38.

- Shaw, Ian. 2004. Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Takacs, Gabor. 1997. "Note on the Name of King Narmer." Linguistica 37, no. 1: 53–58.

- Wengrow, David. 2001. "Rethinking 'Cattle Cults' in Early Egypt: Towards a Prehistoric Perspective on the Narmer Palette." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 11, no. 1: 91–104.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. 2000. "What a King Is This: Narmer and the Concept of the Ruler." Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 86: 24–32.

- Williams, Bruce, Thomas J. Logan, and William J. Murnane. 1987. "The Metropolitan Museum Knife Handle and Aspects of Pharaonic Imagery before Narmer." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 46, no. 4: 245–85.

![Arrowheads from Narmer's tomb, Petrie 1905, Royal Tombs II, pl. IV.14. According to Dreyer,[33] these arrowheads are probably from the tomb of Djer, where similar arrowheads were found.[79]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/b/b0/Flint_arroheads_from_Narmer%27s_tomb.jpg/170px-Flint_arroheads_from_Narmer%27s_tomb.jpg)