Cybersecurity and privacy risk assessment of point-of-care systems in healthcare: A use case approach

Contents

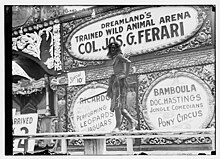

Seen in 1907 | |

| Location | Coney Island, New York, US |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°34′28″N 73°58′37″W / 40.57444°N 73.97694°W |

| Status | Defunct |

| Opened | May 15, 1904 |

| Closed | May 27, 1911 |

| Owner | William H. Reynolds |

Dreamland was an amusement park that operated in the Coney Island neighborhood of Brooklyn in New York City, United States, from 1904 to 1911. It was the last of the three original large parks built on Coney Island, along with Steeplechase Park and Luna Park.[1] The park was between Surf Avenue to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It was arranged roughly as a horseshoe, with a pier facing south toward the Atlantic Ocean. Dreamland contained several attractions that were larger versions of those at Luna Park, and it included a human zoo, several early roller coasters, a Shoot the Chutes ride, and a replica of Venice. Dreamland also hosted entertainment and dramatic spectacles based on morality themes. Several structures, such as the Pompeiian, Electricity, and Submarine Boat buildings, were dedicated to exhibits.

Former state senator William H. Reynolds announced plans in July 1903 for an amusement park rivaling Luna Park, originally known as the Hippodrome. The Dreamland Company started constructing the park in December 1903, and the park opened as Dreamland on May 15, 1904. The park operated between May and September of each year, and Reynolds constantly changed Dreamland's shows and attractions every season. Coney Island had reached its peak popularity by the late 1900s, but Dreamland struggled to compete with Luna Park, which was better managed.

During the early morning of May 27, 1911, just after the start of Dreamland's eighth season, a worker kicked over a bucket of hot pitch, starting a fire that spread through the park's wooden buildings. Firefighters were unable to control the fire because of low water pressure; nearly all of the structures were quickly destroyed, although no one was killed. The site's northern portion, on Surf Avenue, was quickly redeveloped with various concessions. The New York City government acquired the southern portion through condemnation in 1912, but disputes over compensation continued for eight years. The site became a parking lot in 1921 and was redeveloped as a recreation center in 1935; the New York Aquarium was eventually built on the site in 1957.

Development

Between about 1880 and World War II, Coney Island was the largest amusement area in the United States, attracting several million visitors per year.[2] Sea Lion Park opened in 1895 and was Coney Island's first amusement area to charge entry fees;[3][4] this in turn spurred the construction of George C. Tilyou's Steeplechase Park in 1897, the neighborhood's first major amusement park.[3][5] Frederic Thompson and Elmer "Skip" Dundy opened Luna Park, Coney Island's second major amusement park, in 1903 on the site of Sea Lion Park, which had closed the previous year.[6][7] William H. Reynolds, a former state senator and successful Brooklyn real estate developer, decided to construct Dreamland following the success of Luna Park.[8][9][10] He intended for Dreamland to compete with Luna Park. Dreamland was supposed to be refined and elegant in its design and architecture, compared to Luna Park with its many rides and chaotic noise.[11]

Reynolds announced plans in July 1903 for an amusement park rivaling Luna Park, which was to be built in a style resembling London's Hippodrome.[12][13] According to local media, he reportedly paid $180,000 for a pier on the Coney Island Beach,[14] as well as $447,500 for two parcels at Surf Avenue and West Eighth Street,[a] measuring 800 feet (240 m) deep and 262 feet (80 m) wide.[13][14] The Times Union subsequently said that the purchase prices for the site were not correct.[16] The Surf Avenue parcels had belonged to John Y. McKane,[13] who had operated a bathing house on the site.[17][18] Previously, the parcels had also included the Coney Island Athletic Club's arena[16] and the Culver Depot, the then-terminal of what is now the New York City Subway's Brighton and Culver lines.[16] Although C. L. Turnbull and P. I. Thompson were nominally the buyers, but they acted as proxies for Reynolds, allowing him to acquire the Surf Avenue site at a discount of more than $50,000.[19] Once Reynolds acquired the site, he made a deal with the New York City Board of Estimate to demap West Eighth Street, which separated McKane's parcels from each other.[15] The street, which had taken up one-sixth of the proposed park's width, contained a trolley terminal that needed to be relocated.[15]

Originally, the park was supposed to be known as the Hippodrome.[8][15] In August 1903, Reynolds and several other men established the Wonderland Company, which had a capitalization of $1.2 million[16] and existed specifically to develop an amusement park on the site.[20][21] The amusement pier was planned to contain a dance hall and bathing pavilion, while the main portion of the site would be arranged around a large tower that would overtop Luna Park's.[22] The company took title to the plots in September 1903 and received a $200,000 mortgage loan from the Title Guarantee and Trust Company.[20][21] The Edison Company was hired to manufacture the park's lights in late 1903; the new park was expected to have more electric lights than had existed on all of Coney Island during the preceding season.[23][24]

Construction of the park itself began in December 1903.[18][22] General contractor Edward Johnson Company employed about 2,000 workers,[15] who were employed in three shifts of eight hours each.[8][22] The park was known as Dreamland by January 1904.[25] Reynolds, wishing to surpass Luna Park by every metric, reportedly spent $3.5 million on Dreamland.[8][26] Dreamland had one million lights, compared to 250,000 lights at Luna Park; even Dreamland's firefighting show was more elaborate than that at Luna Park.[27] Dreamland also planned to differentiate itself from Luna Park by adding novel attractions, as well as operating a private beach and bath house (something that Luna Park lacked because of its inland location).[8] Samuel W. Gumpertz was among those who helped develop the park.[28]

Operation

1904 to 1907

Dreamland opened on May 15, 1904,[29] with a fire show that employed 4,000 performers.[30] The park was $1.9 million in debt, more than the entire amount invested in the competing Luna Park. Dreamland charged 10 cents for admission on weekdays and 15 cents on weekends, plus an additional fee of up to 25 cents for individual rides.[8] The park closed for the season on September 24, 1904.[31][32] Reynolds said Dreamland had recorded a $400,000 net profit during the operating season,[32] despite erroneous reports that the park had been placed in receivership.[31] Although the Leapfrog Railway roller coaster was completed with the rest of the park, it did not open until the 1905 season.[8]

Reynolds spent $500,000 on new attractions and shows ahead of the 1905 season,[33][34] which ran from May 13[35] to September 24.[36] Among these was a show based on the Creation myth, which had been exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition;[37][38] this attraction alone cost $250,000.[33][34] The park also added an exhibition of a Roman hippodrome around the lagoon; replaced the submarine ride with the Hell Gate boat ride; and added a Japanese-themed theater.[33][38][39] City officials temporarily closed Dreamland's pier in May 1905, citing the fact that the pier was too narrow to accommodate crowds.[40][41]

Many of the park's shows were replaced for the 1906 season, and park officials also rebuilt the pier.[42] The new attractions for that season included a reenactment of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake's aftermath; a Moqui Indian village; a rebuilt Creation show;[42][43] and the Touring New York car show.[44] The park opened for the 1906 season on May 20,[42] and it began hosting vaudeville shows for the first time that June.[45] Dreamland's third season ended on September 24, 1906.[46] Prior to the 1907 season, concessionaire William Ellis introduced an attraction called the Orient, anchored by a theater that presented several shows.[47][48] Park officials also built a new administration building and installed other shows.[49] Park officials gave $50 to the first guest of the season on May 18, 1907,[49][50] and the park operated through September 21 of that year.[51] At this point, the park hosted several shows that were based on themes of morality,[52][53] such as "The End of the World" and the "Feast of Beshazzar and the Destruction of Babylon".[48][54]

1908 to 1911

Coney Island had reached its peak popularity by the late 1900s, when millions of people visited the neighborhood every year.[55] Despite its many amusements, Dreamland struggled to compete with the better-managed Luna Park.[56] As such, for the 1908 season, the park's management decided to offer free admission during weekdays;[57] although the free-admission policy did not extend to individual rides, the policy still attracted visitors.[58] The park opened for the season on May 23, 1908,[59][60] and operated until September 20.[61] For this season, Ellis added an auditorium with more than one thousand seats, and the park also added shows such as Freak Street, the Moroccan Jugglers, and an Old Virginia show.[59] Following the 1908 season, Dreamland hired Wells Hawks of the New York Hippodrome to lead the publicity bureau, and they hired Gumpertz as the general manager.[62]

Prior to the 1909 season, four thousand workmen completely revamped the park's attractions.[63] The ballroom was expanded to accommodate 1,500 couples.[62] Other additions included a wisteria garden on the site of the former hippodrome track, a circus ring near the tower, a scenic railway roller coaster,[62][63] a Deep Sea Divers attraction, and a village of Filipinos.[64] The park's operators said "everything at Dreamland will be new but the ocean".[64] The park's sixth season began on May 15, 1909,[65][66] and ended on September 19.[67][68] That year, New York City mayor George B. McClellan Jr. attempted to prevent the park from staging live shows on Sundays, citing the city's blue laws,[69][70] although Reynolds strongly opposed the legislation.[71][72] Dreamland had previously held a license permitting it to present shows seven days a week. When the license was renewed in June 1909, the shows were allowed only six days a week.[73] Gumpertz said the city government took issue with Dreamland's circus, which was free of charge.[74] City officials also objected to the Filipino villagers' attire, which exposed their legs.[75]

Kings County sheriff Patrick H. Quinn announced in February 1910 that the park would be auctioned off on behalf of Eugene Wood and Joseph Huber,[76][77] the corporation's two largest bondholders, who wanted to reorganize the company.[78] The auction only involved a nominal change of ownership, as Huber and Wood bought the park the next month.[79][80] Dreamland's seventh season began on May 14, 1910,[81][82] and ran until September 18.[83][84] Among the new attractions for the 1910 season were Alligator Joe's alligator and crocodile farm, a Bornean village, and a ride called Trip to the North Pole.[85][86]

In preparation for Dreamland's 1911 season, its operators made additional changes.[87] For instance, the buildings were repainted in white and red,[88][89] and the structures near the Surf Avenue entrance were demolished to make way for a lighting plant with 130,000 additional light bulbs.[90] Various rides such as the Great Divide, Canals of Venice, Tub Ride, and Hell Gate were enlarged,[91] while the ballroom and restaurant had been relocated from the pier to near the Surf Avenue entrance.[91][92] The site of the old ballroom was converted to a skating rink, and the bathing pavilion on the ocean was expanded significantly.[93][94] The park added thirty new shows,[95][96] such as Joseph Ferari's animal show, a biblical show known as the Sacrifice, and a village of "human curiosities".[93][94] It also added a miniature subway around the park, a carousel, and a dual-tracked roller coaster.[92] Some existing attractions were retained, such as Bostock's Wild Animals, which included a dwarf elephant named Little Hip and a one-armed lion tamer known as Captain Jack Bonavita.[97] Dreamland also hired Omar Sami as a carnival barker for the 1911 season,[98] and the park opened for its eighth season on May 20, 1911.[95][96][99]

Destruction

Fire

Despite the implementation of fire-safety regulations in certain areas of Coney Island after a major blaze in 1902, these regulations were not extended to Dreamland. Consequently, the park remained highly vulnerable to fire.[25] During the early morning of May 27, 1911, the Hell Gate attraction was undergoing last-minute repairs by a roofing company owned by Samuel Engelstein.[100] A leak had to be caulked with tar. During these repairs, at about 1:30 a.m.,[b] the light bulbs turned off and a worker kicked over a bucket of hot pitch, causing the light bulbs to explode.[101] Winds from the ocean caused the fire to quickly spread throughout the park.[101][102] The Dreamland fire was the first double-nine-alarm fire that the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) had ever fought in Brooklyn.[103][104][c] This alarm, which signified the most severe type of fire, summoned FDNY companies from across Brooklyn.[105]

Fires had been a persistent problem at Coney Island, so a high-pressure water pumping station had been constructed at West 15th Street near Coney Island Creek during the 1900s.[106] On the night of the Dreamland fire, the water pressure was extremely low:[107][108] the pumping station was capable of supplying water at 150 pounds per square inch (1,000 kPa), but the pressure had dropped to 35 pounds per square inch (240 kPa).[100] Furthermore, even though Coney Island's firehouse was within 100 yards (91 m) of Dreamland, the other FDNY companies had to travel long distances to reach Coney Island. By the time other FDNY companies reached the neighborhood, the entire park had caught fire.[108] As a result of the conflagration's intensity, as well as the low water pressure, firefighters could not even enter the park; they attempted to extinguish the fire from its borders.[109][110] As the park burned, tens of thousands of onlookers traveled from across New York City to see the fire.[107][109] Firefighters quickly shifted their focus to saving adjacent structures.[110] Several buildings on the south side of Surf Avenue caught fire, although almost all buildings on the north side remained undamaged.[107][109]

Bonavita and Ferari attempted to save the animals, some of whom escaped,[111][112] though about 60 animals died.[11] A lion named Black Prince rushed into the streets and climbed a roller coaster before being shot.[112][113] Another animal, Sultan, was shot several dozen times before being killed by an axe blow.[107][111] Early editions of The New York Times claimed the incubator babies had perished in the flames,[108] but the infants were all saved,[111] and the Times subsequently corrected itself.[114] According to contemporary accounts, New York City Police Department (NYPD) sergeant Frederick Klinck made several trips into the burning structure to rescue incubator babies.[107] The conflagration extended east to Balmer's bathing pavilion at West 5th Street and west to the new Giant Coaster at West 10th Street. The Giant Coaster acted as a firebreak that prevented the fire from spreading,[102][107] as did several brick buildings east of the park's central tower.[115] The tower collapsed just after 3 a.m.,[102] and all attractions were on fire by 3:30 a.m.[115] Around 4 a.m., the water pressure returned to normal, but most of the park had been burned by then.[102][103] The fire was extinguished at 5 a.m.[114]

Aftermath

The NYPD initially estimated that the park had sustained $4 million in damage,[107][103] although other estimates ranged between $2.25 and $5 million.[103] The fire destroyed almost everything in the park.[19] The Dicker family's adjacent hotel also burned down,[116] as did both of Dreamland's piers.[107][117] Only one building remained intact after the fire,[118] and all concessions were destroyed.[102] Conversely, the El Dorado Carousel, which had been relocated to the area shortly before the fire, survived relatively intact.[119] The entire complex had been constructed of combustible materials, so insurers saw the park as high-risk. The park was consequently insured for only about $400,000.[107][120] A preliminary investigation found that the fire had started when the tar spread across the floor, creating a short circuit that caused the light bulbs to explode.[100][117]

As a result of the fire, 1,600 Dreamland employees lost their jobs; another 900 people worked in neighboring businesses that had also been destroyed.[108] Hundreds of workers were clearing the site several hours after the fire had been extinguished,[117] and some of Dreamland's shows resumed on May 28, 1911, the day after the fire.[121][122] Coney Island attracted 350,000 visitors on that day; concessionaires attracted some of these visitors by exhibiting debris and dead animals,[121][122] and workers also tried to salvage the Giant Racing Coaster.[114] The New York State Legislature also introduced legislation to ban infant incubators in New York state's amusement parks.[100] The Dreamland fire negatively impacted its competitors' business, as the fire drove away visitors who would have gone to Dreamland.[123]

Condemnation proceedings

Immediately after the fire was extinguished, Reynolds indicated that he would not rebuild the burned park.[100][124] Two days after the fire, Reynolds proposed selling Dreamland's site to the New York City government for a "fair price", which would allow the city to convert the land to a public park.[125][126] The Times Union reported the price as $3 million,[127] but Reynolds denied these allegations.[128] He suggested that the New York City government could buy the 40-acre (16 ha) tract surrounding his park for that amount.[129] The New York City Board of Estimate began considering buying the Dreamland site in mid-June 1911,[130][131] and it voted to acquire the Dreamland site via condemnation at the end of July 1911.[132][133] The board approved a revised proposal that October in which it agreed to pay $1 million for a 7-acre (2.8 ha) site.[134][135] The revised proposal excluded the northernmost 200 feet (61 m) of Dreamland's site, on Surf Avenue, thereby splitting the park's site into two sections.[136] Brooklyn borough president Alfred E. Steers immediately advocated for selling the site and developing a boardwalk along the ocean.[137][138]

Legal disputes quickly arose over who held the Dreamland site's property title.[139][140] The Morey and Lott families claimed in late 1911 that nearly all of Coney Island fell under a quitclaim deed granted by Nicholas Johnson, who had agreed to sell the land even though he had no right to the property.[139] Barnet Morey's heirs sued Dreamland in February 1912,[141] and the city formed a condemnation commission the same month to determine how much compensation the former owners should receive.[142] The city took title to the Dreamland site in March 1912.[143] Although the condemnation commissioners began taking testimony that October,[142] the proceedings were delayed because of the lawsuit.[144][145] A New York Supreme Court justice dismissed the Morey and Lott families' lawsuit in May 1913,[146][147] and the Dreamland Company received $1,000 in damages.[148]

The condemnation commission announced in late 1914 that it would pay $2.189 million to property owners,[143][149] which included the Dreamland Company, the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad (PP&CI), and the Balmer family.[150][151] The award was revised downward to just over $2.1 million in June 1915,[152] but the city appealed the award, and the condemnation proceedings were delayed for years.[136] The New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, ruled in early 1916 that Dreamland Company's and PP&CI's awards were too high.[153][154] The city selected a second group of commissioners,[150] which decided in February 1919 to reduce the total award to $1.4 million.[155] The commissioners notified the state government of the revised award in October 1919;[156][157] by then, the cost of the condemnation itself had grown to $800,000.[142] The State Supreme Court was asked to confirm the revised award in June 1920, eight years after the condemnation proceedings had begun.[158][159]

Subsequent site usage

Northern section

By July 1911, independent concessionaires had rebuilt their booths on the northern portion of the site, facing Surf Avenue; the remainder of the park remained ruined.[160] The northern part of the site contained "a sideshow of freaks and some shooting galleries" in 1912.[161] Gumpertz leased the northern parcel in 1914, measuring 400 feet (120 m) on Surf Avenue and 200 feet (61 m) deep;[162] he intended to restore the attractions there.[163] By the next year, the northern part of the site had roller coasters, side shows, and shooting galleries named after Dreamland.[164] Film producer William Fox acquired the northern part of the site at an auction in March 1921 for $407,750,[165][166] and he resold it in June 1921 to Gumpertz and William M. Greve for $450,000.[167][168] Gumpertz and Greve planned to rebuild the park, although this never happened.[169]

Southern section

The southern section of the park was not redeveloped for several decades after the 1911 fire.[101] The remaining buildings on the southern part of the Dreamland site were razed by 1915.[170] The site was supposed to be part of the unbuilt Seaside Park.[171] The New York City government had planned to rebuild Dreamland's pier and fill it with rock;[172][173] the pier was supposed to be completed in mid-1914,[174] but two years later it still had not been rebuilt.[175][176] R. H. Pfoor proposed constructing a bathhouse on Dreamland's site in 1919, but city officials rejected the proposal.[177] The city government converted its portion of the site into a 1,000-by-60-foot (305 by 18 m) parking lot in 1921.[178][179] The city had expanded the parking lot to 2,000 spaces by 1922,[180] and it also operated a seasonal skating rink on Dreamland's site.[181] Morris Auditore and Harry Shea leased the site from the city in 1926;[182][183] the Supreme Court initially issued an injunction blocking the lease, but the Appellate Division reversed the injunction.[184][185] The next year, the New York City Board of Aldermen blocked a proposal for the city to either sell the land or convert it into some "public use".[186]

Auditore and Shea operated the parking lot until 1933, when their lease was canceled because they could not afford to pay $26,000 a year.[187] Although the Park Association of New York City suggested that the site be converted back into a public park, the city leased the parking lot to Irving Rosoff in February 1933.[188][189] City park commissioner Robert Moses canceled Rosoff's lease the next year.[190] By 1935, the city planned to rebuild Dreamland as an 11-acre (4.5 ha) recreation center with courts for handball, ping-pong, and shuffleboard, as well as a large open field for archery and other games. In addition, the recreation center was to contain more than 600 trees, as well as a connection to the Riegelmann Boardwalk, which was built along the Atlantic Ocean shoreline after Dreamland had been destroyed.[171][191]

The city government first considered relocating the New York Aquarium to the Dreamland site in 1941 after the closure of Castle Clinton, the aquarium's previous home in Manhattan.[192] Although plans for the new aquarium were announced in 1943,[193] it did not open until 1957.[194] The New York Aquarium occupies the entire Dreamland site.[101][195] A 500-pound (230 kg) bronze bell, which had been installed on Dreamland's pier until the 1911 fire, was recovered from the Atlantic Ocean in 2009. According to Charles Denson of the Coney Island History Project, the bell was the only surviving major remnant of Dreamland's pier.[196]

Description

The park was on a parcel between Surf Avenue to the north, West 5th Street to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and West 10th Street to the west.[107] At its peak, Dreamland had 14,000 employees and could accommodate at least 100,000 guests at once.[15] Everything in Dreamland was reputed to be bigger and more wide-ranging than in neighboring Luna Park.[8] Dreamland had a larger central tower and one million electric light bulbs illuminating and outlining its buildings,[197] four times as many lights as Luna Park.[11] An individual connected with the Edison Company said in 1903 that Dreamland's lighting contract was "the largest contract for lighting ever made in the United States, and I believe in the world".[23] Dreamland's illumination cost $4,000 a week; it cost $100 a night just to light the central tower.[108]

Manhattan-based architectural firm Kirby, Petit & Green designed Dreamland's buildings.[18][198] The structures were generally painted in light colors.[198] At the time of the park's opening, the buildings were reported to be clad with artificial stone,[15][198] and 1,700 short tons (1,500 long tons; 1,500 t) of asbestos fireproofing and 90 miles (140 km) of utility pipes were used.[15] However, the frames of the buildings were made of lath (thin strips of wood) covered with staff (a moldable mixture of plaster of Paris and hemp fiber).[11] Consequently, the entire park was highly susceptible to fire.[107] Throughout most of Dreamland's history, the attractions were painted white with small touches of green or yellow; the exception was the 1911 season, when the buildings were all repainted red and white.[89] Dreamland advertised itself as an educational attraction, as symbolized by its main entrance, which contained a female representation of education.[199]

Layout and attractions

The park was arranged roughly as a horseshoe, with a pier facing south toward the Atlantic Ocean.[18][26] Several rides were imitations of Luna Park's, such as a submarine ride and a Shoot-the-Chutes replica.[26] Multiple buildings, such as the Pompeiian, Electricity, and Submarine Boat buildings, were dedicated to exhibits.[18] New attractions were added every season.[19] To facilitate circulation, the paths were designed with gentle slopes and few steps.[200]

Entrance and lagoon

Dreamland's primary landside entrance was on Surf Avenue, where there was an arch measuring 150 feet (46 m) deep, 75 feet (23 m) high, and 50 feet (15 m) wide; the portal was intended to resemble a theater's proscenium arch.[18][15] There were several smaller, similarly designed portals along Surf Avenue.[18] Guests paid a ten-cent entry fee to pass through the gates, then paid an additional fee for the attractions.[15]

At the park's center was a lagoon surrounded by a promenade.[26] Originally, Dreamland's operators had planned to install flood gates that allowed salt water into the lagoon during high tide. The lagoon measured 130 feet (40 m) wide and 300 feet (91 m) long, spanned by a large pedestrian bridge at its southern end.[15] The footbridge over the lagoon had ornate columns with glass globes, as well as carved lions on either end. There was a miniature railway underneath the promenade.[18] The side shows were arranged around the lagoon.[201] Kirby, Petit & Green designed the buildings around the lagoon in numerous architectural styles that complemented each other, in contrast to Luna Park.[15] A hippodrome track was built around the lagoon in 1906.[33][39] The track was replaced with bathhouses by 1910, and a pergola was also constructed on the lagoon's shore.[15]

At the northern end of the lagoon was the Beacon Tower, a French Renaissance-style edifice[26][202] measuring 50 by 50 feet (15 by 15 m) square at its base and approximately 375 feet (114 m)[d] tall.[17][199][198][201] The tower's gold-and-white facade contained large arches; bas-reliefs carved by Perry Hinton; and 100,000 electric lights.[26][202] Elevators transported visitors to the roof,[198][201] which was decorated with a ball and eagle.[26] The tower contained water-storage tanks with a capacity of 600,000 U.S. gallons (2,300,000 L).[15] An attraction called Hiram Maxim's Airships was added just north of the tower in 1905;[15] it consisted of airships that were hung from a 150-foot (46 m) tower.[52]

East side

On the north side of the park, to the left of the Surf Avenue entrance, was a medieval-style entrance with a show called Our Boys in Blue.[198] Another structure, just south of Our Boys in Blue, hosted an illusion presented by Ben Morris.[15] Just right of the entrance, at the park's northeast corner, was Bostock's wild animal exhibit,[17][26] housed in a Grecian-style structure with motifs of wild animals.[18] Next to this structure was another edifice that contained the Chilkoot Pass attraction,[18][30] which was essentially a massive bagatelle board where guests used their own bodies to play the game.[30][204] The Chilkoot Pass building was situated within a classical-style structure whose main entrance resembled a proscenium arch.[18] The Haunted Swing and Funny Room were housed within a Mission Revival-style building next to the Chilkoot Pass.[18][30][205] South of that was a fishing pond operated by comedian Andrew Mack, located inside a building that resembled a boat and a lighthouse.[18][205]

East of the lagoon, next to the fishing pond, was an imitation of Venice made of papier-mâché;[199] it featured canals with gondolas, as well as a replica of Doge's Palace.[18][26] The latter building housed the Canals of Venice ride,[205] which contained additional replicas of various Venetian landmarks.[18][201] Next to the Doge's Palace was a scenic railway called Coasting Through Switzerland, which ran through a Swiss alpine landscape.[19] The scenic railway building was designed in the Art Nouveau style,[17][30] with a golden proscenium arch measuring 60 feet (18 m) wide and 30 feet (9.1 m) high.[18][205] Attached to Coasting through Switzerland was a structure housing the Fighting the Flames show, where two thousand people pretended to put out a fire every half-hour.[18] The show building, measuring 520 by 250 feet (158 by 76 m),[198][205] was meant to resemble a seven-story hotel and several small stores;[18] it was replaced in 1906 by a show themed to that year's earthquake in San Francisco.[43]

West side

Near the park's southwest corner was a human zoo called the "Lilliputian Village", designed as an imitation of a 15th-century German village.[17] It was populated by three hundred little people,[199][206] who had their own livery tent, stable, laundry, and fire department.[30][206] Next to the Lilliputian Village was the Destruction of Pompeii, a Greek-style structure with an exhibit that displayed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.[18] An adjacent structure, the Electricity Building, had a facade that depicted machinery;[18] the building contained the park's actual mechanical plant.[15] A third structure, next to the Pompeian and Electricity buildings,[18][205] housed a submarine ride called Over and Under the Sea;[18][26] the submarine ride was replaced in 1905 by the Hell Gate boat ride, which featured a whirlpool.[33] LaMarcus Adna Thompson's Thompson Scenic Railway, which predated the park, was accessed via an Art Nouveau-style structure.[15]

The attractions on the southwestern corner of the park were replaced in 1907 with the Orient attraction, which consisted of a massive staff arch measuring 200 feet (61 m) high, as well as a series of structures surrounding a theater.[15] In addition, in 1909, Gumpertz added a "Filipino village" which featured two hundred Igorot hunters.[56]

A building with baby incubators, designed as a German farmhouse, was at the park's northwest corner. The lower half of the building was clad in brick. By contrast, the upper half had a timber facade and a tiled gable roof.[26][30] The baby-incubator building cared for and exhibited premature babies,[207] including triplets who were members of the Dicker family. At the time, the technology was not allowed in hospitals, but the incubators were allowed in side shows; two of the triplets survived to adulthood.[26] Yet another building housed Wormwood's Dog and Monkey Show,[26] housed in a building that was decorated with motifs of monkeys and dogs.[17][30]

Oceanfront

Dreamland's oceanfront pier contained a structure with a restaurant and a ballroom.[198] The ballroom was supposedly the largest in New York state at the time of its construction;[15] it spanned 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2),[18][199] with dimensions of about 100 by 250 feet (30 by 76 m),[18] and was surrounded by a balcony.[17][30] The ceiling of the ballroom measured 50 feet (15 m) high[202] and had 10,000 lightbulbs.[199] Adjoining the ballroom was the restaurant, measuring 60 by 240 feet (18 by 73 m).[18] The lower part of the structure was a ferry landing with booths and small shows.[201] When Dreamland opened, the landing was served by ferry lines to Harlem, 23rd Street, and the Battery in Manhattan;[17][18] the ferry rides cost up to 35 cents, but that price included admission.[15] The lower deck of the pier was known as the Bowery,[17][18] a replica of Manhattan's Chinatown, which the Times Union described as a place where "the lid will be off".[198] The adjoining segment of the Coney Island Beach was originally a private beach.[8]

The oceanfront featured a Japanese building, a two-story structure capped by a central tower, which led to an airship attraction and some tea rooms.[18][205] The airship attraction was an exhibition of Santos-Dumont Airship No. 9.[205] Another show, called the Seven Temptations of St. Anthony,[18] was targeted toward male guests.[15] At the foot of the park's lagoon were two Shoot-the-Chutes with two ramps that could handle 7,000 hourly riders.[26] Two boats, each carrying 20 people, slid down the ramps,[26][202] which extended 300 feet (91 m) into the ocean.[199] Another oceanfront attraction was the Leap-Frog Railway, a switchback railway-style attraction on a 500-foot-long (150 m) pier, where two 40-person carts were accelerated toward each other at high speed before passing each other at the last second.[18][202][208]

Concessions

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In a bid for publicity, Reynolds awarded a concession for the park's peanut-and-popcorn stands to Broadway actress Marie Dressler,[209] with young boys dressed as imps in red flannel acting as salesmen. Dressler may have been in love with Captain Jack Bonavita, Dreamland's one-armed lion tamer.[197] Bonavita, who commanded lions in the Bostock animal arena, had one arm amputated after his hand was severely clawed by one of the lions and a blood infection spread through that hand.[11]

Impact

When Dreamland opened, the New-York Tribune wrote: "Nothing but a personal visit and inspection can do anything like justice to the subject."[18] A writer for The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called Dreamland "a city of amusement in itself", which was successful because of "the intelligent use of unlimited money expended for the best interest of unnumbered patrons in search of innocent amusement".[200] During its last full season of operation, in 1910, a writer for Billboard said: "It's a great big Dreamland this year, and it's good clean through".[210] The writer Marcia Reiss wrote in 2014 that the park was a "dazzling white city", calling it "Coney Island's grandest and shortest-lived amusement park".[199] The design of Dreamland also inspired the creation of similar amusement parks around the world, such as Magic-City in Paris.[211]

The park has been depicted in various works of popular culture. Artist Philomena Marano created a body of work inspired by the park in the papier collé method, American Dream-Land.[29][212] Brian Carpenter wrote a play treatment which he used as a springboard for lyrics and compositions behind his second studio album for Beat Circus entitled Dreamland. The album featured Todd Robbins, an alumnus of Coney Island, and its booklet includes historical images of Dreamland donated by the Coney Island Museum.[213] The Public Theater also staged the play Fire in Dreamland in 2018, which is based on the park's 1911 conflagration.[214][215]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ According to Jeffrey Stanton, one of McKane's parcels cost $200,000, while the other cost $247,000.[15]

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 83, cites the fire as having started at 1:45 a.m.

- ^ Prior to the Dreamland fire, the FDNY had only ever responded to one other "two-nine" fire in 1904, when the Adams Express Building burned down.[105]

- ^ Some sources give an alternate height of 370 feet (110 m).[202]

Citations

- ^ Goldfield, David R. (2006). Encyclopedia of American Urban History. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7. OCLC 162105753.

- ^ Kasson 1978, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Parascandola 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 56.

- ^ "Luna Park First Night – Coney Island Visitors Dazzled by Electric City – Many Colored Illuminations and Canals – A Midway of Nations and a Trip to the Moon Replace the Old-Time Recreations". The New York Times. May 17, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 10, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Immerso 2002, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sullivan, David A. "Dreamland (1904–1911)". Heart of Coney Island. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Sandy, Adam (1996–2012). "Roller Coaster History: Early 1900s: Coney Island". Ultimate Roller Coaster. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Walkabout: William H. Reynolds, conclusion". Brownstoner. May 6, 2010. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "At Hell's Gate: The Rise and Fall of Coney Island's Dreamland". Entertainment Designer. February 4, 2012. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Coney Island Hippodrome; Syndicate Purchases Land for a Big Amusement Park on the Shore". The New York Times. July 18, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 10, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Big Coney Island Resort Planned for Next Season". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 17, 1903. p. 16. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Work of Rebuilding Coney Island's Bowery Started". The Standard Union. November 3, 1903. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Stanton, Jeffrey (April 6, 1998). "Coney Island: Dreamland". Westland. Archived from the original on October 18, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "'Wonderland' for Coney". Times Union. August 20, 1903. p. 10. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "'Dreamland, By the Ocean', Thronged with Visitors". The Standard Union. May 15, 1904. p. 11. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Dreamland-by-the-sea". New-York Tribune. May 15, 1904. p. 26. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "All Attractions Gone or Charred". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 27, 1911. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Wonderland Mortgage". The Brooklyn Citizen. September 25, 1903. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Wonderland at Coney Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 25, 1903. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Coney's Wonderland". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 17, 1903. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Largest Light Contract Ever Made". Times Union. November 11, 1903. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Record-Breaking Electric Contract". Times Union. December 17, 1903. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Coney Preparing for the Season". The Standard Union. January 21, 1904. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Immerso 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Berman, J.S.; Museum of the City of New York (2003). Coney Island. Portraits of America. Barnes and Noble Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7607-3887-0. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "S. W. Gumpertz Is Dead; Gave Ziegfeld a Start: Managed Houdini and Built Coney Island Dreamland; Ran the Ringling Circus". New York Herald Tribune. June 23, 1952. p. 18. ProQuest 1322451669.

- ^ a b Denson, Charles, Coney Island Lost and Found, Ten Speed Press, 2002, pages 227–231

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "New Coney Dazzles Its Record Multitude; Luna Park and Dreamland the Centres of Great Crush". The New York Times. May 15, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "No Dreamland Receivership; This Coney Island Corporation on an Absolutely Solvent Basis". The New York Times. September 25, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Coney Island Season Ends to-day: Mr. Reynolds Denies Story of Receiver for Dreamland--says Profits Were $400,000". New-York Tribune. September 25, 1904. p. 7. ProQuest 571501013.

- ^ a b c d e "Great New Dreamland at Coney This Year; New Features at Resort Put In at Cost of $500,000". The New York Times. April 23, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Big Improvements at Dreamland: Bonavita Back--how He Fought His Last Fight With Right Arm". New-York Tribune. April 23, 1905. p. 4. ProQuest 571554145.

- ^ "Chilly Damp Spoils Coney Season's Bow; Dreamland and Luna Park Brighter Than Ever". The New York Times. May 14, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "The Stage". The Standard Union. September 24, 1905. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coney Island Sees "Creation.": Show Imported From St. Louis Opens at Dreamland". New-York Tribune. May 30, 1905. p. 7. ProQuest 571622108.

- ^ a b "Night Scene at Coney to be Greater than Ever". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 30, 1905. p. 60. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Luna Park and Dreamland: This Year's New Features Among Coney Island's Most Popular Amusements". Town and Country. Vol. 60, no. 18. July 8, 1905. p. 23. ProQuest 2092500035.

- ^ "Closes Dreamland Pier: Commissioner Featherson Calls It Dangerous". New-York Tribune. May 17, 1905. p. 4. ProQuest 571523427.

- ^ "Boxing, Bag Punching, When Police Break in; 400 Persons Watch Impromptu Athletic Events in Poolroom". The New York Times. May 17, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Dreamland Reopens and Shows New Glories; Spectacles Range from Creation to the End of the World". The New York Times. May 20, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "New Wonders at Coney: All Parks Improved Dreamland, Luna and Brighton Perking Up for Summer Dreamland a New Park Wild West at Brighton". New-York Tribune. May 6, 1906. p. 5. ProQuest 571566767.

- ^ Hill, Walter K. (June 9, 1906). "Dreamland the Beautiful is Pearl of Coney Island". The Billboard. Vol. 18, no. 23. p. 6. ProQuest 1505502927.

- ^ "Dreamland, Coney Island". Variety. Vol. 3, no. 1. June 16, 1906. p. 10. ProQuest 1529031002.

- ^ "Coney Island Season Closes". New-York Tribune. September 25, 1905. p. 5. ProQuest 571877383.

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 74.

- ^ a b "New Wonders This Season at Coney Island". The New York Times. April 21, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Dreamland Now Open: Prize of $50 Given to First Woman to Enter Park". New-York Tribune. May 19, 1907. p. 5. ProQuest 572020079.

- ^ "A New Dreamland at Coney Island; Many Additional Attractions and 1,000,000 Lights Mark 4th Season's Opening". The New York Times. May 19, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Coney's Great Carnival to End To-night". The Evening World. September 21, 1907. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Immerso 2002, p. 73.

- ^ "Coney Island". PBS. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "New York's Great Seaside Resort: Coney Island, With Its Huge Amusement Parks, Dreamland and Luna Park, at the Height of Its Popularity in Spite of Destructive Fires". Town and Country. No. 3194. August 3, 1907. p. 26. ProQuest 126887439.

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 81.

- ^ a b Immerso 2002, p. 82.

- ^ "Coney Island Opens for Summer Fun". The New York Times. May 17, 1908. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland Proving More Popular Daily". The Standard Union. June 30, 1908. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Coney Island Hippodrome Circus". The New York Times. May 24, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Dreamland Ablaze: Crowds Penetrate Fog Steeplechase, Tod, Once More Fun-making at Coney Island". New-York Tribune. May 24, 1908. p. 2. ProQuest 572085031.

- ^ "Big Coney Island Parks Close for the Season". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 21, 1908. p. 10. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Will Be "Greater Dreamland.": Big Coney Island Park Has Been Reconstructed and Win Open May 15". New-York Tribune. April 25, 1909. p. 9. ProQuest 572170798.

- ^ a b "Dreamland Made Over; Coney Island Resort Transformed Since Last Season". The New York Times. April 25, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "Coney Island's Day". New-York Tribune. May 9, 1909. p. 59. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Police Cut Short Coney's Opening Day; Make Shows and Concert Halls Close at Midnight and Disappoint 125,000". The New York Times. May 16, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Coney Island Opened: Resort in Full Swing Superstition Holds Shut Gates of Luna Park for an Hour". New-York Tribune. May 16, 1909. p. 3. ProQuest 572231671.

- ^ "Coney Island Season Ends; Police Have to Drive Away 10,000 Mardi Gras Revelers". The New York Times. September 20, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Farewell at Island: Bands' Last Serenade Police Broom Sweeps Resort Clean Before Dawn of Sunday". New-York Tribune. September 20, 1909. p. 3. ProQuest 572315576.

- ^ "Stop Sunday Shows at Coney Island; Bingham Says He Has Told the Police to See That the Law Is Strictly Enforced To-morrow". The New York Times. May 22, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ "Mayor Takes a Hand: Coney Island Shows Limits Licenses to Six Days to Test Justice Carr's Decision". New-York Tribune. May 18, 1909. p. 3. ProQuest 572175923.

- ^ "Stop Sunday Shows at Coney Island; Bingham Says He Has Told the Police to See That the Law Is Strictly Enforced To-morrow". The New York Times. May 22, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Coney Island Protest: Mass Meeting Appeals to the Mayor Mcclellan Says Enforcement of Laws is Up to the Police and Indicates No Wavering". New-York Tribune. May 22, 1909. p. 3. ProQuest 572223319.

- ^ "Mayor Wars Again on Sunday Shows; New Policy, in Granting Only Six-Day Licenses, Disclosed in Court Affidavit". The New York Times. June 24, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Coney Managers Stirred to Protest; See Ruin Ahead in the Strict Enforcement of Early-Closing Laws in the Resort". The New York Times. May 18, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Bronze Bare Legs Taboo". The Sun. May 31, 1909. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland to be Sold at Auction by Sheriff". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 14, 1910. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland to Be Sold". The Billboard. Vol. 22, no. 9. February 26, 1910. p. 28. ProQuest 1031408019.

- ^ "Dreamland Sold at Auction". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 30, 1910. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland at Auction". New-York Tribune. March 31, 1910. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field". The New York Times. March 31, 1910. p. 16. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coney Island Opens Up: Season Starts Auspiciously in Blaze of Lights and Noise 100,000 Throng Resort All the Old Shows and Many New Ones in Dreamland, Luna Park and the Others". New-York Tribune. May 15, 1910. p. 12. ProQuest 572374365.

- ^ "Coney Island Opens in Its Overcoat; Chill Breezes Blow in from the Ocean and the Holiday Throng Shivers". The New York Times. May 15, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Coney Island Season Ends: More Than 400,000 Persons at Resort on the Last Day". New-York Tribune. September 19, 1910. p. 2. ProQuest 572389732.

- ^ "Last of Coney Fun for Another Year; The Island Winds Up Its Season and the Purveyors of Pleasure Exchange Farewells". The New York Times. September 19, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Luna and Dreamland to Open May 14". The New York Times. May 1, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Greater Dreamland". The Billboard. Vol. 22, no. 19. May 7, 1910. p. 29. ProQuest 1031413324.

- ^ Berman, John S. (2003). Portraits of America: Coney Island. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, Inc. p. 36. ISBN 9780760738870.

- ^ "New Color Scheme at Dreamland". The Billboard. Vol. 23, no. 15. April 15, 1911. p. 73. ProQuest 1031420180.

- ^ a b "New Colors for Dreamland". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 5, 1911. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Big Changes at Dreamland". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 20, 1911. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Many New Attractions Installed During Spring; Record Season Expected". Times Union. May 27, 1911. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Greater Dreamland". Times Union. May 20, 1911. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Plays of the Week". Times Union. May 13, 1911. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Dreamland's Opening". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 14, 1911. p. 30. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Brooklyn and the Beaches". The Sun. May 21, 1911. p. 27. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Greater Dreamland". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 21, 1911. p. 17. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Immerso 2002, pp. 82–83.

- ^ "Omar Sami, the King of the Ballyhoos". Times Union. May 23, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Summer Surely is Here". New-York Tribune. May 21, 1911. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Coney Disaster Probe is Now in Progress; Brophy Investigating". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 28, 1911. pp. 1, 7. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Reiss 2014, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e "Poor Water Pressure Blamed for Big Loss by Flames at Coney". The Evening World. May 27, 1911. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Fire Loss Put as High as $5,000,000". New-York Tribune. May 28, 1911. pp. 1, 6. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rang 'Two Nines' for Dreamland Fire; First Time the Call Ever Was Sounded for a Fire in Brooklyn Borough". The New York Times. June 4, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "'Two-Nine' Used Seldom". New-York Tribune. May 28, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Temporary Lighting Outfit". The Insurance Press. Vol. 32. F. Webster. 1911. p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Coney Island Fire Ruins Dreamland; Loss $4,000,000". Times Union. May 27, 1911. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Flames Sweep Coney Island; Blaze Starts in Dreamland, Spreads Rapidly, and Park Is Soon Wholly Wiped Out". The New York Times. May 27, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Coney Island Holocaust". The Billboard. Vol. 23, no. 22. June 3, 1911. pp. 3, 55. ProQuest 1031428446.

- ^ a b Immerso 2002, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c Immerso 2002, p. 83.

- ^ a b "Coney's Ten-acre Fire Cost $3,225,000". The Sun. May 28, 1911. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Seitz, Sharon; Miller, Stiart (2011). The Other Islands of New York City: A History and Guide (3rd ed.). Countryman Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-58157-886-7. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Start Up Again in Coney Ruins; Temporary Shacks Grow in Gaping Hole Where Flames Took $5,000,000 Toll". The New York Times. May 28, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Immerso 2002, p. 84.

- ^ "New Fire Scare at Coney". The New York Times. July 28, 1911. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Tents and Frame Shacks Will Rise on Fire Ruins". The Standard Union. May 28, 1911. pp. 1, 4. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Early Coney Fires Razed Large Areas Dreamland Was Burned in 1911 With Damage Estimated at More Than $5,000,000". The New York Times. July 14, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Immerso 2002, pp. 84–85.

- ^ "Coney Island Poor Risk". New-York Tribune. May 28, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Fully 350,000 Flock to Coney". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 29, 1911. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Ruins Help Draw 350,000 to Coney; Ferari Exhibits in the Ashes of Dreamland the Few Beasts He Saved". The New York Times. May 29, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Coney's Future Not in Danger". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 7, 1912. p. 11. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 85.

- ^ "Aldermen Will Consider Seaside Park Extension Evening World Proposed". The Evening World. May 29, 1911. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Would Sell Dreamland to City at 'Fair Price'". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 29, 1911. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "City Won't Buy Dreamland Site". Times Union. May 30, 1911. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland Site Available for City; Company Willing to Sell at Reasonable Price, but Seeks a Plan of Operation". The New York Times. May 30, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Reynolds Talks Values: Says City Can Buy 40-acre Tract at Island for $3,000,000 Sum Includes Dreamland A. R. Schorer Discusses Purchase of Land Between Burned Area and Seaside Park". New-York Tribune. June 4, 1911. p. 7. ProQuest 574782176.

- ^ "Takes Up Seaside Park: Board of Estimate Considers Purchase of Coney Island Site Committee to Investigate Controller and Associates to Report on Advisability of City Buying Fireswept Property". New-York Tribune. June 16, 1911. p. 14. ProQuest 574780758.

- ^ "Coney Island Park a Costly Project; City Would Have to Pay Twelve or Fifteen Millions at Least to Get the Land". The New York Times. June 18, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Take Dreamland Site: Estimate Board Adopts Plan for a Seaside Park". New-York Tribune. July 28, 1911. p. 7. ProQuest 574786524.

- ^ "City Decides to Buy Two Seaside Parks; Dreamland Property and a Mile of Beach at Rockaway to be Acquired". The New York Times. July 28, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Two Seaside Parks to Be Bought by City; Estimate Board Votes to Take Dreamland Site and 250 Acres at Rockaway Beach". The New York Times. October 20, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "New York City to Buy Two Big Seaside Parks". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 19, 1911. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Mitchel Refutes Rockaway Charge". The Sun. October 1, 1917. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Steers for Walk at Coney Island". The Standard Union. November 16, 1911. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "For Coney Island Walk: Steers Hopes to Push Project Through for Next Summer". New-York Tribune. November 26, 1911. p. B2. ProQuest 574829997.

- ^ a b "Coney Island: Suit Involves Title to Famous Land Dunes Value is Reckoned High in Millions Was First Transferred to Dutch in 1645 Blanket and Gun Price". Courier-Journal. December 10, 1911. p. A16. ProQuest 1016425289.

- ^ "Sue for Coney Island: Descendants Say Former Owners Never Sold Land". New-York Tribune. February 17, 1912. p. 14. ProQuest 574885635.

- ^ "The Fight for Coney Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 24, 1912. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "7 Years Condemning Dreamland; Costs Continue to Pile Up". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 1, 1919. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "$2,189,169 for Coney Park; Award of $1,035,000 Fixed for Dreamland by Commissioners". The New York Times. November 20, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Who Owns Coney Island?; Suit Instituted Affecting Title to Property Valued at $100,000,000". The New York Times. October 27, 1912. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Coney's Ownership Now Up to Court". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 24, 1912. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Morey-Lott Heirs Lose Coney Suit". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 6, 1913. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Big Coney Island Land Claim is Dismissed". Times Union. May 6, 1913. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fight for Coney Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 23, 1913. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland Award Fixed: $2,197,701 Set as Condemnation Price for C. I. Park Site". New-York Tribune. November 20, 1914. p. 3. ProQuest 575301505.

- ^ a b "Dreamland Board Not Yet Sworn In". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 1, 1916. p. 14. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Settlement is Near in Dreamland Matter". The Standard Union. May 31, 1920. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland Park Final Award Fixed at $2,129,327.76". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 11, 1915. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Court Upholds Title Co.; Declares Owner Responsible for His Own Encroachment". The New York Times. March 18, 1916. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Dreamland in Bad Way Now". Times Union. March 18, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Reduce Dreamland Awards by $400,000". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 27, 1919. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 30, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fix Awards for Dreamland Park at $1,457,248". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 16, 1919. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coney Island Award Made". New York Herald. October 17, 1919. p. 11. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coney Awards Net $2,000,000". Times Union. June 16, 1920. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ask Confirmation of Park Awards". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 18, 1920. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Events of the Amusement Week in New York: Dreamland Again Active". The Billboard. Vol. 23, no. 30. July 29, 1911. pp. 8, 60. ProQuest 1031427088.

- ^ "City Leads World in Beach Resorts; New Yorkers Have a Score of Splendid Pleasure Grounds to Choose From". The New York Times. July 28, 1912. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Dreamland Pier to Be Used Again This Summer". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 24, 1914. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Will Revive Dreamland". The Billboard. Vol. 26, no. 3. January 17, 1914. p. 3. ProQuest 1040292589.

- ^ "Coney Island Opens Its Summer Season; Luna Park and Steeplechase, in New Guise, Receive First Crowds of Year". The New York Times. May 23, 1915. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Dreamland is Sold to Fox Syndicate". The Standard Union. March 22, 1921. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Last of Dreamland Sold for $407,750; Remainder of Park Property Not Acquired by City Bought by Bondholders". The New York Times. March 23, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Dreamland Site is Sold Again". Times Union. May 24, 1921. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "$450,000 for Dreamland; Syndicate Pays Fox Company $43,000 Profit on Recent Turnover". The New York Times. June 9, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Old Dreamland Park at Coney Is To Be Rebuilt". New-York Tribune. June 9, 1921. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coney Island Much Changed". Times Union. May 29, 1915. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Dreamland Parking Space to Become Recreation Spot". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 7, 1935. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Work on Plans to Raise a New Coney from Sea". Times Union. May 24, 1913. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Plan to Patch Up Dreamland's Pier". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 13, 1913. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland Pier to be Used Again This Summer". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 24, 1914. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dreamland Lease Withdrawn". The Christian Science Monitor. March 8, 1916. p. 7. ProQuest 509605700.

- ^ "Fairs and Expositions: Dreamland Pier". The Billboard. Vol. 28, no. 13. March 25, 1916. p. 31. ProQuest 1031505638.

- ^ "Disapproves Bath House at Dreamland Park". Times Union. July 17, 1919. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Auto Park for Coney Island". The Brooklyn Citizen. June 19, 1921. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Parking Space at Coney; Concourse 1,000 by 60 Feet Being Made Ready for Motorists". The New York Times. June 19, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Parking Space for 2,000 Autos at Coney Will Give Sea Breezes to Many Motorists". The New York Times. July 2, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Biggest Free Skating Rink in Country To Be Opened This Winter at Coney Island". The New York Times. October 14, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Coney Parking lease Fought as Unfair to City". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. March 27, 1926. p. 13. ProQuest 1112746573.

- ^ "Walker Backs Lease of Coney Island Site; Mayor Says Browne Used Good Judgment in Letting Dreamland Park Area for Autos". The New York Times. March 31, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "High Court Upholds Auto Park at Coney; Injunction Against Concession of City's Dreamland Space Is Reversed". The New York Times. June 26, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Auto Parking Lease Of Coney Dreamland Approved by Court: Appellate Division Unanimous in Vacating Injunction, Holding Place for Cars Is a Public Necessity". New York Herald Tribune. June 26, 1926. p. 2. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1112564414.

- ^ "Pratt Park Plan Loses; Tammany Aldermen Defeat Woman's Project for Dreamland". The New York Times. February 9, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Park Area Urged for Coney Island; Straus Asks Browns to Lease Only Half of Dreamland Tract for Automobiles". The New York Times. February 23, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Dreamland Park Leased at Good Bid; Rosoff Nephew Gets Parking Concession for Three Years at $23,150 Annually". The New York Times. February 24, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Refuses Delay in Park Auction". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 23, 1933. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Moses Revokes Rosoff's Coney Parking Permit: Operators of Dreamland Concession $5,000 Back in Rent, Park Head Says City to Take Over Space Lessees Hold Money Was Refused by Commissioner". New York Herald Tribune. May 1, 1934. p. 18. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1114850390.

- ^ "Coney Island Park is Planned by City; Dreamland Auto Space Will Be Converted Into an 11-Acre Recreation Centre". The New York Times. April 7, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Aquarium Weighs Coney Island Site; City Considers Erection of New $2,000,000 Exhibition Hall Fronting on Boardwalk". The New York Times. May 3, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Plans Announced for Oceanarium; Coney Island Project, to Cost $1,500,000, Cover 10 Acres, Will Replace Aquarium". The New York Times. July 28, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "New Aquarium Opens; Coney Island Building Draws More Than 8,000 in Day". The New York Times. June 7, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Remembering Parks Past". The New York Times. July 7, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (October 6, 2009). "After 98 Years Underwater, a Coney Island Bell Is Back". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Edo McCullough (1957). Good Old Coney Island: A Sentimental Journey Into the Past – the Most Rambunctious, Scandalous, Rapscallion, Splendiferous, Pugnacious, Spectacular, Illustrious, Prodigious, Frolicsome Island on Earth. Fordham University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780823219971. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Coney Island, With New Attractions, Most Amazing Yet, Open for Business Next Week". Times Union. May 7, 1904. pp. 6, 7. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Reiss 2014, p. 19.

- ^ a b "Dreamland, the Architectural Beauty Spot of Coney Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 12, 1904. p. 20. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Coney's Latest Big Show Will Open Next Saturday". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 8, 1904. p. 13. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "A New Coney Island Rises From the Ashes of the Old". The New York Times. May 8, 1904. p. 29. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Michael Immerso, Coney Island: The People's Playground, Rutgers University Press, 2002, page 73

- ^ Immerso 2002, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Dreamland, Coney's Venice, Reveals Its Charms to the Multitude". The Brooklyn Citizen. May 15, 1904. p. 14. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Immerso 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Halley, Catherine (August 15, 2018). "Coney Island's Incubator Babies". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Immerso 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ^ "Marie Dressler Gets Coney Peanut Privilege". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 18, 1904. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Brandt, Joseph (May 21, 1910). "Coney Island Opens". The Billboard. Vol. 22, no. 21. pp. 16, 40–41. ProQuest 1031406201.

- ^ "Paris's Magic City Opens; American Amusement Park on the Seine Built on Lines of Dreamland". The New York Times. June 3, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Breuckelen Magazine Video "Interview with Philomena Marano" Archived July 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine June 2014

- ^ Webster, Sarah (February 1, 2008). "Circus Coming To Town". Asbury Park Press. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ "Explore The 1911 Fire That Burned Coney Island To Ashes". Gothamist. July 10, 2018. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Clement, Olivia (July 16, 2018). "Watch Highlights From Fire in Dreamland". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

Sources

- Immerso, Michael (2002). Coney Island: the people's playground (illustrated ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3138-0.

- Kasson, John F. (1978). Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century. American century series. Hill & Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-2617-3.

- Parascandola, L.J. (2014). A Coney Island Reader: Through Dizzy Gates of Illusion. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53819-0.

- Reiss, Marcia (2014). Lost Brooklyn. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-1-909815-66-7. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0511-5. OCLC 9829395.

External links

- Dreamland at amusement-parks.com

- Maps and postcards of Dreamland

- Dreamland Park History

- Dreamland and William Reynolds at Heart of Coney Island

- Panoramic photo, "Destruction of Dreamland", 1911, from the Library of Congress

- Oral histories about Dreamland (1904–1911) collected by the Coney Island History Project