Critical analysis of the impact of AI on the patient–physician relationship: A multi-stakeholder qualitative study

Contents

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, smoked, inhaled |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

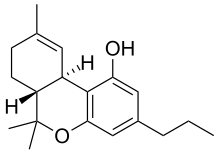

| Formula | C19H26O2 |

| Molar mass | 286.415 g·mol−1 |

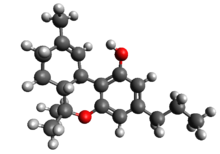

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV, THV, O-4394, GWP42004) is a homologue of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) having a propyl (3-carbon) side chain instead of pentyl (5-carbon), making it non-psychoactive in lower doses. It has been shown to exhibit neuroprotective activity, appetite suppression, glycemic control and reduced side effects compared to THC, making it a potential treatment for management of obesity and diabetes.[1] THCV was studied by Roger Adams as early as 1942.[2]

Natural occurrence

THCV is prevalent in certain central Asian and southern African strains of Cannabis.[3][4]

Chemistry

Similar to THC, THCV has 7 possible double bond isomers and 30 stereoisomers (see: Tetrahydrocannabinol#Isomerism). The alternative isomer Δ8-THCV is known as a synthetic compound with a code number of O-4395,[5] but it is not known to have been isolated from Cannabis plant material.

Description

Plants with elevated levels of propyl cannabinoids (including THCV) have been found in populations of Cannabis sativa L. ssp. indica (= Cannabis indica Lam.) from China, India, Nepal, Thailand, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, as well as southern and western Africa. THCV levels up to 20% of total cannabinoids have been reported.[2]

THCV is a cannabinoid receptor type 1 antagonist or, at higher doses, a CB1 receptor agonist and cannabinoid receptor type 2 partial agonist.[6] Δ8-THCV has also been shown to be a CB1 antagonist.[7] Both papers describing the antagonistic properties of THCV were demonstrated in murine models. THCV is an antagonist of THC at CB1 receptors and lessens the psychoactive effects of THC.[8]

THCV also acts as an agonist of GPR55 and l-α-lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI), and beyond the endocannabinoid system, THCV also activate 5-HT1A receptors to produce an antipsychotic effect, that has shown therapeutic potential for ameliorating some of the negative, cognitive and positive symptoms of schizophrenia. THCV furthermore interacts with different transient receptor potential (TRP) channels including TRPV2, which may contribute to the analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects of cannabinoids and Cannabis extracts. It has also shown anti-epileptiform and anticonvulsant properties, that suggest possible therapeutic application in the treatment of pathophysiologic hyperexcitability states such as untreatable epilepsy.[9]

THCV is found to inhibit the activity of both fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacyl glycerol lipase (MGL), even at micromolar concentrations, and thereby able to inhibit the hydrolysis of the endocannabinoids anandamide (AEA: C22H37NO2; 20:4, ω-6) besides other N-acylethanolamines and 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG: C23H38O4; 20:4, ω-6), respectively, therefore, it can also act as an indirect agonist at the cannabinoid receptors, by enhancing the activity of the endocannabinoid system (ECS).[10][11]

Biosynthesis

Unlike THC, cannabidiol (CBD), and cannabichromene (CBC), THCV doesn't begin as cannabigerolic acid (CBGA). Instead of combining with olivetolic acid to create CBGA, geranyl pyrophosphate joins with divarinolic acid, which has two fewer carbon atoms. The result is cannabigerovarin acid (CBGVA). Once CBGVA is created, the process continues exactly the same as it would for THC. CBGVA is broken down to tetrahydrocannabivarin carboxylic acid (THCVA) by the enzyme THCV synthase. At that point, THCVA can be decarboxylated with heat or UV light to create THCV.[12]

Research

Reducing blood sugar

THCV is a new potential treatment against obesity-associated glucose intolerance with pharmacology different from that of CB1 inverse agonists/antagonists.[13] GW Pharmaceuticals is studying plant-derived tetrahydrocannabivarin (as GWP42004) for type 2 diabetes in addition to metformin.[14][better source needed]

Appetite control

THC increases appetite, which is sometimes referred to as "the munchies." THC acts as a CB1 agonist. As a CB1 antagonist, THCV has been shown to reduce appetite in murine models.[15]

Energy and motivation

A 2:1 ratio of naturally derived THCV to THC extract has been demonstrated to show energizing and motivating effects in a double blind placebo clinical study which relied on a self-reported user survey for results.[16][17][better source needed]

Legal status

It is not scheduled by Convention on Psychotropic Substances. [citation needed]

United States

THCV is not scheduled at the federal level so long as it is not derived from cannabis varieties that produce more than .3% THC on a dry weight basis in the United States.[18]

The 2018 United States farm bill legalized the production and sale of THCV if it is derived from hemp compliant with the farm bill.[19][non-primary source needed]

See also

- Cannabinoid

- Cannabis

- Cannabivarin (CBV)

- Cannabidivarin (CBDV)

- Federal Analogue Act

- Hexahydrocannabivarin

- Medical cannabis

- Parahexyl

- Rimonabant (synthetic CB1 antagonist)

- Tetrahydrocannabiorcol (Δ9-THCC, (C1)-Δ9-THC)

- Tetrahydrocannabutol (Δ9-THCB, (C4)-Δ9-THC)

- Tetrahydrocannabihexol (Δ9-THCH, (C6)-Δ9-THC)

- Tetrahydrocannabiphorol (Δ9-THCP, (C7)-Δ9-THC)

References

- ^ Abioye A, Ayodele O, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Akinwekomi A, Sanyaolu A (January 2020). "Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV): a commentary on potential therapeutic benefit for the management of obesity and diabetes". Journal of Cannabis Research. 2 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/s42238-020-0016-7. PMC 7819335. PMID 33526143.

- ^ Adams R, Loewe S, Smith CM, McPhee WD (1942). "Tetrahydrocannabinol Homologs and Analogs with Marihuana Activity. XIII1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 64 (3): 694–697. doi:10.1021/ja01255a061.

- ^ Baker PB, Gough TA, Taylor BJ (1980). "Illicitly imported Cannabis products: some physical and chemical features indicative of their origin". Bulletin on Narcotics. 32 (2): 31–40. PMID 6907024.

- ^ Hillig KW, Mahlberg PG (June 2004). "A chemotaxonomic analysis of cannabinoid variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 91 (6): 966–75. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.6.966. PMID 21653452.

- ^ Brown NK, Harvey DJ (April 1988). "In vivo metabolism of the n-propyl homologues of delta-8- and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the mouse". Biomedical & Environmental Mass Spectrometry. 15 (7): 403–10. doi:10.1002/bms.1200150708. PMID 2839261.

- ^ Pertwee RG (January 2008). "The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442. PMC 2219532. PMID 17828291.

- ^ Pertwee RG, Thomas A, Stevenson LA, Ross RA, Varvel SA, Lichtman AH, et al. (March 2007). "The psychoactive plant cannabinoid, Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, is antagonized by Delta8- and Delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin in mice in vivo". British Journal of Pharmacology. 150 (5): 586–94. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707124. PMC 2189766. PMID 17245367.

- ^ Thomas A, Stevenson LA, Wease KN, Price MR, Baillie G, Ross RA, et al. (December 2005). "Evidence that the plant cannabinoid Delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin is a cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor antagonist". British Journal of Pharmacology. 146 (7): 917–26. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706414. PMC 1751228. PMID 16205722.

- ^ "Tetrahydrocannabivarin". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ McPartland JM, Duncan M, Di Marzo V, Pertwee RG (February 2015). "Are cannabidiol and Δ(9) -tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review". British Journal of Pharmacology. 172 (3): 737–753. doi:10.1111/bph.12944. PMC 4301686. PMID 25257544.

- ^ Jadoon KA (2013-09-13). "Efficacy and Safety of Cannabidiol and Tetrahydrocannabivarin on Glycemic and Lipid Parameters in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel Group Pilot Study". Diabetes Care. 39 (10).

- ^ Walsh KB, McKinney AE, Holmes AE (29 November 2021). "Minor Cannabinoids: Biosynthesis, Molecular Pharmacology and Potential Therapeutic Uses". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 12: 777804. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.777804. PMC 8669157. PMID 34916950.

- ^ Wargent ET, Zaibi MS, Silvestri C, Hislop DC, Stocker CJ, Stott CG, et al. (May 2013). "The cannabinoid Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) ameliorates insulin sensitivity in two mouse models of obesity". Nutrition & Diabetes. 3 (5): e68. doi:10.1038/nutd.2013.9. PMC 3671751. PMID 23712280.

- ^ GW Pharmaceuticals plc (2014-03-17). "GW Pharmaceuticals Provides Update on Cannabinoid Pipeline". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- ^ Riedel G, Fadda P, McKillop-Smith S, Pertwee RG, Platt B, Robinson L (2009). "Synthetic and plant-derived cannabinoid receptor antagonists show hypophagic properties in fasted and non-fasted mice". British Journal of Pharmacology. 156 (7): 1154–1166. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00107.x. PMC 2697695. PMID 19378378.

- ^ Phylos. "Phylos® and People Science® Announce Results of IRB-Backed Controlled Research Study on the Energizing Effects of THCV". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "THCV Efficacy Study_ Abstract and Method [C142-202402-001] (1).pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "§1308.11 Schedule I. section (d) Hallucinogenic substances part (33)". Drug Enforcement Agency. U.S. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 2009-08-27.

- ^ "Summary of H.R. 2 (115th): Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018". GovTrack.

External links

- Erowid Compounds found in Cannabis sativa