COVID Infections Surge While Laboratory Testing Wanes

Contents

-

(Top)

-

1 Biography

-

1.1 Early life

-

1.2 Journalism

-

1.3 Historian

-

1.4 July Revolution (1830)

-

1.5 Deputy and minister (1830–1836)

-

1.6 Prime Minister (1836)

-

1.7 Opposition and Prime Minister again (1837–1840)

-

1.8 Opposition (1840–1848)

-

1.9 February Revolution (1848)

-

1.10 Second Republic

-

1.11 Second Empire

-

1.12 War and fall of the Empire

-

1.13 Government of National Defence (1870–1871)

-

1.14 Chief Executive and end of the fighting

-

1.15 Paris Commune

-

1.16 Making peace

-

1.17 President of the Republic (1871–1873)

-

1.18 Downfall (1873)

-

1.19 Last years

-

-

2 Family and personal life

-

3 Literary career

-

4 Place in history

-

5 Legacy

-

6 Honors

-

7 References

-

8 Further reading

-

9 External links

Adolphe Thiers | |

|---|---|

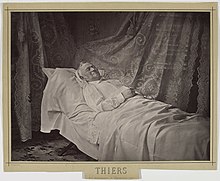

Portrait by Nadar, 1870s | |

| President of France | |

| In office 31 August 1871 – 24 May 1873 | |

| Prime Minister | Jules Dufaure |

| Preceded by | Napoleon III (as Emperor of the French) |

| Succeeded by | Patrice de MacMahon |

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 1 March 1840 – 29 October 1840 | |

| Monarch | Louis Philippe I |

| Preceded by | Jean-de-Dieu Soult |

| Succeeded by | Jean-de-Dieu Soult |

| In office 22 February 1836 – 6 September 1836 | |

| Monarch | Louis Philippe I |

| Preceded by | Victor de Broglie |

| Succeeded by | Louis-Mathieu Molé |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 1 March 1840 – 29 October 1840 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Jean-de-Dieu Soult |

| Succeeded by | François Guizot |

| In office 22 February 1836 – 6 September 1836 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Victor de Broglie |

| Succeeded by | Louis-Mathieu Molé |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers 15 April 1797 Marseille, France |

| Died | 3 September 1877 (aged 80) Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Political party | Party of Resistance (1831–1836) Party of Movement (1836–1848) Party of Order (1848–1852) Third Party (1852–1870) Independent (1870–1873) Moderate Republican (1873–1877) |

| Signature |  |

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers (/tiˈɛər/ tee-AIR; French: [maʁi ʒozɛf lwi adɔlf tjɛʁ]; 15 April 1797 – 3 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian who served as President of France from 1871 to 1873. He was the second elected president and the first of the Third French Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Revolution of 1830, which overthrew King Charles X in favor of the more liberal King Louis Philippe, and the Revolution of 1848, which overthrew the July Monarchy and established the Second French Republic. He served as a prime minister in 1836 and 1840, dedicated the Arc de Triomphe, and arranged the return to France of the remains of Napoleon from Saint-Helena. He was first a supporter, then a vocal opponent of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (who served from 1848 to 1852 as President of the Second Republic and then reigned as Emperor Napoleon III from 1852 to 1871). When Napoleon III seized power, Thiers was arrested and briefly expelled from France. He then returned and became an opponent of the government.

Following the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, which he opposed, Thiers was elected chief executive of the new French government and negotiated the end of the war. When the Paris Commune seized power in March 1871, Thiers gave the orders to the army for its suppression. At the age of seventy-four, he was named president of the Republic by the French National Assembly in August 1871. His chief accomplishment as president was to achieve the departure of German soldiers from most of French territory two years ahead of schedule. Opposed by the monarchists in the French National Assembly and the left wing of the republicans, he resigned on 24 May 1873, and was replaced as president by Patrice de MacMahon. When he died in 1877, his funeral became a major political event; the procession was led by two of the leaders of the republican movement, Victor Hugo and Léon Gambetta, who at the time of his death were his allies against the conservative monarchists.

Thiers was also a notable popular historian. He wrote the first large scale history of the French revolution in 10 volumes, published 1823–1827. Historian Robert Tombs states it was, "A bold political act during the Bourbon Restoration...and it formed part of an intellectual upsurge of liberals against the counter-revolutionary offensive of the Ultra Royalists."[1] He also wrote a twenty-volume history of the Consulate and Empire of Napoleon Bonaparte (Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire). In 1834, he was elected to the Académie Française.

Biography

Early life

Adolphe Thiers was born out of wedlock in Marseille on 15 April 1797, during the rule of the Directorate. His father, Pierre-Louis-Marie Thiers, was a businessman and occasional government official under Napoleon, who led a life of debauchery and was frequently in trouble with the law. On 13 May 1797, his previous wife having died 2 months prior, his father married his mother Marie-Madeleine Amic, with Adolphe thereby becoming a legitimate child, undergoing a baptism by a refractory priest. Nevertheless, the father abandoned Adolphe and his mother not long after. He showed no interest towards Adolphe, and only contacted him in 1825 when he was becoming famous in the Paris journalism scene, to ask him for money. Adolphe responded to the letter saying he feels love and duty only towards his mother, and that only if Pierre can prove he needs the money to stay alive and not for "the most ignoble excesses", would he see what he can do.[2][3]

His paternal grandfather, Louis-Charles Thiers, was an attorney in Aix-en-Provence, who moved to Marseille to become the guardian of the city archives, as well as secretary-general of the city administration, although he lost that post during the French Revolution.[3] Thiers was of Greek ancestry on his maternal grandmother's side; his grandfather Claude Amic left Marseille for Constantinople around 1750 to work for the Seymandi trading post, and while there married a Catholic Greek woman named Marie Lhomaka, whose paternal family originally hailed from Chios and claimed "Frankish" descent. Her father, Antoine Lhomaka, was a wealthy jeweler who supplied the Imperial Harem, and in 1722 accompanied Mehmet Efendi to Paris as a dragoman. Claude Amic later took his family to Marseille in 1770. His mother's uncle, born Ange-Auguste Lhomaka, later converted to Islam, became known under the name "Hadj Messaoud" and moved to the Indies. Adolphe's mother was also a first cousin of the poet André Chenier.[3]

His mother, born in Bouc-Bel-Air, had little money, but Thiers was able to receive a good education thanks to financial aid from an aunt and a godmother. He won admission to a lycée of Marseille through a competitive examination, and then, with the help of his relatives, was able to enter the faculty of law in Aix-en-Provence in November 1815. While studying at the faculty of law he began his lifelong friendship with François Mignet. They both were admitted to the bar in 1818; Thiers made a precarious living as a lawyer for three years. Thiers, who showed a strong interest in literature, won an academic prize of five hundred francs for an essay on the Marquis de Vauvenargues. Nonetheless, he was unhappy with his life in Aix-en-Provence. He wrote to his friend Teulon, "I am without fortune, without status, and without any hope of having either here." He decided to move to Paris and to try to make a career as a writer.[4]

Journalism

In 1821, the 24-year-old Thiers moved to Paris with just 100 francs in his pocket. Thanks to his letters of recommendation, he was able to get a position as a secretary to the prominent philanthropist and social reformer, the Duke of La Rochefoucalt-Liancourt. He stayed only three months with the Duke, whose political views were more conservative than his own, and with whom he could see no rapid avenue for advancement. He was then introduced to Charles-Guillaume Étienne, the editor of the Le Constitutionnel, the most influential political and literary journal in Paris at the time. The newspaper was the leading opposition journal against the royalist government; it had 44,000 subscribers, compared with just 12,800 subscribers for the royalist, or legitimist, press. He offered Etienne an essay on the political figure François Guizot, Thiers' future rival, which was original, polemical and aggressive, and caused a stir in Paris literary and political circles. Etienne commissioned Thiers as a regular contributor. At the same time that Thiers began writing, his friend from the law school in Aix, Mignet, was hired as a writer for another leading opposition journal, the Courier Français, and then worked for a major Paris book publisher. Within four months of his arrival in Paris, Thiers was one of the most-read journalists in the city.[5]

He wrote about politics, art, literature, and history. His literary reputation introduced him into the most influential literary and political salons in Paris. He met Stendhal, the Prussian geographer Alexander von Humboldt, the famed banker Jacques Laffitte, the author and historian Prosper Mérimée, the painter François Gérard; he was the first journalist to write a glowing review for a young new painter, Eugène Delacroix. When a revolution broke out in Spain in 1822, he traveled as far as the Pyrenees to write about it. He soon collected and published a volume of his articles, the first on the Paris Salon of 1822, the second on his trip to the Pyrenees. He was very well paid by Johann Friedrich Cotta, the part-proprietor of the Constitutionnel.[6] Most important for his future career, he was introduced to Talleyrand, the famous diplomat, who became his political guide and mentor. Under the tutelage of Talleyrand, Thiers became an active member of the circle of opponents of the Bourbon regime, which included the financier Lafitte and the Marquis de Lafayette.[5]

Historian

Thiers began his celebrated Histoire de la Révolution française, which founded his literary reputation and boosted his political career. The first two volumes appeared in 1823, the last two (of ten) in 1827. The complete work of ten volumes sold ten thousand sets, an enormous number for the time. It went through four more editions, which earned him 57,000 francs (the equivalent of more than a million 1983 francs). The history of Thiers was particularly popular in liberal circles and among younger Parisians. It praised the principles, leaders and accomplishments of the 1789 Revolution (though not the later Terror), and condemned the monarchy, aristocracy and clergy for their inability to change. The book played a notable role in undermining the legitimacy of the Bourbon regime of Charles X, and bringing about the July Revolution of 1830.[7]

The work was praised by the French authors Chateaubriand, Stendhal and Sainte-Beuve, was translated into English (1838) and Spanish (1889), and won him a seat in the Académie française in 1834.[8] It was less appreciated by British critics, in large part because of his favorable view of the French Revolution and of Napoleon Bonaparte. The British historian Thomas Carlyle, who wrote his own history of the French Revolution, complained that it "was far as possible from meriting its high reputation", though he admitted that Thiers is "a brisk man in his way, and will tell you much if you know nothing". The historian George Saintsbury wrote in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911): "Thiers' historical work is marked by extreme inaccuracy, by prejudice which passes the limits of accidental unfairness, and by an almost complete indifference to the merits as compared with the successes of his heroes."[6]

July Revolution (1830)

A new King, Charles X, had come to the French throne in 1824 with a strong belief in the divine right of kings and the worthlessness of parliamentary government. Thiers had been planning a literary career, but in August 1829, when the King appointed the ultra-royalist, Polignac as his new prime minister, Thiers began to write increasingly fierce attacks on the royal government. In a celebrated article, he wrote that "The King rules, but does not govern," and called for a constitutional monarchy. If the King did not accept it, he proposed simply changing the King, as the English had done in 1688. When the Constitutionel hesitated to publish some of his more energetic attacks on the government, Thiers, with Armand Carrel, Mignet, Stendhal and others, started a new opposition newspaper, the National, whose first issue appeared on 3 January 1830. The government responded by taking the newspaper to court, charging it with attacks on the person of the King and that of the royal family. It was fined three thousand francs. The writer Lamartine left a vivid description of Thiers, with whom he had dinner at this time: "He spoke first; he spoke last; he hardly listened to the replies; but he spoke with an accuracy, with an audacity, with a fecundity of ideas, that excused his volubility of words from his lips. It was his spirit and heart which spoke....There was enough gunpowder in his nature to explode six governments."[9]

In August 1829, Charles X had decided to show his authority over the unruly Chamber of Deputies, and named a fervent royalist, Jules de Polignac as his new prime minister. On 19 March 1830, he raised the temperature, warning that if the deputies put obstacles in his path, he would "find the force to overcome them in my resolution to maintain the public peace, with the full confidence of the French and the love they have also shown toward their King." He also launched an overseas expedition for the conquest of Algeria, which he was certain would increase his popularity at home, and called for new elections, which he was certain he would win. The French flag was hoisted over Algiers on 5 July 1830, and new elections were held from 13 to 19 July. The elections were a disaster for the King; the opposition won 270 seats, against 145 supporters of the King. The opponents were, for the most part, not republicans; they simply wanted a constitutional monarchy. The King responded, however, on 25 July with new decrees dissolving the Chamber of Deputies, changing the election laws, and putting restrictions on the press. The King, confident in his popularity, neglected to put the army on alert or to bring in soldiers to maintain order.

Thiers reacted immediately and forcefully. On the front page of his newspaper, the National, he declared: "The legal regime is over; that of force has begun; in the situation in which we are placed, obedience has ceased to be an obligation." He persuaded the editors of the other major liberal newspapers to publish a joint declaration of opposition, which was published on the morning of 27 July. Later that morning, the prefect of police arrived at the National with orders to put the newspaper out of business. He brought workers who seized key mechanical parts of the printing presses, and locked the building. As soon as the prefect left, the same workers who had locked the building and disabled the presses re-opened it and put the presses back into service. Anti-royalist demonstrations broke out in many parts of Paris. Thiers and his allies briefly left the city to avoid arrest, but soon came back. Thiers noticed that the anti-royalist demonstrators had attacked shops which had signs showing that they were patronized by Charles X, but not those which advertised they were patronized by the King's cousin, Louis-Philippe, the Duke of Orleans, whose family had been sympathetic to the French Revolution. Without consulting with Louis-Philippe, whom he had never met, Thiers immediately had posters printed and put up around Paris declaring that the Duke of Orleans was a friend of the people, and he should take the crown.[10]

With the painter Ary Scheffer, a friend of Louis-Philippe, he rode on horseback immediately to the Duke's residence in Neuilly, but found that the Duke had left and was in hiding at another chateau in Raincy. Thiers talked instead to the Duke's wife, Marie-Amélie, and his sister, Madame Adélaïde. Thiers explained that they wanted a representative monarchy and a new dynasty, and that everyone knew that Louis-Philippe was not ambitious and had not sought the crown for himself. Madame Adelaide agreed to take the proposition to the Duke. The Duke returned to Neuilly at ten in the evening and learned what had happened from his wife. He put on a tricolor ribbon, the symbol of the opposition, and rode to the Palais-Royal, where Thiers, the Marquis de Lafayette and Jacques Laffitte were waiting. Together, they persuaded him to take the throne and discussed how it would be done. That afternoon, they rode to the Hotel de Ville. Louis-Philippe, wrapped in a tricolor flag, was presented to the huge and cheering crowd in front of the Hotel de Ville by LaFayette. King Charles X withdrew his proposed new government and offered to negotiate, but it was too late. He and his son departed the Chateau of Saint-Cloud and left France for exile in England.[11]

Deputy and minister (1830–1836)

When the new government was formed, Thiers, with no government experience, was given a lesser position, that of undersecretary of state for Finance, under Laffitte, but was also awarded the Legion of Honor and the position of state counselor, which had a substantial salary. He ranked as one of the Radical supporters of the new dynasty, in opposition to the party of which his rival François Guizot was the chief literary man, and Guizot's patron, the duc de Broglie, the main pillar.[6] To have real influence and independence, Thiers knew that he needed a seat in the chamber of deputies, not just a government position. But to be eligible to run, he needed to own property important enough that he paid taxes of at least one thousand francs a year. His intimate friend, Madame Dosne, spoke to her husband, a wealthy businessman. Dosne arranged a loan of one hundred thousand francs to Thiers so that he could buy a lot and build a house in a new real estate development at Place Saint-George. In return, Dosne received the position of Receiver-General in Brest. A seat for Aix-en-Provence in the chamber of deputies was vacant. Now that he was eligible, Thiers ran and was elected on 21 October 1830. Ten years after his arrival in Paris, he began his political career.

He gave his first speech in the Chamber of Deputies, on the financial situation of the country, a month after his election. He had no experience as an orator; because of his small stature, his head barely appeared over the podium, and he spoke with a strong Provençal accent, which made the Parisians smile. The long, carefully prepared speech was greeted at the end with silence, though the content was approved. Thiers worked very hard to improve his speaking style, and eventually became a very effective orator.

The new government faced many difficulties. It gradually divided into two informal parties: the so-called Party of Movement, to which Thiers belonged, which wanted the maximum number of reforms as soon as possible; and the conservative Party of Order, who, once the new government was installed, wanted no further turbulence. Louis-Philippe made Jacques Laffitte, an advocate of rapid reform, his chief minister, in the anticipation that he would soon fail and would have to be replaced, which was exactly the result. After four and half months of turmoil, The King dismissed Laffitte and replaced him with a supporter of Order, Casimir Périer. Thiers was out of the government, and left only with his position as Deputy, which had no salary.[12]

The funeral of an anti-government figure, General Lamarque, in June 1832, later immortalized by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables, turned into the June Rebellion against the monarchy, with barricades raised in the Saint-Merri district. After it was suppressed, Thiers was brought back into the government as Minister of the Interior. He helped put down a Quixotic armed rebellion of the Legitimists under the Duchess de Berry who wanted to put the Bourbon dynasty back on the throne. She was hiding in a secret room behind a fireplace in Nantes, and was captured when the police looking for her, wishing to stay warm, started a fire, forcing her to surrender. In 1833 he declared he did not want to be the Joseph Fouché of the regime (the name of Napoleon's chief of the secret police) and became Minister of Trade and Public Works. As a Deputy, he opposed the proposal for an income tax on the rich, arguing that it was a Jacobin idea of the French Revolution. This position won him the support of the growing French business class.

In 1833, he was nominated for an open seat in the Académie française, based on his ten-volume history of the French Revolution, and other books he had written on the law and public finance, and the 1830 monarchy, and the Congress of Verona. He was elected on the first ballot, with twenty-five votes; at age thirty-six, he was the second-youngest member elected in the 19th century. In July 1833, Thiers dedicated a new Paris landmark, the column in Place Vendôme. After 1833, his career was bolstered by his marriage to the daughter of his intimate friend, Madame Dosne, which allowed him to pay off his one hundred thousand franc loan from her father, finally giving him financial security. It also caused problems for him, because the aristocracy of Paris refused to receive her, since she was not one of them.[13]

He returned to the Interior Ministry in 1834–36, and had to deal with discontent of the growing working class in France's large cities. A workers' revolt in Lyon on 9 April 1834, caused by a reduction of salaries, led to riots and the death of 170 workers and 130 police and soldiers. Shortly afterwards, on 13 April, barricades went up in the Marais district in Paris. The army was summoned and launched forty thousand soldiers against the barricades. On rue Transnonain, a sergeant was wounded by a gunshot from a building. The soldiers attacked the building, killing the twelve inhabitants. Thiers was thereafter blamed by republicans and socialists for the "Massacre of rue Transnonain."[14]

Thiers also played an active role in the decoration of Paris; he cleared the space in front of the eastern colonnade of the Louvre, so visitors could have a clear view, and ordered the restoration of the Salon of Apollo, which became the setting for the famous Paris salon art exhibitions.[citation needed] He commissioned the bas-reliefs for the Arc-de-Triomphe, and selected Eugène Delacroix to paint murals for the library of the French Senate and frescoes on the walls of the church of Saint-Sulpice, despite the opposition of Louis-Philippe, who disliked Delacroix's painting.[15]

Prime Minister (1836)

In January 1836, the unpopular government of the Duke of Broglie lost its majority in the Chamber of Deputies, and the King needed a new Prime Minister. As he had done in 1830, he chose a man he was certain would soon fail; Adolphe Thiers. On the subject of Thiers, Louis-Philippe told Victor Hugo, "He (Thiers) has spirit, but he is spoiled by the spirit of a parvenu; he has shown himself to be insatiable." Louis Philippe cited what he said was Talleyrand's view of Thiers: "You will never make anything of Thiers, but nonetheless he will be an excellent instrument. But he is one of those men whom you can make use of only if you give them satisfaction; but he is never satisfied. The misfortune, for you and for him, is that you cannot make him a cardinal."[16]

Thiers accepted the position, and chose a government, keeping for himself the position of Foreign Minister. He told the Chamber of Deputies, "Our country is in the middle of the greatest perils, and we must fight the disorder with all of our force. To save a revolution, we must preserve it from its own excesses. Whether these excesses are produced on the streets or in the abusive use of institutions, I will contribute, through force and by the laws, to put them down."[17] He was given the support of the Deputies by a vote of 251 to 99. His new government proposed the construction of the first railroad in France, from Paris to Saint-Germain (though Thiers privately described it as "A toy for the Parisians") and suppressed the national lottery on the grounds of morality.

Violent opposition to Louis-Philippe increased. A gunman named Alibaud attempted to shoot Louis-Philippe, who was saved by the armored walls of his carriage. The police linked Alibaud to a secret revolutionary group called "Les Familles", by Armand Barbès and Louis Blanqui. Both were arrested and imprisoned, but later released, and went on to much more ambitious revolutionary projects. Because of the new threat of terrorist attacks, Louis-Philippe decided not to inaugurate the newly completed Arc de Triomphe, begun by Napoleon. Thiers dedicated the monument on 29 July 1836. The relationship between Thiers and Louis-Philippe became more and more strained. The King blocked many of Thiers' diplomatic initiatives, and conducted his own foreign policy. Thiers suggested to the King that France should follow the British model, and allow the Prime Minister to conduct all of the diplomatic and military affairs. Louis-Philippe refused, insisting that France was not England and he was the chief diplomat and head of the army. Thiers felt he had no alternative but to resign as prime minister, which he did on 29 August 1836. His place was taken by a conservative royalist, Louis-Mathieu Molé.[18]

Opposition and Prime Minister again (1837–1840)

Out of office, he traveled in Italy. He went first to Rome, where his friend Ingres, the Director of the Villa Medici, gave him a tour of the monuments, then to Florence, where he had the idea of writing a history of that city. He rented a villa at Lake Como and began collecting documents for his research. He went to Italy two more times in 1837, renting the Villa di Castello and going through the archives. In the meanwhile, Louis-Philippe was increasingly unpopular. He survived three more assassination attempts, and new elections on 4 November showed gains for the center left, and losses for the center right. Thiers returned to the Deputies and in January 1839 delivered of series of speeches denouncing the government of the King, led by Molé. The government was assaulted from all sides, from the extreme right, extreme left, and center. Molé was forced to resign and call for new elections, which were held on 2 March 1839. The opposition won the elections, but because of their diverse views struggled to form a majority. For three months France was without a government. The most radical French revolutionaries, Barbés and Blanqui, saw this as the moment to launch a violent revolution. They had formed a secret organization, the Societé des Saisons, with about fifteen thousand members. On Sunday, 12 March 1839, when the center of Paris was deserted, they formed armed columns, and successfully seized the Palais de Justice and the Hôtel de Ville. From the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, Barbés read a decree announcing the creation of a revolutionary government. But the army reacted immediately, and by the evening the revolution was reduced to a few barricades in the Faubourg Saint-Denis. Barbés and Blanqui were arrested and sentenced to confinement for life in the prison on Mont-Saint-Michel.

Thiers saw his moment and ran for President of the Chamber, but was narrowly defeated by a vote of 213–206. Louis-Philippe, who by this time detested Thiers, said with satisfaction that Thiers "had the effect of a melon striking a stone". but Thiers still had a strong following in the chamber. In offering him the position of head of the government, Louis-Philippe told Thiers, "Here I am obliged to submit to you, and accept my dishonor. You have been forced upon me. You will put my children out onto the streets. But finally I am a constitutional king, and I have no choice but to go through with it."[19]

As President of the council or Prime Minister, Thiers kept for himself the title of Foreign Minister. His most notable accomplishment was to obtain from Britain the return of Napoleon's ashes from Saint Helena. The idea was particularly pleasing to Thiers, because he had just begun writing a history of the Consulate and Empire, in twenty volumes. Rather than making the request public, he wrote to a personal English friend, Lord Clarendon, who was a member of the British government, saying: "to keep a cadaver as a prisoner is not worthy of you, nor is it possible on the part of a government such as yours. The restitution of these remains is the final act of putting behind us the fifty years that have passed, and will be the seal placed on our reconciliation, and our close alliance." The British prime minister, Lord Palmerston, considered and accepted the request. The transfer was opposed by some in the French parliament, including Lamartine, who feared that it would stir republican sentiment in France, but it was welcomed by the population. A warship was dispatched to Saint Helena, and Thiers worked on the details of the design of the tomb and the plan of the parade that would carry it to the tomb, constructed within Les Invalides. The return of the ashes was a huge success, attracting enormous crowds in Paris. But by the time it took place Thiers was no longer in the government.[20]

More unexpected news arrived on 5 August, while the remains of Napoleon were still en route from St. Helena to Paris. Louis-Napoleon, the nephew of the Emperor, had landed at Boulogne with a small force of soldiers, and had tried to spark an uprising by the army to overthrow Louis-Philippe. The soldiers in Boulogne refused to change sides; Louis-Napoleon was captured, taken to the Conciergerie in Paris, and put on trial. He was sentenced to life in prison, and sent to serve his sentence to the fortress of Ham.

The year 1840 also brought a political crisis between France, Russia and Britain because of France's support for the ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, a long-time ally. (In 1829 he had donated the Luxor obelisk, now standing in the Place de la Concorde.) Lord Palmerston was convinced that the French would not fight, and sent a fleet to bombard Beirut and threaten Egypt. The French cabinet was divided, fearing that France was not ready for war; the French army was already engaged in the long, expensive military conquest of Algeria. The King made it clear to Thiers that he wanted peace. Thiers offered to resign, but the King refused his resignation, arguing that he wanted the British to believe that France would fight. When Thiers drafted a note to Britain warning that a British ultimatum to Egypt would upset the global balance of power, and he ordered construction of a new ring of fortresses around Paris. Palmerston did not attack Egypt, and crisis ended. The fortifications begun by Thiers during crisis were eventually finished, and became known as the Thiers wall, which later became (and remain today) the city limits of Paris.[21]

After the end of the crisis, tensions remained between the King and Thiers, who drafted the King's annual address to the Chamber of Deputies, adding the line, "France is strongly attached to peace, but it will not purchase peace at a price unworthy of the nation and its King," and would not sacrifice the "sacred independence and national honor which the French Revolution had put into his hands." Louis-Philippe removed this line from the speech, considering it too provocative to other European rulers. Thiers promptly offered his resignation, and this time it was accepted. A month later, he rose in Parliament to denounce the King's foreign policy, declaring that France had lost its influence in the Middle East, and had a duty to defend Egypt against Britain, and Turkey against Russia.

Opposition (1840–1848)

Once outside of the government, he devoted much of his time to writing Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, the first volume of which appeared in 1845.[6] The book was a huge success, selling twenty thousand copies in a few weeks. The book was criticized by Chateaubriand, who called it "an odious advertisement for Bonaparte, edited in the style of a newspaper" It had the unplanned effect of raising even further the prestige of Napoleon's nephew and Thiers' future enemy, Louis-Napoleon.[22]

In December 1840, Thiers helped secure the election of Victor Hugo to the Académie Française, despite the opposition of the more conservative members. Hugo was accepted only on the fifth ballot, by a single vote. When elected, Hugo sent a copy of his new poem about Napoleon to Thiers, declaring to Thiers that Thiers was "a man I honor and love; your spirit is one of those that seduces my own. One feels that before you entered the world of great affairs, you traversed that of great ideas. With my full sympathy, high estime and vivid admiration."[23] From 1840 through 1844, Thiers traveled around Europe, crisscrossing Holland, Germany, Switzerland and Spain and visiting he battlefields where Napoleon fought and meeting people who had witnessed them. In the meanwhile, his chief political rival, Guizot, the leader of the right wing in the Deputies, headed the government. He called new elections in July 1846, which Guizot's party narrowly won, with 266 seats of 449. However, in an ominous sign, ten of the twelve deputies from Paris opposed the government. As the King's unpopularity grew, he suffered also a personal tragedy with great political implications; his son, the heir to the throne, was killed in an accident. His grandson, the new heir, was only a child.

Opposition to the King continued to grow; he was the target of two more assassination attempts in 1846. In the spring of 1846, Louis-Napoleon, disguised as a stonemason, escaped from the prison at Ham and fled to England, where he waited for an opportunity to make a grand return to France. Thiers, the leader of the center-left deputies, began to take a more active part in the Chamber of Deputies. He told a colleague, "The King is easily frightened. He will only call on me when he is in danger. I will only take the ministry if I can be the master of it."[22] A proposal to make a larger number of citizens eligible to vote was rejected by Guizot and his government: Guizot declared to the Chamber, "the day will not come for universal suffrage."[24]

February Revolution (1848)

The last parliamentary session of the constitutional monarchy began on 28 December 1847 with the announcement of a military success; the resistance to French rule in Algeria had been defeated. But immediately, opposition to the government grew. Since political meetings were forbidden, the left opposition began to organize banquets, large dinners in public places which were really opposition meetings. Thiers declared to the Chamber, "Our country is marching with giant steps toward a catastrophe. There will be a civil war, a revision of the Charter, and perhaps a change of personnel at the highest level. If Napoleon II were alive, he would take the place of the present King."[25]

The left opposition declared that they would hold an enormous banquet on the Place de la Madeleine on 22 February. Fearing trouble, Guizot declared the banquet illegal, and ammunition was given to the army garrison, and they prepared for trouble. Thiers, believing that the government was too strong to allow an uprising, advised caution and said he would not attend the banquet.[24] The army commander, Marshal Bugeaud, put squadrons of dragoons on the streets. The day began peacefully, but by midday groups of demonstrators were raising barricades on the Champs-Élysées and hurling rocks at soldiers in front of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at the corner of Boulevard des Capucines and rue Cambon. The volunteer members of the Garde Nationale were summoned to support the army, but few turned out. Thiers toured the streets on foot, and was recognized and cheered by many of the demonstrators. The demonstrations resumed on 23 February, under a freezing rain. The King remained calm, telling his sister, "The Parisians never make a Revolution in the winter, and they won't overthrow the Monarchy for a banquet." As the day advanced, the demonstrators raised more barricades and confronted the army. The leaders of many of the National Guard units informed the Prefect of police that they wanted reform and would not support the army against the population. A crowd of 600–800 National Guards threatened to storm the National Assembly building. Thiers addressed them, reminding them that the assembly was democratically elected. The guardsmen stopped their assault, and gave the parliament members a petition demanding reforms.

Within the Tuileries, the King was uncertain what to do. His prime minister, Guizot, advised him to form a new government under Molé, but Molé declined and suggested Thiers have the job. "The house is burning," Molé told the King. "You have to call on those who can put out the fire."[26] The King reluctantly agreed, and sent for Thiers, but another event that evening changed the course of the Revolution; a unit of the army fired without orders on demonstrators outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Boulevard des Capucines, killing sixteen and wounding dozens.

Early in the morning of 24 February, Thiers arrived at the Tuileries and met with the King, who was in despair. He met also with Marshal Bugeaud, and learned that the army had only sixteen thousand men available; they were short of ammunition and exhausted. During the night, more barricades had appeared all over Paris. Thiers proposed withdrawing the army to Saint-Cloud, gathering his forces, and marching back into Paris with a full army (the strategy he followed in 1871 during the Paris Commune), but Marshal Bugeaud wanted to attack the barricades immediately; he told the King that it would cost twenty thousand lives; the King told Bugeaud that the price was too high, and called off the attack. The army columns began to disintegrate, as the soldiers joined the demonstrators. Thiers urged the King to flee to Saint-Cloud, but the King insisted on having his regular breakfast at 10:30 a.m., and then put on the uniform of a Lieutenant General to review the four thousand regular soldiers and two legions of National Guards gathered in the courtyard of the Tuileries. As he rode by, the regular soldiers cheered the King, but the National Guardsmen called out "Down the Ministers! Down with the system!" and shook their weapons at the King. The King abruptly turned around rode back to Palace, where he sat in an armchair, head in his hands. "Everything is lost," he said to Thiers, "I am overwhelmed." Thiers responded coldly, "I've known that for a long time." His family urged him to remain and fight. The King turned to his marshals and generals and to Thiers and asked if there was any alternative, but they were silent. The King slowly wrote out and signed his act of abdication, changed from his uniform into civilian clothes, and left through the gardens of the Tuileries. A carriage took him out of Paris to Saint-Cloud, and soon afterwards he crossed the Channel to exile in England.[27]

Second Republic

Once the King was gone, Thiers and the other Deputies moved quickly to the Chamber of Deputies to decide what to do next. They had not been there long before an immense crowd invaded the Chamber, shouting "Long live the Republic!" Thiers fled on foot, and made his way back to his house. A new government was quickly formed by the republicans Lamartine and Ledru-Rollin, but Thiers had no part in it. The new interim government quickly decreed the freedom of the press and freedom of assembly, and called for new parliamentary elections, in which all men over the age of 21, who had been resident in their home for six months, could vote, raising the number of eligible voters from 200,000 to nine million. The Chamber was expanded to a National Assembly with nine hundred members. New elections were held; Thiers ran as a candidate in Marseille, and, for the first and only time in his career, was defeated. However, on 15 May, the more radical socialists staged effort to seize the government; they invaded the chamber and proclaimed a new government. This time, the Republican National Guard responded quickly to defend the government, recapturing the hall and the government. The socialist deputies who had taken part were expelled from the Assembly, leaving open seats. New elections for the open seats were held on 4 June, and Thiers was elected in four departments; Seine, Gironde, Orne, and Seine-Inferieure. He chose to be deputy for Seine-Inferieure.

At the same time, a familiar name reappeared in French politics; Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, resident in London, was elected to a seat in Paris by 80,000 votes, and also to seats in three other departments. The more radical republican deputies contested his election; Louis-Napoleon promptly withdrew his candidacy and remained in London, waiting for a more opportune moment. Thiers had been considered a leftist republican in the government of Louis-Philippe, but after the political earthquake of the 1848 revolution and the influx of new deputies, he appeared relatively conservative. While he was out of the Assembly, he published an essay in defense of capitalism and private property which won him the support of the French business community and middle class. Thiers took his seat as the head of the Finance Committee, and leader of the conservative republicans. In the tense and sometimes violent political climate, he took up the habit of always carrying a loaded pistol.[28]

In September, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte returned to Paris and took part in the legislative elections. Though he stayed in London, was a Swiss citizen, and did not campaign, he was overwhelmingly elected in five departments. He took a residence on Place Vendôme. The first appearance of Louis-Napoleon at the Assembly, his Germanic accent and awkward speaking style, persuaded Thiers and other Deputies that he was minus habens; an imbecile. This was also the view of Ledru-Rollin and the socialist deputies. The new Assembly voted to hold elections for a new President of the Republic, the first in which all Frenchmen with residences could vote. Elections were set for 10 December 1848. Thiers considered running, but told Falloux, another Deputy: "If I lost it would be a grave setback for the ideas of order; if I won, I would be obliged to embrace the ideas of the Republic, and, in truth, I am too honest a lad to marry such a bad woman."[29] Instead, he made the major mistake of his political career; he decided to support Louis-Napoleon, certain that he could control him. He believed that Louis-Napoleon's term would be a failure, which would open the way for Thiers to run in 1852. On the eve of the vote, Thiers hosted Louis-Napoleon at his home for dinner. In the December 1848 elections, the moderate republican Lamartine received just 18,000 votes; the socialist Ledru-Rollin received 371,000, and the conservative General Cavaignac received 1,448,000 votes. Louis-Napoleon received 5,345,000 votes, or three-quarters of the votes cast.

On 11 December, shortly after the elections, Louis-Napoleon invited Thiers to his home for dinner, and they discussed the future government. Louis-Napoleon offered the position of President of the Council of Ministers to Thiers, but Thiers refused. He wanted to retain his independence as a deputy. He and his wife dined frequently with Louis-Napoleon in the new presidential residence, the Élysée Palace. Under the new Constitution, new elections for the National Assembly were held on 13 May 1849. The new Assembly had 750 members, of whom 250 were republicans, including 180 radicals or socialists. There were 500 monarchists, divided about equally between Legitimists, who wanted a constitutional monarchy under a Bourbon king, and the Orleanists, who wanted a king from the family of Louis-Philippe. The socialists were impatient with the slow pace of change; led by Ledru-Rollin, they staged an uprising in Paris, which was quickly suppressed by the army. Ledru-Rollin fled to London. In 1849 a cholera epidemic struck Paris; among the victims was Thiers' father-in-law. Thiers and his wife inherited a substantial fortune.[28]

In a speech in the Assembly in 1849 Thiers explained his political philosophy: "Unlimited liberty leads to a barbaric society, where the strong oppress the others, and only the strongest have unlimited liberty... The liberty of one person stops at the liberty of other. Laws are born from this principle, and a civilized society. No one person has it in his power to instantly achieve the happiness of nations."[30] On social issues he became more conservative; formerly a critic of the role of the church in education, he supported the Falloux Laws of 1850, which established a mixture of both Catholic and public schools, and for the first time required that each Commune of over five hundred persons have a school for girls.

The most conservative measure he proposed was a change in the electoral laws, which required that voters have lived in their residences for at least three years, and required a certain minimum income. He declared to the Assembly: "Our goal is not to exclude the poor from voting, but to exclude the vile multitude, those who have handed over the liberty of so many republics to so many tyrants over the years." The law was approved, removing one-third of the voters in France from the voting lists. Thiers did not foresee that Louis-Napoleon, elected by universal suffrage, would later use this law as a weapon against the Assembly to reinforce his own rule. When a friend of Louis-Napoleon asked him if he wasn't afraid of losing power without universal suffrage, he replied, "Not at all. When the Assembly is hanging over the precipice, I will cut the cord."[31]

As 1852 approached, Thiers looked forward to the end of the term of Louis-Napoleon; under the Constitution, he could not run again. Thiers began looking for other candidates to replace Louis-Napoleon, perhaps with the Duke of Joinville, from the Orleans family. Thiers and the other conservative leaders of the Assembly also rebelled against the high cost of Louis-Napoleon's household; he requested 175 new staff for the Palace, and asked funding for an additional twenty grand dinners and twelve grand balls a year. Thiers and the Assembly rejected his request. Louis-Napoleon also sought an amendment to the Constitution to allow him to run for a second term; the vote was held on 21 July 1851. Louis-Napoleon's proposal won a majority of the Assembly, but not the two-thirds required by the Constitution.

Blocked by the National Assembly, Louis-Napoleon decided to take a different route. In public he blamed Thiers and the Assembly for restricting the right to vote and for refusing to alter the Constitution for a second term, and secretly brought loyal army forces to Paris. Early in the morning of 2 December 1851, in what became known as the December 1851 coup d'état, the army took up positions in key positions in Paris, and at six a.m. the commissioner of police, Hubault, appeared at his residence at Place Saint-Georges and placed him under arrest. "But don't you know the law?" Thiers protested. "Do you know that you're violating the Constitution?" Hubault replied, "I do not have the mission of discussing this with you, and moreover you have more knowledge than me." A carriage took Thiers to Mazas Prison. From his jail cell he could hear the sound of gunfire as the soldiers loyal to Louis-Napoleon secured the city. On 9 December, he was transported to the German border and sent into exile.

Second Empire

Thiers went to Brussels, where he learned that Louis-Napoleon had organized a national referendum on his rule; more than seven million voters approved the coup, while 646,000 disapproved it. Only in Paris was the coup unpopular; only 133,000 of 300,000 voters approved the coup. Special tribunals were set up to judge the republican opponents of the new regime; 5,000 were confined to house arrest, almost ten thousand were deported to prison camps in Algeria, and 240 were sent to camps in Guyana. 71 Republican deputies of the Assembly were, like Thiers, expelled from France. Thiers was bored in Brussels, so he moved to London, where his wife and mother-in-law joined him. He was received by the Duke of Wellington and Benjamin Disraeli, but as a native of Provence, he could not endure the British climate and soon departed for long travels in Germany and Italy. In the summer of 1852, Louis-Napoleon decided that he was no longer a threat, and on 20 August 1852 he was allowed to return to Paris. He stayed out of politics. He resumed his friendship with the painter Delacroix and with the sculptor François Rude, whom he had commissioned to make sculptural decoration for the Arc-de-Triomphe. For the next ten years, he devoted his attention to writing his history of the Consulate and Empire, publishing two volumes a year. The 19th and final 20th volume were published in 1862. The series was an immense public success; he sold fifty thousand subscriptions to the entire series, for a total of a million volumes. In addition to the advance of 500,000 francs he received for writing the work, he received author's royalties, which added to his already substantial fortune from mining stock and the inheritance from his father-in-law.[32]

In 1863, the now Emperor Napoleon III began to loosen some of the restrictions on political opposition. Thiers was encouraged to re-enter political life by his friends, and by a new acquaintance, the Prussian ambassador to Paris, Otto von Bismarck. Thiers decided to run for election to the Assembly. On 31 May 1863, at the age of sixty-six, he was elected as a deputy for Paris. He returned to the Assembly on 6 November 1863 and took his seat, but found that under Napoleon III the protocol had changed. Instead of speaking from the tribune, members were only allowed to speak from their seats. Thiers was uncomfortable with this way of speaking, and his first few speeches were failures, but he soon mastered the form. On 11 January 1864 he delivered a blistering attack on Napoleon's government, and listed the "necessary liberties" he said were lacking in France: "Security of the citizen against violence from individuals or from the arbitrary use of power; liberty, but not impunity, for the press; free elections; freedom of the people's representatives; and public opinion expressed by the majority guiding the steps of the government. These are the liberties that the people are asking for today; tomorrow, in a tone very different, they may be demanding them." The speech made him again a leading figure of the opposition; he was cheered by a crowd outside his house when he returned home.[33]

In the months that followed, Thiers criticized the Emperor's costly and doomed expedition to conquer Mexico. He also condemned the Emperor's principle of nationalities, as applied in Italy, of supporting the unification into one country of small states whose populations spoke a common language. "This principle will lead," Thiers said, "one day or the other, to a policy of race which will generate future wars.[citation needed] On 3 May 1866, when war seemed likely between Prussia and Austria over the Prussian annexation of Holstein, Thiers told the assembly: "If Prussia is successful, we will see the creation of a new German Empire; the Empire of Charles V which once resided in Vienna, will now reside in Berlin; an Empire which will press against our borders..." After the crushing defeat of Austria by Prussia at the Battle of Sadowa, Thiers declared, "It was France which was defeated at Sadowa." On 14 March 1867, he told the Assembly: "France has no more allies in Europe. Austria is defeated, Italy is looking for adventure, England wants to avoid the Continent, Russia is occupied with its own interests, and as far as Spain is concerned, never have the Pyrenees been so high. We have to secure an alliance with England, and rally the small states. This is a modest policy but confirms with good sense. We cannot afford to commit another error."[34]

On economic policy, he was relentlessly conservative; he called for protectionism to defend French industry, and condemned the high cost of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann's rebuilding of Paris, which had reached 461 million francs. Under pressure from the Assembly, Napoleon III was forced to dismiss Haussmann. Thiers faced opposition from both the left and right. In the elections of 1869, he was defeated in the election for his seat in Marseille by the republican Gambetta, but, against a candidate backed by Napoleon III, he retained his seat in Paris. A national referendum on Napoleon's policies on 8 May 1870, confirmed the Emperor's popularity in the provinces of France by a vote of 7,386,000 yes, 1,560,000 no, and 1,894,000 abstentions. It also confirmed his unpopularity in Paris, which voted 184,000 no and 138,000 yes. [35]

War and fall of the Empire

The new Chancellor of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck, saw France as the main obstacle to German unification under Prussia. He adroitly managed a diplomatic crisis over the Spanish throne to bring about a war with France, which he was confident Prussia would win. The press in Paris began clamoring for war, and Napoleon's marshals assured him that France would win. Bismarck privately told his friends that his declaration to the French on the crisis "had the effect of a red flag on a bull." Thiers knew Bismarck well and saw clearly what he was doing. The prime minister, Émile Ollivier, spoke to the Assembly on 15 July, saying that France had done all it could to avoid war, but now it was inevitable, and France was well prepared and would win.

Thiers rose to speak and declared: "Do you really mean to say that, for a question of form, you have decided to release torrents of blood?" He demanded proof that Prussia had really insulted France. The members of the right wing parties jeered and hooted Thiers, and one Deputy called out, "you are the anti-patriotic trumpet of disaster!" Thiers responded, "I find this war extremely imprudent. More than anyone else I want to repair the results of Sadowa, but I find the occasion extremely badly chosen." The right wing of the Assembly erupted with insults, calling him a traitor, a fool and worthless old man. After the session, he was insulted in the streets and a crowd gathered to throw stones at his house. The Assembly, confident of success, ignored Thiers and voted on 19 July to declare war. That evening Thiers told a friend, the Deputy Buffet, "I know the state of the military in France and that in Germany. We're lost."[36]

As the Franco-Prussian War progressed, Thiers' warnings proved correct. Due largely to the country's inefficient railroads and a defective plan, the French Army was only able to mobilize 264,000 men in the first weeks of the war, as opposed to 450,000 Germans. The French army, led by Napoleon III in person, had a superb cavalry, but the Germans had superior artillery and leadership. On 1 September the French army was trapped and surrounded at Sedan. To avoid a slaughter, the Emperor surrendered the army on 2 September, and was taken prisoner with his army.

Government of National Defence (1870–1871)

The news of the disaster reached Paris on 2 September, and was confirmed the next day. Two hundred twenty Deputies of the Assembly gathered on the 4th and, following Thiers' formula, declared that, "due to circumstances", there was a vacancy of power. At the same time, a group of republican deputies, including Léon Gambetta and headed by General Trochu, met at the Hôtel de Ville and formed a provisional government, called the Government of National Defense, which was determined to continue the war. Thiers told the monarchist deputies, "In the presence of the enemy, who will soon be outside Paris, we have just one thing to do; to retire from here with dignity." He closed the session of the Assembly and offered his services to the new republican government.[37]

On 9 September, Jules Favre the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the new government, asked Thiers to go to London to persuade the British to join an alliance with France against Prussia. Thiers, though he was seventy-four years old, agreed to accept the mission, and offered to visit other capitals as well. He traveled by train and boat to Calais and London, where he met with Lord Granville, the British Foreign Minister, and William Gladstone, the Prime Minister. Thiers was so exhausted by the voyage that he fell asleep when Gladstone was speaking. Gladstone was sympathetic, but explained that Britain would remain neutral. He did offer to arrange a meeting between Favre and the Germans to learn what the terms would be for ending the war. The meeting between Bismarck and Favre took place 18–20 September at the Rothschild estate at Ferrières, near Paris. Bismarck explained to Favre that, to end the war, France would need to surrender Alsace, part of Lorraine, several border fortresses, and a large sum of money. Favre rejected the proposal, declaring, "not an inch of our territory, not a stone of our fortresses." With the negotiations at an end, the German army moved swiftly to surround Paris.

Thiers continued his long voyage in search of allies. He travelled to Vienna and met with the Chancellor of Austria, then to Saint Petersburg, where he met with the Czar and the Russian prime minister, but he received no support. He returned to Vienna to meet Emperor Franz Joseph, and went to Florence to meet King Victor Emmanuel II, and was kindly received, but received no offers of military support. Thiers returned to France, convinced that government would have to negotiate an end to the war. On his return to France, he headed to Paris. Chancellor Bismarck arranged for Thiers to pass through the German lines to meet with the French government within the city, which by this time was completely surrounded by German troops. When Thiers arrived in Paris on 31 October 1870, the situation was extremely tense. Félix Pyat, a radical socialist and a future leader of the Paris Commune, organized demonstrations against Thiers, whom he accused of threatening to sell France to the Germans, and threatened to have him hung. Favre urged Thiers to go to Versailles and negotiate with Bismarck. Thiers crossed the lines again and met Bismarck. The negotiations continued for four days; Bismarck demanded only Alsace and a large payment. Thiers returned to Paris and urged Favre and the Government to accept the offer and end the war, but General Trochu and Favre were adamant that Paris could hold out and that France was still strong enough to win the war.[38]

The French forces inside Paris made unsuccessful efforts to break the German siege, while the German army advanced through the Loire Valley, and the Government of National Defense, along with Thiers, was forced to move to Bordeaux. On 6 February 1871, Gambetta resigned from the government. and new elections were called for 8 February. The government accepted a temporary armistice beginning on 17 February. On the same day, in a grand ceremony in the Palace of Versailles, the Germans proclaimed William I the first Emperor of the new German Empire. While Paris still wanted to resist, most of France wanted an end to the war as soon as possible. Thiers was a candidate in the elections, and won in twenty-six different departments, with a total of two million votes. He chose to represent a seat in Paris. The majority of the two hundred newly elected deputies favored a constitutional monarchy, though it is also included a substantial group of republicans, including Victor Hugo. At the first session, Jules Grévy, a republican sympathetic to Thiers, was elected president of the assembly, with 519 votes of the 536 voting. On 14 February, the Assembly voted to pass the powers of the Government of National Defense to the new Assembly. On 17 February, on a proposition by Grévy, Thiers was elected the Chef du pouvoir executif, or Chief Executive of the government. He asked the Assembly that the words "Of the French Republic" be added to his title. He told the Assembly: "I have great admiration for cooks. They call them Chefs. You have named me the Chef of the Executive Power. Do you take me for a cook? Do you take France for a kitchen?" The deputies laughed and agreed to the addition. The new government was promptly recognized by Britain, Italy, Austria, and Russia. For the first time since 1852, France was once again officially a republic.[39]

Chief Executive and end of the fighting

On 19 February, Thiers announced the formation of a new government with nine ministers, a majority of republicans, including Jules Favre and Jules Simon. The first task assigned by the Assembly was to negotiate an end to the War. Thiers traveled with a delegation of five members of the Assembly to Versailles, where Bismarck was waiting. When he arrived at the hotel, he met the Prussian Field Marshal Moltke, who told him, "You are lucky to be negotiating with Bismarck. If it were me, I would occupy your country for thirty years and in that time there would be no more France." At the first meeting, Bismarck demanded the province of Alsace and eight billion francs. Thiers insisted that France could pay no more than five billion francs, and Bismarck reduced the payment, but insisted that Germany must have part of Lorraine and Metz as well. The talks were long and stressful; at one point Thiers, exhausted, broke down and wept. Bismarck helped him to a sofa, covered him with his overcoat, and told him, "Ah, my poor Monsieur Thiers, there is no one but you and I who really love France." The negotiations resumed, and Thiers conceded Alsace and part of Lorraine, in exchange for a reduction in the payment. He told the other French delegates, "If we lose one or two provinces it is not of great importance. There will be another war when France will be victorious, and we will get them back. But the billions we give to Germany now we will never recover." Thiers insisted, however, that France keep the fortress town of Belfort. Bismarck conceded the town, on the condition that, when the armistice was signed, the Prussian army could hold a brief victory parade on the Champs-Élysées, and could remain until the treaty was ratified. Thiers felt he had little choice but to accept.[40]

Thiers and his delegation returned to Bordeaux, and on 28 February, Thiers, sometimes breaking down in tears, read the terms to the Assembly. In the debate that followed, fifty members spoke for and against the peace. The members from Alsace and Lorraine strongly objected, and member Victor Hugo demanded, in the interest of history and posterity, to continue the war. The Deputy Louis Blanc declared that ten million Frenchmen wanted to keep fighting. "But where are they?" Thiers asked. "In this Assembly, elected by universal suffrage, three-quarters of the members want peace." As Thiers predicted, the Assembly voted on 1 March by 546 votes to 107 to accept Bismarck's terms. On 2 March the Germans held their parade on the Champs-Élysées. All the shops were closed and there were no Parisians on the street.[41]

Paris Commune

Once the armistice was finished, the National Assembly held its first session in Versailles, and Thiers traveled to Paris on 15 March with the intention of reopening the government ministries there. He found the city in a state of revolutionary fever. At the time of the armistice, the National Guard in Paris had grown to 380,000. Predominantly working class, most members depended on the 1.5 francs a day they were paid. The Guard had become deeply radicalized by several revolutionary and socialist movements. With the war over, the National Assembly proposed ending their salary. The Guard had also been outraged by the Prussian victory march on the Champs Élysées; they demanded that the war continue. One attempt to overthrow the city government had already taken place, and had been put down with great difficulty. There were just thirty thousand regular army soldiers in the Paris garrison; a large part of the French regular army was still held in German prison camps.[42]

Army depots in the city held 450,000 rifles and two thousand cannons. On 18 March, Thiers sent army units to move the cannons out of Paris. Many cannons were removed without difficulty, but on Montmartre, where the largest park of cannons was located, the army encountered crowds of armed and hostile guardsmen. Fighting broke out, and two army generals were seized and killed by the Guardsman. A general uprising began, and the revolutionaries seized the major government buildings. The guardsmen did not know that Thiers was still in Paris, at the new foreign ministry on the Quai d'Orsay; if they had known he certainly would have been captured and probably killed. Instead, he escaped the city via the Bois de Boulogne and made his way to Versailles. Thiers then followed the same plan that he had proposed to Louis-Philippe during the 1848 Revolution, but which the King had rejected; instead of fighting the insurrection immediately in Paris with the troops he had, he ordered regular army to withdraw to Versailles, to gather its forces, and then, when it was ready, to recapture the city.

While Thiers assembled his forces, including French soldiers just released from the German prison camps, Parisians elected a radical republican and socialist city government on 26 March: the Paris Commune. 224,000 Parisians voted, while 257,000 abstained. The more moderate members elected, including Georges Clemenceau, departed, leaving the Commune under the control of the most militant revolutionary movements. Similar Communes were quickly declared in Lyon, Marseille, and other cities, but were rapidly suppressed by the army. The Central Committee of the Commune declared that, if the French government no longer recognized Paris as the capital of France, Paris and the surrounding Department of the Seine would become an independent republic. Thiers summoned the Assembly in Versailles on 27 March and declared, "There are some enemies of order who claim that we are trying to overthrow the Republic. I give them a formal denial; they are lying to France ... We have accepted this mission, to defend order and to re-organize the country. When order has been re-established, the country will have the liberty to choose as it wishes whatever will be its future destiny." Thiers declared that the country needed to unite behind the Republic; he stated his famous formula, "The Republic is the form of government that divides us the least."[43]

Thiers named Marshal Patrice MacMahon, who had led the French Army during the victorious war to liberate parts of Italy from the Austrians, to command the new Army of Versailles. In early April, the first skirmishes between the army and Commune soldiers took place in the vicinity of Paris. Within Paris, the Commune began to take hostages, including Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris, the curate of the Madeleine and about two hundred priests. They proposed to exchange them for Louis Blanqui, the revolutionary leader imprisoned at Mont-Saint-Michel. Thiers, with the support of the National Assembly, refused, saying he "would not negotiate with murderers", and he feared that the exchange would simply lead to more hostage taking. In response, a mob attacked Thiers' empty house, taking all his personal belongings and later setting fire to the house.

On 21 May, the French army, with 120,000 soldiers, entered the city through an undefended gate. By the end of the 22nd the Army had captured the west of the city and Montmartre, and on the 23rd, they captured most of the center. The Commune soldiers were outnumbered four or five to one, had no single military leader, no plan of defense, and no possibility of aid from the outside. As they retreated, they set fire to the government buildings, including the Tuileries Palace, the State Council at the Palais Royal, the Ministry of Finance, the Prefecture of Police, the Palace of Justice, and the Hôtel de Ville, destroying the city archives. On 24 May the Archbishop of Paris and many of the hostage priests were taken out and shot. The Commune soldiers set up a new defensive line on 25 May and the fighting intensified. Thiers and MacMahon set up their headquarters at the Quai d'Orsay. Despite orders from Thiers and MacMahon, many army units systematically shot the Communard prisoners they had captured. On 26 May, the fighting was centered in Belleville and around the Place du Trône (now Place de la Nation). That day the Commune ordered the execution of thirty-six policemen and ten priests on Rue Haxo. The fighting continued through 28 May, until the capture of Père Lachaise cemetery and the city hall of the 11th arrondissement. On the 29th, the last bastion of the Commune, the fort of Vincennes, surrendered.[44]

The army casualties numbered 873 dead and 6,424 wounded. 6,562 Commune fighters were buried in common graves, and later transferred to city cemeteries. 43,522 alleged Communards and Commune supporters, including 819 women, were captured and taken to Versailles for trial by military courts. Most were released immediately, but after trials by military tribunals, ninety-three were sentenced to death (of whom 23 were executed; the others were sent outside of France), and about ten thousand more sentenced to deportation or prison. Thousands more Commune participants, including a majority of the members of the Commune council, escaped to exile. All were given amnesty in 1879 and 1880, and allowed to return home. Some, including the famous anarchist Louise Michel, quickly returned to political agitation.[45]

Making peace

During the dramatic events of the Commune, France was still officially at war with Prussia and then with the new German Empire. The fighting had stopped, but German soldiers occupied about half the territory of France. Bismarck and the German government were concerned by the Paris uprising, and feared that France would resume fighting the war. Bismarck declared that Germany would not remove its soldiers from France until the French government was solidly established, and twice offered Thiers German soldiers to help suppress it, but Thiers refused.[46]

Once the Commune had fallen to the French Army, Thiers turned his attention to liberating French soil from German occupation. He had lost Alsace and part of Lorraine, with a total population of 1.6 million of the 36.1 million inhabitants of France; the government had a deficit of nearly three billion francs, France owed Germany five billion francs under the terms of peace, which had to be paid largely in gold; and the destruction during the Paris Commune required 232 million francs to repair. Thiers used his considerable financial skills to find the money. He borrowed money from the Bank of France and the Morgan bank in London, and in June 1871 he issued bonds, which brought in over 4 billion francs. In July 1871, Thiers was able to pay the first five hundred million francs of the payment to Germany. In exchange, as they had promised, the Germans withdrew their troops from three departments; the Eure, the Somme, and the lower Seine.[47]

President of the Republic (1871–1873)

Despite his success with the national finances, Thiers was in a precarious political position. France was predominantly rural, religious and conservative, and the National Assembly reflected this. A majority of the Assembly members supported some form of constitutional monarchy, though they were about equally divided between those who wanted a king from the former Bourbon monarchy, and the Orleanists, who wanted a descendant of Louis-Philippe. There were even a few deputies who wanted a descendant of Napoleon III on the throne.

In June 1871, against the wishes of Thiers, the Assembly voted by 472 to 97 to allow exiled members of the Bourbons and Orleans families to return to France. They were led by Henri, Count of Chambord, the heir to the Bourbon throne, who declared his willingness to rule France as Henry V. He received considerable support in the beginning, but lost much of it when he declared that he would replace the French tricolor with the white flag of the Bourbons. Thiers protested that it was not possible to have constitutional monarchy with three different royal dynasties, the Bourbons, the Orleans, and the Bonapartes, all claiming the throne. The republicans in the Assembly, including Léon Gambetta, rallied around Thiers as a defender of the republic.

The appearance of the Count of Chambord provoked a political crisis, which worked to the advantage of Thiers. He persuaded the republicans that he was the least monarchist of the monarchists, and persuaded the monarchists that he was the least republican of the republicans. On 30 August 1871, the Assembly voted 494 to 94 to change the title of Thiers from Chief of the Executive Power to President of the Republic, under the authority of the National Assembly. It was a remarkable political achievement; the Third Republic had been created with the votes of the anti-republican monarchists. In private, he was not very kind to the assembly; he told a friend that "I have an Assembly of 150 insurgents [the republicans] and four hundred poltrons (chicken-hearts). One could say that the real founder of the Republic is the Count of Chambord."[48]

Thiers moved quickly to set up a strong and conservative republic. The Assembly and government remained in Versailles, until the government buildings in Paris could be repaired. Thiers lived in the Prefecture building of Versailles. He considered moving into the official presidential residence in Paris, the Élysée Palace, but his wife rejected the idea, declaring that "we would be in Paris fifteen days before Monsieur Thiers would be assassinated." He did hold receptions and events in the Élysee, travelling back and forth to Paris with a large escort of police. The Assembly voted funds to rebuild his house on Place Saint-Georges in Paris, which had been burned by the Communards, and gave him money to replace his belongings, art collection, and library, which had been looted.

His first priority was to rid the country entirely of the German occupation of the east and north of France. By the end of September 1871, after the payment of 1.5 billion francs, six more departments were liberated, but twelve were still occupied, until the debt could entirely be paid off. The sum amounted to one sixth of the entire budget of the Republic. Within the Assembly, the republicans were gaining at the expense of the constitutional monarchists, but they were also divided into several factions, with Thiers usually among the moderate republicans while Léon Gambetta led the far left. The right was also divided into factions, some wishing a constitutional monarchy under the Orleanist Count of Paris, others under the Bourbon Count of Chambord. It was a very unstable mixture. Early in his presidency, Thiers declared, "In general, the country is wise, but the political parties are not. It is these, and only these, that we have to fear. It is only these which we have to guard against." Thiers wrote late in his memoirs that he would have preferred a constitutional monarchy, but he knew it was impossible at that moment, given the strong majority of republicans, and supporting a monarchy would have been "a violation of my duties toward France; I had as my mission to pacify and to prevent the conflicts of parties." [49]

In January 1872, in partial elections for the National Assembly, Victor Hugo ran for a seat in the National Assembly for Paris as a radical republican against a moderate republican backed by Thiers. Hugo was defeated by 121,000 to 93,000 votes. Of sixteen seats up for election, republicans won eleven and only four were won by monarchists. Thiers wrote, "The great majority of the middle class, businessmen, and country people, without saying expressly that they were for the republic, said "we are for the government of Thiers". Thiers further won the support of the middle class and businessmen by opposing a proposed income tax, which he declared was entirely arbitrary, "inspired by political hatreds and passions." The tax was rejected.[50]

He was a convinced protectionist, wishing to shelter French industry against free trade and foreign competition. On this issue he was in a minority; the Assembly voted 367 to 297 to reduce tariffs on imported goods. Thiers offered his resignation, which was rejected by the Assembly; with only eight dissenting voices, they insisted that he remain as president. Thiers was an advocate of obligatory long military service; he pushed through a law requiring obligatory service of five years for French men. To the monarchists, he seemed more and more like a republican. He told them, "I found the Republic already made. A monarchy is impossible because there are three dynasties for a single throne." In 1873, the monarchists of the Assembly, led by the Duke de Broglie, began looking for a way to bring about his downfall.

The primary goal of Thiers in 1873 was to pay off the debt to Germany, to liberate the last French territory occupied by the Germans. France still owed three billion francs, more than the national budget, with final payment due in August 1875. He made agreements with the major fifty-five banks of Europe, and issued bonds which, based on the good credit of France, brought in more than the amount required. Thiers signed a new convention with Germany on 15 March 1873, calling for the Germans to leave the last four French departments they held, Ardennes, Vosges, Meurthe-et-Moselle and Meuse by July 1873, two years ahead of schedule. Germany retained only the fortress of Verdun, and the territory of a radius of three kilometers around it. The National Assembly voted a special resolution to thank Thiers for liberating French territory ahead of schedule. The right wing deputies abstained, but it passed with the full support of the republicans. After the resolution passed, Thiers was congratulated by his longtime friend and ally, Jules Simon: "Now you just have to name a successor." Thiers responded, "but there's no one!" Simon replied, "They have Marshal MacMahon." "Oh, about that," Thiers responded, "Don't worry, he would never accept."[51]

Downfall (1873)