An assessment of heavy metal contaminants related to cannabis-based products in the South African market

Contents

| tibiae | |

|---|---|

Position of tibia (shown in red) | |

Cross section of the leg showing the different compartments (latin terminology) | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | Knee, ankle, superior and inferior tibiofibular joint |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | (os) tibia |

| MeSH | D013977 |

| TA98 | A02.5.06.001 |

| TA2 | 1397 |

| FMA | 24476 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The tibia (/ˈtɪbiə/; pl.: tibiae /ˈtɪbii/ or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects the knee with the ankle. The tibia is found on the medial side of the leg next to the fibula and closer to the median plane. The tibia is connected to the fibula by the interosseous membrane of leg, forming a type of fibrous joint called a syndesmosis with very little movement. The tibia is named for the flute tibia. It is the second largest bone in the human body, after the femur. The leg bones are the strongest long bones as they support the rest of the body.

Structure

In human anatomy, the tibia is the second largest bone next to the femur. As in other vertebrates the tibia is one of two bones in the lower leg, the other being the fibula, and is a component of the knee and ankle joints.

The ossification or formation of the bone starts from three centers, one in the shaft and one in each extremity.

The tibia is categorized as a long bone and is as such composed of a diaphysis and two epiphyses. The diaphysis is the midsection of the tibia, also known as the shaft or body. While the epiphyses are the two rounded extremities of the bone; an upper (also known as superior or proximal) closest to the thigh and a lower (also known as inferior or distal) closest to the foot. The tibia is most contracted in the lower third and the distal extremity is smaller than the proximal.

Upper extremity

Condyles of tibia

The proximal or upper extremity of the tibia is expanded in the transverse plane with a medial and lateral condyle, which are both flattened in the horizontal plane. The medial condyle is the larger of the two and is better supported over the shaft. The upper surfaces of the condyles articulate with the femur to form the tibiofemoral joint, the weightbearing part of the kneejoint.[1]

The medial and lateral condyle are separated by the intercondylar area, where the cruciate ligaments and the menisci attach. Here the medial and lateral intercondylar tubercle forms the intercondylar eminence. Together with the medial and lateral condyle the intercondylar region forms the tibial plateau, which both articulates with and is anchored to the lower extremity of the femur. The intercondylar eminence divides the intercondylar area into an anterior and posterior part. The anterolateral region of the anterior intercondylar area are perforated by numerous small openings for nutrient arteries.[1] The articular surfaces of both condyles are concave, particularly centrally. The flatter outer margins are in contact with the menisci. The medial condyles superior surface is oval in form and extends laterally onto the side of medial intercondylar tubercle. The lateral condyles superior surface is more circular in form and its medial edge extends onto the side of the lateral intercondylar tubercle. The posterior surface of the medial condyle bears a horizontal groove for part of the attachment of the semimembranosus muscle, whereas the lateral condyle has a circular facet for articulation with the head of the fibula.[1] Beneath the condyles is the tibial tuberosity which serves for attachment of the patellar ligament, a continuation of the quadriceps femoris muscle.[1]

Facets

The superior articular surface presents two smooth articular facets.

- The medial facet, oval in shape, is slightly concave from side to side, and from before backward.

- The lateral, nearly circular, is concave from side to side, but slightly convex from before backward, especially at its posterior part, where it is prolonged on to the posterior surface for a short distance.

The central portions of these facets articulate with the condyles of the femur, while their peripheral portions support the menisci of the knee joint, which here intervene between the two bones.

Intercondyloid eminence

Between the articular facets in the intercondylar area, but nearer the posterior than the anterior aspect of the bone, is the intercondyloid eminence (spine of tibia), surmounted on either side by a prominent tubercle, on to the sides of which the articular facets are prolonged; in front of and behind the intercondyloid eminence are rough depressions for the attachment of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments and the menisci.

Surfaces

The anterior surfaces of the condyles are continuous with one another, forming a large somewhat flattened area; this area is triangular, broad above, and perforated by large vascular foramina; narrow below where it ends in a large oblong elevation, the tuberosity of the tibia, which gives attachment to the patellar ligament; a bursa intervenes between the deep surface of the ligament and the part of the bone immediately above the tuberosity.

Posteriorly, the condyles are separated from each other by a shallow depression, the posterior intercondyloid fossa, which gives attachment to part of the posterior cruciate ligament of the knee-joint. The medial condyle presents posteriorly a deep transverse groove, for the insertion of the tendon of the semimembranosus.

Its medial surface is convex, rough, and prominent; it gives attachment to the medial collateral ligament.

The lateral condyle presents posteriorly a flat articular facet, nearly circular in form, directed downward, backward, and lateralward, for articulation with the head of the fibula. Its lateral surface is convex, rough, and prominent in front: on it is an eminence, situated on a level with the upper border of the tuberosity and at the junction of its anterior and lateral surfaces, for the attachment of the iliotibial band. Just below this a part of the extensor digitorum longus takes origin and a slip from the tendon of the biceps femoris is inserted.

Shaft

The shaft or body of the tibia is triangular in cross-section and forms three borders: an anterior, medial, and lateral or interosseous border. These three borders form three surfaces: the medial, lateral, and posterior.[2]

Borders

The anterior crest or border, the most prominent of the three, commences above at the tuberosity, and ends below at the anterior margin of the medial malleolus. It is sinuous and prominent in the upper two-thirds of its extent, but smooth and rounded below; it gives attachment to the deep fascia of the leg.

The medial border is smooth and rounded above and below, but more prominent in the center. It begins at the back part of the medial condyle, and ends at the posterior border of the medial malleolus; its upper part gives attachment to the tibial collateral ligament of the knee-joint to the extent of about 5 cm., and insertion to some fibers of the popliteus muscle. From its middle third some fibers of the soleus and flexor digitorum longus muscles take origin.

The interosseous crest or lateral border is thin and prominent, especially its central part, and gives attachment to the interosseous membrane; it commences above in front of the fibular articular facet, and bifurcates below, to form the boundaries of a triangular rough surface, for the attachment of the interosseous ligament connecting the tibia and fibula.

Surfaces

The medial surface is smooth, convex, and broader above than below; its upper third, directed forward and medialward, is covered by the aponeurosis derived from the tendon of the sartorius, and by the tendons of the Gracilis and Semitendinosus, all of which are inserted nearly as far forward as the anterior crest; in the rest of its extent it is subcutaneous.

The lateral surface is narrower than the medial; its upper two-thirds present a shallow groove for the origin of the Tibialis anterior; its lower third is smooth, convex, curves gradually forward to the anterior aspect of the bone, and is covered by the tendons of the Tibialis anterior, Extensor hallucis longus, and Extensor digitorum longus, arranged in this order from the medial side.

The posterior surface presents, at its upper part, a prominent ridge, the popliteal line, which extends obliquely downward from the back part of the articular facet for the fibula to the medial border, at the junction of its upper and middle thirds; it marks the lower limit of the insertion of the Popliteus, serves for the attachment of the fascia covering this muscle, and gives origin to part of the Soleus, Flexor digitorum longus, and Tibialis posterior. The triangular area, above this line, gives insertion to the Popliteus. The middle third of the posterior surface is divided by a vertical ridge into two parts; the ridge begins at the popliteal line and is well-marked above, but indistinct below; the medial and broader portion gives origin to the Flexor digitorum longus, the lateral and narrower to part of the Tibialis posterior. The remaining part of the posterior surface is smooth and covered by the Tibialis posterior, Flexor digitorum longus, and Flexor hallucis longus. Immediately below the popliteal line is the nutrient foramen, which is large and directed obliquely downward.

Lower extremity

The distal end of the tibia is much smaller than the proximal end and presents five surfaces; it is prolonged downward on its medial side as a strong pyramidal process, the medial malleolus. The lower extremity of the tibia together with the fibula and talus forms the ankle joint.

Surfaces

The inferior articular surface is quadrilateral, and smooth for articulation with the talus. It is concave from before backward, broader in front than behind, and traversed from before backward by a slight elevation, separating two depressions. It is continuous with that on the medial malleolus.

The anterior surface of the lower extremity is smooth and rounded above, and covered by the tendons of the Extensor muscles; its lower margin presents a rough transverse depression for the attachment of the articular capsule of the ankle-joint.

The posterior surface is traversed by a shallow groove directed obliquely downward and medialward, continuous with a similar groove on the posterior surface of the talus and serving for the passage of the tendon of the Flexor hallucis longus.

The lateral surface presents a triangular rough depression for the attachment of the inferior interosseous ligament connecting it with the fibula; the lower part of this depression is smooth, covered with cartilage in the fresh state, and articulates with the fibula. The surface is bounded by two prominent borders (the anterior and posterior colliculi), continuous above with the interosseous crest; they afford attachment to the anterior and posterior ligaments of the lateral malleolus.

The medial surface – see medial malleolus for details.

Fractures

Ankle fractures of the tibia have several classification systems based on location or mechanism:

- Medial malleolus – Herscovici classification

- Posterior malleolus – Haruguchi classification

- Mechanism – Lauge-Hansen classification

Blood supply

The tibia is supplied with blood from two sources: A nutrient artery, as the main source, and periosteal vessels derived from the anterior tibial artery.[3]

Joints

The tibia is a part of four joints; the knee, ankle, superior and inferior tibiofibular joint.

In the knee the tibia forms one of the two articulations with the femur, often referred to as the tibiofemoral components of the knee joint.;[4][5] it is the weightbearing part of the knee joint.[2] The tibiofibular joints are the articulations between the tibia and fibula which allows very little movement.[citation needed] The proximal tibiofibular joint is a small plane joint. The joint is formed between the undersurface of the lateral tibial condyle and the head of fibula. The joint capsule is reinforced by anterior and posterior ligament of the head of the fibula.[2] The distal tibiofibular joint (tibiofibular syndesmosis) is formed by the rough, convex surface of the medial side of the distal end of the fibula, and a rough concave surface on the lateral side of the tibia.[2]

The part of the ankle joint known as the talocrural joint, is a synovial hinge joint that connects the distal ends of the tibia and fibula in the lower limb with the proximal end of the talus. The articulation between the tibia and the talus bears more weight than between the smaller fibula and the talus.[citation needed]

Development

The tibia is ossified from three centers: a primary center for the diaphysis (shaft) and a secondary center for each epiphysis (extremity). Ossification begins in the center of the body, about the seventh week of fetal life, and gradually extends toward the extremities.

The center for the upper epiphysis appears before or shortly after birth at close to 34 weeks gestation; it is flattened in form, and has a thin tongue-shaped process in front, which forms the tuberosity; that for the lower epiphysis appears in the second year.

The lower epiphysis fuses with the tibial shaft at about the eighteenth, and the upper one fuses about the twentieth year.

Two additional centers occasionally exist, one for the tongue-shaped process of the upper epiphysis, which forms the tuberosity, and one for the medial malleolus.

Function

Muscle attachments

| Muscle | Direction | Attachment[6] |

| Tensor fasciae latae muscle | Insertion | Gerdy's tubercle |

| Quadriceps femoris muscle | Insertion | Tuberosity of the tibia |

| Sartorius muscle | Insertion | Pes anserinus |

| Gracilis muscle | Insertion | Pes anserinus |

| Semitendinosus muscle | Insertion | Pes anserinus |

| Horizontal head of the semimembranosus muscle | Insertion | Medial condyle |

| Popliteus muscle | Insertion | Posterior side of the tibia over the soleal line |

| Tibialis anterior muscle | Origin | Lateral side of the tibia |

| Extensor digitorum longus muscle | Origin | Lateral condyle |

| Soleus muscle | Origin | Posterior side of the tibia under the soleal line |

| Flexor digitorum longus muscle | Origin | Posterior side of the tibia under the soleal line |

Strength

The tibia has been modeled as taking an axial force during walking that is up to 4.7 bodyweight. Its bending moment in the sagittal plane in the late stance phase is up to 71.6 bodyweight times millimetre.[7]

Clinical significance

Fracture

Fractures of the tibia can be divided into those that only involve the tibia; bumper fracture, Segond fracture, Gosselin fracture, toddler's fracture, and those including both the tibia and fibula; trimalleolar fracture, bimalleolar fracture, Pott's fracture.

Society and culture

In Judaism, the tibia, or shankbone, of a goat or sheep is used in the Passover Seder plate.

Other animals

The structure of the tibia in most other tetrapods is essentially similar to that in humans. The tuberosity of the tibia, a crest to which the patellar ligament attaches in mammals, is instead the point for the tendon of the quadriceps muscle in reptiles, birds, and amphibians, which have no patella.[8]

Additional images

-

Shape of right tibia

-

3D image

-

Longitudinal section of tibia showing interior

-

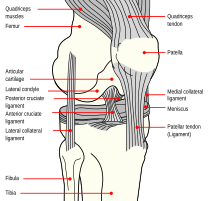

Right knee-joint. Anterior view.

-

Right knee joint from the front, showing interior ligaments

-

Left knee joint from behind, showing interior ligaments

-

Left talocrural joint

-

Coronal section through right talocrural and talocalcaneal joints

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view

-

Bones of the right leg. Anterior surface

-

Bones of the right leg. Posterior surface

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Tibia Anatomy

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 256 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 256 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c d Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, A. Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2010). Gray´s Anatomy for Students (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 558–560. ISBN 978-0-443-06952-9.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, A. Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2010). Gray´s Anatomy for Students (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 584–588. ISBN 978-0-443-06952-9.

- ^ Nelson G, Kelly P, Peterson L, Janes J (1960). "Blood supply of the human tibia". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 42-A (4): 625–36. doi:10.2106/00004623-196042040-00007. PMID 13854090.

- ^ Rytter S, Egund N, Jensen LK, Bonde JP (2009). "Occupational kneeling and radiographic tibiofemoral and patellofemoral osteoarthritis". J Occup Med Toxicol. 4 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/1745-6673-4-19. PMC 2726153. PMID 19594940.

- ^ Gill TJ, Van de Velde SK, Wing DW, Oh LS, Hosseini A, Li G (December 2009). "Tibiofemoral and patellofemoral kinematics after reconstruction of an isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury: in vivo analysis during lunge". Am J Sports Med. 37 (12): 2377–85. doi:10.1177/0363546509341829. PMC 3832057. PMID 19726621.

- ^ Bojsen-Møller, Finn; Simonsen, Erik B.; Tranum-Jensen, Jørgen (2001). Bevægeapparatets anatomi [Anatomy of the Locomotive Apparatus] (in Danish) (12th ed.). Munksgaard Danmark. pp. 364–367. ISBN 978-87-628-0307-7.

- ^ Wehner, T; Claes, L; Simon, U (2009). "Internal loads in the human tibia during gait". Clin Biomech. 24 (3): 299–302. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.12.007. PMID 19185959.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 205. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.