A sustainable approach for the reliable and simultaneous determination of terpenoids and cannabinoids in hemp inflorescences by vacuum-assisted headspace solid-phase microextraction

Contents

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sodium chlorite

| |||

| Other names

Chlorous acid, sodium salt

Textone | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.942 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII |

| ||

| UN number | 1496 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

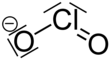

| NaClO2 | |||

| Molar mass | 90.442 g/mol (anhydrous) 144.487 g/mol (trihydrate) | ||

| Appearance | white solid | ||

| Odor | odorless | ||

| Density | 2.468 g/cm3, solid | ||

| Melting point | anhydrous decomposes at 180–200 °C trihydrate decomposes at 38 °C | ||

| 75.8 g/100 mL (25 °C) 122 g/100 mL (60 °C) | |||

| Solubility | slightly soluble in methanol, ethanol | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 10-11 | ||

| Structure | |||

| monoclinic | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

-307.0 kJ/mol | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| D03AX11 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Ingestion hazards

|

Category 3 | ||

Inhalation hazards

|

Category 2 | ||

Eye hazards

|

Category 1 | ||

Skin hazards

|

Category 1B | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H272, H301, H310, H314, H330, H400 | |||

| P210, P220, P221, P260, P262, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P284, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P305+P351+P338, P310, P361, P363, P370+P378, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

350 mg/kg (rat, oral) | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | SDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other anions

|

Sodium chloride Sodium hypochlorite Sodium chlorate Sodium perchlorate | ||

Other cations

|

Potassium chlorite Barium chlorite | ||

Related compounds

|

Chlorine dioxide Chlorous acid | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Sodium chlorite (NaClO2) is a chemical compound used in the manufacturing of paper and as a disinfectant.

Use

The main application of sodium chlorite is the generation of chlorine dioxide for bleaching and stripping of textiles, pulp, and paper. It is also used for disinfection of municipal water treatment plants after conversion to chlorine dioxide.[1]: 2 An advantage in this application, as compared to the more commonly used chlorine, is that trihalomethanes (such as chloroform) are not produced from organic contaminants.[1]: 25, 33 Chlorine dioxide generated from sodium chlorite is approved by FDA under some conditions for disinfecting water used to wash fruits, vegetables, and poultry.[2][full citation needed][3]

Sodium chlorite, NaClO2, sometimes in combination with zinc chloride, also finds application as a component in therapeutic rinses, mouthwashes,[4][5] toothpastes and gels, mouth sprays, as preservative in eye drops,[6] and in contact lens cleaning solution under the trade name Purite.

It is also used for sanitizing air ducts and HVAC/R systems and animal containment areas (walls, floors, and other surfaces).

Chemical reagent

In organic synthesis, sodium chlorite is frequently used as a reagent in the Pinnick oxidation for the oxidation of aldehydes to carboxylic acids. The reaction is usually performed in monosodium phosphate buffered solution in the presence of a chlorine scavenger (usually 2-methyl-2-butene).[7]

In 2005, sodium chlorite was used as an oxidizing agent to convert alkyl furans to the corresponding 4-oxo-2-alkenoic acids in a simple one pot synthesis.[8]

Acidified sodium chlorite

Mixing sodium chlorite solution with a weak food-grade acid solution (commonly citric acid), both stable, produces short-lived acidified sodium chlorite (ASC) which has potent decontaminating properties. Upon mixing the main active ingredient, chlorous acid is produced in equilibrium with chlorite anion. The proportion varies with pH, temperature, and other factors, ranging from approximately 5–35% chlorous acid with 65–95% chlorite; more acidic solutions result in a higher proportion of chlorous acid. Chlorous acid breaks down to chlorine dioxide which in turn breaks down to chlorite anion and ultimately chloride anion. ASC is used for sanitation of the hard surfaces which come in contact with food and as a wash or rinse for a variety of foods including red meat, poultry, seafood, fruits and vegetables. Because the oxo-chlorine compounds are unstable when properly prepared, there should be no measurable residue on food if treated appropriately.[9][10] ASC also is used as a teat dip for control of mastitis in dairy cattle.[11]

Use in public crises

The U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development, and Engineering Center produced a portable "no power required" method of generating chlorine dioxide, known as ClO2, gas, described as one of the best biocides available for combating contaminants, which range from benign microbes and food pathogens to Category A Bioterror agents. In the weeks after the 9/11 attacks when anthrax was sent in letters to public officials, hazardous materials teams used ClO2 to decontaminate the Hart Senate Office Building, and the Brentwood Postal Facility.[12]

In addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has posted a list of many disinfectants that meet its criteria for use in environmental measures against the causative coronavirus.[13][14] Some are based on sodium chlorite that is activated into chlorine dioxide, though differing formulations are used in each product. Many other products on the EPA list contain sodium hypochlorite, which is similar in name but should not be confused with sodium chlorite because they have very different modes of chemical action.

Safety

Sodium chlorite, like many oxidizing agents, should be protected from inadvertent contamination by organic materials to avoid the formation of an explosive mixture. The chemical is stable in pure form and does not explode on percussive impact, unless organic contaminants are present, such as on a greasy hammer striking the chemical on an anvil.[15] It also easily ignites by friction if combined with a reducing agent like powdered sugar, sulfur or red phosphorus.

Toxicity

Sodium chlorite is a strong oxidant and can therefore be expected to cause clinical symptoms similar to the well known sodium chlorate: methemoglobinemia, hemolysis, kidney failure.[16] A dose of 10-15 grams of sodium chlorate can be lethal.[17] Methemoglobemia had been demonstrated in rats and cats,[18] and recent studies by the EMEA have confirmed that the clinical symptomatology is very similar to the one caused by sodium chlorate in rats, mice, rabbits, and green monkeys.[19]

There is only one human case in the medical literature of chlorite poisoning.[20] It seems to confirm that the toxicity is equal to sodium chlorate. From the analogy with sodium chlorate, even small amounts of about 1 gram can be expected to cause nausea, vomiting and even life-threatening hemolysis in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficient persons.

The EPA has set a maximum contaminant level of 1 milligram of chlorite per liter (1 mg/L) in drinking water.[21]

Sellers of “Miracle Mineral Solution”, a mixture of sodium chlorite and citric acid also known as "MMS" that is promoted as a cure-all have been convicted, fined, or otherwise disciplined in multiple jurisdictions around the world. MMS products were variously referred to as snake oil and complete quackery. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued multiple warnings against consuming MMS.[22] [23] [24][25] [26][27] [28][29][30]

Manufacture

The free acid, chlorous acid, HClO2, is only stable at low concentrations. Since it cannot be concentrated, it is not a commercial product. However, the corresponding sodium salt, sodium chlorite, NaClO2 is stable and inexpensive enough to be commercially available. The corresponding salts of heavy metals (Ag+, Hg+, Tl+, Pb2+, and also Cu2+ and NH4+) decompose explosively with heat or shock.

Sodium chlorite is derived indirectly from sodium chlorate, NaClO3. First, sodium chlorate is reduced to chlorine dioxide, typically in a strong acid solution using reducing agents such as sodium sulfite, sulfur dioxide, or hydrochloric acid. This intermediate is then absorbed into a solution of aqueous sodium hydroxide where another reducing agent converts it to sodium chlorite. Even hydrogen peroxide can be used as the reducing agent, giving oxygen gas as its byproduct rather than other inorganic salts or materials that could contaminate the desired product.[31]

General references

- "Chemistry of the Elements", N.N. Greenwood and A. Earnshaw, Pergamon Press, 1984.

- "Kirk-Othmer Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry", Martin Grayson, Editor, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1985

References

- ^ a b EPA Guidance Manual, chapter 4: Chlorine dioxide (PDF), US Environmental Protection Agency, archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-11, retrieved 2012-02-27

- ^ "Chlorine dioxide" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- ^ "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ Cohen J (2008-05-13). "New mouthwashes may help take bad breath away". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2012-06-26.

- ^ "SmartMouth 2 Step Mouth Rinse". dentist.net. Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Blink Tears

- ^ Bal BS, Childers WE, Pinnick HW (1981). "Oxidation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes". Tetrahedron (abstract). 37 (11): 2091–2096. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97963-3.

- ^ Annangudi SP, Sun M, Salomon RG (2005). "An efficient synthesis of 4-oxo-2-alkenoic acids from 2-alkyl furans". Synlett (abstract). 9 (9): 1468–1470. doi:10.1055/s-2005-869833.

- ^ Acidified sodium chlorite handling/processing (PDF), Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA), July 21, 2008, archived from the original on April 8, 2013, retrieved December 9, 2012

- ^ Rao MV (2007), Acidified sodium chlorite (ACS), chemical and technical assessment (PDF), Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, archived (PDF) from the original on December 3, 2012, retrieved December 9, 2012

- ^ Hillerton J, Cooper J, Morelli J (2007). "Preventing Bovine Mastitis by a Postmilking Teat Disinfectant Containing Acidified Sodium Chlorite". Journal of Dairy Science. 90 (3): 1201–1208. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(07)71607-7. PMID 17297095.

- ^ Natick plays key role in helping to fight spread of Ebola Archived 2015-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 23/01/2016

- ^ US EPA O (2020-03-13). "List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2". US EPA. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- ^ "How we know disinfectants should kill the COVID-19 coronavirus". Chemical & Engineering News. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ Taylor MC (1940). "Sodium Chlorite Properties and Reactions". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 32 (7): 899–903. doi:10.1021/ie50367a007. S2CID 96222235.

- ^ Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies, McGraw-Hill Professional; 8th edition (March 28, 2006), ISBN 978-0-07-143763-9

- ^ "Chlorates". PoisonCentre.be (in French). Archived from the original on 2012-12-11. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ^ Clinical Toxicology of Commercial Products. Robert E. Gosselin, Roger P. Smith, Harold C. Hodge, Jeannet Braddock. Uitgever: Williams & Wilkins; 5 edition (September 1984) ISBN 978-0-683-03632-9

- ^ "Sodium Chlorite — Summary Report" (PDF). European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products — Veterinary Medicines Evaluation Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Lin JL, Lim PS (1993). "Acute sodium chlorite poisoning associated with renal failure". Ren Fail. 15 (5): 645–8. doi:10.3109/08860229309069417. PMID 8290712.

- ^ "ATSDR: ToxFAQs for Chlorine Dioxide and Chlorite". Archived from the original on 2012-07-02.

- ^ "Seller of "Miracle Mineral Solution" Convicted for Marketing Toxic Chemical as a Miracle Cure". United States Department of Justice. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "Assurance of Voluntary Compliance - Kerri Rivera" (PDF). NBC Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leanne Rita Vassallo and Aaron David Smith (FCA 954 August 20, 2009), Text, archived from the original on November 13, 2014.

- ^ Pulkkinen L (August 3, 2009). "Sexy stories, bogus cures lead to action by state AG". SeattlePI.com. seattlepi.com staff. OCLC 3734418. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Washington Attorney General reels in refunds for consumers hooked by Aussies' quack medicine web sites" (Press release). Washington State Office of the Attorney General. March 8, 2010. Archived from the original on December 7, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Aussie net scammers stung after $1.2m haul". ITnews for Australian Business. Haymarket Media. Aug 26, 2009. Archived from the original on September 20, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Woman told to stop selling cancer 'miracle drug'". ABC News. Australia. April 23, 2009. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Unregistered health provider ordered to stop misleading cancer patients" (Press release). Minister for Tourism and Fair Trading, The Honourable Peter Lawlor. April 23, 2009. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Mole B (2019-08-14). "People are still drinking bleach—and vomiting and pooping their guts out". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- ^ Qian Y, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Zhang L (2007). "A clean production process of sodium chlorite from sodium chlorate". Journal of Cleaner Production. 15 (10): 920–926. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.07.008.