The current state of knowledge on imaging informatics: A survey among Spanish radiologists

| Full article title | The current state of knowledge on imaging informatics: A survey among Spanish radiologists |

|---|---|

| Journal | Insights into Imaging |

| Author(s) | Eiroa, Daniel; Antolín, Andreu; Ascanio, Mónica F.d.C.; Ortiz, Violeta P.; Escobar, Manuel; Roson, Nuria |

| Author affiliation(s) | Hospital Universitario Valle de Hebrón, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria |

| Primary contact | Email: danieldomingo dot eiroa dot idi at gencat dot cat |

| Year published | 2022 |

| Volume and issue | 13 |

| Page(s) | 34 |

| DOI | 10.1186/s13244-022-01164-0 |

| ISSN | 1869-4101 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13244-022-01164-0 |

| Download | https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s13244-022-01164-0.pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Background: There is growing concern about the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on radiology and the future of the profession. The aim of this study is to evaluate general knowledge and concerns about trends on imaging informatics among radiologists working in Spain (residents and attending physicians). For this purpose, an online survey among radiologists working in Spain was conducted with questions related to knowledge about terminology and technologies, need for a regulated academic training on AI, and concerns about the implications of the use of these technologies.

Results: A total of 223 radiologists answered the survey, of whom 23.3% were residents and 76.7% were attending physicians. General terms such as "AI" and "algorithm" had been heard of or read in at least 75.8% and 57.4% of the cases, respectively, while more specific terms were scarcely known. All the respondents considered that they should pursue academic training in medical informatics and new technologies, and 92.9% of them reckoned this preparation should be incorporated in the training program of the specialty. Patient safety was found to be the main concern for 54.2% of the respondents. Job loss was not seen as a peril by 45.7% of the participants.

Conclusions: Although there is a lack of knowledge about AI among Spanish radiologists, there is a will to explore such topics and a general belief that radiologists should be trained in these matters. Based on the results, a consensus is needed to change the current training curriculum to better prepare future radiologists.

Key points: Spanish radiologists desire to delve deeper into imaging informatics. Patient safety and adaptation to new technologies are the main concerns. A change on radiology education is needed to include artificial intelligence.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, medical informatics, medical education, surveys and questionnaires, radiology

Introduction

There is no doubt that the upsurge of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, paired with the high amount of digital data generated in radiology, is changing this medical specialty. ML is already used in different imaging modalities such as CAD (computer-aided design) systems for breast cancer screening on mammography[1] or nodule detection on thoracic CT or radiography.[2] DL algorithms, in particular convolutional networks, are a promising technique for processing medical imaging data not only in tasks like image classification, object detection, segmentation, or registration[3], but also on dose optimization, creation and maintenance of biobanks, and structured reporting among others.[4]

More than 50,000 articles are returned when the search “Radiology” AND “Artificial Intelligence” OR “Deep Learning” OR “Machine Learning” is performed in the PubMed medical research engine, with a “quasi-exponential” slope for the last 10 years. Such is the concern that both the European Society of Radiology (ESR) and the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) have their own specialized internet portals dedicated to artificial intelligence (AI)[5][6], and the latter has even published a peer-reviewed journal fully dedicated to it.[7]

For this reason, there is growing concern among radiologists about the future of the profession. Some believe that radiologists will become obsolete in a few years, and others, such as the aforementioned societies[4][8], have a more conservative stance in which AI will enhance the role of the radiologist and turn the job from volume-based to value-based.[9] Regardless of particular opinions, the irruption of AI in the radiological field, as well as its progressive integration into clinical practice, will bring a radical change in radiology as we currently know it.

The aim of this study is to evaluate general knowledge and concerns about trends on imaging informatics among radiologists currently working in Spain (both residents and attending physicians). All those respondents who had completed residency at the time of the survey are referred to as "attending physicians" throughout the text.

Methods

An online survey using Google Forms was designed by the authors, composed of 20 questions related to the level of knowledge about trending terminology and technologies according to the most recent and relevant literature[4][8][10], the need for a regulated academic training, and concerns about the implications of the widespread use of these technologies in the clinical setting, both ethics- and workforce-related. A summary of the survey is displayed in Table 1.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A link to the survey was distributed among radiologists working in Spain, who were asked to share and publicize it, as widely as possible, among colleagues throughout the country after requesting their permission. It was also shared by some of the regional subsidiaries of the Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (SERAM). It remained open for 62 days, between July 30 and September 30, 2019. Radiologists not working in Spain were excluded.

Responses were stored in a spreadsheet (Google Forms) that was later transformed into a comma-separated value file that was loaded into a Jupyter Notebook using the Python (v 3.4) pandas (v 1.1.4) library for data exploration and statistical analysis. To facilitate analysis and drawing of conclusions, the answers in the Concerns section were grouped into three categories: not concerned (options 1 and 2), indifferent (option 3), and concerned (options 4 and 5). In the instances where group comparison was made between residents and attending physicians, the Chi-square was used (scikit-learn v 0.24.0). Yates’ correction for continuity was applied where necessary. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Confidence intervals are not provided since the survey was purely descriptive. The results are expressed in percentages of the total answers throughout the manuscript.

Results

In the span of two months, a total of 223 radiologists answered the survey, of whom 52 (23.3%) were residents and 171 (76.7%) were attending physicians. When comparing to the current distribution of members in SERAM (836 residents and 5139 nonresidents)[11], we found that we had a greater proportion of residents than expected (p < 0.05).

Regarding attending radiologists, 50.9% worked exclusively in the public setting, while 5.8% worked only in the private sector and 38.6% combines public and private dedication. The same proportion (39.2%) had either fewer than 10 years or more than 20 years of working experience.

As per the residents, 44.2% were in their second year of specialty. Upon finishing, 63.5% desire to work in the public setting, mostly with some private dedication (55.8%). 32.7% had not yet decided on their preferred work setting. A summary of the results is shown in Table 2.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

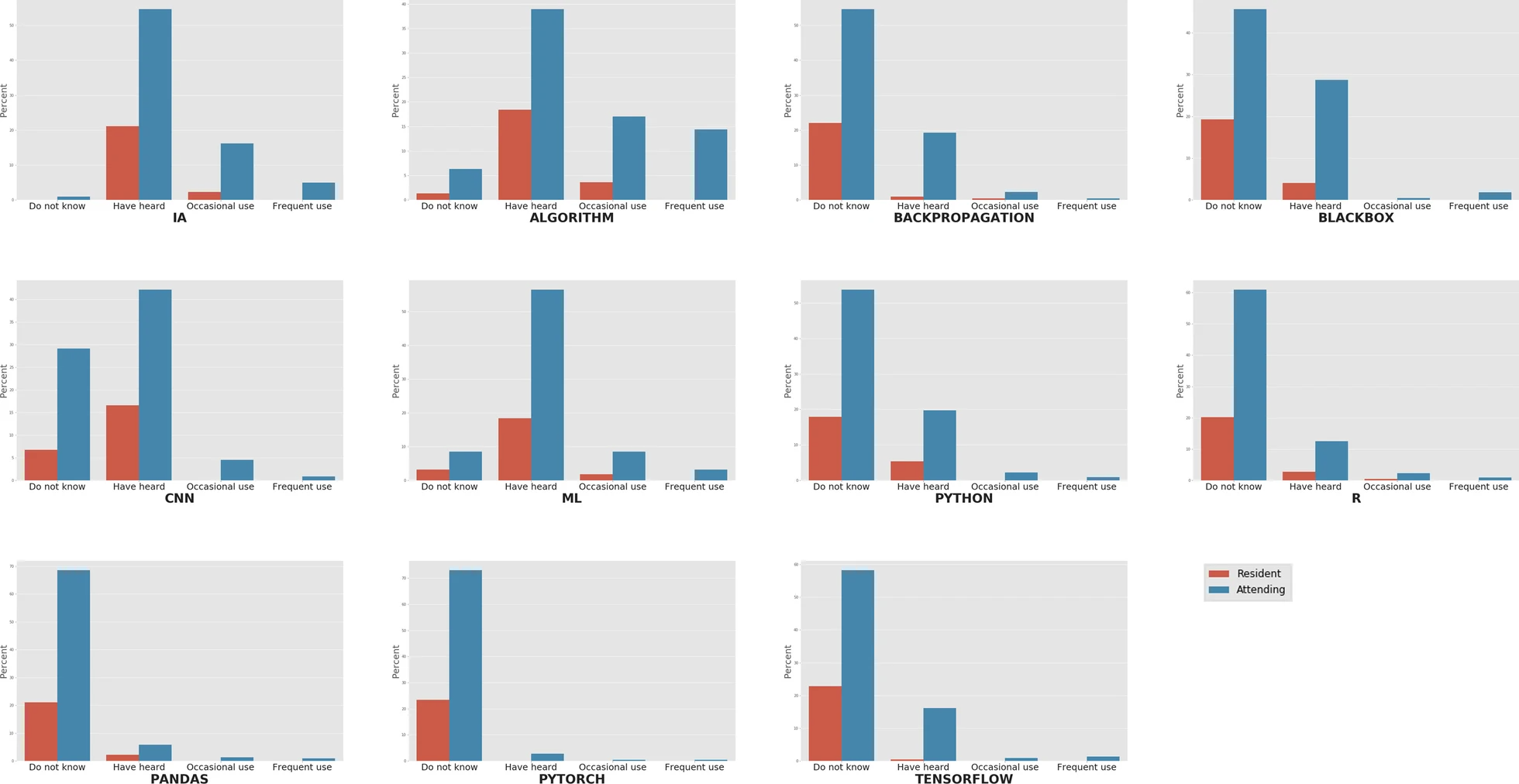

With respect to the terminology and technologies, most of the underlying technologies used in deep learning remained unknown to the survey participants, including Python (71.7%), R (81.2%), PyTorch (96.4%) and TensorFlow (81.2%). Conversely, general terms like "artificial intelligence" and "algorithm" had been heard of or read in at least 75.8% and 57.4% of the cases, respectively (Fig. 1). Statistical significance was found for "artificial intelligence," "algorithm," "backpropagation," "blackbox," and "TensorFlow" (Table 3). According to Pearson's residuals, this significance is mainly due to a higher proportion of residents showing occasional use or knowledge only.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

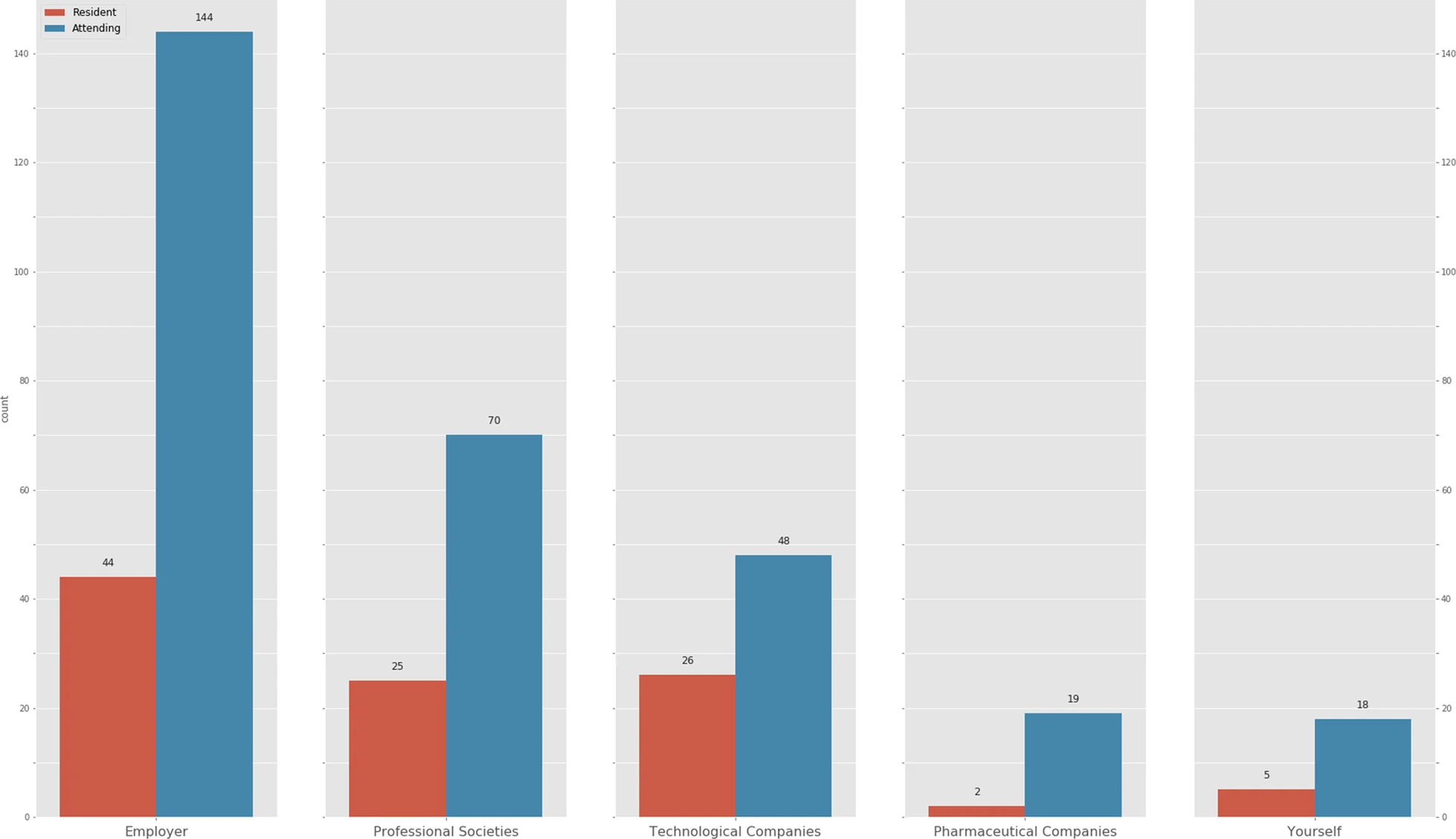

All the respondents (100%) recognize that they should pursue academic training in medical informatics and new technologies. These skills and competencies should be incorporated in the training program of the specialty according to 92.9%, although 76.8% reckon that there is no time during the four-year Spanish residency period to include them. Most of the respondents (84.3%) consider that this training should be financially covered by the employing organization (Fig. 2). No significant differences were observed between groups, except for technological companies, chosen by a bigger proportion of residents (50% vs. 28.1%, p = 0.006) (Table 4).

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

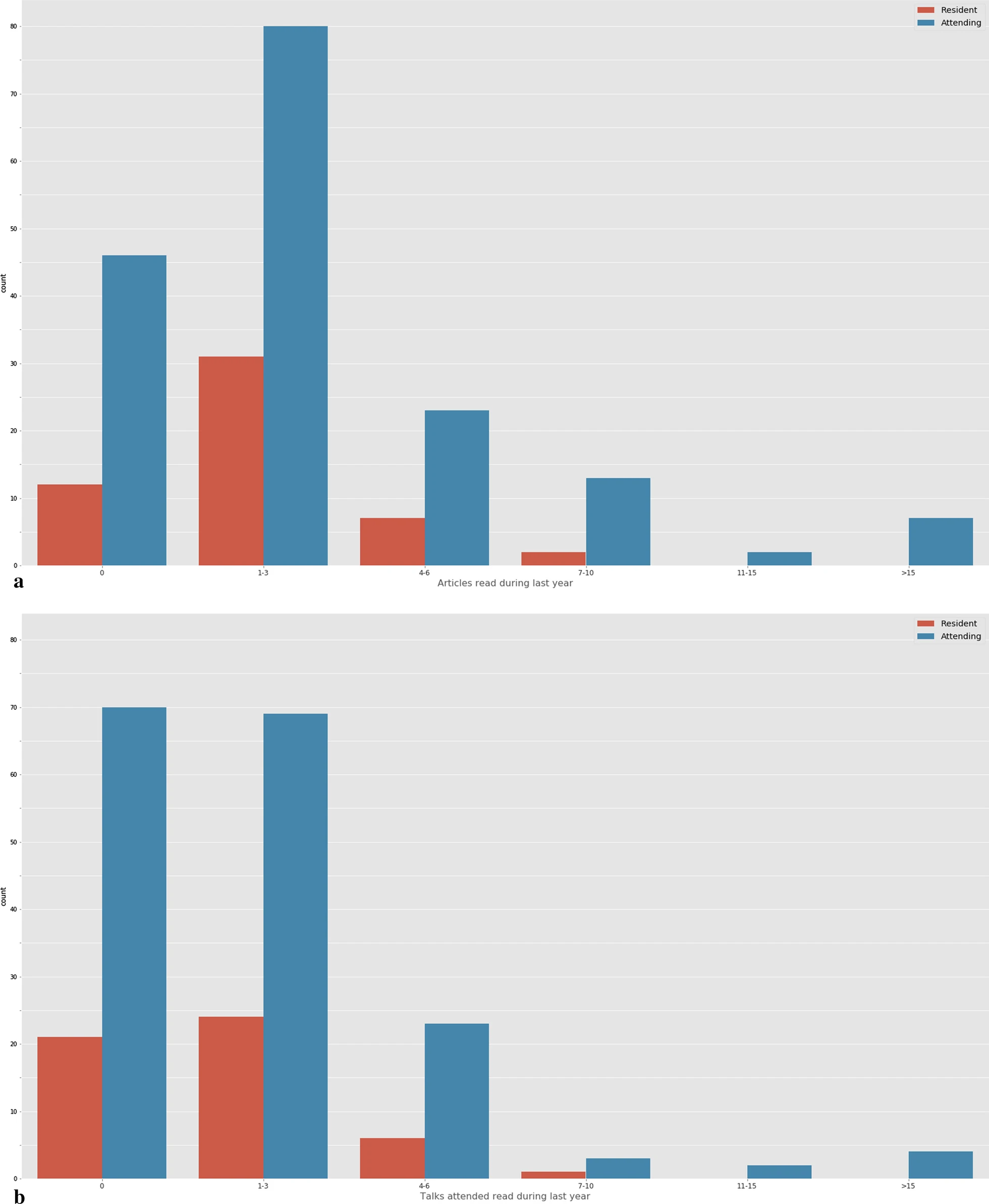

40.8% of the respondents had not attended to any communications or lectures on the topic during the previous year, while 41.7% had attended to less than three. Similarly, 49.8% of the radiologists had read between one and three scientific articles, and 26% had not read any scientific articles on the subject (Fig. 3).

|

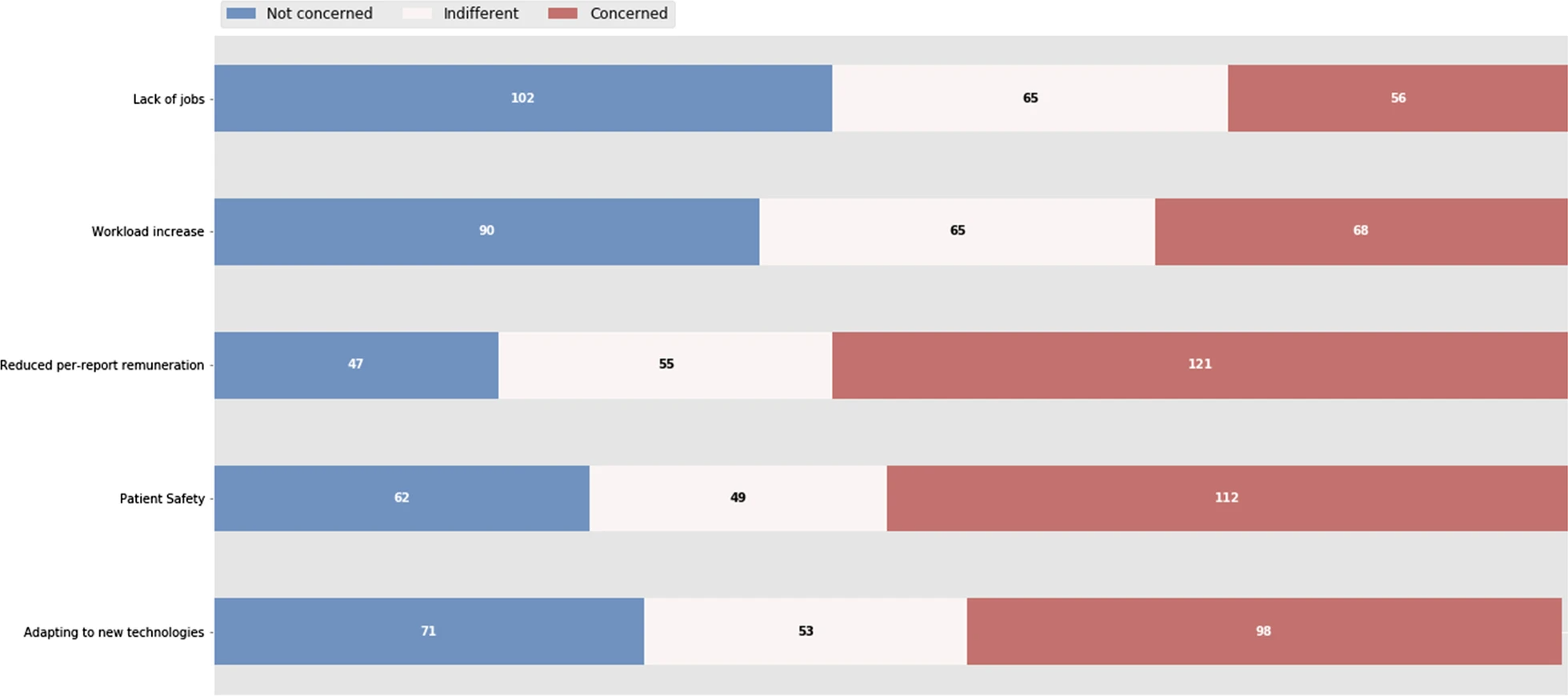

Patient safety (54.2%), adaptation to new technologies (50.2%), and a reduced per-report retribution (44.2%) were the main concerns. On the other hand, job loss was not seen as a peril by 45.7% of the participant. Regarding workload increase, 40.4% were not worried, while 30.5% manifested some concern (Fig. 4).

|

Discussion

We have assessed the general understanding and concerns on AI-related topics among radiologists working in Spain. Similar studies have been carried out in the past years in other European countries such as Italy[12], France[13], and Switzerland[14], and even among ESR members.[15] There have also been surveys in the United States[16], Singapore[17], and Saudi Arabia.[18] Perhaps one of the most comprehensive studies in this regard so far is the two-part international survey conducted by Huisman et al.[19][20] in 2019.

Our distribution of respondents showed a greater proportion of residents than expected based on the SERAM members distribution. This trend was also seen in a nationwide online Italian survey responded by 1,032 Società Italiana di Radiologia Medica e Interventistica members, in which the age distribution of responders was younger than expected.[12] There could be a great variety of factors to explain our results, such as a greater interest in AI among younger radiologists since it might have a greater impact in their future career, a belief also shared by the authors of the Italian survey.[12] Nevertheless, sample size or accessibility to the survey could have also played a part. For instance, the circulation of our survey was by convenience, generating an inherent bias based on whoever received the survey and their contacts.

When asked about AI and specific terms, the vast majority have either heard about AI or used it in daily work, while only two of the 223 respondents have not heard about AI. This result is consistent with other similar surveys.[16][17][18][19][20] Other generic terms such as "algorithm," "machine learning," and "convolutional neural network" were also familiar to the 50–75% of participants. This is to be expected, as in the recent years there has been an outburst of lectures and articles about AI. Some radiological societies such as ESR and Canadian Association of Radiology have redacted white papers on this topic[4][21], and others, such as EuSoMII[22], an institutional member society of the ESR, conduct training activities on AI.

However, when asked about more specific terms such as "backpropagation" or "blackbox," or about programming languages like Python or R, the results were reversed, with most of the participants having little clue about them. The significant differences found among groups for terms such as "artificial intelligence," "algorithm," "backpropagation," and "blackbox" could be explained by a higher exposure or use of commercial products by the attending physicians or by their involvement in research projects. Collado-Mesa et al.[16] found that only 33% of the respondents from a survey in a single center in the U.S. recognized speech recognition as an AI tool even though all of the participants used it on a daily basis. Our results are also in-line with the work of Huisman et al., in which only a minority of respondents (16%) had advanced AI skills.[19] This manifests that although radiologists are aware of AI, most of them only scratch the surface or are unaware that AI/ML is already implemented. If that alone is enough to survive in a future in which AI is fully operational in the daily workflow is yet to be seen. In fact, in our survey, 44.2% of the participants were concerned about adapting to the new technologies as opposed to the 32% that thought otherwise.

The aforementioned could be associated with the number of AI/ML-based lectures or papers read in the past year. Overall, 82.5% attended to three or fewer lectures (40.8% none) and 75.8% read three or fewer papers (26% none). A multicenter survey conducted in Singapore[17] showed similar results in which 29.6% of participants had not read a single paper in the previous six months and 56% had read between one and five. Similarly, 80.8% did not attend any data science course in the previous five years.[17] Collado-Mesa et al.[16] argued in 2017 that a possible explanation for the low exposure to AI/ML scientific literature could be the relatively few AI-based articles in main radiology journals, although we believe this is drastically changing, as the number of articles is growing exponentially. Another reason for this low exposure might be the lack of implementation of AI/ML programs in residency. For instance, there is no mention of imaging informatics in the Spanish official radiology residency curriculum other than a reference to office software and teleradiology tools, as well as the use of the internet as an information source.[23] As for the European training curriculum, the Level I and II document (March 2020) cites “to understand functioning and application of AI tools, knowledge of ethics of AI and performance assessment and critical appraisal.”[24]

Every participant manifested the need to pursue academic training in new technologies, and 92.9% thought this should be implemented in the specialty’s academic program. This has been also stated in other similar surveys.[15][16][17][20]

In this regard, Lindqwister et al.[25] conducted a recent pilot model for an integrated AI curriculum (AI-RADS) in radiology at Dartmouth College in the U.S. The course was based on a sequence of foundational algorithms in AI presented as logical extensions of each other in lessons of one hour (once per month for a total of seven months) and reinforced with a concurrent journal club highlighting the algorithm discussed in the previous lecture. The course was also paired with secondary lessons in key topics such as pixel mathematics since most of the participants did not have a computational background. The course received a 9.8/10 satisfaction rating, and through the course residents perceived a better understanding of basic concepts in AI.[25]

Wiggings et al.[26] designed and implemented a focused data science pathway for senior radiology residents. In this model, three fourth-year residents with varying technical background were involved in a data science pathway aimed to address all stages of clinical ML model development (fundamentals, data curation, model development, and clinical integration) with proper mentorship. The authors noted that fundamentals in mathematics, basic coding, ML theory, data curation, and model development, as well as clinical integration, are key factors for a successful engagement in clinical data science. The experience gained in this pilot project would help improve the training experience in consecutive years for a long-term success of this curriculum. At the end of the training, participants showed a desire for a more formal didactic curriculum.[26]

A pilot project for residents including skills such as data management, general ML, and DL using Python is being conducted at our institution, with emphasis on evaluation and critical assessment. After this pilot experience is completed and evaluated, we plan to implement a formal program for all the second-year (basic knowledge and theoretical approach) and third- and fourth-year residents (hands-on project-based approach), with guidance and mentorship from the first cohort of residents.

There was a consensus among our respondents that adding an AI curriculum into the four-year residency program might not be enough for a good foundation in AI. These results are difficult to interpret since the required level or knowledge of that training was not included in the questionnaire, and neither was asked whether participants were aware of the European training curriculum previously mentioned. To the best of our knowledge, there is no consensus in Europe about what this teaching itinerary should be. Regardless, we believe the current model needs to change if we want to produce radiologists with the sufficient AI skills during the radiology residency or beyond. Trainees might not need to spend that much time mastering pattern recognition and could spend more time learning data science and AI.[27]

The general lack of concern about job loss shown in our results is also shared in almost every other survey[12][14][15][17][18][19][20], in which radiologists are rather keen to incorporate it in daily work. In the Italian survey, about 66% of the respondents defined AI as an aid to daily practice and believed that image interpretation will eventually be handled by AI.[12] There is also a consensus that AI will help reduce errors and optimize radiologists’ work[12][13] as well as the administrative burden.[16] This is in agreement with the results from the international survey carried on by Huisman et al., in which the responders believe AI will change radiologists tasks rather than fully replace them.[19] The most extensive series show a concern for the change in the radiologist's tasks (82%) much more than a total replacement of radiologists (10%).[19] Recent advances, then, lead us to consider that AI will change radiology as we currently know it. But perhaps the transformation will not be as disruptive as initially imagined, but more organic and intertwined with the daily workflow, granting us the ability to achieve a synergy between radiologist and computer, and allowing radiologists to spend their time performing value-added functions and increase their professional satisfaction. This view is supported by some of the existing literature, where as many as 77% of respondents believe that workflow optimization will be possible by these tools.[20] In this regard, AI should be viewed as a wingman instead of a direct competitor, and we should not be afraid of incorporating AI, viewing it as an opportunity to be in the vanguard as it might also have an impact in another medical fields. In fact, there is a growing belief that it could empower radiologists creating a new profile focused on data analysis: radiologists as clinical data scientists.[28] There is indeed a need to reshape the current radiologist role to avoid being overtaken by clinicians or by other experts in AI, and even lead AI projects involving radiological images. Some of the free answers given by the respondents are in concordance with this statement, such as: “We need to work with engineers and IT. We are the analysts, and they are the developers.” This goes against some of the most pessimistic opinions, which also do not consider some tasks that cannot be yet performed by AI such as interventionism, both vascular and non-vascular, or participation in multidisciplinary meetings.

Opinions about the workload increase were quite similar, as 30.5% were concerned about a possible increase, while 40.4% were not worried at all. In the EuroAIM survey, almost 75% of the respondents felt that AI will impact workload, but it was unclear whether it might be an increase or not[15], and in the Italian survey there was a minority who thought that AI would increase workload.[12] Both articles concluded that these differences reflect the doubt on the impact of AI in radiology, a statement we share based on our own results.

The EuroAIM survey showed that 55% of responders believe that patients will not accept a report made by an AI-application alone[15], results that are in-line with other publications.[3] Participants in the Swiss survey did not agree on where liability should lie in the event of an AI error.[14] A similar feeling is shared by the most pessimistic articles regarding the future of AI, in which the “human barrier” might be an obstacle for the full replacement of radiologists.[29] In our study, 50.2% of the participants were concerned about patient safety presumably due to the ethical–legal implications. Certainly, there is still debate on how errors, discrepancies, and malpractice when using these tools will be managed, which may result in reluctance toward its adoption not only by radiologists but also by patients and practitioners in other medical fields.[29][30] Ongena et al.[31] performed a questionnaire to 21 patients in the Netherlands and revealed that they were not optimistic about AI systems taking over diagnostic interpretations performed by radiologists. This highlights the importance of a strict regularization of AI tools in the field of radiology and the pivotal role of the patient in this process.

Finally, the opinion of students is also important as they are the future radiologists. Gong et al.[32] conducted a survey on 322 medical students in Canada revealed that 67.7% of them considered that AI would reduce the demand for radiologists and discouraged them from applying to the radiology specialty. However, prior AI background was associated with a more positive attitude. The Swiss survey also concurred that students might be afraid to specialize in radiology because of the peril of AI being a detrimental factor to their work security.[14] Due to the positive effect of previous AI knowledge in dissipating the fear of AI, we agree with both authors that AI curriculum should be included not only in radiology residency but also as part of earning a bachelor’s degree in medicine.

We consider the main limitation of our study to be selection bias stemming from both initial survey disclosure and convenience sampling secondary to subsequent sharing by respondents to colleagues and acquaintances. Also, a greater participation would improve the robustness of our results and allow us to draw better conclusions. In retrospect, we found certain methodological flaws on the design of certain questions and options provided, which we consider could be improved in order to better assess the responses. Specifically, the precise reasons about patient safety and ethical–legal implications were not asked, and therefore the interpretation of these results may be somewhat ambiguous.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a general lack of knowledge about AI, ML, and related topics among Spanish radiologists, including both members in training and attending physicians. Nevertheless, there is widespread enthusiasm to delve deeper into this matter, as also seen in surveys carried out in other countries. Job loss was not a major concern among those surveyed, against the most ominous voices that predict the extinction of our discipline. While there are a few institutional initiatives—including ours—that aim to train their radiologists in this domain, there is no doubt that a common consensus is needed to change the current training curriculum to prepare new radiologists for a future world in which AI will undoubtedly shape the profession.

Abbreviations

AI: artificial intelligence

AP: attending physician

CAD: computer-aided design

DL: deep learning

ESR: European Society of Radiology

ML: machine learning

RSNA: Radiological Society of North America

SERAM: Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica

Acknowledgements

We thank Javier Chacón Álvarez for his assistance in the grammatical revision and proofreading of this manuscript.

Author contributions

DE and MF conceived and designed the study. DE acquired the data. DE and AA analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and have contributed equally to the work. MF, VP, ME and NR carried out the critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- ↑ Freer, Timothy W.; Ulissey, Michael J. (1 September 2001). "Screening Mammography with Computer-aided Detection: Prospective Study of 12,860 Patients in a Community Breast Center" (in en). Radiology 220 (3): 781–786. doi:10.1148/radiol.2203001282. ISSN 0033-8419. http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/radiol.2203001282.

- ↑ Yuan, Ren; Vos, Patrick M.; Cooperberg, Peter L. (1 May 2006). "Computer-Aided Detection in Screening CT for Pulmonary Nodules" (in en). American Journal of Roentgenology 186 (5): 1280–1287. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1969. ISSN 0361-803X. http://www.ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.04.1969.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Litjens, Geert; Kooi, Thijs; Bejnordi, Babak Ehteshami; Setio, Arnaud Arindra Adiyoso; Ciompi, Francesco; Ghafoorian, Mohsen; van der Laak, Jeroen A.W.M.; van Ginneken, Bram et al. (1 December 2017). "A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis" (in en). Medical Image Analysis 42: 60–88. doi:10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1361841517301135.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 European Society of Radiology (ESR) (1 December 2019). "What the radiologist should know about artificial intelligence – an ESR white paper" (in en). Insights into Imaging 10 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/s13244-019-0738-2. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC PMC6449411. PMID 30949865. https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13244-019-0738-2.

- ↑ "AI Blog". European Society of Radiology. https://ai.myesr.org/. Retrieved 04 November 2020.

- ↑ "AI resources and training". Radiological Society of North America. https://www.rsna.org/education/ai-resources-and-training. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ "Radiology: Artificial Intelligence". Radiological Society of North America. https://pubs.rsna.org/journal/ai. Retrieved 05 November 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Langlotz, Curtis P.; Allen, Bibb; Erickson, Bradley J.; Kalpathy-Cramer, Jayashree; Bigelow, Keith; Cook, Tessa S.; Flanders, Adam E.; Lungren, Matthew P. et al. (1 June 2019). "A Roadmap for Foundational Research on Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging: From the 2018 NIH/RSNA/ACR/The Academy Workshop" (in en). Radiology 291 (3): 781–791. doi:10.1148/radiol.2019190613. ISSN 0033-8419. PMC PMC6542624. PMID 30990384. http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/radiol.2019190613.

- ↑ European Society of Radiology (ESR) (1 October 2017). "ESR concept paper on value-based radiology" (in en). Insights into Imaging 8 (5): 447–454. doi:10.1007/s13244-017-0566-1. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC PMC5621991. PMID 28856600. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s13244-017-0566-1.

- ↑ Chartrand, Gabriel; Cheng, Phillip M.; Vorontsov, Eugene; Drozdzal, Michal; Turcotte, Simon; Pal, Christopher J.; Kadoury, Samuel; Tang, An (1 November 2017). "Deep Learning: A Primer for Radiologists" (in en). RadioGraphics 37 (7): 2113–2131. doi:10.1148/rg.2017170077. ISSN 0271-5333. http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/rg.2017170077.

- ↑ Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (2020). "Memoria SERAM 2018-2020" (PDF). Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica. https://seram.es/images/site/memorias/memoria_seram_2020_v2.pdf. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Coppola, Francesca; Faggioni, Lorenzo; Regge, Daniele; Giovagnoni, Andrea; Golfieri, Rita; Bibbolino, Corrado; Miele, Vittorio; Neri, Emanuele et al. (1 January 2021). "Artificial intelligence: radiologists’ expectations and opinions gleaned from a nationwide online survey" (in en). La radiologia medica 126 (1): 63–71. doi:10.1007/s11547-020-01205-y. ISSN 0033-8362. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11547-020-01205-y.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Waymel, Q.; Badr, S.; Demondion, X.; Cotten, A.; Jacques, T. (1 June 2019). "Impact of the rise of artificial intelligence in radiology: What do radiologists think?" (in en). Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 100 (6): 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.diii.2019.03.015. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211568419300907.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 van Hoek, Jasper; Huber, Adrian; Leichtle, Alexander; Härmä, Kirsi; Hilt, Daniella; von Tengg-Kobligk, Hendrik; Heverhagen, Johannes; Poellinger, Alexander (1 December 2019). "A survey on the future of radiology among radiologists, medical students and surgeons: Students and surgeons tend to be more skeptical about artificial intelligence and radiologists may fear that other disciplines take over" (in en). European Journal of Radiology 121: 108742. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108742. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0720048X19303924.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 European Society of Radiology (ESR) (1 December 2019). "Impact of artificial intelligence on radiology: a EuroAIM survey among members of the European Society of Radiology" (in en). Insights into Imaging 10 (1): 105. doi:10.1186/s13244-019-0798-3. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC PMC6823335. PMID 31673823. https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13244-019-0798-3.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Collado-Mesa, Fernando; Alvarez, Edilberto; Arheart, Kris (1 December 2018). "The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Radiology: A Survey at a Single Radiology Residency Training Program" (in en). Journal of the American College of Radiology 15 (12): 1753–1757. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2017.12.021. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1546144017316666.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Ooi, Skg; Makmur, A; Soon, Yqa; Fook-Chong, Smc; Liew, Cj; Sia, Dsy; Ting, Y; Lim, Cy (1 March 2021). "Attitudes toward artificial intelligence in radiology with learner needs assessment within radiology residency programmes: a national multi-programme survey". Singapore Medical Journal 62 (3): 126–134. doi:10.11622/smedj.2019141. PMC PMC8027147. PMID 31680181. http://www.smj.org.sg/article/attitudes-toward-artificial-intelligence-radiology-learner-needs-assessment-within-radiology.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Tajaldeen, Abdulrahman; Alghamdi, Salem (1 July 2020). "Evaluation of radiologist’s knowledge about the Artificial Intelligence in diagnostic radiology: a survey-based study" (in en). Acta Radiologica Open 9 (7): 205846012094532. doi:10.1177/2058460120945320. ISSN 2058-4601. PMC PMC7412626. PMID 32821436. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2058460120945320.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 Huisman, Merel; Ranschaert, Erik; Parker, William; Mastrodicasa, Domenico; Koci, Martin; Pinto de Santos, Daniel; Coppola, Francesca; Morozov, Sergey et al. (1 September 2021). "An international survey on AI in radiology in 1,041 radiologists and radiology residents part 1: fear of replacement, knowledge, and attitude" (in en). European Radiology 31 (9): 7058–7066. doi:10.1007/s00330-021-07781-5. ISSN 0938-7994. PMC PMC8379099. PMID 33744991. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00330-021-07781-5.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Huisman, Merel; Ranschaert, Erik; Parker, William; Mastrodicasa, Domenico; Koci, Martin; Pinto de Santos, Daniel; Coppola, Francesca; Morozov, Sergey et al. (1 November 2021). "An international survey on AI in radiology in 1041 radiologists and radiology residents part 2: expectations, hurdles to implementation, and education" (in en). European Radiology 31 (11): 8797–8806. doi:10.1007/s00330-021-07782-4. ISSN 0938-7994. PMC PMC8111651. PMID 33974148. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00330-021-07782-4.

- ↑ Tang, An; Tam, Roger; Cadrin-Chênevert, Alexandre; Guest, Will; Chong, Jaron; Barfett, Joseph; Chepelev, Leonid; Cairns, Robyn et al. (1 May 2018). "Canadian Association of Radiologists White Paper on Artificial Intelligence in Radiology" (in en). Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal 69 (2): 120–135. doi:10.1016/j.carj.2018.02.002. ISSN 0846-5371. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1016/j.carj.2018.02.002.

- ↑ "European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics (EuSoMII)". European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics. https://www.eusomii.org/. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ↑ Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (10 March 2008). "ORDEN SCO/634/2008, de 15 de febrero, por la que se aprueba y publica el programa formativo de la especialidad de Radiodiagnóstico." (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado. https://boe.es/boe/dias/2008/03/10/pdfs/A14333-14341.pdf. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ↑ "ESR European Training Curriculum Level I-II". European Society of Radiology. 2020. https://www.myesr.org/media/2838. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Lindqwister, Alexander L.; Hassanpour, Saeed; Lewis, Petra J.; Sin, Jessica M. (1 December 2021). "AI-RADS: An Artificial Intelligence Curriculum for Residents" (in English). Academic Radiology 28 (12): 1810–1816. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2020.09.017. ISSN 1076-6332. PMC PMC7563580. PMID 33071185. https://www.academicradiology.org/article/S1076-6332(20)30556-0/abstract.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Wiggins, Walter F.; Caton, M. Travis; Magudia, Kirti; Glomski, Sha-har A.; George, Elizabeth; Rosenthal, Michael H.; Gaviola, Glenn C.; Andriole, Katherine P. (1 November 2020). "Preparing Radiologists to Lead in the Era of Artificial Intelligence: Designing and Implementing a Focused Data Science Pathway for Senior Radiology Residents" (in en). Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2 (6): e200057. doi:10.1148/ryai.2020200057. ISSN 2638-6100. PMC PMC8082300. PMID 33937848. http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/ryai.2020200057.

- ↑ Jha, Saurabh; Topol, Eric J. (13 December 2016). "Adapting to Artificial Intelligence: Radiologists and Pathologists as Information Specialists" (in en). JAMA 316 (22): 2353. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17438. ISSN 0098-7484. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2016.17438.

- ↑ Tas, J. (2015). "Today’s radiologist, tomorrow’s data scientist". Philips. https://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/articles/2022/20220303-philips-and-the-philips-foundation-provide-support-for-the-people-of-ukraine.html. Retrieved November 2021.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Chockley, Katie; Emanuel, Ezekiel (1 December 2016). "The End of Radiology? Three Threats to the Future Practice of Radiology" (in en). Journal of the American College of Radiology 13 (12): 1415–1420. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2016.07.010. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1546144016305907.

- ↑ Wong, S. H.; Al-Hasani, H.; Alam, Z.; Alam, A. (1 January 2019). "Artificial intelligence in radiology: how will we be affected?" (in en). European Radiology 29 (1): 141–143. doi:10.1007/s00330-018-5644-3. ISSN 0938-7994. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00330-018-5644-3.

- ↑ Ongena, Yfke P.; Haan, Marieke; Yakar, Derya; Kwee, Thomas C. (1 February 2020). "Patients’ views on the implementation of artificial intelligence in radiology: development and validation of a standardized questionnaire" (in en). European Radiology 30 (2): 1033–1040. doi:10.1007/s00330-019-06486-0. ISSN 0938-7994. PMC PMC6957541. PMID 31705254. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00330-019-06486-0.

- ↑ Gong, Bo; Nugent, James P.; Guest, William; Parker, William; Chang, Paul J.; Khosa, Faisal; Nicolaou, Savvas (1 April 2019). "Influence of Artificial Intelligence on Canadian Medical Students' Preference for Radiology Specialty: ANational Survey Study" (in en). Academic Radiology 26 (4): 566–577. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2018.10.007. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1076633218304719.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, spelling, and grammar. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.